On this day on 10th September

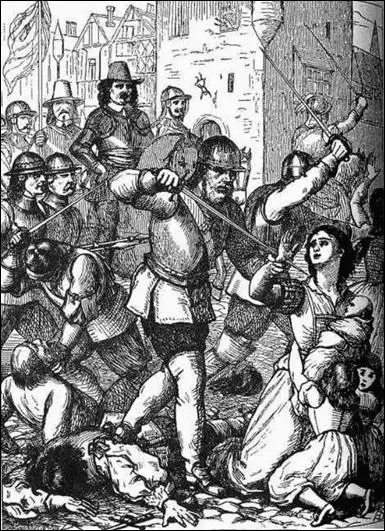

On this day in 1649 Oliver Cromwell calls on the governor of Drogheda to surrender. Cromwell was asked by Parliament to take control of Ireland. The country had caused serious problems for English generals in the past so Cromwell was careful to make painstaking preparations before he left. Cromwell ensured that the wage arrears of his army were paid, and that he was guaranteed sufficient financial provision by parliament. On 15th August 1649, Cromwell arrived in Ireland and took control of an army of 12,000 men. (74) Cromwell made a speech to the Irish people the following day: "God has brought us here in safety... We are here to carry on the great work against the barbarous and blood-thirsty Irish... to propagate the Gospel of Christ and the establishment of truth... and to restore this nation to its former happiness and tranquility."

Cromwell, like nearly all Puritans "had been inflamed against the Irish Catholics by the true and false allegations of the atrocities which they had committed against English Protestants settlers during the Irish Catholic rebellion of 1641." He wrote at the time that "all the world knows their barbarism". Even the philosopher, Francis Bacon, and the poet John Milton, who "believed passionately in liberty and human dignity", shared the view that "the Irish were culturally so inferior that their subordination was natural and necessary."

Cromwell's first action on reaching Ireland was to forbid any plunder or pillage - an order that could not have been enforced with an unpaid army. Two men were hanged for plundering to convince the soldiers he was serious about this order. To control Dublin's northern approaches Cromwell needed to take the port of Drogheda. Once in his hands he could feel confident of controlling the whole of the northern route from Dublin to Londonderry. On 3rd September, around 12,000 men and supporting vessels had arrived outside the town. Surrounding the whole town was a massive wall, 22 feet high and 6 feet thick.

Sir Arthur Aston, who had been fighting for the royalists during the English Civil War, was the governor of Drogheda. On 10th September, Cromwell advised Aston to surrender. "I have brought the army belonging to the Parliament of England to this place, to reduce it to obedience... if you surrender you will avoid the loss of blood... If you refuse... you will have no cause to blame me."

Oliver Cromwell had four times as many men as Aston and was better supplied with weapons, stores and equipment. Cromwell's proposal was rejected and the garrison opened fire with what weapons they had. Cromwell's reply was to attack the city wall and by nightfall two breaches had been made. The following day Cromwell led his soldiers into Drogheda.

Aston and some 300 soldiers climbed Mill Mount. Cromwell's troops surrounded the men and it was usually the custom to allow them to surrender. However, Cromwell gave the order to kill them all. Aston's head was beaten in with his own wooden leg. Cromwell instructed his men to kill all the soldiers in the town. About eighty men had taken refuge in St Peter's Church. It was set on fire and all the men were killed. All the priests that were captured were also slaughtered.

Cromwell sent a letter to William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons: "I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbued their hands in so much innocent blood; and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are the satisfactory grounds for such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret."

On this day in 1676 Gerrard Winstanley died.

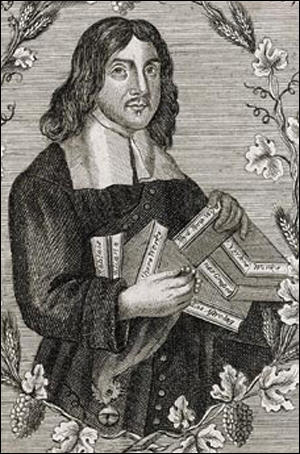

Gerrard Winstanley, the son of a mercer, was born in Wigan in October, 1609. There is no evidence that the family was of anything but modest standing in the parish. It is frequently assumed that Winstanley attended the local grammar school but no enrolment records for the period are extant.

Winstanley's family was involved in the cloth trade. At the time the town was known as a centre of the woollen and linen manufacture, drawing both on local supplies and imports of linen flax from Ireland. Many of its inhabitants were also becoming involved with new branches of manufacture, especially cotton.

On 19th April 1630, when he was 20 years old, he was apprenticed to Sarah Gater, who ran a cloth business in the London parish of St Michael Cornhill. He took a keen interest in religion and was described as "a good Christian, and a godly man."

By 1638 he was admitted a freeman of the Merchant Taylors' Company and by the following year had established his own household in the parish of St Olave Jewry where he was involved in the business of buying and selling textiles on credit.

In September 1640 Winstanley married the 27-year-old Susan King. She came from a medical family. Her mother was a midwife and her father, William King, was a prominent surgeon, and two of her sisters had married surgeons earlier the same year.

On 4 January 1642, Charles I sent his soldiers to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers). His opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads) and it was the beginning of the English Civil War. The Roundheads immediately took control of London.

Gerrard Winstanley was a "vigorous supporter of parliament" but the war had a bad impact on his business. Several merchants, including Philip Peake and Matthew Backhouse, were unable to pay money they owed Winstanley. In the autumn of 1643 he vacated his house and shop in London and moved to Cobham. He later wrote: "the burdens of and for the soldiery in the beginning of the war, I was beaten out of both estate and trade, and forced to accept the good-will of friends, crediting of me, to live a country life."

Winstanley explained that he was no longer willing to work in the cloth trade. "For matter of buying and selling, the earth stinks with such unrighteousness, that for my part, though I as bred a tradesman, yet it is so hard a thing to pick out a poor living, that a man shall sooner be cheated of his bread, then get bread by trading among men, if by plain dealing he put trust in any."

Only a small number of those who opposed the king in the English Civil War were committed republicans and few of those who took part in these events would have considered themselves revolutionaries. However, some of those fighting did want to change society. In 1645 John Lilburne, John Wildman, Richard Overton and William Walwyn formed a new political party called the Levellers. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%.

It has been claimed that the ideas of people like Lilburne, Wildman, Overton and Walwyn, had an impact on Winstanley. It is also believed that another source of inspiration was the work of John Foxe. However, David Petegorsky, has argued that "to search for the sources of Winstanley's theological conceptions would be as futile as to attempt to identify the streams that have contributed to the bucket of water one has drawn from the sea."

