On this day on 8th May

On this day in 1869 Flora Murray was born. She trained at the London School of Medicine for Women and finished her course at Durham. She then worked in Scotland before returning to London in 1905. She was a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children and then anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women.

In November 1908 she signed a petition sponsored by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Soon afterwards she joined the Women Social & Political Union. It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Murray was a lesbian and lived for many years with Elsie Inglis.

In 1909 she stood surety for Marion Wallace-Dunlop. She attended several demonstrations where along with her great friend, Louisa Garrett Anderson, she helped treat those members of WSPU who were injured. She was also involved with Anderson and Catherine Pine in running the Notting Hill nursing home that WSPU members went to while recovering from hunger strikes. In 1912 the two women established the Women's Hospital for Children in the Harrow Road.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

During the First World War a group of wealthy suffragettes, including Janie Allan, decided to fund the Women's Hospital Corps. Murray joined forces with Louisa Garrett Anderson to run a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. Fellow WSPU member, Evelyn Sharp, who visited them in France, remarked: "It was in a way a triumph for the militant movement that these two doctors, who had been prominent members of the W.S.P.U., were the first to break down the prejudice of the British War Office against accepting the services of women surgeons." In February 1915 Anderson and Murray took charge of the Endell Street Military Hospital in London. Anderson was chief surgeon and the hospital treated 26,000 patients before it closed in 1919.

Flora Murray never married and was the constant companion of Louisa Garrett Anderson until her death from rectal carcinoma in 1923. She was buried in the churchyard at Holy Trinity Church near to her home in Penn, Buckinghamshire.

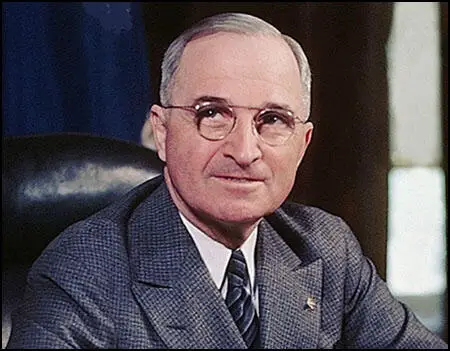

On this day in 1884 Harry S. Truman, to son of a farmer, was born in Lamar, Missouri. After an education in Independence, he farmed on his parents' land. In 1917, soon after the United States entered the First World War, he enlisted in the army. Truman served on the Western Front and achieved the rank of captain.

On returning from the war Truman ran an unsuccessful haberdashery before studying law in Kansas City. Truman became active in local politics. A great admirer of Woodrow Wilson, Truman joined the Democratic Party and in 1922 was elected county judge (1922-24). This was followed by eight years as presiding judge, a post he held until being elected to the Senate in 1934.

Truman loyally supported Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal policies, and in 1944 he was asked to replace Henry Wallace as his vice president. Truman only served 82 days as vice president when Roosevelt died on 12th April, 1945. In his first address to Congress he promised to continue Roosevelt's policies. In July he attended the Potsdam Conference and in August authorized the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima.

Henry Wallace, Secretary of Commerce, favoured co-operation with the Soviet Union. In private he disagreed with Truman about what he considered to be an aggressive foreign policy. Wallace went public about his fears at a meeting in New York City in September, 1946. As a result, Truman sacked Wallace from his administration.

On 12th March, 1947, Truman announced details to Congress of what eventually became known as the Truman Doctrine. In his speech he pledged American support for "free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures". This was followed by the Marshall Plan, a proposal to offer American financial aid for a programme of European economic recovery.

Truman showed a stronger interest in civil rights than previous presidents. He was a proud defender of the Fair Employment Act that he had instigated during the war to prevent discrimination against African Americans, Jews and other minority groups. A supporter of the Wagner Act, he opposed the Taft-Hartley Bill which limited labour action, claiming it was bad for industry and workers alike. When Congress passed it he denounced it as a "slave-labor bill".

At the Democratic National Convention of 1948, Storm Thurmond led the opposition to Truman and his Fair Deal proposals that included legislation on civil rights, fair employment practices, opposition to lynching and improvements in existing public welfare laws. When Truman won the nomination, Southern Democrats formed the States' Rights Democratic Party (Dixiecrats) and Thurmond was chosen as its presidential candidate.

It was thought that with two former Democrats, Strom Thurmond and Henry Wallace standing, Truman would have difficulty defeating the Republican Party candidate, Thomas Dewey. However, both Thurmond and Wallace did badly and Truman defeated Dewey by 24,105,812 votes to 21,970,065.

Truman had difficulty getting Congress to pass his Fair Deal program and most of these measures were not enacted during his term in office. He was criticised for not doing more to halt the activities of Joe McCarthy. After losing power, Truman described McCarthyism as: "The use of the big lie and the unfounded accusation against any citizen in the name of Americanism or security. It is the rise to power of the demagogue who lives on untruth; it is the spreading of fear and the destruction of faith in every level of society."

In 1950 group of Conservative senators, including Pat McCarran, John Wood, Karl Mundt and Richard Nixon sponsored a measure to deal with members of the Communist Party. Truman opposed the measure arguing that it "would betray our finest traditions" as it attempted to "curb the simple expression of opinion". He went on to argue that the "stifling of the free expression of opinion is a long step toward totalitarianism." Congress overrode Truman's veto by large margins: House of Representatives (248-48) and the Senate (57-10) and the Internal Security Act became law in 1950.

On 25th June, 1950, communist forces in North Korea invaded the Republic of South Korea, crossing the 38th parallel at several points. Harry S. Truman immediately announced that he would use American forces for the defence of South Korea.

