On this day on 10th March

On this day in 1629 King Charles I dissolves Parliament and governed alone for the next eleven years. Barry Coward, the author of The Stuart Age: England 1603-1714 (1980) has argued that his problems with Parliament was partly caused by his poor communication skills: "Charles was a shy man of few words, possibly as a result of a speech defect... Consequently, his contemporaries found that he was unapproachable and, what was worst, uncommunicative, especially in parliament, where his intentions and his actions often went unexplained, leaving others free to interpret them to his disadvantage. Charles also showed that he possessed none of his father's political shrewdness or flexibility."

Charles now had a problem. He was very short of money, but under the terms of the Magna Carta taxes could not be imposed without the agreement of Parliament. Charles now began raising money by exacting forced loans from his wealthier subjects. He also attempted to make money from selling knighthoods. In the 16th century, all men with land worth £40 a year were required to pay for a knighthood. However, rapid inflation pushed many into this category "who were below the social level of knights and had no relish for an honour which might well oblige them to perform functions in the local communities for which they had neither the leisure, the qualifications, nor the necessary status."

Oliver Cromwell and other Puritans refused to buy what had once been an honour. Charles reacted to this by fining those who were unwilling to pay this money. In April 1631 Cromwell and six others from his neighbourhood appeared before the royal commissioners for repeatedly refusing to buy a knighthood. He was found guilty and fined £10. It was reported that Cromwell was so unhappy about this that he considered the idea of going to live in North America.

Charles found other ways of raising money. Another scheme involved selling monopoly rights to businessmen. This meant that only one person had the right to distribute certain goods such as bricks, salt and soap. This policy was unpopular as it tended to increase the price of these goods.

In 1633 Charles appointed William Laud, as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud argued that the king ruled by Divine Right. He claimed that the king had been appointed by God and people who disagreed with him were bad Christians. Laud believed that Church reforms had gone too far. Anglicans tended to support the policies of Laud but the Puritans strongly disagreed with him. When Laud gave instructions that the wooden communion tables in churches should be replaced by stone altars. Puritans accused Laud of trying to reintroduce Catholicism.

In 1635 King Charles I faced a financial crisis. Unwilling to summon another Parliament, he had to find other ways of raising money. He decided to resort to the ancient custom of demanding Ship Money. In the past, whenever there were fears of a foreign invasion, kings were able to order coastal towns to provide ships or the money to build ships. This time he extended the levy to inland counties as well, on the grounds that "the charge of defence which concerneth all men ought to be supported by all."

Charles sent out letters to sheriffs reminding them about the possibility of an invasion and instructing them to collect Ship Money. Encouraged by the large contributions he received, Charles demanded more the following year. Whereas in the past Ship Money had been raised only when the kingdom had been threatened by war, it now became clear that Charles intended to ask for it every year. Several sheriffs wrote to the king complaining that their counties were being asked to pay too much. Their appeals were rejected and the sheriff's now faced the difficult task of collecting money from a population overburdened by taxation.

Gerald E. Aylmer has argued that ship money was in fact a more reasonable tax than the traditional forms of collecting money from the population. Most king's had relied on taxes on movable property (a subsidy). "Ship money had in fact been a more equitable as well as a more efficient tax than the subsidy because it was based on a far more accurate assessment of people's wealth and property holdings."

John Hampden was a strong critic of the king and in the House of Commons he had said that his actions was undermining the Protestant religion. "The alteration of government... goes no less than the subversion of the whole state? Hemmed in with enemies; it is now a time to be silent, and not to show his Majesty that a man that has so much power uses none of it to help us? If he be no papist, papists are friends and kindred to him."

On this day in 1779, Frances (Fanny) Milton, the middle child of William Milton (1743–1824), and his first wife, Mary Gresley Milton, was born in Bristol.. Her father was the vicar of Heckfield, Hampshire. According to Pamela Neville-Sington the author of Frances Trollope (1998): "William Milton... preferred inventing gadgets to saving souls, and his most important idea was the creation of a tidal bypass to control the water levels of the Avon, allowing ships to sail in and out of Bristol more freely. Of his three children, Frances - or Fanny as she was known to her friends and family - resembled her father most. Like him, she was incapable of sitting still and doing nothing if there was a problem to be solved or a situation to be improved. Without the guidance of her mother, who died when Fanny was only five or six years old, she also learned to be self-reliant. Together these traits - initiative, tenacity, and independence of mind - were to give her the courage, strength, and ability to overcome the many crises which she would have to face in her lifetime; but they also made her sometimes act rashly, without thinking, and thus court disaster."

In 1800 her father married Sarah Partington. Fanny did not like her stepmother and along with her sister, Mary, decided to live with her brother Henry in London. When she was twenty-nine she met the barrister, Thomas Trollope. He considered her to have a petite figure, a pleasant face, and "the neatest foot and ankle" on the dance floor. After a year's courtship, they married on 23rd May 1809. Her first child died soon after being born. Over the next nine years Fanny gave birth to six more children: Thomas, Henry, Arthur, Anthony, Cecilia, and Emily.

Thomas later recalled: "My mother's disposition… was of the most genial, cheerful, happy, enjoué nature imaginable… and to any one of us a tête-à-tête with her was preferable to any other disposal of a holiday hour". By contrast, Thomas Anthony, was a harsh father and used to punish the children for small misdemours by pulling their hair. It has been speculated that his agrressive behaviour was caused by the effects of calomel, a mercury-based drug which he took for chronic migraine.

Thomas Trollope eventually took over a 160 acre farm. He had no experience in farming and he was soon heavily in debt. Thomas Trollope's son, Anthony Trollope, said that everything his father touched ended in failure: "But the worse curse to him of all was a temper so irritable that even those he loved the best could not endure it. We were all estranged from him, and yet I believed he would have given his heart's blood for any of us. His life as I knew it was one long tragedy."

In 1827 Frances Trollope and her two daughters spent time visiting Frances Wright at Nashoba, a community in the backwoods of Tennessee dedicated to the education and emancipation of slaves. According to her biographer, Pamela Neville-Sington: "Fanny thought it Henry's best chance to find a good prospect in life; she also hoped to ease the family's financial burdens back home while escaping her husband's dreadful temper. She left her two remaining sons, Tom and Anthony, at home to continue their education. When her friend's utopian dream turned out to be a malaria-ridden swamp, Fanny decamped and headed up the Mississippi to Cincinnati, Ohio."

While living in Cincinnati, Frances Trollope opened up what has been called "America's first shopping mall", the Cincinnati Bazaar. The venture was a disaster and see ended up bankrupt and ill with malaria. She began spending a great deal of time with a young French artist, Auguste Hervieu, who, despite the gossip, was in fact nothing more than a devoted friend. In August 1831 she returned to England.

