On this day on 28th April

On this day in 1831 a mob attacked the house of Duke of Wellington and broke about thirty windows. Wellington, who was prime minister at the time, had refused to reform Parliament. told his friend Harriet Arbuthnot: " I learn from John that the mob attacked my House and broke about thirty windows. He fired two blunderbusses in the air from the top of the house, and they went off... I think that my servant John saved my house, or the lives of many of the mob - possibly both - by firing as he did. They certainly intended to destroy the house, and did not care one pin for the poor Duchess being dead in the house.

A few days later he wrote: "Matters appear to be going as badly as possible. It may be relied upon that we shall have a revolution. I have never doubted the inclination and disposition of the lower orders of the people. I told you years ago that they are rotten to the core. They are not bloodthirsty, but they are desirous of plunder. They will plunder, annihilate all property in the country. The majority of them will starve; and we shall witness scenes such as have never yet occurred in any part of the world."

On 22nd September 1831, the House of Commons passed the Reform Bill. According to Thomas Macaulay: "Such a scene as the division of last Tuesday I never saw, and never expect to see again. If I should live fifty years the impression of it will be as fresh and sharp in my mind as if it had just taken place. It was like seeing Caesar stabbed in the Senate House, or seeing Oliver taking the mace from the table, a sight to be seen only once and never to be forgotten. The crowd overflowed the House in every part. When the doors were locked we had six hundred and eight members present, more than fifty five than were ever in a division before".

The following month the Tories blocked the measure in the House of Lords. Grey asked William IV to dissolve Parliament so that the Whigs could show that they had support for their reforms in the country. Grey explained this would help his government to carry their proposals for parliamentary reform. William agreed to Grey's request and after making his speech in the House of Lords, walked back through cheering crowds to Buckingham Palace.

Polling was held from 28th April to 1st June 1831. In Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended demonstrations in favour of parliamentary reform. William Lovett, the head of the National Union of the Working Classes, gave his support to the reformers standing in the election. The Whigs won a landslide victory obtaining a majority of 136 over the Tories. After Lord Grey's election victory, he tried again to introduce parliamentary reform. Enormous demonstrations took place all over England and in Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended these assemblies. They were overwhelmingly composed of artisans and working men.

On 22nd September 1831, the House of Commons passed the Reform Bill. However, the Tories still dominated the House of Lords, and after a long debate the bill was defeated on 8th October by forty-one votes. When people heard the news, Reform Riots took place in several British towns; the most serious of these being in Bristol in October 1831, when all four of the city's prisons were burned to the ground. In London, the houses owned by the Duke of Wellington and bishops who had voted against the bill in the Lords were attacked. On 5th November, Guy Fawkes was replaced on the bonfires by effigies of Wellington.

Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, complained: "This detestable Reform Bill has raised the hopes of the utmost. At Plymouth and the neighbouring towns, the spirit is tremendously bad. The shopkeepers are almost all Dissenters, and such is the rage on the question of Reform at Plymouth, that I have received from several quarters the most earnest requests that I will not come to concentrate a church, as I had engaged to do. They assure me that my own person, and the security of the public peace, would be in the greatest danger."

Lord Grey argued in the House of Commons that without reform he feared a violent revolution would take place: "There is no one more decided against annual parliaments, universal suffrage, and the ballot, than I am. My object is not to favour but to put an end to such hopes and projects." The Poor Man's Guardian agreed and it commented that the ruling class felt that "a violent revolution is their greatest dread".

Grey attempted negotiation with a group of moderate Tory peers, known as "the waverers", but failed to win them over. On 7th May a wrecking amendment was carried by thirty-five votes, and on the following day the cabinet resolved to resign unless the king would agree to the creation of peers. On 7th May 1832, Grey and Henry Brougham met the king and asked him to create a large number of Whig peers in order to get the Reform Bill passed in the House of Lords. William was now having doubts about the wisdom of parliamentary reform and refused.

Lord Grey's government resigned and William IV now asked the leader of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington, to form a new government. Wellington tried to do this but some Tories, including Sir Robert Peel, were unwilling to join a cabinet that was in opposition to the views of the vast majority of the people in Britain. Peel argued that if the king and Wellington went ahead with their plan there was a strong danger of a civil war in Britain. He argued that Tory ministers "have sent through the land the firebrand of agitation and no one can now recall it."

