On this day on 20th March

On this day in 43 BC, Roman poet Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso) is born in Sulmona, Italy. He studied rhetoric in Rome but decided to abandon his political career and concentrate on writing poetry instead.

Ovid's patron was Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus. Although mainly known for his love poetry, Ovid wrote on a wide range of subjects. His work includes Metamorphoses and The Love Poems.

In AD 8 Ovid upset Emperor Augustus with his poetry and he was banished to Costanta (in modern day Romania). The exact nature of his offence is not known but his poetry indicates that he did not share the same values as Augustus. For example, Ovid's writing concerned the serious crime of adultery, which was punishable by banishment. At the time Augustus was promoting monogamous marriage to increase the population's birth rate.

Ovid died in exile in about AD 17.

On this day in 1616 Sir Walter Raleigh is freed from the Tower of London after 13 years of imprisonment. Raleigh lost his power after the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603. Henry Howard, youngest brother of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, wrote to King James questioning the loyalty of Walter Raleigh. Howard described Raleigh as "an atheist, indiscreet, incompetent, hostile to the very idea of James's succession". It is believed that Howard wrote these letters on behalf of Robert Cecil, who saw Raleigh as a potential rival for the important post of chief government minister.

Walter Raleigh was stripped of his monopolies and captaincy of the guard in May, and was given notice to quit Durham Place, Tobias Matthew, bishop of Durham, having successfully petitioned James for the return of his London home. On 15th July, Raleigh was detained for questioning in connection with a plot to put Arabella Stewart on the throne. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London and on 27th July he tried to stab himself to the heart using a table knife.

Raleigh was tried in November 1603. As a result of an outbreak of plague in London it was decided to hold the trial in the Great Hall of Winchester Castle. According to one source "when Raleigh was escorted from the Tower by a guard of fifty horse, it was touch and go whether he would make it out of the city alive, for the mob was determined to see the disdainful courtier dashed to the ground."

The main evidence against him was the signed confession of Henry Brooke, 11th Baron of Cobham. However, Brooke, withdrew his accusations almost as soon as they were made. Raleigh argued: "Let my accuser come face to face, and be deposed". However, the jury was not told about this and Brooke was not allowed to testify and be cross-examined.

Walter Raleigh was found guilty of treason and sentenced to be hung, drawn and dismembered. However, King James granted him a last-minute reprieve and was ordered to spend the rest of his life confined to the Tower of London. Raleigh was also stripped of all his titles. His letters reveal the depths of his depression and hopelessness during this period. Eventually, he decided to spend his time studying history and science.

Elizabeth Raleigh took a house on Tower Hill and was allowed to make regular visits to see her husband. Their third son, Carew Raleigh, was born in February 1605. Although his health was poor he managed to find the energy to write The History of the World. Raleigh described the book as "the first part of the general history of the world". The first two sections are principally concerned with biblical history, the last three mainly with the story of Greece and Rome. Mark Nicholls has argued: "In the first two God's judgments are seen as the central determinants of events; in the latter three the role of man is more evident."

Walter Raleigh argued that no monarch is above the law of God, or can expect to evade justice. "Throughout history God has intervened to punish or reward the actions of rulers, either directly or on their descendants." Raleigh claimed that the role of the historian was "to teach by example of times past, such wisdom as may guide our desires and actions".

Raleigh Trevelyan has argued that Raleigh is regarded as one of the founders of modern historical writing. "His eye for human interest, his gift for characterization and his own personal observations, from a long and varied experience, make to book far easier to read than most of the prose works of his contemporaries."

The completed manuscript contained about a million words and was licensed to be published in 1611. However, King James did not like the book as he considered it to be "too saucy in censuring princes" and had it suppressed. The agents of George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury, seized copies from the bookshops. This action guaranteeing enormous sales when it came out again two years later. "This book, and Raleigh's other prose works that touched in monarchy and good government, had a profound and catalytic influence on the critics of the Stuart dynasty and on the Parliamentarians who temporarily overthrew it."

