On this day on 15th December

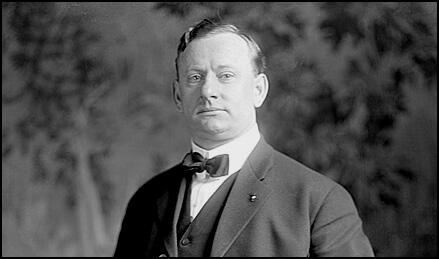

On this day in 1812, Joseph Moses Levy, the son of Moses Levy and Helena Moses, was born. A member of the Jewish faith, Levy, after being educated at Bruce Castle School, was sent to Germany to learn the printing trade. When he returned to England he established a printing company in Shoe Lane, Fleet Street. Levy became involved in the newspaper industry and by 1844 he was chief proprietor of the Sunday Times.

Colonel Arthur Sleigh founded the Daily Telegraph & Courier in June, 1855, Levy agreed to print the newspaper. The venture was not a success and when Sleigh was unable to pay his printing bill, Levy took over the newspaper.

In 1855 there were ten newspapers published in London. The Times, at sevenpence, was the most expensive and had a circulation of 10,000. Its two main rivals, the Daily News and the Morning Post, both cost fivepence. Levy believed that if he could produce a cheaper newspaper than his main competitors, he could expand the size of the overall market.

Levy decided that his son, Edward Levy-Lawson, and Thornton Leigh Hunt, should edit the newspaper. When he re-launched the newspaper on 17th September, 1855, Levy used the slogan, "the largest, best, and cheapest newspaper in the world". Within a few weeks the one penny Daily Telegraph was outselling The Times and by January 1856, Levy was able to announce that circulation had reached 27,000.

The early Daily Telegraph supported the Liberal Party and progressive causes such as the campaign against capital punishment. It also urged reform of the House of Lords and the banning of corporal punishment in the armed forces.

Levy was heavily involved in the production of the Daily Telegraph. As well as managing the newspaper he also wrote theatre and art reviews. Joseph Moses Levy died on 12th October, 1888.

On this day in 1833 Elizabeth Wolstenholme, the daughter of a Methodist minister from Eccles, was born. Elizabeth's brother Joseph received an expensive private education and eventually became professor of mathematics at Cambridge University. The Rev. Wolstenholme held traditional views on girls schooling and Elizabeth only received two years of formal education.

After the death of both her parents, her guardians refused permission for Elizabeth to attend the newly opened, Bedford College for Women. Elizabeth decided to educate herself at home until she gained her inheritance at the age of nineteen. In 1853 Elizabeth purchased her own girls' boarding school in Worsley, Lancashire.

Elizabeth believed that teaching was a highly skilled occupation that needed special training. In 1865 Elizabeth Wolstenholme joined with other women schoolteachers in her area to form the Manchester Schoolmistresses' Association. Two years later Elizabeth and Josephine Butler helped establish the North of England Council for the Higher Education of Women. This organisation provided lectures and examinations for women who wanted to become schoolteachers.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme felt passionate about improving the quality of women's education. In 1869 Josephine Butler asked Elizabeth to contribute an article on education for her book Women's Work and Women's Culture. The article criticised middle class parents for their lack of interest in their daughter's education and set out her plans for a system of high schools for girls in every town in Britain.

In 1864 Parliament passed the Contagious Diseases Act. This act required women suspected of being prostitutes to undergo compulsory medical examination. If the women were suffering from venereal disease they were placed in a locked hospital until cured. Elizabeth Wolstenholme considered this law discriminated against women, as the legislation contained no similar sanctions against men. Elizabeth and Josephine Butler decided to form the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. Elizabeth took the view that it would be impossible to have legislation like this reformed until after women had the vote.

In 1865 eleven women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society . Nine of the eleven women were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. The group included Elizabeth Wolstenholme, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Garrett. At one of the meetings the women discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

The women took their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill added an amendment to the Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men. The amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

In 1868 Elizabeth Wolstenholme became secretary of the Married Women's Property Committee. The main objective was to change the common law doctrine of coverture to include the wife’s right to own, buy and sell her separate property. Elizabeth served alongside Josephine Butler and Richard Pankhurst on the executive committee of the organization.

