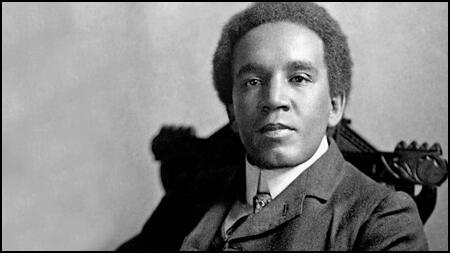

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was born in Holban, London, on 15th August, 1875. His father, Daniel Taylor, came to England from Sierra Leone to study medicine. After graduating he found his race was a barrier to maintaining a medical practice in England. He therefore decided to return to Sierra Leone, soon after Samuel was born.

Samuel was raised by his mother, Alice Taylor. Named after the poet Samuel Coleridge, he took a keen interest in music and at the age of 15 applied to enter the Royal College of Music (RCM). Sir George Grove, the principal of the RCM, originally said no as he feared other students might complain about having to study with a black man.

In 1896 he met Paul Laurence Dunbar. The son of a former slave, Dunbar had written a great deal of poetry about Africa. He decided to set some of Dunbar's poems to music and African Romances was published in 1897.

Edward Elgar, Britain's leading composer, was very impressed with Samuel Coleridge Taylor's work. He wrote that he was "far and away the cleverest fellow amongst the young men" in the country. This was reinforced by the first performance of Hiawatha's Wedding Feast (1899). It was an immediate success and for the next ten years was the country's most popular English choral-orchestral work. This was followed by Ethiopia Saluting the Colours (1902), Four African Dances (1902) and Twenty-Four Negro Melodies (1904).

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was a leading exponent of Pan-Africanism, which emphasized the importance of a shared African heritage. Along with his friend Duse Mohammed, he founded The African and Orient Review, a Pan-Africanist newspaper in London. In 1904 he wrote about his work Twenty-Four Negro Melodies: "What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvorak for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro Melodies."

While living in Croydon he experienced a great deal of racial prejudice. Samuel Coleridge Taylor's white wife (Jessie Walmisley) was also a target of abuse when she was out walking with her husband. His daughter later reported that gangs of local youths would often make comments about the colour of his skin: "When he saw them approaching along the street he held my hand more tightly, gripping it until it almost hurt."

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was unable to survive on his royalties and in 1903 he became professor of composition at Trinity College of Music in London. He also worked as a conductor and several times toured the United States. After reading The Souls of Black Folk by William Du Bois he took a keen interest in politics. While in America he met and had discussions with Booker T. Washington and Theodore Roosevelt. In 1906 he gave concerts in several cities including New York, Boston, St Louis, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Washington and Chicago.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor died of pneumonia on 1st September, 1912. His two children, Hiawatha and Avril, both had distinguished careers as composers and conductors.

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Coleridge Taylor, letter to Andrew Hilyer (14th September, 1904)

As for the prejudice, I am well prepared for it. Surely that which you and many others have lived in for so many years will not quite kill me. I am a great believer in my race, and I never lose an opportunity of letting my white friends here know it. Please don't make any arrangements to wrap me in cotton-wool.

(2) Samuel Coleridge Taylor, programme notes for the production of Twenty-Four Negro Melodies (1904)

What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvorak for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro Melodies.

(3) In February, 1912, Samuel Coleridge Taylor, read about racist remarks made by a visiting lecturer at the Putney Debating Society. A letter of complaint was published in the Croydon Guardian on 10th February, 1912.

It is amazing that grown-up, and presumably educated people, can listen to such primitive and ignorant nonsense-mongers, who are men without vision, utterly incapable of penetrating beneath the surface of things

There is an appalling amount of ignorance amongst English people regarding the Negro and his doings. Personally, I consider myself the equal of any white man who ever lived, and no one could change me in that respect; on the other hand, no man reverences worth more than I, irrespective of colour and creed. May I further remind the lecturer that really great people always see the best in others; it is the little man who looks for the worst - and finds it.

It was an arrogant 'little' white man who dared to say to the great Dumas, 'and I hear you actually have negro blood in you!' 'Yes', said the witty writer; 'My father was a Mulatto, his father a Negro, and his father a monkey. My ancestry begins where yours ends!' Somehow I always manage to remember that wonderful answer when I meet a certain type of white man (a type, thank goodness! as far removed from the best as the Poles from each other) and the remembrance makes me feel quite happy- wickedly happy, in fact!'

(4) Samuel Coleridge Taylor, African Times and Orient Review (July, 1912)

There is, of course, a large section of the British people interested in the coloured races; but it is, generally speaking, a commercial interest only. Some of these may possibly be interested in the aims and desires of the coloured peoples; but, taking them on a whole, I fancy one accomplished fact carries far more weight than a thousand aims and desires, regrettable though it may be.

Therefore, it is imperative that this venture be heartily supported by the coloured people themselves, so that it shall be absolutely independent of the whites as regards circulation. Such independence will probably speak to the average Britisher far more than anything else, and will ultimately arouse his attention and interest - even to his support.

(5) Blyden Jackson, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1969)

American Negroes who were born in the earlier years of this century grew up in black communities where the name of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was as well known then as now are such names as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Gentle as he was in manner, refined as was his calling, he was still a fierce apostle of human liberty and a crusader for the rights of man. He was a parable for the black consciousness of our present time.