Spartacus Blog

The Delusions of Neville Chamberlain and Theresa May

Over the last few weeks I have been writing about the British foreign policy crisis of 1938. This has included reading the Cabinet minutes, the letters and diaries of government ministers and senior civil servants and the memoirs of the leading figures in this political drama. What strikes me is the similarities between the situation faced by Neville Chamberlain in 1938 and Theresa May today. I am not suggesting that May is attempting to appease the EU, in fact, the opposite is the case. My point concerns the relationship between the Prime Minister and the Cabinet. Chamberlain's ministers considered him delusional. I would not be surprised if May's ministers felt the same way about Theresa May. In 1938 it was very difficult at the time to know how Chamberlain had little support for his policy of appeasing Adolf Hitler in his Cabinet. However, like May, Chamberlain avoided taking votes in Cabinet, and threatened he would call a General Election if they resigned and voted against him in Parliament.

The first time the government was accused of appeasing fascism was when Clement Attlee, who had just replaced the pacifist, George Lansbury, as leader of the Labour Party. It came when Adolf Hitler sent German troops into the Rhineland. The German generals were very much against the plan, claiming that the French Army would win a victory in the military conflict that was bound to follow this action. Hitler ignored their advice and on 1st March, 1936, three German battalions marched into the Rhineland. Hitler later admitted: "The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance." (1)

Conservative Government and Appeasement

The British government accepted Hitler's Rhineland coup. Sir Anthony Eden, the new foreign secretary, informed the French that the British government was not prepared to support military action. The chiefs of staff felt Britain was in no position to go to war with Germany over the issue. The Rhineland invasion was not seen by the British government as an act of unprovoked aggression but as the righting of an injustice left behind by the Treaty of Versailles. Eden apparently said that he would not oppose the move because "Hitler was only going into his own back garden." (2)

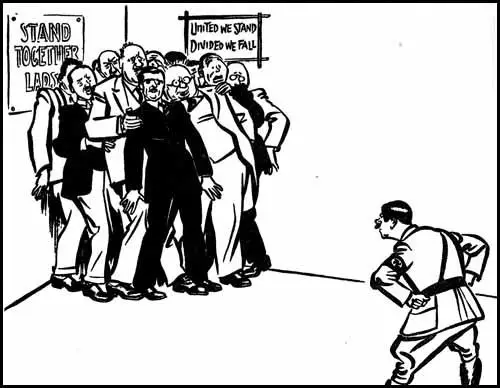

Attlee attacked the Conservative government for the acceptance that Hitler was allowed to march into the Rhineland without any measures taken against Germany. He spoke of the dangers of accepting Hitler's actions as merely righting one of the punitive wrongs of Versailles. "In the last five years we have had quite enough of dodging difficulties, of using forms of words to avoid facing up to realities... I am afraid that you may get a patched-up peace and then another crisis next year." (3)

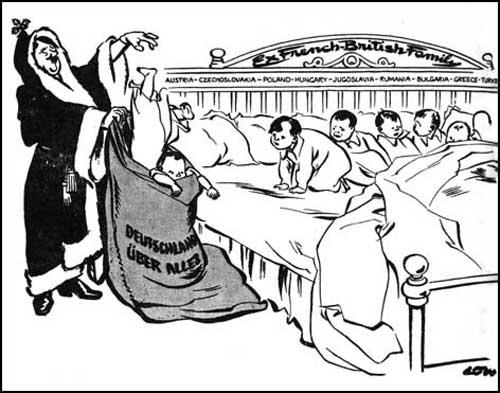

say, twenty-five years?", Evening Standard (12th March, 1936)

Attlee repeated the charge during a debate on the Spanish Civil War. In the 1930s the Conservative Party feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government. On the 19th July, 1936, Spain's prime minister, José Giral, sent a request to Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, for aircraft and armaments. The following day the French government decided to help and on 22nd July agreed to send 20 bombers and other arms. This news was criticized by the right-wing press and the non-socialist members of the government began to argue against the aid and therefore Blum decided to see what his British allies were going to do. (4)

Anthony Eden received advice that "apart from foreign intervention, the sides were so evenly balanced that neither could win." Eden warned Blum that he believed that if the French government helped the Spanish government it would only encourage Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to aid the Nationalists. Edouard Daladier, the French war minister, was also aware that French armaments were inferior to those that General Francisco Franco could obtain from the dictators. Eden later recalled: "The French government acted most loyally by us." On 8th August the French cabinet suspended all further arms sales, and four days later it was decided to form an international committee of control "to supervise the agreement and consider further action." (5)

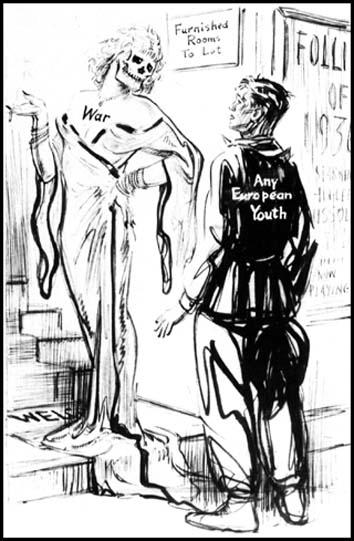

you right. I used to know your Daddy,

New York Daily News (25th April, 1936)

In a speech in October, 1936, Clement Attlee described the Spanish Civil War as "a fight for the soul of Europe", charging that non-intervention had become "a farce". He added that the government was guilty of incremental steps of appeasement. If Britain had stood firm against Mussolini over Abyssinia, there would not have been this trouble in Spain. He argued there had been "no policy in foreign affairs except the policy of giving way. The result of that is a world in anarchy." The government's policy "has not brought us nearer peace but has brought us closer and closer to the danger of war." (6)

Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler

On 28th May, 1937, Stanley Baldwin resigned and was replaced by Neville Chamberlain. Whereas Baldwin and Eden had allowed themselves to drift into a policy into a policy of appeasement. Chamberlain believed it was a rational policy and was determined to surround himself with other appeasers. A few weeks before he officially became prime minister, Chamberlain arranged for Nevile Henderson to replace Eric Phipps as British ambassador to Berlin. Phipps had been warning of the dangers of Hitler and in his reports he gave ample and frequent warning of Nazi intentions to his superiors in London. He argued that Germany could only be contained "through accelerated and extensive British rearmament". (7) Chamberlain urged Henderson to "take the line of co-operation with Germany". (8)

Henderson later recalled that Chamberlain "outlined to me his views on general policy towards Germany, and I think I may honestly say that to the last and bitter end I followed the general line which he set me." (9) There was some concern in the Foreign Office about the appointment of Henderson as some saw him as a political extremist and a supporter of Hitler. Oliver Harvey wrote in his diary: "I hope we are not sending another Ribbentrop to Berlin." (10)

Before leaving for Nazi Germany, Henderson read a copy of Hitler's Mein Kampf. "Though it was in parts turgid and prolix and would have been more readable if it had been condensed to a third of its length, it struck me at the time as a remarkable production on the part of a man whose education and political experience appeared to have been as slight, on his own showing, as Herr Hitler's." (11)