In the early 1870s Elizabeth became friendly with Benjamin Elmy, a poet from Congleton. The couple lived together and in 1874 she became pregnant. Some members of the Married Women's Property Committee believed that Wolstenholme should resign as they felt the scandal was harming the women's movement. Josephine Butler sent a letter to women leaders defending their behaviour. "They have sinned against no law of Purity. They went through a most solemn ceremony and vow before witnesses. I knew of this true marriage before God - early in 1874. It would have been a legal marriage in Scotland. They blundered; but their whole action was grave and pure. The English marriage laws are impure. English law… sins against the law of purity. It is a species of legal prostitution the woman being the man's property." Lydia Becker was not convinced by these arguments and resigned from the committee.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme, who was pregnant at the time, married Elmy at Kensington Register Office in October 1874. The wedding was a civil ceremony and true to her principals, Elizabeth refused to make a promise of obedience to her husband. She also refused to wear a wedding ring or to give up her surname. Three months after their marriage, Elizabeth gave birth to a son. According to Sylvia Pankhurst, Elmy was, "a stout, sallow man" who "intensely resented and never forgave" the suffragettes for interfering in his affairs. One of her close friends, Harriet McIlquham, later argued that "her life with Mr Elmy has been one of mixed happiness and sorrow... In many ways I believe he has been a great intellectual help to her, and in other ways a great tax on her energies."

Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy was a great believer in presenting petitions to Parliament. She claimed to have personally communicated with 10,000 people and nearly 500,000 leaflets. Her work resulted in the collection of 90,000 signatures demanding changes in the law. The Married Women's Property Committee eventually managed to persuade the House of Commons and the House of Lords to pass the Married Women's Property Act (1882). Another one of her campaigns resulted in the passing of the Custody of Infants Act (1886), which improved the custody rights of mothers.

In 1889 Elizabeth joined Richard Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst and Ursula Bright, to form the Women's Franchise League. Elizabeth, like Richard and Emmeline, was also a member of the Manchester branch of the Independent Labour Party. However, she was constantly in conflict with Bright, who was a member of the Liberal Party. After one dispute with Bright she resigned from the Franchise League and told Harriet McIlquham she did "not intend ever again to take any part whatever in political action on behalf of women.". She did not keep to her pledge and within a year had established another suffrage group, the Women's Emancipation Union.

By the early 1900s Elizabeth had become very critical of what she called the "fiddle-faddling" of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and was one of the first people to join the Women's Social and Political Union. However, Elizabeth was now in her seventies and was not able to take any actions that would result in her going to prison. She wrote: "I am old and hope many mornings that the end may be soon and sudden - and indeed I am so tired in brain, head and body, that I long for rest."

In February 1906, Elizabeth Wolstenholme wrote to a friend that her husband was "too weak to sit up even to have his bed made". Louisa Martindale wrote to Harriet McIlquham asking if she can "manage all the nursing herself?" Benjamin Elmy died the following month.

Elizabeth became concerned about the increasing use of violence by the WSPU. She wrote to the Manchester Guardian in July, 1912: "Now that our cause is on the verge of success, I wish to add my protest against the madness which seems to have seized a few persons whose anti-social and criminal actions would seem designed to wreck the whole movement ... I appeal to our friends in the ministry and in Parliament not to be deterred from setting right a great wrong by the folly or criminality of a few persons." However, unlike other critics of its arson campaign, Elizabeth refused to resign from the WSPU.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy died, aged eighty-four, in a Manchester nursing home on 12th March 1918 after falling down the stairs and hitting her head. Six days earlier, the Qualification of Women Act had been passed by Parliament. The Manchester Guardian reported that she had lived long enough to be told the good news.

