On this day on 14th October

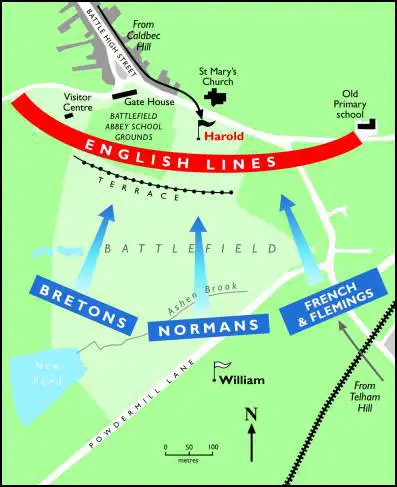

On this day in 1066 the Battle of Hastings took place. Harold of Wessex realised he was unable to take William of Normandy by surprise. He therefore decided to position himself at Senlac Hill near Hastings. Harold selected a spot that was protected on each flank by marshy land. At his rear was a forest. The English housecarls provided a shield wall at the front of Harold's army. They carried large battle-axes and were considered to be the toughest fighters in Europe. The fyrd were placed behind the housecarls. The leaders of the fyrd, the thanes, had swords and javelins but the rest of the men were inexperienced fighters and carried weapons such as iron-studded clubs, scythes, reaping hooks and hay forks.

There are no accurate figures of the number of soldiers who took part at the Battle of Hastings. Historians have estimated that William had about 5,000 infantry and 3,000 knights while Harold had about 2,000 housecarls and 5,000 members of the fyrd. The Norman historian, William of Poitiers, claims that Harold held the advantage: "The English were greatly helped by the advantage of the high ground... also by their great number, and further, by their weapons which could easily find a way through shields and other defences."

The Norman army led by William now marched forward in three main groups. On the left were the Breton auxiliaries. On the right were a more miscellaneous body that included men from Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders. In the centre was the main Norman contingent "with Duke William himself, relics round his neck, and the papal banner above his head".

On this day in 1322 Robert the Bruce of Scotland defeats King Edward II of England at Bannockburn, forcing Edward to accept Scotland's independence. The barons also became angry about Edward's poor military leadership. Supported by his new favourite, Hugh de Despenser, Edward arrested Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, the leader of the barons, and had him executed. Edward's wife, Isabella of France, was also very critical of the way her husband was ruling the country. In 1322 she left Edward and went to live with her lover, Roger Mortimer, in France. In 1326 Isabella and Mortimer returned to England and with the support of the barons, forced Edward II to abdicate. Edward was imprisoned and Hugh de Despenser was executed. The following year Mortimer arranged for Edward to to be murdered in Berkeley Castle.

On this day in 1893 May Wedderburn Cannan was born in Oxford. Her father, Charles Cannan, was Dean of Trinity College. May took a keen interest in literature and had her first poem published in The Scotsman in 1908.

When she was 18 she joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment. May trained as a nurse and eventually reached the rank of Quartermaster. In 1913 she was instructed by the Home Office to make plans to set up a small hospital of 60 beds if mobilized. However, on the outbreak of the First World War, May had to hand over responsibility to a senior officer and she worked as an auxiliary nurse.

May Wedderburn spent four weeks at Rouen in France, before returning to England where she helped her father run the Clarendon Press. This included publishing material produced by the government's War Propaganda Bureau. She also worked for a short period in Paris for MI5. In 1917 May published a book of poems about the war, In War Time.

During the war Cannan was engaged to marry the soldier Bevil Quiller-Couch. He survived the fighting at Mons and Ypres, but died at the end of the war of influenza.

May Wedderburn published her third volume of poetry, The House of Hope, in 1923. This inspired a letter from an admirer, Percival James Slater, had been wounded while serving in the Royal Flying Corps. According to Jane Potter: "Although they had met only five times the couple were married on 26 July 1924 at the parish church of St George, Camden Hill, London. They had one son, James Cannan Slater."