The book went through eleven editions in the 17th century, and outsold even Shakespeare's collected works. Oliver Cromwell and John Hampden recommended the book to fellow Puritans. John Milton admitted that he owed Raleigh a great debt and John Locke regarded it as ideal reading for "gentlemen desirous of improving their education".

During his time in prison Raleigh began to outline plans for proposed voyages to the Americas. It has been pointed out that in a eight year period, over half of his letters dealt with this subject. Raleigh was released in March 1616, and at once set about planning his expedition. The planning was, of course, extensive, and little he said or did comforted those at court who were determined on a lasting peace with Spain. He discussed with Sir Francis Bacon, attorney-general, the possibility of seizing Spanish ships carrying treasure. Bacon warned him against this action as it would be an act of piracy.

Historians have dismissed Raleigh's final voyage to the Orinoco River to try to find El Dorado as the hopeless pursuit of fantasy. However, Raleigh appeared certain that his trip would be a financial success. Raleigh's fleet sailed from Plymouth on 12th June 1617, but storms and adverse winds detained it off the southern coast of Ireland for nearly two months. Never comfortable at sea, Raleigh succumbed to fever, and was unable to face solid food for nearly a month. The fleet did not arrive in harbour, at the mouth of the Cayenne River, until 14th November. An expedition under Lawrence Keymis, with Raleigh's nephew George Raleigh in command of the land forces, sailed up the Orinoco in five ships on 10th December.

Carrying provisions for one month, the three vessels that survived the shoals of the delta battled against strong currents and arrived at the settlement San Thomé on 2nd January 1618. Keymis attacked the Spanish outpost in violation of peace treaties with Spain. In the initial attack on the settlement, Raleigh's son, Walter, was fatally shot. Keymis, who broke to Sir Walter the news of his son's death, begged for forgiveness. "Raleigh, fully aware of the implications of these events, confronted him with the bitter statement that Keymis had ruined him by his actions, and refused to support the latter in his report to the English backers. Keymis left Raleigh's cabin, saying that he knew what action to take, and went back to his ship. Raleigh then heard a pistol shot, and sent his servant to enquire what was happening, to which Keymis, lying on his bed, replied that he was just discharging a previously loaded pistol. Half an hour later Keymis's boy entered the cabin and found him dead. The ball had only grazed a rib, and after Raleigh's servant had left he stabbed himself to the heart with a long knife."

Raleigh planned another expedition to discover the El Dorado. He also considered plundering the Spanish treasure fleet. However, his men refused to follow him and the rest of his fleet sailed north leaving Raleigh in his own ship, The Destiny. With a rebellious crew he sailed towards Newfoundland, then across the Atlantic to Ireland. Several members of his crew deserted and Raleigh, with the remnant of his force, sailed on to Plymouth. On his return he wrote to his wife: ‘My brains are broken and tis a torment to me to write… as Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins died heart-broken when they failed of their enterprise, I could willingly die."

Raleigh was placed under arrest by order of Charles Howard of Effingham soon after his landing and conveyed to London by his cousin Sir Lewis Stucley, vice-admiral of Devon and was imprisoned on his arrival on 10th August. Raleigh and the surviving members of his crew were interrogated. On 18th October the commissioners reported their findings to King James. As the evidence against Raleigh was not strong the King issued a warrant for executing the sentence of 1603.

The night before the planned execution Bess was allowed to visit her husband. She told him that she had been given permission to take possession of his corpse and therefore avoiding the terrible tradition of cutting up his body and having it displayed in the city. Raleigh commented: "It is well, dear Bess, that thou may dispose of it dead that had not always the disposing of it when it was alive."

Walter Raleigh was taken to be executed at Whitehall on 29th October 1618. He wore a crisp white ruff, a tawny coloured doublet, a black embroidered waistcoat under it, taffeta breeches, silk stockings, a black velvet gown and a fine pair of shoes. On his finger he had a ring with a diamond that had been given to him by Queen Elizabeth.

