On this day on 26th March

On this day in 1633 Mary Beale was born. Mary Cradock, the daughter of a rector, was born in Barrow, Suffolk, on 26th March, 1633. When she was eighteen she married Charles Beale. After studying under Robert Walker, she became a portrait painter.

Mary Beale, who was influenced by the work of Peter Lely, became one of the most important portrait painters of the 17th Century. Her son, Charles Beale, also became a painter.

Mary Beale died in October 1699.

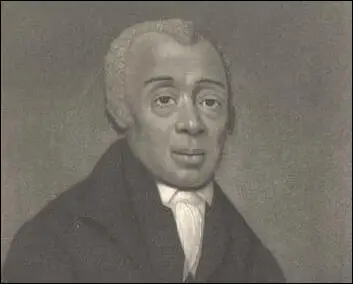

On this day in 1831 Richard Allen died. Richard Allen was born to slave parents in Philadelphia on 14th February, 1760. He was sold to a farmer in Delaware and in 1777 became a Methodist convert.

His master allowed him to preach in public and in 1786 he purchased his freedom and moved to Philadelphia where he conducted prayer meetings for blacks.

Dissatisfied with the restrictions placed on blacks who attended church services, in 1787 Allen helped organize an Independent Methodist Church. They converted an old blacksmith shop into America's first church for black people.

In 1816 Allen helped establish the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and he was elected as its first bishop. The following year Allen joined with James Forten to form the Convention of Color. The organization argued for the settlement of escaped black slaves in Canada but was strongly opposed to any plans for repatriation to Africa. Other leading figures that became involved in the movement was William Wells Brown, Samuel Eli Cornish and Henry Highland Garnet.

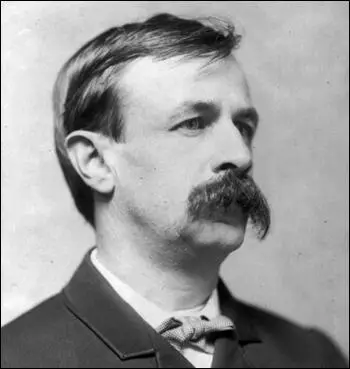

On this day in 1850 Edward Bellamy was born at Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. His father, Rufus King Bellamy, was a Baptist minister, whereas his mother, Maria Louisa Putnam Bellamy, was a Calvinist. Bellamy studied law but determined to be a writer, he began working for the newspaper, the Springfield Union. He later moved to the New York Post.

Bellamy also had several novels published including The Duke of Stockbridge (1879), Dr. Heidenhoff's Process (1880) and Miss Ludington's Sister (1884). Bellamy became a socialist after reading The Cooperative Commonwealth: An Exposition of Modern Socialism by Laurence Gronlund.

Looking Backward appeared in 1888. Set in Boston, the book's hero, Julian West, falls into a hypnotic sleep and wakes in the year 2000, to find he is living in a socialist utopia where people co-operate rather than compete. Edward W. Younkins has argued: "This novel of social reform was published in 1888, a time when Americans were frightened by working class violence and disgusted by the conspicuous consumption of the privileged minority. Bitter strikes occurred as labor unions were just beginning to appear and large trusts dominated the nation’s economy. The author thus employs projections of the year 2000 to put 1887 society under scrutiny. Bellamy presents Americans with portraits of a desirable future and of their present day. He defines his perfect society as the antithesis of his current society. Looking Backward embodies his suspicion of free markets and his admiration for centralized planning and deliberate design."

The novel was highly successful and sold over 1,000,000 copies. It was the third largest bestseller of its time, after Uncle Tom's Cabin and Ben-Hur. As his biographer, Franklin Rosemont, has pointed out: "The social transformation described in Looking Backward has in turn transformed, or rather liberated, the human personality. In Bellamy's vision of the year 2000, selfishness, greed, malice, insanity, hypocrisy, lying, apathy, the lust for power, the struggle for existence, and anxiety as to basic human needs are all things of the past."

Bellamy Clubs were established all over the United States for discussing and propagating the book's ideas. His ideas were also well received in Europe. Alfred Salter, a member of the Labour Party in Britain, read the book as a young man and along with his wife, Ada Salter, attempted to build Bellamy's utopia in Bermondsey.

Bellamy's book also inspired the Garden City movement. As Stanley Buder, the author of Visionaries and Planners: The Garden City Movement and the Modern Community (1991), has pointed out: "Bellamy also envisioned an environmental setting suitable for his new social order. His Boston of the year 2000 is a small city of parklike appearance. Neat, unostentatious homes filled with conveniences face broad treelined boulevards. Conveniently located public laundries and central dining halls relieve the drudgery of housework and end the isolation of domestic life. Dominating the city are handsome and commodious public buildings of classical architecture and gleeming whiteness which provide the center of community life. Needless to say, slums, saloons, and the excitement of crowds or the enticement of loitering before shop windows have been eliminated. An efficient, ordered life is what Bellamy's future promised. The author ingeniously combined state control in matters of production and distribution with private initiative in the arts to project what he regarded as a truly satisfying and liberal society."

According to Benjamin Flower: "Edward Bellamy possessed a charming and lovable personality. There was nothing of the militant reformer about him, although he was a man who held steadfastly to his convictions." Erich Fromm has argued that the is "one of the most remarkable books ever published in America." People who have claimed that they were deeply influenced by the book include, Heywood Broun, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Daniel De Leon, Eugene Debs, Julius Wayland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Upton Sinclair, Scott Nearing and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

A strong supporter of the nationalization of public services, Bellamy's ideas encouraged the foundation of what became known as Nationalist Clubs. He also became editor of The Nationalist (1889-91) and the New Nation (1891-94).

Bellamy's Equality (1897) was an attempt to answer the critics of Looking Backward. The book emphasised the central role of women in radical social change. It also provided a bold affirmation of animal rights and wilderness conservation. Peter Kropotkin argued that he knew of "no other socialist work... that equals Bellamy's Equality."

Edward Bellamy died from tuberculosis at Chicopee on 22nd May, 1898.

On this day in 1854 Harry Furniss, the son of an English engineer, was born in County Wexford, Ireland. His mother was the miniaturist painter Isabella Mackenzie. After leaving school he worked as a clerk to a wood-engraver, who taught him the trade.

Furniss worked as an artist in Ireland but in 1876 he moved to England and found work with the Illustrated London News. Over the next eight years he developed a reputation as an outstanding draughtsman. He also contributed to The Pall Mall Gazette, The Daily News, The Sketch, Vanity Fair, The Graphic, and The Windsor Magazine.

In October 1880, Francis Burnand, the editor of Punch Magazine, invited Furniss to contribute to the magazine. Several of his cartoons were published and in 1884 he became a member of the staff at the magazine. For the next ten years he illustrated the "Essence of Parliament". He also supplied articles, jokes, illustrations and dramatic criticisms for other sections of the magazine. It is estimated that over the years he contributed more than 2600 drawings to the magazine.

Harry Furniss always drew William Gladstone with a large collar, and although he never wore collars like this, the public become convinced that he did. Furniss was a staunch Unionist and he was especially harsh on Irish Nationalists. One MP, Swift MacNeill, who was portrayed as a gorilla, was so angry with that he physically assaulted Furniss. Another group of MPs threatened him with a beating unless he ended his campaign against them.