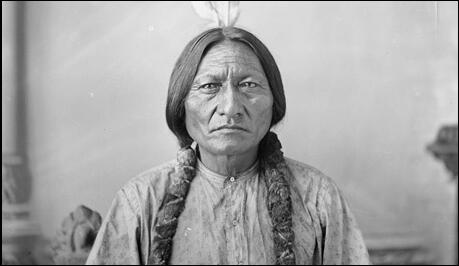

On this day in 1890 Sitting Bull was murdered. Sitting Bull, the son of Four Horn, and a member of the Sioux tribe, was born on Grand River South Dakota, in March, 1834. He hunted at a young age and at 14 took part in a raid on the Crows.

A highly successful warrior, Sitting Bull led a war party against Fort Buford on 24th December, 1866. As well as attacking army patrols Sitting Bull's warriors waged war against the Crow and Shoshone.

In December, 1875 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs directed all Sioux bands to enter reservations by the end of January 1876. Sitting Bull, now a medicine man and spiritual leader of his people, refused to leave his hunting grounds. Crazy Horse agreed and led his warriors north to join up with Sitting Bull.

In June 1876 Sitting Bull subjected himself to a sun dance. This ritual included fasting and self-torture. During the sun dance Sitting Bull saw a vision of a large number of white soldiers falling from the sky upside down. As a result of this vision he predicted that his people were about to enjoy a great victory.

On 17th June 1876, General George Crook and about 1,000 troops, supported by 300 Crow and Shoshone, fought against 1,500 members of the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes. The battle at Rosebud Creek lasted for over six hours. This was the first time that Native Americans had united together to fight in such large numbers.

General George A. Custer and 655 men were sent out to locate the villages of the Sioux and Cheyenne involved in the battle at Rosebud Creek. An encampment was discovered on the 25th June. It was estimated that it contained about 10,000 men, women and children. Custer assumed the numbers were much less than that and instead of waiting for the main army under General Alfred Terry to arrive, he decided to attack the encampment straight away.

Custer divided his men into three groups. Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to explore a range of hills five miles from the village. Major Marcus Reno was to attack the encampment from the upper end whereas Custer decided to strike further downstream.

Reno soon discovered he was outnumbered and retreated to the river. He was later joined by Benteen and his men. Custer continued his attack but was easily defeated by about 4,000 warriors. At the battle of the Little Bighorn Custer and all his 264 men were killed. The soldiers under Reno and Benteen were also attacked and 47 of them were killed before they were rescued by the arrival of General Alfred Terry and his army.

The U.S. army now responded by increasing the number of the soldiers in the area. As a result Sitting Bull and his men fled to Canada, whereas Crazy Horse and his followers surrendered to General George Crook at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska. Crazy Horse was later killed while being held in custody at Fort Robinson.

Sitting Bull was offered an amnesty by the American authorities and in 1881 he agreed to return to Fort Randall, South Dakota, but continued to reject the proposal to sell Sioux lands to the United States government.

In June 1885, Sitting Bull agreed to appear with the Wild West Show run by Buffalo Bill Cody. He was paid $50 a week and also received money for selling signed photographs of himself.

In 1888 Sitting Bull rejected a new offer to sell Sioux land. The American government became increasingly frustrated by Sitting Bull's refusal to negotiate a deal and orders were given for his arrest. On 15th December, 1890, Sitting Bull was killed while being arrested. His son Crow Foot and other followers also lost their lives during this operation.

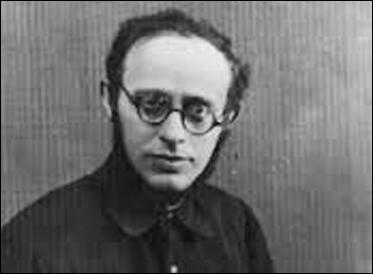

On this day in 1900 Franz Borkenau, the son of a civil servant, was born in Vienna, Austria, on 15th December, 1900. While attending the University of Leipzig he developed an interest in Marxism and joined the German Communist Party (KPD). In 1924, Borkenau moved to Berlin and for a while he served as an official of Comintern. However, he became disillusioned with the way Joseph Stalin treated dissidents and in 1929 he resigned from the KPD.

