On this day on 5th March

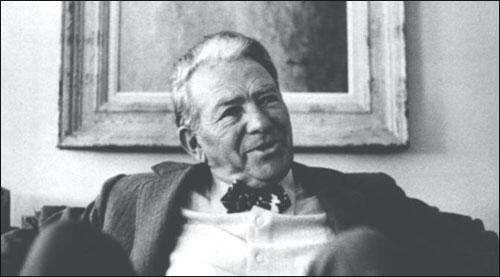

On this day in 1853 Howard Pyle was born in Wilmington, Delaware on 5th March, 1853. He studied at the Arts Student League in New York City and the Pennsylvania Academy.

Pyle contributed to a number of magazines including Harper's Monthly and Scribner's Magazine. He also illustrated books such as The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883) and The Book of Pirates (1902).

Peter Crimmins has claimed that during this period Pyle invented the iconic look of the mythical pirate. "Pyle blended the look of a 16th century sailor with a Spanish Gypsy, with distinct accouterments: a headscarf, a gold earring, and a long sash around the waist. But a real sailor would never wear those things."

Pyle has been described as the "father of American illustration" because of the enormous influence his work had on other artists. Pyle taught at the Arts Student League, the Drexel Institute, and his own art schools at Chadd's Ford and Wilmington. His students included Maxfield Parrish, Newell Convers Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, Olive Rush, Ethel Franklin Betts and Philip R. Goodwin. mith.

Howard Pyle died in Florence of a kidney infection on 9th November, 1911.

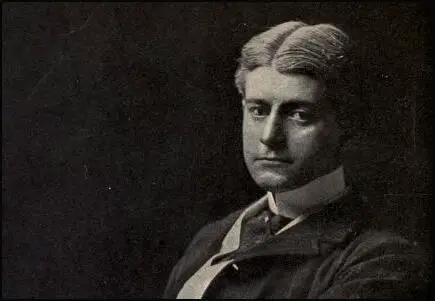

On this day in 1870 Benjamin Franklin Norris was born in Chicago. At the age of 14 Norris and his family moved to San Francisco. After studying at San Francisco University (1890-94) Norris travelled to South Africa where he attempted to establish himself as a travel writer. He wrote about the Boer War for the San Francisco Chronicle but was deported from the country after being captured by the Boer Army.

Norris returned to San Francisco where he joined the staff of the magazine, The Wave. A sea story written by Norris was serialized in the magazine and was later published as a novel, Moran of the Lady Letty (1898). During this period he worked for the publishers Doubleday.

Norris continued to work as a journalist and reported the Spanish-American War for McClure's Magazine. This was followed by a couple of novels, McTeague: A Story of San Francisco (1899) and A Man's Woman (1900). Norris, who had been greatly influenced by the work of Emile Zola, also began work on a trilogy, The Epic of Wheat. The first book, The Octopus (1901), described the struggle between farming and railroad interests in California. In August 1902, Everybody's Magazine published an article by Norris, A Deal in Wheat, exposing corrupt business dealings in agriculture.

William Dean Howells was a great supporter of the work of Frank Norris: "What Norris did, not merely what he dreamed of doing, was of vaster frame, and inclusive of imaginative intentions far beyond those of the only immediate contemporary to be matched with him, while it was of as fine and firm an intellectual quality, and of as intense and fusing an emotionality. In several times and places, it has been my rare pleasure to bear witness to the excellence of what Norris had done, and the richness of his promise. The vitality of his work was so abundant, the pulse of health was so full and strong in it, that it is incredible it should not be persistent still."

Frank Norris died of peritonitis following an appendix operation on 25th October, 1902. He was only 32. He is buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California. The second book in the trilogy, The Pitt, about the manipulation of the wheat market, was published posthumously in 1903. The third part, The Wolf, was never written.

Also published posthumously was The Responsibility of the Novelist (1903). The book argues for naturalistic writing based on actual experience and observation. This book, and his novels, influenced a generation of writers including Upton Sinclair, who argued: "Frank Norris had a great influence upon me because I read The Octopus when I was young and knew very little about what was happening in America. He showed me a new world, and he also showed me that it could be put in a novel."

Floyd Dell was another writer who was converted to socialism by Norris' books: "Frank Norris's novel, The Octopus stirred my mind. And that spring, down in a small park near my home, I heard a man make a Socialist speech to a small and indifferent crowd. Afterwards I talked to him; he was a street-sweeper.... And my long-slumbering Socialism woke up." Other writers who claimed that they were deeply influenced by the work of Norris include David Graham Phillips, Theodore Dreiser, Charles Edward Russell and Sinclair Lewis.

On this day in 1871 political philosopher Rosa Luxemburg, the youngest of five children of a lower middle-class Jewish family was born in Zamość, in the Polish area of Russia. A disease in early life kept her in bed for a whole year. It was wrongly treated as tuberculosis of the bone and caused irreparable damage.

On 4th August, 1914, Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter."

John Peter Nettl claims that two left-wing members of the SDP, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, were horrified by these events. They had great hopes that the SDP, the largest socialist party in the world with over a million members, would oppose the war: "Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration and were at one moment near to suicide. Together they tried on 2 and 3 August to plan an agitation against the war; they contacted 20 SPD members with known radical views, but they got the support of only Liebknecht and Mehring... Rosa sent 300 telegrams to local officials who were thought to be oppositional, asking their attitude to the vote in the Reichstag and inviting them to Berlin for an urgent conference. The results were pitiful."

Rosa Luxemburg joined forces with Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Hugo Eberlein to campaign against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Clara Zetkin was initially reluctant to join the group. She argued: "We must ensure the broadest relationship with the masses. In the given situation the protest appears more as a personal beau geste than a political action... It is justified and nice to say that everything is lost, except one's honour. If I wanted to follow my feelings, then I would have telegraphed a yes with great pleasure. But now we must more than ever think and act coolly."

However, by September, 1914, Zetkin was playing a significant role in the anti-war movement. She co-signed with Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Mehring, letters that appeared in socialist newspapers in neutral countries condemning the war. Above all Zetkin used her position as editor-in-chief of the Die Gleichheit (Equality) and as Secretary of the Women's Secretariat of the Socialist International to propagate the positions of the anti-war movement.

Clara Zetkin who later recalled: "The struggle was supposed to begin with a protest against the voting of war credits by the social-democratic Reichstag deputies, but it had to be conducted in such a way that it would be throttled by the cunning tricks of the military authorities and the censorship. Moreover, and above all, the significance of such a protest would doubtless be enhanced, if it was supported from the outset by a goodly number of well-known social-democratic militants."