Harry Furniss work became extremely popular with the British public and this enabled him to tour the country giving lectures on subjects such as "The Frightfulness of Humour" and "Humours of Parliament". Furniss also illustrated a great number of books including those by Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Mark Bryant has pointed out: "He rarely used an easel but preferred to work standing up at a waist-high desk. He drew in pen and ink but also worked in chalk and painted in watercolours and oils." R.G.G. Price, the author of A History of Punch (1957) has argued that Furniss was "not a great draughtsman... but a very experienced pictorial journalist who could work fast and get a likeness easily. It is said that he would chat to a man and caricature him on a pad held in his pocket".

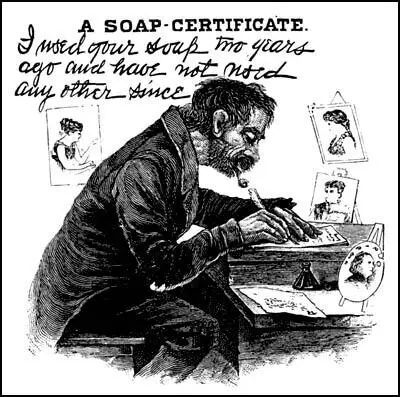

Harry Furniss left Punch Magazine in 1894 after a discovered that the magazine had sold the copyright of one of his drawings to Pears Soap for advertising. Furniss had for a long time wanted his own business and that year he started his own cartoon magazine, Like Joka. It sold 140,000 copies on its first day.

However, the magazine was not a long-term financial success and he moved to the USA where he worked in the film industry with Thomas Edison. Furniss helped pioneer the animated cartoon films with Peace and War Pencillings (1914).

Harry Furniss died at his home in Hastings on 14th January, 1925.

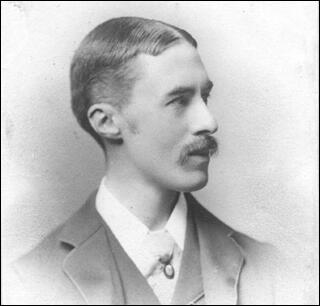

On this day in 1859 poet Alfred Edward Housman was born in Frockbury, Worcestershire. Educated at Bromsgrove School, he won a scholarship to St. John's College, Oxford. He became a distinguished classical scholar and in 1892 was appointed professor of Latin at University College, London.

In 1896 he published A Shropshire Lad. The 63 poems recall the innocence, the pleasures and the tragedies of the countryside. He also published critical editions of Manilius (1903) and Juvenal (1905). In 1911 Housman became Professor of Latin at Cambridge University. His brother, Laurence Housman, was also a successful writer and illustrator.

During the First World War Housman published several poems about the conflict including Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries (1914).

Housman continued to write poetry and his Last Poems (1922) met with great acclaim. Praefanda (1931) was a collection of bawdy and obscene passages from Latin authors.

Alfred Edward Housman died on 30th April 1936.

On this day in 1876 Kate Richards was born. Kate Richards was born in Ada, Kansas, on 26th March, 1877. After a brief schooling in Nebraska, she became an apprentice machinist in Kansas City. Deeply religious, Richards joined the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

Richards was influenced by the books on overcoming poverty by Henry George and Henry Demarest Lloyd. However, it was a speech made by Mary 'Mother' Jones and meeting Julius Wayland, the editor of Appeal to Reason, that converted her to socialism.

Richards joined the Socialist Labor Party in 1899 and two years later the Socialist Party of America. In 1902 she married Francis O'Hare and they spent their honeymoon lecturing on socialism. This included visits to Britain, Canada and Mexico. Richards wrote the successful socialist novel, What Happened to Dan? (1904) and with her husband edited the National Rip-Saw, a radical journal published in St. Louis. In 1910 she unsuccessfully ran for the Kansas Congress.

Richards believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and argued that the USA should remain neutral. In 1917 Richards became chair of the Committee on War and Militarism and toured the country making speeches against the war.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the government passed the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to make speeches that undermined the war effort. Criticised as unconstitutional, the act resulted in the imprisonment of many members of the anti-war movement including 450 conscientious objectors.

In July, 1917, Richards was sentenced to five years for making an anti-war speech in North Dakota. The judge told her: "This is a nation of free speech; but this is a time for sacrifice, when mothers are sacrificing their sons. Is it too much to ask that for the time being men shall suppress any desire which they may have to utter words which may tend to weaken the spirit, or destroy the faith or confidence of the people?"

While in prison Richards published two books, Kate O'Hare's Prison Letters (1919) and In Prison (1920). After a nationwide campaign President Calvin Coolidge commuted her sentence. In 1922 Richards organized the Children's Crusade, a march on Washington, by children of those anti-war agitators still in prison.

Richards and her husband settled in Leesville, Louisiana, where they joined the Llano Cooperative Colony, published the American Vanguard and helped establish the Commonwealth College. Richards also took a keen interest in prison reform and carried out a national survey of prison labour (1924-26).

In 1928 Richards married Charles Cunningham, a San Francisco lawyer. She remained active in politics and in 1934 helped Upton Sinclair in his socialist campaign to become the governor of California.

Kate Richards, who was assistant director of the California Department of Penology (1939-40) died in Benicia, California, on 10th January, 1948.

she kept with her after being imprisoned in 1917

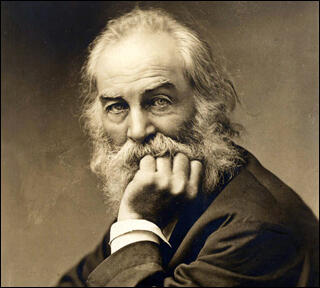

On this day in 1892 Walt Whitman died. Whitman, one of nine children, was born in West Hills, Long Island on 31st May, 1819. The family moved to Brooklyn in 1823 where his father found work as a carpenter.

Whitman left school at twelve and began work as a printer. He continued his studies and eventually became a teacher on Long Island and edited the local newspaper, the Long Islander.

In 1841 Whitman moved to New York. and worked for several newspapers including the editorship of New York Aurora and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. A member of the Free-Soil Party, Whitman was a strong opponent of slavery and in 1848 his radical political views resulted in him being sacked as editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

After making several attempts at radical journalism, Whitman moved into the real estate business and made a living building and selling houses. Whitman continued to write and in 1855 he privately published a book of twelve poems entitled, Leaves of Grass. In the introduction to the book Whitman proclaimed himself the symbolic representative of common people. The sexual content of the poems resulted in some critics declaring it to be an immoral book. The book sold badly and unable to become a full-time poet, Whitman returned to journalism, working as editor of the Brooklyn Times (1856-1859).

A new edition of Leaves of Grass, which contained 124 new poems, appeared in 1860. Ralph Waldo Emerson praised the book but it was ignored by most critics at the time. However, Whitman's use of colloquial language and everyday events, represented a turning-point in the history of American poetry.