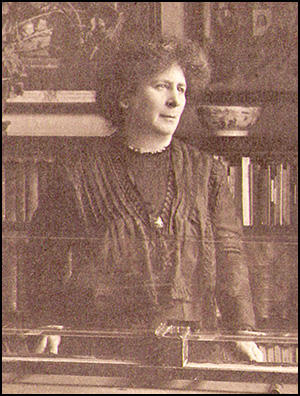

On this day in 1854 Phoebe (Hertha) Marks, the daughter of a watchmaker, was born in Portsea, Hampshire. She was educated at home and one of her tutors was Eliza Orme, who taught her mathematics. From the age of sixteen she worked as a governess. She adopted the name "Hertha" after the heroine of an Algernon Charles Swinburne poem that criticized organized religion.

In 1875 Orme wrote to Helen Taylor, to tell her about the desire of Hertha to study mathematics at Girton College. With the financial help of Taylor and Barbara Bodichon she was able to attend Girton between 1877 and 1881.

After leaving university she taught at Notting Hill and Ealing High School. In 1872 Hertha Marks joined the Hampstead branch of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. In 1885 the line divider she had invented and patented was shown at the Exhibition of Women's Industries organised in Bristol by Helen Blackburn.

In 1885 Hertha married Professor William Ayrton, a widower whose first wife, Matilda Chaplin Ayrton (1846-1883), had been a doctor and a member of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage. He was the father of Edith Ayrton, who was later to play a significant role in the struggle for women's suffrage. Hertha's daughter, Barbara Ayrton, was born in 1886.

Hertha Ayrton continued with her scientific research, working from a laboratory in her house. She also remained active in the London National Society for Women's Suffrage and the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Frustrated by the lack of progress in achieving the vote she accepted that a more militant approach was needed and in 1907 she joined the Women Social & Political Union. Left a considerable amount of money by Barbara Bodichon, she also gave generously to the WSPU. The 1909-10 WSPU accounts show that she gave £1,060 in that year. In 1910 she joined Emmeline Pankhurst and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in a deputation to the House of Commons.

In a letter she wrote to Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Hertha admitted: "I made up my mind some time ago that as I am unable to be militant myself, from reasons of health, and as I believe most fully in the necessity for militancy, I was bound to give every penny I can afford to the militant union that is bearing the brunt of the battle, namely the WSPU."

In March 1912 the British government made it clear that they intended to seize the assets of the WSPU. According to Evelyn Sharp Hertha Ayrton helped to "launder" through her bank account the funds of the WSPU. The WSPU bank manager was subpoenaed to appear at the conspiracy trial and revealed that £7,000 had been paid to "someone named Ayrton".

In November 1912 Hertha Ayrton helped form the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage. The main objective was "to demand the Parliamentary Franchise for women, on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." One member wrote that "it was felt by a great number that a Jewish League should be formed to unite Jewish Suffragists of all shades of opinions, and that many would join a Jewish League where, otherwise, they would hesitate to join a purely political society." Other members included Edith Ayrton, Henrietta Franklin, Hugh Franklin, Lily Montagu, Inez Bensusan and Israel Zangwill.

Militants in the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage disrupted Sabbath worship services in several synagogues in London from early 1913 until the outbreak of First World War, demanding religious as well as political suffrage for women. These women were forcibly removed from synagogues for disrupting services and castigated in the Anglo-Jewish press as “blackguards in bonnets.”

The summer of 1913 saw a further escalation of WSPU violence. In July attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire.

Some leaders of the WSPU such as Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, disagreed with this arson campaign. When Pethick-Lawrence objected, she was expelled from the organisation. Others like Louisa Garrett Anderson and Elizabeth Robins showed their disapproval by ceasing to be active in the WSPU. Sylvia Pankhurst also made her final break with the WSPU and concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London. During this period Hertha Ayrton stopped funding the WSPU.

In February 1914 Hertha became a leading member of the United Suffragists. The group were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form a new organisation. Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Edith Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

During the First World War Hertha Ayrton devised a simple anti-gas fan that could be used in the trenches on the Western Front. Unfortunately, she was unable to persuade the British Army to employ the device.