During the war life was hard for people living in Cobham. Most people living in the village were landless labourers and the area was dominated by a few entrepreneurial yeomen farmers and gentry. Winstanley was one of the more prosperous farmers but he had sympathy for the poor. On 10th April 1646 Winstanley, with five other men and two women, was fined at Cobham manorial court for digging on waste land and taking peat and turf. According to J. D. Alsop "this was probably a symbolic protest by manorial tenants, four of whom were local office holders".

Gerrard Winstanley published four pamphlets in 1648. These were highly critical of religious leaders who "hold forth God and Christ to be at a distance from men" or think that "God is in the Heavens above the skies". Winstanley argued that God is "the spirit within you". Winstanley then went on to describe God "doth not preserve one creature and destroy another... but he hath a regard to the whole creation; and knits every creature together into oneness; making every creature to be an upholder of his fellow; and so every one is an assistant to preserve the whole."

In October 1648 Winstanley's friend William Everard was arrested. It was reported that he held blasphemous opinions "as to deny God, and Christ, and Scriptures, and prayer". His arrest prompted Winstanley to publish Truth Lifting up the Head above Scandals (1648), in which he asked who has the authority to restrain religious differences? He argued that Scripture, on which traditionally authority rested, was unsafe because there were no undisputed texts, translations, or interpretations. Winstanley concluded that authority should be based in the spirit. "All people carried the spirit, and thus their own authority, within them. The academics and clergy were following their own imaginations rather than the spirit and... must be seen as false prophets".

Gerrard Winstanley gradually became more radical and he began arguing that all land belonged to the community rather than to separate individuals. In January, 1649, he published the The New Law of Righteousness. In the pamphlet he wrote: "In the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another."

Winstanley claimed that the scriptures threatened "misery to rich men" and that they "shall be turned out of all, and their riches given to a people that will bring forth better fruit, and such as they have oppressed shall inherit the land." He did not only blame the wealthy for this situation. As John Gurney has pointed out, Winstanley argued: "The poor should not just be seen as an object of pity, for the part they played in upholding the curse had also to be addressed. Private property, and the poverty, inequality and exploitation attendant upon it, was, like the corruption of religion, kept in being not only by the rich but also by those who worked for them."

Winstanley claimed that God would punish the poor if they did not take action: "Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men, your oppressors by your labours... If you labour the earth, and work for others that live at ease, and follows the ways of the flesh by your labours, eating the bread which you get by the sweat of your brows, not their own. Know this, that the hand of the Lord shall break out upon such hireling labourer, and you shall perish with the covetous rich man."

On Sunday 1st April, 1649, Winstanley, William Everard, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them.

The men sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". Research shows that new people joined the community over the next few months. Most of these were local inhabitants. These men became known as Diggers.

John Gurney has argued that "Everard's flamboyant character and his preference for confrontation over presentation helped to ensure that in the early days of the digging he was more quickly noticed than the more self-effacing Winstanley, and many observers assumed that it was he, rather than Winstanley, who was the real leader of the Diggers".

According to Peter Ackroyd, Everard proclaimed in a vision by God to "dig and plough the land" and that the Diggers believed in a form of "agrarian communism" and that that it was time for the English to free themselves from the the tyranny of Norman landlords and to make "the earth a common treasury for all."

Laurence Clarkson claimed that he had supported the ideas of Winstanley and had spent some time digging on the commons. However, Winstanley strongly disapproved of Clarkson's sexual ideas and condemned the "Ranting crew" and he warned fellow Diggers to steer clear of "lust of the flesh" and "the practise of Ranting".

Winstanley announced his intentions in a manifesto entitled The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649). It opened with the words: "In the beginning of time, the great Creator Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, to preserve Beasts, Birds, Fishes, and Man, the lord that was to govern this Creation; for Man had Domination given to him, over the Beasts, Birds, and Fishes; but not one word was spoken in the beginning, that one branch of mankind should rule over another."

Gerrard Winstanley argued for a society without money or wages: "The earth is to be planted and the fruits reaped and carried into barns and storehouses by the assistance of every family. And if any man or family want corn or other provision, they may go to the storehouses and fetch without money. If they want a horse to ride, go into the fields in summer, or to the common stables in winter, and receive one from the keepers, and when your journey is performed, bring him where you had him, without money."

Digger groups also took over land in Kent (Cox Hill), Buckinghamshire (Iver) and Northamptonshire (Wellingborough). A. L. Morton has argued that Winstanley and his followers used the argument that William the Conqueror had "turned the English out of their birthrights; and compelled them for necessity to be servants to him and to his Norman soldiers." Winstanley responded to this situation by advocating what Morton describes as "primitive communism".

Winstanley's writings suggested that he shared the view held by the Anabaptists that all institutions were by their nature corrupt: "nature tells us that if water stands long it corrupts; whereas running water keeps sweet and is fit for common use". To prevent power corrupting individuals he advocated that all officials should be elected every year. "When public officers remain long in place of judicature they will degenerate from the bounds of humility, honesty and tender care of brethren, in regard the heart of man is so subject to be overspread with the clouds of covetousness, pride, vain glory."

Local landowners were very disturbed by these developments. According to one historian, John F. Harrison: "They were repeatedly attacked and beaten; their crops were uprooted, their tools destroyed, and their rough houses." Oliver Cromwell also condemned the actions of the Diggers: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces."

On 16th April 1649, Henry Saunders, a yeoman of the parish, complained to the council of state about the growing number of Diggers, now "between 20 and 30". A report was sent to General Thomas Fairfax, the commander of the army, stating that "although the pretence of their being there by them avowed may seem very ridiculous, yet that conflux of people may be a beginning whence things of a greater and more dangerous consequence may grow to this disturbance of the peace and quiet of the Commonwealth." It suggested that Fairfax should send some troops to disperse the Diggers and prevent them from returning to St George's Hill.

General Fairfax sent Captain John Gladman was sent to St George's Hill and found only four men digging. The camp had already been dealt with by local inhabitants: "They have digged in all about an acre of land, but it is trampled down by the country people, who would not suffer them to dig one day more."

On 20th April, Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, appeared before General Fairfax in London. Both men, because of their political beliefs, refused to remove their hats in the presence of the General. Everard told Fairfax that since the Norman Conquest, England had lived under a tyranny. He assured Fairfax that he and his fellows did not intend either to interfere with private property or to destroy enclosures, but that they were merely claiming the commons which were the rightful possession of the poor. The two men made it clear that they intended to cultivate the wastelands in common and to provide sustenance for the distressed."

Gerrard Winstanley wrote to General Fairfax in June 1649 explaining his objectives: "And the truth is, experience shows us, that in this work of Community in the earth, and in the fruits of the earth, is seen plainly a pitched battle between the Lamb and the Dragon, between the Spirit of love, humility and righteousness... and the power of envy, pride, and unrighteousness ... the latter power striving to hold the Creation under slavery, and to lock and hide the glory thereof from man: the former power labouring to deliver Creation from slavery, to unfold the secrets of it to the sons of man, and so to manifest himself to be the great restorer of all things."