On 1st June, 1937, Henderson attended a banquet arranged by the German-English Society of Berlin. A large number of leading Nazis were in attendance when he made a speech where he defended Adolf Hitler and urged the British people to "lay less stress on Nazi dictatorship and much more emphasis on the great social experiment which is being tried out in this country." (12)

This speech provoked an uproar and some left-wing journalists described him as "our Nazi ambassador at Berlin". However, some newspaper editors, including Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, supported this approach to Nazi Germany. In the House of Commons the Conservative Party MP, Alfred Knox offered congratulations "to HM Ambassador in Berlin on having made a real contribution to the cause of peace". (13) Richard Griffiths, the author of Fellow Travellers of the Right (1979), has pointed out that "Henderson was not just an eccentric individual, as has been suggested; he stands as an example of a whole trend in British thought at the time." (14)

Some senior figures at MI5 were very opposed to appeasement and supplied Neville Chamberlain with a document from a spy close to Hitler quoting him as saying: "If I were Chamberlain I would not delay for a minute to prepare my country in the most drastic way for a total war... It is astounding how easy the democracies make it for us to reach our goal....If the information which has proved generally reliable and accurate in the past is to be believed, Germany is at the beginning of a Napoleonic era and her rulers contemplate a great expansion of German power." (15)

German Spies and the Conservative Government

The appointment of Henderson raised concerns in the Foreign Office. Sir Robert Vansittart, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, who condemned Henderson's speeches and the letters he was sending back to London. These were "acts of folly and completely improper... In 35 years' experience I cannot recall such a series of incidents created by an Ambassador." (16) Eden later recalled that it was "an international misfortune that we should have been represented in Berlin at this time by a man who, so far from warning the Nazis, was constantly making excuses for them, often in their company." (17)

The behaviour of Chamberlain and Henderson was also concerning the intelligence services. They had been closely monitoring the actions of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador to London. His main objective was to persuade the British government not to get involved in Germany territorial disputes and to work together against the the communist government in the Soviet Union. During this period Von Ribbentrop told Hitler that the British "were so lethargic and paralyzed that they would accept without complaint any aggressive moves by Nazi Germany." (18)

According to Christopher Andrew, the author of Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5 (2010) MI5 was receiving information from a diplomat by the name of Wolfgang zu Putlitz, who was working in the German Embassy. Putlitz told MI5 that "He (Ribbentrop) regarded Mr Chamberlain as pro-German and said he would be his own Foreign Minister. While he would not dismiss Mr Eden he would deprive him of his influence at the Foreign Office. Mr Eden was regarded as an enemy of Germany." Putlitz constantly provided clear warnings that negotiations with Hitler and Rippentrop were likely to be fruitless and the only way to deal with Nazi Germany was to stand firm. Putlitz told MI5 that her policy of appeasement was "letting the trump cards fall out of her hands. If she had adopted, or even now adopted, a firm attitude and threatened war, Hitler would not succeed in this kind of bluff". (19)

Lord Halifax, the leader of the House of Lords, shared Chamberlain's belief in appeasement. In 1936 Halifax visited Nazi Germany for the first time. Halifax's friend, Henry (Chips) Channon, reported that: "I had a long conversation with Lord Halifax about Germany and his recent visit. He described Hitler's appearance, his khaki shirt, black breeches and patent leather evening shoes. He told me he liked all the Nazi leaders, even Goebbels, and he was much impressed, interested and amused by the visit. He thinks the regime absolutely fantastic, perhaps even too fantastic to be taken seriously. But he is very glad that he went, and thinks good may come of it. I was riveted by all he said, and reluctant to let him go." (20)

Halifax later explained in his autobiography, Fullness of Days (1957): "The advent of Hitler to power in 1933 had coincided with a high tide of wholly irrational pacifist sentiment in Britain, which caused profound damage both at home and abroad. At home it immensely aggravated the difficulty, great in any case as it was bound to be, of bringing the British people to appreciate and face up to the new situation which Hitler was creating; abroad it doubtless served to tempt him and others to suppose that in shaping their policies this country need not be too seriously regarded." (21)

Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary, supported Chamberlain's appeasement policy because he believed that Britain needed time to rearm. However, as Keith Middlemas, the author of Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972), has pointed out: "While Eden held to the policy of keeping Germany guessing long enough to give Britain time to rearm, so that he could negotiate from a position of strength, Chamberlain, conscious of time running out, preferred to settle the outstanding accounts at once." (22)

Nevile Henderson upset Eden and Sir Robert Vansittart, his boss at the Foreign Office, by attending the annual Nuremberg Rally. (23) Henderson told Eden that he was regarded as "too pro-Nazi or pro-German". However, he believed that sometimes it was necessary to impose a dictatorship. He considered Antonio Salazar, "the present dictator of Portugal" one of the "wisest statesmen which the post-war period has produced in Europe". He argued that Hitler had probably gone too far with the Nuremberg Laws but "dictatorships are not always evil and, however anathema the principle may be to us, it is unfair to condemn a whole country, or even a whole system. because parts of it are bad." (24)

In November, 1937, Neville Chamberlain announced he was sending his friend, and fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, to meet Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring in Germany. Anthony Eden was furious when he discovered this and felt he was being undermined as foreign secretary. One historian has commented: "Eden and Chamberlain seemed like two horses harnessed to a cart, both pulling in different directions." (25)

In his diary, Halifax records how he told Hitler: "Although there was much in the Nazi system that profoundly offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) had done for Germany, and to the achievement from his point of view of keeping Communism out of his country." This was a reference to the fact that Hitler had banned the Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in Germany and placed its leaders in Concentration Camps. Halifax told Hitler: "On all these matters (Danzig, Austria, Czechoslovakia) ... the British government... "were not necessarily concerned to stand for the status quo as today... If reasonable settlements could be reached with... those primarily concerned we certainly had no desire to block." (26)

Czechoslovakia

In 1937 Hitler began making demands over Czechoslovakia, a country that had been created after the allied victory in the First World War. Before the conflict it had been part of the Austrian-Hungarian empire. The population consisted of Czechs (51%), Slovaks (16%), Germans (22%), Hungarians (5%) and Rusyns (4%). Eden made it clear to Chamberlain that he was unwilling to force President Eduard Beneš to make concessions. William Strang, a senior figure in the Foreign Office, also urged caution over these negotiations: "Even if it were in our interest to strike a bargain with Germany, it would in present circumstances be impossible to do so. Public sentiment here and our existing international obligations are all against it." (27)

At a Cabinet meeting Chamberlain made it clear that he favoured making concessions to Hitler. Eden found this unacceptable and resigned on 20th February 1938. He told the House of Commons the following day: "I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that temper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world." (28)

Chamberlain now appointed fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, as his new foreign secretary. Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador in Berlin, told Chamberlain that we would lose a war with Nazi Germany. Halifax recommended that the British government should apply pressure on President Eduard Beneš to give up the Sudetenland, with its largely German-speaking population, to Germany. Henderson's biographer, Peter Neville, pointed out: "So strong was this conviction that he sometimes erred on the side of prejudice against the Czechs and their president, Beneš". (29)