Whitman was a Radical Republican and was therefore a strong supporter of the Union Army during the American Civil War. His brother was wounded at Fredericksburg, and Whitman went there to visit him in hospital. When he returned to Washington he spent his spare time visiting soldiers at Armory Square Hospital. He also reported on the conflict for the New York Times. He also published two collections of war poems Drum Taps (1865) and Sequel to Drum Taps (1866). This included several poems in praise of Abraham Lincoln.

After the war Whitman worked as a clerk in the Department of the Interior in Washington but was dismissed when it was discovered he was the author of Leaves of Grass. The Secretary of the Interior, like many people at the time, considered it to be an indecent book. Whitman worked in a series of menial jobs and continued to write with Democratic Vistas appearing in 1871.

In 1873 Whitman suffered a paralytic stroke and for the next twenty years lived in a semi-invalid state. Whitman now left Washington for Camden, New Jersey where he spent the remainder of his life. A new edition of Leaves of Grass, now containing 293 poems, was published in 1881. He also published a collection of prose writings, Specimen Days (1881) and newspaper pieces, November Boughs (1888).

Walt Whitman died in on 26th March, 1892.

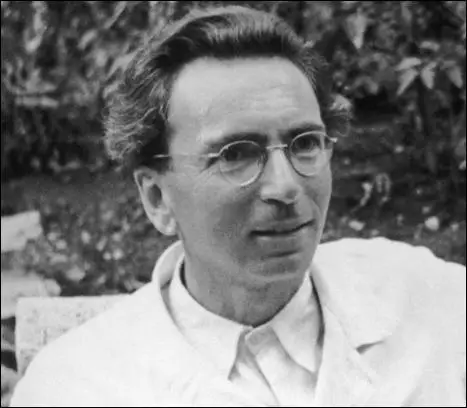

On this day in 1905 psychiatrist Viktor Frankl was born in Vienna into a Jewish family. His father held a government job administering children's aid. His mother was described as a "kindhearted and deeply pious woman." His father tended to be hot-tempered. "In a fit of anger he once broke an alpine walking stick as he hit me with it. Despite this, to me he was always the personification of justice. And he always provided us with a sense of security."

As a teenager he did brilliantly in his studies, which included a course in psychology that prompted him at the age of 16 to write to Sigmund Freud. A correspondence ensued, and in one letter he included a two-page paper he had written. Freud loved it, sent it promptly to the editor of his International Journal of Psychoanalysis and wrote the boy, '"I hope you don't object.'"

Victor Frankl became a socialist and joined the Social Democratic Party of Austria and in 1924 he became the president of its youth organization. Later that year he entered the University of Vienna to study medicine and over this period he specialized in neurology and psychiatry, concentrating on the topics of depression and suicide. His early development was influenced by the work of Alfred Adler. However, later he began to feel that Adler erred in denying that people had the freedom of choice and willpower to overcome their problems.

In the summer of 1927, three members of an Austrian right-wing paramilitary group accused of murdering an eight-year-old boy and elderly war veteran were acquitted by a conservative judge. In Vienna there were strikes and riots in protest. The police were ordered to shoot directly into the crowd and as a result 89 people died and hundreds were wounded. Frankl who was one of those who treated the injured, was radicalized by these events. When Wilhelm Reich asked Sigmund Freud for his opinion on the "civil war", his mentor replied that he was fundamentally unsympathetic to the "primal horde".

Between 1928 and 1930, while still a medical student, he organized and offered a special program to counsel high school students free of charge. The program involved the participation of psychologists such as Charlotte Bühler, and it paid special attention to students at the time when they received their report cards. It was reported that in 1931, not a single Viennese student committed suicide.

Reich began associating with left-leaning therapists such as Karen Horney, Ernst Simmel, Erich Fromm, Wilhelm Reich, Edith Jacobson, Helene Deutsch, Frieda Reichmann, Edith Weigert and Otto Fenichel who began to take into consideration the social and political impact on the clinical situation. Together they explored ways of "finding a bridge between Marx and Freud". Elizabeth Ann Danto, described the group as being interested in providing "a challenge to conventional political codes, a social mission more than a medical discipline."

In 1937, Frankl established his own private practice in neurology and psychiatry at Alser Strasse in Vienna. He also acted out his socialist beliefs and "did most of my work for no money at all, in clinics for the poor." After the invasion of Austria by the German Army in 1938, Frankl was thereby prohibited from treating "Aryan" patients due to his Jewish identity and due to the Anschluss from owning and operating his prior business/practice.

In 1940, becomes director of the Neurological Department of the Rothschild Hospital, a clinic for Jewish patients. This hospital was the only one in Vienna to which Jews were still admitted. In spite of the danger to his own life he sabotages Nazi procedures by making false diagnoses to prevent the euthanasia of mentally ill patients. Frankl obtained an immigration visa to America but did not use it because he does not want to desert his old parents. In 1941 Frankl married Tilly Grosser.

The next month his entire family, except for a sister who had left the country, was arrested in a general roundup of Jews. The family had expected the roundup, as his wife, Tilly Frankl, sewed the manuscript of the book he was writing on his developing theories of psychotherapy into the lining of his coat. After their arrival at Auschwitz, Frankl was separated from his family. His own clothes were replaced with prison clothes, and the manuscript was lost. Frankl's father died there of starvation and pneumonia. His mother and brother were gassed. His wife died later of typhus in Bergen-Belsen.

Concentration camps were controlled by the Schutzstaffel (SS), but day-to-day organization was supplemented by the system of prisoners, Kapos, a second hierarchy that made it easier for the Nazis to control the camps. These prisoners made it possible for the camps to function with the minimum number of German soldiers, who were needed to fight on the front-line. The Kapos often did this work for extra food, cigarettes, alcohol or other privileges as well as being protected from being executed.

It has been pointed out: "The perfidy of the Nazi regime was in forcing the Jewish victims to be instruments of their own destruction. Jews were at the bottom of the hierarchy in the Nazi concentration camps, with the lowest food rations and selected for the most brutal labour. Jewish kapos were just one rung above the miserable existence of the ordinary Jewish prisoners... and increased a Jewish kapo's likelihood of survival tenfold." According to Lisa Yavnai becoming a Jewish kapo often meant choosing between the possibility of life and almost certain death.

Viktor Frankl suffered from cruel Kapos: "While these ordinary prisoners had little or nothing to eat, the Kapos were never hungry; in fact many of the Kapos fared better in the camp than they had in their entire lives. Often they were harder on the prisoners than were the guards, and beat them more cruelly than the SS men did. These Kapos, of course, were chosen only from those prisoners whose characters promised to make them suitable for such procedures, and if they did not comply with what was expected of them, they were immediately demoted. They soon became much like the SS men and the camp wardens and may be judged on a similar psychological basis."

Frankl described on one occasion why he was badly beaten by a Kapo: "Then he began: 'You pig, I have been watching you the whole time! I teach you to work, yet! Wait till you dig dirt with your teeth - you'll die like an animal! In two days I'll finish you off! You've never done a stroke of work in your life. What were you swine? A businessman?'. I was past caring. But I had to take his threat of killing me seriously, so I straightened up and looked him directly in the eye. 'I was a doctor - a specialist.' 'What? A doctor? I bet you got a lot of money out of people.' 'As it happens, I did most of my work for no money at all, in clinics for the poor.' But, now, I had said too much. He threw himself on me and knocked me down, shouting like a madman. I can no longer remember what he shouted."