Winstanley continued his experiment and on 1st June he published A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, that was signed by 44 people. It stated that while waiting for their first crop yields, they proposed to sell wood from the commons in order to buy food, ploughs, carts, and corn. No threat would be made to private property, but "the promises of reformation and liberation made from the solemn league and covenant through to the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords must be honoured".

Instructions were given for the Diggers to be beaten up and for their houses, crops and tools to be destroyed. These tactics were successful and within a year all the Digger communities in England had been wiped out. A number of Diggers were indicted at the Surrey quarter sessions and five were imprisoned for just over a month in the White Lion prison in Southwark.

Despite the hostility Winstanley's experiment continued and in January 1650 "having put my arm as far as my strength will go to advance righteousness: I have writ, I have acted, I have peace: and now I must wait to see the spirit do his own work in the hearts of others, and whether England shall be the first land, or some other, wherein truth shall sit down in triumph."

On 19th April, 1650, a group of local landowners, including John Platt, Thomas Sutton, William Starr and William Davy, with several hired men, destroyed the Digger community in Cobham: "They set fire to six houses, and burned them down, and burned likewise some of the household stuff... not pitying the cries of many little children, and their frightened mothers.... they kicked a poor man's wife, so that she miscarried her child."

Gerrard Winstanley returned to farming his own land. The historian, Alfred Leslie Rowse, quoted one source that claimed he had made a "most shameful retreat from George's Hill, with a spirit of pretended universality, to become a real tithe-gather of propriety". Rowse harshly argues that "Winstanley was no better than the rest of the Saints - out of his own ends."

Winstanley's best-known work, The Law of Freedom, was published in February 1652 after twenty months of silence following the collapse of the digging experiments. It appears to have been an attempt to enlist the power and influence of Oliver Cromwell. And now you have the power of the land in your hand, you must do one of these two things. First, either set the land free to the oppressed commoners, who assisted you, and paid the Army their wages; and then you will fulfil the Scriptures and your own engagements, and so take possession of your deserved honour. Or secondly, you must only remove the Conqueror's power out of the King's hand into other men's, maintaining the old laws still."

Winstanley urged Cromwell not to establish a dictatorship: "For you (Cromwell) must either establish Commonwealth's freedom in power, making provision for every one's peace, which is righteousness, or else you must set up Monarchy again. Monarchy is twofold, either for one king to reign or for many to reign by kingly promotion. And if either one king rules or many rule by king's principles, much murmuring, grudges, trouble and quarrels may and will arise among the oppressed people on every gained opportunity."

Marxist writers in the 19th century such as Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky have claimed that in this pamphlet Winstanley had provided a complete framework for a socialist order. John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) has pointed out: "Winstanley has an honoured place in the pantheon of the Left as a pioneer communist. In the history of the common people he is also representative of that other minority tradition of popular religious radicalism, which, although it reached a crescendo during the Interregnum, had existed since the Middle Ages and was to continue into modern times. Totally opposed to the established church and also separate from (yet at times overlapping) orthodox puritanism, was a third culture which was lower-class and heretical. At its centre was a belief in the direct relationship between God and man, without the need of any institution or formal rites. Emphasis was on an inner spiritual experience and obedience to the voice of God within each man and woman."

In about 1555 Winstanley became active in the Society of Friends (Quakers), a religious group established by George Fox. It was later claimed by Thomas Tenison, that Winstanley was the true originator of the principles of Quakerism. Lewis H. Berens suggested that the similarities between Winstanley's ideas and those of the Quakers were too great to be wholly coincidental. However, William C. Braithwaite, while accepting the similarities between the ideas of Winstanley and Fox, felt the Digger and the founder of Quakerism were most likely to be "independent products of the peculiar social and spiritual climate of the age."

In 1657 Winstanley was given extra land by his father-in-law, William King. When he heard the news Laurence Clarkson attacked him for "a most shameful retreat from Georges-hill… to become a real Tithe-gatherer of propriety." After the death of his first wife, Susan Winstanley in 1664 he married Elizabeth Stanley. They had a son (baptized Gerrard in 1665) and subsequently a daughter and a second son. In 1667 and 1668 Winstanley served as a churchwarden.

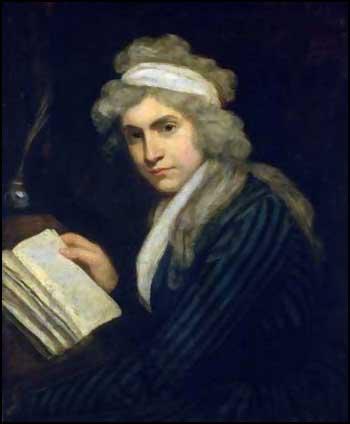

On this day in 1797 Mary Wollstonecraft died. Mary's daughter, Mary, was born. The baby was healthy but the placenta was retained in the womb. The doctor's attempt to remove the placenta resulted in blood poisoning and Mary Wollstonecraft died.

Mary Wollstonecraft, the eldest daughter of Edward Wollstonecraft and Elizabeth Dixon Wollstonecraft, was born in Spitalfields, London on 27th April 1759. At the time of her birth, Wollstonecraft's family was fairly prosperous: her paternal grandfather owned a successful Spitalfields silk weaving business and her mother's father was a wine merchant in Ireland.

Mary did not have a happy childhood. Claire Tomalin, the author of The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (1974) has pointed out: "Mary's father was sporadically affectionate, occasionally violent, more interested in sport than work, and not to be relied on for anything, least of all for loving attention. Her mother was indolent by nature and made a darling of her first-born, Ned, two years older than Mary; by the time the little girl had learned to walk in jealous pursuit of this loving pair, a third baby was on the way. A sense of grievance may have been her most important endowment."

In 1765 her grandfather died and her father, his only son, inherited a large share of the family business. He sold the business and purchased a farm at Epping. However, her father had no talent for farming. According to Mary, he was a bully, who abused his wife and children after heavy drinking sessions. She later recalled that she often had to intervene to protect her mother from her father's drunken violence. William Godwin claims this had a major impact on the development of her personality as Mary "was not formed to be the contented and unresisting subject of a despot".

Mary had several younger brothers and sisters: Henry (1761), Eliza (1763), Everina (1765), James (1768) and Charles (1770). When she was nine years of age, the family moved to a farm in Beverley where Mary received a couple years at the local school, where she learned to read and write. It was the only formal schooling she was to receive. Ned, on the other hand, received a good education, with the hope that eventually he would become a lawyer. Mary was upset by the amount of attention Ned received and said of her mother "in comparison with her affection for him, she might be said not to love the rest of her children".