It was decided to mount a smear campaign against opponents of appeasement within and outside the Conservative Party. Chamberlain employed Sir Joseph Ball, a former member of MI5, to gather information on the contacts and financial arrangements of his political opponents, and even to intercept their telephone calls. (30) Stanley Baldwin complained to Anthony Eden that his own work "in keeping politics national instead of party" had been rendered worthless. Eden replied that Chamberlain was attempting to "return to class warfare in its bitterest form". (31)

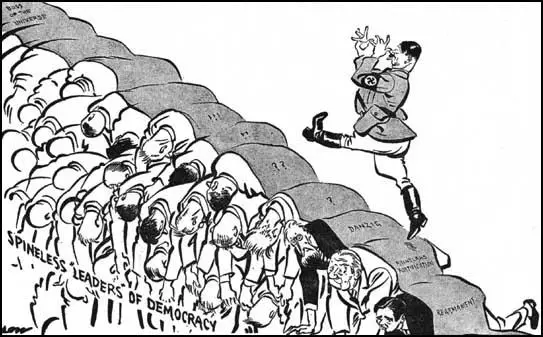

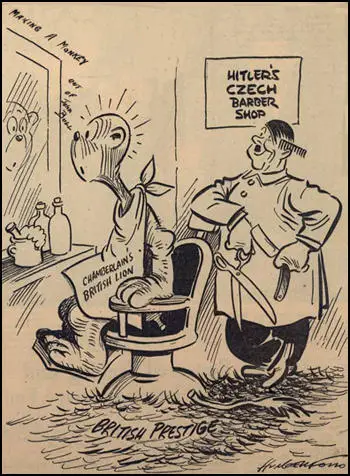

Chicago Times (8th September, 1938)

In March 1938, Adolf Hitler advised Konrad Henlein, the leader of the Sudeten Germans, on his political campaign. Hitler told him "that demands should be made by the Sudeten German Party which are unacceptable to the Czech government." Henlein later summarised the comments: "We must always demand so much that we can never be satisfied." Hitler suggested that once a crisis was established, he would be willing to send German troops into Czechoslovakia. (32)

The Czech crisis reached the first of many dangerous points in May 1938. It was reported that two Sudeten German motorcyclists had been shot dead by the Czech police. This led to rumours of Hitler preparing to use the incident as a pretext for invasion and there were reports of German troops assembling near the Czech border. The French and Soviet governments pledged support to the Czechs. Lord Halifax sent a message to Berlin which warned that if force was used Germany "could not count upon this country being able to stand aside". At the same time he sent a diplomatic message which told the French they should not assume Britain would fight to save Czechoslovakia. (33)

On 12th September, 1938, Hitler whipped his supporters into a frenzy at the annual Nuremberg Rally by claiming the Sudeten Germans were "not alone" and would be protected by Nazi Germany. A series of demonstrations took place in the Sudeten area and on 13th September, the Czech government decided to introduce martial law in the area. Konrad Henlein, the leader of the Sudeten Germans, fled to Germany for protection. (34)

Chamberlain now sent Hitler a message requesting an immediate meeting, which was promptly granted. Hitler invited Chamberlain to see him at his home in Berchtesgaden. It would be the first visit by a British prime minister to Germany for over 60 years. The last leader to visit the country was Benjamin Disraeli when he attended the Congress of Berlin in 1878. Members of the Czech government were horrified when they heard the news as they feared Chamberlain would accept Hitler's demands for the transfer of the Sudetenland to Germany. (35)

On 15th September, 1938, Chamberlain, aged sixty-nine, boarded a Lockheed Electra aircraft for a seven-hour journey to Munich, followed by a three-hour car ride up the long and winding roads to Berchtesgaden. The first meeting lasted for three hours. Hitler made it very clear that he intended to "stop the suffering" of the Sudeten Germans by force. Chamberlain asked Hitler what was required for a peaceful solution. Hitler demanded the transfer of all districts in Czechoslovakia with a 50 per cent or more German-speaking population. Chamberlain said he had nothing against the idea in principle, but would need to overcome "practical difficulties". (36)

Hitler flattered Chamberlain and this had the desired impact on him. He told his sister: "Horace Wilson heard from various people who were with Hitler after my interview that he had been very favourably impressed. I have had a conversation with a man, he said, and one with whom I can do business and he liked the rapidity with which I had grasped the essentials. In short I had established a certain confidence, which was my aim, and in spite of the hardness and ruthlessness I thought I saw in his face I got the impression that here was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word." (37)

Threatened Cabinet Rebellion

Chamberlain called an emergency cabinet meeting on 17th September. Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, recorded in his diary: "Looking back upon what he said, the curious thing seems to me now to have been that he recounted his experiences with some satisfaction. Although he said that at first sight Hitler struck him as 'the commonest little dog' he had ever seen, without one sign of distinction, nevertheless he was obviously pleased at the reports he had subsequently received of the good impression that he himself had made. He told us with obvious satisfaction how Hitler had said to someone that he had felt that he, Chamberlain, was 'a man.' But the bare facts of the interview were frightful. None of the elaborate schemes which had been so carefully worked out, and which the Prime Minister had intended to put forward, had ever been mentioned. He had felt that the atmosphere did not allow of them. After ranting and raving at him, Hitler had talked about self-determination and asked the Prime Minister whether he accepted the principle. The Prime Minister had replied that he must consult his colleagues. From beginning to end Hitler had not shown the slightest sign of yielding on a single point. The Prime Minister seemed to expect us all to accept that principle without further discussion because the time was getting on." (38)

Chamberlain told the cabinet that he was convinced "that Herr Hitler was telling the truth". Thomas Inskip, Minister for Coordination of Defence, and a loyal supporter of Chamberlain, felt uneasy by the prime minister's performance. He recorded in his diary: "The impression made by the P.M.'s story was a little painful. It was plain that Hitler had made all the running: he had in fact blackmailed the P.M." (39)

Oliver Stanley, President of the Board of Trade objected vigorously to Hitler's "ultimatum", and declared that "if the choice for the Government in the next four days is between surrender and fighting, we ought to fight". Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, Lord Privy Seal, said he was "prepared to face war in order to free the world from the continual threat of ultimatums". Douglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham, attempted to rally the cabinet to Chamberlain's cause with the defeatist statement that he thought that we "had no alternative but to submit to humiliation." (40)

Duff Cooper wrote in his diary: "I argued that the main interest of this country had always been to prevent any one Power from obtaining undue predominance in Europe; but we were now faced with probably the most formidable Power that had ever dominated Europe, and resistance to that Power was quite obviously a British interest. If I thought surrender would bring lasting peace I should be in favour of surrender, but I did not believe there would ever be peace in Europe so long as Nazism ruled in Germany. The next act of aggression might be one that it would be far harder for us to resist. Supposing it was an attack on one of our Colonies. We shouldn't have a friend in Europe to assist us, nor even the sympathy of the United States which we had today. We certainly shouldn't catch up the Germans in rearmament. On the contrary, they would increase their lead. However, despite all the arguments in favour of taking a strong stand now, which would almost certainly lead to war, I was so impressed by the fearful responsibility of incurring a war that might possibly be avoided, that I thought it worth while to postpone it in the very faint hope that some internal event might bring about the fall of the Nazi regime. But there were limits to the humiliation I was prepared to accept." (41)

Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, was the most vociferous in voicing his concerns, principally on the strategic grounds that Czechoslovakia could not be defended. Once the Sudeten German areas had been transferred, it would become "an unstable State economically, would be strategically unsound, and there was no means by which we could implement the guarantee. It was difficult to see how it could survive." Hore-Belisha argued the proposals offered nothing more than "a postponement of the evil day." According to Thomas Inskip, Hore-Belisha got into an acrimonious discussion with a "tired and dispirited" Chamberlain. (42)

Chamberlain ignored his critics and without taking a vote he insisted the Cabinet had "accepted the principle of self-determination and given him the support he had asked for". Chamberlain claimed that his policy was very popular with the public and that he would love to show his colleagues "some of the many letters which he had received in the last few days, which showed the intense feeling of relief throughout the country, and of thankfulness and gratitude for the load which had been lifted, at least temporarily." (43) He told his sister, Ida Chamberlain, that he had "finally overcome all critics, some of whom had been concerting opposition beforehand." (44)

When the governments of Czechoslovakia and France rejected Chamberlain's deal, instead of accepting defeat, he returned to Hitler to see if he could get some concessions. Chamberlain could only get away with this is that he had the support of the vast majority of newspapers, who were loyal supporters of the Conservative Party. This was a more important factor in the 1930s than today when we have social media to provide more balance in reporting the news.

Samuel Hoare, the Home Secretary, was given the task of persuading the newspapers to support Chamberlain's plan. He began to hold daily meetings with proprietors and editors. One of the key figures he approached was Sir Walter Layton, the chairman of the News Chronicle. Layton agreed to help and when one of his young journalists returned from Prague with a secret document which revealed the detailed timetable for the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, he arranged for the story to be suppressed. Vernon Bartlett had his articles censored and when the newspaper editor, Gerald Barry, wrote an anti-Chamberlain leader, Layton sacked him. (45)

Sir Horace Wilson, a senior civil servant who worked closely with Chamberlain, was given the task of controlling the way appeasement was reported on the BBC. A subsequent internal BBC report on the meetings between Hitler and Chamberlain in 1938, revealed that "towards the end of August, when the international situation was daily growing more critical", Wilson made a number of veiled threats. The report also confirmed that "news bulletins as a whole inevitably fell into line with Government policy at this critical juncture." (46)

Paramount News released a newsreel featuring interviews with two senior British journalists who were critical of Chamberlain. British cinema audiences greeted "with considerable applause" the warning that "Germany is marching to a diplomatic triumph... Our people have not been told the truth." Conservative Central Office complained and Lord Halifax approached Joseph Kennedy, the American ambassador based in London, and asked for the offending interviews to be removed. Kennedy brought his influence to bear on Paramount's American holding company, and the offending newsreel was quickly withdrawn. (47)

Despite this massive propaganda campaign, the general public was not convinced about the policy of appeasement. A Mass Observation poll found that 44 per cent of those questioned expressed themselves to be "indignant" at Chamberlain's policy, while only 18 per cent were supportive. Of those men who were questioned, 67 per cent said they were willing to fight to defend Czechoslovakia. On the day that he returned to London, a crowd of over 10,000 people massed in Whitehall, shouting "Stand by the Czechs!" and "Chamberlain must go!" (48)

Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreign minister, told the assembly of the United Nations that the Soviet Union intended to fulfil its obligations towards Czechoslovakia, if France would do the same. (49) This created a serious problem for the Anglo-French plan and Chamberlain announced that he was going to have another meeting with Hitler. Chamberlain arrived in Godesberg on 22nd September. At their first meeting Hitler made a series of new demands. He now wanted the immediate occupation of Sudeten areas and non-German-speakers who wished to leave would be allowed to take only a single suitcase of belongings with them. He also added certain areas with less than 50 per cent German speakers and raised Polish and Hungarian grievances in other areas of Czechoslovakia. (50)

At another meeting the following day Chamberlain pleaded with him to return to the terms of the previous agreement. Chamberlain pointed out that he had already risked his entire political reputation to gain the Anglo-French plan and if he marched into the Sudetenland, his political career would be destroyed. He pointed out that when he left England he had been booed by the crowd at the airport. Hitler refused to budge and restated that he would occupy the Sudeten areas on 1st October. Chamberlain decided to break-off talks and return to London. (51)

Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, felt that it would be impossible for the Cabinet to support Chamberlain in his efforts to do a deal with Hitler. When he read Hitler's latest memorandum which laid out his demands he thought Chamberlain would advise the Cabinet to reject it. He was shocked when he discovered that Chamberlain wanted to accept these terms. "I was completely horrified. He was quite calmly for total surrender... Hitler has evidently hypnotised him to a point." (52)

On 24th September the Cabinet had a full-day meeting. Chamberlain told his ministers that he was "satisfied Herr Hitler would not go back on his word" and was not using the crisis as an excuse to "crush Czechoslovakia or dominate Europe." According to the Cabinet minutes: "In his view Herr Hitler had certain standards; he would not deliberately deceive a man whom he respected, and he was sure that Herr Hitler now felt some respect for him... He thought that he had now established an influence over Herr Hitler, and the latter trusted him. The Prime Minister believed that Herr Hitler was speaking the truth." (53)

Chamberlain had now lost the support of most of his Cabinet. Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, rejected Hitler's proposal, and called for the army to be mobilised. It was, he contended, "the only argument Hitler would understand". He then warned that the Cabinet "would never be forgiven if there were a sudden attack on us and we had failed to take the proper steps." Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, Walter Elliot, Oliver Stanley, Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton, all spoke against Hitler's proposals. (54)

Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, was the most critical of Hitler's proposals. He was always concerned that the government would achieve "peace with dishonour", now he feared "war with dishonour". Cooper pointed out the chiefs of staff had already called for mobilisation - "we might some day have to explain why we had disregarded their advice." Chamberlain responded angrily that the advice had only been given on the assumption that war was imminent. Cooper commented that it was "difficult to deny that any such danger existed". In his diary that night Cooper wrote: "Hitler has cast a spell over Neville". (55)

Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, the great supporter of appeasement, was now having doubts about the policy. He wrote to Chamberlain explaining: "It may help you if we give you some indication of what seems predominant public opinion as expressed in press and elsewhere. While mistrustful of our plan but prepared perhaps to accept it with reluctance as alternative to war, great mass of public opinion seems to be hardening in sense of feeling that we have gone to limit of concession and that it is up to Chancellor Hitler to make some contribution." (56)

Earl Winterton went to see Leo Amery, one of Chamberlain's oldest friends, and someone who was felt to have influence over the prime minister. He admitted that "at least four of five Cabinet members were seriously contemplating resignation." (57) Amery, who was against the deal wrote to Lord Halifax: "Almost everyone I have met, has been appalled by the so-called peace we have forced upon the Czechs." (58)

Amery also wrote a letter to Chamberlain, which he delivered himself. How, he asked, could Chamberlain expect the Czechs "to commit such an act of folly and cowardice?" If he failed to stand up to Hitler, he risked making Britain look "ridiculous as well as contemptible in the eyes of the world". Amery concluded the letter with the words: "If the country and the House should once suppose that you were prepared to acquiesce in or even endorse this latest demand, there would be a tremendous feeling of revulsion against you." (59)

However, ministers, although they knew Chamberlain was making war with Germany more likely by his policy of appeasement, refused to resign and bring down the government, because they thought it would ruin their political careers. This is the same dilemma facing Tory ministers such as Amber Rudd, David Gauke, Greg Clark, Philip Hammond, Richard Harrington, Claire Perry, Margot James and Tobias Ellwood. These people face the additional problem of facing deselection if they do not implement Brexit.