Truman upset conservative forces in the United States when he took the side of Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, in his dispute with General Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War. Acheson and Truman wanted to limit the war to Korea whereas MacArthur called for the extension of the war to China. Joe McCarthy once again led the attack on the administration: "With half a million Communists in Korea killing American men, Acheson says, 'Now let's be calm, let's do nothing'. It is like advising a man whose family is being killed not to take hasty action for fear he might alienate the affection of the murders."

In April 1951, Truman removed General Douglas MacArthur from his command of the United Nations forces in Korea. McCarthy called for Truman to be impeached and suggested that the president was drunk when he made the decision to fire MacArthur: "Truman is surrounded by the Jessups, the Achesons, the old Hiss crowd. Most of the tragic things are done at 1.30 and 2 o'clock in the morning when they've had time to get the President cheerful."

Dean Acheson was the main target of McCarthy's anger as he believed Truman was "essentially just as loyal as the average American". However, Truman was president "in name only because the Acheson group has almost hypnotic powers over him. We must impeach Acheson, the heart of the octopus."

In 1952 Truman decided not to stand again and retired to private life, publishing two volumes of Memoirs in 1955 and 1956.

Harry S. Truman died on 26th December, 1972.

On this day in 1928 Theodore (Ted) Sorensen, the son of a Danish father and a Russian-Jewish mother, was born in Lincoln, Nebraska. He studied at the University of Nebraska where he graduated first in the class in 1949. He took a keen interest in politics and as a young man he had been influenced by the career of George Norris.

Sorensen developed left-wing political views and was member of the Americans for Democratic Action. He then went on to obtain a law degree from Nebraska's College of Law. Sorensen moved to Washington where he was an attorney with the Federal Security Agency (1951-53).

Sorensen did some Senate committee staff work for Paul H. Douglas of Illinois. Douglas introduced Sorensen to the recently elected John F. Kennedy. Another colleague, Pierre Salinger claimed: "They hit it off magnificently. Sorensen not only had strong social convictions echoing those of the young senator, but a genius for translating them into eloquent and persuasive language." According to Godfrey Hodgson: "He worked very closely for eight years with Kennedy, travelled with him, shared his political aims and ambitions and acquired a deep and instinctive understanding of Kennedy's sometimes idiosyncratic political philosophy."

In 1956, Kennedy won a Pulitzer Prize for his book, Profiles in Courage. Rumours began to circulate that the book had actually been written by Sorensen. The following year, the investigative journalist, Drew Pearson, wrote: "Jack Kennedy is the only man in history that I know who won a Pulitzer prize on a book which was ghostwritten for him." Kennedy fiercely denied it, and Sorensen signed an affidavit confirming Kennedy's story that the book was all his own work. Kennedy later offered, and Sorensen accepted, a substantial sum as his share in the proceeds of the book.

In 1960 John F. Kennedy appointed Sorensen as his chief speechwriter. He is believed to have been the main contributor to Kennedy's inaugural address. Richard J. Tofel of the Wall Street Journal did a detailed analysis of the speech and has argued that Kennedy was responsible for no more than 14 of the speech's 51 sentences, and that "if we must identify one man as the author of that speech, that man must surely be not John Kennedy but Theodore Sorensen."

Sorenson, who was officially Kennedy's special counsel, wrote a large number of Kennedy's speeches. He was also the coordinator of planning for domestic policy and had a key role in formulating Kennedy's recommendations to Congress. Sorensen was also a member of the executive committee that Kennedy set up to advise him during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. Later Sorensen claimed that the work of which he was most proud was his contribution to the messages the president sent to the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, during the crisis. He was also the author of Decision Making in the White House (1963)

The assassination of John F. Kennedy was according to Sorensen "the most deeply traumatic experience of my life." He immediately sent a letter of resignation to President Lyndon Johnson but was persuaded to stay on as his speechwriter. Sorensen eventually left in February 1964.

Sorensen joined the New York City law firm, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, and wrote several books, including Kennedy (1965) and The Kennedy Legacy (1969). He was also one of the key political advisers to Robert Kennedy in his bid for the presidency in 1968. He also helped Edward Kennedy with his speech following the death of Mary Jo Kopechne.

In 1977 President Jimmy Carter nominated Sorensen as director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Carter withdrew the nomination after he discovered that the Senate had grave doubts about his suitability for the job. This was because of his past membership of the Americans for Democratic Action and his registration as a conscientious objector in 1946.

Other books by Ted Sorensen included Watchmen in the Night: Presidential Accountability After Watergate (1975), Different Kind of Presidency: A Proposal for Breaking the Political Deadlock (1984), Let the Word Go Forth: The Speeches, Statements, and Writings of John F. Kennedy (1988), The Kennedy Legacy: A Peaceful Revolution for the Future (1993), Why I Am a Democrat (1996) and Leaders of Our Time: Kennedy (1999). His autobiography, Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History was published in 2008.

Ted Sorensen died on 31st October, 2010.

On this day in 1939 Duke of Windsor made a radio broadcast in Paris condemning Neville Chamberlain for introducing conscription. "I speak for no one but myself and without the previous knowledge of any government. I speak simply as a soldier of the last war whose most earnest prayer is that such cruel and destructive madness shall never again overtake mankind. I break my self-imposed silence now only because of the manifest danger that we may all be drawing nearer a repetition of the grim events which happened a quarter of a century ago. You and I know that Peace is a matter far too vital for our happiness to be treated as a political question. We also know that in modern warfare victory will only lie with the powers of evil."

Over 400,000,000 people heard the broadcast and was much discussed in the rest of the world. However, it has remained entirely unknown in Britain as it was banned by the BBC on the orders of Chamberlain. The Duke of Windsor used his contacts in the American broadcasting network and the speech was leaked to journalists all over the world. However, it remained banned in Britain. The way this information was suppressed indicated the way censorship would work during the Second World War.