The following year she published Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832). The book was an attack of what she believed was the hypocrisy of the Americans. "With one hand hoisting the cap of liberty, and with the other flogging their slaves. You will see them one hour lecturing their mob on the indefeasible rights of man, and the next driving from their homes the children of the soil, whom they have bound themselves to protect by the most solemn treaties."

Thomas Trollope, still heavily in debt, died in 1835. Frances Trollope decided to become a novelist. Her novels were very popular and it was not long before she was able to pay off her husband's debts. Trollope believed that novels should deal with important social issues. Her novel, Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw, was about the evils of slavery, and The Vicar of Wrexhill tackled the subject of church corruption.

In 1839 Frances Trollope decided to write a novel on young factory workers. She had become interested in the subject after reading a copy of the book on the life of Robert Blincoe in 1832. Before writing the novel she carried out a fact-finding mission to Manchester. Frances Trollope was accompanied by the French artist, Auguste Hervieu, who had been commissioned to produce illustrations for the book. Trollope and Hervieu spent several weeks visiting factories and having meeting with people involved in the campaign for factory reform. This included Richard Oastler, Joseph Raynor Stephens and John Doherty, the editor of The Poor Man's Advocate .

The first part of Michael Armstrong: Factory Boy, was published in 1840. Frances Trollope was the first woman to issue her novels in monthly parts. Costing one shilling a month, it was also the first industrial novel to be published in Britain. The conservative The Athenaeum, gave it a hostile reception and compared Trollope to James Rayner Stephens: "The most probable immediate effect of her pennings and her pencillings will be the burning of factories and the plunder of property of all kinds. The Rev. James Rayner Stephens has recently been sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment for using seditious and inflammatory language. The author of Michael Armstrong deserves as richly to have eighteen months in Chester Gaol. But if the text be bad, still worse are the plates that illustrate it. What, for instance, must be the effect of the first picture in No. V1 (mill children competing with pigs for food), on the heated imaginations of our great manufacturing towns, figuring as they do in every book-seller's window."

Richard Henry Horne, the author of A New Spirit of the Age (1844) also disliked her novels: "Mrs Trollope takes a strange delight in the hideous and revolting. Nothing can exceed the vulgarity of Mrs Trollope's mob of characters. We have heard it urged on behalf of Mrs. Trollope that her novels are, at all events, drawn from life. So are sign paintings."

Of her novels, The Widow Barnaby and The Widow Married were the most successful. Pamela Neville-Sington has argued: "In her later novels, whether set in a cathedral town, a country estate, or London's West End, Fanny combined witty social commentary with strong and often melodramatic plots. At its best, Fanny's writing is subtle and well observed and, even in the most far-fetched romance, she is able to convey with great skill the foibles and follies of human nature - and of English manners in particular. She astutely aimed to hit the somewhat lowbrow taste of the circulating library."

By the time Frances Trollope died in Florence on 6th October 1863, aged eighty-four, she had written forty books. Her sons, Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) and Thomas Adolphus Trollope (1810-1892), were both successful writers.

On this day in 1817 about 10,000 people attended meeting on parliamentary reform in Manchester. Earlier that year three working-class Radicals in Manchester, John Johnson, John Bagguley and Samuel Drummond decided to organise a protest march as a method of drawing attention to the problems of unemployed spinners and weavers in Lancashire. William Benbow, a Nonconformist preacher, became involved in organising the march.

The plan was for the men to take a petition to the Prince Regent. On the way to London the men hoped to hold meetings and to gain the support of other textile workers. It was believed that by the time they reached London there would be over 100,000 marchers willing to tell the royal family about the distress being caused by the growth of the factory system.

The leaders of the moderate reformers in Manchester, Archibald Prentice, John Shuttleworth and John Edward Taylor, were opposed to the proposed march. John Knight, Joseph Johnson, John Saxton and other Radical leaders in Manchester had doubts about the wisdom of this planned demonstration and decided not to encourage their supporters to take part in the march.

On the long march to London the organisers decided that each man should carry a blanket. As well as keeping them warm at night, the blanket would indicate to the people who saw them on the march that they were weavers. As a result of the men carrying these blankets the demonstration became known as the March of the Blanketeers. Spies employed by the Manchester Magistrates sent in reports suggesting that the blanketeers might resort to violence on the march. The Magistrates therefore decided to make sure that the march to London did not take place.

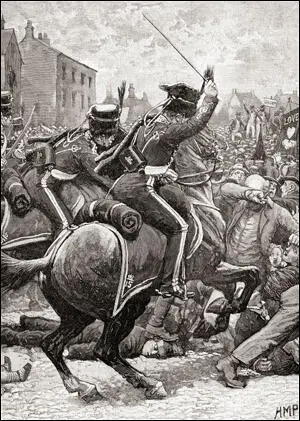

Johnson, Bagguley and Drummond planned to start the march off with a large meeting at St. Peter's Field in Manchester on 10th March, 1817. It is estimated that about 10,000 people attended, making it the largest meeting ever organised in Manchester. While the leaders of the meeting were speaking to the crowd, the King's Dragoon Guards were sent in by the Magistrates to arrest the leaders and to disperse the meeting. Twenty-nine men, including John Bagguley and Samuel Drummond, were taken into custody.

A large number of the men were determined to march to London. The blanketeers were followed by the cavalry. One group was attacked a mile from the city centre. Others were apprehended at Macclesfield and Ashbourne. The worst violence took place at Stockport where several received sabre wounds and one man was shot dead. After the events of 10th March, 1817, the Magistrates decided that they needed their own military force that they could use during social unrest. The Magistrates therefore decided to form the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry.

On this day in 1867 Lillian Wald, was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. Wald became a nurse and Inspired by the work of Jane Addams and Ellen Starr at Hull House in Chicago, she joined Mary Brewster to establish the Henry Street Settlement in New York City in 1893.

The Settlement expanded its range of services to meet the needs of the local community. This included nursing, the establishment of clubs, a savings bank, a library and vocational training for young people. By 1903 Wald was organizing 18 district nursing service centres that overall treated 4,500 patients in New York. Over the next few years Wald promoted the idea of building public playgrounds and cultural institutions in working class areas.

Wald was an active campaigner for civil rights and insisted that all Henry Street classes were racially integrated. In 1909 helped to establish the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People. She also took part in the protests against the film Birth of a Nation that celebrated the Ku Klux Klan and its belief in white supremacy.

A committed pacifist, Wald and Fanny Garrison Villard led a parade of 1200 women down Fifth Avenue in New York on 29th August, 1914 to protest against the First World War. Wald was also a member of the Woman's Peace Party (WPP) and after the war helped establish the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF).

After the war Wald campaigned for socialist candidates and was closely associated with left-wing radicals such as Emma Goldman. As a result she became a target of the Red Scare campaign that took place in 1919.