In 1673 Mary became friends with another fourteen-year-old, girl, Jane Arden. Her father, John Arden, was a highly educated man who gave public lectures on natural philosophy and literature. Arden also gave lessons to his daughter and her new friend. "Sensitive about the failings she was beginning to perceive in her own family, and contrasting them with the dignified, sober and well-read Ardens, Mary envied Jane her entire situation and attached herself determinedly to the family."

Mary and Jane had a argument and stopped seeing each other. However, they did keep in contact by letter: "Before I begin I beg pardon for the freedom of my style. If I did not love you I should not write so; I have a heart that scorns disguise, and a countenance which will not dissemble: I have formed romantic notions of friendship. I have been once disappointed - I think if I am a second time I shall only want some infidelity in a love affair, to qualify me for an old maid, as then I shall have no idea of either of them. I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have the first place or none. - I own your behaviour is more according to the opinion of the world, but I would break such narrow bounds"

In 1774 Edward Wollstonecraft's financial situation forced the family to move again. This time they returned to a house in Hoxton. Her brother, Ned, was being trained as a lawyer, and used to come home at weekends. Mary continued to have a bad relationship with her brother and constantly undermined her confidence. She later recalled that he took "particular pleasure in tormenting and humbling me".

While in London she met Fanny Blood. "She was conducted to the door of a small house, but furnished with peculiar neatness and propriety. The first object that caught her sight, was a young woman of slender and elegant form... busily employed in feeding and managing some children, born of the same parents, but considerably her inferior in age. The impression Mary received from this spectacle was indelible; and before the interview was concluded, she had taken, in her heart, the vows of eternal friendship."

Mary identified closely with her new friend: "Fanny was eighteen to Mary's sixteen, slim and pretty and set apart from the rest of her family by her manners and talents. Mary could see in her a mirror-image of herself: an eldest daughter, superior to her surroundings, often in charge of a brood of little ones, with an improvident and a drunken father and a mother charming and gentle but quite broken in spirit."

After two years in London the family moved to Laugharne in Wales but Mary continued to correspond with Fanny, who had been promised in marriage to Hugh Skeys, who was living in Lisbon. Mary said in one letter that her feeling for her "resembled a passion" and was "almost (but not quite) that of an intending husband". Mary explained to Jane Arden that her relationship with Fanny was difficult to explain: "I know my resolution may appear a little extra-ordinary, but in forming it I follow the dictates of reason as well as the bent of my inclination."

Mary's mother died in 1782. She now went to live with Fanny Blood and her parents at Waltham Green. Her sister Eliza, married Meredith Bishop, a boat-builder from Bermondsey. In August, 1783, after the birth of her first child, she suffered a mental breakdown and Mary was asked to look after her. When she arrived at her sister's home Mary found Eliza in a very disturbed state. Eliza explained that she had "been very ill-used by her husband".

Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, explaining that "Bishop cannot behave properly - and those who attempt to reason with him must be mad or have very little observation... My heart is almost broken with listening to Bishop while he reasons the case. I cannot insult him with advice which he would never have wanted if he was capable of attending to it." In January, 1784, the two sisters escaped from Bishop and went to live under a false name in Hackney.

A few months later Mary Wollstonecraft opened a school in Newington Green, with her sister Eliza and a friend, Fanny Blood. Soon after arriving in the village, Mary made friends with Richard Price, a minister at the local Dissenting Chapel. Price and his friend, Joseph Priestley, were the leaders of a group of men known as Rational Dissenters. Price told her that the "love of God meant attacking injustice".

Price had written several books including the very influential Review of the Principal Questions of Morals (1758) where he argued that individual conscience and reason should be used when making moral choices. Price also rejected the traditional Christian ideas of original sin and eternal punishment. As a result of these religious views, some Anglicans accused Rational Dissenters of being atheists.

In January 1784, Fanny Blood travelled to Lisbon to marry Hugh Skeys. Mary missed her deeply and wrote that "without someone to love the world is a desert". She confessed that "my heart sometimes overflows with tenderness - and at other times seems quite exhausted and incapable of being warmly interested about anyone." She was attracted to John Hewlett, a young schoolmaster, and was very upset when he married another woman.

Fanny Blood became seriously ill and Mary decided to visit her in Portugal. When she arrived she discovered that Fanny was nine-months pregnant. She successfully gave birth but within days both Fanny and the child were dead. Mary stayed on in Lisbon for several weeks. She and Skeys were drawn together in their grief but she had to return to her school and returned to England in February 1786.

Wollstonecraft argued that friendship was more important than love: "Friendship is a serious affection; the most sublime of all affections, because it is founded on principle, and cemented by time. The very reverse may be said of love. In a great degree, love and friendship cannot subsist in the same bosom; even when inspired by different objects they weaken or destroy each other, and for the same object can only be felt in succession. The vain fears and fond jealousies, the winds which fan the flame of love, when judiciously or artfully tempered, are both incompatible with the tender confidence and sincere respect of friendship".

Although Mary was brought up as an Anglican, she soon began attending Price's Unitarian Chapel. Price held radical political views and had encountered a great deal of hostility when he supported the cause of American independence. At Price's home Mary Wollstonecraft met other leading radicals including the publisher, Joseph Johnson. He was impressed by Mary's ideas on education and commissioned her to write a book on the subject. In Thoughts on the Education of Girls, published in 1786, Mary attacked traditional teaching methods and suggested new topics that should be studied by girls.

Mary Wollstonecraft became emotionally involved with the artist Henry Fuseli. He had made a living from producing pornographic drawings and eventually gained fame for his painting The Nightmare, that showed a sleeping woman, head and shoulders dropped back over the end of her couch. She is surmounted by an incubus that peers out at the viewer. Contemporary critics were taken aback by the overt sexuality of the painting.

Fuseli was forty-seven and Mary twenty-nine. He was recently married to his former model, Sophia Rawlins. Fuseli shocked his friends by constantly talking about sex. Mary later told William Godwin that she never had a physical relationship with Fuseli but she did enjoy "the endearments of personal intercourse and a reciprocation of kindness, without departing in the smallest degree from the rules she prescribed to herself".

Mary fell deeply in love with Fuseli: "From him Mary learnt much about the seamy side of life... Obviously there was a time when they were in love with one another, and playing with fire; the increase of Mary's love to the point where it became torture to her is hard to explain if it remained at all times entirely platonic." Mary wrote that she was enraptured by his genius, "the grandeur of his soul, that quickness of comprehension, and lovely sympathy". She proposed a platonic living arrangement with Fuseli and his wife, but Sophia rejected the idea and he broke off the relationship with Wollstonecraft.

In 1788 Joseph Johnson and Thomas Christie established the Analytical Review. The journal provided a forum for radical political and religious ideas and was often highly critical of the British government. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote articles for the journal. So also did the scientist, Joseph Priestley, the philosopher, Erasmus Darwin, the poet William Cowper, the moralist William Enfield, the physician John Aikin, the author Anna Laetitia Barbauld; the Unitarian minister William Turner; the literary critic James Currie; the artist Henry Fuseli; the writer Mary Hays and the theologian Joshua Toulmin.