Karl Liebknecht continued to make speeches in public about the war: "The war is not being waged for the benefit of the German or any other peoples. It is an imperialist war, a war over the capitalist domination of the world market... The slogan 'against Tsarism' is being used - just as the French and British slogan 'against militarism' - to mobilise the noble sentiments, the revolutionary traditions and the hopes of the people for the national hatred of other peoples."

In May 1915, Liebknecht published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued that: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity."

In December, 1915, 19 other deputies joined Karl Liebknecht in voting against war credits. The following year a series of demonstrations took place. Some of these were "spontaneous outbursts by unorganised groups of people, usually women: anger would flare when a shop ran out of food, or put its prices up, or when rations were suddenly cut." These demonstrations often led to bitter clashes between workers and the police.

Rosa Luxemburg continued to protest against Germany's involvement in the war and on the 19th February, 1915, she was arrested. In a letter to her friend, Mathilde Jacob, she described her first day in prison: "Incidentally, so that you don't get any exaggerated ideas about my heroism, I'll confess, repentantly, that when I had to strip to my chemise and submit to a frisking for the second time that day, I could barely hold back the tears. Of course, deep inside, I was furious with myself at such weakness, and I still am. Also on the first evening, what really dismayed me was not the prison cell any my sudden exclusion from the land of the living, but the fact that I had to go to bed without a night-dress and without having combed my hair."

As a political prisoner she was allowed books and writing materials. With the help of Mathilde Jacob she was able to smuggle out articles and pamphlets she had written to Franz Mehring. In April 1915, Mehring published some of this material in a new journal, Die Internationale. Other contributors included Clara Zetkin, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker and Heinrich Ströbel. The journal included articles by Mehring on the attitude of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to the problem of war and Zetkin dealt with the position of women in wartime. The main objective of the journal was to criticise the official policy of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) towards the First World War.

In the first edition Luxemburg contributed an article on the way the SDP reacted to the outbreak of the war. "Faced with this alternative, which it had been the first to recognize and bring to the masses’ consciousness, Social Democracy backed down without a struggle and conceded victory to imperialism. Never before in the history of class struggles, since there have been political parties, has there been a party that, in this way, after fifty years of uninterrupted growth, after achieving a first-rate position of power, after assembling millions around it, has so completely and ignominiously abdicated as a political force within twenty-four hours, as Social Democracy has done. Precisely because it was the best-organized and best-disciplined vanguard of the International, the present-day collapse of socialism can be demonstrated by Social Democracy’s example."

Luxemburg also wrote a pamphlet entitled The Crisis of German Social Democracy during this period. She exposed the lies that were told to those men who willingly volunteered to fight in a war that would only last a few weeks: "Mass slaughter has become the tiresome and monotonous business of the day and the end is no closer... Gone is the euphoria. Gone the patriotic noise in the streets... The trains full of reservists are no longer accompanied by virgins fainting from pure jubilation. They no longer greet the people from the windows of the train with joyous smiles.... The cannon fodder loaded onto trains in August and September is moldering in the killing fields of Belgium, the Vosges, and Masurian Lakes where the profits are springing up like weeds. It’s a question of getting the harvest into the barn quickly. Across the ocean stretch thousands of greedy hands to snatch it up. Business thrives in the ruins. Cities become piles of ruins; villages become cemeteries; countries, deserts; populations are beggared; churches, horse stalls. International law, treaties and alliances, the most sacred words and the highest authority have been torn in shreds."

Over the next few months members of this group were arrested for their anti-war activities and spent several short spells in prison. This included Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, Hugo Eberlein, Leo Jogiches, Heinrich Blücher, Paul Levi, Franz Mehring, Julian Marchlewski and Hermann Duncker. On the release of Luxemburg in February 1916, it was decided to establish an underground political organization called Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). The Spartacus League publicized its views in its illegal newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Like the Bolsheviks in Russia, they argued that socialists should turn this nationalist conflict into a revolutionary war.

The group published an attack on all European socialist parties (except the Independent Labour Party): "By their vote for war credits and by their proclamation of national unity, the official leaderships of the socialist parties in Germany, France and England (with the exception of the Independent Labour Party) have reinforced imperialism, induced the masses of the people to suffer patiently the misery and horrors of the war, contributed to the unleashing, without restraint, of imperialist frenzy, to the prolongation of the massacre and the increase in the number of its victims, and assumed their share in the responsibility for the war itself and for its consequences."

Eugen Levine was one of the first people to join the Spartacus League. He had been disturbed by the "new wave of national prejudice and chauvinism". His wife, Rosa Levine-Meyer, was shocked when he stated that the war would last "at least eighteen months or two years". This upset his mother who had been convinced by government propaganda that "the war would end by Christmas". Levine told Rosa that the "war would be accompanied by a severe world crisis and revolutionary shocks". He added that during a war "it is easier to convert thousands of workers than one single well-meaning intellectual".

On 1st May, 1916, Rosa Luxemburg, organised a anti-war demonstration on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. It was a great success and by eight o'clock in the morning around 10,000 people assembled in the square. The police charged at Karl Liebknecht who was about to speak to the large crowd. "For two hours after Liebknecht's arrest masses of people swirled around Potsdamer Platz and the neighbouring streets, and there were many scuffles with the police. For the first time since the beginning of the war open resistance to it had appeared on the streets of the capital."

As a member of the Reichstag, Liebknecht had parliamentary immunity from prosecution. When the military judicial authorities demanded that this immunity was removed, the Reichstag agreed and he was placed on trial. On 28th June 1916, Liebknecht was sentenced to two years and six months hard labour. The day Liebknecht was sentenced, 55,000 munitions workers went on strike. The government responded by arresting trade union leaders and having them conscripted into the German Army.

Luxemburg responded by publishing a handbill defending Liebknecht and accusing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) who had removed his parliamentary immunity as being "political dogs". She claimed that: "A dog is someone who licks the boots of the master who has dealt him kicks for decades. A dog is someone who gaily wags his tail in the muzzle of martial law and looks straight into the eyes of the lords of the military dictatorship while softly whining for mercy... A dog is someone who, at his government's command, abjures, slobbers, and tramples down into the muck the whole history of his party and everything it has held sacred for a generation."