Lillian Wald wrote several books about her activities including House on Henry Street (1915) and The Windows on Henry Street (1934). Lillian Wald died in Westport, Connecticut, on 1st September, 1940.

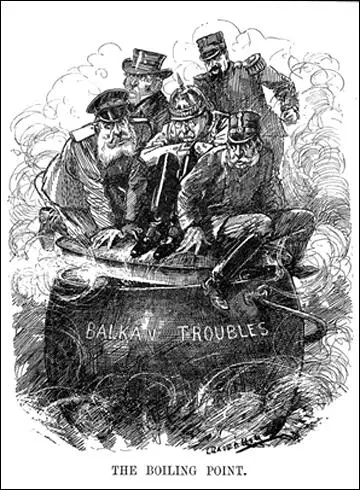

On this day in 1867 Leonard Raven-Hill, the son of a stationer, was born in Bath. He was educated at Bristol Grammar School and the Lambeth School of Art, where a fellow student was F. W. Townsend. He then moved to Paris until being appointed as art editor of Pick-Me-Up. On his return to London he worked as a painter and exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Raven-Hill's drawings first began to appear in Punch Magazine in December, 1895. By 1901 Raven-Hill had joined the staff of the magazine where he succeeded Linley Sambourne as junior political cartoonist under Bernard Partridge. During this period he also illustrated Stalky and Co for Rudyard Kipling and Kipps for H. G. Wells.

Raven-Hill was a strong advocate of British Imperialism, and like his main colleague at Punch Magazine, Bernard Partridge, was a strong supporter of the Conservative Party. During the First World War he produced posters encouraging men to join the armed forces.

After the war he worked for a wide variety of newspapers and magazines including The Daily Graphic, Daily Chronicle, The Strand Magazine, The Sketch, The Pall Mall Gazette and The Windsor Magazine. It has been argued that his failing eyesight made most of his later work disappointing. However, he continued to comment on life in Nazi Germany and the outbreak of the Second World War. Leonard Raven-Hill died at Ryde, Isle of Wight, on 31st March, 1942.

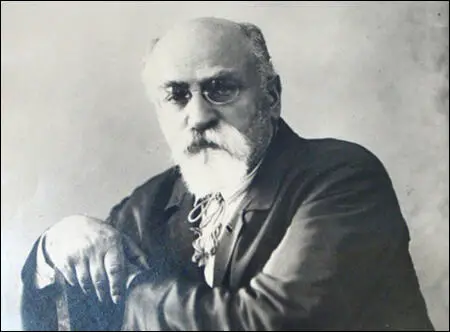

On this day in 1870 David Riazanov was born in Odessa, Ukraine. A rebellious teenager he was expelled from secondary school in 1886. According to Boris Souvarine: "Riazanov began his political life at the age of seventeen by organising a socialist circle in Odessa. One of the very first, it was connected with Plekhanov's League for the Emancipation of Labour, the seedbed of Russian Social Democracy, and undertook to publish the principal works of Marxism in the Russian language."

After serving nearly six years he was placed under police supervision in the city of Kishinev, Bessarabia. In 1900, Riazanov moved to Berlin where he established a small Marxist group called Borbo. He refused to join the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) and in 1903 he developed the concept of permanent revolution. This included the idea that it was possible to miss out the stage of advanced capitalism in Russia before progressing to socialism. This brought him into ideological conflict with Lenin, Julius Martov and George Plekhanov and other leaders of the SDLP. However, later, Lenin was to adopt this theory as his own.

Riazanov, like many Russian revolutionaries, returned from exile following the 1905 Russian Revolution. He was active in the trade union movement in St. Petersburg. After the failure of the uprising Riazanov was arrested and imprisoned. He escaped in 1907 and moved to London. Riazanov carried out detailed research into the writings of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels and his contributions to left-wing newspapers resulted him in being considered one of the world's leading experts on Marxism. During this period he became a close associate of Leon Trotsky and Anatoli Lunacharsky and together they formed the Mezhrayontsky group.

When Tsar Nicholas II abdicated on 13th March, a Provisional Government, headed by Prince George Lvov, was formed. Lvov allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Riazanov returned to St. Petersburg where he helped establish the Russian Railway Union. He was also co-editor of Nashe Slovo, and a member of the Mezhrayontsky group. Other members included Anatoli Lunacharsky, Moisei Uritsky, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko and Alexandra Kollontai.

On 3rd April, 1917, Lenin announced what became known as the April Theses. Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories. Leon Trotsky gave Lenin his full support: "I told Lenin that nothing separated me from his April Theses and from the whole course that the party had taken since his arrival." The two agreed, however, that Trotsky would not join the Bolshevik Party at once, but would wait until he could bring as many of the Mezhrayontsky group into the Bolshevik ranks. Trotsky officially joined the Bolsheviks in July.

In September 1917, Lenin sent a message to the Bolshevik Central Committee via Ivar Smilga. "Without losing a single moment, organize the staff of the insurrectionary detachments; designate the forces; move the loyal regiments to the most important points; surround the Alexandrinsky Theater (i.e., the Democratic Conference); occupy the Peter-Paul fortress; arrest the general staff and the government; move against the military cadets, the Savage Division, etc., such detachments as will die rather than allow the enemy to move to the center of the city; we must mobilize the armed workers, call them to a last desperate battle, occupy at once the telegraph and telephone stations, place our staff of the uprising at the central telephone station, connect it by wire with all the factories, the regiments, the points of armed fighting, etc."

Joseph Stalin read the message to the Central Committee. Nickolai Bukharin later recalled: "We gathered and - I remember as though it were just now - began the session. Our tactics at the time were comparatively clear: the development of mass agitation and propaganda, the course toward armed insurrection, which could be expected from one day to the next. The letter read as follows: 'You will be traitors and good-for-nothings if you don't send the whole (Democratic Conference Bolshevik) group to the factories and mills, surround the Democratic Conference and arrest all those disgusting people!' The letter was written very forcefully and threatened us with every punishment. We all gasped. No one had yet put the question so sharply. No one knew what to do. Everyone was at a loss for a while. Then we deliberated and came to a decision. Perhaps this was the only time in the history of our party when the Central Committee unanimously decided to burn a letter of Comrade Lenin's. This instance was not publicized at the time."

Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Victor Nogin led the resistance to the idea. They argued that an early action was likely to result in the Bolsheviks being destroyed as a political force. As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) has explained why Zinoviev felt strongly about the need to wait: "The experience of the summer (the July Days) had brought him to the conclusion that any attempt at an uprising would end as disastrously as the Paris Commune of 1871; revolution was was inevitable, he wrote at the time of the Kornilov crisis, but the party's task for the time being was to restrain the masses from rising to the provocations of the bourgeoisie."