Mary Wollstonecraft and her radical friends welcomed the French Revolution. In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. "I see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; a general amendment beginning in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priest giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience."

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. He also attacked political activists such as Major John Cartwright, John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Thomas Walker, who had formed the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation that promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform.

Burke attacked the dissenters who were wholly "unacquainted with the world in which they are so fond of meddling, and inexperienced in all its affairs, on which they pronounce with so much confidence". He warned reformers that they were in danger of being repressed if they continued to call for changes in the system: "We are resolved to keep an established church, an established monarchy, an established aristocracy, and an established democracy; each in the degree it exists, and in no greater."

Joseph Priestley was one of those attacked by Burke, pointed out: "If the principles that Mr Burke now advances (though it is by no means with perfect consistency) be admitted, mankind are always to be governed as they have been governed, without any inquiry into the nature, or origin, of their governments. The choice of the people is not to be considered, and though their happiness is awkwardly enough made by him the end of government; yet, having no choice, they are not to be the judges of what is for their good. On these principles, the church, or the state, once established, must for ever remain the same." Priestley went on to argue that these were the principles "of passive obedience and non-resistance peculiar to the Tories and the friends of arbitrary power."

Mary Wollstonecraft also felt that she had to respond to Burke's attack on her friends. Joseph Johnson agreed to publish the work and decided to have the sheets printed as she wrote. According to one source when "Mary had arrived at about the middle of her work, she was seized with a temporary fit of topor and indolence, and began to repent of her undertaking." However, after a meeting with Johnson "she immediately went home; and proceeded to the end of her work, with no other interruption but what were absolutely indispensable".

The pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man not only defended her friends but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society. This included the slave trade and way that the poor were treated. In one passage she wrote: "How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre."

The pamphlet was so popular that Johnson was able to bring out a second edition in January, 1791. Her work was compared to that of Tom Paine, the author of Common Sense. Johnson arranged for her to meet Paine and another radical writer, William Godwin. Henry Fuseli's friend, William Roscoe, visited her and he was so impressed by her that he commissioned a portrait of her by John Williamson. "She took the trouble to have her hair powdered and curled for the occasion - a most unrevolutionary gesture - but was not very pleased with the painter's work."

In 1791 Tom Paine published Rights of Man. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. "The whole system of representation is now, in this country, only a convenient handle for despotism, they need not complain, for they are as well represented as a numerous class of hard-working mechanics, who pay for the support of royalty when they can scarcely stop their children's mouths with bread."

The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. Paine also argued that a reformed Parliament would reduce the possibility of going to war. "Whatever is the cause of taxes to a Nation becomes also the means of revenue to a Government. Every war terminates with an addition of taxes, and consequently with an addition of revenue; and in any event of war, in the manner they are now commenced and concluded, the power and interest of Governments are increased. War, therefore, from its productiveness, as it easily furnishes the pretence of necessity for taxes and appointments to places and offices, becomes a principal part of the system of old Governments; and to establish any mode to abolish war, however advantageous it might be to Nations, would be to take from such Government the most lucrative of its branches. The frivolous matters upon which war is made show the disposition and avidity of Governments to uphold the system of war, and betray the motives upon which they act."

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy.

Mary Wollstonecraft's publisher, Joseph Johnson, suggested that she should write a book about the reasons why women should be represented in Parliament. It took her six weeks to write Vindication of the Rights of Women. She told her friend, William Roscoe: "I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject. Do not suspect me of false modesty. I mean to say, that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word."

In the book Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." She added: " I do not wish them (women) to have power over men; but over themselves".

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. Horace Walpole described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing.

Edmund Burke continued his attack on the radicals in Britain. He described the London Corresponding Society and the Unitarian Society as "loathsome insects that might, if they were allowed, grow into giant spiders as large as oxen". King George III issued a proclamation against seditious writings and meetings, threatening serious punishments for those who refused to accept his authority.

In November, 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft decided to move to Paris in an effort to get away from her unhappy love affair with Henry Fuseli: "I intend no longer to struggle with a rational desire, so have determined to set out for Paris in the course of a fortnight or three weeks." She joked that "I am still a spinster on the wing... At Paris I might take a husband for the time being, and get divorced when my truant heart longed again to nestle with old friends."

Mary arrived in Paris on 11th December at the start of the trial of King Louis XVI. She stayed in a small hotel and watched events from the window of her room: "Though my mind is calm, I cannot dismiss the lively images that have filled my imagination all the day... Once or twice, lifting my eyes from the paper, I have seen eyes glare through a glass-door opposite my chair, and bloody hands shook at me... I am going to bed - and, for the first time in my life, I cannot put out the candle."

Also in Paris at this time was Tom Paine, William Godwin, Joel Barlow, Thomas Christie, John Hurford Stone, James Watt and Thomas Cooper. She also met the poet, Helen Maria Williams. Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, that "Miss Williams has behaved very civilly to me, and I shall visit her frequently, because I rather like her, and I meet French company at her house. Her manners are affected, yet her simple goodness of her heart continually breaks through the varnish, so that one would be more inclined, at least I should, to love than admire her."

In March 1793 Mary met the writer, Gilbert Imlay, whose novel, The Emigrants, had just been published. The book appealed to Mary "because it advocated divorce and contained a portrait of a brutal and tyrannical husband". Mary was thirty-four and Imlay was five years older. "He was a handsome man, tall, thin and easy in his manner". Wollstonecraft was immediately attracted to him and described him as "a most natural, unaffected creature".

William Godwin, who witnessed the relationship while he was in Paris, claims that her personality changed during this period. "Her confidence was entire; her love was unbounded. Now, for the first time in her life, she gave a loose to all the sensibilities of her nature... Her whole character seemed to change with a change of fortune. Her sorrows, the depression of her spirits, were forgotten, and she assumed all the simplicity and the vivacity of a youthful mind... She was playful, full of confidence, kindness and sympathy. Her eyes assumed new lustre, and her cheeks new colour and smothness. Her voice became cheerful; her temper overflowing with universal kindness: and that smile of bewitching tenderness from day to day illuminated her countenance, which all who knew her will so well recollect."

Mary Wollstonecraft decided to live with Imlay. She wrote about those "sensations that are almost too sacred to be alluded to". The German revolutionary, George Forster in July 1793, met Mary soon after her relationship with Imlay began. "Imagine a five or eight and twenty year old brown-haired maiden, with the most candid face, and features which were once beautiful, and are still partly so, and a simple steadfast character full of spirit and enthusiasm; particularly something gentle in eye and mouth. Her whole being is wrapped up in her love of liberty. She talked much about the Revolution; her opinions were without exception strikingly accurate and to the point."

