On this day on 13th January

On this day in 1691 George Fox, founder of the Religious Society of Friends, died. George, the eldest of four children of Christopher Fox, a weaver, and his wife, formerly Mary Lago, was born in Fenny Drayton in 1624. Both his parents were committed Presbyterians. The family was relatively wealthy. It is believed Fox's father operated two looms while his mother came from a well-off family.

Thomas Ellwood wrote later: "He (Fox) descended of honest and sufficient parents, who endeavoured to bring him up, as they did the rest of their children, in the way and worship of the nation; especially his mother, who was a woman accomplished above most of her degree in the place where she lived... His mother taking notice of his singular temper, and the gravity, wisdom, and piety that very early shone through him, refusing childish and vain sports and company when very young, she was tender and indulgent over him, so that from her he met with little difficulty. As to his employment, he was brought up in country business."

According to his own account Fox shunned the company of other children and "never strayed from the straight and narrow way". In about 1635 Fox's father apprenticed his son to George Gee, a shoemaker who lived in nearby Mancetter. Gee not only trained George in the shoemakers's craft but also let him tend sheep, as well as sell wool and cattle. "An apprenticeship... usually lasted seven years. The apprentice meanwhile resided under his master's roof, ate at his table, and received his instruction, not only about the craft to be learned but also on morals, and sometimes even a degree of formal education."

On 8th September 1643, George Fox shared a jug of beer with a cousin and his friend. After drinking the first pint, the other two decided to see who could drink the most and pledged that the one stopping first had to pay for all the beer consumed. He was amazed that a cousin who shared his own approach to religion could take part in a drinking contest. Fox paid for the whole jug of beer and announced that he would leave rather than have anything to do with this activity: "If it be so. I'll leave you."

The following day Fox broke off his apprenticeship, left home, and went to London, stopping in towns on the way where the Parliamentary Army were garrisoned. At the time the country was in the second year of the English Civil War. Although he sympathised with Parliament over its dispute with King Charles I, Fox refused to take part in the fighting. However, he did take part in the discussions on religion with the soldiers. According to his biographer, H. Larry Ingle, Fox was supportive of the ideas put forward by John Wycliffe and the Lollards more than 250 years earlier.

Wycliffe tried to employ the Christian vision of justice to achieve social change: "It was through the teachings of Christ that men sought to change society, very often against the official priests and bishops in their wealth and pride, and the coercive powers of the Church itself." Barbara Tuchman has claimed that John Wycliffe was the first "modern man". She goes on to argue: "Seen through the telescope of history, he (Wycliffe) was the most significant Englishman of his time."

Fox reached Chipping Barnet on the outskirts of London in June 1644. Approaching his twentieth birthday, Fox wrote in his journal that he was beset by "a temptation to despair". (8) He did not explain what this "temptation" was but it has been suggested that it was sexual desire: "The lure of sexual adventure, in the distant place, in time of war when moral standards tend to decline anyway, and with a willing partner, may well have been the sinful snare that so depressed Fox."

George Fox then moved on to London. At that time the population of the city was about a third of a million, more than 6 per cent of the country's total population. Fox was impressed by some features of the city but appalled by other aspects: "The cheap plays and six-penny whores he would have eschewed on moral grounds, although he might have found diversions in seeing a bear-baiting down at the river or the occasional Indian brought back from the colonies across the Atlantic and put on display."

London was also a hotbed of religious ideas. John Lilburne and the Levellers who were active in the New Model Army, were unhappy with the way that the war was being fought. Whereas they hoped the conflict would lead to political change, this was not true of most of the Parliamentary leaders. "The generals themselves members of the titled nobility, were ardently seeking a compromise with the King. They wavered in their prosecution of the war because they feared that a shattering victory over the King would create an irreparable breach in the old order of things that would ultimately be fatal to their own position."

Lilburne's political activities were reported to Parliament. As a result, he was brought before the Committee of Examinations on 17th May, 1645, and warned about his future behaviour. William Prynne and other leading Presbyterians, such as John Bastwick, were concerned by Lilburne's radicalism. They joined a plot with Denzil Holles against Lilburne. He was arrested and charged with uttering slander against William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons.

Supported by income from his shoemaking skills, Fox wandered into Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. There his anti-clericalism, coinciding with social and political upheaval in the aftermath of the civil war, attracted followers. Fox argued there was no need to rely on human teachers, "Fox preached, for even the scriptures were less authoritative than one's inward guide. He relied on the Bible, which he knew well and whose words were prominent in his teaching and writing, but his stress on the primacy of the Spirit inevitably fed the kind of individualism that greatly hindered lasting unity among his diverse followers. Because the scriptures did not use the term and spoke nothing of it explicitly, he rejected the doctrine of the Trinity, a position bound to alarm and antagonize the orthodox. Nor did he make clear distinctions between the Father and the Son.... He could also find no scriptural justification for paying tithes to a church with which he disagreed, let alone to a private person who might be thus enriched... This cluster of beliefs put Fox beyond the pale of mainstream puritanism. Most of these ideas did occur in the thinking of other contemporary radical sectaries and he was not the first to make a principle of the non-payment of tithes, but he did place this stance more centrally within his teaching than other radicals did."