However, Frankl was able to use his skills as a psychologist to gain the support of a senior Kapo: "Fortunately the Kapo in my working party was obligated to me; he had taken a liking to me because I listened to his love stories and matrimonial troubles, which he poured out during the long marches to our work site. I had made an impression on him with my diagnosis of his character and with my psychotherapeutic advice. After that he was grateful, and this had already been of value to me.... As long as my Kapo felt the need of pouring out his heart, this could not happen to me (being taken away to be executed). I had a guaranteed place of honour next to him... As an additional payment for my services, I could be sure that as long as soup was being dealt out at lunchtime at our work site, he would, when my turn came, dip the ladle right to the bottom of the vat and fish out a few peas."

His academic education also helped him survive: "In spite of all the enforced physical and mental primitiveness of the life in a concentration camp, it was possible for spiritual life to deepen. Sensitive people who were used to a rich intellectual life may have suffered much pain (they were often of a delicate constitution), but the damage to their inner selves was less. They were able to retreat from their terrible surroundings to a life of inner riches and spiritual freedom. Only in this way can one explain the apparent paradox that some prisoners of a less hardy make-up often seemed to survive camp life better than did those of a robust nature."

Frankl also pointed out: "Humour was another of the soul's weapons in the fight for self-preservation. It is well known that humour, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds. I practically trained a friend of mine who worked next to me on the building site to develop a sense of humour. I suggested to him that we would promise each other to invent at least one amusing story daily, about some incident that could happen one day after liberation."

In December 1944 Frankel had the opportunity to escape: "As the battle-front drew nearer, I had the opportunity to escape. A colleague of mine who had to visit huts outside the camp in the course of his medical duties wanted to escape and take me with him... Outside the camp, a member of a foreign resistance movement was to supply us with uniforms and documents... I made a quick last round of my patients, who were lying huddled on the rotten planks of wood on either side of the huts. I came to my only countryman, who was almost dying, and whose life it had been my ambition to save in spite of his condition. I had to keep my intention to escape to myself, but my comrade seemed to guess that something was wrong (perhaps I showed a little nervousness). In a tired voice he asked me, 'You, too, are getting out?' I denied it, but I found it difficult to avoid his sad look. After my round I returned to him. Again a hopeless look greeted me and somehow I felt it to be an accusation. The unpleasant feeling that had gripped me as soon as I had told my friend I would escape with him became more intense. Suddenly I decided to take fate into my own hands for once. I ran out of the hut and told my friend that I could not go with him. As soon as I had told him with finality that I had made up my mind to stay with my patients, the unhappy feeling left me. I did not know what the following days would bring, but I had gained an inward peace that I had never experienced before."

Auschwitz was liberated on 27th January, 1945: "Psychologically, what was happening to the liberated prisoners could be called 'depersonalization'. Everything appeared unreal, unlikely, as in a dream. We could not believe it was true. How often in the past years had we been deceived by dreams! We dreamt that the day of liberation had come, that we had been set free, had returned home, greeted our friends, embraced our wives, sat down at the table and started to tell of all the things we had gone through - even of how we had often seen the day of liberation in our dreams."

Viktor Frankl died on 2nd September, 1997

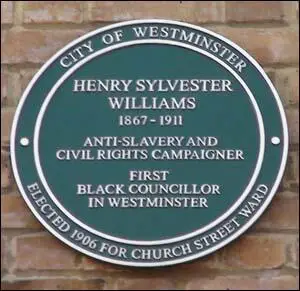

On this day in 1911 Sylvester Williams died. Williams, one of five children, was born in Trinidad. His father was a wheelwright who had originally come from Barbados. A talented student he qualified as a school teacher in 1886. He took a keen interest in politics and in January 1890 helped establish the Trinidad Elementary Teachers Union.

In 1891 Williams moved to New York where he worked as a public shoe-cleaner. Later he studied law at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia but left before graduating. In 1896 he travelled to England and entered King's College. To help far for his education Williams he lectured for the Church of England Temperance Society and the National Thrift Society. While in London Williams met and married Agnes Powell, a member of the Temperance Society. Her father, Captain Francis Powell, objected to the wedding and refused to meet Williams. Over the next few years the couple had five children.

Williams became increasingly interested in politics and in 1897 established the African Association. The following year he issued a statement calling for a conference "in order to take steps to influence public opinion on existing proceedings and conditions affecting the welfare of the natives in the various parts of the Empire, viz., South Africa, West Africa and the British West Indies". After a meeting with Booker T. Washington Williams decided to increase the scope of the conference by also looking at "the treatment of native races under European and American rule".

The Pan-African Conference was held at Westminster Town Hall in July 1900. There were 37 delegates from Europe, Africa and the United States. Those attending included Samuel Coleridge Taylor, John Alcindor, Dadabhai Naoroji, John Archer and William Du Bois. At the conference a large number of delegates made speeches where they called for governments to introduce legislation that would ensure racially equality. Michael Creighton, the Bishop of London, asked the British government to confer the "benefits of self-government" on "other races as soon as possible".

Some of the papers delivered at the conference included: The Trials and Tribulations of the Coloured Race in America (Bishop Alexander Walters), Conditions Favouring a High Standard of African Humanity (C. W. French), The Preservation of Racial Equality (Anna Jones), The Necessary Concord to be Established between Native Races and European Colonists (Benito Sylvain), The Negro Problem in America (Anna Cooper), The Progress of our People (John Quinlan) and Africa, the Sphinx of History (D. E. Tobias).

After the conference the Pan-African Congress wrote to Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary, suggesting that black people in the British Empire should be granted "true civil and political rights". Chamberlain replied that black people were "totally unfit for representative institutions". Williams responded to this by writing to Queen Victoria about the system "whereby black men, women, and children were placed in legalized bondage to white colonists". The letter was passed to Chamberlain who replied that the government would not "overlook the interests and welfare of the native races."

In 1901 Williams travelled the world and managed to set-up branches of the Pan-African Congress in the United States, Jamaica and Trinidad. In October, 1901, Williams established the journal The Pan African. He explained in the first edition that the main objective of the journal was to support the "interests of the African and his descendants in the British Empire". Williams added that in his opinion "that no other but a Negro can represent the Negro".

Membership of the Pan-African Congress remained small. Williams admitted that in 1901 it only had 50 working members. There were also 150 white sympathizers who were admitted to the organization as honorary members.

Williams was called to the bar in June 1902 and therefore became the first barrister of African descent to practise in Britain. Over the next few years he spent a lot of time defending black people involved in the campaign against racial prejudice in South Africa. He also spent time in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

Williams joined the Fabian Society and in November 1906 he and John Archer became the first people of African descent to be elected to public office in Britain. Williams won a seat on Marylebone Borough Council whereas Archer won in Battersea.

In 1908 Williams decided to return to Trinidad with his family and soon built a successful legal practice in Port of Spain. He continued to work as a lawyer until his death on 26th March, 1911.

On this day in 1966 Joel Rogers died. He was born in Negril, Jamaica in about 1880. He moved to the United States in 1906 and found work as a train porter in Chicago.