On this day in 1943 Mordechai Anielewicz is murdered at Treblinka. Mordecai Anielewicz was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1919. After finishing secondary school Anielewicz joined the Zionist movement and became a full-time organizer of the movement. When the German Army invaded Poland in September 1939, Anielewicz managed to escape to Romania.

In October 1939, the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) began to deport Jews living in Austria and Czechoslovakia to ghettos in Poland. Transported in locked passenger trains, large numbers died on the journey. Those that survived the journey were told by Adolf Eichmann, the head of the Gestapo's Department of Jewish Affairs: "There are no apartments and no houses - if you build your homes you will have a roof over your head."

In Warsaw all 22 entrances to the ghetto were sealed. The German authorities allowed a Jewish Council (Judenrat) of 24 men to form its own police to maintain order in the ghetto. The Judenrat was also responsible for organizing the labour battalions demanded by the German authorities. Conditions in the Warsaw ghetto were so bad that between 1940 and 1942 an estimated 100,000 Jews died of starvation and disease in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Anielewicz returned to Warsaw where he attempted to organize resistance to the Nazi occupation and in November 1942 was elected as chief commander of the Jewish Fighter Organization in the ghetto.

Between 22nd July and 3rd October 1942, 310,322 Jews were deported from the Warsaw ghetto to extermination camps. Information got back to the ghetto what was happening to those people and it was decided to resist any further attempts at deportation. In January 1943, Heinrich Himmler gave instructions for Warsaw to be "Jew free" by Hitler's birthday on 20th April.

Anielewicz now played a prominent role in organizing resistance in Warsaw. On 19th April 1943, the Waffen SS entered the ghetto. Although though only had two machine-guns, fifteen rifles and 500 pistols, the Jews opened fire on the soldiers. They also attacked them with grenades and petrol bombs. The Germans took heavy casualties on the first day and the Warsaw military commander, Brigadier-General Jürgen Stroop, ordered his men to retreat. He then gave instructions for all the buildings in the ghetto to be set on fire.

As people fled from the fires they were rounded up and deported to the extermination camp at Treblinka. The ghetto fighters continued the battle from the cellars and attics of Warsaw. On 8th May the Germans began using poison gas on the insurgents in the last fortified bunker. About a hundred men and women escaped into the sewers but the rest were killed by the gas, including Mordechai Anielewicz.

On this day in 1944 women's suffragist, Ethel Smyth, died.

Ethel Smyth, the fourth of the eight children of Major-General John Hall Smyth (1815–1894) and his wife, Emma Struth Smythe (1824–1891), was born at 5 Lower Seymour Street, London, on 22nd April 1858. In her autobiography she claimed that her father was very strict: "I think on the whole we were a naughty and very quarrelsome crew... Of course we merited and came in for a good deal of punishment, including having our ears boxed, which in those days was not considered dangerous... I think I am the only one of the six Miss Smyths who has ever been really thrashed; the crime was stealing some barley sugar, and though caught in the very act, persistently denying the theft. Thereupon my father beat me with one of grandmama's knitting needles, a thing about two and a half feet long with an ivory knob at one end.... Hit hard he did, for a fortnight later, when I joined Alice, who had been away all this time at an aunt's, she noticed strange marks on my person while bathing me, and was informed by me that it came from sitting on my crinoline... Even in after years my mother could not bear to think about that thrashing."

Ethel was much closer to her mother: "At this stage of my existence I stood in great awe of my father, but adored my mother, and remember her dazzling apparitions at our bedside when she would come to kiss us good-night before starting for an evening party. I often lay sleepless and weeping at the thought of her one day growing old and less beautiful. Besides this, wild passions for girls and women a great deal older than myself made up a large part of my emotional life, and it was my habit to increase the anguish of love by fancying its object was prey to some terrible disease that would shortly snatch her from me."

Emma Struth Smythe introduced her daughter to music: "She was in fact one of the most naturally musical people I have ever known; how deeply so I found out in after years when she came to Leipzig to see me, and I watched her listening for the first time to a Beethoven symphony - watched her face softening, tightening, relaxing again as each beauty I specially counted on went home. Old friends maintained that when she was young her singing would have melted a stone, which I can well believe all the warm, living qualities that made her so lovable must have got into it. When I knew her she had almost lost her voice, but enough remained to judge of its strangely moving timbre. Later on she loved to hear me sing, and it saddens me to think how seldom I gratified her when we were by ourselves; but I always was lazy about singing."

Her biographer, Elizabeth Kertesz, has pointed out: "She first became aware of her musical vocation in 1870, under the influence of a governess who had studied at the Leipzig conservatory. She was educated at home, with her five sisters, but was sent to school in Putney between 1872 and 1875. In spite of musical activities at school, she did not really begin to develop her talent until she returned to Frimley and received tuition from Alexander Ewing. This new friend and mentor encouraged her musical aspirations, while his wife, Juliana, foretold an author's career for their enthusiastic pupil. The fruitful contact was brought to an abrupt end by General Smyth's distrust of Ewing, but Smyth had already made up her mind to study composition in Leipzig."

However, Major-General John Hall Smyth refused permission for her to study music and insisted that she got married. According to Kertesz: "With her goal set, Smyth chafed at the social obligations of a marriageable young woman. She had tacit support from her mother, but quarrelled violently with her disapproving father and eventually resorted to militant tactics, locking herself in her room and refusing to attend social engagements. General Smyth finally agreed to her demand and she set off for Leipzig in July 1877. This was indeed a victory for a young woman of her class."

Ethel Smyth found Leipzig Conservatory disappointing and after a year she abandoned this institution to study privately with the composer Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843–1900). Herzogenberg's wife, Lisl, became Smyth's first great love and the two women grew very close. Another biographer, Ronald Crichton, has commented: "On the whole it seems that the greatest and most enduring of her 'passions' were for older women with whom, through character or circumstance or both, physical gratification was out of the question even to one of her on-coming disposition."