Edward Coke, the attorney-general, made a speech about the justice of the punishment: "Sir Walter Raleigh hath been a statesman, and a man who in regard to his parts and quality is to be pitied. He hath been as a star at which the world hath gazed; but stars may fall, nay they must fall when they trouble the sphere in which they abide... You had an honourable trial, and so were justly convicted... You might think it heavy if this were done in cold blood, to call you to execution; but it is not so, for new offences have stirred up his Majesty's justice, to remember to revive what the law hath formerly cast upon you... I know you have been valiant and wise, and I doubt not but you retain both these virtues, for now you shall have occasion to use them. Your faith hath heretofore been questioned, but I am resolved you are a good Christian, for your book, which is an admirable work, cloth testify as much... Fear not death too much, nor fear death too little.... And here I must conclude with my prayers to God for it, and that he would have mercy on your soul."

Walter Raleigh replied: "My honourable good Lords, and the rest of my good friends that come to see me die... As I said, I thank God heartily that he hath brought me into the light to die, and hath not suffered me to die in the dark prison of the Tower, where I have suffered so much adversity and a long sickness. And I thank God that my fever hath not taken me at this time, as I prayed God it might not. But this I say, for a man to call God to witness to a falsehood at any time is a grievous sin... But to call God to witness to a falsehood at the time of death is far more grievous and impious... I do therefore call God to witness, as I hope to see him in his kingdom, which I hope I shall within this quarter of this hour... I did never entertain any conspiracy, nor ever had any plot or intelligence with the French King, nor ever had any advice or practice with the French agent, neither did I ever see the French hand or seal, as some have reported I had a commission from him at sea."

The executioner attempted to place a blindfold on Raleigh. He refused with the words: "Think you I fear the shadow of the axe, when I fear not the axe itself." Raleigh placed his head on the block. The executioner did not react and Raleigh shouted out: "What dost fear? Strike, man, strike!" The executioner took off his head with two blows of his axe. He lifted up the head and showed it on all sides, but could not bring himself to utter the conventional words: "This is the head of a traitor."

Raleigh's head was placed into a red leather bag. The body was covered by his velvet cloak. Both were carried away in Lady Raleigh's mourning coach. Bess wrote to her brother, Nicholas Throckmorton asking him to bury the body in Beddington: "I desire, good brother, that you will be pleased to let me bury the worthy body of my noble husband, Sir Walter Raleigh, in your church at Beddington, where I desire to be buried. The lords have given me his dead body, though they denied me his life. This night he shall be brought you with two or three of my men. Let me hear presently."

However, Nicholas Throckmorton refused to accept the body and he was buried at St Margarets's Church in London. Lady Raleigh had her husband's head embalmed and preserved in its red bag. It was kept in a cupboard and displayed to visitors who revered his memory until her death twenty-nine years later.

On this day in 1856 John Lavery, the son of a failed publican, was born in Belfast. His father was drowned at sea while emigrating to America in 1859. John's mother died soon afterwards and he was brought up by relatives in Ayrshire.

Lavery studied at the Glasgow School of Art as well as in London and Paris. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1886 and soon became a very successful portrait painter. This included a group portrait of the royal family in Buckingham Palace.

In 1917 Charles Masterman, head of the government's War Propaganda Bureau(WPB) recruited Britain's two leading portrait painters, Lavery and William Orpen to paint pictures of British military leaders in France. Unfortunately, soon after receiving the invitation, Lavery had a serious car-crash during a Zeppelin bombing raid.

Unfit to travel to France, Lavery agreed to paint pictures of the Home Front. In 1918 he painted pictures such as A Convoy, North Sea, Army Post Office and The End. After the Armistice he went to France and painted The Cemetery, Etaples (1919).

Lavery was knighted in 1918 and three years later became a RA. Sir John Lavery continued to paint and exhibit at the Royal Academy until his death on 10th January 1941.

On this day in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was published. Harriet Beecher, the daughter of the Congregationalist minister, Lyman Beecher, was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, on 14th June, 1811. Her brother was the famous preacher, Henry Ward Beecher. After an education at the Connecticut Female Seminary she taught at schools in Hartford and Cincinnati.

In 1834 Harriet began to write short stories for the Western Monthly. Two years later she married the Rev. Calvin Ellis Stowe, a clergyman and biblical scholar. Over the next few years Harriet had seven children but continued to write stories and articles for numerous magazines.