Rogers moved to New York City and along with Chandler Owen, Philip Randolph, E. Franklin Frazier, Joel Rogers, Hubert Harrison, George Schuyler, Roy Wilkins, Claude McKay, Scott Nearing, Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson and Eugene O'Neill, began contributing to The Messenger.

Rogers also contributed to Crisis and The Amsterdam News. Rogers later worked for the Pittsburgh Courier. This included reporting the Ethiopian-Italian war in 1935. He wrote several books on African American civil rights including Superman to Man (1941), Sex and Race (1944) and Great Men of Color (1975).

On this day in 1983 Anthony Blunt died of a heart attack at his home, 45 Portsea Hall, Westminster, London. Blunt, the third and youngest son of the Revd Stanley Vaughan Blunt (1870–1929) and his wife, Hilda Master (1880–1969), was born at Holy Trinity vicarage, Bournemouth, Hampshire, on 26th September 1907. As a child he spent time in Paris, where his father was the British embassy chaplain.

Blunt was educated at Marlborough School where he developed a strong interest in art. According to his biographer, Michael Kitson: "Blunt was part of a group of rebellious young aesthetes), he was producing precociously fluent defences of modern art, much to the infuriation of the deeply conservative art teacher - an early indication of his academic talent and his instinctive contrariness."

Blunt's best friend, Louis MacNeice, claimed that he suffered a great deal from bullying because he was an individualist and non-conformer: "Boys of that age are especially sadistic... They would seize him, tear off most of his clothes and cover him with house paint, then put him in the basket and push him round and round the hall... Government of the mob, by the mob, and for the mob... a perfect exhibition of mass sadism."

In 1926 Blunt won a scholarship to Trinity College. He arrived at Cambridge University during the General Strike. Like many students he felt sympathy for the miners. Maurice Dobb was a major influence on Blunt. A lecturer in economics, he had joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1922, and was open with his students about his communist beliefs. Dobb's friend, Eric Hobsbawm, has pointed out: "He (Dobb) joined the small band of Cambridge socialists as soon as he went up and... the Communist Party. Neither body was then used to such notably well-dressed recruits of such impeccably bourgeois comportment. He remained quietly loyal to his cause and party for the remainder of his life, pursuing a course, at times rather lonely, as a communist academic." Blunt admitted that "Cambridge had literally been transformed overnight by the wave of Marxism... the undergraduates and graduate students were swept away by Marxism" and that "during the next three of four years almost every intelligent undergraduate who came up to Cambridge joined the Communist party some time during his first year."

Blunt later claimed the two most important Marxists he came into contact with at university were John Cornford and James Klugmann. Blunt described Klugmann as "an extremely good political theorist" who "ran the administration of the Party with great skill and energy and it was primarily he who decided what organizations and societies in Cambridge were worth penetrating." John Costello has argued that this suggests that Blunt was already a member of the communist underground cell: "How did Blunt know this if he was not deeply implicated in the cell? Blunt's statement reveals a familiarity with the inside workings of the Cambridge Communist party that is significant. To know how decisions were taken about penetration suggests that he and Klugmann must have been on very close terms."

Blunt also joined the Cambridge Apostles. Other members over the years had included Guy Burgess, Michael Straight, Alister Watson, Julian Bell, Leo Long and Peter Ashby. It has been pointed out by Michael Kitson that the values of the group included the cult of the intellect for its own sake, belief in freedom of thought and expression irrespective of the conclusions to which this freedom might lead, and the denial of all moral restraints other than loyalty to friends. "An influential minority of the society's members were, moreover, like Blunt himself, homosexual at a time when homosexual acts were still illegal in Britain."

According to John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988), Blunt became very close to Guy Burgess: "Blunt was intensely fond of Burgess, and his personal loyalty never wavered... Burgess and Blunt did not share a lifelong sexual passion for each other, according to other bedmates... Such evidence as there is confirms that their intimacy quickly outgrew the bedroom. This was in keeping with the character of Burgess and his insatiable sexual appetite... Burgess had a peculiar talent for transforming his former lovers into close friends. To many of them, including Blunt, he became both father confessor and pimp who could be relied on to procure partners. Burgess devoured sex as he did alcohol - an over-indulgence that suggests he was drowning a deep sense of sexual inadequacy."

Anthony Blunt impressed his fellow students by his intellectual abilities. Victor Rothschild commented: "Like many others I was impressed by his outstanding intellectual abilities, both artistic and mathematical, and by what for want of a better word, I must call his high moral or ethical principles." In 1932 he was elected a fellow of Trinity College on the strength of a dissertation on artistic theory in Italy and France during the Renaissance and seventeenth century. Blunt also wrote on art for the Cambridge Review.

In 1933 he became the art critic of The Spectator. He caused great controversy when he took a Marxist approach to criticise the annual summer show at the Royal Academy: "I found almost as little skill as soul". He showed contempt for modern painters who portrayed "the pleasures of contemporary bourgeois life in a technique which aims, I imagine, principally at a tone of simple badinage." He condemned the institution of only "satisfying the demands of a particular class."

In January 1934 Arnold Deutsch, one of NKVD's agents, was sent to London. As a cover for his spying activities he did post-graduate work at London University. In May he made contact with Litzi Friedmann and Edith Tudor Hart. They discussed the recruitment of Soviet spies. Litzi suggested her husband, Kim Philby. "According to her report on Philby's file, through her own contacts with the Austrian underground Tudor Hart ran a swift check and, when this proved positive, Deutsch immediately recommended... that he pre-empt the standard operating procedure by authorizing a preliminary personal sounding out of Philby."

Kim Philby later recalled that in June 1934. "Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a 'man of decisive importance'. I questioned her about it but she would give me no details. The rendezvous took place in Regents Park. The man described himself as Otto. I discovered much later from a photograph in MI5 files that the name he went by was Arnold Deutsch. I think that he was of Czech origin; about 5ft 7in, stout, with blue eyes and light curly hair. Though a convinced Communist, he had a strong humanistic streak. He hated London, adored Paris, and spoke of it with deeply loving affection. He was a man of considerable cultural background."

Deutsch asked Philby if he was willing to spy for the Soviet Union: "Otto spoke at great length, arguing that a person with my family background and possibilities could do far more for Communism than the run-of-the-mill Party member or sympathiser... I accepted. His first instructions were that both Lizzy and I should break off as quickly as possible all personal contact with our Communist friends." It is claimed by Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) that Philby became the first of "the ablest group of British agents ever recruited by a foreign intelligence service."

Arnold Deutsch asked Kim Philby to make a list of potential recruits. The first person he approached was his friend, Donald Maclean, who had been a fellow member of the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS) and now working in the Foreign Office. Philby invited him to dinner, and hinted that there was important clandestine work to be done on behalf of the Soviet Union. He told him that "the people I could introduce you to are very serious." Maclean agreed to met Deutsch. He was told to carry a book with a bright yellow cover into a particular café at a certain time. Deutsch was impressed with Maclean who he described as being "very serious and aloof" with "good connections". Maclean was given the codename "Orphan". (Maclean was also ordered to give up his communist friends.