Fox often preached to members of the New Model Army. So did members of other radical groups such as the Anabaptists and Ranters. This created concern for the Presbyterians and one of its ministers, Richard Baxter, an army chaplain during the war commented: "If they pulled down the parliament, imprisoned the godly, faithful members, and killed the king... if they sought to take down tithes and parish ministers, to the utter confusion of religion in the land, in all these the Anabaptists followed them."

According to Pauline Gregg it was not until 1647 that he came to the simple realization that the spirit of God was within each man, and that the knowledge of Christ was an inner light that could reveal itself at any time without the help of dogma, form, or ceremony. "A man need be equipped with nothing but a humble spirit and a belief in God and Jesus Christ. No prayer-book, no preacher, no sacrament, no church, who needed to guide him - only the witness in his conscience."

Elizabeth Hooton was one of the first people to be "convinced" by Fox after hearing him speak in Nottingham in 1647. Her husband, Oliver Hooten, a prosperous farmer, seems to have opposed his wife's new beliefs "in so much that they had like to have parted". Gerard Croese, a 17th century historian suggested that she "was the first of her sex among the Quakers who attempted to imitate men, and preach" and suggested that she was a role model for women: "after her example, many of her sex had the confidence to undertake the same office". She travelled the country and was arrested and imprisoned several times over the next few years.

On 30th October, 1650, Fox interrupted a church service in Derby. He was arrested and after eight hours of close questioning he was sent to jail for a term of six months for blaspheming. Jails in the 17th century were extremely unpleasant. Jailers charged prisoners fees for better accommodations and food. Jailers were not subject to rules and treated people like Fox who did not share their religious views, very badly. Derby jail was sited over a branch of the River Derwent, exposing its prisoners to damp and filth.

During this period George Fox called his followers "Children of the Light", "People of God", "Royal Seed of God" or "Friends of the Truth". However, one of his critics, Gervase Bennett, described Fox and his followers as Quakers. This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that Fox's followers quaked and trembled during their worship. Fox defended his followers by pointing out that there were numerous biblical figures who were said to have also trembled before the Lord. Later they became known as the "Religious Society of Friends".

On this day in 1844 Catherine Breshkovskaya, the daughter of a prosperous landowner who owned serfs, was born in Vitebsk, Russia. As a child she developed a strong sympathy for the plight of the rural poor: "Men would come to the master begging for bread; women would come weeping, demanding back their children of whom they had been robbed. These things tormented me as a child, pursued me into my bed, where I would lie awake for hours, unable to sleep thinking of all the horrors that surrounded me."

She later told Louise Bryant: "When I think back upon my past life I, first of all, see myself as a tiny five-year-old girl, who was suffering all the time, whose heart was breaking for some one else; now for the driver, then again for the chamber-maid, or the labourer or the oppressed peasant - for at that time there was still serfdom in Russia. The impression of the grief of the people had entered so deeply into my child's soul that it did not leave me during the whole of my life."

Catherine's parents had liberal views and had welcomed the emancipation of the serfs and had encouraged her at the age of sixteen to open a peasant school on their estate. She later recalled "If there is anything good in me, I owe it all to them." However, she was aware that the freed serfs still had considerable problems: "In one village near ours, where the peasants refused to leave their plots, they were drawn up in a line along the village street. Every tenth man was called out and flogged, and some died. Two weeks later, every fifth man was flogged.... I heard many heart-rending stories in my little school house. The peasants would throng to our house night and day."

According to Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976): "After a year of running the school Catherine began desperately to search for some more general political solution to the local misery she saw around her, and at the age of seventeen, after some conflicts with her parents, she set off alone for the capital. In the train to St Petersburg she found herself sitting next to a man who started talking to her of the early populists. They had gone to the countryside, he said, without any idea of social reconstruction in their minds; they simply wanted to teach the peasants to read, to interest them in new ideas, to give them some medical help and to raise them in any way they could from their darkness and misery. In the process, these young people had been able to formulate some of their ideals for a better society." The man she was talking to was Peter Kropotkin.

In St Petersburg Kropotkin introduced Catherine to various radical circles and helped her to get a job as a private teacher. Catherine later recalled that she met several young women, who like her "had won their personal freedom, now wanted to make use of it, not for their own personal enjoyment but to carry to the people the knowledge that had emancipated them."