Her first volume of memoirs, The Lonely Generation, was published in 1934. The second volume, Grey Ghosts and Voices (1976) did not appear until after her death.

May Wedderburn Cannan suffered a heart attack and died in her sleep at her home in Pangbourne, Berkshire, on 11 December 1973.

On this day in 1892 Arthur Conan Doyle publishes The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Conan Doyle set up as a doctor in Southsea, a suburb of Portsmouth. With very few patients, Conan Doyle attempted to make money by writing detective stories. His main character, Sherlock Holmes, was based on Dr. Joseph Bell, a surgeon and criminal psychologist, who lectured at Edinburgh Infirmary. In 1891 Conan Doyle published six Sherlock Holmes stories in the Strand Magazine. The following year he was paid £1,000 for a whole series on Sherlock Holmes. Conan Doyle really wanted to write historical novels like his hero, Sir Walter Scott, and in 1893 decided to kill off Sherlock Holmes in the story, The Final Problem. However, after coming under considerable pressure from his fans, he returned to write his best known detective story, The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1902.

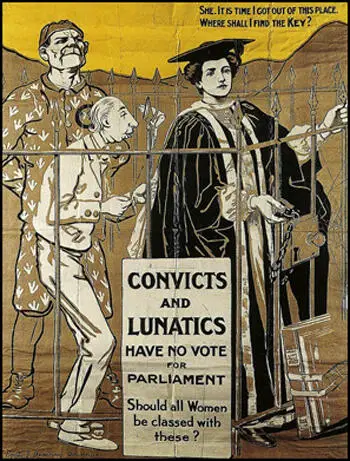

On this day in 1897 the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies is formed. By the 1890s there were seventeen individual groups that were advocating women's suffrage. This included the London Society for Women's Suffrage, Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage, Liberal Women's Suffrage Society and the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage. On 14th October 1897, these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Millicent Garrett Fawcett was elected as president. Other members of the executive committee included Marie Corbett, Chrystal Macmillan, Maude Royden and Eleanor Rathbone.

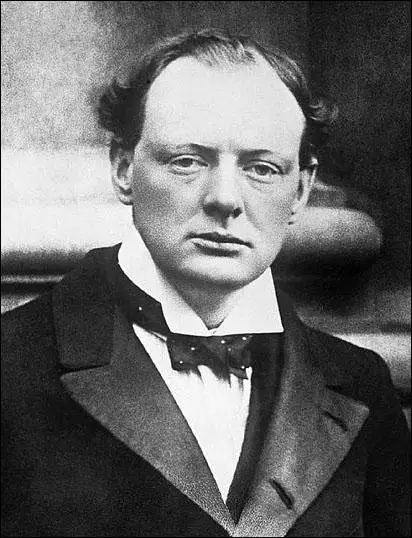

On this day in 1899 The Morning Post reporter Winston Churchill departed to South Africa to cover the Boer War. Churchill had negotiated a contract with the newspaper which made him the highest-paid war correspondent of the day, with a salary of £250 per month with all his expenses paid. A fellow journalist, John Black Atkins, who worked for the Manchester Guardian, commented: "He (Churchill) was slim, slightly reddish-haired, pale, lively.. when the prospects of a career like that of his father, Lord Randolph, excited him, then such a gleam shone from him that he was almost transfigured. I had not before encountered this sort of ambition, unabashed, frankly egotistical, communicating its excitement, and extorting sympathy."

On this day in 1906 Hannah Arendt, the daughter of Paul and Martha Arendt, was born in Hanover. Her father was a successful businessman but held progressive political opinions. Paul and Martha were both members of the German Social Democratic Party. Paul had been suffering from syphilis for many years and died in a psychiatric hospital in 1913 when Hannah was only seven. It has been claimed by Derwent May that "those who knew her well could see that Hannah kept a deep sorrow buried inside her."

Hannah's mother had no religious faith but she brought her daughter up to be proud of her Jewish heritage. She had little interest in tradition or ritual. Hannah felt that her dark brown eyes made her look a little different than other children. There was the odd anti-Semitic comment but anti-Semitism was not a serious problem in those years.