In May 1934 Philby arranged for Deutsch to meet Guy Burgess. At first Deutsch rejected Burgess as a potential spy. He reported to headquarters that Burgess was "very smart... but a bit superficial and could let slip in some circumstances." Burgess began to suspect that his friend Maclean was working for the Soviets. He told Maclean: "Do you think that I believe for even one jot that you have stopped being a communist? You're simply up to something." When Maclean told Deutsch about the conversation, he reluctantly signed him up. Burgess went around telling anyone who would listen that he had swapped Karl Marx for Benito Mussolini and was now a devotee of Italian fascism. Burgess along with Philby joined the also joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, a pro-fascist society formed in 1935 to foster closer understanding with Adolf Hitler.

Guy Burgess now suggested the recruitment of one of his friends, Anthony Blunt. Later, he claimed that he could not remember the date when he became a Soviet spy. John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988), has carried out a special study of the subject: "Since the consensus of American intelligence opinion is that the actual closing would have taken place outside England, it is likely to have occurred in the spring of 1934, when Blunt was traveling through France and Austria en route to Italy."

Other friends, John Cairncross and Michael Straight were also recruited during this period. Arnold Deutsch handled recruitment but much of the day-to-day management of the spies were carried out by another agent, Theodore Maly. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he studied theology and became a priest but on the outbreak of the First World War he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army. He told Elsa Poretsky, the wife of Ignaz Reiss: "During the war I was a chaplain, I had just been ordained as a priest. I was taken prisoner in the Carpathians. I saw all the horrors, young men with frozen limbs dying in the trenches. I was moved from one camp to another and starved along with other prisoners. We were all covered with vermin and many were dying of typhus. I lost my faith in God and when the revolution broke out I joined the Bolsheviks. I broke with my past completely. I was no longer a Hungarian, a priest, a Christian, even anyone's son. I became a Communist and have always remained one."

As Ben Macintyre, the author of A Spy Among Friends (2014), has pointed out: "For a spy, Maly was conspicuous, standing six feet four inches tall, with a shiny grey complexion", and gold fillings in his front teeth. But he was a most subtle controller, who shared Deutsch's admiration for Philby." Maly described Philby as "an inspirational figure, a true comrade and idealist." According to Deutsch: "Both of them (Philby and Maly) were intelligent and experienced professionals, as well as genuinely very good people."

Christopher Andrew has argued in his book, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "KGB files credit Deutsch with the recruitment of twenty agents during his time in Britain. The most successful, however, were the Cambridge Five: Philby, Maclean, Burgess, Blunt and Cairncross.... All were committed ideological spies inspired by the myth-image of Stalin's Russia as a worker-peasant state with social justice for all rather than by the reality of a brutal dictatorship with the largest peacetime gulag in European history. Deutsch shared the same visionary faith as his Cambridge recruits in the future of a human race freed from the exploitation and alienation of the capitalist system. His message of liberation had all the greater appeal for the Five because it had a sexual as well as a political dimension. All were rebels against the strict sexual mores as well as the antiquated class system of inter war Britain. Burgess and Blunt were gay and Maclean bisexual at a time when homosexual relations, even between consenting adults, were illegal. Cairncross, like Philby a committed heterosexual, later wrote a history of polygamy."

On the outbreak of the Second World War Blunt joined the British Army. In 1939 he was sent to France where he served with the Army Intelligence Corps. When the German Army invaded in May 1940 he returned to England. Soon afterwards he was recruited by MI5. Blunt was placed in charge of the section that dealt with examining the communications of foreign embassies. This enabled him to pass valuable information to the Soviet Union. He later became the personal assistant to Guy Liddell, Deputy Director-General of MI5.

In early 1941 managed to help Tomás Harris, possibly another Soviet spy, to join MI5. (23) Later that year Harris established a social group of younger Secret and Security Service officers in both intelligence and special intelligence that met at his home at 6 Chesterfield Gardens. Other members included Blunt, Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Victor Rothschild, Guy Liddell,Richard Brooman-White, Tim Milne and Peter Wilson. "They were known among themselves simply as the Group, and they met in a magnificent house at 6 Chesterfield Gardens, the home of one Tomas Harris... Tomas had inherited much of his father's artistic talent, as he had inherited the house and his father's fortune."

Philby later explained he was a regular visitor to 6 Chesterfield Gardens and asked his friend if he could get him a job with British intelligence: "It was now more than ever necessary for me to get away from the rhododendrons of Beaulieu. I had to find a better hole with all speed. A promising chance soon presented itself. During my occasional visits to London, I had made a point of calling at Tomás Harris's house in Chesterfield Gardens, where he lived surrounded by his art treasures in an atmosphere of haute cuisine and grand vin. He maintained that no really good table could be spoiled by wine-stains. I have already explained that Harris had joined M15 after the break-up of the training-school at Brickendonbury."

In 1944 Blunt was responsible for liaison between MI5 and Allied Supreme Headquarters concerning the invasion of Europe. Blunt became involved in what became known as the Double-Cross System. Created by John Masterman, it attempted to "influence enemy plans by the answers sent to the enemy (by the double agents)" and to "deceive the enemy about our plans and intentions". Blunt also played a part in the deception plans for the D-Day landings. The key aims of the deception were: "(a) To induce the German Command to believe that the main assault and follow up will be in or east of the Pas de Calais area, thereby encouraging the enemy to maintain or increase the strength of his air and ground forces and his fortifications there at the expense of other areas, particularly of the Caen area in Normandy. (b) To keep the enemy in doubt as to the date and time of the actual assault. (c) During and after the main assault, to contain the largest possible German land and air forces in or east of the Pas de Calais for at least fourteen days."

John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988) has explained that Blunt worked with Tomás Harris and Juan Pujol García (Garbo) in this operation: "To reinforce this deception, Blunt and Harris had Garbo invent a subsidiary agent who supposedly operated in the Dover area. This agent was a disaffected Welsh nationalist seaman, code-named Donny. He provided a steady stream of sightings of American and Canadian troops assembling in the vicinity of England's principal channel port. His reports continued even after Allied troops had landed on the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. This contributed to the German High Command's decision to recall divisions already on their way south, in anticipation of a second and bigger operation taking place in the Pas de Calais."

At the end of the war Anthony Blunt went on a secret mission for the Royal family. According to Hugh Trevor-Roper, Blunt had been sent to retrieve documents that were believed to be in the hands of the royal family's many German relations. It was feared that the contents of these letters would be published in American newspapers. Blunt told Trevor-Roper that his mission had been successful and gave him some of the details of what was in the letters. It was clear that Blunt had made himself familiar with the contents of these papers.

It has been claimed that these documents included letters from the Duke of Windsor to Adolf Hitler. It has even been suggested that there was evidence in these documents that Windsor might have provided information about Britain's war plans: "This plan required the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to advance northward in the event of a German invasion of Belgium... The Ardennes was precisely the sector where General Guderian's XIX Panzer Group burst through on May 10, when Hitler unleashed his offensive in the West. This fact raises the possibility of a connection between the Duke of Windsor's activities at Allied GCHQ and the German decision of February 1940 to scrap their original attack plan in favor of a bold drive through the Ardennes to the Belgian coast so as to cut off the British forces."