Borkenau remained a socialist and worked as a researcher for the Institute for Social Research and became associated with what became known as the Frankfurt School. In 1933, the half-Jewish Borkenau fled from Nazi Germany and lived for a time in Paris. Over the next few years Borkenau was involved in organizing support for the Neu Beginnen underground group, which was working for the overthrow of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi government.

Borkenau went to observe the Spanish Civil War and reached Barcelona on August 1936. He larer recalled: "Very few of these armed proletarians wore the new dark-blue pretty militia uniforms. They sat on the benches or walked the pavement of the Ramblas, their rifles over the right shoulder, and often their girls on the left arm... The fact that all these armed men walked about, marched, and drove in their ordinary clothes made the thing only more impressive as a display of the power of the factory workers."

Borkenau met John Cornford who joined the Worker's Party (POUM) army and the two men decided to travel to the front-line together. Cornford was later killed near Lopera on about 27th December 1936. After visiting Valencia and Madrid he returned to Germany.

In January 1937 Borkenau returned to Spain. On his second visit he became critical of the behaviour of Soviet agents in the country. He wrote: "It must be explained, in order to make intelligible the attitude of the communist police, that Trotskyism is an obsession with the communists in Spain. As to real Trotskyism, as embodied in one section of the POUM, it definitely does not deserve the attention it gets, being quite a minor element of Spanish political life. Were it only for the real forces of the Trotskyists, the best thing for the communists to do would certainly be not to talk about them, as nobody else would pay any attention to this small and congenitally sectarian group." Borkenau was denounced as a supporter of Leon Trotsky and was arrested by the Communist Party (PCE).

After his release, Borkenau wrote his highly acclaimed book, The Spanish Cockpit (1937). This was followed by The New German Empire (1939). In the book he argued that Adolf Hitler was intent upon world conquest. Borkenau claimed that the German propaganda campaign for the former African colonies was a "stepping stone to something else". Borkenau argued that the main German target in Africa was South Africa.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Borkenau moved to London, and worked as a writer for various journals, including Horizon, edited by his friend, Cyril Connolly.

In 1947, Franz Borkenau returned to West Germany to work as a professor at the University of Marburg. In June 1950, Borkenau joined forces with John Dewey, Arthur Koestler, Arthur Schlesinger, Bertrand Russell, Ignazio Silone, James Burnham, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Raymond Aron, Alfred Ayer, Benedetto Croce, James T. Farrell, Richard Löwenthal, Melvin J. Lasky and Sidney Hook to established the Congress for Cultural Freedom. It was later revealed that the organisation was funded by the CIA. Franz Borkenau died of a heart-attack on 22nd May 1957.

On this day in 1905 Labour MP, Leslie Solley, was born. He was educated at a London County Council Elementary School and the London University. Solley worked as a research scientist before becoming a barrister.

A member of the Labour Party he was elected to represent Thurrock in the 1945 General Election. In the House of Commons Solley associated with a group of left-wing members that included John Platts-Mills, Konni Zilliacus, Lester Hutchinson, Ian Mikardo, Barbara Castle, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, William Warbey, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin.

In 1947, a group of Labour MPs who were not members of the government, including Leslie Solly, Ian Mikardo, Richard Crossman, Michael Foot, Konni Zilliacus, John Platts-Mills, Lester Hutchinson, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, George Wigg, John Freeman, Richard Acland, William Warbey, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin formed the Keep Left Group. They urged Clement Attlee to develop left-wing policies and were opponents of the cold war policies of the United States and urged a closer relationship with Europe in order to create a "Third Force" in politics.

In April 1948 John Platts-Mills organized a petition in support of Pietro Nenni and the Italian Socialist Party in its general election campaign. He gained support from 27 other MPs including Solley. This went against government policy and Platts-Mills was expelled from the party and Solley was warned about his future conduct.

