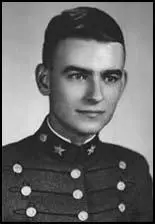

Jonathan Daniels

Jonathan Daniels, the son of Phillip Brock Daniels, and his wife Constance Weaver, was born in Keene, New Hampshire, on 20th March, 1939. He originally intended to join the military but after graduating from the Virginia Military Institute he changed his mind and attended Harvard University.

While at university, in 1962, during an Easter service in Boston, he felt a conviction that he was being called to serve God and applied and was accepted to the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

After the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson in February, 1965, Daniels responded to the plea of Martin Luther King to join the voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama. He attended the Selma to Montgomery protest march.

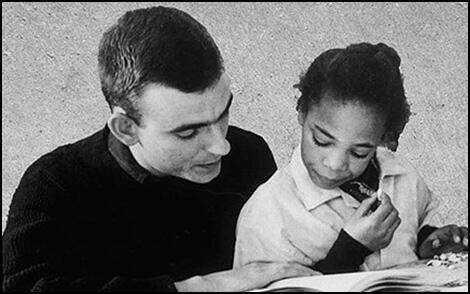

Daniels remained in the area working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Lowndes County. Daniels helped assemble a list of federal, state, and local agencies that could provide assistance for those in need. He also tutored children, helped poor locals apply for aid, and worked to register voters.

Later that year President Lyndon Baines Johnson attempted to persuade Congress to pass his Voting Rights Act. This proposed legislation removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

Although opposed by politicians from the Deep South, the Voting Rights Act was passed by large majorities in the House of Representatives (333 to 48) and the Senate (77 to 19). The legislation empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

On August 14, 1965, Daniels was one of a group of 29 protesters, including members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who went to Fort Deposit, Alabama, to picket its whites-only stores. All of the protesters were arrested. They were transported in a garbage truck and taken to jail in the nearby town of Hayneville .

After being held for six days the prisoners were released without transport back to Fort Deposit. After release, the group waited near the courthouse jail while one of their members called for transport. Daniels with three others - a white Catholic priest and two black female activists - walked to buy a cold soft drink at nearby Varner's Cash Store, one of the few local places to serve non-whites. Tom L. Coleman, an unpaid special deputy who was holding a shotgun and had a pistol in a holster. Coleman threatened the group and leveled his gun at seventeen-year-old Ruby Sales. Daniels pushed Sales down and caught the full blast of the shotgun. Father Richard F. Morrisroe grabbed activist Joyce Bailey and ran with her. Coleman shot Morrisroe, severely wounding him in the lower back, and then stopped firing. Upon learning of Daniels' murder, Martin Luther King stated that "one of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was performed by Jonathan Daniels."

A grand jury indicted Coleman for manslaughter. Richmond Flowers Sr., the Attorney General of Alabama, believed the charge should have been murder and intervened in the prosecution, but the trial judge T. Werth Thagard decided to continue with the trial. He also refused to wait until Morrisroe had recovered enough to testify and removed Flowers from the case. Coleman claimed self-defense, although Morrisroe and the others were unarmed, and was acquitted of manslaughter charges by an all-white jury. Flowers described the verdict as representing the "democratic process going down the drain of irrationality, bigotry and improper law enforcement."

Father Richard F. Morrisroe was seriously wounded and has never fully recovered, physically, although, after two years of therapy, he was able to walk again. He later recalled: "I'm not sure that the advances in civil rights would have happened without the muscle of the federal government and the tragedy of Jon's death."

Coleman continued working as an engineer for the state highway department. He died at the age of 86 on June 13, 1997, without having faced further prosecution.