Harriet was converted to anti-slavery campaign after hearing Theodore Weld speak at a public meeting. She was determined to do something to help the cause. One day, while in church, she decided to write a novel about slavery. The main character in the book was based on Josiah Henson, an escaped slave whose narrative Harriet had read. Weld's book, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, also provided her with plenty of background material.

Uncle Tom's Cabin was written as a serial and began appearing in the anti-slavery journal, The National Era, in 1851. It was published in book form the following year. In the preface Stowe wrote: "The object of these sketches is to awaken sympathy and feeling for the African race, as they exist among us; to show their wrongs and sorrows, under a system so necessarily cruel and unjust as to defeat and do away with the good effects of all that can be attempted for them by their best friends."

The publisher decided to print 5,000 copies of Uncle Tom's Cabin. It was an immediate best-seller. The first edition sold out in seven days. Despite being banned in the South, over 300,000 copies were sold in its first year. As Frederick Douglass was later to point out: "Its effect was amazing, instantaneous and universal".

Translated into many languages, Uncle Tom's Cabin was also a great success in Europe. In England alone over a million copies were sold. Supporters of slavery were furious and Stowe received hundreds of hostile letters. Thirty pro-slavery novels were published in an attempt to reverse public sympathies in what had now become a propaganda battle. Stowe responded by publishing The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853), a book of source material on slavery.

Stowe visited England where she met Queen Victoria. She also made three tours of Europe and this inspired her book Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands (1854). A second anti-slavery novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp appeared in 1856. The story of a slave rebellion was followed by The Minister's Wooing (1859).

Other books written by Stowe include Agnes of Sorrento (1862), Oldtown Folks (1869) Pink and White Tyranny (1871) and We And Our Neighbours (1875). Harriet Beecher Stowe died on 1st July, 1896.

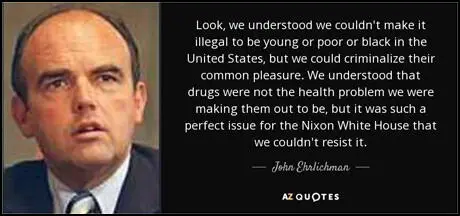

On this day in 1925 John Ehrlichman, was born in Tacoma, Washington. During the Second World War he was a navigator in the 8th Air Force, flying 26 bombing missions over Nazi Germany and receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. He earned a bachelor's degree from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1948 and a law degree from Stanford University in 1951. The following year he became a partner in a Seattle law firm. Later it established a law office in Washington.

In 1960 Ehrlichman joined the campaign staff of Richard Nixon in his fight with John F. Kennedy for the presidency. Ehrlichman was also tour director of Nixon's 1968 campaign. After Nixon's victory, Ehrlichman was appointed presidential counsel. The following year he became presidential assistant for domestic affairs the next year.

Ehrlichman worked closely with Nixon and approved the break-in at the office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg, the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and the Washington Post. He also supervised the “plumbers,” a group whose illegal activities were aimed at stopping White House press leaks and discrediting political opponents of the Nixon administration.

On 3rd July, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested while removing electronic devices from the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. It appeared that the men had been to wiretap the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

The phone number of E.Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were now able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government, that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

In 1972 Nixon was once again selected as the Republican presidential candidate. On 7th November, Nixon easily won the the election with 61 per cent of the popular vote. Soon after the election reports by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post, began to claim that some of Nixon's top officials were involved in organizing the Watergate break-in.

Ehrlichman was involved in the cover-up from the beginning. In April 1973, Nixon forced Ehrlichman and H. R. Haldeman, to resign. A third adviser, John Dean, refused to go and was sacked. On 20th April, Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Richard Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed.

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused but when the Supreme Court ruled against him and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps.

Under extreme pressure, Nixon supplied tapescripts of the missing tapes. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office.

Nixon was granted a pardon but Ehrlichman was charged with obstruction of justice, conspiracy and perjury. At his trial in 1974, Ehrlichman accused Richard Nixon of deceiving him about the cover-up. Ehrlichman was convicted on all charges and sentenced to 20 months to five years in prison. He served 18 months in a minimum-security Arizona prison camp.