Rosa Luxemburg was re-arrested on 10th July, 1916. So also was the seventy-year-old Franz Mehring, Ernest Meyer and Julian Marchlewski. Leo Jogiches now became the leader of the Spartacus League and the editor of its newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Luxemburg, wrote regularly for each edition, sometimes writing three-quarters of a whole issue. She also worked on her book, Introduction to Economics.

As Nicholas II was supreme commander of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia during the First World War. In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way."

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs."

On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Arthur Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges."

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working in Petrograd, with strong left-wing opinions, wrote to his aunt, Anna Maria Philips, claiming that the country was on the verge of revolution: "Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps."

On 10th March, 1917, the Tsar had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that Nicholas II should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed."

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government and a few days later announced that all political prisoners would be allowed to return to their homes. Rosa Luxemburg was delighted to hear about the overthrow of Nicholas II. She wrote to her close friend, Hans Diefenbach: "You can well imagine how deeply the news from Russia has stirred me. So many of my old friends who have been languishing in prison for years in Moscow, St Petersburg, Orel and Riga are now walking about free. How much easier that makes my own imprisonment here!"

In her prison cell she wrote several articles on the overthrow of Nicholas II. "The revolution in Russia has been victorious over bureaucratic absolutism in the first phase. However, this victory is not the end of the struggle, but only a weak beginning." She also condemned the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries who had joined the government. "The coalition ministry is a half-measure which burdens socialism with all the responsibility, without even beginning to allow it the full possibility of developing its programme. It is a compromise which, like all compromises is finally doomed to fiasco."

Luxemburg's fears were realised when Alexander Kerensky became the new prime minister and soon after taking office, he announced the July Offensive. In a long article in Spartakusbriefe she condemned Kerensky's strategy. "Although the Russian Republic professes to be fighting a purely defensive war, in reality it is participating in an imperialist one, and, while it appeals to the right of nations to self-determination, in practice it is aiding and abetting the rule of imperialism over foreign nations."

On 24th October, 1917, Lenin wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already, putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested, the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for delay, when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything."

The Constituent Assembly opened on 18th January, 1918. "The Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries occupied the extreme left of the house; next to them sat the crowded Socialist Revolutionary majority, then the Mensheviks. The benches on the right were empty. A number of Cadet deputies had already been arrested; the rest stayed away. The entire Assembly was Socialist - but the Bolsheviks were only a minority."

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. The following day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. "In all Parliaments there are two elements: exploiters and exploited; the former always manage to maintain class privileges by manoeuvres and compromise. Therefore the Constituent Assembly represents a stage of class coalition.

In the next stage of political consciousness the exploited class realises that only a class institution and not general national institutions can break the power of the exploiters. The Soviet, therefore, represents a higher form of political development than the Constituent Assembly."

Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia. Maxim Gorky, a world famous Russian writer and active revolutionary, pointed out: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished and tens of thousands of workers and peasants... The unarmed revolutionary democracy of Petersburg - workers, officials - were peacefully demonstrating in favour of the Constituent Assembly. Pravda lies when it writes that the demonstration was organized by the bourgeoisie and by the bankers.... Pravda knows that the workers of the Obukhavo, Patronnyi and other factories were taking part in the demonstrations. And these workers were fired upon. And Pravda may lie as much as it wants, but it cannot hide the shameful facts."

Rosa Luxemburg agreed with Gorky about the closing down of the Constituent Assembly. In her book, Russian Revolution, written in 1918 but not published until 1922, she wrote: "We have always exposed the bitter kernel of social inequality and lack of freedom under the sweet shell of formal equality and freedom - not in order to reject the latter, but to spur the working-class not to be satisfied with the shell, but rather to conquer political power and fill it with a new social content. It is the historic task of the proletariat, once it has attained power, to create socialist democracy in place of bourgeois democracy, not to do away with democracy altogether."

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, went to interview Luxemburg while she was in prison in Germany. He later reported: "She asked me if the Soviets were working entirely satisfactorily. I replied, with some surprise, that of course they were. She looked at me for a moment, and I remember an indication of slight doubt on her face, but she said nothing more. Then we talked about something else and soon after that I left. Though at the moment when she asked me that question I was a little taken aback, I soon forgot about it. I was still so dedicated to the Russian Revolution, which I had been defending against the Western Allies' war of intervention, that I had had no time for anything else."

As Paul Frölich pointed out: "She (Rosa Luxemburg) was unwilling to see criticism suppressed, even hostile criticism. She regarded unrestricted criticism as the only means of preventing the ossification of the state apparatus into a downright bureaucracy. Permanent public control, and freedom of the press and of assembly were therefore necessary." Luxemburg argued: "Freedom for supporters of the government only, for members of one party only - no matter how numerous they might be - is no freedom at all. Freedom is always freedom for those who think differently."

Luxemburg then went on to make some predictions about the future of Russia. "But with the suppression of political life in the Soviets must become more and more crippled. Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of the press and of assembly, without the free struggle of opinion, life in every public institution dies down and becomes a mere semblance of itself in which the bureaucracy remains as the only active element. Public life gradually falls asleep. A few dozen party leaders with inexhaustible energy and boundless idealism direct and rule. Among these, a dozen outstanding minds manage things in reality, and an elite of the working class is summoned to meetings from time to time so that they can applaud the speeches of the leaders, and give unanimous approval to proposed resolutions, thus at bottom a cliquish set-up - a dictatorship, to be sure, but not the dictatorship rule.of the proletariat: rather the dictatorship of a handful of politicians, i.e., a dictatorship in the bourgeois sense, in the sense of a Jacobin rule... every long-lasting regime based on martial law leads without fail to arbitrariness, and all arbitrary power tends to deprave society."

On this day in 1879 William Beveridge, the eldest son of a judge in the Indian civil service, was born in Bengal, India, on 5th March 1879. After studying at Charterhouse and Balliol College, Oxford, he became a lawyer.

Beveridge became interested in the social services and wrote about the subject for the Morning Post. In 1909 Beveridge, now considered to be the country's leading authority on unemployment insurance, joined the Board of Trade and helped organize the implementation of the national system of labour exchanges.

In 1909 Beveridge was appointed director of Labour Exchanges and his ideas influenced David Lloyd George and led to the passing of the 1911 National Insurance Act. During the First World War Beveridge was involved in mobilizing and controlling man power.

After the war Beveridge was knighted and made permanent secretary to the Ministry of Food. In 1919 he left the civil service to become director of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Over the next few years he served on several commissions and committees on social policy.