Hannah's mother made it clear how she respond to anti-Semitism: "When my teachers made anti-Semitic remarks - mostly not about me, but about other Jewish girls, eastern Jewish students in particular - I was told to get up immediately, leave the classroom, come home, and report everything exactly. Then my mother wrote one of her many registered letters; and for me the matter was completely settled. I had a day off from school, and that was marvelous! But when it came from children, I was not permitted to tell about it at home. That defended yourself against what came from children."

In 1920, when she was thirteen, her mother married again. Her new husband, Martin Beerwald, a successful Jewish businessman, had two teenage daughters (his first wife had died a few years before), Clara, who was now twenty, and Eva who was nineteen. They were all supporters of the Social Democratic Party and Hannah enjoyed the political discussions that took place in the family.

Hannah Arendt was an extremely intelligent teenager and became interested in Greek philosophy. "Headstrong and independent, she displayed a precocious aptitude for the life of the mind. And while she might risk confrontation with a teacher who offended her with an inconsiderate remark - she was briefly expelled for leading a boycott of the teacher's classes."

Hannah's fellow students found her a very attractive young woman. Hannah was described as having "striking looks: thick, dark hair, a long, oval face, and brilliant eyes". One student claimed that she had "lonely eyes" but "starry when she was happy and excited". Another friend described them as "deep, dark, remote pools of inwardness."

Arendt later recalled that life was difficult as a Jew living in Germany: "One thing was certain: if one wanted to avoid all ambiguities of social existence, one had to resign oneself to the fact that to be a Jew meant to belong either to an over privileged upper class or to an underprivileged mass which, in Western and Central Europe, one could belong to only through an intellectual and somewhat artificial solidarity."

At the age of sixteen, Martha Arendt, arranged for her to spend two terms studying in Berlin, where the family had friends. Hannah lived in a student residence and took classes in Latin and Greek at the university, where she was introduced to theology by Romano Guardini, a Christian existentialist, who introduced her to the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Jaspers.

At the age of sixteen, Martha Arendt, arranged for her to spend two terms studying in Berlin, where the family had friends. Hannah lived in a student residence and took classes in Latin and Greek at the university, where she was introduced to theology by Romano Guardini, a Christian existentialist, who introduced her to the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Jaspers.

In 1924 Hannah Arendt went to University of Marburg where she studied philosophy under Martin Heidegger. He was thirty-five years old and married to Elfride Heidegger when they met: "He was an exceptionally brilliant man but, in his professional and private life, a cautious one... He was also, it would seem, rather vain and self-conscious: he was short, and always insisted on sitting down when he was photographed, so that this would be less apparent."

On this day in 1918 General Nikolai Yudenich captured Gatchina, only 50 kilometres from Petrograd. It is estimated that there were 200,000 foreign soldiers supporting the anti-Bolshevik forces. Trotsky arrived to direct the defence of the capital. He was not very impressed and it is claimed that his first action was to order Ivan Pavlunovsky, chief of the special section of the Petrograd Cheka, "Comrade Pavlunovsky, I command you to arrest immediately and shoot the entire staff for the defence of Petrograd."

Trotsky made it clear to the people of Petrograd that the city would not be surrendered: "As soon as the masses began to feel that Petrograd was not to be surrendered, and if necessary would be defended from within, in the streets and squares, the spirit changed at once. The more courageous and self-sacrificing lifted up their heads. Detachments of men and women, with trenching-tools on their shoulders, filed out of the mills and factories.... The whole city was divided into sections, controlled by staffs of workers. The more important points were surrounded by barbed wire. A number of positions were chosen for artillery, with a firing range marked off in advance. About sixty guns were placed behind cover on the open squares and at the more important street-crossings. Canals, gardens; walls, fences and houses were fortified. Trenches were dug in the suburbs and along the Neva. The whole southern part of the city was transformed into a fortress. Barricades were raised on many of the streets and squares."

with the dogs, Anton Denikin, Alexander Kolchak and Nikolai Yudenich on leash (1918)

On this day in 1926 A. A. Milne's book Winnie-the-Pooh was published. It was a great success and it was followed by The House at Pooh Corner in 1928. These stories took place in Posingford Wood close to Milne's home. Milne contined to write plays and novels but they failed to make him any money, unlike his children stories. Claire Tomalin has pointed out that "his fame as a children's writer made it increasingly difficult for him to interest public, critics or publishers in the other, more serious work."