Mary gave birth to a girl on 14th May 1794. She named her Fanny after her first love, Fanny Blood. She wrote to a friend about how tenderly she and Gilbert loved the new child: "Nothing could be more natural or easy than my labour. My little girl begins to suck so manfully that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the Rights of Women."

In August 1794, Gilbert told Mary he had to go to London on business and he would make arrangements for her to join him in a few months. In reality he had deserted her. "When I first received your letter, putting off your return to an indefinite time, I felt so hurt that I know not what I wrote. I am now calmer, though it was not the kind of wound over which time has the quickest effect; on the contrary, the more I think, the sadder I grow... What sacrifices have you not made for a woman you did not respect! But I will not go over this ground. I want to tell you that I do not understand you."

Mary returned to England in April 1795 but Imlay was unwilling to live with her and keep up appearances like a conventional husband. Instead he moved in with an actress "exposing Mary to public humiliation and forcing her to acknowledge openly the failure of her brave social experiment... it is one thing to defy the opinion of the world when you are happy, another altogether to endure it when you are miserable." Mary found it especially humiliating that his "desire for her had lasted scarcely more than a few months".

One night in October 1795, she jumped off Putney Bridge into the Thames. By the time she had floated two hundred yards downstream she was seen by a couple of waterman who managed to pull her out of the river. She later wrote: "I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured."

Joseph Johnson managed to persuade her return to writing. In January 1796 he published a pamphlet entitled Letters Written During a Short Residence in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Mary was a good travel writer and provided some good portraits of the people she met in these countries. From a literary standpoint it was probably Wollstonecraft's best book. One critic commented that "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author this appears to me to be the book".

In March 1796, Mary wrote to Gilbert Imlay to tell them that she had finally accepted that their relationship was over: "I now solemnly assure you, that this is an eternal farewell... I part with you in peace". Mary was now open to starting another relationship. She was visited several times by the artist, John Opie, who had recently obtained a divorce from his wife. Robert Southey also showed interest and told a friend that she was the person he liked best in the literary world. He said her face was marred only by a slight look of superiority, and that "her eyes are light brown, and, though the lid of one of them is affected by a little paralysis, they are the most meaning I ever saw".

Her friend, Mary Hays, invited her to a small party where renewed her acquaintance with the philosopher, William Godwin. Although aged 40 he was still a bachelor and for most of his life he had shown little interest in women. He had recently published Enquiry into Political Justice and William Hazlitt had commented that Godwin "blazed as a sun in the firmament of reputation".

The couple enjoyed going to the theatre together and going to dinner with painters, writers and politicians, where they enjoyed discussing literary and political issues. Godwin later recalled: "The partiality we conceived for each other, was in that mode, which I have always regarded as the purest and most refined of love. It grew with equal advances in the mind of each. It would have been impossible for the most minute observer to have said who was before, and who was after... I am not conscious that either party can assume to have been the agent or the patient, the toil-spreader or the prey, in the affair... I found a wounded heart... and it was my ambition to heal it."

Mary Wollstonecraft married William Godwin in March, 1797 and soon afterwards, a second daughter, Mary, was born. The baby was healthy but the placenta was retained in the womb. The doctor's attempt to remove the placenta resulted in blood poisoning and Mary died on 10th September, 1797.

On this day in 1903 writer Cyril Connolly was born in Coventry, Warwickshire. Educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford he was a regular contributor to the New Statesman in the 1930s.

Connolly also co-edited Horizon (1939-41) with Stephen Spender and later was literary editor of the The Observer. Books by Connolly include the novel, The Rock Pool (1938), the autobiographical, Enemies of Promise (1938) and The Unquiet Grave (1944), a collection of aphorisms, reflections and essays.

After the Second World War Connolly was the principal book reviewer of the Sunday Times. He also published several other books including The Condemned Playground (1945), Previous Convictions (1964) and the Modern Movement (1965).

Cyril Connolly died ion 26th November 1974.

On this day in 1904 Max Shachtman was born in Warsaw, Poland. His family emigrated with his family to New York City when he was a small child.

Shackman was very interested in politics and as a teenager joined the Socialist Party of America. The right-wing leadership of the party opposed the Russian Revolution. However, those members who disagreed with this policy formed the Communist Propaganda League.

In February 1919, Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe, Louis Fraina, John Reed and Benjamin Gitlow created a left-wing faction that advocated the policies of the Bolsheviks in Russia. On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members who supported this faction. The process continued and by the beginning of July two-thirds of the party had been suspended or expelled.

In September 1919, Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Rose Pastor Stokes, Claude McKay, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the Communist Party of the United States. Within a few weeks it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

Initially, the American Communist Party was divided into two factions. One group that included Charles Ruthenberg, Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe and Benjamin Gitlow, favoured a strategy of class warfare. Another group, led by William Z. Foster, William Dunne and James Cannon, believed that their efforts should concentrate on building a radicalised American Federation of Labor. Shackman associated with the group led by Foster.

Shackman contributed to the party journal, The Young Worker. As the editor of The Labor Defender he joined with others such as William Z. Foster, Edna St Vincent Millay, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Floyd Dell in the campaign against the proposed execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

James Cannon, the first chairman of the American Communist Party, attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928. While in the Soviet Union he was given a document written by Leon Trotsky on the rule of Joseph Stalin. Convinced by what he read, when he returned to the United States he criticized the Soviet government. As a result of his actions, Cannon and his followers, including Shactman, were expelled from the party.

Shachtman, James Cannon and Martin Abern now joined with other Trotskyists to form the Communist League of America (CLA). The party also published the journal, The Militant. In July 1933, Shactman moved to France to live with Leon Trotsky and over the next few months worked as his secretary. In 1934 Shackman joined forces with Farrell Dobbs to publish The Organizer, a newspaper created to support the Minneapolis Teamster Strike.

In 1934 the party merged with the American Workers Party, to form the Workers Party of the United States, under the joint leadership of Abraham Muste and James Cannon. The party was dissolved in 1936 when it was decided that members should join the successful Socialist Party of America. During this period Shackman edited the New International, wrote a book on the Great Purge entitled, Behind the Moscow Trial (1936) and translated Leon Trotsky's The Stalin School of Falsification (1937).

Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, decided to expel the Trotskyists in 1937. Shachtman and James Cannon now decided to form the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). In March 1938, Shachtman and Cannon were part of a delegation sent to Mexico City to discuss the draft Transitional Program of the Fourth International with Leon Trotsky.

