Jean Rouverol

Jean Rouverol, the daughter of playwright Aurania Rouverol (1886–1955), was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on 8th July, 1916. She later recalled: "I'd been brought up in a good Republican (albeit feminist) household, safely middle-class."

Rouverol had a strong desire to become an actress and at the age of sixteen her mother wrote a play for her that opened in November 1933. However, it only ran for three weeks. It was while acting in New York City that she first became interested in politics.

Rouverol later wrote: "Walking from the subway en route to the theater and back on those chilly November nights, I'd been astonished to see gaunt men in threadbare coats, sheltering in doorways against the weather. The newspapers had been carrying stories about soup kitchens and unemployment marchers, of course, but it was another matter altogether to see with one's own eyes homeless human beings huddled in doorways."

Rouverol now moved to Hollywood and at the age of seventeen she obtained her first part as the daughter of W. C. Fields in the comedy, It's a Gift (1934). This was followed by appearances in Bar 20 Rides Again (1935), Mississippi (1935), Private Worlds (1935) and Fatal Lady (1936). She also starred with Norman Forster and Donald Cook in The Leavenworth Case (1936).

Rouverol met Hugo Butler in 1937. In her autobiography Refugees from Hollywood (2000) she recalled: "I was quite dazzled by Hugo Butler. He was twenty-two (to my twenty), and he had, I thought, a lovely wit. He also had brown eves that missed nothing; a light sprinkle of freckles; a fresh, almost English complexion and pleasant, even features; reddish brown hair and a sturdy body (well, maybe the tiniest bit overweight), which seemed to me to house delightful high school boy who was still growing up. In a tweed sports jacket, argyle socks, and square-toed brogues and with a faint scent of aftershave, he even dressed enchantingly, I thought And when he phoned me later, offering to drive rue to a party we'd all been invited to, in order to obviate my having to find my own way there, I was convinced. Any young man who used the word obviate in casual conversation was the man for me."

Rouverol continued to work in Hollywood and films she appeared in included Stage Door (1937), The Road Back (1937), Western Jamboree (1938), The Law West of Tombstone (1938), Annabel Takes a Tour (1938) and Jack Pot (1940). In 1940 she married Hugo Butler and during the next few years she gave birth to four children. During this period she performed on radio as Betty Carter on One Man's Family. "For a dozen years or so I'd had a part on a long-running radio serial called One Man's Family - a rambling, lovable piece of Americana that whole families, all over the United States, had grown up listening to."

A poll conducted by Fortune Magazine in 1942 found that only 40 percent of the American public opposed socialism, and well over 25 percent supported it, while 35 percent said they had an open mind. According to Lary May, the author of The Big Tomorrow: Hollywood and the Politics of the American Way (2000): "In other words, over 60 percent of the population saw the possibility of socialism as the American Way. Other pollsters showed that majorities also supported the insurgent labor union movement." Rouverol and Hugo Butler shared this new radicalism and joined the American Communist Party in 1943. They were recruited by their friend, Waldo Salt. According to her account in her autobiography, Refugees from Hollywood (2000): "And that's how we joined. It wasn't a difficult decision. The political climate encouraged it; the Russians were our gallant allies, suffering terrible casualties but stopping the Germans at Stalingrad. Here at home, the Communist Party was legal; its candidates were on the ballot, and its primary spokesperson was Earl Browder, a gradualist who was saving that perhaps revolution was not inevitable after all, that a peaceful transition to socialism might be possible. But perhaps the most telling reason was that most of our friends were already members."

Rouverol was keen to become a writer and her first screenplay So Young So Bad, about a girl's reform school, eventually got accepted in 1950. It was directed by Bernard Vorhaus and the cast included Paul Henreid, Catherine McLeod, Anne Francis, Anne Jackson, Rita Moreno and Grace Coppin. This was followed by a couple of episodes of the television series, Search for Tomorrow.

Rouverol and Hugo Butler were no longer a member of the American Communist Party but they were worried about the political climate in the United States. In 1947 nineteen members of the film industry who were suspected of being communists were called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. This included Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Larry Parks, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

The first ten witnesses called to appear before the HUAAC, Biberman, Bessie, Cole, Maltz, Scott, Trumbo, Dmytryk, Lardner, Ornitz and Lawson, refused to cooperate at the September hearings and were charged with "contempt of Congress". They were all found guilty and given the maximum sentence of a year in prison. The case went before the Supreme Court in April 1950, but with only Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas dissenting, the sentence was confirmed.

Expected to be called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee Rouverol and Butler decided to flee to Mexico City where they were joined by their friends, Ring Lardner Jr., Dalton Trumbo, Albert Maltz, Ian McLellan Hunter and their partners. On Saturday mornings this group and their children used to have picnic lunches and play baseball together. The FBI were spying on them in Mexico and according to declassified reports, the agents believed that these picnics were cover for "Communist meetings." They were later joined by Martha Dodd and Frederick Vanderbilt Field.

