Spartacus Blog

Donald Trump and the History of Tariffs in the United States

Monday, 12th March, 2018

Donald Trump announced on 8th March, that he plans to impose a 25% tariff on imports of steel, and a 10% tariff on aluminum. The executive order was signed the following day. Trump promised during the presidential campaign to protect US steelworkers’ jobs, but his plan was opposed by top economic adviser Gary Cohn, who argued that the impact on trade and on companies using cheap steel imports would outweigh any benefits of the tariffs. For example, about 6.5m people are employed in the U.S. in businesses that use steel and aluminum. It was no surprise that more than 100 Republican House members signed a letter expressing “deep concern” about the plan. They pressed Trump to change course and “avoid unintended negative consequences to the US economy and its workers”. They added that “tariffs are taxes that make US businesses less competitive and US consumers poorer.” (1)

Trump has taken this action because of the growing problem with importing too many foreign goods. The United States has the world's largest trade deficit. It's been that way since 1975. The deficit in goods and services was $566 billion in 2017. Imports were $2.895 trillion and exports were only $2.329 trillion. The U.S. trade deficit in goods, without services, was $810 billion. The United States exported $1.551 trillion in goods. The biggest categories were commercial aircraft, automobiles, and food. It imported $2.361 trillion. The largest categories were automobiles, petroleum, and cell phones. (2)

More than 65 percent of the U.S. trade deficit in goods is with China. The $375 billion deficit with China was created by $506 billion in imports. The main Chinese imports are consumer electronics, clothing, and machinery. America only exported $130 billion in goods to China. The U.S. also has a trading deficit with Mexico ($71 billion), Japan ($69 billion), Germany ($65 billion), Canada ($18 billion) and the United Kingdom ($13 billion). (3)

The U.S. has a trading deficit of $92 billion with the European Union. On 10th March, President Trump, using his unusual negotiating style, tweeted: "The European Union, wonderful countries who treat the U.S. very badly on trade, are complaining about the tariffs on Steel & Aluminum. If they drop their horrific barriers & tariffs on U.S. products going in, we will likewise drop ours. Big Deficit. If not, we Tax Cars etc. FAIR!" (4)

But will this tactic work. Take the case of an automobile. A Volkswagen Beetle can be assembled in Mexico and exported to the European Union with no import tax. But if that same car were sent to Europe after being manufactured at a VW plant in Tennessee, the EU would impose an import tariff of 10 per cent. Trump is suggesting that the U.S. would raise its tax on imports of a BMW assembled in Germany to the European 10 per cent tariff unless the EU unilaterally lowered its auto tariffs to U.S. levels of 2.5 percent. However, imposing a 10 per cent tariffs on imports of German-assembled BMWs would do nothing for American-based automakers seeking sales in Europe unless the EU lowered its tariffs to zero on American arrivals. (5)

It would probably help Trump to take a look at the history of tariffs in the United States. The first tariff law passed by the U.S. Congress, took place in 1789. Its purpose was to generate revenue for the federal government. An Import tax was collected by treasury agents before goods could be landed at U.S. ports. For the next 150 years tariffs were the greatest source of federal revenue. One politician in 1888 explained why he was against the idea of free trade: "Free foreign trade gives our money, our manufactures, and our markets to other nations to the injury of our labor, our trades people, and our farmers. Protection keeps money, markets, and manufactures at home for the benefit of our own people." (6)

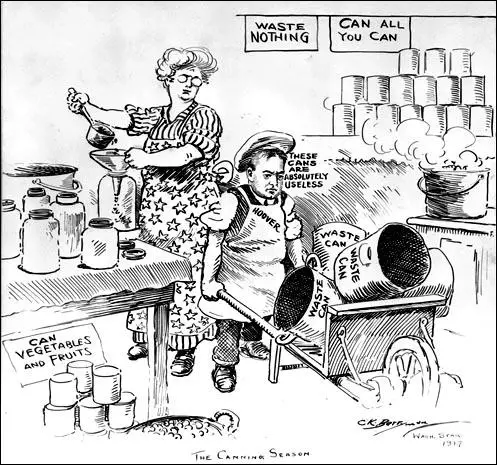

During the 1896 Presidential Election the Republican Party candidate, William McKinley, promised to take action to protect the home market. The following year, the Dingley Act imposed duties on wool and hides which had been duty-free since 1872. Rates were increased on woolens, linens, silks, china, and sugar (the tax rates for which doubled). Over the next 12 years it imposed an average of 46.5 per cent. (7)