In 1937 Beveridge was appointed Master of University College, Oxford. Three years later, Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour, asked him to look into existing schemes of social security, which had grown up haphazardly, and make recommendations. The report on Social Insurance and Allied Services was published in December 1942.

The report proposed that all people of working age should pay a weekly contribution. In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed, retired or widowed. Beveridge argued that this system would provide a minimum standard of living "below which no one should be allowed to fall".

A second report, Full Employment in a Free Society, appeared in 1944. Later that year, Beveridge, a member of the Liberal Party, was elected to the House of Commons. The following year the new Labour Government began the process of implementing Beveridge's proposals that provided the basis of the modern welfare state.

William Beveridge was created Baron Beveridge of Tuggal and eventually became leader of the Liberals in the House of Lords. William Beveridge, the author of Power and Influence (1953), died on 16th March 1963.

On this day in 1882 Dora Marsden, the daughter of a woollen waste dealer, was born in Marsden, near Huddersfield, on 5th March 1882. Her father left home soon after she was born and the family suffered extreme poverty when she was a child. At the age of 13 she became a probationer and then a pupil-teacher at the local school.

In 1900 she entered Owens College on a Queen's Scholarship. While at the college she met Christabel Pankhurst, Isabella Ford, Teresa Billington and Eva Gore-Booth. Marsden graduated in 1903 with an upper second-class degree and taught in Leeds, Colchester and Manchester.

In 1908 she was appointed headmistress of the Altrincham Pupil-Teacher Centre on a salary of £130 per year. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has pointed out: "The Pupil-Teacher Centre had been set up in the Technical Institute's buildings in George Street, Altrincham, to serve pupils from Altrincham, Knutsford, Ashton-upon-Mersey, and Lynn. Originally it was conceived as a temporary facility until a new secondary school could be built which would also incorporate the training of teachers."

Dora Marsden joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Sylvia Pankhurst described her as "a Yorkshire lass, very tiny with a winsome face, sparkling with animation with laughing golden eyes who had a gift of ready wit and a repartee which, linked with imperturbable good humour made her irresistible to the crowd." By 1908 she was organising demonstrations and speaking at public meetings alongside Christabel Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence.

Rebecca West was also impressed with Dora Marsden: "She (Dora Marsden) was one of the most marvellous personalities that the nation has ever produced. She had, to begin with, the most exquisite beauty of person. She was hardly taller than a child, but she was not just a small woman; she was a perfectly proportioned fairy. She was the only person I have ever met who could so accurately have been described as flower-like that one could have put it down on her passport. And on many other planes she was remarkable."

In March 1909 Marsden resigned as headmistress of the Altrincham Pupil-Teacher Centre to become a paid organiser of the WSPU. Later that month she was arrested with Emily Wilding Davison, Rona Robinson, Patricia Woodlock and Helen Tolson, at a demonstration outside the House of Commons. It was reported in The Times: "the exertions of the women, most of whom were quite young and of indifferent physique, had told upon them and they were showing signs of exhaustion, which made their attempt to break the police line more pitiable than ever." Marsden was sentenced to a month's imprisonment. On her release she became the organiser of the WSPU in North-West Lancashire. Soon afterwards she set up home with Grace Jardine in Southport.

On 4th September 1909 Marsden and Emily Wilding Davison were arrested for breaking windows of a hall in Old Trafford. Two days later she was sentenced to two months' imprisonment in Strangeways. Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "Dora Marsden refused to wear prison clothing and spent her time in prison naked, stripping off her clothes each time an attempt was made to dress her." Eventually she was placed in a strait jacket but managed to wriggle out of it, because, according to the prison governor, "she was a very small woman". After going on hunger-strike she was released.

The following month Dora Marsden, Rona Robinson and Mary Gawthorpe decided to take part in another protest. According to Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990): "Dressed in University gowns they entered the meeting and just before Morley began, raised the question of the recent forced feeding of women in Winson Green. There was an uproar, and the three were quickly bundled out and arrested on the pavement." This time they were released without charge.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote to her in prison: "My dear dear brave and beautiful spirit. I have not words to express what I feel about your wonderful courage and heroism. When I think of your face as I saw it in prison my head is full of reverence for the human spirit... A great force is being generated in this movement. We shall send out stronger and stronger thoughts that will change the course of the world's life... My love to you Dora Marsden, sweetest, gentlest and bravest of suffragettes."

Votes for Women reported on 8th October 1909: "No one who knows these three women graduates, or who glances at the numerous photographs which have appeared in the Press can fail to be struck with the pathos of the incident. Mary Gawthorpe, Rona Robinson and Dora Marsden are all slight, petite women who made their protest in a perfectly quiet and gentle manner... They are women moreover, who have done great credit to their respective Universities... Yet they are treated as "hooligans"; treated with such roughness that all 3 had to have medical attention, and hauled before a police magistrate and charged with disorderly behaviour."

Dora Marsden wanted to stage actions that would involve arrest and subsequently, a hunger strike. However, the WSPU wanted to keep their organisers out of prison and Marsden did not get permission for her planned militant activity. On 24th November, 1909, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence remarked: "We are all so anxious that our organisers should not overwork... I know how carried away by your utter devotion and enthusiasm, but I very earnestly beg you pay all due regard to your health, forgive these little warnings dear, they are promoted by concern and affection for yourself."

Dora Marsden ignored this advice and on 4th December, 1909, she joined Helen Tolson and Winson Etherley in attempting to disrupt a meeting in Southport that was being addressed by Winston Churchill. According to the local newspaper "the security for the meeting was unprecedented in the history of the town". While Churchill was speaking he was interrupted by Marsden. Emmeline Pankhurst later recalled that Marsden was "peering through one of the great porthole openings in the slope of the ceiling, was seen a strange elfin form with wan, childish face, broad brow and big grey eyes, looking like nothing real or earthly but a dream waif."

Dora Marsden provided an account of what happened next in Votes for Women: "A dirty hand was was thrust over my mouth, and a struggle began. Finally I was dropped over a ledge, pushed through the broken window, and we began to roll down the steep sloping roof side. Two stewards, crawling up from the other side, shouted out to the two men who had hold of me." Despite being arrested the local magistrate dismissed all charges against them.

Like many women in the WSPU she began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Marsden and her friends objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organization.

Dora Marsden eventually resigned on 27th January 1911. The WSPU leadership started rumours that she had left over some financial irregularity. Theresa McGrath wrote to her saying "are you aware of the rumours that are about concerning your resignation... that you left the accounts for Southport with a deficiency of £500 and that your resignation itself was owing to a request that you should meet the Treasurer for the purpose of going into the matter."