While in Mexico Hugo Butler worked with another refugee from fascism, the Spanish director, Luis Buñuel, on his film The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1954). Rouverol later wrote: "Buñuel was a fascinating figure. A not very tall man with simian arms and shoulders, balding head, and exophthalmic eyes, he was married to a tall, blond, handsome Frenchwoman he'd met during his early filmmaking days in Paris, and as he and Hugo became more immersed in preparations for Crusoe, we went often to Sunday afternoon comidas in their backyard, where Jeanne Buñuel cooked paella over an outdoor stove."

The only person who would give them work as writers was the young film director, Robert Aldrich. This included the writing of Autumn Leaves (1956). According to the authors of Blacklisted: The Film Lover's Guide to the Hollywood Blacklist (2003): "The tale of an aging, unmarried woman (Joan Crawford) who falls in love with a young man (Cliff Robertson) but whose good sense is overcome by his ardor. Beautifully cinematic scenes later become stock film sexuality, including Crawford first afraid to show herself in a bathing suit at the beach, then being pulled joyfully into the waves by Robertson, both surrounded by symbolic explosions of surf."

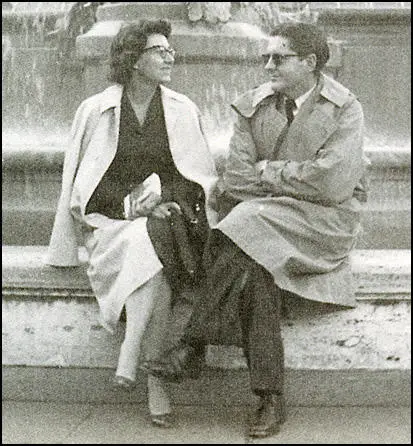

In 1960 Rouverol and Hugo Butler moved to Rome where he was working on a script for the director, Robert Aldrich, that was eventually filmed as Sodom and Gommah! (1962). Soon afterwards Butler was diagnosed as suffering from arteriosclerotic brain disease. As Rouverol pointed out: "His dementia, finally diagnosed (wrongly) as Alzheimer's disease, became painfully apparent not long after we moved back to the States in late 1964. A bit more than three years later, at age fifty, he died of a massive heart attack."

In the 1970s, Rouverol began writing scripts for television. This included Little House on the Prairie, Guiding Light, Search for Tomorrow and As the World Turns. Books by Rouverol include Pancho Villa (1972), Juarez, A Son of the People (1973), Storm Wind Rising (1974), Writing for Daytime Drama (1992) and Refugees from Hollywood: A Journal of the Blacklist Years (2000).

Primary Sources

(1) Jean Rouverol, Refugees from Hollywood (2000)

I'd been brought up in a good Republican (albeit feminist) household, safely middle-class; my first real glimpse of poverty had been during the truncated run of a play my mother had written for me, which had opened on Broadway in November 1933 (and closed, alas, three weeks later). Walking from the subway en route to the theater and back on those chilly November nights, I'd been astonished to see gaunt men in threadbare coats, sheltering in doorways against the weather. The newspapers had been carrying stories about soup kitchens and unemployment marchers, of course, but it was another matter altogether to see with one's own eyes homeless human beings huddled in doorways.

(2) Jean Rouverol, Refugees from Hollywood (2000)

With our ever-present need for survival money in mind, Hugo had arranged to start work immediately on a screenplay, The Big Night, with his director friend Joseph Losey, who had his own reasons for wanting to avoid Los Angeles. As a student, Joe had gone to the Soviet Union to study Russian theater-innocent enough when one's in college, but from a Cold War perspective, something that might look very suspicious indeed. So now, packing a portable typewriter, piles of yellow pads, and a minimum of baggage, the two men set out to move from one obscure motel to another through central and northern California, planning their script on the run and staying well out of the way of U.S. marshals.

As for me: I had no writing job now, but I did have a little radio job, the only relic of my acting days. For a dozen years or so I'd had a part on a long-running radio serial called One Man's Family - a rambling, lovable piece of Americana that whole families, all over the United States, had grown up listening to. I had developed a strong feeling of fellowship with the other cast members, but they knew little of my political life and nothing whatever of our current troubles. Now, turning up once or twice a week for taping sessions at the broadcasting station and confiding nothing to these nice people made me feel as though I were in disguise.

(3) Jean Rouverol, Refugees from Hollywood (2000)

I was quite dazzled by Hugo Butler. He was twenty-two (to my twenty), and he had, I thought, a lovely wit. He also had brown eves that missed nothing; a light sprinkle of freckles; a fresh, almost English complexion and pleasant, even features; reddish brown hair and a sturdy body (well, maybe the tiniest bit overweight), which seemed to me to house delightful high school boy who was still growing up. In a tweed sports jacket, argyle socks, and square-toed brogues and with a faint scent of aftershave, he even dressed enchantingly, I thought And when he phoned me later, offering to drive rue to a party we'd all been invited to, in order to "obviate" my having to find my own way there, I was convinced. Any young man who used the word obviate in casual conversation was the man for me.