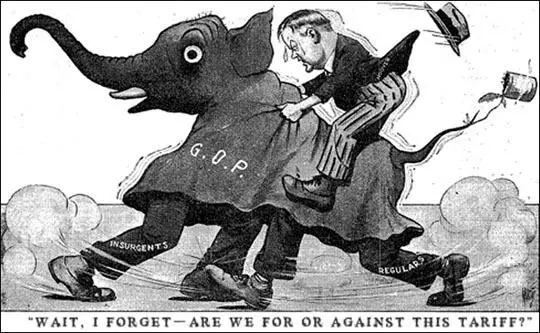

In 1909 President William Howard Taft called Congress into a special session to discuss the tariff issue. This resulted in the Payne-Aldrich Act. This reduced some tariffs and increased others. The issue was very controversial and led to a deep split in the Republican Party. Overall it reduced to tariffs to about 40.8 per cent. This was followed by the Underwood-Simmons Tariff in 1913 that lowered rates to 25 per cent. (8)

During the First World War the situation changed dramatically when President Woodrow Wilson decided to intervene in the market. On 10th August, 1917, Herbert Hoover was appointed as head of the United States Food Administration, an agency responsible for the administration of the U.S. army overseas and allies' food reserves. The new law forbade hoarding, waste, and "unjust and unreasonable" prices and required businesses to be licensed. During this period "Hooverize" entered the dictionary as a synonym for economizing on food. (9)

One senator protested that Wilson had given Hoover "a power such as no Caesar ever employed over a conquered province in the bloodiest days of Rome's bloody despotism". Hoover replied that, "Winning a war requires a dictatorship of some kind or another. A democracy must submerge itself temporarily in the hands of an able man or an able group of men. No other way has ever been found." (10)

Hoover's main objectives was to persuade farmers to grow more and grocery shoppers to buy less so that surplus food should be sent to America's overseas allies. Hoover established set days for people to avoid eating specified foods and save them for soldiers' rations. For example, people were told not to eat meat on Mondays. In January, 1918, Hoover announced "the law of supply and demand... had been suspended." (11)

As head of the Food Administration's Grain Corporation, he informed millers that if they did not sell flour to the government at a price he determined, he would requisition it, and he told bakers they must make "victory bread or close." In another speech Hoover argued: "The law is not sacred... Its unchecked operation might even jeopardize our success in war... It is imperative... that economic thinkers denude themselves of their procrustean forumulas of supply and demand... for in a crisis... government must necessarily regulate the price, and all theories to the contrary go by the board." (12)

As a result of these measures farmers enjoyed rising prices and profits during the final stages of the war. This led to increased output and farmers borrowed heavily to expand their acreage. For example, gross farm income in 1919 amounted to $17.7 billion. However, after the war prices began to fall and by 1921 total farm incomes amounted to only $10.5 billion.

During the 1920 Presidential Campaign the Republican candidate, Warren Harding, promised to take measures to protect American farmers. It was thought that the rates under the Underwood-Simmons Act was too low. Joseph Fordney, the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, and Porter McCumber, the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, introduced a bill which authorized the "Tariff Commission, working in an 'expert' and unpolitical way (and thus supposedly also independently of economic interests), to set rates so as to equalize the difference between American and foreign costs of production." (13)

In September 1922, the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act was signed by President Harding. These raised tariffs to levels higher than any previously in American history in an attempt to bolster the post-war economy, protect new war industries, and aid farmers. "Duties on chinaware, pig iron, textiles, sugar, and rails were restored to the high levels of 1907 and increases ranging from 60 to 400 per cent were established on dyes, chemicals, silk and rayon textiles, and hardware." (14) Over the next eight years it raised the American ad valorem tariff rate to an average of about 38.5% for dutiable imports and an average of 14% overall. It has been claimed that the tariff was defensive, rather than offensive. (15)

In response to the Fordney-McCumber, most of American trading partners had raised their own tariffs to counter-act this measure. The Democratic Party that had opposed tariffs argued that it was to blame for the agricultural depression that took place during the 1920s. Senator David Walsh pointed out that farmers were net exporters and so did not need protection. He explained that American farmers depended on foreign markets to sell their surplus. The price of farming machinery also increased. For example, the average cost of a harness rose from $46 in 1918 to $75 in 1926, the 14-inch plow rose from $14 to $28, mowing machines rose from $45 to $95, and farm wagons rose from $85 to $150. Statistics of the Bureau of Research of the American Farm Bureau that showed farmers had lost more than $300 million annually as a result of the tariff. (16)