Ethel Smyth claimed in her autobiography, Impressions that Remained (1919): "The moment has come to express regret that unlike other women writers of memoirs, such as Sophie Kowalewski, George Sand and Marie Bashkirtseff - if for a moment I may class myself with such as these - I have so far no orthodox love-affairs to relate, neither soulful sentiment for musician of genius, nor perilous passion conceived among the reeds of the Crostewitz lake for proud Prussian guardsman. In my letters to Lisl, where all the secrets of my heart stand revealed, I again and again express a conviction it is foolish to insist upon, so obvious is it, that the most perfect relation of all must be the love between man and woman, but this seemed to me, given my life and outlook, probably an unachievable thing."

In 1878 she went to live with the Herzogenberg family. Heinrich von Herzogenberg introduced Ethel to Johannes Brahms. She later recalled: "To my mingled delight and horror I learned, too, that Henschel had actually spoken to him about my work, telling him I had never studied, that he really ought to look at it and so on; and after the general rehearsal this good friend clutched and presented me all unawares. At that time Brahms was clean shaven, and in the whirl of emotion I only remember a strong alarming face, very penetrating bright blue eyes, and my own desire to sink through the floor when he said, as I then thought by way of a compliment, but as I now know in a spirit of scathing irony, So this is the young lady who writes sonatas and doesn't know counterpoint!"

In 1882 Ethel Smyth met Lisl Herzogenberg's sister Julia and her husband, Henry B. Brewster (1850–1908) in Florence. Brewster was an American writer and philosopher who had grown up in Europe. In her autobiography Impressions that Remained (1919) she pointed out: "It may be remembered that the Brewsters held unusual views concerning the bond between man and wife, views which up to the time of my arrival on the scene had not been put to the proof by the touch of reality. My second visit to Florence was fated to supply the test. Harry Brewster and I, two natures to all appearance diametrically opposed, had gradually come to realize that our roots were in the same soil - and this I think is the real meaning of the phrase to complete one another - that there was between us one of those links that are part of the Eternity which lies behind and before Time. A chance wind having fanned and revealed at the last moment, as so often happens, what had long been smouldering in either heart, unsuspected by the other, the situation had been frankly faced and discussed by all three of us; and I then learned, to my astonishment, that his feeling for me was of long standing, and that the present eventuality had not only been foreseen by Julia from the first, but frequently discussed between them. To sum up the position as baldly as possible, Julia, who believed the whole thing to be imaginary on both sides, maintained it was incumbent on us to establish, in the course of further intercourse, whether realities or illusions were in question. After that - and surely there was no hurry - the next step could be decided on. This view H. B. allowed was reasonable. My position, however, was that there could be no next step, inasmuch as it was my obvious duty to break off intercourse with him at once and for ever. And when I left Italy that chapter was closed as far as I was concerned." Her biographer, Elizabeth Kertesz, has argued: "She returned to Italy the following winter and found herself reciprocating Brewster's growing affection for her, although she tried to act honourably by breaking off all contact with him. Despite this renunciation, Lisl's loyalties were torn, and in 1885 she severed all contact with Smyth."

Ethel Smyth began to make a name for herself as a composer during this period. She wrote piano music and works for a variety of chamber ensembles in a style strongly influenced by the Brahmsian tradition. Most of these works were performed privately, but her string quintet (op. 1, 1883) and her violin sonata (op. 7, 1887) were played publicly at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. She returned to England, where no one knew of her German success. Ethel also had a great voice. Maurice Baring described her singing as "the rare and exquisite quality and deelicacy of her voice, the strange thrill and wail, the distinction and distinct, clear utterance".

In 1889 Ethel Smyth launched herself on the English musical scene with performances at the Crystal Palace of her Serenade in D and her Overture to Antony and Cleopatra . This was followed by the première of her Mass in D, performed by the Royal Choral Society and premiered at the Royal Albert Hallby the Royal Choral Society in 1893. These works established Smyth as the most important woman composer of her time. Claire Tomalin has argued: "Ethel's work did not stand in the way of her social activities, or her many passionate friendships. Throughout her life, she loved intensely, without regard to age or gender... She did defy - or perhaps rather ignore - all the stereotypes of her time, whether in matters of work, sex, class or even manners.... Over the next two decades she studied, composed and met most of the great figures of the day."

After Julia Brewster died in 1895 Ethel and Brewster were able to pursue their relationship more openly. Maurice Baring was a close friend: "His (Harry Brewster) appearance was striking; he had a fair beard and the eyes of a seer... someone said he looked like a Rembrandt. His manner was suave, and at first one thought him inscrutable - a person whom one could never know, surrounded as it were by a hedge of roses. When I got to know him better I found the whole secret of Brewster was this: he was absolutely himself; he said quite simply and calmly what he thought, and the truth is sometimes disconcerting when calmly expressed." According to Elizabeth Kertesz: "They neither married nor had children, and retained separate homes - she in England, he in Italy - but Brewster was a stable presence in Smyth's often stormy life.... his importance to her unaltered by her concurrent relationships with women." Ethel claimed that "Harry was never jealous of my women friends, in fact he held, as I do, that every new affection that comes into your life enriches older ties".