In October 1977, Ehrlichman issued a statement where he claimed that while working for Richard Nixon he had "an exaggerated sense of my obligation to do as I was bidden, without exercising independent judgment in the way I might have if it had been an attorney-client relationship.... I went and lied and I'm paying the price for that lack of willpower. I, in effect, I abdicated my moral judgments and turned them over to somebody else."

After his release Ehrlichman lived in New Mexico and wrote the novels, The Company and The China Card. He also published two accounts of his work with Richard Nixon, The Whole Truth (1979) and Witness to Power: The Nixon Years (1982).

In 1991 Ehrlichman moved to Atlanta where he worked as a business consultant for Law Environmental. In 1996, an Atlanta gallery displayed 43 of Ehrlichman's pen-and-ink drawings.

John Ehrlichman died of complications of diabetes in Atlanta, Georgia, on 14th February, 1999.

On this day in 1926 Lord George Curzon died. George Curzon, the eldest son of Baron Curzon, was born on 11th January, 1859. A brilliant student, at Eton College he won a record number of academic prizes before entering Oxford University in 1878. He was elected president of the Oxford Union in 1880 and although he failed to achieve a first he was made a fellow of All Souls College in 1883.

A member of the Conservative Party, Curzon was elected MP for Southport in 1886. It was a safe Tory seat and Curzon neglected his parliamentary duties to travel the world. This material provided the material for Russia in Central Asia (1889), Persia and the Persian Question (1892) and Problems of the Far East (1894).

In November, 1891, Marquis of Salisbury appointed Curzon as his secretary of state for India. Curzon lost office when Earl of Rosebery formed a Liberal Government in 1894.

After the 1895 General Election, the Conservative Party regained power and Curzon was rewarded with the post of under secretary for foreign affairs. Three years later the Marquis of Salisbury granted him the title, Baron Curzon of Kedleston, and appointed him Viceroy of India.

Curzon introduced a series of reforms that upset his civil servants. He also clashed with Lord Kitchener, who became commander-in-chief of the Indian Army, in 1902. Arthur Balfour, the new leader of the Conservative Party, began to have doubts about Curzon and in 1905 he was forced out of office.

Curzon returned to England where he led the campaign against women's suffrage in the House of Lords. In 1908 he helped establish the Anti-Suffrage League and eventually became its president.

In 1916 the new prime minister, David Lloyd George, invited Curzon into his War Cabinet. Curzon served as leader of the House of Lords but refused to support the government's decision to introduce the 1918 Qualification of Women Act. Despite Curzon's objections, it was passed by the Lords by 134 votes to 71.

Curzon was appointed foreign secretary in 1919 and when Andrew Bonar Law resigned as prime minister in May, 1923, Curzon was expected to become the new prime minister. However, the post went to Stanley Baldwin instead. He continued as foreign secretary until retiring from politics in 1924.

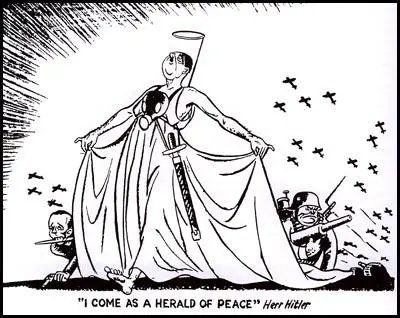

On this day in 1936 cartoonist James Friell criticises Adolf Hitler. Friell, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain and joined its newspaper, The Daily Worker in February 1936.

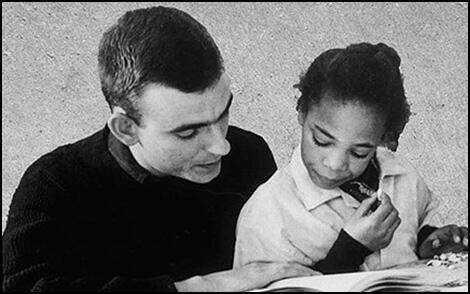

On this day in 1939 Jonathan Daniels, the son of Phillip Brock Daniels, and his wife Constance Weaver, was born in Keene, New Hampshire. He originally intended to join the military but after graduating from the Virginia Military Institute he changed his mind and attended Harvard University.