On 7th October, 1917, Lenin sent out another message to the Bolshevik Central Committee: "In our Central Committee and at the top of our party there is a tendency in favor of awaiting the Congress of Soviets, against an immediate uprising. We must overcome this tendency or opinion. Otherwise the Bolsheviks would cover themselves with shame forever; they would be reduced to nothing as a party. For to miss such a moment and to await the Congress of Soviets is either idiocy or complete betrayal.... To wait for the Congress of Soviets, etc., under such conditions means betraying internationalism, betraying the cause of the international socialist revolution."

Lenin thought the details of an uprising would be simple. "We can launch a sudden attack from three points, from Petrograd, from Moscow, from the Baltic Fleet... We have thousands of armed workers and soldiers in Petrograd who can seize at once the Winter Palace, the General Staff building, the telephone exchange and all the largest printing establishments... The troops will not advance against the government of peace... Kerensky will be compelled to surrender." When it was clear that the Bolshevik Central Committee did not accept Lenin's point of view he issued a political ultimatum: "I am compelled to tender my resignation from the Central Committee, which I hereby do, leaving myself the freedom of propaganda in the lower ranks of the party and at the party congress."

Mikhail Lashevich, a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee, argued strongly against taking action at this time: "The strategic plan proposed by Comrade Lenin is limping on all four legs.... Let's not fool ourselves, comrades. Comrade Lenin has not given us any explanation why we need to do this right now, before the Congress of Soviets. I don't understand it. By the time of the Congress of Soviets the sharpness of the situation will be all the clearer. The Congress of Soviets will provide us with an apparatus; if all the delegates who have come together from all over Russia express themselves for the seizure of power, then it is a different matter. But right now it will only be an armed uprising, which the government will try to suppress."

Riazanov gave cautious support for Lenin. On 14th October he argued at a meeting of the Central Committee of the Soviets: "The move is not being prepared by the Bolsheviks; the move is being prepared by that policy which in the course of seven months of the revolution had done so much for the bourgeoisie and nothing for the masses.... We don't know the day and hour for the move, but we say to the mass of the people: prepare for the decisive struggle for land and peace, for bread and freedom. If as a result of this policy a government of the worker and peasant masses arises, we will be in the first ranks of the insurgents."

On the evening of 24th October, 1917, orders were given for the Bolsheviks began to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Alexander Kerensky had managed to escape from the city.

The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace and arrested the Cabinet ministers.

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Felix Dzerzhinsky (Internal Affairs), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War).

The balloting for the Constituent Assembly began on 25th November and continued until 9th December. Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17). As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie."

Lenin was bitterly disappointed with the result as he hoped it would legitimize the October Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia.

Riazanov disagreed with this policy and as a result of the elections, favoured a coalition government. He also objected to the Brest-Litovsk Treaty and in 1918 he resigned in protest but was later readmitted to the Bolshevik Party. He helped establish the Socialist Academy of Social Sciences and in 1920 and worked alongside such figures as Nikolai Sukhanov and Isaak Rubin. Riazanov wrote at this time: "I am not a Bolshevik, I am not a Menshevik, I am not a Leninist. I am only a marxist, and, as a marxist, I am a communist"

Riazanov attended the 2nd World Congress of the Communist International as a member of the Russian delegation. Victor Serge met him during this period: "I was on very close terms with several of the scientific staff at the Marx-Engels Institute, headed by David Borisovich Riazanov, who had created there a scientific establishment of noteworthy quality. Riazanov, one of the founders of the Russian working-class movement, was, in his sixtieth year, at the peak of a career whose success might appear exceptional in times so cruel. He had devoted a great part of his life to a severely scrupulous inquiry into the biography and works of Marx - and the Revolution heaped honor on him, and in the Party his independence of outlook was respected. Alone, he had never ceased to cry out against the death penalty, even during the Terror, never ceased to demand the strict limitation of the rights of the Cheka and its successor, the GPU. Heretics of all kinds, Menshevik Socialists or Oppositionists of Right or Left, found peace and work in his Institute, provided only that they had a love of knowledge."

David Riazanov remained a critic of Lenin's government. During the Russian Civil War he tirelessly demanded the abolition of the death penalty. Roy A. Medvedev, has pointed out in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) that in May 1921 at the 4th All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions, Riazanov and his friend Maihail Tomsky clashed with Joseph Stalin over the economic policy of the government: "At that meeting D. B. Riazanov sharply criticized the Control Commission (CC) and supported the independence of the trade unions from the Party. He introduced a motion that contradicted the line of the CC, including a demagogic proposal for the payment of wages in goods, which caused great excitement among the delegates. It was attractive because of the sharp drop in the purchasing power of money. A majority of the Communist caucus unexpectedly voted for Riazanov's motion rather than the resolution prepared by the Party's Central Committee. Stalin, who was present, tried to get the motion repealed. But his speech lacked convincing arguments; he spoke in a harsh, irritated tone, and made personal attacks on M. P. Tomskii, Riazanov, and the whole caucus." When Riazanov replied, Stalin, instead of criticizing his argument, shouted: "Shut up, you clown!" Riazanov replied: "Don't make a fool of yourself. Everybody knows that theory is not exactly your field." It has been claimed that this comment resulted in Stalin seeking revenge against Riazanov."

In December 1930, Riazanov's colleague, Isaak Rubin, was arrested by the Soviet secret police and charged with participation in a plot to establish an underground organization called the "Union Bureau of Mensheviks." Rubin's sister later reported: "Rubin's position was tragic. He had to confess to what had never existed, and nothing had: neither his former views; nor his connections with the other defendants, most of whom he didn't even know, while others he knew only by chance; nor any documents that had supposedly been entrusted to his safekeeping; nor that sealed package of documents which he was supposed to have handed over to Riazanov. In the course of the interrogation and negotiations with the investigator, it became clear to Rubin that the name of Riazanov would figure in the whole affair, if not in Rubin's testimony, then in the testimony of someone else. And Rubin agreed to tell the whole story about the mythical package. My brother told me that speaking against Riazanov was just like speaking against his own father. That was the hardest part for him, and he decided to make it look as if he had fooled Riazanov, who had trusted him implicitly. My brother stubbornly kept to this position in all his depositions: Riazanov had trusted him personally and he, Rubin, had fooled trustful Riazanov. No one and nothing could shake him from this position. His deposition of February 21 concerning this matter was printed in the indictment and signed by Krylenko on February 23, 1931. The deposition said that Rubin handed Riazanov the documents in a sealed envelope, and asked him to keep them for a while at the Institute. My brother stressed this position in all his statements before and during the trial. At the trial he gave a number of examples which were supposed to explain why Riazanov trusted him so much."