On this day in 1940 Balham tube station in London is bombed by the Luftwaffe during the Blitz. A 1400 kg fragmentation bomb fell on the road above the northern end of the platform tunnels, creating a large crater into which a double decker bus then crashed. The northbound platform tunnel partially collapsed and was filled with earth and water from the fractured water mains and sewers above. Although more than 400 managed to escape, 68 people died in the disaster, including the stationmaster, the ticket-office clerk and two porters. Many drowned as water and sewage from burst mains poured in, soon reaching a depth of three feet.

On this day in 1943 600 Jewish prisoners mount an uprising at the Nazi extermination camp in Sobibor, Poland. The commandant was Franz Stangl and according to one source 90,000-100,000 Jews were murdered at Sobibor in the camp's first 90 days alone. The uprising was led by Alexander Pechersky, a captured member of the Red Army. About 320 Jews managed to make it outside of the camp in the ensuing melee. Eighty were killed in the escape and immediate aftermath. 170 were soon recaptured and killed, as were all the remaining inhabitants of the camp who had chosen to stay. Some escapees joined the partisans. Of these, ninety died in combat. Only nine of those who escaped, including Pechersky, survived the war.

On this day in 1949 14 leaders of the American Communist Party were convicted of sedition and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This included Eugene Dennis, the general secretary, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government". They were sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years. They appealed to the Supreme Court but on 4th June, 1951, the judges ruled, 6-2, that the conviction was legal.

Williamson and Jacob Stachel leaving the courthouseduring their trial (21st July, 1948)

On this day in 1950 Barbara Ayrton Gould died.

Barbara Ayrton, the daughter of William Ayrton and Hertha Ayrton, was born in 1886. Her half-sister was Edith Zangwill. She was educated at Notting Hill High School and University College, where she studied chemistry and physiology.

In 1906 Barbara Ayrton joined the Women Social & Political Union. In 1908 she gave up her post-graduate research in order to work full-time as an organizer for the WSPU. In November 1909 she played the part of Grace Darling in A Pageant of Great Women at the Scala Theatre, a play by Cicely Hamilton.

In July 1910, Barbara Ayrton, married Gerald Gould. A fellow socialist, Gould was a Fellow of Merton College at the University of Oxford. He was also a supporter of women's suffrage and had joined forces with Henry Nevinson, Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin and Charles Mansell-Moullin to establish the Men's League For Women's Suffrage.

On 4th March, 1912 the WSPU organised another window-breaking demonstration. This time the target was government offices in Whitehall. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent." Over 200 suffragettes were arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration. This included Barbara Gould was arrested for breaking windows in Regent Street. She was remanded in Holloway Prison but was released without charge.

In October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

Barbara Ayrton Gould also disagreed with the arson campaign and left the WSPU. On 6th February, 1914, she became one of the founding members of the United Suffragists. Other members included Gerald Gould, Evelyn Sharp, Lena Ashwell, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, John Scurr, George Lansbury, Gerald Gould, Hertha Ayrton, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Edith Zangwill, Israel Zangwill, Laurence Housman and Henry Nevinson. She was also a member of the Tax Resistance League.

In 1921 Barbara gave birth to Michael Ayrton. She was honorary secretary of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. She also remained active in the Labour Party and was a member of the national executive for over 20 years. She was also vice-chairman from 1938 to 1939 and chairman from 1939 to 1940. At the fifth attempt, she was elected to represent North Hendon in the 1945 General Election.

Barbara Ayrton Gould died on 14th October 1950.