The farming community had not enjoyed the benefits of this growing economy. As Patrick Renshaw has pointed out: "The real problem was that in both agricultural and industrial sectors of the economy America's capacity to produce was tending to outstrip its capacity to consume. This gap had been partly bridged by private debt, easy credit, easy credit and hire purchase. But this would collapse if anything went wrong in another part of the system." (17)

Industrialists such as Henry Ford attacked the tariff and argued that the American automobile industry did not need protection since it dominated the domestic market and its main objective was to expand foreign sales. He pointed out that France raised its tariffs on automobiles from 45% to 100% in response to the measure. Ford and other industrialists tended to favour the idea of free trade. (18)

President Herbert Hoover

President Calvin Coolidge announced in August 1927 that he would not seek a second full term of office. Coolidge was unwilling to nominate Herbert Hoover as his successor. The two men had a poor relationship on one occasion he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice - all of it bad. I was particularly offended by his comment to 'shit or get off the pot'." (19)

Coolidge was not alone in thinking that Hoover might be a bad candidate. Republican leaders cast about for an alternative candidate such as Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and the former Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Despite these reservations, Hoover won the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention. Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas was selected as his running-mate. One newspaper reported: "Hoover brings character and promise to the Republican ticket. He is a new kind of candidate in a day surfeited with old forms and old habits in politics." (20)

Although agriculture sector had problems during the 1920s, American industry prospered. The real wages of industrial workers increased by about 10 per cent during this period. However, productivity rose by more than 40%. Semi-skilled and unskilled workers in mass production, who were not unionized, lagged far behind skilled craftsmen and therefore there was a growth in inequality: "The average industrial wage rose from 1919's $1,158 to $1,304 in 1927, a solid if unspectacular gain, during a period of mainly stable prices... The twenties brought an average increase in income of about 35%. But the biggest gain went to the people earning more than $3,000 a year.... The number of millionaires had risen from 7,000 in 1914 to about 35,000 in 1928." (21)

Hoover and the Republicans believed the Forder-McCumber tariffs had helped the American economy to grow. William Borah, the charismatic senator from Idaho, widely regarded as a true champion of the American farmer, had a meeting with Hoover and offered to give him his full support if he promised to increase tariffs of agricultural products if elected. (22) Hoover agreed with the proposal and during the campaign promised the American electorate that he would revise the tariff. (23)

Carter Field argued that the business community was pleased with the election of Hoover: "In the months following the election of Hoover, in 1928, there was a wild stock-market boom. Most speculators, most businessmen, most people thought the country was moving on to a new high plateau of prosperity. Hoover was the miracle man. He knew about business and would help it prosper. Stocks were already high the day Hoover was elected; for example, American Telephone, which was sold around 150 in the spring of 1927 and was about 200 on election day, 1928, soared to a high above 310." (24)

1930 Smoot-Hawley Act

After his election Hoover asked Congress for an increase of tariff rates for agricultural goods and a decrease of rates for industrial goods. Reed Smoot from Utah and chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and Willis C. Hawley, from Oregon, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, agreed to sponsor the proposed bill. Individual members of Congress were under great pressure from industry lobbyists to raise tariffs to protect them from the negative effects of foreign imports. Therefore, when it passed by the House of Representatives the president's bill was completely changed and now included rate hikes covering 887 specific products. (25)

Patrick Renshaw has pointed out: "The real problem was that in both agricultural and industrial sectors of the economy America's capacity to produce was tending to outstrip its capacity to consume. This gap had been partly bridged by private debt, easy credit, easy credit and hire purchase. But this would collapse if anything went wrong in another part of the system." (26) Smoot and Hawley argued that raising the tariff on imports would alleviate the over-production problem. In May 1929, the House of Representatives passed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff bill on a vote of 264 to 147, with 244 Republicans and 20 Democrats voting in favor of the bill. (27)

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff bill was then debated in the Senate. It came under attack from Democrats. Reed Smoot defended the bill by arguing: "This government should have no apology to make for reserving America for Americans. That has been our traditional policy. ever since the United States became a nation. We have returned to participate in the political intrigues of Europe, and we will not compromise the independence of this country for the privilege of serving as schoolmaster for the world. In economics as in politics, the policy of the government is, "America First". The Republican Party will not stand by and see economic experimenters fritter away our national heritage." (28)

The Senate debated its bill until March 1930, with many Senators trading votes based on their states' industries. Eventually, the revised bill proposed raising taxes on more than 20,000 imported goods to record levels. Willis C. Hawley predicted that it would bring "a renewed era of prosperity". Another supporter, Frank Crowther, argued that "business confidence will be immediately restored. We shall gradually work out of the temporary slump we have been in for the last few months... We shall dissipate the dark clouds of your gloomy prophecy with the rising sunshine of continued prosperity." (29)