Smyth also wrote operas such as Der Wald (1901). Her work was difficult and her friend, Mabel Dodge, hired the His Majesty's Theatre for six performances of The Wreckers, a work that she had written with Henry B. Brewster. Smythe managed to persuade Thomas Beecham to conduct the work. Smyth had difficulty working with Beecham: "As the rehearsals wore on I discovered that in more respects than one my new friend was a disconcerting person to work with. For one thing he was never less than half an hour late, a habit which in that department of music life bears cruelly on all concerned. I also noticed that not only was it an effort to him to allow for the limitations of the human voice, to give the singers time to enunciate and drive home their words, but that qua musical instrument he really disliked the genus singer, which seemed an unfortunate trait in an opera conductor. In short, my impression was that his real passion was concert rather than opera conducting."

In his autobiography, A Mingled Chime (1944), Beecham explained why the opera was rarely produced: "This fine piece (The Wreckers) has never had a convincing representation owing to the apparent impossibility of finding an Anglo-Saxon soprano who can interpret revealingly that splendid and original figure, the tragic heroine Thirza. Neither in this part nor that of Mark, the tenor, have I heard or seen more than a tithe of that intensity and spiritual exaltation without which these two characters must fail to make their mark."

Ethel Smyth was a passionate supporter of women's rights and was a close friend of the three sisters, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Agnes Garrett. All the women were members of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Ethel went to live with them at Firs Cottage, in the village of Rustington. As Ethel pointed out: "Agnes and Rhoda Garrett, who were among the first women in England to start business on their own account and by that time were well-known house decorators of the Morris school... Both women were a good deal older than I, how much I never knew - nor wished to know, for Rhoda and I agreed that age and income are relative things concerning which statistics are tiresome and misleading."

Ethel Smyth met Emmeline Pankhurst in the summer of 1910. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause (2003), has argued: "Ethel Smyth, an endearingly eccentric bisexual composer who cheerfully confessed to having little or no political background and to caring even less about votes for women - until she met and fell passionately in love with the founder of the WSPU. At first glance Ethel Smyth made a curious companion for a political leader who, despite the violence which attached itself to her movement, remained resolutely feminine. While Emmeline usually had some lace about her person Ethel always dressed in tweeds, deerstalker and tie. Emmeline tended to attack every venture with passion while her new friend regarded the world with a wry, amused cynicism. Ethel, unlike Emmeline, had few sexual or personal inhibitions. But the two women, who at fifty-two were exactly the same age, immediately formed so close an attachment that Ethel decided to give two years of her life to the cause."

Smyth joined the Women's Social and Political Union and the following year she composed the WSPU battle song, The March of the Women. In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Smythe took part in these activities and was with Emmeline Pankhurst when they were arrested: "The Downing Street window selected by Mrs Pankhurst was duly bombarded - I think she had two shots at it before they arrested her - but the stones never got anywhere near the objective. I broke my window successfully and was bailed out of Vine Street at midnight by wonderful Mr Pethick-Lawrence, who was ever ready to take root in any police station, his money bag between his feet, at any hour of the day or night."

Ethel Smyth was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933) she wrote: "The ensuing two months in Holloway, though one never got accustomed to an unpleasant sensation when the iron door was slammed and the key turned, were as nothing to me because Mrs Pankhurst was in with us. The merciful matron put us in adjoining cells, and at exercise, in chapel and on such other occasions as a kind-hearted matron can make for a prisoner, we saw more of each other than the protocol permitted. For instance she would often leave us together in Mrs Pankhurst's cell at tea-time 'just for a moment', lock us in, and forget to come back and conduct me to my own. But, as with policemen and detectives, Mrs Pankhurst refused to be softened by these favours, or by obviously sincere protestations of the 'it-hurts-me-more-than-it-hurts-you' order. And when, with an accent of cold scorn, she said, 'I would throw up any job rather than treat women as you say it is your didy to treat us,' the worst of it was that everyone knew this was nothing but the truth. According to Fran Abrams: "Ethel helped to organise athletic sports in the prison yard, which was even decorated by the women in the suffragette colours. As the women marched around the exercise yard singing March of the Women, an anthem she had composed for them, Ethel looked on from the window of her cell, marking time with a toothbrush."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Ethel Smyth has pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Smythe was a lesbian and that she was probably the lover of Emmeline Pankhurst, Edith Craig and Christabel Marshall. She also became involved with Virginia Woolf, who wrote in her diary: "An old woman of seventy-one has fallen in love with me... It is like being caught by a giant crab."

In 1922 Ethel Smyth was reated a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She also wrote two volumes of autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933) and What Happened Next (1940).

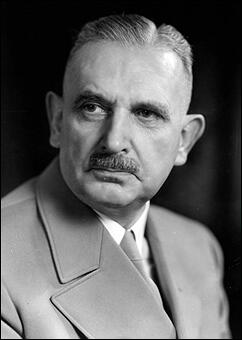

On this day in 1945 Bernhard Rust commits suicide when it was clear that Germany had lost the war. Bernhard Rust was born in Hannover, Germany, on 30th September, 1883. After studying philosophy, philology, art history and music at Munich, Göttingen, Berlin and Halle, he became a secondary schoolteacher in his home town.

Rust joined the German Army in the First World War and won the Iron Cross for bravery. He reached the rank of lieutenant before he received a bad head wound that it was later claimed affected his mental stability.

In 1922 Rust joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). He made good progress in the party and in 1925 was appointed Gauleiter of Hanover-Braunschweig. Rust lost his job as a schoolteacher in 1930 after being accused of having a sexual relationship with a student. He was not charged with the offence because of his "instability of mind". However, this did not stop him being elected to the Reichstag later that year.

When Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933 he appointed Rust as Minister of Science, Art, and Education for Prussia. In a speech he made on 6th November, 1933, Adolf Hitler, announced what he intended to do with the education system: "When an opponent declares I will not come over to your side. I calmly say, Your child belongs to us already. What are you? You will pass on. Your descendants, however, now stand in the new camp. In a short time they will know nothing else but this new community."