On this day in 1957 Helena Normanton died and was buried at St Wulfran's Churchyard in Ovingdean.

Helena Normanton, the daughter of William Normanton, a pianoforte manufacturer, was born in London on 14th December 1882. When Helena was aged four, her father, aged 33, was found dead with a broken neck in a railway tunnel. Her mother, Jane Normanton, moved to Brighton with her two young daughters. She ran a small grocery shop and also turned her family home at 4 Clifton Place into a boarding house.

Normanton was a talented student and in 1896 won a scholarship to York Place Science School (later renamed Margaret Hardy School, forerunner of Varndean School for Girls). She eventually became a pupil teacher but on the death of her mother in 1900 she left school to help run the family boarding house and look after her younger sister. The following year she moved to 11 Hampton Place, Hove, a boarding house owned by her aunt, Eliza Whitehead.

In 1903 Helena became a student at the Edge Hill Teachers' Training College in Liverpool. After qualifying in 1905 she taught history in Glasgow and London. Helena was for a time the private tutor to the sons of Baron Maurice de Forest, the Liberal Party MP for West Ham North. Normanton was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Members of the WSPU began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Normanton, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

Like the WSPU, the Women's Freedom League was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL were especially critical of the WSPU arson campaign.

Normanton, like most members of the Women's Freedom League, was a pacifist, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 the organisation refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL such as Charlotte Despard believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Council for a negotiated peace.

As well as campaigning for women's suffrage, Normanton wrote several pamphlets on the issue of women's pay. In Sex Differentiation in Salary (1914) she argued for equal pay for equal work. After the First World War she wrote: "During and after the war, many soldiers' wives and widows became the breadwinners for families. Should they be paid according to their sex or their work?"

In 1918 Normanton applied to be admitted to the Middle Temple. When this application was rejected because she was a woman, she took the case to the House of Lords. However, before the case could be heard, Parliament passed the Disqualification (Removal) Bill. Normanton immediately applied again and therefore became the first woman admitted as a student to the bar. After passing her exams she was called to the bar on 17th November 1922, a few months after Ivy Williams, had become the first woman to do so (but she did not practise).

While a student Normanton married Gavin Bowman Clark (1873-1948). As Joanne Workman has pointed out: "Her application to retain her maiden name after her marriage attracted considerable public interest. Helena deplored the loss of a woman's identity on marriage and its disadvantageous legal results. While she believed in the respectability of retaining the title Mrs she also wished to maintain continuity of identity in her professional career." In 1924 she became the first married British woman to be issued a passport in her maiden name.

Normanton gained a great deal of fame "from her writing, public speaking, and feminist activities". This led to claims that she was guilty of advertising her services (forbidden by legal etiquette). In April 1923 she requested the bar council to hold a full inquiry into whether she had ever advertised herself. As this did not happen she curtailed her public speaking engagements and stopped writing for newspapers and magazines.

In 1924 Helena Normanton became the first female counsel in a case at the Old Bailey. The following year she became the first woman to conduct a case in the United States, that established American women's right to retain their maiden names. Despite these achievements her earning from legal work was so low she had to supplement her income by renting rooms in her house in Mecklenburgh Square, Bloomsbury. She also published two books on famous criminal cases, The Trial of Norman Thorne (1929) and The Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse (1931).

Helena Normanton campaigned for changes in matrimonial law. At the annual meeting of the National Council of Women in October 1934, her proposals were strongly attacked by the Mothers' Union. In 1938 Normanton was co-founder with Vera Brittain, Edith Summerskill and Helen Nutting of the Married Women's Association. The organisation sought equal relationships between men and women in marriage.

Helena Wojtczak remarked in Notable Sussex Women (2008): "In 1948 she became the first woman to lead the prosecution in a murder trial, and the following year became one of the first two women to be appointed King's Counsel. She was an excellent public speaker, wrote articles for various publications and books on a wide variety of subjects, from Shakespeare to buying a house."