While at university, in 1962, during an Easter service in Boston, he felt a conviction that he was being called to serve God and applied and was accepted to the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

After the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson in February, 1965, Daniels responded to the plea of Martin Luther King to join the voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama. He attended the Selma to Montgomery protest march.

Daniels remained in the area working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Lowndes County. Daniels helped assemble a list of federal, state, and local agencies that could provide assistance for those in need. He also tutored children, helped poor locals apply for aid, and worked to register voters.

Later that year President Lyndon Baines Johnson attempted to persuade Congress to pass his Voting Rights Act. This proposed legislation removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

Although opposed by politicians from the Deep South, the Voting Rights Act was passed by large majorities in the House of Representatives (333 to 48) and the Senate (77 to 19). The legislation empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

On August 14, 1965, Daniels was one of a group of 29 protesters, including members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who went to Fort Deposit, Alabama, to picket its whites-only stores. All of the protesters were arrested. They were transported in a garbage truck and taken to jail in the nearby town of Hayneville .

After being held for six days the prisoners were released without transport back to Fort Deposit. After release, the group waited near the courthouse jail while one of their members called for transport. Daniels with three others - a white Catholic priest and two black female activists - walked to buy a cold soft drink at nearby Varner's Cash Store, one of the few local places to serve non-whites. Tom L. Coleman, an unpaid special deputy who was holding a shotgun and had a pistol in a holster. Coleman threatened the group and leveled his gun at seventeen-year-old Ruby Sales. Daniels pushed Sales down and caught the full blast of the shotgun. Father Richard F. Morrisroe grabbed activist Joyce Bailey and ran with her. Coleman shot Morrisroe, severely wounding him in the lower back, and then stopped firing. Upon learning of Daniels' murder, Martin Luther King stated that "one of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was performed by Jonathan Daniels."

A grand jury indicted Coleman for manslaughter. Richmond Flowers Sr., the Attorney General of Alabama, believed the charge should have been murder and intervened in the prosecution, but the trial judge T. Werth Thagard decided to continue with the trial. He also refused to wait until Morrisroe had recovered enough to testify and removed Flowers from the case. Coleman claimed self-defense, although Morrisroe and the others were unarmed, and was acquitted of manslaughter charges by an all-white jury. Flowers described the verdict as representing the "democratic process going down the drain of irrationality, bigotry and improper law enforcement."

Father Richard F. Morrisroe was seriously wounded and has never fully recovered, physically, although, after two years of therapy, he was able to walk again. He later recalled: "I'm not sure that the advances in civil rights would have happened without the muscle of the federal government and the tragedy of Jon's death."

Coleman continued working as an engineer for the state highway department. He died at the age of 86 on June 13, 1997, without having faced further prosecution.

On this day in 1940 Archibald Ramsay asked the Minister of Information a question about the New British Broadcasting Service, a radio station broadcasting German propaganda. In doing so he gave full details of the wavelength and the time in the day when it provided programmes. His critics claimed he was trying to give the radio station publicity. Two Labour Party MPs, Ellen Wilkinson and Emanuel Shinwell, made speeches in the House of Commons suggesting that Ramsay was a member of a right-wing secret society.

A member of the Conservative Party, Ramsay was elected to the House of Commons in 1931. Over the next few years he developed extreme right-wing political views. A strongly religious man, he became convinced that the Russian Revolution was the start of an international Communist plot to take over the world. In 1935 two secret agents from Nazi Germany established the anti-Semetic Nordic League. The organization was initially known as the White Knights of Britain or the Hooded Men. Ramsay soon emerged as the leader of this organization. The Nordic League was primarily an upper-middle-class association as opposed to the British Union of Fascists that mainly attracted people from the working class.

On 28th June 1938 Ramsay introduced a Private Member's Bill entitled the "Aliens Restriction (Blasphemy) Bill". The main objective of the legislation was "to prevent the participation by aliens in assemblies for the purpose of propagating blasphemous or atheistic doctrines or in other activities calculated to interfere with the established religious institutions of Great Britain".