Hertha Ayrton died on 23rd August 1923.

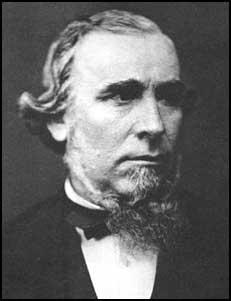

On this day in 1868 Alexander Macdonald gives evidence before the Royal Commission on Trade Unions.

Lord Elcho: What year was it in which you entered the mines?

Alexander Macdonald: About the year 1835 I think; I could not fix the year. I entered the mines at about eight years of age. The condition of the miner's boy then was to be raised about 1 o'clock or 2 o'clock in the morning if the distance was very far to travel, and at that time I had to travel a considerable distance, more than three miles. We remained at the mine until 5 and 6 at night. It was an ironstone mine, very low, working about 18 inches, and in some instances not quite so high. Then I moved to coal mines. There we had low seams also, very low seams. There was no rails to draw upon, that is, tramways. We had leather belts for our shoulders. We had to keep dragging the coal with these ropes over our shoulders, sometimes round the middle with a chain between our legs. Then there was always another behind pushing with his head.

Lord Elcho: That work was done with children?

Alexander Macdonald: That work was done by boys, such as I was, from 10 to 11 down to eight, and I have known them as low as seven years old. In the mines at that time the state of ventilation was frightful.

Lord Elcho: Did that want of ventilation at that time lead to frequent accidents?

Alexander Macdonald: It did not lead to frequent accidents; but it lead to premature death.

Lord Elcho: Not to explosion?

Alexander Macdonald: No; carbonic acid gas in no case leads to explosions. There was no explosive gas in those mines I was in, or scarcely any. I may state incidentally here that in the first ironstone mine I was in there were some 20 or more boys besides myself, and I am not aware at this moment that there is one alive excepting myself.

On this day in 1888 Walter Tull, the son of Daniel Tull, was born at 57 Walton Road, Folkestone. Walter's father, the son of a slave, had arrived from Barbados in 1876 and had found work as a carpenter.

Daniel Tull married Alice Elizabeth Palmer, a young woman from Hougham. Over the next few years the couple had six children. In 1895, when Walter Tull was seven, his mother died of cancer. A year later his father married Alice's cousin, Clara Palmer. She gave birth to a daughter Miriam, on 11th September 1897. Three months later Daniel died from heart disease.

The stepmother was unable to cope with so many children. The resident minister of Grace Hill Wesleyan Chapel, recommended that the two boys of school-age, Walter and Edward, should be sent to the Children's Home and Orphanage (CHO) in Bethnal Green. "Placing the two school-age boys in the home, it was hoped, would prevent the family becoming destitute. The eldest son William was working, and could therefore make his weekly contribution to the family pot, while Alice's two girls - Cecilia, 13 and Elsie, 6 - could help Clara with baby Miriam and the domestic chores. In this set-up, Edward and Walter were liabilities: extra mouths to feed and bodies to clothe."

A letter was sent from the Elham Union to Reverend Stephenson, the man who ran the Methodist orphanage, in January, 1898: "The father of these children was a negro and they are consequently coloured children. I do not know if you are aware of this or whether it will in any way affect the application?" Stephenson replied that it made no difference at all. However, the orphanage was only willing to accept the boys as long as the Elham Union (the Poor Law parish upon which the Tull family relied for money to survive) should continue to contribute towards the boys' upkeep once they had entered the orphanage. The Folkestone Poor Law Guardians eventually agreed to subsidize the living expenses of the boys at the rate of four shillings each per week (plus a suit when they reached 21).

Edward and Walter Tull lived in the orphanage for the next two years. Clara Tull did have the right to claim the boys back. However, if she did, she had to pay eight shillings per week times the length of duration in the orphanage. This meant it was virtually impossible to raise the money needed to reclaim her children. These conditions had to be agreed before the children could even be considered for acceptance into the Children's Home and Orphanage (CHO).

The CHO had the right to send the boys abroad. Over a ten year period they sent 2,000 children to Canada "in its mission of empire-building". However, Edward and Walter did not suffer this fate. Instead they were kept by Stephenson in Bethnal Green. He was on record as saying that he had three aims for children placed in his care: "to teach them a moral code based upon Wesleyan Methodist principles; to provide a basic, elementary education; and to equip boys with a trade and girls with domestic skills".