In 1952 Helena Normanton made submissions on behalf of the Married Women's Association to the royal commission on marriage and divorce. She proposed that a husband should pay his wife an allowance from the family income. The MWA complained that this suggestion had been submitted to the royal commission "without previous circulation to executive or members". One member complained that her proposal of a housekeeping allowance for wives equated to "pocket money given to a child". As a result of these criticisms, Normanton resigned as president of the MWA.

Helena Normanton was a pacifist and was a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. She also played a significant role in the campaign for a university in Brighton. In 1956 she made the first donation to the Sussex University appeal. She wrote at the time: "I make this gift in gratitude for all that Brighton did to educate me when I was left an orphan." This was followed by larger donations and she bequeathed the capital of her trust to the university.

On this day in 1961 Harriet Shaw Weaver, who never married, died at Castle End, near Saffron Walden, Essex, and was cremated at Oxford.

Harriet Shaw Weaver, the sixth of eight children of Frederic Poynton Weaver, a doctor, and his wife, Mary Wright, was born in Frodsham, Cheshire, on 1st September 1876. The family was extremely wealthy as her mother having inherited a fortune from her father, made in the cotton industry.

Harriet was educated at home by a governess, Marion Spooner. According to the authors of Dear Miss Weaver (1970): "Her education owed much also to the governess who came when she was ten and remained until she was eighteen and her formal schooling was brought to an end. Miss Marion Spooner was a young gentlewoman of decided powers. She was a good linguist and very musical, though these were qualities to which Harriet and the others, who all had no ear, could not respond. She had a vivid interest in history and in current affairs and pronounced Liberal views. To these Harriet warmed. Under Miss Spooner's tutelage she probably received as broad an education as any single-handed teacher could have given her." Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) added: "Her early influences came from her liberal governess, Marion Spooner, and her own, often secretive, reading." This included The Subjection of Women, a book written by John Stuart Mill and Helen Taylor.

In 1891 the family moved to Hampstead. Three years later, Marion Spooner left, though she was to remain a lifelong friend. Harriet wanted to go to university but her father rejected the idea. "What would be the use of such a course?" He pointed out that she would never need to earn a living and that he was unhappy with the pursuit of a profession for its own sake. Harriet continued to read left-wing books and she became a socialist and a supporter of women's suffrage.

Harriet also did charity work in Bermondsey. In 1902 she became honorary secretary of the East End branch of the Children's Country Holiday Fund. A fellow committee member was Robert Ensor, the author of Modern Socialism (1904) and E. J. Urwick, an economist and political philosopher.

In 1905 Harriet Shaw Weaver began attending lectures at the London School of Sociology and Social Economics that had been founded two years previously by the Charity Organization Society. She also attended a course of lectures on "The Economic Basis of Social Relations" at the London School of Economics. Harriet Weaver also worked with William Beveridge at Toynbee Hall when she was running the East End Branch of the Invalid Children's Aid Association.

Harriet was described during this period by the authors of Dear Miss Weaver: "She was a little above middle height, slim and straight. Her eyes were small, round and a clear blue. Her brown hair, taken back into a bun." One of her contemporaries described her as being "very neat, very austere, like a beautiful nun". Another friend said she was "more reserved than shy" whereas another pointed out that Harriet rarely spoke as she her "urge was to listen". Her sister, Maude Weaver claimed that she had no interest in the other sex, except as human beings, "there was never a flicker of a flirtation with anyone."

Harriet's brother, Harold, died in 1909 after accidentally taking an overdose of sleeping tablets. She later wrote: "What comforted me most when he died... was the thought that it was better to have had him as a dear brother for his short life than not to have had him." Her biographer has pointed out that she "felt his loss acutely" and was "exhausted and unwell for long afterwards". A friend, Edith Munro, wrote to her suggesting that they spend time together: "I know that the light seems to have gone out of your life and nothing seems worth doing or thinking of any more.... Couldn't we go out for a long long walk. I needn't speak at all if you would rather not. If you knew how I longed to be with you. I have loved you so much for so many years and now that you are in trouble I seem quite useless."