The only government minister to resign over Czechoslovakia was Duff Cooper, the First Lord of the Admiralty. Unfortunately, he only resigned after the signing of the Munich Agreement when it was too late to stop Hitler. Maybe those ministers should take time to read Cooper's resignation speech that he made in the House of Commons. It included the following words: "The Prime Minister may be right. I can assure you, Mr. Speaker, with the deepest sincerity, that I hope and pray that he is right, but I cannot believe what he believes. I wish I could. Therefore, I can be of no assistance to him in his Government. I should be only a hindrance, and it is much better that I should go. I remember when we were discussing the Godesberg ultimatum that I said that if I were a party to persuading, or even to suggesting to, the Czechoslovak Government that they should accept that ultimatum, I should never be able to hold up my head again. I have forfeited a great deal. I have given up an office that I loved, work in which I was deeply interested and a staff of which any man might be proud. I have given up associations in that work with my colleagues with whom I have maintained for many years the most harmonious relations, not only as colleagues but as friends. I have given up the privilege of serving as lieutenant to a leader whom I still regard with the deepest admiration and affection. I have ruined, perhaps, my political career. But that is a little matter; I have retained something which is to me of great value - I can still walk about the world with my head erect." (60)

Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, made the most significant attack on the Munich Agreement. "We have felt that we are in the midst of a tragedy. We have felt humiliation. This has not been a victory for reason and humanity. It has been a victory for brute force. At every stage of the proceedings there have been time limits laid down by the owner and ruler of armed force. The terms have not been terms negotiated; they have been terms laid down as ultimata. We have seen today a gallant, civilized and democratic people betrayed and handed over to a ruthless despotism. We have seen something more. We have seen the cause of democracy, which is, in our view, the cause of civilization and humanity, receive a terrible defeat.... The events of these last few days constitute one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained. There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition. He has opened his way to the food, the oil and the resources which he requires in order to consolidate his military power, and he has successfully defeated and reduced to impotence the forces that might have stood against the rule of violence." (61)

Other Conservative MPs emboldened by Cooper's speech, such as Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden, Leo Amery, Harold Macmillan, Harold Nicolson, Louis Spears, Robert Boothby, Brendan Bracken, Victor Cazalet, Sidney Herbert, Duncan Sandys, Leonard Ropner, Ronald Cartland, Ronald Tree, Paul Emrys-Evans, Vyvyan Adams and Jack Macnamara, now spoke out against appeasement. However, not one of them voted against the Munich Agreement at the end of the debate. The main reason why 20 Conservative MPs abstained rather than voting with the Labour Party was that Chamberlain threatened a general election if his motion was defeated. (62)

British Public and Appeasement

They were probably right to fear a general election. Despite the large cheering crowds that Chamberlain saw after the signing of the Munich Agreement and the overwhelming support he received from the BBC and the national press, the people felt uneasy about what had taken place. The overwhelming sensation for many people, as expressed by the philosopher, Sir Isaiah Berlin, was a combination of "shame and relief". (63)

In all the eight by-elections that followed the Munich Agreement, the Conservative Party suffered a fall in its support. This included the defeat of the Conservative candidate at Bridgwater. The left-wing journalist, Vernon Bartlett, whose critical reports on Chamberlain's foreign policy had been censored by his newspaper, the News Chronicle, stood as an anti-appeasement candidate. Bartlett won the seat with 6,000 more votes than the combined Labour and Liberal votes at the previous election, turning an overall Conservative lead of 4,500 votes into a deficit of over 2,000. Henry Channon, the Tory MP, noted in his diary: "I am dumbfounded by the news of the Bridgewater election, where Vernon Bartlett, standing as an Independent, has had a great victory over the Government candidate. This is the worst blow the Government has had since 1935." (64)

Sir George Joseph Ball, Director of the Conservative Research Department, the man who had been trying to persuade Chamberlain to hold a snap General Election after the signing of the Munich Agreement told him at the end of November, 1938: "The outlook is far less promising than it was a few months ago, and there are a large number of seats held by only small majorities, so that only a small turnover of votes would defeat the Government." Ball advised the election should be postponed. (65)

Alliance with the Soviet Union

By the summer of 1939 the public had completely rejected Chamberlain's appeasement policy. Instead they favoured what Clement Attlee had been demanding for 18 months, a military alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. In June, 1939, a public opinion poll showed that 84 per cent of the British public favoured an Anglo-French-Soviet military alliance. Negotiations progressed very slowly and it has been claimed by Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998), that "Chamberlain did not seem to care less whether an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed at all, kept placing obstructions in the way of concluding an agreement swiftly." (66)

After the successful invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hitler began to make demands on the Polish government. This included a request for the return of the free city of Danzig and the amendment of the Polish corridor. Not surprisingly, Poland called on the British government for help. On 24th April, 1939, Colonel Józef Beck, the Polish foreign minister, arrived in London and proposed a secret understanding involving Britain, France and Poland. Chamberlain welcomed the suggestion as he wanted to pursue a policy of deterrence, without extreme provocation." (67)

The guarantee to Poland, which France joined, was officially announced on 31st March, 1939. David Lloyd George, immediately objected to the agreement. As he pointed out: "If war occurred tomorrow, you could not send a single battalion to Poland." (68) Chamberlain responded that he believed the guarantee would point "not towards war, which wins nothing or settles nothing, cures nothing, ends nothing" but would open the way towards "a more wholesome era, when reason will take place of force." (69)

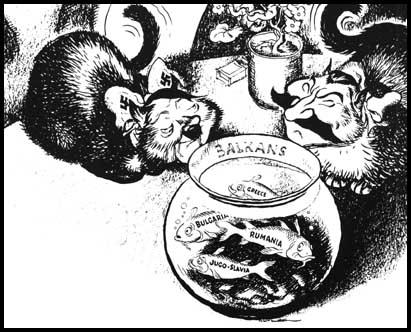

On 13th April, further Anglo-French guarantees were offered to Rumania, Greece and Turkey. The following week the government introduced conscription for all males aged twenty and twenty-one. It also announced that spending limits on the army, navy and air force were abandoned and a ministry of supply to co-ordinate the supply of war materials was established. Hitler and Mussolini responded by signing a military alliance - the Pact of Steel - which added further to the idea of an inevitable war. (70)

The chiefs of staff supported the idea of an Anglo-Soviet alliance. On 16th May, Ernle Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, Minister for Coordination of Defence, strongly urged the conclusion of an Anglo-Soviet agreement. He warned that if the Soviet Union stood aside in a European war it might "secure an advantage from the exhaustion of the western powers" and that if negotiations failed, a Nazi-Soviet agreement was a strong possibility. Chamberlain rejected the advice and said he preferred to "extend our guarantees" in eastern Europe rather than sign an Anglo-Soviet alliance. (71)