Ernest Bevin signed the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington on 4th April 1949. Solley completely opposed the treaty arguing that it went against the charter of the United Nations, would accelerate the arms race and make it more difficult to achieve a united Europe. On 12th May, 1949, Solley was only one of only six Labour MPs to vote against the signing of the NATO treaty. Four days later Solley, along with Konni Zilliacus, were expelled from the Labour Party.

Solley unsuccessfully contested Thurrock in the 1950 General Election as an Independent Labour candidate. Solley returned to his work as a lawyer. He was also served as vice-president of the Songwriters Guild of Great Britain. Leslie Solley died on 8th January, 1968.

On this day in 1897 trade union leader, Jacob Liebstein (Jay Lovestone) was born in Hrodna, in modern day Belarus,. The family arrived at Ellis Island on 15th September 1907. From that date Jacob adopted the name Jay Lovestone. His parents set up home in the Lower East Side, but later moved to the Bronx.

As a young man he became a follower of Daniel De Leon. In 1915 he became a student at the City College of New York. Lovestone became friends with Bertram Wolfe and the two men joined the Socialist Party of America and the Intercollegiate Socialist Society.

Lovestone was also a supporter of the Russian Revolution and joined the Communist Propaganda League. Lovestone graduated in June 1918. The following year he began studying at the New York University School of Law. In February 1919, Lovestone joined forces with Bertram Wolfe, John Reed and Benjamin Gitlow to create a left-wing faction in the Socialist Party of America that advocated the policies of the Bolsheviks in Russia.

On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members who supported this faction. The process continued and by the beginning of July two-thirds of the party had been suspended or expelled. This group, including Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Ella Reeve Bloor, Charles Ruthenberg, Rose Pastor Stokes, Claude McKay, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the Communist Party of the United States. By the end of 1919 it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

In 1921, Lovestone became editor of the party newspaper, The Communist, and sat on the editorial board of the The Liberator. Lovestone associated himself with the group led by Charles A. Ruthenberg that favoured a strategy of class warfare. Another group, led by William Z. Foster and James Cannon, believed that their efforts should concentrate on building a radicalised American Federation of Labor.

Lenin died on 21st January 1924. The group led by William Z. Foster believed that Joseph Stalin should become the new leader in the Soviet Union. However, Lovestone's faction supported Nikolay Bukharin. When Stalin emerged as the victor, Lovestone lost a certain amount of influence in the American Communist Party.

It was decided that because William Z. Foster had a strong following in the trade union movement that he should be the party candidate in the 1924 Presidential Election. Foster did not do well and only won 38,669 votes (0.1 of the total vote). This compared badly with the other left-wing candidate, Robert La Follette, of the Progressive Party, who obtained 4,831,706 votes (16.6%).

The Comintern eventually accepted the leadership of Lovestone and Charles Ruthenberg. As Theodore Draper pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "After the Comintern's verdict in favor of Ruthenberg as party leader, the factional storm gradually subsided. Membership meetings throughout the country 'unanimously endorsed' the new leadership and its policies. At the Seventh Plenum at the end of 1926, the Comintern, for the first time in five years, found it unnecessary to appoint an American Commission to deal with an American factional struggle.... Ruthenberg's machine worked so smoothly and efficiently that it made those outside his inner circle increasingly restless. Beneath the surface of the factional lull, another rebellion smoldered, with the helpful encouragement of Cannon, who had touched off the anti-Ruthenberg rebellion three years earlier."

On the death of Charles Ruthenberg in 1927 Lovestone became the party's national secretary. Lovestone, James Cannon and Bertram Wolfe attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928. When Wolfe defended Lovestone against the criticism of Joseph Stalin, he was expelled from the party and was under virtual house arrest in Moscow for six months before he could obtain an exit visa.

While in the Soviet Union James Cannon was given a document written by Leon Trotsky on the rule of Joseph Stalin. Convinced by what he read, when he returned to the United States he criticized the Soviet government. Lovestone gained favour with Stalin by leading the purge of Cannon and his followers. Cannon now joined with other Trotskyists to form the Communist League of America.

By this time Joseph Stalin had placed his supporters in most of the important political positions in the country. Even the combined forces of all the senior Bolsheviks left alive since the Russian Revolution were not enough to pose a serious threat to Stalin.