Under pressure from her parents she returned to Vitebsk where she opened a school for peasant girls. A few years later she met a local wealthy landowner who shared her views. They married and together they established a co-operative bank and a peasant agricultural school on his estate. She was also a regular visitor to Kiev and and with a couple of friends established a socialist commune in Kiev, that had been influenced by the writings of Alexander Herzen, Peter Lavrov and Pavel Axelrod,

After the birth of her son, Nikolai, she left her child with her sister-in-law and became a full-time revolutionary. She later wrote: "I felt that in my child my youth was buried, and that when he was taken from my body, the fire of my spirit had gone out with him. But it was not so... I knew that I could not be a mother and a revolutionary. Among the women involved in the struggle for freedom in Russia there were many who chose to be fighters rather than members of the victims of tyranny."

Catherine Breshkovskaya gave out political leaflets in rural areas: "In one of the villages I gave away my last illegal leaflet and then decided to write an appeal to the peasants myself. Stephanovich made three copies of it... In those terribly ignorant times when the only written papers in the villages were the orders issued by the authorities, their faith in a written word was great, all the more so since there was no one in the villages who could write even moderately well."

Breshkovskaya was eventually arrested by the authorities and after being held in solitary confinement in Kiev Prison for a year. In January, 1878, Breshkovskaya and thirty-six other women were tried for carrying out "revolutionary propaganda". She was found guilty and sentenced to twenty years hard labour in Siberia. She became a well-known international figure when she was interviewed by the American journalist, George Kennan for his book Siberia and the Exile System.

In 1896 Breshkovskaya was allowed to return home and it was not long before she became involved in politics again. Breshkovskaya, like Alexander Herzen believed that any socialist revolution in Russia would have to be instigated by the peasantry. According to Edward Acton, the author of Alexander Herzen and the Role of the Intellectual Revolutionary (1979): "Nineteenth-century Russia was overwhelmingly a peasant society, and it was to the peasantry that Herzen looked for revolutionary upheaval and socialist construction. Central to his vision was the existence of the Russian peasant commune. In most parts of the empire the peasantry lived in small village communes where the land was owned by the commune and was periodically redistributed among individual households along egalitarian lines. In this he saw the embryo of a socialist society. If the economic burdens of serfdom and state taxation were to be removed, and the land of the nobility made over to the communes, they would develop into flourishing socialist cells."

In 1901 Breshkovskaya joined with Victor Chernov, Gregory Gershuni, Nikolai Avksentiev, Alexander Kerensky and Evno Azef, to form the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR) and spent much of her time touring the world making speeches and raising money for the party. The main policy of the SR was the confiscation of all land. This would then be distributed among the peasants according to need. The party was also in favour of the establishment of a democratically elected constituent assembly and a maximum 8-hour day for factory workers.

Catherine Breshkovskaya was arrested in 1907 and was sentenced to be exiled to Siberia for life. She was only released after the fall of the overthrow of Nicholas II. When she arrived back in St Petersburg she supported the Provisional Government, that included two members of the SR, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice and Victor Chernov Minister of Agriculture.

In July 1917, Kerensky became prime minister. He invited Breshkovskaya to become one of his advisers and arranged for her to live in the Winter Palace. The journalist, Louise Bryant interviewed Breshkovskaya for her book, Six Months in Russia (1918): "I saw Babushka a good many times after that and found why she lived in this back room on the top floor of the Winter Palace. First, it was because she chose to live there. They had offered her the choice of the beautiful apartments and she had refused anything but this simple room. She insisted on having her bed and all her belongings crammed into the tiny place, and ate all her meals there. I don't know whether it was her long years in prison that made her assume this peculiar attitude, or if it was just because she was a simple woman and very close to the people."

Babushka told Bryant that she was looking forward to the elections for the Constituent Assembly which she believed would result in a victory for the Socialist Revolutionary Party and that Alexander Kerensky would be Russia's first President. However, Kerensky's was overthrown by the Bolsheviks on 24th October, 1917. Lenin, the new leader of the country, gave instructions for elections to the assembly.

The balloting began on 25th November and continued until 9th December. Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17). As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie."

Lenin was bitterly disappointed with the result as he hoped it would legitimize the October Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. Nikolai Sukhanov argued: "Without Chernov the SR Party would not have existed, any more than the Bolshevik Party without Lenin - inasmuch as no serious political organization can take shape round an intellectual vacuum. But Chernov - unlike Lenin - only performed half the work in the SR Party. During the period of pre-Revolutionary conspiracy he was not the party organizing centre, and in the broad area of the revolution, in spite of his vast authority amongst the SRs, Chernov proved bankrupt as a political leader. Chernov never showed the slightest stability, striking power, or fighting ability - qualities vital for a political leader in a revolutionary situation. He proved inwardly feeble and outwardly unattractive, disagreeable and ridiculous."