These documents also showed that Windsor was close to breaking with his brother, King George VI, and moving to Nazi Germany. However, according to a telegram from Eberhard von Stohrer to Berlin, Windsor changed his mind the British media would "let loose upon himself the propaganda of his British enemies which would rob him of all prestige for the moment of possible intervention". Donald Cameron Watt, who has examined the Duke of Windsor section of the German Foreign Ministry files and says that important documents that refer to the Windsors' meeting with Hitler at Berchtesgaden are missing.

A few months later Blunt retired from MI5 to become Surveyor of the King's Pictures. This seemed to be a strange decision as it now meant that he could no longer be much use to his Soviet masters. Blunt later argued that "from 1945 I ceased to pass information to the Russians". The reason he gave was that he began to doubt that the Soviet regime "was following the true principles of Marxism." John Costello has argued that the Soviets would only have sanctioned Blunt's move from MI5 only if two conditions were satisfied: "(i) Moscow already had in MI5 another agent - or agents - of equivalent seniority and access. (ii) Blunt convinced Moscow that he would continue providing high-level intelligence about the British government."

Costello goes on to suggest that the KGB gave permission for Blunt to work for the royal family because it was in their interest to do so. "Once Blunt gained knowledge of the explosive royal secret, it became his gold-plated insurance policy. Even if his espionage was uncovered, Blunt would argue, his crime paled before the enormity of Windsor's wartime activities. And given the lengths to which the British government was willing to go to cover up these activities, Blunt would have been able to make a convincing case that he had a cast-iron guarantee against ever being publicly exposed. The Kremlin must also have appreciated that, in the Palace, Blunt could also provide a safety net for the other Cambridge agents. No one Blunt had recruited could ever be brought to public trial in Britain without implicating Blunt. Again, to expose Blunt would threaten the Windsor secret."

He continued to be a member of the spy ring led by Kim Philby and in May 1951 helped Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean to defect to the Soviet Union. The KGB feared that this would lead to the arrests of other members of the network. Blunt was ordered to go through Burgess's flat, searching for and destroying incriminating documents. He failed, however, to notice a series of unsigned notes describing confidential discussions in Whitehall in 1939. During this investigation, MI5, they interviewed Sir John Colville, one of those mentioned in the notes. He was able to identify the author as John Cairncross.

MI5 began surveillance of Cairncross and followed him to a meeting with Yuri Modin. Just in time, Modin noticed the surveillance and returned home without meeting Cairncross. Anthony Simkins was in charge of the operation and when he read the report that said Cairncross lit a cigarette, he exclaimed, "He's a non-smoker! He was smoking to warn his Soviet contact." Modin later told Cairncross how to handle the inevitable interrogation. "I told him to admit his Communist sympathies and an innocent friendship with Burgess and deny any link with espionage."

Cairncross was eventually interviewed by Arthur Martin and Jim Skardon, two senior MI5 officers. Cairncross denied being a spy but admitted to supplying information to Burgess. It was agreed that he should resign his post in the Treasury. Modin paid Cairncross "a large sum of money" and was encouraged to live abroad. Modin later recalled: "I liked Cairncross best of all our London agents. He wasn't an easy man to deal with, but he was a profoundly decent one"

Blunt, who had been seen in the company of Burgess and Maclean just before they disappeared. He was interviewed by MI5. Blunt admitted that his friendship with Burgess and Maclean meant he "was going to be a prime suspect". Moscow suggested he should "go to Russia". However, he refused, convinced that his "royal insurance policy" would protect him.

Blunt was interviewed eleven times by Arthur Martin and Jim Skardon but was eventually cleared of any involvement in their spying activities. When George VI died in 1953 Queen Elizabeth II asked Blunt to become Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures. He was also the author of several books including Art and Architecture in France, 1500–1700 (1953), Nicolas Poussin (1967), Sicilian Baroque (1968), Picasso's Guernica (1969) and Neapolitan Baroque and Rococo Architecture (1975).

Ever since Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean fled to Moscow, Kim Philby was suspected of being a Soviet agent. An old friend of Philby's, Flora Solomon, disapproved of what she considered were Philby's pro-Arab articles in The Observer. It has been argued that "her love for Israel proved greater than her old socialist loyalties." (40) In August 1962, during a reception at the Weizmann Institute, she told Victor Rothschild, who had worked with MI6 during the Second World War and enjoyed close connections with Mossad, the Israeli intelligence service: "How is it that The Observer uses a man like Kim? Don't the know he's a Communist?" She then went on to tell Rothschild that she suspected that Philby and his friend, Tomas Harris, had been Soviet agents since the 1930s. "Those two were so close as to give me an intuitive feeling that Harris was more than a friend."

It was expected that Arthur Martin would be sent out to interview Kim Philby in Beirut at the beginning of 1963. However, it was decided to send Philby's friend and former SIS colleague Nicholas Elliott instead. According to Philby's later version of events given to the KGB after he escaped to Moscow, Elliott told him: "You stopped working for them (the Russians) in 1949, I'm absolutely certain of that... I can understand people who worked for the Soviet Union, say before or during the war. But by 1949 a man of your intellect and your spirit had to see that all the rumours about Stalin's monstrous behaviour were not rumours, they were the truth... You decided to break with the USSR... Therefore I can give you my word and that of Dick White that you will get full immunity, you will be pardoned, but only if you tell it yourself. We need your collaboration, your help."

Roger Hollis wrote to J. Edgar Hoover on 18th January 1963, about Elliott's discussions with Kim Philby: "In our judgment Philby's statement of the association with the RIS is substantially true. It accords with all the available evidence in our possession and we have no evidence pointing to a continuation of his activities on behalf of the RIS after 1946, save in the isolated instance of Maclean. If this is so, it follows that damage to United States interests will have been confined to the period of the Second World War." This statement was undermined by the decision of Philby to flee to the Soviet Union a week later.

It later emerged that Philby met Yuri Modin in Beirut just before he defected. Modin had been the KGB controller for Blunt, Philby, Burgess and Maclean. Modin later wrote: "To my mind the whole business was politically engineered. The British government had nothing to gain by prosecuting Philby. A major trial, to the inevitable accompaniment of spectacular revelation and scandal, would have shaken the British establishment to its foundations... the secret service had actively encouraged him to slip away... spiriting Philby out of Lebanon was child's play."

Anthony Blunt was also in the Lebanon when Philby defected. He stayed with his old friend, Moore Crosthwaite, the British ambassador in Beirut. "The possibility therefore exists that Modin met Blunt to tell him of the immunity deal offered to Philby. Blunt would have returned to London fortified by the knowledge that with Philby in Moscow, if MI5 ever obtained hard evidence against him, it would offer him the same secret immunity deal. The thought would have reassured him. He would never need to flee to Moscow or spend the rest of his life in prison."

On 4th June 1963, Michael Straight was offered the post of the chairmanship of the Advisory Council on the Arts by President John F. Kennedy. Aware that he would be vetted - and his background investigated - he approached Arthur Schlesinger, one of Kennedy's advisers, and told him that Anthony Blunt had recruited him as a spy while an undergraduate at Trinity College. Schlesinger suggested that he told his story to the FBI. He spent the next couple of days being interviewed by William Sullivan.