Weaver became interested in the subject of women's suffrage and joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). She sold Votes for Women and distributed pamphlets but never took part in any demonstrations and resigned after the start of the arson campaign. She continued to be interested in the struggle for the vote and she began subscribing to The Freewoman. The most controversial aspect of the journal was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden, the editor, began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Grace Jardine, Stella Browne, Edmund Haynes, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Rebecca West, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

Harriet Shaw Weaver was one of those who joined the Freewoman Discussion Circle in London. The authors of Dear Miss Weaver (1970) pointed out: "It was a successful group, inaugurated at a meeting of more than eighty people. The numbers increased so fast that at its first meeting-room, at the Suffragette shop, was too small. So was its second, at the Eustace Miles vegetarian restaurant; and its final home was at the Chandos Hall. The programme for the session July to October 1912 included talks on Eugenics by Mrs Havelock Ellis and on Divorce Reform by E.S.P. Haynes. Other subjects were Sex Oppression and the Way Out, Celibacy, Prostitution, and the Abolition of Domestic Drudgery." Rebecca West recalled that at the meetings: "Everyone behaved beautifully - it's like being in Church, except Rona Robinson and myself. Barbara Low has spoken very seriously to me about it."

In September 1912, The Freewoman was banned by W. H. Smith because "the nature of certain articles which have been appearing lately are such as to render the paper unsuitable to be exposed on the bookstalls for general sale." Dora Marsden argued that this was not the only reason the journal was banned: "The animosity we rouse is not roused on the subject of sex discussion. It is aroused on the question of capitalism. The opposition in the capitalist press only broke out when we began to make it clear that the way out of the sex problem was through the door of the economic problem."

Charles Grenville wrote to Dora Marsden complaining that the journal was losing about £20 a week and told her he was thinking of withdrawing as the publisher of the magazine. Marsden replied: "You have put money into the paper. I have put in the whole of my brain, power and personality. Without your money I would not have started, without my brain the paper could not have lived and shown the signs of flourishing which it undoubtedly has."

The last edition of The Freewoman appeared on 10th October 1912. Dora Marsden told her readers: "The editorial work has not been easy. We have been hemmed in on every side by lack of funds. We have, moreover, been promoting a constructive creed, which had not only to be erected as we went along, we had also to deal with the controversy which this constructive creed left in its wake.... The entire campaign has been carried on indeed only at the cost of a total expenditure of energy, and we, therefore, do not hold it possible to continue the same amount of work, with diminished resources, if in addition, we have to bear the entire anxiety of securing such resources as are to be at our disposal."

Dora appealed to readers to help fund a new magazine. Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw both sent money. Lilian McErie also contributed: "No paper has given me keener pleasure than yours. Its fearlessness and fairness made all lovers and seekers after truth respect it and love it even while differing from many of the opinions expressed therein."

In February 1913 Harriet Shaw Weaver met Dora Marsden, who had just inherited a large sum of money from her father. As Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit, pointed out: "They were in many ways totally unsuited - on the one hand, the rebellious, radical intellectual and on the other, the quiet, modest, unassuming and orderly Weaver. Yet they took an immediate liking towards each other - Weaver impressed by Dora's intelligence and indeed, her beauty, and Dora by Harriet's keen but systematic approach to the re-launch of the paper. Dora had originally just wanted a chat but they ended up in effect having a business meeting while all the time establishing their mutual respect and admiration".

The New Freewoman was launched in June 1913. The journal, published fortnightly, was priced at 6d but readers were asked to pay £1 in advance for 18 months' copies. Dora Marsden wrote in the first edition: "The New Freewoman is not for the advancement of Women, but for the empowering of individuals - men and women.... Editorially, it will endeavour to lay bare the individual basis of all that is most significant in modern movements including feminism. It will continue The Freewoman's policy of ignoring in its discussion all existing taboos in the realms of morality and religion."