V. V. Sher was another witness who gave evidence against Riazanov. Victor Serge points out in his book, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "Of course his heretical colleagues were often arrested, and he defended them, with all due discretion. He had access to all quarters and the leaders were a little afraid of his frank way of talking. His reputation had just been officially recognized in a celebration of his sixtieth birthday and his life's work when the arrest of the Menshevik sympathizer Sher, a neurotic intellectual who promptly made all the confessions that anyone pleased to dictate to him, put Riazanov beside himself with rage. Having learnt that a trial of old Socialists was being set in hand, with monstrously ridiculous confessions foisted on them, Riazanov flared up and told member after member of the Politburo that it was a dishonor to the regime, that all this organized frenzy simply did not stand up and that Sher was half-mad anyway."

Roy A. Medvedev, who has carried out a detailed investigation of the case, argued in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) that the Union Bureau of Mensheviks did not exist. "The political trials of the late twenties and early thirties produced a chain reaction of repression, directed primarily against the old technical intelligentsia, against Cadets who had not emigrated when they could have, and against former members of the Social Revolutionary, Menshevik, and nationalist parties."

Isaak Rubin was sentenced to a 5-year term of imprisonment. This testimony of Rubin was used in building a case against Riazanov, Nikolai Sukhanov and other colleagues at the Marx-Engels Institute. Riazanov was dismissed as director of the institute in February 1931, and expelled from the Communist Party. Riazanov was arrested by Cheka but as he refused to confess he did not appear in court and instead was sent into exile to the the city of Saratov. Over the next six years he worked at the university library.

Boris Souvarine pointed out: "Riazanov was arrested, imprisoned and deported without any form of trial, the work of the Institute was suspended, and almost all of his collaborators were recalled. An omnipotent and autocratic power had condemned him without trial, and without even allowing him to be heard. The last refuge of social science and marxist culture in Russia had ceased to exist. With this barbarous exploit, the dictatorship of the secretariat has perhaps delivered a mortal blow at a great and disinterested servant of the proletariat and of communism. It has surely lost a precious source of knowledge, and destroyed a study centre unique in the world. But it may at least at the same time have dispelled the last mirage capable of creating illusions abroad, and by revealing its real nature, proved the absolute incompatibility between post-Leninist Bolshevism and marxism."

In 1937 David Riazanov was arrested again and accused of being involved in a plot with Leon Trotsky against Joseph Stalin. After a brief secret trial he was executed on 21st January, 1938. Riazanov was posthumously rehabilitated by Nikita Khrushchev in 1958. This was confirmed by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1989.

On this day in 1910 Karl Lueger, the son of Leopold Lueger, an usher at the Vienna Polytechnic, was born at Wieden on 24th October, 1844. He attended Theresianische Ritterakademie before studying law at the University of Vienna, receiving his doctorate in 1870. During this period he joined the Catholic Student Association.

Lueger established a law office in Vienna in 1874 and established a reputation for representing the interests of the working class. The following year he was elected to Vienna's City Council. Lueger advocated an early form of "fascism". This included a radical German nationalism (meaning the primacy and superiority of all things German), social reform, anti-socialism and anti-semitism. In one speech in 1890 Lueger commented that the "Jewish problem" would be solved, and a service to the world achieved, if all Jews were placed on a large ship to be sunk on the high seas.

In 1891 Lueger helped to establish the Christian Social Party (CSP). Deeply influenced by the philosophy of the Catholic social reformer, Karl von Vogelsang, who had died the previous year. There were many priests in the party, which attracted many votes from the tradition-bound rural population. It was seen as a rival to Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) that was portrayed by Lueger as an anti-religious party.

After the 1895 elections for the Vienna's City Council the Christian Social Party took political power from the ruling Liberal Party. Lueger was selected to became mayor of Vienna but this was overruled by Emperor Franz Joseph who considered him a dangerous revolutionary. After personal intercession by Pope Leo XIII his election was finally sanctioned in 1897.

Lueger was a zealous Catholic, and wished to “capture the university” for the Church. He made it clear that he would have neither Social Democrats nor Pan-Germans nor Jews in the municipal administration. Lueger did introduce important social reforms. This included the extension of the public water supply, the municipalization of gas and electricity works as well as the establishment of a public transport system. He also built parks and gardens, and hospitals and schools.

In a speech in 1899, Lueger claimed that Jews were exercising a "terrorism, worse than which cannot be imagined" over the masses through the control of capital and the press. It was a matter for him, he continued, "of liberating the Christian people from the domination of Jewry". On other occasions he described the Jews as "beasts of prey in human form". Lueger added that anti-semitism would "perish when the last Jew perished".

Adolf Hitler first arrived in Vienna in 1907 Lueger was the dominant force in political life. Ian Kershaw, the author of Hitler 1889-1936 (1998) has argued: "The rise of Lueger's Christian Social Party made a deep impression on Hitler... he came increasingly to admire Lueger.... With a heady brew of populist rhetoric and accomplished rabble-rousing. Lueger soldered together an appeal to Catholic piety and the economic self-interest of the German-speaking lower-middle classes who felt threatened by the forces of international capitalism, Marxist Social Democracy, and Slav nationalism... The vehicle used to whip up the support of the disparate targets of his agitation was anti-semitism, sharply on the rise among artisanal groups suffering economic downturns and only too ready to vent their resentment both on Jewish financiers and on the growing number of Galician back-street hawkers and pedlars."

Konrad Heiden, a young Jewish journalist who investigated Hitler's time in Vienna, later commented: "A much greater development was that of a second anti-Semitic movement embracing the mass of the German petty-bourgeoisie and parts of the working class, but also having many supporters among the numerous Czech population of Vienna: this was the Christian Social Party, led by an intellectual who had arisen from modest circumstances: Doctor Karl Lueger. A strong personality, a powerful tribune of the people, a party despot who made himself the all-powerful mayor of Vienna. Young Hitler admired him greatly, handed out leaflets for the Christian Social Party, stood on street corners and made speeches. Lueger had the young sons of his supporters parade through the streets with music, banners, and the beginnings of a uniform."

William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964), agrees with Heiden: "There was another mistake of the Pan-Germans which Hitler was not to make. That was the failure to win over the support of at least some of the powerful, established institutions of the nation - if not the Church, then the Army, say, or the cabinet or the head of state. Unless a political movement gained such backing, the young man saw, it would be difficult if not impossible for it to assume power.... There was one political leader in Vienna in Hitler's time who understood this, as well as the necessity of building a party on the foundation of the masses. This was Dr Karl Lueger, the burgomaster of Vienna and leader of the Christian Social Party, who more than any other became Hitler's political mentor, though the two never met."