Marsden now joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL), an organisation formed by Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard. Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. In March 1911 Marsden and her close friend, Grace Jardine, went to work for the WFL newspaper, The Vote.

Dora Marsden attempted to persuade the Women's Freedom League to finance a new feminist journal. When this proposal was refused, Marsden left The Vote. She now joined forces with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe to establish her own journal. Charles Granville, agreed to become the publisher. On 23rd November, 1911, they published the first edition of The Freewoman. The journal caused a storm when it advocated free love and encouraged women not to get married. The journal also included articles that suggested communal childcare and co-operative housekeeping.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

Edwin Bjorkman, writing in the American Review of Reviews, was a great fan of the writing of Dora Marsden: "The writer of The Freewoman editorials has shot into the literary and philosophical firmament as a star of the first magnitude. Although practically unknown before the advent of The Freewoman ... she speaks always with the quietly authoritative air of the writer who has arrived. Her style has beauty as well as force and clarity."

Marsden also attacked the WSPU's strategy of employing militant tactics. She argued that the autocracy of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst prevented independent thought and encouraged followers to become "bondwomen". Marsden went on to suggest "the paramount interest of the WSPU was neither the emancipation of women, nor the vote, but the increase in power of their own organisation." On 7th March, 1912, she wrote: "The Pankhurst party have lost their forthright desire for enfranchisement in their outbalancing desire to raise their own organisation to a position of dictatorship amongst all women's organisations.... The vote was only of secondary importance to the leaders... before every other consideration, political, social or moral comes the aggrandisement of the WSPU itself and the increase of power of their own organisation."

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

Dora argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, the wife of George Bernard Shaw, wrote to Dora Marsden "though there has been much I have not agreed with in the paper", The Freewoman was nevertheless a "valuable medium of self-expression for a clever set of young men and women". However, Olive Schreiner disagreed and argued that the debates about sexuality were inappropriate and revolting in a publication of "the women's movement". Frank Watts wrote a letter to the journal that if women really wanted to discuss sex "then it must be admitted by sane observers that man in the past was exercising a sure instinct in keeping his spouse and girl children within the sheltered walls of ignorance."

Harry J. Birnstingl praised Marsden for raising the subject of homosexuality. He added: "It apparently has never occurred to them that numbers of these women find their ultimate destiny, as it were, among members of their own sex, working for the good of each other, forming romantic - nay passionate - attachments with each other? It is splendid that these women... should suddenly find their destiny in thus working together for the freedom of their own sex. It is one of the most wonderful things of the twentieth century."

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Grace Jardine, Harriet Shaw Weaver, Stella Browne, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Rebecca West, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

By the summer of 1912 Dora Marsden had become disillusioned with the parliamentary system and no longer considered it important to demand women's suffrage: "The politics of the community are a mere superstructure, built upon the economic base... even though Mr. George Lansbury were Prime Minister and every seat in the House occupied by Socialist deputies, the capitalist system being what it is they would be powerless to effect anything more than the slow paced reform of which the sole aim is to make men and masters settle down in a comfortable but unholy alliance... the capitalists own the states. A handful of private capitalists could make England, or any other country, bankrupt within a week."

This article brought a rebuke from H. G. Wells: That you do not know what you want in economic and social organization, that the wild cry for freedom which makes me so sympathetic with your paper, and which echoes through every column of it, is unsupported by the ghost of a shadow of an idea how to secure freedom. What is the good of writing that economic arrangements will have to be adjusted to the Soul of Man if you are not prepared with anything remotely resembling a suggestion of how the adjustment is to be affected?"

Mary Gawthorpe also criticised Dora Marsden for her what she called her "philosophical anarchism". She told her that she "was not really an anarchist at all" but one who believed in rank, with herself at the top. Mary added: "Intellectually you have signed on as a member of the coming aristocracy. Free individuals you would have us be, but you would have us in our ranks... I watch you from week to week governing your paper. You have your subordinates. You say to one go and she goes, to another come, and she comes."

During this period Dora Marsden developed loving relationships with several women, including Rona Robinson, Mary Gawthorpe, Grace Jardine and Harriet Shaw Weaver. In her letters to these women she often referred to them as "sweetheart". Her biographer, Les Garner, has argued: "Whether any of her friendships with women were sexual cannot be determined - certainly they were close and certainly too, Dora's personality and fragile beauty inspired many endearing comments from her friends. She appeared to have a special and unique quality that inspired devotion, if not awe, in some women.... Whether Dora was gay in the modern sense is unknown. There is no concrete evidence to support such a claim."

Mary Gawthorpe had suffered severe internal injuries after being beaten up by stewards at a meeting. She was also imprisoned several times and hunger strikes and force-feeding badly damaged her health and in March 1912, she was unable to continue working as co-editor of The Freewoman. Marsden wrote in the journal that "we earnestly hope that the coming months will see her restored to health". Although Mary was ill, she had not resigned on health grounds, but because of what she claimed was "Dora's bullying" and her "philosophical anarchism". Gawthorpe returned all Dora's letters and asked her not to write again: "The sight of your letters I am obliged to confess turns me white with emotion and I have acute heart attacks following on from that."

In the edition published on 18th June 1912, Ada Nield Chew created further controversy with an article on the role of women in marriage. She argued that the emancipation of women depended on their gaining economic independence and rejecting the idea that their natural lifelong vocation was domestic and maternal. Ada, a working-class woman with children, added that: "A married woman dependent on her husband earns her living by her sex... Why, in the name of reason and common sense, should we condemn a mother to be a life-long parasite because she has had one or more babies to care for?"

In September 1912, The Freewoman was banned by W. H. Smith because "the nature of certain articles which have been appearing lately are such as to render the paper unsuitable to be exposed on the bookstalls for general sale." Dora Marsden argued that this was not the only reason the journal was banned: "The animosity we rouse is not roused on the subject of sex discussion. It is aroused on the question of capitalism. The opposition in the capitalist press only broke out when we began to make it clear that the way out of the sex problem was through the door of the economic problem."

Charles Grenville wrote to Dora Marsden complaining that the journal was losing about £20 a week and told her he was thinking of withdrawing as the publisher of the magazine. Marsden replied: "You have put money into the paper. I have put in the whole of my brain, power and personality. Without your money I would not have started, without my brain the paper could not have lived and shown the signs of flourishing which it undoubtedly has."