In any event, as I spoke of mv brief fling with the Left at the table that day in the busy commissary, it was regarded by all of us as an amusing vagary, merely a distraction from the more serious business of getting on with our lives.

Not for long, though.

By the time we had courted, married, and were living in our own tiny Hollywood apartment - and oh, how wonderful it was to be grown-up, working, free of one's mother, and utterly, wildly in love with one's husband! - the post-Depression years and the rise of Fascism in Europe had the film industry in a ferment. Stirred by Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath, we had become interested in the plight of California's migrant workers, which local left-wingers (among others) were trying to alleviate.

(4) Jean Rouverol, Refugees from Hollywood (2000)

We were both living as normal a life as people can in wartime, working, watching our children become delightful, idiosyncratic human beings when Waldo Salt dropped by one afternoon with his invitation to join the party. And before the next day was out, bingo had said to me, almost casually, "Honey I thought I'd give Waldo the nod. Okay".

And that's how we joined. It wasn't a difficult decision. The political climate encouraged it; the Russians were our gallant allies, suffering terrible casualties but stopping the Germans at Stalingrad. Here at home, the Communist Party was legal; its candidates were on the ballot, and its primary spokesperson was Earl Browder, a gradualist who was saving that perhaps revolution was not inevitable after all, that a peaceful transition to socialism might be possible. But perhaps the most telling reason was that most of our friends were already members.

For me, a joiner by nature, those once-or twice-a-month meetings at someone's house, with eight or ten friends sitting about a living room, fueled by coffee and Danish and discussing dialectical materialism, were an intriguing experience. It wasn't just a political commitment we'd made, I found; we had also committed ourselves to a fellowship, to a group of people we loved and respected. (I remember an old-time member, an aging character actress, telling me: "You always love your first group.")

In spite of my deep affection for my "group," however - a motley assortment of publicists, screen-story analysts, character actors, a teacher or two, a sprinkling of not terribly prosperous doctors and dentists, and an assortment of left-wing wives either with or without careers of their own -I was sharply aware that the group lingo had been assigned to, almost entirely male and made up of fairly prominent screenwriters, With a sprinkling of producers and a couple of directors, which met in Beverly Hills, was in career terms a far more prestigious one. I wondered who made these assignments and on what basis.

(5) Jean Rouverol, Refugees from Hollywood (2000)

For whatever reason, we had never struck up a real friendship with thc Maltzes, though of course we had infinite respect for Albert's achievements as a playwright with New York's Group Theater and as a writer of short stories and screenplays. Like Trumbo and Ring, Albert was one of the Hollywood Ten who'd received a full one-year sentence, but unlike them, he had found no way to adapt to prison life. He had come down with infectious hepatitis early in his stay, prison food made him even sicker than he already was, and he had faced the last months of his sentence in real fear of re-arrest and another jailing - which, he was convinced, would kill him.

So, according to his wife Margaret's telling of it, when he was due for release, he had arranged for her to meet him with the family car loaded for immediate emigration; she'd met him at the prison gates, and they had driven all night, not stopping till they were across the border. Unlike most of the blacklistees, however, he had no need to live close to the local film industry, because, I gathered, he had an independent income and could afford to write what he pleased. So he, Margaret, and their two adopted children were able to settle here, in a residential suburb of Mexico's lotus land, in a pleasant house with a pool...

Having the Maltzes as neighbours, however, raised a few small private problems for Hugo and me. For while we were fond of Margaret, our feelings about Albert were still decidedly conflicted... In short, the Maltzes could in no way replace the Hunters or the Lardners, whose return to the States had left a huge hole in our lives - a feeling that became acute late in 1953 when the Trumbos announced their decision to go back too.

(6) Jean Rouverol, Refugees from Hollywood (2000)

Earl in the 1990s, public attitudes about the blacklist began to change. Under relentless pressure from Paul Jarrico, the Motion Picture Academy took steps to restore the (till then) pseudonymous writing credits of some of their award-winning films, and in 1992 the Writers Guild of America, announced that at their annual awards event that year, they would restore Albert Maltz's screenplay credit on Broken Arrow and Trumbo's story credit on Roman Holiday... The widows of both Maltz and Trumbo, the guild announced, would be present to receive the awards...

Warren Beatty, fresh from playing radical John Reed in Reds, took the micro-phone and, for the benefit of those in the audience too young to have lived through it all, gave a brief history of the blacklist and Trumbo's part in it. Then he introduced Cleo Trumbo. And as she - shy as always - came onstage, the whole audience got to its feet and gave her a standing ovation. It went on for ten minutes... When the tumult finally died down, and Cleo was given the Oscar and it was time for thanks on Trumbo's behalf, she was so close to tears, she could hardly form the words.