Straight's information was passed on to MI5 and Arthur Martin, the intelligence agency's principal molehunter, went to America to interview him. Michael Straight confirmed the story, and agreed to testify in a British court if necessary. Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) has argued that Straight's information was "the decisive breakthrough in MI5's investigation of Anthony Blunt".

Peter Wright, who took part in the meetings about Anthony Blunt, argues in his book, Spycatcher (1987) that Roger Hollis decided to give Blunt immunity from prosecution because of his hostility towards the Labour Party and the damage it would do to the Conservative Party: "Hollis and many of his senior staff were acutely aware of the damage any public revelation of Blunt's activities might do themselves, to MI5, and to the incumbent Conservative Government. Harold Macmillan had finally resigned after a succession of security scandals, culminating in the Profumo affair. Hollis made little secret of his hostility to the Labour Party, then riding high in public opinion, and realized only too well that a scandal on the scale that would be provoked by Blunt's prosecution would surely bring the tottering Government down."

Anthony Blunt was interviewed by Arthur Martin at the Courtauld Institute on 23rd April 1964. Martin later wrote that when he mentioned Straight's name he "noticed that by this time Blunt's right cheek was twitching a good deal". Martin offered Blunt "an absolute assurance that no action would be taken against him if he now told the truth". Martin recalled: "He went out of the room, got himself a drink, came back and stood at the tall window looking out on Portman Square. I gave him several minutes of silence and then appealed to him to get it off his chest. He came back to his chair and confessed." He admitted being a Soviet agent and named twelve other associates as spies including Michael Straight, John Cairncross, Bernard Floud, Jenifer Hart, Phoebe Pool, Leo Long and Peter Ashby. They were also given immunity from prosecution.

Arthur Martin was disappointed about the way Roger Hollis and the British government had decided not to put Anthony Blunt on trial. Martin once again began to argue that there was still a Soviet spy working at the centre of MI5 and that pressure should be put on Blunt to make a full confession. Hollis thought Martin's suggestion was highly damaging to the organization and ordered Martin to be suspended from duty for a fortnight. Martin offered to carry on with the questioning of Blunt from his home, but Hollis forbade it. As a result, Blunt was left alone for two weeks, and nobody knows what he did... Soon afterward, Hollis picked another quarrel with Martin, and though he was very senior, summarily sacked him. Martin believes that Hollis sacked him because he feared him, but his action did Hollis little good, whatever his motive."

Peter Wright now took over the questioning of Blunt. He later recalled: "although Blunt under pressure expanded his information, it always pointed at those who were either dead, long since retired, or else comfortably out of secret access and danger". Wright asked him about Alister Watson, who he was convinced was a spy. Watson was still engaged in secret scientific work for the Admiralty. Blunt told Wright he could never be a Whittaker Chambers. "It's so McCarthyite, naming names, informing witch-hunts." Wright told him that his acceptance of the immunity deal obligated him to play the role of Chambers.

Wright arranged a joint meeting with Blunt. Wright tried to persuade Blunt to name Watson as a spy. He refused to do that, but when Wright suggested that he would be given immunity if he confessed, Watson turned to Blunt and said: "You've been such a success, Anthony, and yet it was I who was the great hope at Cambridge. Cambridge was my whole life, but I had to go into secret work, and now it has ruined my life."

Wright claims in his book, Spycatcher (1987): "No one who listened to the interrogation or studied the transcripts was in any doubt that Watson had been a spy, probably since 1938. Given his access to antisubmarine-detection research, he was, in my view, in particular, clinched the case. Watson told a long story about Kondrashev. He had met him, but did not care for him. He described Kondrashev in great detail. He was too bourgeois, claimed Watson. He wore flannel trousers and a blue blazer, and walked a poodle. They had a row and they stopped meeting."

Wright claims that this fits in with what the Soviet defector, Anatoli Golitsin, had told MI5. "He (Golitsin) said Kondrashev was sent to Britain to run two very important spies - one in the Navy and one in MI6. The MI6 spy was definitely George Blake... Golitsin said Kondrashev fell out with the Naval spy. The spy objected to his bourgeois habits, and refused to meet him. Golitsin recalled that as a result Korovin, the former London KGB resident, was forced to return to London to replace Kondrashev as the Naval spy's controller. It was obviously Watson."

As John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988), has pointed out: "The immunity deal was a convenient but flawed solution for all concerned. It was predicated on the assumption by MI5 that Blunt would live up to his side of the bargain. That he would provide the full and detailed confession that they needed. Once Blunt had been given the guarantee against prosecution, it would be impossible to bring him or any of those he implicated to justice. The price of uncovering the Cambridge network was that none of its members could ever be called to account."

Dick White, the head of MI6, agreed with Martin that suspicions remained about the loyalty of Hollis and Mitchell. In November, 1964, White recruited him and immediately nominated Martin as his representative on the Fluency Committee, that was investigating the possibility of Soviet spies in British intelligence. The committee initially examined some 270 claims of Soviet penetration, which were later whittled down to twenty. It was claimed that these cases supported the claims made by Konstantin Volkov and Igor Gouzenko that there was a high-level agent in MI5.

The people who Blunt named were interviewed by MI5. Jenifer Hart admitted being a member of the Communist underground but denied being a Soviet spy. Bernard Floud was interviewed by Peter Wright. After being interrogated he returned home and committed suicide on 10th October, 1967. Phoebe Pool, threw herself under a subway train, after being interviewed by Wright. Martin Furnival Jones, the director-general of MI5, was concerned that the suicides would "ruin our image" and brought and end to the investigation of Soviet spies named by Blunt.

Blunt continued as Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures in 1972. He also taught at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Eight years after confessing to being a Soviet spy he was appointed Adviser of the Queens's Pictures and Drawings. A post he held until his retirement in 1978.

Blunt's role as a Soviet agent was exposed in Andrew Boyle's book, The Climate of Treason in 1979. This resulted in his knighthood, awarded in 1956, being annulled. Margaret Thatcher told the House of Commons that: "It was considered important to gain Blunt's cooperation in the continuing investigations by the security authorities, following the defections of Burgess, Maclean and Philby, into Soviet penetration of the security and intelligence services and other public services during and after the war. Accordingly the Attorney-General authorized the offer of immunity to Blunt if he confessed. The Queen's Private Secretary was informed both of Blunt's confession and of the immunity from prosecution, on the basis of which it had been made. Blunt was not required to resign his appointment in the Royal Household, which was unpaid. It carried with it no access to classified information and no risk to security and the security authorities thought it desirable not to put at risk his cooperation."

Michael Kitson believes that Anthony Blunt was badly treated after the government statement: "The press, radio, and television began a campaign of vilification. Wild rumours accused him of spying for the Germans, of authenticating fakes, of salting away a fortune abroad; he was caricatured as snobbish, imperious, sexually predatory... Undoubtedly some of the agitation was motivated by Blunt's intellectuality and homosexuality as well as by class hatred. It is a striking fact that both Blunt's own actions and the treatment of him not only by the public but also by officials were pervaded at every turn by the class divisions in British society."