Religion and Slavery

Except for the Society of Friends, all religious groups in America supported slavery. In the South black people were not usually allowed to attend church services. Those churches that did accept them would segregate them from white worshipers.

One of the main reasons why masters did not want their slaves to become Christians involved the Bible. They feared that slaves might interpret the teachings of Jesus Christ as being in favour of equality. This was one of the main reasons why most plantation owners did what they could to stop their slaves from learning to read.

Slaves were also forbidden from continuing with African religious rituals. Drums were also banned as overseers worried that they would be used to send messages. They were particularly concerned that they would be used to signal a slave uprising.

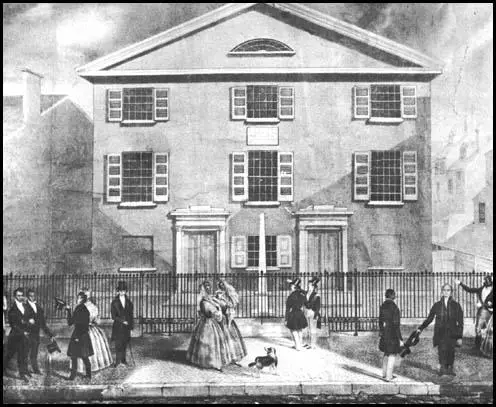

Black people in the North were much more likely to attend church services. In 1794 Richard Allen founded the first church for black people in Philadelphia. Two years later Peter Williams, a wealthy tobacco merchant who felt unwelcome in the local Methodist Church, established a similar church in New York.

In 1816 a group of churchmen led by Richard Allen formed the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Allen became the church's first bishop.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) William Wells Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

Slaveholders hide themselves behind the church. A more praying, preaching, psalm-singing people cannot be found than the slaveholders at the south. The religion of the south is referred to every day, to prove that slaveholders are good, pious men. But with all their pretensions, and all the aid which they get from the northern church, they cannot succeed in deceiving the Christian portion of the world. Their child-robbing, man-stealing, woman-whipping, chain-forging, marriage-destroying, slave-manufacturing, man-slaying religion, will not be received as genuine; and the people of the free states cannot expect to live in union with slaveholders, without becoming contaminated with slavery.

The American slave-trader, with the constitution in his hat and his license in his pocket, marches his gang of chained men and women under the very eaves of the nation's capitol. And this, too, in a country professing to be the freest nation in the world. They profess to be democrats, republicans, and to believe in the natural equality of men; that they are "all created with certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." They call themselves a Christian nation; they rob three millions of their countrymen of their liberties, and then talk of their piety, their democracy, and their love of liberty.

(2) Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

A clergyman who goes to the south, for the first time, has usually some feeling, however vague, that slavery is wrong. The slaveholder suspects this, and plays his game accordingly. He makes himself as agreeable as possible; talks on theology, and other kindred topics. The southerner invites him to talk with these slaves. He asks them if they want to be free, and they say, "O, no, massa." This is sufficient to satisfy him. He comes home to publish a "South-Side View of Slavery," and to complain of the exaggerations of abolitionists. He assures people that he has been to the south, and seen slavery for himself; that it is a beautiful "patriarchal institution;" that the slaves don't want their freedom; that they have hallelujah meetings, and other religious privileges.

What does he know of the half-starved wretches toiling from dawn till dark on the plantations? of mothers shrieking for their children, torn from their arms by slave traders? of young girls dragged down into moral filth? of pools of blood around the whipping post? of hounds trained to tear human flesh? of men screwed into cotton gins to die? The slaveholder showed him none of these things, and the slaves dared not tell of them if he had asked them.

(3) Moses Roper, Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper (1838)

There are several circumstances which occurred on this estate while I was there, relative to other slaves, which it may be interesting to mention. Hardly a day ever passed without some one being flogged. To one of his female slaves he had given a dose of castor oil and salts together, as much as she could take; he then got a box, about six feet by two and a half, and one and a half feet deep; he put this slave under the box, and made the men fetch as many stones as they could get, and put them on the top of it; under this she was made to stay all night. I believe, that if he had given this slave one, he had given her three thousand lashes. Mr. Gooch was a member of a Baptist church. His slaves, thinking him a very bad sample of what a professing Christian ought to be, would not join the connection he belonged to, thinking they must be a very bad set of people; there were many of them members of the Methodist church. On Sunday, the slaves can only go to church at the will of their master, when he gives them a pass for the time they are to be out. If they are found by the patrol after the time to which their pass extends, they are severely flogged.