The Smoot-Hawley bill was passed in the Senate on a vote of 44 to 42, with 39 Republicans and 5 Democrats voting in favor of the bill. In an attempt to persuade Hoover to veto the legislation, 1,028 American economists, including Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, who was considered the most important economist of the period, published a open letter on the subject. (30)

"We are convinced that increased protective duties would be a mistake. They would operate, in general, to increase the prices which domestic consumers would have to pay. By raising prices they would encourage concerns with higher costs to undertake production, thus compelling the consumer to subsidize waste and inefficiency in industry. At the same time they would force him to pay higher rates of profit to established firms which enjoyed lower production costs. A higher level of protection, such as is contemplated by both the House and Senate bills, would therefore raise the cost of living and injure the great majority of our citizens."

The letter went on to point out that since the Wall Street Crash had resulted in much higher-rates of unemployment: "America is now facing the problem of unemployment. Her labor can find work only if her factories can sell their products. Higher tariffs would not promote such sales. We can not increase employment by restricting trade. American industry, in the present crisis, might well be spared the burden of adjusting itself to new schedules of protective duties. Finally, we would urge our Government to consider the bitterness which a policy of higher tariffs would inevitably inject into our international relations. The United States was ably represented at the World Economic Conference which was held under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1927. This conference adopted a resolution announcing that 'the time has come to put an end to the increase in tariffs and move in the opposite direction.' The higher duties proposed in our pending legislation violate the spirit of this agreement and plainly invite other nations to compete with us in raising further barriers to trade. A tariff war does not furnish good soil for the growth of world peace." (31)

Henry Ford spent an evening at the White House trying to convince President Herbert Hoover to veto the bill, calling it "an economic stupidity." Thomas W. Lamont, the chief executive of J. P. Morgan Investment Bank said he "almost went down on his knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot tariff." He warned that the act would intensify "nationalism all over the world.” (32)

President Hoover considered the bill "vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious" but according to his biographer, Charles Rappleye, "the president could hardly turn its back on a measure endorsed by a clear majority of his own party." (33) Hoover signed the bill on 17th June, 1930. The Economist Magazine argued that the passing of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was "the tragic-comic finale to one of the most amazing chapters in world tariff history… one that Protectionist enthusiasts the world over would do well to study.” (34)

At the time the Smoot-Hawley bill was passed the United States had 4.3 million unemployed. By 1932 it was 12.0 million. United States imports fell 40% in the two years after Smoot-Hawley Act was passed. The economist, David Blanchflower, has argued that the "Smoot-Hawley Tariff proved to be the most damaging piece of trade legislation in US history." (35)

1934 Reciprocal Tariff Act

In 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Cordell Hull as his Secretary of State. Hull considered himself as an internationalist and was a strong advocate of free trade. Hull regarded himself as a follower of the economic theories of Adam Smith and as a disciple of "Locke, Milton, Pitt, Burke, Gladstone, and the Lloyd George school." (36)

Hull knew that America would never adopt free trade but believed the best policy was to empower Roosevelt to negotiate agreements with other nations to lower duties. In 1934 Hull won the support of Henry Wallace, Secretary of Agriculture, who argued in a pamphlet, America Must Choose: The Advantages and Disadvantages of Nationalism, of World Trade, and of a Planned Middle Course (1934), that the only alternative to burgeoning foreign trade was a controlled economy. (37)

President Roosevelt was now convinced the Smoot-Hawley Tariff had played a significant role in the Great Depression. He believed that Congress should not be directly involved in such issues. On 2nd March, 1934, Roosevelt asked Congress for authority to negotiate tariff agreements. "Other governments are to an ever-increasing extent winning their share of international trade by negotiated reciprocal trade agreements. If American agricultural and industrial interests are to retain their deserved place in this trade, the American government must be in a position to bargain for the place with other governments by rapid and decisive negotiation based upon a carefully considered program, and to grant with discernment corresponding opportunities in the American market for foreign products supplementary to our own." (38)

The President's request met strenuous opposition from business interests and from Republican congressmen, who objected both to lowering duties and to surrendering yet another congressional prerogative. (39) However, as Cordell Hull pointed out: "In both House and Senate we were aided by the severe reaction of public opinion against the Smoot-Hawley Act." (40)