The CHO formed a choir and the boys were taken on money-raising singing tours. James Warnock, a dentist, spotted Edward Tull during a performance in Glasgow. He arranged to adopt him and his surname was changed to Tull-Warnock. According to the minister of the Claremont Street Wesleyan Church, Warnock "whose clientele is mainly among the poorer people" promised to educate him in dentistry and "treat him as a son". Walter was devastated by the loss of his brother but Edward's parents did what they could to help the boys keep in contact and in July 1903 they sent him 52 shillings to pay for his fare to Scotland.

Walter Tull was apprenticed in the CHO print shop and after he left school at 14 he found work in the printing industry. His ambition was to "get a place on one of the newspapers". He loved playing football and was a member of the Orphanage football team. At the age of 20 it was suggested he should have a trial with Clapton, a successful East London amateur club. He was considered a promising prospect and in October 1908, he was selected to play for the first team at inside-left. That season Clapton won the Amateur Cup, the London Senior Cup and the London County Amateur Cup. The Football Star praised Tull's "clever footwork" and described him as being the "catch of the season".

At the end of the 1908-1909 season Walter Tull was invited to join Tottenham Hotspur, one of the most important clubs in the country. It was a meteoric rise for the young Tull, as it was only four months since making his debut for Clapton's first team. He was invited to go on tour of South America with the club. In May 1909 he played games in Argentina and Uruguay. In a letter he wrote to a friend he commented that he was suffering from "sunstroke and feeling very queer for a few days." According to the English-language daily newspaper the Buenos Aires Herald the players complained that "none of the waiters spoke English".

On his return he was offered a contract to play for Tottenham Hotspur. This created problems for Tull. As Phil Vasili, the author of Colouring Over the White Line (2000), has pointed out: "At the CHO he would have been trained into the Methodist ethos of Muscular Christianity - playing games to develop a fit body and compliant attitude of mind - a doctrine that inferred that being paid to play any sport misses the point of what playing is all about. Muscular Christianity, for the Methodists, was about character building. To play football for wages would change the nature of the game and its players, making profit/winning the ultimate objective rather than the development of a moral character."

On 20th July, 1909, he was paid a £10 signing-on fee (the maximum allowed). Tull was also paid the maximum wage of £4 per week. This had been imposed by the the Football Association in May 1900. It also abolished the paying of all bonuses to players. These restrictions upset professional footballers and in January 1909, the players formed the Association Football Players Union. Led by Billy Meredith, Charlie Roberts, Charlie Sagar, Sandy Turnbull, the leading players at Manchester United, the AFPU threatened strike action unless they were allowed to negotiate their own wages. The AFPU continued to have negotiations with the Football Association but in April 1909 these came to an end without agreement. In June the FA ordered that all players should leave the AFPU. They were warned that if they did not do so by the 1st July, their registrations as professionals would be cancelled. It is therefore highly unlikely that Tull joined the AFPU.

Walter Tull was only the second black man to play professional football in Britain. The first was Arthur Wharton, who signed for Preston North End in 1886. At the time Wharton held the world record for the 100 yards and was was the first black athlete to win an AAA championship. However, he suffered considerable prejudice from the football community. Athletic News, the leading football newspaper in the country, commented: "Good judges say that if Wharton keeps goal for Preston North End in their English Cup tie the odds will be considerably lengthened against them. I am of the same opinion ... Is the darkie's pate too thick for it to dawn upon him that between the posts is no place for a skylark? By some it's called coolness - bosh!"

Tottenham Hotspur had just been promoted to the First Division of the Football League. Tull made his debut against Sunderland. Spurs lost 3-1 and they suffered a second defeat against Everton the following week. They got their first point with a 2-2 draw against Manchester United. In this game Tull caused the opposition defence serious problems and was brought down for a penalty.