A debate on the subject took place in the House of Commons on 19th May, 1939. The debate was short and was "practically confined to the leaders of Parties and to prominent ex-Ministers". Chamberlain made it clear that he had severe doubts about Stalin's proposal. David Lloyd George, the former prime minister called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. Clement Attlee had been campaigning for a military alliance with the Soviet Union since September, 1938, during the crisis over Czechoslovakia. (72) Attlee argued in the House of Commons that the government should form a "firm union between Britain, France and the USSR as the nucleus of a World Alliance against aggression". The government was "dilatory and fumbling" and was in danger of letting Stalin slip out of their grasp and into Hitler's hands." (73)

Winston Churchill, made a passionate speech where he urged Chamberlain to accept Stalin's offer: "There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge." (74)

On 24th May, 1939, the Cabinet discussed whether to open negotiations for an Anglo-Soviet alliance. The Cabinet was overwhelmingly in favour of an agreement. This included Lord Halifax who feared that if Britain did not do so the Soviet Union would sign an alliance with Nazi Germany. Chamberlain conceded that "in present circumstances, it was impossible to stand out against the conclusion of an agreement" but he stressed the "question of presentation was of the utmost importance." He therefore insisted that attempts should be made to hide any agreement under the banner of the League of Nations. (75)

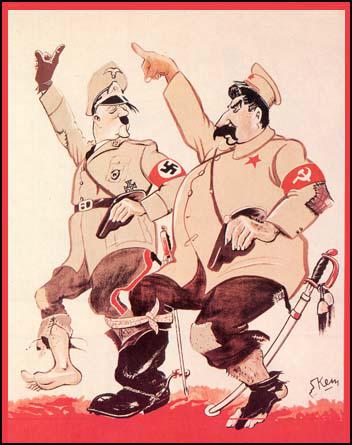

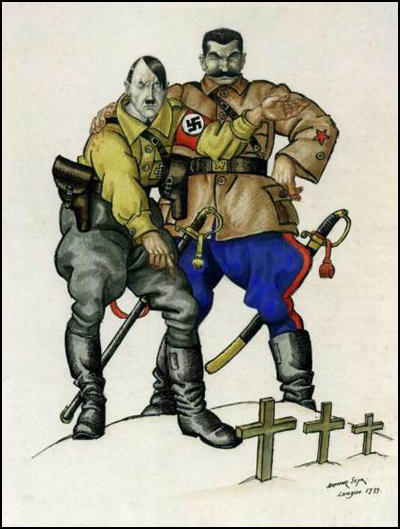

Russian and German Cooperation (1939)

Stalin's own interpretation of Britain's response of his plan for an anti-fascist alliance, was that they were involved in a plot with Germany against the Soviet Union. This belief was reinforced when Chamberlain met with Adolf Hitler at Munich and gave into his demands for the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. Stalin now believed that the main objective of British foreign policy was to encourage Germany to head east rather than west. Stalin now decided to develop a new foreign policy. Stalin realized that war with Germany was inevitable. However, to have any chance of victory he needed time to build up his armed forces. The only way he could obtain time was to do a deal with Hitler. Stalin was convinced that Hitler would not be foolish enough to fight a war on two fronts. If he could persuade Hitler to sign a peace treaty with the Soviet Union, Germany was likely to invade Western Europe instead. (76)

Negotiations continued between Britain and the Soviet Union. The main stumbling-block concerned the rights of the Soviets to "rescue any Baltic state from Hitler, even if it did not want to be rescued". Britain insisted that they would only cooperate with Soviet Russia if Poland were attacked and agreed to accept Soviet assistance. This deadlock could not be broken and Molotov suggested that they concentrated on military talks. However, the British representatives in the talks were instructed to "go very slowly". The negotiations finally ended in failure on 21st August. (77)

Molotov now began secret negotiations with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. He later claimed: "To seek a settlement with Russia was my very own idea which I urged on Hitler because I sought to create a counter-weight to the West and because I wanted to ensure Russian neutrality in the event of a German-Polish conflict. After a short ceremonial welcome the four of us sat down at a table: Stalin, Molotov, Count Schulenburg and myself.... Stalin spoke - briefly, precisely, without many words; but what he said was clear and unambiguous and showed that he, too, wished to reach a settlement and understanding with Germany. Stalin used the significant phrase that although we had 'poured buckets of filth' over each other for years there was no reason why we should not make up our quarrel." (78)

On 28th August, 1939, the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed in Moscow. It was reported: "Late Sunday night - not the usual time for such announcements - the Soviet Government revealed a pact, not with Great Britain, not with France, but with Germany. Germany would give the Soviet Union seven-year 5% credits amounting to 200,000,000 marks ($80.000,000) for German machinery and armaments, would buy from the Soviet Union 180,000.000 marks' worth ($72,000,000) of wheat, timber, iron ore, petroleum in the next two years". (79) Apparently, the day after the agreement was signed, Stalin told Lavrenti Beria: "Of course, it's all a game to see who can fool whom. I know what Hitler's up to. He thinks he's outsmarted me, but actually it's I who have tricked him." (80)

Lord Halifax argued that the Nazi-Soviet Pact did not make any difference as British policy had "always discounted Russia, so materially the position is not really changed." (81) On 22nd August, 1939, Chamberlain told the Cabinet, "It is unthinkable that we would not carry out our obligations to Poland." (82) Despite these comments he sent Hitler and unequivocal letter, approved by the Cabinet, which stated that Britain intended to stand by Poland. On 24th August, Chamberlain gained parliamentary agreement to pass the Emergency Powers Act. The following day, a formal Anglo-Polish military alliance was signed, to reinforce the British resolve not to abandon Poland. (83)

On 25th August, 1939, Hitler sent a letter to Chamberlain in which he demanded the Danzig and Polish corridor questions be settled immediately. In return for a settlement, Hitler offered a non-aggression pact to Britain and promised to guarantee the British Empire and to sign a treaty of disarmament. (84) Some appeasers such as Nevile Henderson, Richard Austen Butler and Horace Wilson, wanted to do a deal with Hitler. They were accused by Oliver Harvey of "working like beavers for a Polish Munich". (85)

The reply to Hitler went through several drafts, until it was finally agreed by the whole Cabinet on 28th August. In the letter, Chamberlain suggested direct Polish-German talks to settle the issue peacefully, but would not "acquiesce in a settlement which put in jeopardy the independence of the state to whom they had given their guarantee." (86) In response, Hitler demanded a Polish emissary "with full powers" go to Berlin on 30th August 1939, but the Polish government refused. (87)

On 31st August, 1939, Adolf Hitler gave the order to attack Poland. The following day fifty-seven army divisions, heavily supported by tanks and aircraft, crossed the Polish frontier, in a lightning Blitzkrieg attack. A telegram was sent to Hitler warning of the possibility of war unless he withdrew his troops from Poland. That evening Chamberlain told the House of Commons: "Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall on me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitration of war. I fear I may not be able to avoid that responsibility". (88)