Adolf Hitler was also impressed with the way Lueger made use of the Catholic Church: "His policy was fashioned with infinite shrewdness". Lueger "was quick to make use of all available means for winning the support of long-established institutions, so as to be able to derive the greatest possible advantage for his movement from those old sources of power". Hitler stated that Lueger was "the greatest German mayor of all times... a statesman greater than all the so-called 'diplomats' of the time... If Dr Karl Lueger had lived in Germany he would have been ranked among the great minds of our people."

Hitler claimed in Mein Kampf (1925) that it was Lueger who helped develop his anti-semitic views: "Dr. Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party. When I arrived in Vienna, I was hostile to both of them. The man and the movement seemed reactionary in my eyes. My common sense of justice, however, forced me to change this judgment in proportion as I had occasion to become acquainted with the man and his work; and slowly my fair judgment turned to unconcealed admiration... For a few hellers I bought the first anti-Semitic pamphlets of my life.... Wherever I went, I began to see Jews, and the more I saw, the more sharply they became distinguished in my eyes from the rest of humanity. Particularly the Inner City and the districts north of the Danube Canal swarmed with a people which even outwardly had lost all resemblance to Germans. And whatever doubts I may still have nourished were finally dispelled by the attitude of a portion of the Jews themselves."

Hitler goes onto argue: "By their very exterior you could tell that these were no lovers of water, and, to your distress, you often knew it with your eyes closed. Later I often grew sick to my stomach from the smell of these caftan-wearers. Added to this, there was their unclean dress and their generally un-heroic appearance. All this could scarcely be called very attractive; but it became positively repulsive when, in addition to their physical uncleanliness, you discovered the moral stains on this 'chosen people.' In a short time I was made more thoughtful than ever by my slowly rising insight into the type of activity carried on by the Jews in certain fields. Was there any form of filth or profligacy, particularly in cultural life, without at least one Jew involved in it? If you cut even cautiously into such an abscess, you found, like a maggot in a rotting body, often dazzled by the sudden light - a kike! What had to be reckoned heavily against the Jews in my eyes was when I became acquainted with their activity in the press, art, literature, and the theater."

Lueger's main political opponent at the time was Victor Adler, the leader of the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP). Lueger attacked Adler for his Jewish origins and his Marxism. According to Rudolf Olden Hitler shared Lueger's dislike of Adler even though his "genius, tact and kindheartedness gained him admirers among all classes". As Ian Kershaw pointed out: "Victor Adler... was committed to a Marxist programme... Internationalism, equality of individuals and peoples, universal, equal and direct suffrage, fundamental labour and union rights, separation of church and state, and a people's army were what the Social Democrats stood for. It was little wonder that the young Hitler, avid supporter of pan-Germanism, hated the Social Democrats with every fibre of his body." Karl Lueger, who never married, died of diabetes mellitus on 10th March 1910.

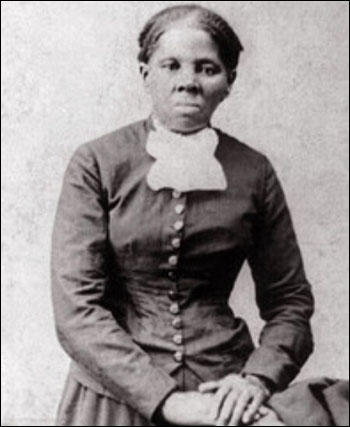

On this day in 1913 Harriet Tubman, died. Harriet Tubman was born a slave in Dorchester County, Maryland in about 1820. In 1848 Tubman decided to try and escape from her plantation. Her husband, John Tubman, refused to go with her as he believed it was too dangerous. Her two bothers accompanied her but later they became frightened and decided to return to the plantation.

Tubman made her way north by the Underground Railroad. Later, Tubman returned to rescue the rest of the family. This was the first of 19 secret trips she made to the South, during which she guided more than 300 slaves to freedom. Tubman's activities became so notorious that plantation owners offered a $40,000 reward for her capture.

According to Thomas Garrett: "No slave who placed himself under her care, was ever arrested that I have heard of; she mostly had her regular stopping places on her route; but in one instance, when she had several stout men with her, some 30 miles below here, she said that God told her to stop, which she did; and then asked him what she must do. He told her to leave the road, and turn to the left; she obeyed, and soon came to a small stream of tide water; there was no boat, no bridge; she again inquired of her Guide what she was to do. She was told to go through. It was cold, in the month of March; but having confidence in her Guide, she went in; the water came up to her armpits; the men refused to follow till they saw her safe on the opposite shore. They then followed, and, if I mistake not, she had soon to wade a second stream; soon after which she came to a cabin of colored people, who took them all in, put them to bed, and dried their clothes, ready to proceed next night on their journey."

Wendell Phillips was told by John Brown about the importance of her activities: "He (John Brown) then went on to recount her labors and sacrifices in behalf of her race. After that, Harriet spent some time in Boston, earning the confidence and admiration of all those who were working for freedom. With their aid she went to the South more than once, returning always with a squad of self-emancipated men, women, and children, for whom her marvelous skill had opened the way of escape."

A supporter of John Brown and his insurrection at Harper's Ferry in 1859, she was so disappointed by its failure that she began an intensive speaking tour of the North. In her speeches she not only advocated an end to slavery but argued for women's suffrage.

During the American Civil War Tubman worked as a nurse, scout and an intelligence agent for the Union Army. Tubman's former activities as a conductor on the Underground Railroad made her especially useful as a scout during the conflict. Wendell Phillips wrote that " After the war broke out, she was sent with endorsements from Governor Andrew and his friends to South Carolina, where in the service of the Nation she rendered most important and efficient aid to our army. In my opinion there are few captains, perhaps few colonels, who have done more for the loyal cause since the war began, and few men who did before that time more for the colored race, than our fearless and most sagacious friend, Harriet."

Frederick Douglass wrote to Harriet Tubman in 1868: "The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day - you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt God bless you has been your only reward. The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism."

With the help of Sarah Hopkins Bradford, she wrote her autobiography, Harriet Tubman, the Moses of Her People, (1869). With the royalties from the book and a small pension from the United States Army she purchased a house in Auburn, New York and turned it into a home for the aged and needy.

On this day in 1914 Mary Richardson attacked the Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery. She later described what happened: "I dashed up to the painting. My first blow with the axe merely broke the protective glass. But, Of course, it did more than that, for the detective rose with his newspaper still in his hand and walked round the red plush seat, staring up at the skylight which was being repaired. The sound of the glass breaking also attracted the attention of the attendant at the door who, in his frantic efforts to reach me, slipped on the highly polished floor and fell face downward. And so I was given time to get in a further four blows with my axe before I was, in turn, attacked."