Tull got considerable praise for this performance against Manchester United. Jeffrey Green, the author of Black Edwardians (1998) commented: "Walter Tull's first match for Spurs was at their first division debut in 1909. The London team had crowds that numbered thirty thousand, and they thrilled to Tull's skills. He was an inside forward, with the role of supplying the winger with good passes. The Daily Chronicle observed that Tull was a class above many of his team mates. It was felt that had Spurs obtained a decent winger then the combination would have been the best in England. Newspaper reports of Spurs matches refer to Tull as 'West Indian' and 'darkie'. "

One national newspaper, The Daily Chronicle, reported on 9th October, 1909 that "Tull's display on Saturday must have astounded everyone who saw it. Such perfect coolness, such judicious waiting for a fraction of a second in order to get a pass in not before a defender has worked to a false position, and such accuracy of strength in passing I have not seen for a long time. During the first half, Tull just compelled Curtis to play a good game, for the outside-right was plied with a series of passes that made it almost impossible for him to do anything other than well." The newspaper went on to discuss other aspects of his play: "Tull has been charged with being slow, but there never was a footballer yet who was really great and always appeared to be in a hurry. Tull did not get the ball and rush on into trouble. He let his opponents do the rushing, and defeated them by side touches and side-steps worthy of a professional boxer. Tull is very good indeed."

Walter Tull scored his first goal against Bradford City a week later. The Daily Chronicle pointed out that he was "a class superior to that shown by most of his colleagues". In a game against Bristol City on 9th October 1909, Tull was racially taunted by the crowd: "A section of the spectators made a cowardly attack upon him (Walter Tull) in language lower than Billingsgate...Let me tell these Bristol hooligans (there were but few of them in a crowd of nearly twenty thousand) that Tull is so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football whether they be amateur or professional. In point of ability, if not in actual achievement, Tull was the best forward on the field."

However, after playing just seven first-team games he was dropped and played the rest of the season in the reserves. Phil Vasili has raised questions about the reasons for his demotion: "Quite why Tull was never given another chance in the first team that season remains open to speculation, so I will. All that's certain is that he was good enough, when on form, to have merited selection. And there is nothing in the contemporary match reports to suggest a sustained loss of confidence. Wider social pressures may have played a role, especially if the racial abuse Tull received at Bristol was unnerving ambitious directors."

In the 1910-11 season he played in only three games. This included a goal against Manchester City. He also scored 10 goals in 27 league games with the reserves. Disillusioned by his lack of first-team appearances he was transferred for what was said to be a "heavy transfer fee" to Northampton Town in the Southern League. He was signed by Herbert Chapman who was later to become a highly successful manager of Huddersfield Town and Arsenal. Chapman had originally played under Britain's first black player Arthur Wharton, when he was the coach of Stalybridge Rovers. Chapman, Tull and Wharton were all from Methodist backgrounds.

Chapman was only 30 years old in 1910 and created a revolution in football with his coaching methods. When he joined the club as a player in 1907 they were at the bottom of the Southern League. At the time the club was without a manager. As Chapman appeared to be an intelligent man it was suggested by the directors that he should become player-manager. He agreed to do the job on a temporary basis as he still wanted to work full-time as a mining engineer.

At that time tactics were traditionally left to players to work out on the field. Chapman believed in discussing tactics before a game started. For example, Chapman noticed that teams had a tendency to defend in large numbers. Chapman devised a method of playing that drew the opposing defenders from their own goal, and then to hit them on the counter-attack. The strategy was highly successful and that season Northampton Town managed to avoid relegation. The following season they won the Southern League championship with a record 25 wins from 40 games, a record 55 points, and a record 90 goals.

Chapman was always looking to strengthen his side and spent most of his spare-time watching football games. It was when he was watching Tottenham Hotspur reserves that he discovered Walter Tull. Chapman took great care in recruiting players: "I am always sorry for clubs who have to act hurriedly in seeking a new player, for under the most favourable conditions it is a tricky business and demands the closest consideration. It is not enough that a man should be a good player. There are all sorts of other important factors which have to be taken into account. This takes time. The longer I have been on the managerial side of the game, the more I am convinced that all-round intelligence is one of the highest qualifications of the footballer."

He played most of his 110 games for Northampton Town as a wing-half. However, it was only after he switched him to inside forward that he showed his true form and scored four goals in one match. Tull became the club's most popular player. The Northampton Echo reported that: "Tull has now settled in the half-line in a manner which now places him in the front-rank of class players in this position."