In 1934 he was promoted to the post of Education Minister for the Reich. Rust's task was to change the education system so that resistance to fascist ideas were kept to a minimum. Teachers who were known to be critical of the Nazi Party were dismissed and the rest were sent away to be trained in National Socialist principles. As a further precaution schools could only use textbooks that have been approved by the party. On one occasion he remarked that "the whole function of education is to create Nazis."

Rust introduced a Nazi National Curriculum. Considerable emphasis was placed on physical training. Boxing was made compulsory in upper schools and PT became an examination subject for grammar-school entry as well as for the school-leaving certificate. Persistently unsatisfactory performance at PT constituted grounds for expulsion from school and for debarment from further studies. In 1936 timetable allocation of PT periods was increased from two to three. Two years later it was increased to five periods. All teachers below the age of fifty were pressed into compulsory PT courses.

Other subjects to be upgraded were history, biology and German. The importance of biology was derived from the special emphasis the regime placed on race and heredity. Pupils were trained to measure their skulls and to classify each other's racial types. There were also courses on the origins of the Nazi Party and racial science. The amount of time on religious instruction was reduced and it ceased to be a subject for school-leaving examinations and attendance at school prayers was made optional. Prayers written by Baldur von Schirach, the head of the Hitler Youth, that praised Adolf Hitler, were introduced and had to be said before eating school meals.

Bernhard Rust wrote in Education in the Third Reich (1938): "The systematic reform of Germany's education system was started immediately after the coming into power of National Socialism. If these far-reaching changes were to materialize, teachers had first to be made capable of introducing them. Numerous courses, camps and working communities have been arranged to provide the necessary instruction, which includes the teaching of the philosophy of National Socialism in addition to the strictly educational subjects."

Richard Grunberger, the author of A Social History of the Third Reich (1971), has argued: "The profession's gradual loss of public esteem after 1933 was related to the anti-intellectual mood engendered by the Nazis' transformation of all traditional values. Teachers and priests tended to be the only members of village communities with educational qualifications above elementary or trade-school level - i.e. the only ones accustomed to conceptual thinking. Nazi egalitarianism - we think with our blood - encompassed a pseudo-revolution across a wide segment of rural society by inflating the self-esteem of villagers, while simultaneously lowering that of teachers."

One of the most important changes made by Bernhard Rust was the establishment of élite schools called Nationalpolitische Erziehungsanstalten (Napolas). Selection for entry included racial origins, physical fitness and membership of the Hitler Youth. These schools, run by the Schutzstaffel (SS), had the task of training the next generation of high-ranking people in the Nazi Party and the German Army. The syllabus was that of ordinary grammar schools with political inculcation in place of religious instruction and a tremendous emphasis on such sports as boxing, war games, rowing, sailing, gliding, shooting and riding motor-cycles. Only two out of the thirty-nine Napolas constructed over the next few years catered for girls.

After leaving school at the age of eighteen students joined the German Labour Service where they worked for the government for six months. Some young people then went on to university. Bernhard Rust claimed that the new education system would benefit the children of the working-class that made up 45 per cent of Germany's population. This promise was never fulfilled and after six years in office, only 3 per cent of university students came from working-class backgrounds. This was the same percentage as it was before Adolf Hitler came to power.

One of the major problems for schools in Nazi Germany was attendance. School authorities were instructed to grant pupils leave of absence to enable them to attend Hitler Youth courses. In one study of a school in Westphalia with 870 pupils showed that 23,000 school days were lost because of extra-mural activities during one academic year. This eventually had an impact on educational achievement. On 16th January, 1937, Colonel Hilpert of the German Army complained in Frankfurter Zeitung, that: "Our youth starts off with perfectly correct principles in the physical sphere of education, but frequently refuses to extend this to the mental sphere... Many of the candidates applying for commissions display a simply inconceivable lack of elementary knowledge."

By 1938 it was reported that there was a problem recruiting teachers. It was claimed that one teaching post in twelve was unfilled and Germany had 17,000 less teachers than it had before Adolf Hitler came to power. The main reason for this was the fall in teacher's pay. Entrants to the profession were offered a starting salary of 2,000 marks per annum. After deductions, this worked out at approximately 140 marks per month, or twenty marks more than was earned by the average lower-paid worker. The government tried to overcome this problem by introducing low-paid unqualified auxiliaries into schools.

Bernhard Rust also purged the universities of Jews and those with left-wing views. Over a thousand people lost their jobs including Albert Einstein, James Franck, Fritz Haber and Otto Meyerhof. Rust justified his actions by claiming that: "We must have a new Aryan generation at the universities, or else we will lose the future."

On this day in 1952 Elizabeth Robins died at 24 Montpelier Crescent, Brighton. Elizabeth Robins, the first child of Charles Ephraim Robins (1832–1893) and Hannah Maria Crow (1836–1901), was born in Louisville, Kentucky on 6th August, 1862. Elizabeth's mother, an opera singer, was committed to an insane asylum when she was a child. Her father was an insurance broker and banker. He was also a follower of Robert Owen and held progressive political views. Robins sent Elizabeth to Vassar College to study medicine but at eighteen she ran away to become an actress.

In 1885, Elizabeth Robins married the actor, George Richmond Parks. Whereas Elizabeth was in great demand, George struggled to get parts. On 31st May 1887, he wrote Elizabeth a note saying that "I will not stand in your light any longer" and signed it "Yours in death". That night he committed suicide by jumped into the Charles River wearing a suit of theatrical armour.

In 1888 Elizabeth travelled to London where she introduced British audiences to the work of Henrik Ibsen. Elizabeth produced and acted in several plays written by Ibsen including Hedda in Hedda Gabler, Rebecca West in Rosmersholm, Nora in A Doll's House and Hilda Wangel in The Master Builder. These plays were a great success and for the next few years Elizabeth Robins was one of the most popular actresses on the West End stage.