In 1929 Nikolay Bukharin was deprived of the chairmanship of the Comintern and expelled from the Politburo by Stalin. He was worried that Bukharin had a strong following in the American Communist Party, and at a meeting of the Presidium in Moscow on 14th May he demanded that the party came under the control of the Comintern. He admitted that Jay Lovestone was "a capable and talented comrade," but immediately accused him of employing his capabilities "in factional scandal-mongering, in factional intrigue." Benjamin Gitlow and Ella Reeve Bloor defended Lovestone. This angered Stalin and according to Bertram Wolfe, he got to his feet and shouted: "Who do you think you are? Trotsky defied me. Where is he? Zinoviev defied me. Where is he? Bukharin defied me. Where is he? And you? When you get back to America, nobody will stay with you except your wives." Stalin then went onto warn the Americans that the Russians knew how to handle troublemakers: "There is plenty of room in our cemeteries."

Jay Lovestone realised that he would now be expelled from the American Communist Party. On 15th May, 1929 he sent a cable to Robert Minor and Jacob Stachel and asked them to take control over the party's property and other assets. However, as Theodore Draper has pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "The Comintern beat him to the punch. On May 17, even before the Comintern's Address could reach the United States, the Political Secretariat in Moscow decided to remove Lovestone, Gitlow, and Wolfe from all their leading positions, to purge the Political Committee of all members who refused to submit to the Comintern's decisions, and to warn Lovestone that it would be a gross violation of Comintern discipline to attempt to leave Russia."

William Z. Foster, who had already gone on record as saying, "I am for the Comintern from start to finish. I want to work with the Comintern, and if the Comintern finds itself criss-cross with my opinions, there is only one thing to do and that is to change my opinions to fit the policy of the Comintern", now became the dominant figure in the party.

Lovestone and his supporters, including Benjamin Gitlow, Bertram Wolfe and Charles Zimmerman, now formed a new party the Communist Party (Majority Group). Later it changed its name to the Communist Party (Opposition), the Independent Communist Labor League and finally, in 1938, the Independent Labor League of America. Its journal, The Revolutionary Age, was edited by Wolfe.

Jay Lovestone went to work for the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU). Its leader, David Dubinsky, later arranged for him to work for Homer Martin, the President of the United Auto Workers, who was in conflict with members who he accused of being members of the American Communist Party. This strategy did not work and Martin was eventually ousted from power.

In 1943 Lovestone became the director of the ILGWU's International Affairs Department. The following year David Dubinsky arranged for Lovestone to join the AFL's Free Trade Union Committee. He was also active in the American Institute for Free Labor Development, an organization sponsored by the American Federation of Labor. Later it also received secret payments from the CIA. This began a long-term friendship with James Jesus Angleton, Director of Operations for Counter-Intelligence.

In 1963 Lovestone became director of the AFL-CIO's International Affairs Department (IAD), which arranged for millions of dollars from the CIA to aid anti-communist activities internationally, particularly in Latin America. The AFL-CIO president George Meany discovered in 1964 that Lovestone was involved with the CIA and instructed him to break-off contact with James Jesus Angleton. Lovestone agreed to do this but when Meany discovered in 1974 that he was still working with Angleton he forced him from office. Jay Lovestone died on 7th March, 1990.