James and Helen Warnock arranged for Walter's brother, Edward Tull-Warnock, to train as a dentist at the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow. "Edward was an excellent dental student, taking second prize for both the Dall and Ash Awards." In 1910 he got his first job as an assistant dentist in Birmingham. Upon arriving at the practice, he was met by the dentist, who exclaimed "My God, you're coloured! You'll destroy my practice in 24 hours!" Edward decided to return home and work with his father.

After the death of James Warnock on 4th August, 1914, aged 59 of chronic nephritis, Edward took over his father's dental business at 419 St Vincent Street, Glasgow. It has been claimed that he was probably Britain's first black dentist. He married Elizabeth E. Hutchinson on 28th September 1918 and in 1920 they had a daughter Jean. "Well known in sporting circles he was a member of the Turnberry Golf Club, and the winner of several trophies. In one year he won the Ballantrae Visitors' Cup, the Weir Trophy of the Turnberry Club, and the Glasgow Dental Cup." Edward also developed a local reputation for his fine singing voice. "His fine baritone voice was heard on many occasions as a singer of sacred music and also on the concert platform. In this sphere he excelled with his rendering of Negro Spirituals."

Other clubs wanted to sign Walter Tull and in 1914 Glasgow Rangers began negotiations with Northampton Town. However, before he could play for them the First World War was declared. Tull immediately abandoned his career and offered his services to the British Army. On 21st December, 1914, Tull became the first Northampton Town player to join the Football Battalion (17th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment). At the time it was commanded by Major Frank Buckley.

The Army soon recognized Tull's leadership qualities and he was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant. Tull arrived in France on 18th November 1915. He was initially billeted at Les Ciseaux, 16 miles from the front line. He had still not seen action when he wrote a letter to Edward Tull-Warnock in January 1916: "For the last three weeks my Battalion has been resting some miles distant from the firing line but we are now going up to the trenches for a month or so. Afterwards we shall begin to think about coming home on leave. It is a very monotonous life out here when one is supposed to be resting and most of the boys prefer the excitement of the trenches."

However, once on the Western Front, he found life difficult. In May 1916, he was sent home suffering from "acute mania" (also called shellshock). He soon recovered and was back in action by 20th September. Tull took part in the major Somme offensive, which resulted in 420,000 British casualties. Tull survived this experience but in December 1916 he developed trench fever and was sent home to England to recover.

Walter Tull had impressed his senior officers and recommended that he should be considered for further promotion. When he recovered from his illness, instead of being sent back to France, he went to the officer training school at Gailes in Scotland. Despite military regulations forbidding "any negro or person of colour" being an officer, Tull received his commission in May, 1917.

Walter Tull became the first Black combat officer in the British Army. As Phil Vasili has pointed out in his book, Colouring Over the White Line: "According to The Manual of Military Law, Black soldiers of any rank were not desirable. During the First World War, military chiefs of staff, with government approval, argued that White soldiers would not accept orders issued by men of colour and on no account should Black soldiers serve on the front line."

Lieutenant Walter Tull was sent to the Italian front. This was an historic occasion because Tull was the first ever black officer in the British Army. He led his men at the Battle of Piave and was mentioned in dispatches for his "gallantry and coolness" under fire. "You were one of the first to cross the river Piave prior to the raid on 1st-2nd January, 1918, and during the raid you took the covering party of the main body across and brought them back without a casualty in spite of heavy fire."

Tull stayed in Italy until 1918 when he was transferred to France to take part in the attempt to break through the German lines on the Western Front. On 25th March, 1918, 2nd Lieutenant Tull was ordered to lead his men on an attack on the German trenches at Favreuil. Soon after entering No Mans Land Tull was hit by a German bullet. Tull was such a popular officer that several of his men made valiant efforts under heavy fire from German machine-guns to bring him back to the British trenches. These efforts were in vain as Tull had died soon after being hit. One of the soldiers who tried to rescue him later told his commanding officer that Tull was "killed instantaneously with a bullet through his head."

Tull's body was never found. On 17th April 1918, Lieutenant Pickard wrote to Walter's brother and said: "Being at present in command (the captain was wounded) - allow me to say how popular he was throughout the Battalion. He was brave and conscientious; he had been recommended for the Military Cross, and had certainly earned it, the Commanding Officer had every confidence in him, and he was liked by the men. Now he has paid the supreme sacrifice; the Battalion and Company have lost a faithful officer; personally I have lost a friend. Can I say more, except that I hope that those who remain may be true and faithful as he."