(4) Austin Steward, Twenty-Two Years a Slave (1857)

Some have attempted to apologize for the enslaving of the Negro, by saying that they are inferior to the Anglo-Saxon race in every respect. This charge I deny; it is utterly false. Does not the Bible inform us that "God hath created of one blood all the nations of the earth?" And certainly in stature and physical force the colored man is quite equal to his white brother, and in many instances his superior; but were it otherwise, I can not see why the more favored class should enslave the other. True, God has given to the African a darker complexion than to his white brother: still, each have the same desires and aspirations. The food required for the sustenance of one is equally necessary for the other. Naturally or physically, they alike require to be warmed by the cheerful fire, when chilled by our northern winter's breath; and alike they welcome the cool spring and the delightful shade of summer. Hence, I have come to the conclusion that God created all men free and equal, and placed them upon this earth to do good and benefit each other, and that war and slavery should be banished from the face of the earth.

(5) Walter Hawkins escaped from slavery in Maryland and joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. He recorded these events in his book, From Slavery to Bishopric (1891)

One can well imagine the feelings of this young man, who had never seen such a large number of his race congregated into one town or city as freed men. However, the old preacher Proctor, in whose house he found a refuge, and who introduced him to his elder brother, kept him for a few weeks, feeding both his mind and body. Such was the old man's intense love to Christ and devotion to charitable works that, whoever came in his company, was made to feel a like affection for One whom the ages have been slow to comprehend. Before the end of the second week Hawkins felt that old Proctor's influence was irresistible; at last, while listening to one of his sermons, the young man became penitent, and threw in his lot with the Christians, and resolved that "this people shall be my people, and their God shall be my God".

As a slave, his religion was mere emotionalism, which served to break the monotony of the cruel scourge of slavery. But as a freed man he had an opportunity of reflecting upon the character of Christ, which had been clouded by the moral degradation which pervaded all rank of the society from whence he had made his escape. In that society vice reigned, yet it was believed to be under the special protection of Christianity - we mean the vice of breeding slaves and encouraging drunkenness and the like.

(6) Francis Fredric was helped by a Quaker to escape from his plantation in Kentucky. He wrote about it in his book Fifty Years of Slavery (1863)

Since my first attempt to escape I was so uniformly treated badly, that my life would have been insupportable if I had not been soothed by the kind words of the good abolitionist planter who had first conveyed to me a true knowledge of religion. I had been flogged, and went one day to show him the state in which I was. He asked me what I wanted him to do. I said, "To get me away to Canada."

He sat for full twenty minutes thoughtfully, and at last said, "Now, if I promise to take you away out of all this, you must not mention a word to any one. Don't breathe a syllable to your mother or sisters, or it will be betrayed." Oh, how my heart jumped for joy at this promise. I felt new life come into me. Visions of happiness flitted before my mind. And then I thought before the next day he might change his mind, and I was miserable again. I solemnly assured him I would say nothing to any one. "Come to me," he said, "on the Friday night about ten or eleven o'clock; I will wait till you come. Don't bring any clothes with you except those you have on. But bring any money you can get." I said I would obey him in every respect.

I went home and passed an anxious day. I walked out to my poor old mother's hut, and saw her and my sisters. How I longed to tell them, and bid them farewell. I hesitated several times when I thought I should never see them more. I turned back again and again to look at my mother. I knew she would be flogged, old as she was, for my escaping. I could foresee how my master would stand over her with the lash to extort from her my hiding-place. I was her only son left. How she would suffer torture on my account, and be distressed that I had left her for ever until we should meet hereafter in heaven I hoped.