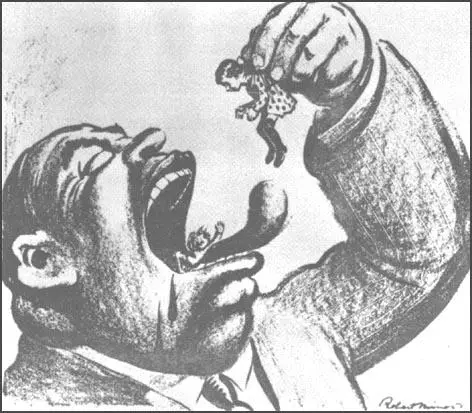

On this day in 1910, Mary Frances Earl makes a statement on how the police treated women demonstrators. Emmeline Pankhurst, led 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons on 18th November, 1910. Sylvia Pankhurst was one of the women who took part in the protest and experienced the violent way the police dealt with the women: "I saw Ada Wright knocked down a dozen times in succession. A tall man with a silk hat fought to protect her as she lay on the ground, but a group of policemen thrust him away, seized her again, hurled her into the crowd and felled her again as she turned. Later I saw her lying against the wall of the House of Lords, with a group of anxious women kneeling round her. Two girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two uniformed policemen. One of a group of officers in plain clothes ran up and kicked one of the girls, whilst the others laughed and jeered at her."

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel."

On this day in 1914 Millicent Fawcett wrote about a possible women's peace movement. With growing political tension growing between Britain and Germany, Fawcett issued a statement on behalf of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. "We, the women of the world, view with apprehension and dismay the present situation in Europe, which threatens to involve one continent, if not the whole world, in the disasters and horrors of war... We women of twenty-six countries, having bonded ourselves together in the International Woman Suffrage Alliance with the object of obtaining the political means of sharing with men the power which shapes the fate of nations, appeal to you to leave untried no method of conciliation or arbitration for arranging international differences to avert deluging half the civilised world in blood."

Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, the NUWSS declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. That night Millicent Fawcett chaired a meeting against the war. Speakers included Helena Swanwick, Olive Schreiner, Mary Macarthur, Mabel Stobart and Elizabeth Cadbury. Fawcett said there were millions of women who thought that was was a "crime against society". She added: "A way must be found out of the tangle... In the first place they should try and avoid bitterness of national feeling. They should on the one hand keep down panic and on the other the war fever and Jingo feeling."

Although Fawcett supported the war effort she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

However, Fawcett refused to join the International Women's Peace Party. She told Carrie Chapman Catt on 15th December 1914, "I am strongly opposed to the above proposal, mainly for the reason that women are as subject as men are to national prepossessions and susceptibilities and it would hardly be possible to bring together the women of the belligerent countries without violent outbursts of anger and mutual recriminations. We should then run the risk of the scandal of a Peace Congress disturbed and perhaps broken up by violent quarrels and fierce denunciations. It is true this often takes place at Socialist and other international meetings: but it is of less importance there: no one expects the general run of men to be anything but fighters. But a Peace Congress of Women dissolved by violent quarrels would be the laughing stock of the world". .

On this day in 1950, campaigner against child labour, Josephine Goldmark died. Goldmark was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 13th October, 1877. After graduating from Bryn Mawr College she became research director of the National Consumer's League (NCL) where she worked closely with Florence Kelley. After serving as publications secretary she was promoted to chairman of the NCL's committee on legal defence of labour laws.

Goldmark's research was published in several books including Child Labor Legislation Handbook (1907), Fatigue and Efficiency (1912), The Case for the Shorter Work Day (1916) and The Case Against Nightwork for Women (1918).

In 1919 Goldmark was appointed principal investigator of the Committee for the Study of Nursing Education. The publication of her report, Nursing and Nursing Education in the United States (1923) resulted in the improvement of nursing education in the United States.

After leaving the Committee for the Study of Nursing Education she joined Florence Kelley in her campaign to improve the working conditions of industrial workers.

On this day in 1957 civil rights activist Leonidas Dyer died. Dyer was born in Warren Country, Missouri, on 11th June, 1871. After attending Central Wesleyan College and Washington University he was admitted to the bar in 1893. He practiced law in St. Louis, Missouri before serving in the Spanish-American War.

Dyer, a member of the Republican Party, was elected to Congress in 1911. He was defeated in 1914 but returned to Congress in 1915. A strong opponent of racial intolerance, Dyer made several unsuccessful attempts to persuade Congress to pass a federal anti-lynching law.

After eighteen years in Congress Dyer was defeated in 1933. Two attempts to return to Congress in 1934 and 1936 ended in failure. Leonidas Dyer, who returned to his law practice, died in St. Louis on 15th December, 1957.