The family of Walter Tull never received the Military Cross. The Ministry of Defence has claimed that there is no record of the Military Cross recommendation was found in Tull's service files at the National Archives. Phil Vasili has argued that it is possible that there are political reasons for this: "Walter Tull was made an officer at a time when the Army was desperately short of men of officer material. I’m convinced that to have given him his Military Cross would have admitted to the powers-that-be at the War Office that rules had been broken in commissioning a black man. But his promotion illustrated the absurdity of their thinking, that white soldiers would not respect black officers."

Edward Tull-Warnock continued with the campaign until his death on 3rd December 1950. Phil Vasili played an important role in this with the publication of his book, Colouring Over the White Line (2000). This was followed by Walter Tull, Officer, Footballer: All the Guns in France Couldn't Wake Me (2009). Dan Lyndon published Walter Tull: Footballer, Soldier, Hero in 2011.

In 2012 Michael Morpurgo, the author of the novel Warhorse (2007), started an online petition urging "the Government to take up Walter’s case – and finally award him his Military Cross posthumously." Morpurgo hopes that eventually there might be a statue of Walter Tull outside the Imperial War Museum in London as "a tribute to one man’s fight against prejudice and evil and an inspiration to new generations".

It was announced on 3rd September, 2014 that Walter Tull will be remembered on a special set of coins released by the Royal Mint as part of commemorations of the centenary of the First World War. The coin, featuring a portrait of the officer with a backdrop of infantry soldiers going "over the top”, will be one of a set of six £5 coins to remember the sacrifice made by so many during the war.

On this day in 1935 Franklin D. Roosevelt makes speech on unemployment.

My most immediate concern is in carrying out the purposes of the great work program just enacted by the Congress. Its first objective is to put men and women now on the relief rolls to work and, incidentally, to assist materially in our already unmistakable march toward recovery. I shall not confuse my discussion by a multitude of figures. So many figures are quoted to prove so many things. Sometimes it depends upon what paper you read and what broadcast you hear. Therefore, let us keep our minds on two or three simple, essential facts in connection with this problem of unemployment. It is true that while business and industry are definitely better our relief rolls are still too large. However, for the first time in five years the relief rolls have declined instead of increased during the winter months. They are still declining. The simple fact is that many million more people have private work today than two years ago today or one year ago today, and every day that passes offers more chances to work for those who want to work. In spite of the fact that unemployment remains a serious problem here as in every other nation, we have come to recognize the possibility and the necessity of certain helpful remedial measures. These measures are of two kinds. The first is to make provisions intended to relieve, to minimize, and to prevent future unemployment; the second is to establish the practical means to help those who are unemployed in this present emergency. Our social security legislation is an attempt to answer the first of these questions. Our work relief program the second. The program for social security now pending before the Congress is a necessary part of the future unemployment policy of the government. While our present and projected expenditures for work relief are wholly within the reasonable limits of our national credit resources, it is obvious that we cannot continue to create governmental deficits for that purpose year after year. We must begin now to make provision for the future. That is why our social security program is an important part of the complete picture. It proposes, by means of old age pensions, to help those who have reached the age of retirement to give up their jobs and thus give to the younger generation greater opportunities for work and to give to all a feeling of security as they look toward old age.

The unemployment insurance part of the legislation will not only help to guard the individual in future periods of lay-off against dependence upon relief, but it will, by sustaining purchasing power, cushion the shock of economic distress. Another helpful feature of unemployment insurance is the incentive it will give to employers to plan more carefully in order that unemployment may be prevented by the stabilizing of employment itself.

On this day in 1938 Esther Roper died of heart failure at her home in Hampstead on 28th April 1938, and was buried alongside Eva Gore-Booth in St John's Churchyard.

Esther Roper, the daughter of the Reverend Edward Roper, was born at Lindow near Chorley on 4th August, 1868. Soon after Esther's birth her parents returned to their missionary work in Africa. She lived with her maternal grandparents until being placed in a children's home in Highbury in 1872.