When Edward Carpenter realised the journal was being brought to an end, he wrote to Dora Marsden: "The Freewoman did so well during its short career under your editorship, it was so broad-minded and courageous that its cessation has been real loss to the cause of free and rational discussion of human problems."

The last edition of The Freewoman appeared on 10th October 1912. Dora told her readers: "The editorial work has not been easy. We have been hemmed in on every side by lack of funds. We have, moreover, been promoting a constructive creed, which had not only to be erected as we went along, we had also to deal with the controversy which this constructive creed left in its wake.... The entire campaign has been carried on indeed only at the cost of a total expenditure of energy, and we, therefore, do not hold it possible to continue the same amount of work, with diminished resources, if in addition, we have to bear the entire anxiety of securing such resources as are to be at our disposal."

Dora appealed to readers to help fund a new magazine. Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw both sent money. Lilian McErie also contributed: "No paper has given me keener pleasure than yours. Its fearlessness and fairness made all lovers and seekers after truth respect it and love it even while differing from many of the opinions expressed therein."

In February 1913 Dora met Harriet Shaw Weaver, who had just inherited a large sum of money from her father. As Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit, pointed out: "They were in many ways totally unsuited - on the one hand, the rebellious, radical intellectual and on the other, the quiet, modest, unassuming and orderly Weaver. Yet they took an immediate liking towards each other - Weaver impressed by Dora's intelligence and indeed, her beauty, and Dora by Harriet's keen but systematic approach to the re-launch of the paper. Dora had originally just wanted a chat but they ended up in effect having a business meeting while all the time establishing their mutual respect and admiration".

The New Freewoman was launched in June 1913. The journal, published fortnightly, was priced at 6d but readers were asked to pay £1 in advance for 18 months' copies. Dora Marsden wrote in the first edition: "The New Freewoman is not for the advancement of Women, but for the empowering of individuals - men and women.... Editorially, it will endeavour to lay bare the individual basis of all that is most significant in modern movements including feminism. It will continue The Freewoman's policy of ignoring in its discussion all existing taboos in the realms of morality and religion."

Harriet Shaw Weaver put up £200 to fund the magazine and this gave her a controlling interest in the venture. Dora Marsden was editor, Rebecca West assistant editor and Grace Jardine (sub-editor and editorial secretary). The women were all employed on a salary of £1 a week. Later, Ezra Pound, became the journal's literary editor.

H. G. Wells welcomed the new magazine: "I rejoice beyond all measure in the revival of The Freewoman. Its policy even at its worse was a wholesome weekly irritant." Benjamin Tucker said "I consider your paper the most important publication in existence." Winifred Leisenring, the secretary of the Blavatsky Institute, argued that the journal "will educate women and men to think in terms of true freedom, and show them that real individuality exists apart from all our accepted standards."

Elizabeth Crawford pointed out that "Marsden... continued her attack on the Pankhursts, using the death of Emily Wilding Davison to highlight her conviction that they were prepared to make use of dedicated individuals, who otherwise were considered as trouble-makers, only when it suited them." Marsden wrote on 15th June, 1913: "Davison's death was merely to give a crowd of degenerate orgiastics a new sensation... Causes are the diversion of the feeble - of those who have lost the power of acting strongly from their own nature."

Dora Marsden and Harriet Shaw Weaver became very close. Dora wrote to Harriet claiming that "you have been a perfect treasure to me and the paper". Harriet wrote back expressing her love for Dora. Rebecca West also enjoyed working under Dora, telling her that she was a "wonderful person, you not only write these wonderful first pagers but you inspire other people to write wonderfully."

The New Freewoman gradually moved away from its feminist origins. George Lansbury complained about Marsden's abandonment of socialism and others disliked the emphasis she placed on individualism. Her critics included Rebecca West who resigned her post in October 1913 having become disillusioned with the direction the journal was taking. Later she admitted she strongly disapproved of Dora's "aggressive individualism" and her "egotistic philosophy". Dora replaced Rebecca with the young poet, Richard Aldington.

At a director's meeting on 25th November 1913, it was decided to change the name of the The New Freewoman to The Egoist: An Individualist Review. Bessie Heyes complained to Harriet Shaw Weaver about the change of name. "Don't you yourself think that the paper is not accomplishing what we intend to do? I had such hopes of The New Freewoman and it seems utterly changed." The journal lasted for only seven months and thirteen issues. During this time it only obtained 400 or so regular readers.

In 1913 Christabel Pankhurst published The Great Scourge and How to End It. She argued that most men had venereal disease and that the prime reason for opposition to women's suffrage came from men concerned that enfranchised women would stop their promiscuity. Until they had the vote, she suggested that women should be wary of any sexual contact with men. Marsden criticised Pankhurst for upholding the values of chastity, marriage and monogamy. She also pointed out in The Egoist on 2nd February 1914 that Pankhurst's statistics on venereal disease were so exaggerated that they made nonsense of her argument. Marsden concluded the article with the claim: "If Miss Pankhurst desires to exploit human boredom and the ravages of dirt she will require to call in the aid of a more subtle intelligence than she herself appears to possess." Other contributors to the journal joined in the attack on Pankhurst. The Canadian feminist, R. B. Kerr argued that "her obvious ignorance of life is a great handicap to Miss Pankhurst" (16th March, 1914) whereas Ezra Pound suggested that she "has as much intellect as a guinea pig" (1st July, 1914).

Marsden continued to criticise the Women Social & Political Union. On 15th June, 1914, attacked Emmeline Pankhurst for being under the control of a small group of rich women: "Mrs Pankhurst required at the outset, for the sake of backing, women with money and with some capacity: when she obtained these she drew the limiting line which would keep out women with accepted followings and too much ability: that is unless they came with ashes in their hair, repentance in one hand and passivity in the other. Then on the principle of the Eastern potentate who illustrated the practice of good government by lopping off the heads of all the stalks of grain which grew higher than the rest, she by one means or another rid her group of all its members unlikely by virtue of personality, conspicuous ability, or undocile temper, to prove flexible material in the great cause. The gaps thus made she filled up with units of stock size."