In 1898 Robins joined with her lover, William Archer, to form the New Century Theatre to sponsor non-profit productions of Ibsen. The company produced several plays including John Gabriel Borkman and Peer Gynt. After one production, the actress, Beatrice Patrick Campbell called her performance in "the most intellectually comprehensive piece of work I had seen on the English stage". According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "In the 1890s her incipient feminism had been fuelled by witnessing the exploitation of actresses by actor–managers and by Ibsen's depiction of strong-minded women."

1898 saw the publication of Robins' popular novel The Open Question. In 1900 Elizabeth travelled to Alaska in an attempt to find her brother, Raymond Robins, who had gone missing while on an expedition. Later she wrote about her experiences in Alaska in the novels, Magnetic North (1904) and Come and Find Me (1908).

Raymond returned to the United States and became an important figure in the social reform movement. He was a member of the Hull House settlement in Chicago and served on the national committee of the Progressive Party. In 1905 he married Margaret Dreier, who was later to become president of the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL).

Elizabeth was a strong feminist and initially had been a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. However, disillusioned by the organisation's lack of success, she joined the Women's Social and Political Union. Soon afterwards Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence commissioned Elizabeth to write a series of articles for her journal Votes for Women. She also asked her to write a play on the subject.

Evelyn Sharp saw Elizabeth Robins make a speech on women's suffrage in Tunbridge Wells in 1906: "The impression she made was profound, even on an audience predisposed to be hostile; and on me it was disastrous. From that moment I was not to know again for twelve years, if indeed ever again, what it meant to cease from mental strife; and I soon came to see with a horrible clarity why I had always hitherto shunned causes."

In 1908 two members of the Women's Social and Political Union, Bessie Hatton and Cicely Hamilton formed the Women Writers Suffrage League. Later that year the women formed the sister organisation, the Actresses' Franchise League. Elizabeth Robins became involved in both organisations. So also did the militant suffragette, Kitty Marion. Other actresses who joined included Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Vera Holme, Lena Ashwell, Christabel Marshall, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault.

Inez Bensusan oversaw the writing, collection and publication of Actresses' Franchise League plays. Pro-suffragette plays written by members of the Women Writers Suffrage League and performed by the AFL included the play Votes for Women by Elizabeth Robins and was performed by suffragists all over Britain. Robins also used the same story and characters for her novel The Convert. Both of these works of art deal with how men sexually exploit women. The heroine in the story, Vida Levering, a militant suffragette, rejects men because in the past, a lover, Geoffrey Stoner, a Conservative MP, forced her into having an abortion because he feared he would lose his inheritance. The heroine was initially named Christian Levering and was based on Elizabeth's close friend, Christabel Pankhurst. When Emmeline Pankhurst raised fears about what the play might do to Christabel's reputation, Elizabeth agreed to change the name to Vida. Elizabeth Robins, like her heroine in the play and novel, turned down offers of marriage from many men, including the playwright, George Bernard Shaw and the publisher William Heinemann.

In 1907 Elizabeth Robins became a committee member of the WSPU. In July 1909, she met Octavia Wilberforce. Octavia later recalled: "It was a turning point in my life… I had always read omnivorously and longed to write myself, and to meet so distinguished an author in the flesh was a terrific adventure. It was a small family luncheon at Phyllis Buxton's house. Elizabeth Robins was dressed in a blue suit, the colour of speedwell, which matched her beautiful deep-set eyes. I was introduced as Phyllis's friend who lives near Henfield... Elizabeth Robins.... with a charming grace and in an unforgettable voice asked me if I would come to tea one day and she would show me her modest little garden." The two women became lovers.

When the British government introduced the Cat and Mouse Act in 1913, Robins used her 15th century farmhouse at Backsettown, near Henfield, that she shared with Octavia Wilberforce, as a retreat for suffragettes recovering from hunger strike. It was also rumoured that the house was used as a hiding place for suffragettes on the run from the police.

Elizabeth wrote a large number of speeches defending militant suffragettes between 1906 and 1912 (a selection of these can by found her book Way Stations). However, Elizabeth herself never took part in these activities and so never experienced arrest or imprisonment. Emmeline Pankhurst told her it was more important that she remained free so that she could use her skills as a writer to support the suffragettes. It was also pointed out that as Elizabeth was not a British citizen she faced the possibility of being deported if she was arrested. Elizabeth once told a friend that she would "rather die than face prison."

Like many members of the WSPU, Elizabeth Robins objected to Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's dictatorial style of running the organisation. Elizabeth also disapproved of the decision in the summer of 1912 to start the arson campaign. When the Pankhursts refused to reconsider this decision, Robins resigned from the WSPU.

In 1908 Elizabeth became great friends with Octavia Wilberforce, a young woman who had a strong desire to become a doctor. When Octavia's father refused to pay for her studies, Elizabeth arranged to take over the financial responsibility for the course.

After women gained the vote, Robins took a growing interest in women's health care. Robins had been involved in raising funds for the Lady Chichester Hospital for Women & Children in Brighton since 1912. After the First World War Robins joined Louisa Martindale in her campaign for a much more ambitious project, a fifty-bed hospital run by women for women. Elizabeth persuaded many of her wealthy friends to give money and eventually the New Sussex Hospital for Women was opened in Brighton.

Elizabeth Robins also became involved in the campaign to allow women to enter the House of Lords. Elizabeth's friend, Margaret Haig, was the daughter of Lord Rhondda. He was a supporter of women's rights and in his will made arrangements for her to inherit his title. However, when he died in 1918, the Lords refused to allow Viscountess Rhondda to take her seat. Robins wrote numerous articles on the subject, but it was not until 1958, long after Viscountess Haig's death, that women were first admitted to the House of Lords.