The Manchester Guardian reported the following day: "At the National Gallery, yesterday morning, the famous Rokeby Venus, the Velasquez picture which eight years ago was bought for the nation by public subscription for £45,000, was seriously damaged by a militant suffragist connected with the Women's Social and Political Union... The woman, producing a meat chopper from her muff or cloak, smashed the glass of the picture, and rained blows upon the back of the Venus. A police officer was at the door of the room, and a gallery attendant also heard the smashing of the glass. They rushed towards the woman, but before they could seize her she had made seven cuts in the canvas." Later she revealed that she hated the way nude paintings were "gloated over by men".

On this day in 1937 Yevgeny Zamyatin died. Zamyatin was born in Lebedyan, Russia, on 20th January, 1884. The son of a teacher, Zamyatin trained as a naval engineer at St Petersburg. While a student joined the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). He later wrote: "To be a Bolshevik in those years meant following the path of greatest resistance, so I was a Bolshevik then."

Zamyatin's support of the Bolsheviks resulted in him being arrested and sent into exile. He returned during the 1905 Revolution and joined the student demonstrations against Nicholas II. Zamyatin was arrested, badly beaten and sent to Spalernaja Prison where he had to endure several months of solitary confinement.

After graduating Zamyatin became a lecturer at the Department of Naval Architecture. He wrote several articles on ship construction for journals such as The Ship and Russian Navigation. He also wrote fiction and in 1913 published the novel A Provincial Tale. This was followed by At The World's End (1914), a satire on military life. This upset the censors and Zamyatin was brought to trial but was acquitted. However, the book was banned and all copies were destroyed.

During the First World War Zamyatin was sent to England to supervise the building of Russian icebreakers. He returned to Russia after the October Revolution. Although initially a supporter of the Bolsheviks he began to question the new government's attempt to control the arts.

Zamyatin switched his support to the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and published a series of political fables in Delo Naroda (The People's Concern), a newspaper run by Victor Chernov. He also wrote for Novaya Zhizn (New Life) a journal funded and edited by Maxim Gorky. In one of these articles he attacked the Soviet government and its Red Terror.

In 1923 Zamyatin published Fires of St. Dominic, a book about the Spanish Inquisition, that parallels the activities of the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. He also wrote a series of plays including the popular Attilla. It was through his work with World Literature that Zamyatin discovered the science fiction of H. G. Wells. This inspired him to write the novel We. The first anti-utopian novel ever written, it is a satire on life in a collectivist state in the future. People in this new society called One State, have numbers rather than names, wear identical uniforms and live in buildings built of glass. The people are ruled by the Benefactor and policed by the Guardians. One State is surrounded by a wall of glass and outside is an untamed green jungle.

Ignoring warnings about the dangers of what he was doing, Zamyatin published the essay, I Am Afraid, where he argued that the attitude of those in authority was stifling creative literature. Zamyatin argued that "the only weapon worthy of man is the word." He added "fortunately, all truths are false: the essence of the dialectical process is that today's truths become errors tomorrow."

In 1919 Yevgeny Zamyatin was recruited by Maxim Gorky to work with him on his World Literature project. It was the task of Gorky, Zamyatin, Alexander Blok, Nikolai Gumilev, and other members of the editorial board to select, translate and publish non-Russian literary works. Each volume was to be annotated, illustrated, and supplied with an introductory essay.

Zamyatin continued to write fiction and literary criticism and in 1921 his work inspired the creation of Serapion Brothers. The group argued for greater freedom and variety in literature. Members included Nickolai Tikhonov, Mikhail Slonimski, Vsevolod Ivanov and Konstantin Fedin.

In 1923 Zamyatin published Fires of St. Dominic, a book about the Spanish Inquisition, that parallels the activities of the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. He also wrote a series of plays including the popular Attilla. It was through his work with World Literature that Zamyatin discovered the science fiction of H. G. Wells. This inspired him to write the novel We. The first anti-utopian novel ever written, it is a satire on life in a collectivist state in the future. People in this new society called One State, have numbers rather than names, wear identical uniforms and live in buildings built of glass. The people are ruled by the Benefactor and policed by the Guardians. One State is surrounded by a wall of glass and outside is an untamed green jungle.

The hero of We is D-503, a mathematician who is busy building Integral, a gigantic spaceship which will eventually go to other planets to spread the joy of the One State. D-503 is happy with his life until he falls in love with I-330, a member of Mephi, a revolutionary organization living in the jungle. D-503 now joins the plot to take over Integral and use it as a weapon to destroy One State. However, the conspirators are arrested by the Guardians and the Benefactor decides that action must be taken to prevent further revolts. D-503 like the rest of the people living in One State, is forced to undergo the Great Operation, which destroys the part of the brain which controls passion and imagination.

Zamyatin secretly distributed copies of We through literary circles. He was warned by friends that attempts to publish the book in the Soviet Union would led to his arrest and possible execution. Zamyatin knew that he could not be published in the Soviet Union but he managed to smuggle a copy of his manuscript abroad. An English translation of the novel was published in the United States in 1924. Three years later a Russian language edition began to circulate in Eastern Europe.

The publication of We brought fierce criticism from the Soviet Writers' Union. He responded by resigning with the comment that "I find it impossible to belong to a literary organization which, even if only indirectly, takes a part in the persecution of a fellow member."

Zamyatin's plays were banned from the theatre and any books that had been published in the Soviet Union were confiscated. Zamyatin described these events as a "writer's death sentence" and wrote to Joseph Stalin requesting to emigrate claiming that "no creative activity is possible in an atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year." He bravely added: " Regardless of the content of a given work, the very fact of my signature has become a sufficient reason for declaring the work criminal. Of course, any falsification is permissible in fighting the devil. I beg to be permitted to go abroad with my wife with the right to return as soon as it becomes possible in our country to serve great ideas in literature without cringing before little men".

It appeared only a matter of time before Zamyatin would be arrested and imprisoned. However, in 1931 Maxim Gorky managed to use his influence over Joseph Stalin to allow Zamyatin to leave the Soviet Union.

Yevgeny Zamyatin settled in France where he wrote screenplays such as Anna Karenina. He also wrote an unfinished novel, The Scourge of God, a satire on the Russian Revolution. Yevgeni Zamyatin died of a heart attack in Paris on 10th March, 1937. We, although never published in the Soviet Union, deeply influenced other novels about the future such as Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell.

On this day in 1941 Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour, makes a speech about women's war work. "Making an urgent appeal to women to come forward for war work mainly in shell-filling factories, Mr. Bevin said he did not want them to wait for registration to take effect. He wanted a big response now, especially by those who might not have been in employment before. There was a tendency to hang back and wait for instructions. If he could get the first 100,000 women to come forward in the next fortnight it would be priceless... In districts where married women had been in the habit of doing the work the Government had decided to assist them so far as the minding of children was concerned. They had arranged for the rapid expansion through local authorities of day nurseries and they were asking local authorities to prepare immediately a register of minders. The married woman would pay only what she paid in pre-war days - about sixpence a day - and the Government would pay an additional sixpence a day for looking after the children."