Ezra Pound wanted the The Egoist to become more of a literary journal. In early 1914 he persuaded Dora Marsden to serialise A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, an experimental novel written by James Joyce. In the summer of 1914 Dora Marsden handed over the editorship of the The Egoist to Harriet Shaw Weaver. She now assumed the role of contributing editor. This allowed her to concentrate on her philosophical research and writings. However, both women were concerned by the poor sales figures of the journal. After briefly reaching 1,000 copies it had now fallen to a circulation figure of 750.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace." After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney, Margaret Ashton, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

Marsden refused to support these peace activists. She argued in a letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver: "The suffragist women of America and of such as Mrs. Swanwick, Margaret Ashton, Mrs. Philip Snowden here have: i.e. that conventions, treaties, words and documents are the bases of a community's existence rather than tempers, ambition, will and power. They don't realise that the conventions are only a superstructure erected on a stability which follows upon an apprehension of the relative powers represented by conflicting powers and wills: the apprehension itself being arrived at only after actual conflict has rendered it unmistakable."

In fact, Marsden gradually took the position of the WSPU. In the The Egoist: An Individualist Review on the 1st June, 1915, she argued the "delayers of peace are those who would temper down the ferocity which would wage war only at its deadliest". Marsden also supported conscription. In the journal she claimed that "everything which militates against the British Empire becoming a military camp until victory is assured is treason". Marsden believed that arming the male population would lead to revolution. She suggested that "men who have prepared themselves to defend their country will find themselves better equipped to defend themselves".

Her biographer, Les Garner, has pointed out: "Revolutionary Socialists might have sympathized with this but had a far more rigorous attitude to the war. Like Lenin, they saw the war largely as a battle between German and British capitalism for trade, markets and profit. The only benefit they envisaged was that by increasing economic and social crisis within the warring countries, class consciousness and thus the revolution would be hastened. Arming the workers as soldiers would help to this end. But this position envisaged the arming of a class not a hotch-potch of disparate individuals. It saw the war in economic terms and not merely as a clash of national interests, a sort of Egoism writ large. Dora's analysis clearly did not fit this position - or indeed any other. She was alienated from the liberal suffragist pacifist view and also from the jingos. Once again, she was on her own."

In January 1916, Harriet Shaw Weaver argued that despite poor sales she was determined to continue supporting the journal. "It has skirted all movements and caught on to none.... The Egoist is wedded to no belief from which it is willing to be divorced. To probe to the depths of human nature, to keep its curiosity in it fresh and alert, to regard nothing in human nature as foreign to it, but to hold itself ready to bring to the surface what may be found, without any pre-determination to fling back all but unwelcome facts - such are the high and uncommon pretensions upon which it bases its claims to provenance."

James Joyce failed to find a publisher for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Weaver agreed to establish the Egotist Press and the book was published in February 1917. The book was praised by critics such as H. G. Wells but was attacked by the mainstream press. The editor of The Sunday Express described it as "the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature."

In January 1919 The Egoist began the serialisation of Joyce's Ulysses. However, sales of the journal had fallen from 1,000 in May 1915 to 400 and Harriet Shaw Weaver, decided to bring the journal to an end. Dora Marsden now moved to the Lake District and established a home in Glenridding. At first she was very happy with her new life. She wrote to Harriet: "The really magic thing about the place is the atmosphere which makes everything indescribably seductively lovely. These last two weeks in October and the first ten days of November have been the most beautiful I have ever experienced. I shall never forget it. One has seemed to be living and working through a crystal globe flushed with every kind of soft but penetrating light. Spring was crude compared with it.... Will you join? Do think seriously about it. It is quite an addition to one's experience. I have never before experienced anything like it." According to Les Garner: "Apart from the frequent and crucial visits of Harriet Shaw Weaver, Dora's life was indeed isolated." Marsden, funded by Weaver, spent her time writing a proposed seven volume series on philosophy.

In 1928 Marsden sent the manuscript for The Definition of the Godhead to Harriet Shaw Weaver, the novelist, Margaret Storm Jameson and the philosopher, Samuel Alexander. Weaver was critical but Jameson believed it to be a very important work. Alexander replied that he was "astonished by the mass of knowledge you have acquired... yet I do not think you should try to publish it in its present form.

Marsden was unwilling to change the manuscript and Weaver agreed to resurrect the Egoist Press and it was finally published on 1st December 1928. Marsden wrote in the introduction: "This work is the first volume of a philosophy which claims to affect the intellectual rehabilitation of the dogmas of Christian theology in terms of the characters of the first principles of physics, i.e. Space and Time... (It is an attempt ) to solve the riddle of the first principles solutions are required to those age old problems of philosophy and theology which impart into human culture its heavily tangled undergrowth. This opening work, therefore, presents these solutions, unifying by means of them the whole body of human knowledge and re-interpreting all the great issues of mankind's cultural history.

Copies were sent to George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell and a large number of university professors. The book was also sent to journals and newspapers but it received only negative reviews. The Definition of the Godhead sold only six copies, one of these was to her friend, Rona Robinson. Weaver's accounts show an income of £4 9s. against total expenditure of £549 18s.

Her biographer, Les Garner, pointed out that her book was unpopular with those who had been involved in The Freewoman and The New Freewoman: "Dora's views on sex and the need for abstinence for those seeking the truth of the universe were, yet again, a thinly disguised justification of her own life since at least 1921." Harriet Shaw Weaver commented that: "It was a pity to make so much of sex. My view, for what it is worth, is the best way to treat sex is to forget it as far as possible."

The Mysteries of Christianity was published by the Egoist Press in 1930. After the poor sales of The Definition of the Godhead, Harriet only printed 500 copies and of these, only 100 were bound. Most of these were sent out to review but only one appeared, in The Times Literary Supplement. "Miss Marsden has ranged the whole world of folklore and myth to prove the familiar mysteries of the Christian faith are natural growths in the process of human evaluation. Her conclusions are at variance with most students of religion and anthropology, and very often she appears to accommodate her facts to her theories but those who are interested in myth and legend should find something to interest them if they are not bewildered too much by the constant use of curiously hyphenated words and phrases."

Soon after the book was published, Dora Marsden suffered a mental breakdown. Les Garner pointed out that by 1931 "Dora's physical and mental health was poor. Her moods fluctuated between delusive optimism about further volumes and a rational acceptance that her work was over." In 1932 Dora told Harriet that she planned to begin work on a third volume. "Harriet, who had abandoned any plans to back and publish Dora again, knew her friend's hopes were delusory."