Harriet Shaw Weaver put up £200 to fund the magazine and this gave her a controlling interest in the venture. Dora Marsden was editor, Rebecca West assistant editor and Grace Jardine (sub-editor and editorial secretary). The women were all employed on a salary of £1 a week. Later, Ezra Pound, became the journal's literary editor. Weaver's biographer, Rachel Cottam, has argued: "Over the following years she gave regular donations of money, usually anonymously, and became involved in all the details of its organization and finance, finally taking on the role of editor. Though lacking confidence in her own writing, she contributed a number of reviews (signing herself Josephine Wright) and, as editor, wrote the occasional leader article."

Harriet and Dora Marsden became very close. Dora wrote to Harriet claiming that "you have been a perfect treasure to me and the paper". Harriet wrote back expressing her love for Dora. Rebecca West also enjoyed working under Dora, telling her that she was a "wonderful person, you not only write these wonderful first pagers but you inspire other people to write wonderfully."

The New Freewoman gradually moved away from its feminist origins. George Lansbury complained about Marsden's abandonment of socialism and others disliked the emphasis she placed on individualism. Her critics included Rebecca West who resigned her post in October 1913 having become disillusioned with the direction the journal was taking. Later she admitted she strongly disapproved of Dora's "aggressive individualism" and her "egotistic philosophy". Dora replaced Rebecca with the young poet, Richard Aldington.

At a director's meeting on 25th November 1913, it was decided to change the name of the The New Freewoman to The Egoist: An Individualist Review. Bessie Heyes complained to Harriet Shaw Weaver about the change of name. "Don't you yourself think that the paper is not accomplishing what we intend to do? I had such hopes of The New Freewoman and it seems utterly changed." The journal lasted for only seven months and thirteen issues. During this time it only obtained 400 or so regular readers. Ezra Pound wanted the The Egoist to become more of a literary journal. In early 1914 he persuaded Dora Marsden to serialize A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, an experimental novel written by James Joyce.

In the summer of 1914 Dora Marsden handed over the editorship of the journal to Harriet Shaw Weaver. Marsden now assumed the role of contributing editor. This allowed her to concentrate on her philosophical research and writings. However, both women were concerned by the poor sales figures of the journal. After briefly reaching 1,000 copies it had now fallen to a circulation figure of 750.

In January 1916, Harriet Shaw Weaver argued that despite poor sales she was determined to continue supporting the The Egoist. "It has skirted all movements and caught on to none.... The Egoist is wedded to no belief from which it is willing to be divorced. To probe to the depths of human nature, to keep its curiosity in it fresh and alert, to regard nothing in human nature as foreign to it, but to hold itself ready to bring to the surface what may be found, without any pre-determination to fling back all but unwelcome facts - such are the high and uncommon pretensions upon which it bases its claims to provenance."

James Joyce failed to find a publisher for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Harriet Shaw Weaver agreed to establish the Egotist Press and the book was published in February 1917. The book was praised by critics such as H. G. Wells but was attacked by the mainstream press. The editor of The Sunday Express described it as "the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature."

According to Rachel Cottam: "From 1916 Joyce and Weaver corresponded almost daily: she commented on his manuscripts, corrected his proofs, discussed his frustrations and aspirations, and gradually became involved in every aspect of his own and his family's well-being. Though she was aware that he spent money recklessly and sometimes drank to excess, she endeavoured to provide him with an assured family income by transferring him substantial sums of her capital." Rebecca West argued that without Weaver's dedication, it is "doubtful whether Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom would have found their way into the world's mind".

In January 1919 The Egoist: An Individualist Review began the serialization of Joyce's Ulysses. However, sales of the journal had fallen from 1,000 in May 1915 to 400 and Harriet Shaw Weaver, decided to bring the journal to an end.

In 1931, Weaver joined the Labour Party. However, she became a fierce critic of Ramsay MacDonald and his National Government. In 1938 she switched her alliance to the Communist Party of Great Britain. She became a committed member and sold copies of The Daily Worker in the street.

On this day in 1964, the Soviet Central Committee forced Nikita Khrushchev to resign.