In 1886 she was admitted to Owens College in Manchester. Roper became interested in the subject of women's suffrage and in 1893 became secretary of the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage. In this role she tried to recruit working-class women from the emerging trade union movement.

Esther Roper met Eva Gore-Booth in Italy in 1896. According to Margaret M. Jensen they "became immediate and lifelong companions". Gifford Lewis the author of Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper (1998), has argued: "For the first time Eva was able to talk to a kindred spirit. Captivated by the woman and her cause, she impulsively decided to leave Ireland and join Esther in the suffrage cause in Manchester."

In 1897 Eva left Ireland and moved into Esther's home in Manchester. This also brought her into contact with Eva's sister, Constance Gore-Booth, who had established the Sligo Women's Suffrage Association the previous year. In 1901, Christabel Pankhurst, who was at that time a student at Manchester University, joined Esther's trade union campaign. She also met her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, who was a member of the the Manchester branch of the NUWSS.

Esther Roper was one of the main speakers at a women's enfranchisement meeting in Westminster in 1902. The following year Esther and Eva established the Lancashire and Cheshire Women's Textile and Other Workers Representation Committee. Esther also co-edited the Women's Labour News, a quarterly journal aimed at uniting women workers. She was also active in the socialist group, the Independent Labour Party.

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that: "Christabel Pankhurst had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family." Sylvia Pankhurst also made comments on this: "Eva Gore-Booth had a personality of great charm... Christabel adored her, and when Eva suffered from neuralgia, as often happened, would sit with her for hours massaging her head. To all of us at home this seemed remarkable indeed, for Christabel had never been willing to act the nurse to any other human being."

In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst, with the help of her three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst, formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At first the main aim of the organisation was to recruit more working class women into the struggle for the vote and therefore initially received the support of Esther and Eva. However, she later disapproved of their use of violence.

She continued to be interested in the struggle for women's rights and in the 1908 joined with Eva Gore-Booth, Constance Markievicz, May Billinghurst, Annie Kenney and Adela Pankhurst, in the campaign against Winston Churchill in the parliamentary election in Manchester North West.

In 1913 Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth moved to London. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, the NUWSS declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although its leader, Millicent Fawcett, supported the First World War effort she did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. Eva and Esther were both pacifists and disagreed with this strategy. Despite pressure from the majority of members, who held similiar views to Esther, Fawcett refused to argue against the war. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union."

In 1914 they joined the No-Conscription Fellowship, an organisation formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has pointed out: "Though limiting itself to campaigning against conscription, the N.C.F.'s basis was explicitly pacifist rather than merely voluntarist.... In particular, it proved an efficient information and welfare service for all objectors; although its unresolved internal division over whether its function was to ensure respect for the pacifist conscience or to combat conscription by any means"

Eva and Esther resigned from the NUWSS over the issue of the First World War and helped establish the Women's Peace Crusade. Other members included Charlotte Despard, Selina Cooper, Margaret Bondfield, Ethel Snowden, Katherine Glasier, Helen Crawfurd, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Mary Barbour.

After Eva's death from cancer on 30th June, 1926. Esther Roper was at her bedside and remarked: "At the end she looked up with that exquisite smile that always lighted up her face when she saw one she loved, then closed her eyes and was at peace." Gore-Booth was buried in St John's Churchyard. Her sister, Constance Markievicz, did not attend the funeral, saying she "simply could not face it all." After her death Roper edited and introduced The Poems of Eva Gore-Booth (1929) and The Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz (1934).

On this day in 1952 Dwight D. Eisenhower resigns as Supreme Allied Commander of NATO in order to campaign in the 1952 United States presidential election. Although Eisenhower had never identified himself with any particular political party, in 1952 he was approached about being the Republican Party candidate for president. He accepted and in November easily defeated the Democratic Party candidate, Adlai Stevenson by 33,936,252 votes to 27,314,922.

On 20th January, 1953 Eisenhower became the first soldier-President since Ulysses Grant (1869-77). Eisenhower left party matters to his vice-president, Richard Nixon. His political philosophy was never clearly defined. He was against enlarging the role of government in economic matters but he did support legislation fixing a minimum wage and the extension of social security. Eisenhower also refused to speak out against Joe McCarthy and members of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) until they began to attack his army commanders in 1954.