At a meeting of the Cabinet on 2nd September, the Cabinet wanted the prime minister to declare war on Germany. Chamberlain refused and argued it was still possible to avoid conflict. That night he announced in the House of Commons that he was offering Hitler a conference to discuss the subject of Poland if the "Germans agreed to withdraw their forces (which was not the same as actually withdrawing them), the British government would forget everything that had happened, and diplomacy could start again." (89)

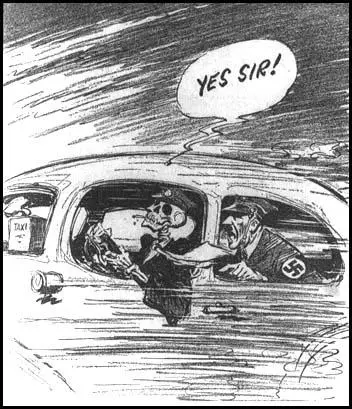

goldfish!" The Daily Mail (17th November, 1939)

Clement Attlee was not in the House of Commons as he was recovering from a serious operation. It was acting leader, Arthur Greenwood, who replied to Chamberlain's statement. As he stood up, Leo Amery shouted "Speak for England, Arthur!". Greenwood said: "I am gravely disturbed. An act of aggression took place 38 hours ago. The moment that act of aggression took place one of the most important treaties of modern times automatically came into operation. There may be reasons why instant action was not taken. I am not prepared to say - and I have tried to play a straight game - I am not prepared to say what I would have done had I been one of those sitting on those Benches. That delay might have been justifiable, but there are many of us on all sides of this House who view with the gravest concern the fact that hours went by and news came in of bombing operations, and news today of an intensification of it, and I wonder how long we are prepared to vacillate at a time when Britain and all that Britain stands for, and human civilisation, are in peril. We must march with the French." (90)

Chamberlain had lost the support of his own MPs. He was shocked by this reaction and Lord Halifax commented that he had "never seen the Prime Minister so disturbed". Members of the Cabinet were also angry with Chamberlain's performance in the House of Commons. Several members of the Cabinet assembled in the office of John Simon. He later recalled: "The language and feelings of some of my colleagues were so strong and deep that I thought it right at once to inform the Prime Minister." The men drafted a letter that said "that our view was that in no circumstances should the expiry of the ultimatum go beyond 12 noon tomorrow, and even this extension of twelve hours beyond the Cabinet's earlier decision would only be acceptable if it was the necessary price of French co-operation". (91)

Shortly before midnight, on 2nd September, 1939, the Cabinet met for a second time. Members, led by Leslie Hore-Belisha, argued that the government must stop procrastinating and declare war or else he would be defeated in the House of Commons. It was agreed to issue an ultimatum which would be delivered by Nevile Henderson to the German government in Berlin at 9.00 a.m. on 3rd September 1939. It stated that unless Hitler made a firm promise to withdraw his troops from Poland by 11.00 a.m. then Britain would declare war. (92)

The following day Neville Chamberlain went on radio to announce: "Britain is at war with Germany" and went on to say: "This is a sad day for all of us, and to none is it sadder than to me. Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established." (93)

Richard Lamb, the author of The Ghosts of Peace (1987) described it as a "pathetic broadcast" and "instead of promising speedy help to the ally on whose behalf Britain was going to war, he spoke of his personal grief." Although the people of Poland "expected immediate help, Britain had no intention of coming to Poland's aid." On 9th September, 1939, a Polish military mission led by General Norwid Neugebauer, arrived in London to have talks with William Ironside the Chief of the General Staff. However, all Ironside could offer was a few thousand old rifles and a few million rounds of ammunition, and he advised them to buy arms from neutral countries such as Spain and Belgium. (94)

Of course, leaving the European Union without a deal will not be as bad as being responsible for the Second World War. However, the economic consequences of this decision will last for many years. Those Cabinet ministers in 1938 could have brought an end to the disastrous policy of appeasement by resigning and bringing down the Prime Minister. This is also true of those current ministers who know we are on the verge of making the worst political decision since the belief that Hitler could be appeased. It is time you decided to save your country and resign.

John Simkin (26th February, 2019)

References

(1) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 345

(2) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 27

(3) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (26th March, 1936)

(4) Patricia Knight, The Spanish Civil War (1998) page 67

(5) Antony Beevor, The Spanish Civil War (1982) page 110

(6) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (29th October, 1936)

(7) G. T. Waddington, Eric Phipps : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(8) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 53

(9) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 17

(10) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 74

(11) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 14

(12) Neville Henderson, speech in Berlin (1st June, 1937)

(13) Alfred Knox, speech in House of Commons (9th June 1937)

(14) Richard Griffiths, Fellow Travellers of the Right (1979) page 283

(15) Jim Wilson, Nazi Princess: Hitler, Lord Rothermere and Princess Stephanie Von Hohenlohe (2011) page 82

(16) John Charmley, Chamberlain and the Lost Peace (1989) page 6

(17) Anthony Eden, Facing the Dictators (1962) page 511

(18) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 296

(19) Christopher Andrew, Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5 (2010) page 199

(20) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (5th December, 1936)

(21) Lord Halifax, Fullness of Days (1957) page 181

(22) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 74

(23) Peter Neville, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(24) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 21

(25) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 138

(26) Lord Halifax, diary entry (19th November, 1937)

(27) William Strang, memorandum (November, 1937)

(28) Anthony Eden, speech (21st February 1938)

(29) Peter Neville, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(30) Anthony Eden, letter to Stanley Baldwin (11th May, 1938)

(31) David Faber, Munich: The 1938 Appeasement Crisis (2008) pages 169-170

(32) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 147

(33) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 61

(34) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) pages 160-161

(35) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 63

(36) Telford Taylor, Munich: The Price of Peace (1979) page 740

(37) Neville Chamberlain, letter to Ida Chamberlain (19th September, 1938)

(38) Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, diary entry (17th September, 1938)

(39) Thomas Inskip, Minister for Coordination of Defence, diary entry (17th September, 1938)

(40) David Faber, Munich: The 1938 Appeasement Crisis (2008) page 303

(41) Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, diary entry (17th September, 1938)

(42) Thomas Inskip, Minister for Coordination of Defence, diary entry (19th September, 1938)

(43) Cabinet minutes (17th September, 1938)

(44) Neville Chamberlain, letter to Ida Chamberlain (19th September, 1938)

(45) Richard Crockett, Twillight of Truth: Chamberlain, Appeasement and the Manipulation of the Press (1989) page 79

(46) David Faber, Munich: The 1938 Appeasement Crisis (2008) page 303

(47) Adam Adamthwaite, Journal of Contemporary History (April, 1983) page 288

(48) The Daily Herald (23rd September, 1938)

(49) Maxim Litvinov, speech at the United Nations (22nd September, 1938)

(50) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 65

(51) David Faber, Munich: The 1938 Appeasement Crisis (2008) pages 326-332

(52) Alexander Cadogan, diary entry (24th September, 1938)

(53) Neville Chamberlain, Cabinet minutes (24th September, 1938)

(54) Cabinet minutes (24th September, 1938)

(55) Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, diary entry (24th September, 1938)