At length I walked rapidly away, as if to leave my thoughts behind me, and arrived at my kind benefactor's house a little after eleven o'clock. He said but little, and seemed restless. He took some rugs and laid them at the bottom of the waggon, and covered me with some more. Soon we were on our way to Maysville, which was about twenty miles from his house. The horses trotted on rapidly, and I lay overjoyed at my chance of escape. When we stopped at Maysville, I remained for some time perfectly quiet, listening to every sound. At last I heard a gentleman's voice, saying, "Where is he? where is he?" and then he put in his hand and felt me. I started, but my benefactor told me it was all right, it was a friend. "This gentleman," he added, "will take care of you; you must go to his house." I got out of the waggon and shook my deliverer by the hand with a very, very grateful heart, you may be sure; for I knew the risk he had run on my account.

He wished me every success, and committed me to his friend, whom I accompanied to his house, and was received with the utmost kindness by his wife, who asked me if I was a Christian man. I answered yes. She took me up into a garret and brought me some food. Her little daughters shook hands with me. She spoke of the curse of slavery to the land. "I am an abolitionist," she said, "although in a slaveholding country. The work of the Lord will not go on as long as slavery is carried on here." Every possible attention was paid to me to soothe my troubled mind. The following night the gentleman and his son left the house about ten o'clock. A little after twelve o'clock the gentleman returned, and said he had got a boat and I was to go with him. His lady bid me farewell, and told me to put my trust in the Lord, in whose hands my friends were, and asked me to remember them in my prayers, since they had hazarded everything for me, and, if discovered, they would be cruelly treated. I was soon rowed across the river, which is about a mile wide in that place.

The son remained with me in the skiff whilst his father went to a neighbouring village to bring some one to take charge of me. After some time, he brought a friend, who told me never to mention the name of any one who had helped me. He took me to his house outside the town, where I had some refreshment, and remained about half-an-hour. A waggon came up, and I was stowed away, and driven about twenty miles that night, being well guarded by eight or ten young men with revolvers.

It would do any real Christian man good to see the enthusiasm and determination of these young Abolitionists. Their whole heart and soul are in the work. A dozen such men would have defied a hundred slaveholders. From having seen over and over again slaves dragged back chained through their country, and having heard the tales of horrible treatment of the poor hopeless captives, some having been flogged to death, others burnt alive, with their heads downwards, over a slow fire, others covered with tar and set on fire, these noble, courageous, self-sacrificing men have been so wrought upon, that they are heroes of the highest stamp, and I verily believe they would willingly lay down their lives rather than allow one fugitive slave to be taken from them.

(7) Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave (1831)

The Moravian ladies (Mrs. Richter, Mrs. Olufsen, and Mrs. Sauter) taught me to read in the class; and I got on very fast. In this class there were all sorts of people, old and young, grey headed folks and children; but most of them were free people. After we had done spelling, we tried to read in the Bible. After the reading was over, the missionary gave out a hymn for us to sing. I dearly loved to go to the church, it was so solemn. I never knew rightly that I had much sin till I went there. When I found out that I was a great sinner, I was very sorely grieved, and very much frightened. I used to pray God to pardon my sins for Christ's sake, and forgive me for every thing I had done amiss; and when I went home to my work, I always thought about what I had heard from the missionaries, and wished to be good that I might go to heaven.

(8) James Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith (1859)

Neither my master or any other master, within my acquaintance, made any provisions for the religious instruction of his slaves. They were not worked on the Sabbath. One of the "boys" was required to stay at home and "feed," that is, take care of the stock, every Sabbath; the rest went to see their friends. Those men whose families were on other plantations usually spent the Sabbath with them; some would lie about at home and rest themselves.

When it was pleasant weather my master would ride "into town" to church, but I never knew him to say a word to one of us about going to church, or about our obligations to God, or a future state. But there were a number of pious slaves in our neighborhood, and several of these my master owned; one of these was an exhorter. He was not connected with a religious body, but used to speak every Sabbath in some part of the neighborhood. When slaves died, their remains were usually consigned to the grave without any ceremony; but this old gentleman, wherever he heard of a slave having been buried in that way, would send notice from plantation to plantation, calling the slaves together at the grave on the Sabbath, where he'd sing, pray, and exhort. I have known him to go ten or fifteen miles voluntarily to attend these services. He could not read, and I never heard him refer to any Scripture, and state and discourse upon any fundamental doctrine of the gospel; but he knew a number of "spiritual songs by heart," of these he would give two lines at a time very exact, set and lead the tune himself; he would pray with great fervor, and his exhortations were amongst the most impressive I have heard.