One vital need was for women to work in munitions factories. Other women were conscripted to work in tank and aircraft factories, civil defence, nursing, transport and other key occupations. This involved jobs such as driving trains and operating anti-aircraft guns, that had been traditionally seen as 'men's work'.

Women could choose to join one of the auxiliary services - Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS), the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) or the Women's Transport Service (FANY). Women in the ATS served as volunteers with the British Army until given full military status in July 1941.

Women also joined the Women's Voluntary Service (WVS) to help in supplying a wide variety of emergency services at home. Another option was to become a member of the Women's Land Army and help on British farms. By 1943 around 90 per cent of single women and 80 per cent of married women were involved in war work.

Provision was made for women to object to the National Service Act on moral grounds. Of the 6000 people to go on the conscientious objectors register, around 2000 were women. About 500 women were prosecuted for a range of offences, and more than 200 of them were imprisoned.

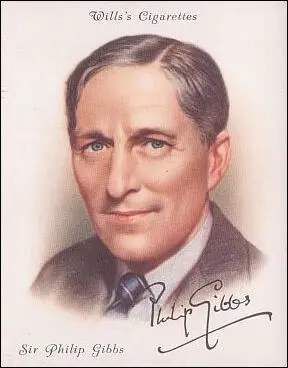

On this day in 1962 Philip Gibbs died. Philip Gibbs, the fifth son of Henry James Gibbs, a civil servant at the Board of Education, and Helen Hamilton, was born in London in 1877. Mainly educated at home by his parents, Gibbs was determined to became a writer and at seventeen had his first article published by the Daily Chronicle. Gibbs worked for the publishing house Cassell and his first book, Founders of the Empire appeared in 1899.

In 1902 Alfred Harmsworth appointed Gibbs as literary editor of the Daily Mail. This was followed by periods with the Daily Express and the Daily Chronicle. He also joined with J. L. Hammond, Henry Brailsford and Leonard Hobhouse to produce a new Liberal newspaper called the Tribune. The newspaper was not a success and Gibbs began writing novels. The Street of Adventure (1909) described his early years as a journalist in London. His next book, Intellectual Mansions (1910), dealt sympathetically with the Suffragette struggle for the vote.

In 1913 Gibbs went to Germany to report the growing tensions between the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente. His articles forecasting a peace agreement between the two groups proved incorrect and in 1914 was sent to France to report the First World War. The War Office decided to control the news that appeared in British newspapers. When Gibbs continued to report the war he was arrested and returned to England.

In 1915 Gibbs was one of the five journalists selected by the government to become official war correspondents with the British Army. Gibbs had to submit all his reports to the censor, C. E. Montague, the former leader writer with the Manchester Guardian.

As well as writing articles about the war for the Daily Chronicle and the Daily Telegraph, Gibbs wrote several books on the conflict: The Soul of the War (1915), The Battle of the Somme (1917), From Bapaume to Passchendaele (1918) and The Realities of War (1920). Like the other four official British journalists in the war, Gibbs was awarded a knighthood in 1920.

In 1919 Gibbs undertook a very successful lecture tour of the United States. Later that year, Gibbs became the first journalist ever to obtain an interview with the Pope. Gibbs was a Roman Catholic and in 1920 resigned from the Daily Chronicle in protest at the newspaper's support of David Lloyd George's policy of reprisals in Ireland.

Over the next fifteen years Gibbs worked as a freelance journalist. He also published several books on European politics including Since Then (1930), European Journey (1934), England Speaks (1935), Ordeal in England (1937) and Across the Frontiers (1938).

On the outbreak of the Second World War he worked briefly as a foreign reporter for the Daily Sketch. Later he was invited to work for the Ministry of Information in the United States. After the war failing eyesight prevented Gibbs from continuing his work as a journalist.

Philip Gibbs first book of reminiscences, Adventures in Journalism, appeared in 1923. In his later years, he published three more volumes of autobiography: The Pageant of the Years (1946), Crowded Company (1949) and Life's Adventure (1957).

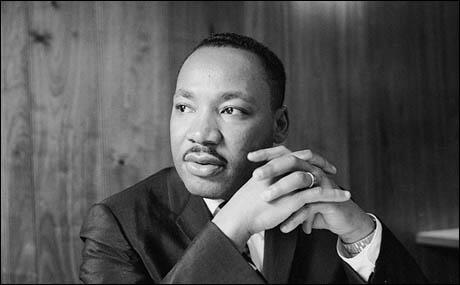

On this day in 1969 James Earl Ray pleads guilty to assassinating Martin Luther King Jr. He was sent to jail for ninety-nine years. People close to King were convinced that the government was behind the assassination. Ralph Abernathy, who replaced King as head of the SCLC, claimed that he had been killed “by someone trained or hired by the FBI and acting under the orders from J. Edgar Hoover”. Whereas James Lawson, the leader of the strike in Memphis remarked that: “I have no doubt that the government viewed all this (the Poor People’s Campaign and the anti-Vietnam War speeches) seriously enough to plan his assassination.”

William F. Pepper, who was to spend the next forty years investigating the death of Martin Luther King, discovered evidence that Military Intelligence was involved in the assassination. In his book, Orders to Kill, Pepper names members of the 20th Special Forces Group (SFG) as being part of the conspiracy.

Even the Deputy Director of the FBI, William C. Sullivan, who led the investigation into the assassination, believed that there was a conspiracy to kill King. In his autobiography published after his death, Sullivan wrote: “I was convinced that James Earl Ray killed Martin Luther King, but I doubt if he acted alone… Someone, I feel sure, taught Ray how to get a false Canadian passport, how to get out of the country, and how to travel to Europe because he would never have managed it alone. And how did Ray pay for the passport and the airline tickets?” Sullivan also admits that it was the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and not the FBI who successfully tracked Ray down to London.

In a television interview from prison that took place in 1988, James Earl Ray claimed the FBI agents threatened to jail his father and one of his brothers if he did not confess to King’s murder. Ray added that he had been framed to cover up an FBI plot to kill King.

However, there is evidence that it was another organization that was involved in the assassination of Martin Luther King. According to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, military intelligence became very interested in the activities of King after he began making speeches against the Vietnam War. In a report published in 1972, the committee claimed that in the spring of 1968 King’s organization was “infiltrated by the 109 th, 111 th and 116 th Military Intelligence Groups.” In his book, An Act of State, the lawyer, William F. Pepper points out that the committee was surprised when it discovered that military intelligence appeared to be very interested in where King was “staying in various cities, as well as details concerning housing facilities, offices, bases of operations, churches and private homes.” The Senate Judiciary Subcommittee commented: “Why such information was sought has never been explained.”