Shachtman became disillusioned with the Soviet Union when it signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact. These feelings were intensified when the Red Army invaded Poland (September, 1939) and Finland (November 1939). James Cannon continued to support the foreign policy of Joseph Stalin. Cannon, like Leon Trotsky, believed that the Soviet Union was "degenerated workers' state", whereas Shachtman argued that Stalin was developing an imperialist policy in Eastern Europe. Shachtman decided to leave the Socialist Workers Party and establish his own Workers Party. Other members included Martin Abern, C.L.R. James, Hal Draper, Joseph Carter, Julius Jacobson and Irving Howe.

Max Shachtman continued as editor of New International during the Second World War and in 1943 he predicted that the Red Army would impose Stalinism in Eastern Europe. In 1949 the Workers Party became the Independent Socialist League (ISL).

In 1962, Shachtman published The Bureaucratic Revolution: The Rise of the Stalinist States. In the book he argued that capitalism and Stalinism to be equal impediments to socialism. In 1958, the ISL dissolved so that its members could join the Socialist Party of America. Shachtman also believed that socialists should try to move the Democratic Party to the left from within. Shachtman also worked closely with Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement.

Shachtman's anti-communism moved him to the right and upset fellow members by refusing to condemn the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and his unwillingness to call for US armed forces to leave Vietnam. This alienated former supporters such as Walter Reuther and Michael Harrington. When George McGovern became the Democratic Party candidate in 1972 on an anti-war manifesto, Shachtman refused to endorse him.

Max Shachtman died on 4th November 1972.

On this day in 1908 Constance Lytton wrote to Adela Smith about the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU):

"I met some suffragettes down at the club in Littlehampton… They have come into personal first-hand contact with prison abuses. My hobby of prison reform has thereby taken on new vigour… I intend to interview the female inspector of Holloway prison, and will take part in the Suffragette breakfast with the next batch of released Suffrage prisoners on September 16. I had a long talk with Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. She mostly talked Woman Suffrage, about which, though I sympathize with the cause, she left me unconverted as to my criticisms of some of their methods."

On this day in 1909 Votes for Women reports on the attack by Vera Wentworth and Jessie Kenney on Herbert Asquith.

"It was decided to accost Asquith when he went to church on Sunday morning. "We then went up to the churchyard, whence we could command a good view of both of the Castle gates and the entrance of the church. We had not been there very long when we saw Mr Asquith making his way into church, so we waited until the service was over. As he was going from the church to the little door which led to the Castle we hastened up towards him, and he began to run. He was just slipping through the door when we caught him. He got wedged in the door, and a struggle ensued, in which his hat was knocked off. He tried to recover both his hat and his dignity, but looked extremely afraid. Mr Asquith, I think, quite understood the position as we had warned him at Clovelly that the women were not going to tolerate his attitude to them much longer. It was a real "Deeds not words" affair. Not a word was spoken on either side. Mr Asquith managed to squeeze through by the aid of someone who came to his help, and the door was shut."

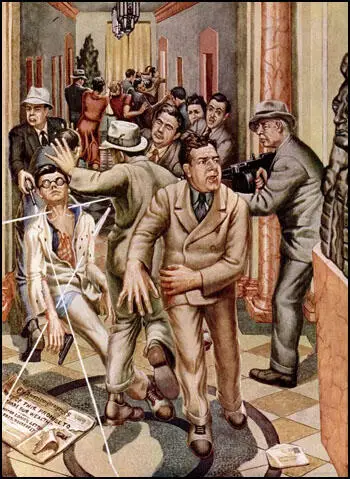

On this day in 1935 Huey Long is murdered. On 8th September, 1935, Pavy's son-in-law, Carl Weiss was told that rumours were circulating that his wife was the daughter of a black man. Weiss was furious when he heard the news and decided to pay Long a visit in the State Capitol Building. Long was in the governor's office, and so he waited by a marble pillar in the corridor. When Long left the office with John Fournet and six bodyguards, Weiss pulled out a .32 automatic and aimed it at Long. Weiss fired and hit Long in the abdomen. The bodyguards opened fire and Weiss died on the spot. A bullets fired by one of the bodyguards ricocheted off the pillar and hit Long in the lower spine.

At first it was thought that Long was not seriously wounded and an operation was carried out to repair his wounds. However, the surgeons had failed to detect that one of the bullets had hit Long's kidney. By the time this was discovered, Long was to weak to endure another operation and died on 10th September, 1935. According to his sister, Lucille Long, his last words were: "Don't let me die, I have got so much to do." His book, My First Days in the White House, was published posthumously.

On this day in 1976 Dalton Trumbo died of a heart attack in Los Angeles, California.

James Dalton Trumbo was born in Montrose, Colorado on 5th December, 1905. Educated at the University of Colorado. Trumbo wanted to be a writer and by the early 1930s his articles and stories appeared in Saturday Evening Post, McCall's Magazine, Vanity Fair and the film magazine, the Hollywood Spectator .

In 1935 Trumbo published his first novel, Eclipse, a satire about a self-made businessman. Trumbo's most popular novel, Johnny Got His Gun, about a disfigured British officer in the First World War, won a National Book Award in 1939.

In the 1930s Trumbo worked on several movies including Love Begins at Twenty (1936), Road Gang (1936), Tugboat Princess (1936), That Man's Here Again (1937), Devil's Playground (1937), Fugitives For a Night (1938), A Man to Remember (1938) and Career (1939). Trumbo, who joined the Communist Party in 1943, was also active in the Screen Writers Guild.

Other films written by Trumbo included Five Came Back (1939), Curtain Call (1940) and Kitty Foyle (1940), a film for which he was nominated for an Academy Award Oscar, A Guy Named Joe (1943), Tender Comrade (1943) and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944).

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

In 1947 nineteen members of the film industry who were suspected of being communists were called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. This included Trumbo, Ring Lardner Jr, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Edward Dmytryk, Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Larry Parks, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

Trumbo appeared before the HUAC on 28th October, 1947. He was denied the right to make an opening statement. In it he wanted to make the point that the HUAC was having a damaging impact on world opinion: "As indicated by news dispatches from foreign countries during the past week, the eyes of the world are focused today upon the House Committee on Un-American Activities. In every capital city these hearings will be reported. From what happens during the proceedings, the peoples of the earth will learn by precept and example precisely what America means when her strong voice calls out to the community of nations for freedom of the press, freedom of expression, freedom of conscience, the civil rights of men standing accused before government agencies, the vitality and strength of private enterprise, the inviolable right of every American to think as he wishes, to organize and assemble as he pleases, to vote in secret as he chooses."

Trumbo was asked by Robert E. Stripling if he was a member of the Screen Writers Guild. He refused to answer the question: "Mr. Stripling, the rights of American labor to inviolably secret membership have been won in this country by a great cost of blood and a great cost in terms of hunger. These rights have become an American tradition. Over the Voice of America we have broadcast to the entire world the freedom of our labor... You asked me a question which would permit you to haul every union member in the United States up here to identify himself as a union member, to subject him to future intimidation and coercion. This, I believe is an unconstitutional question."