Ramsay was now the unofficial leader of the extreme right in Britain. His close associates Admiral Barry Domville, Nesta Webster, Mary Allen, Oswald Mosley, John Becket, William Joyce, A. K. Chesterton, Arthur Bryant, Major-General John Fuller, Thomas Moore, John Moore-Brabazon, and Henry Drummond Wolff.

In the House of Commons Ramsay was the main critic of having Jews in the government. In 1938 he began a campaign to have Leslie Hore-Belisha sacked as Secretary of War. In one speech on 27th April he warned that Hore-Belisha "will lead us to war with our blood-brothers of the Nordic race in order to make way for a Bolshevised Europe."

In May 1939 Ramsay founded a secret society called the Right Club. This was an attempt to unify all the different right-wing groups in Britain. Or in the leader's words of "co-ordinating the work of all the patriotic societies". In his autobiography, The Nameless War, Ramsay argued: "The main object of the Right Club was to oppose and expose the activities of Organized Jewry, in the light of the evidence which came into my possession in 1938. Our first objective was to clear the Conservative Party of Jewish influence, and the character of our membership and meetings were strictly in keeping with this objective."The Daily Worker described Ramsay as "Britain's Number One Jew Baiter".

Members of the Right Club included William Joyce, Anna Wolkoff, Joan Miller, Norah Briscoe, Molly Hiscox, A. K. Chesterton, Francis Yeats-Brown, E. H. Cole, Lord Redesdale, Duke of Wellington, Aubrey Lees, John Stourton, Thomas Hunter, Samuel Chapman, Ernest Bennett, Charles Kerr, John MacKie, James Edmondson, Mavis Tate, Marquess of Graham, Margaret Bothamley, Randolph Stewart, 12th Earl of Galloway and Cecil Serocold Skeels.

Unknown to Ramsay, MI5 agents had infiltrated the Right Club. This included three women, Joan Miller, Marjorie Amor and Helem de Munck. The British government was therefore kept fully informed about the activities of Ramsay and his right-wing friends. Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the government passed a Defence Regulation Order. This legislation gave the Home Secretary the right to imprison without trial anybody he believed likely to "endanger the safety of the realm" On 22nd September, 1939, Oliver C. Gilbert and Victor Rowe, became the first members of the Right Club to be arrested.

In the House of Commons Ramsay attacked this legislation and on 14th December, 1939, asked: "Is this not the first time for a very long time in British history, that British born subjects have been denied every facility for justice?" Ramsay also continued his campaign against Leslie Hore-Belisha and even distributed free copies of right-wing magazines that included articles attacking the Secretary of War. Eventually Neville Chamberlain decided to remove Hore-Belisha as Secretary of State for War and appoint him as Minister of Information. Lord Halifax objected, claiming that it was "inappropriate to have a Jew in charge of publicity." In January 1940 Hore-Belisha was sacked as Secretary of State for War.

By this time Ramsay was being helped in his work by two women, Anna Wolkoff and Joan Miller. Unknown to Ramsay, Miller was a MI5 agent. Wolkoff was the daughter of Admiral Nikolai Wolkoff, the former aide-to-camp to the Nicholas II in London. Wolkoff ran the Russian Tea Room in South Kensington and this eventually became the main meeting place for members of the Right Club.

In the 1930s Anna Wolkoff had meetings with Hans Frank and Rudolf Hess. In 1935 her actions began to be monitored by MI5. Agents warned that Wolkoff had developed a close relationship with Wallis Simpson (the future wife of Edward VIII) and that the two women might be involved in passing state secrets to the German government.

In February 1940, Wolkoff met Tyler Kent, a cypher clerk from the American Embassy. He soon became a regular visitor to the Russian Tea Room where he met other members of the Right Club including Ramsay. Wolkoff, Kent and Ramsay talked about politics and agreed that they all shared the same political views.

Kent was concerned that the American government wanted the United States to join the war against Germany. He said he had evidence of this as he had been making copies of the correspondence between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Kent invited Wolkoff and Ramsay back to his flat to look at these documents. This included secret assurances that the United States would support France if it was invaded by the German Army. Kent later argued that he had shown these documents to Ramsay in the hope that he would pass this information to American politicians hostile to Roosevelt.