(56) Lord Halifax, letter to Neville Chamberlain (23rd September, 1938)

(57) Leo Amery, diary entry (24th September, 1938)

(58) Leo Amery, letter to Lord Halifax (24th September, 1938)

(59) Leo Amery, letter to Neville Chamberlain (25th September, 1938)

(60) Duff Cooper, speech in the House of Commons (3rd October, 1938)

(61) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (3rd October, 1938)

(62) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 177

(63) Robert Sheppard, A Class Divided: Appeasement and the Road to Munich (1988) page 223

(64) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (18th November, 1938)

(65) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 189

(66) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 84

(67) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 80

(68) David Lloyd George, speech in the House of Commons (3rd April, 1939)

(69) The Times (19th March, 1939)

(70) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 80

(71) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 228

(72) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 226

(73) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (19th May, 1939)

(74) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (19th May, 1939)

(75) Cabinet minutes (24th May, 1939)

(76) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996) pages 426-427

(77) A. J. P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965) page 546

(78) Joachim von Ribbentrop Memoirs (1953) page 109

(79) Time Magazine (28th August, 1939)

(80) Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers (1971) page 111

(81) Andrew Roberts, The Holy Fox: A Biography of Lord Halifax (1991) page 167

(82) Cabinet minutes (22nd August, 1939)

(83) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 86

(84) Adolf Hitler, letter to Neville Chamberlain (25th August, 1939)

(85) John Charmley, Chamberlain and the Lost Peace (1989) page 202

(86) Neville Chamberlain, letter to Adolf Hitler (28th August, 1939)

(87) Adolf Hitler, letter to Neville Chamberlain (30th August, 1939)

(88) Neville Chamberlain, speech in the House of Commons (1st September, 1939)

(89) Neville Chamberlain, speech in the House of Commons (2nd September, 1939)

(90) Arthur Greenwood, speech in the House of Commons (2nd September, 1939)

(91) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 341

(92) Cabinet minutes (2nd September, 1939)

(93) Neville Chamberlain, speech on BBC radio (3rd September, 1939)

(94) Richard Lamb, The Ghosts of Peace (1987) page 122

Previous Posts

Robert F. Kennedy was America's first assassination conspiracy theorist (21st January, 2019)

The statement signed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Kathleen Kennedy Townsend (20th January, 2019)

Was Winston Churchill a supporter or an opponent of Fascism? (16th December, 2018)

Why Winston Churchill suffered a landslide defeat in 1945? (10th December, 2018)

The History of Freedom Speech in the UK (25th November, 2018)

Are we heading for a National government and a re-run of 1931? (19th November, 2018)

George Orwell in Spain (15th October, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in Britain today. Jeremy Corbyn and the Jewish Chronicle (23rd August, 2018)

Why was the anti-Nazi German, Gottfried von Cramm, banned from taking part at Wimbledon in 1939? (7th July, 2018)

What kind of society would we have if Evan Durbin had not died in 1948? (28th June, 2018)

The Politics of Immigration: 1945-2018 (21st May, 2018)

State Education in Crisis (27th May, 2018)

Why the decline in newspaper readership is good for democracy (18th April, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in the Labour Party (12th April, 2018)

George Osborne and the British Passport (24th March, 2018)

Boris Johnson and the 1936 Berlin Olympics (22nd March, 2018)

Donald Trump and the History of Tariffs in the United States (12th March, 2018)

Karen Horney: The Founder of Modern Feminism? (1st March, 2018)

The long record of The Daily Mail printing hate stories (19th February, 2018)

John Maynard Keynes, the Daily Mail and the Treaty of Versailles (25th January, 2018)

20 year anniversary of the Spartacus Educational website (2nd September, 2017)

The Hidden History of Ruskin College (17th August, 2017)

Underground child labour in the coal mining industry did not come to an end in 1842 (2nd August, 2017)

Raymond Asquith, killed in a war declared by his father (28th June, 2017)

History shows since it was established in 1896 the Daily Mail has been wrong about virtually every political issue. (4th June, 2017)

The House of Lords needs to be replaced with a House of the People (7th May, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Caroline Norton (28th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Mary Wollstonecraft (20th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Anne Knight (23rd February, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Elizabeth Heyrick (12th January, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons: Where are the Women? (28th December, 2016)

The Death of Liberalism: Charles and George Trevelyan (19th December, 2016)

Donald Trump and the Crisis in Capitalism (18th November, 2016)

Victor Grayson and the most surprising by-election result in British history (8th October, 2016)

Left-wing pressure groups in the Labour Party (25th September, 2016)

The Peasant's Revolt and the end of Feudalism (3rd September, 2016)

Leon Trotsky and Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party (15th August, 2016)

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of England (7th August, 2016)

The Media and Jeremy Corbyn (25th July, 2016)

Rupert Murdoch appoints a new prime minister (12th July, 2016)

George Orwell would have voted to leave the European Union (22nd June, 2016)

Is the European Union like the Roman Empire? (11th June, 2016)

Is it possible to be an objective history teacher? (18th May, 2016)

Women Levellers: The Campaign for Equality in the 1640s (12th May, 2016)

The Reichstag Fire was not a Nazi Conspiracy: Historians Interpreting the Past (12th April, 2016)

Why did Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst join the Conservative Party? (23rd March, 2016)

Mikhail Koltsov and Boris Efimov - Political Idealism and Survival (3rd March, 2016)

Why the name Spartacus Educational? (23rd February, 2016)

Right-wing infiltration of the BBC (1st February, 2016)

Bert Trautmann, a committed Nazi who became a British hero (13th January, 2016)

Frank Foley, a Christian worth remembering at Christmas (24th December, 2015)

How did governments react to the Jewish Migration Crisis in December, 1938? (17th December, 2015)

Does going to war help the careers of politicians? (2nd December, 2015)

Art and Politics: The Work of John Heartfield (18th November, 2015)

The People we should be remembering on Remembrance Sunday (7th November, 2015)

Why Suffragette is a reactionary movie (21st October, 2015)

Volkswagen and Nazi Germany (1st October, 2015)

David Cameron's Trade Union Act and fascism in Europe (23rd September, 2015)

The problems of appearing in a BBC documentary (17th September, 2015)

Mary Tudor, the first Queen of England (12th September, 2015)

Jeremy Corbyn, the new Harold Wilson? (5th September, 2015)

Anne Boleyn in the history classroom (29th August, 2015)

Why the BBC and the Daily Mail ran a false story on anti-fascist campaigner, Cedric Belfrage (22nd August, 2015)

Women and Politics during the Reign of Henry VIII (14th July, 2015)

The Politics of Austerity (16th June, 2015)

Was Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, murdered? (31st May, 2015)

The long history of the Daily Mail campaigning against the interests of working people (7th May, 2015)

Nigel Farage would have been hung, drawn and quartered if he lived during the reign of Henry VIII (5th May, 2015)

Was social mobility greater under Henry VIII than it is under David Cameron? (29th April, 2015)

Why it is important to study the life and death of Margaret Cheyney in the history classroom (15th April, 2015)

Is Sir Thomas More one of the 10 worst Britons in History? (6th March, 2015)

Was Henry VIII as bad as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? (12th February, 2015)

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)