Dalton Trumbo also refused to admit he was a member of the American Communist Party. Trumbo was removed from the room and HUAC investigator, Louis Russell, now read out a nine page report on his Communist Party affiliations. John Parnell Thomas now stated: "The evidence presented before this Committee concerning Dalton Trumbo clearly indicates that he is an active Communist Party member. Also the fact that he followed the usual Communist line of not responding to questions of the Committee is definite proof that he is a member of the Communist Party. Therefore, by unanimous vote of the members present, the subcommittee recommends to the full committee that Dalton Trumbo be cited for contempt of Congress." Trumbo was found guilty of contempt of Congress and was sentenced to ten months in prison.

Blacklisted by the Hollywood studios, Trumbo and his wife decided to go and live in Mexico City. They were joined by their friends, Ring Lardner Jr, Ian McLellan Hunter, Hugo Butler, John Bright, Jean Rouverol and Albert Maltz. On Saturday mornings this group and their children used to have picnic lunches and play baseball together. The FBI were spying on them in Mexico and according to declassified reports, the agents believed that these picnics were cover for "Communist meetings." They were later joined by Martha Dodd and Frederick Vanderbilt Field.

Trumbo asked Hunter, who had not yet been blacklisted, to approach William Wyler with an idea for a film. Ring Lardner Jr. explained in his autobiography, I'd Hate Myself in the Morning (2000): "Ian got involved only by agreeing to front for the already-blacklisted Trumbo. It was he who had come up with the idea of a movie about a reporter and a princess on the loose in Rome. Paramount paid $50,000 for what it assumed to be Ian's (but was really Trumbo's) first draft, and hired him to do a rewrite... The result, much to Ian's (and Trumbo's) surprise, was a wonderful movie, starring Gregory Peck and the unknown Audrey Hepburn." In 1953 Roman Holiday won the Academy Award for the best screenplay (Trumbo did not get credit for this work until after the blacklist was lifted).

Trumbo carried on writing screenplays by using pseudonyms such as Ben Parry, Robert Rich and Sally Stubblefield. This included Roman Holiday (1953), which won the Academy Award for best screenplay, Carnival Story (1954), One Man Mutiny (1955), The Boss (1956), The Brave One (1956), another Academy Award winner, The Brothers Rico (1957), The Deerslayer (1957), The Green-Eyed Blonde (1957), The Cowboy (1958) and Terror in a Texas Town (1958).

In 1959 Frank Sinatra announced that he proposed to break the blacklist by employing Albert Maltz as the screenwriter of his proposed film, The Execution of Private Slovik, based on the book by William Bradford Huie. Sinatra soon came under attack for his decision. He nearly came to blows with John Wayne, who called him a "Commie" when they met in the street. However, what really hurt Sinatra was the criticism he received in the press. This included claims that his friend, John F. Kennedy, also wanted an end to the blacklist. Sinatra issued a statement to the press: "I would like to comment on the attacks from certain quarters on Senator John Kennedy by connecting him with my decision on employing a screenwriter. This type of partisan politics is hitting below the belt... I make movies. I do not ask the advice of Senator Kennedy on whom I should hire. Senator Kennedy does not ask me how he should vote in the Senate."

Michael Freedland, the author of Witch-Hunt in Hollywood (2009) argues that "Kennedy didn't like the association with the name of one of the Hollywood Ten. He would soon run from President and he was worried that he could harm him." A few days later Sinatra took out another paid-for advertisement in the newspapers: "In view of the reaction of my family, friends and the American public I've instructed my lawyers to make a settlement with Albert Maltz. My conversations with Maltz indicate that he has an affirmative, pro-American approach to the story, but the American public has indicated it feels that the morality of hiring Maltz is the most crucial matter and I will accept this majority opinion."

In 1960 Trumbo became the first blacklisted writer to use his own name when he wrote the screenplay for the film Spartacus. Based on the novel by another left-wing blacklisted writer, Howard Fast, is a film that examines the spirit of revolt. Trumbo refers back to his experiences of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. At the end, when the Romans finally defeat the rebellion, the captured slaves refuse to identify Spartacus. As a result, all are crucified. Ironically, much of Spartacus was filmed on land owned by William Randolph Hearst. It was Hearst's newspapers that played such an important role in making McCarthyism possible.

As Ring Lardner Jr., another member of the Hollywood Ten, pointed out in his autobiography, I'd Hate Myself in the Morning (2000): “Sinatra caved in, paying off Maltz in cash and eventually scrubbing the project, perhaps partly out of fear of harming his friend John F. Kennedy, a candidate for President at the time. (Following the election that fall, however, the President-elect and his brother, Attorney-General-to-be Robert Kennedy, crossed a picket line to see Spartacus at a theater in Washington D.C., and pronounced it good.)”

After the blacklist was lifted, Trumbo wrote the screenplay for Lonely Are the Brave (1962), The Sandpiper (1965) and The Fixer (1968). In 1970 Trumbo's anti-war novel, Johnny Got His Gun, was republished. The book had been withdrawn during the Second World War, had a tremendous impact on the generation being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War.

In 1970 Trumbo argued that all screenwriters were victims during McCarthyism. "Some suffered less than others, some grew and some diminished, but in the final tally we were all victims because almost without exception each of us felt compelled to say things he did not want to say, to do things that he did not want to do, to deliver and receive wounds he truly did not want to exchange. That is why none of us - right, left, or centre - emerged from that long nightmare without sin."

Albert Maltz diagreed with this view of the situation. In an interview he gave to the New York Times in 1972 he compared the experiences of Adrian Scott and Edward Dmytryk: "There is currently in vogue a thesis pronounced by Dalton Trumbo which declares that everyone during the years of blacklist was equally a victim. This is factual nonsense and represents a bewildering moral position.... Adrian Scott was the producer of the notable film Crossfire in 1947 and Edward Dmytryk was its director. Crossfire won wide critical acclaim, many awards and commercial success. Both of these men refused to co-operate with the HCUA. Both were held in contempt of the HCUA and went to jail. When Dmytryk emerged from his prison term he did so with a new set of principles. He suddenly saw the heavenly light, testified as a friend of the HCUA, praised its purposes and practices and denounced all who opposed it. Dmytryk immediately found work as a director, and has worked all down the years since. Adrian Scott, who came out of prison with his principles intact, could not produce a film for a studio again until 1970. He was blacklisted for 21 years. To assert that he and Dmytryk were equally victims is beyond my comprehension."

In 1973 Dalton Trumbo joined forces with Donald Freed and Mark Lane to write the political thriller, Executive Action, which dealt with an alleged conspiracy to murder John F. Kennedy. The film opened to a storm of controversy with the suggestion that Kennedy had been a victim of the Military-Industrial Complex and was removed totally from the movie theaters by early December 1973.