On 26th November 1935 Marsden became a patient at the Crichton Royal Hospital in Dumfries. The hospital commented that she "was not able to communicate rationally, was severely depressed and was diagnosed as suffering from deep melancholia." The hospital later reported: "For the last twelve years she has lived the life of a recluse alone with her books and her studies. She felt she has found something of great importance in the world of thought - a criticism of philosophy from the earliest days onwards - this work did not create the impression she wanted and she became depressed. In summer 1934 the patient denied herself sufficient food, cut herself off from others and pulled down her blinds to prevent anyone seeing her.... Since the end of June 1935 she has become more and more depressed."

Dora Marsden remained in Crichton Royal Hospital for the rest of her life. Occasionally she talked about returning to her planned seven volume series of books on philosophy, but most of the time she "settled into her routine of sewing, reading and silence". The hospital fees were paid by Harriet Shaw Weaver. In 1955 she even arranged for some of her early unpublished writings to appear under the title of The Philosophy of Time. After its publication, Dora's brother-in-law, James Dyson wrote to Harriet stating that "nobody has had a better or more considerable friend and colleague than you have proved to be."

Dora Marsden died of a heart attack in the hospital on 13th December 1960.

On this day in 1912, detectives arrived at the WSPU headquarters to arrest Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence had disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored her objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

Both Emmeline and Frederick went on hunger strike and had to face the full rigours of forcible feeding twice a day for several days. He later recalled the experience in his memoirs, Fate Has Been Kind (1943): "The head doctor, a most sensitive man, was visibly distressed by what he had to do. It certainly was an unpleasant and painful process and a sufficient number of warders had to be called in to prevent my moving while a rubber tube was pushed up my nostril and down into my throat and liquid was poured through it into my stomach. Twice a day thereafter one of the doctors fed me in this way. I was not allowed to leave my cell in the hospital and for the most part I had to stay in bed. There was nothing to do but to read; and the days were very long and went very slowly."

Christabel Pankhurst later recorded: "Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed."

After Emmeline and Frederick were released from prison they began to speak openly about the possibility that this window-smashing campaign would lose support for the WSPU. At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline and Frederick about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) wrote: "Even the split with the WSPU did not end of this agony - the Pethick-Lawrences were still facing bankruptcy proceedings. An auction of their belongings was held at The Mascot, but raised only £300 towards their £1,100 court costs even though many friends arrived to buy personal possessions and give them back to the couple. Even the auctioneer returned to them a trinket he had bought as a keepsake. The rest of the costs were later taken from Fred's estate, plus a further £5,000 for repairs to shop windows damaged in the raids. Fortunately he had deep pockets and did not have to sell his home."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence continued to work for the suffrage cause and spent most of her energies after 1912 writing for her journal, Votes for Women. She also joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Other members included Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard.

During the First World War Emmeline was a prominent member of the Women's International League for Peace. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence stood as Labour candidate for Rusholme. As Brian Harrison pointed out: "she championing nationalization, a capital levy, equal pay, and an equal moral standard, but she came bottom of the poll with only a sixth of the votes cast."

In the 1920s and 1930s Emmeline worked for the Women's International League, an organisation committed to world peace. Emmeline also became involved in the campaign led by Marie Stopes to provide birth-control information to working class women. From 1926 to 1935 was president of the Women's Freedom League.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence published her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World, in 1938. The book is dedicated to her husband, "my unchanging comrade and my best friend". One critic argued: "Though impressively fair-minded and at times perceptive, her account of the suffragettes is essentially an uncritical and largely impersonal chronology. Nowhere did she convincingly justify the contradiction between her humanitarian and democratic instincts on the one hand, and her promotion of violent tactics and authoritarian suffrage structures on the other."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence remained active in politics until 1950 when she had a serious accident that left her immobilized. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence looked after Emmeline until she died of a heart attack at her home at Gomshall, Surrey, on 11th March 1954. He wrote to a friend: "I feel a bit dazed. It is as though I was at a violin concerto with the violinist absent."

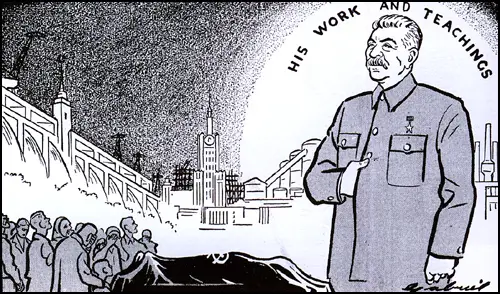

On this day in 1953 Joseph Stalin dies. After the Second World War Stalin's health began to deteriorate. His main problem was high blood-pressure. While he was ill, Stalin received a letter from a Dr. Lydia Timashuk claiming that a group of seven doctors, including his own physician, Dr. Vinogradov, were involved in a plot to murder Stalin and some of his close political associates. The doctors named in the letter were arrested and after being tortured, confessed to being involved in a plot arranged by the American and British intelligence organizations.

Stalin's response to this news was to order Lavrenti Beria, the head of the Secret Police, to instigate a new purge of the Communist Party. Members of the Politburo began to panic as they saw the possibility that like previous candidates for Stalin's position as the head of the Soviet Union, they would be executed.

Fortunately for them, Stalin's health declined even further and by the end of February, 1953, he fell into a coma. After four days, Stalin briefly gained consciousness. The leading members of the party were called for. While they watched him struggling for his life, he raised his left arm. His nurse, who was feeding him with a spoon at the time, took the view that he was pointing at a picture showing a small girl feeding a lamb. His daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, who was also at his bedside , later claimed that he appeared to be "bringing a curse on them all". Stalin then stopped breathing and although attempts were made to revive him, his doctors eventually accepted he was dead.

On this day in 1981 Yip Harburg died. Isidore Hochberg, the son of immigrants from Russia was born in New York on 8th April, 1898. He began writing poetry at high school but after graduating he found work as a meat-packer. In 1920, Hochberg, who had now changed his name to Edgar (Yip) Harburg, established himself as a successful electrical contractor. However his company went bankrupt following the Wall Street Crash and the arrival of the Depression.

Out of work, a friend from school, the songwriter, Ira Gershwin, introduced him to a musician, Jay Gorney. Together they wrote Brother Can You Spare a Dime (1932), a song about unemployment. Harburg moved to Hollywood where he wrote the lyrics for a series of musicals including Gold Diggers (1933), The Singing Kid (1936), The Wizard of Oz (1939), a film for which he won an Academy Award, Cabin in the Sky (1943), Can't Help Singing (1944), California (1946) and Centennial Summer (1946). These films included songs such as Only a Paper Moon, April in Paris, Over the Rainbow, Old Devil Moon and If This Isn't Love.