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia.

Catherine Breshkovskaya was upset by these events and decided to live in Czechoslovakia. Breshkovskaya founded Russian-language schools in Ruthenia before retiring to Khvaly, where she died on 12th September 1934.

On this day in 1893 the Independent Labour Party holds its first meeting. In the 1880s working-class political representatives stood in parliamentary elections as Liberal-Labour candidates. After the 1885 General Election there were eleven of these Liberal-Labour MPs. Some socialists like Keir Hardie, the Liberal-Labour MP for West Ham, began to argue that the working class needed their own independent political party. This feeling was strong in Manchester and in 1892 Robert Blatchford, the editor of the socialist newspaper, the Clarion joined with Tom Garrs, and Richard Pankhurst to form the Manchester Independent Labour Party.

The activities of the Manchester group inspired Liberal-Labour MPs to consider establishing a new national working class party. Under the leadership of Keir Hardie, the Independent Labour Party was formed in January 1893. It was decided that the main objective of the party would be "to secure the collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". Leading figures in this new organisation included Hardie, Robert Smillie, George Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann, George Barnes, John Glasier, H. H. Champion, Ben Tillett, Philip Snowden, Edward Carpenter and Ramsay Macdonald.

In 1895 the Independent Labour Party had 35,000 members. However, in the 1895 General Election the ILP put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. All the candidates were defeated but the ILP began to have success in local elections. Over 600 won seats on borough councils and in 1898 the ILP joined with the the Social Democratic Federation to make West Ham the first local authority to have a Labour majority.

The example of West Ham convinced Keir Hardie that to obtain national electoral success, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups. On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain (the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society, joined trade union leaders to form the Labour Representation Committee (the Labour Party).

On this day in 1914 Beatrice Harraden writes a letter to Christabel Pankhurst accusing her of alienating too many old colleagues by her dictatorial behaviour. "It must be that... your exile (in Paris) prevents you from being in real touch with facts as they are over here."

Several friends were worried about Christabel's mental state. A number of significant figures in the WSPU left the organisation over the arson campaign. This included Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford, Laura Ainsworth, Eveline Haverfield and Louisa Garrett Anderson. Leaders of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage such as Henry N. Brailsford, Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman, argued "that militancy had been taken to foolish extremes and was now damaging the cause".

Hertha Ayrton, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Janie Allan and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson stopped providing much needed money for the organization. Colonel Linley Blathwayt and Emily Blathwayt also cut off funds to the WSPU. In June 1913 a house had been burned down close to Eagle House. Under pressure from her parents, Mary Blathwayt resigned from the WSPU.

In February 1914, Christabel expelled Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst from the WSPU for refusing to follow orders. Henry Harben complained that her autocratic behaviour had destroyed the WSPU: "People are saying that from the leader of a great movement you are developing into the ringleader of a little rebel Rump." According to Martin Pugh "she had fallen into the error of all autocratic leaders; her power to manipulate personnel was so complete that it left her increasingly surrounded by sycophants who lacked real ability."

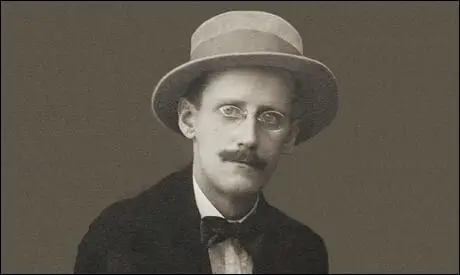

On this day in 1941 James Joyce died after an operation on a duodenal ulcer. James Joyce was born in Dublin in 1882. Educated at Jesuit schools he studied modern languages at University College. While still at university Joyce had an article on Ibsen published in the Fortnightly Review. He also become friendly with other literary figures in the city including J. M. Synge and W. B. Yeats.

After graduating in 1902 Joyce moved to France. He returned to Ireland after the death of his mother. In 1904 Joyce met Nora Barnacle and the couple went to live in Switzerland. The following year they moved to Trieste where Joyce found work at the Berlitz School.

During the First World War Joyce moved to Zurich where he began work on his next novel, Ulysses. It was published in serial form in the New York journal, The Little Review (April 1918 to December 1920). As a result of the serialization the journal was prosecuted for publishing obscene matter. It was eventually published in France in 1922 but was impounded by customs officials when attempts were made to import the book into England. When the books arrived in the United States they were seized and burnt by the postal authorities.

Poems Penyeach, a small collection of poems, appeared in 1927. Despite Ulysses being praised by writers such as W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, Ernest Hemingway and Arnold Bennett it was not published in Britain until 1936. This was followed by Finnegans Wake in 1939.