On 29th March, the House of Representatives, adopted the bill 274-111, only two Republicans voted for it. The Democrats also controlled the Senate and the Reciprocal Tariff Act was passed on 12th June. This gave power to the president to raise or lower existing tariff rates up to 50 per cent for countries which would reciprocate with similar concessions for American products. In the next four years, Hull concluded eighteen such treaties. (41)

Businessmen like James D. Mooney, vice-president of General Motors, and Thomas A. Morgan, president of Curtiss-Wright, urged Roosevelt to recognition of the Soviet Union. They believed that it would lead to a revival of trade with the world's largest buyer of American industrial and agricultural equipment. Catholic leaders opposed any action that might appear to sanction bolshevism, Roy Wilson Howard, head of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, observed: "I think the menace of Bolshevism in the United States is about as great as the menace of sunstroke in Greenland or chilblains in the Sahara." Thomas J. Watson, president of International Business Machines, asked every American, in the interest of good relations, to "refrain from making any criticism of the present form of Government adopted by Russia." (42)

Trade Tariffs since the Second World War

Reciprocity was an important tenet of the trade agreements brokered under RTAA because it gave Congress more of an incentive to lower tariffs. As more foreign countries entered into bilateral tariff reduction deals with the United States, American exporters had more incentive to lobby Congress for even lower tariffs across many industries. President Dwight Eisenhower admitted that when he came to power some congressional Republicans "were unhappy with the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, and a few even hoped we could restore the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, a move which I knew would be ruinous." (43)

By the time President Lyndon Baines Johnson came to power the debate over tariffs seemed to be over: "What captain of industry or what union leader in this country really yearns and is eager to return to the days of Smoot-Hawley? For the world of you-know-what-deep depressions, rampant unemployment, low profits, if any and, generally, losses... Any move to raise tariffs would set a chain reaction of counter-protection and retaliation that would put in jeopardy our ability to work together and to prosper together... The days of declining trade barriers in a world of unprecedented prosperity and growth is something we want to continue." (44)

In 1975 United States recorded a trade deficit. It has been that way every since. However, senior politicians in the 1970s and the 1980s had grown up during the Great Depression. This included Ronald Reagan who refused to take action. In 1984 he commented: "I have been around long enough to remember that when we did that once before in this century, something called Smoot-Hawley, we lived through a nightmare." (45)

In 2002, President George W. Bush applied sweeping steel tariffs in 2002, but he exempted Canada and Mexico because the US has a critical trade agreement with them, NAFTA. However, history shows that imposing tariffs to protect one industry often results in pain for another. A study found that the move had cost the United States about 200,000 jobs. These tariffs were dropped a year later when the World Trade Organization ruled them illegal. (46)

Barack Obama, like Bill Clinton before him, have campaigned on the perils of free trade only to drop the rhetoric once installed in the White House. Dominic Rushe has argued: "Free traders may have become complacent after hearing tough talk on trade from so many presidential candidates on the campaign trail only to watch them furiously back-pedal when they get into office". (47)

As Douglas A. Irwin, the author of Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression (2017) pointed out: "The Tariff of 1930 proved to be the last time Congress ever determined the specific rates of duty that applied to U.S. imports. Since World War II, a series of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements have reduced U.S. tariffs to levels that would have shocked Smoot and Hawley. Whereas the average tariff on dutiable imports was 45 per cent in 1930, it was less than 5 per cent in 2010." (48)

This makes trading with other countries who do not believe in free trade very difficult. The U.S. steel and aluminum. industries argue that they have faced an existential assault for more than a decade from China, which has become the world’s largest producer of both metals and has flooded global markets with cheap products. But following a series of product and country-specific tariffs introduced in recent years, China now accounts for very little of the steel or aluminum. imported into the U.S. Instead, the leading source for the US of both metals is Canada. Other major Nato members such as Germany are also major exporters of steel to the US. (49)

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the World Bank and The International Monetary Fund have all condemned the high tariffs on steel and aluminum.European Council President Donald Tusk immediately made it clear that the EU would retaliate: “President Trump has recently said ‘trade wars are good and easy to win’ but the truth is quite the opposite. Trade wars are bad and easy to lose..” Brussels trade commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom said "certain goods like cranberries, Florida orange juice, Levi’s jeans, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, peanut butter, Kentucky bourbon and whiskey are on a provisional list of goods that could see high tariffs as a retaliation." (50)

As President Franklin D. Roosevelt pointed out 84 years ago: "If the American government is not in a position to make fair offers for fair opportunities, its trade will be superseded. If it is not in a position at a given moment rapidly to alter the terms on which it is willing to deal with other countries, it cannot adequately protect its trade against discriminations and against bargains injurious to its interests." (51)