On 13th April 1940 Wolkoff went to Kent's flat and made copies of some of these documents. Joan Miller and Marjorie Amor were later to testify that these documents were then passed on to Duco del Monte, Assistant Naval Attaché at the Italian Embassy. Soon afterwards, MI8, the wireless interception service, picked up messages between Rome and Berlin that indicated that Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of German military intelligence (Abwehr), had seen the Roosevelt-Churchill correspondence.

Soon afterwards Anna Wolkoff asked Joan Miller if she would use her contacts at the Italian Embassy to pass a coded letter to William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw) in Germany. The letter contained information that he could use in his broadcasts on Radio Hamburg. Before passing the letter to her contacts, Miller showed it to Maxwell Knight, the head of B5b, a unit within MI5 that conducted the monitoring of political subversion.

On 18th May, Knight told Guy Liddell about the Right Club spy ring. Liddell immediately had a meeting with Joseph Kennedy, the American Ambassador in London. Kennedy agreed to waive Kent's diplomatic immunity and on 20th May, 1940, the Special Branch raided his flat. Inside they found the copies of 1,929 classified documents, including the secret correspondence between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Kent was also found in possession of what became known as Ramsay's Red Book. This book had the names and addresses of members of the Right Club and had been given to Kent for safe keeping.

Anna Wolkoff and Tyler Kent were arrested and charged under the Official Secrets Act. The trial took place in secret and on 7th November 1940, Wolkoff was sentenced to ten years. Kent, because he was an American citizen, was treated less harshly and received only seven years.

Archibald Ramsay was surprisingly not charged with breaking the Official Secrets Act. Instead he was interned under Defence Regulation 18B. Ramsay now joined other right-wing extremists such as Oswald Mosley and Admiral Nikolai Wolkoff in Brixton Prison. Some left-wing politicians in the House of Commons began demanding the publication of Ramsay's Red Book. They suspected that several senior members of the Conservative Party had been members of the Right Club. Some took the view that Ramsay had done some sort of deal in order to prevent him being charged with treason.

Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary refused to reveal the contents of Ramsay's Red Book. He claimed that it was impossible to know if the names in the book were really members of the Right Club. If this was the case, the publication of the book would unfairly smear innocent people.

The government found it difficult to suppress the story and in 1941 the New York Times claimed that Ramsay had been guilty of spying for Nazi Germany: " Before the war he (Ramsay) was strongly anti-Communist, anti-semitic, and pro-Hitler. Though no specific charges were brought against him - Defence Regulations allow that - informed American sources said that he had sent to the German Legation in Dublin treasonable information given to him by Tyler Kent, clerk to the American Embassy in London."

Ramsay sued the owners of the New York Times for libel. In court Ramsay argued that if there had been any evidence of him passing secrets to the Germans he would have been tried under the Official Secrets Act alongside Anna Wolkoff and Tyler Kent in 1940. The newspaper owners were found guilty of libel but the case became a disaster for Ramsay when he was awarded a farthing in damages. As well as the extremely damaging publicity he endured, Ramsay was forced to pay the costs of the case.

Although detained in Brixton Prison he was allowed to submit questions in the House of Commons. This enabled him to continue to make racist comments. For example, on 23rd February, he asked for details of the Jews fighting in the British armed forces. On 3rd August, 1944, he complained about the music of "Oriental and African music" being played on British radio.

During the summer of 1944 several Conservative Party MPs in the House of Commons called for Ramsay to be released from prison. William Gallacher, a member of the Communist Party, argued that he should remain in detention. He pointed out that Ramsay was "a rabid anti-Semite" and that "anti-Semitism is an incitement to murder." He asked "if the mothers of this country, whose lads are being sacrificed now, are to be informed by him that their sacrifices have enabled him to release this unspeakable blackguard." When Gallacher refused to withdraw these comments he was suspended from the House of Commons.

Ramsay was released from Brixton Prison on 26th September, 1944. He was defeated in the 1945 General Election and in 1955 he published his book The Nameless War.

Archibald Ramsay died on 11th March, 1955.