Robins remained an active feminist throughout her life. In the 1920s she was a regular contributor to the feminist magazine, Time and Tide. Elizabeth also continued to write books such as Ancilla's Share: An Indictment of Sex Antagonism that explored the issues of sexual inequality.

Elizabeth Robins joined Octavia Wilberforce and Louisa Martindale in their campaign for a new fifty-bed, women's hospital in Brighton. After the New Sussex Hospital for Women in Brighton opened, Octavia became one of the three visiting doctors. Later she was appointed as the hospital's head physician.

In 1927 Octavia Wilberforce helped Elizabeth Robins and Marjorie Hubert set up a convalescent home at Backsettown, for overworked professional women. Wilberforce used the convalescent home as a means of exploring the best way of helping people to become fit and healthy. Patients were instructed not to talk about illness. Octavia believed diet was very important and patients were fed on locally produced fresh food. Whenever possible, patients were encouraged to eat their meals in the garden.

During the Second World War Elizabeth Robins went back to the United States. However, at the age of eighty-eight, she returned to live with Octavia Wilberforce at her home at 24 Montpelier Crescent in Brighton.

One of her regular visitors was Leonard Woolf. He recalled in his autobiography, The Journey Not the Arrival Matters (1969): "Elizabeth was, I think, devoted to Octavia, but she was also devoted to Elizabeth Robins; when we first knew her, she was already a elderly woman and a dedicated egoist, but she was still a fascinating as well as an exasperating egoist. When young she must have been beautiful, very vivacious, a gleam of genius with that indescribably female charm which made her invincible to all men and most women. One felt all this still lingering in her as one sometimes feels the beauty of summer still lingering in an autumn garden. After the war, when she returned from Florida to Brighton, a very old frail woman, she used every so often to ask me to come and see her in bed, surrounded by boxes full of letters, cuttings, memoranda, and snippets of every sort and kind. In stamina I am myself inclined to be invincible, indefatigable, and imperishable, and I was nearly twenty years younger than Elizabeth, but after two or three hours' conversation with her in Montpelier Crescent, I have often staggered out of the house shaky, drained, and debilitated as if I had just recovered from a severe attack on influenza."

On this day in 1955 Stella Browne, died following a heart attack at her home, 39 Hawarden Avenue, Sefton Park, Liverpool.

Stella Browne, the daughter of Daniel Marshall Browne, was born at Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on 9th May 1880. Her father drowned on duty with the Canadian Marine in 1883.

Browne was educated at Saint Felix School in Southwold and Somerville College. After achieving a second-class honours in modern history at the University of Oxford in 1902, she became a schoolteacher. Later she worked under Mary Sheepshanks at Morley College for Working Men and Women. She was also a member of the Women Social & Political Union.

On 23rd November, 1911, Dora Marsden, Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe published the first edition of The Freewoman. The journal caused a storm when it advocated free love and encouraged women not to get married. The journal also included articles that suggested communal childcare and co-operative housekeeping. Stella Browne became one of the journal's most important contributors.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

On 21st March 1912 Stella Browne wrote about her views on free-love in The Freewoman: "The sexual experience is the right of every human being not hopelessly afflicted in mind or body and should be entirely a matter of free choice and personal preference untainted by bargain or compulsion."

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Stella Browne was an active member of the Freewoman Discussion Circles. Talks included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Grace Jardine, Harriet Shaw Weaver, Edmund Haynes, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Rebecca West, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

In 1913 Stella Browne, joined forces with George Ives, Edward Carpenter, Magnus Hirschfeld and Laurence Housman to establish the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology. The papers she gave to the society, included "The sexual variety and variability among women and their bearing upon social reconstruction" (1915).

Browne wrote in 1917: "The psychology of homogenic women has been much less studied than that of inverted men. Probably there are many varieties and subtleties of emotional fibre among them. Some very great authorities have believed that the inverted woman is more often bisexual - less exclusively attracted to offer women - than the inverted man. This view needs very careful confirmation, but if true, it would prove the greater plasticity of women's sex-impulse. It has also been stated that the invert, man or woman, is drawn towards the normal types of their own sex... Certainly, the heterosexual woman of passionate but shy and sensitive nature, is often responsive to the inverted woman's advances, especially if she is erotically ignorant and inexperienced. Also many women of quite normally directed (heterosexual) inclinations, realise in mature life, when they have experienced passion, that the devoted admiration and friendship they felt for certain girl friends, had a real, though perfectly unconscious spark of desire in its exaltation and intensity; an unmistakable, indefinable note, which was absolutely lacking in many equally sincere and lasting friendships."

Stella Browne published Studies in Female Inversion in 1918: "This problem of feminine inversion is very pressing and immediate, taking into consideration the fact that in the near future, for at least a generation, the circumstances of women's lives and work will tend, even more than at present, to favor the frigid (sexually repressed) and next to the frigid, the inverted types. Even at present, the social and affectional side of the invert's nature has often fuller opportunity of satisfaction than the heterosexual woman's, but often at the cost of adequate and definite physical expression. I think it is perhaps not wholly uncalled-for, to underline very strongly my opinion that the homosexual impulse is not in any way superior to the normal; it has a fully equal right to existence and expression, it is no worse, no lower; but no better."

According to her biographer, Lesley A. Hall: "Browne emphasized the need for women to speak about their own experiences. In both principle and practice Stella was a convinced believer in free love, known to have had various lovers, certainly some male, and possibly some female, though these cannot be reliably identified."

Browne, a member of the Malthusian League, campaigned strongly for birth control and abortion. She was also a member of the Divorce Law Reform Union, the No-Conscription Fellowship, the Humanitarian League, the Fabian Society, the Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain.