On this day on 25th February

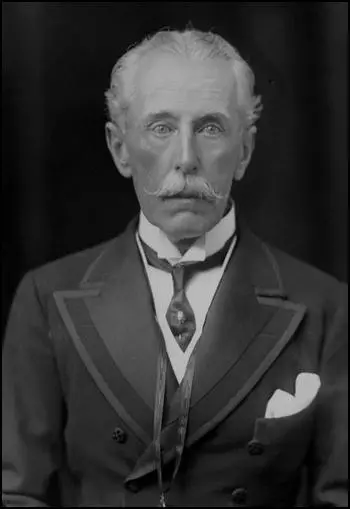

On this day in 1854 diplomat George Buchanan, the fifth son of Sir Andrew Buchanan and his wife, Frances Mellish, was born in Copenhagen on 25th February 1854. The son of the British Ambassador in Denmark, Buchanan was educated at Wellington College.

Buchanan entered the diplomatic service in 1876. After serving first as attaché under his father, who was then ambassador at Vienna, he transferred successively to Rome (1878) and Tokyo (1879). On 25th February 1885 he married Lady Georgina Meriel Bathurst (1863–1922), daughter of Allen Alexander, sixth Earl Bathurst (1832–1892).

According to his biographer, Zara Steiner: "After periods at the Foreign Office and at Bern, in 1893 Buchanan became chargé d'affaires at Darmstadt, an important listening post as members of the Russian, German, and British royal families were frequent visitors there to the grand duke of Hesse and by Rhine; in this capacity he was brought into contact with Queen Victoria, owing to her close relationship with the Darmstadt court. In 1898 he served as the British agent on the Venezuela boundary arbitration tribunal at Paris and afterwards was secretary of the embassy at Rome (1900) and Berlin (1901). In 1903, with the rank of minister, he became agent and consul-general at Sofia, where he made his diplomatic reputation during the Near East crisis which followed the Turkish revolution, the annexation of Bosnia and Herzogovina, the proclamation of Bulgarian independence, and the recognition in 1908 of Prince Ferdinand as king. The agency became a legation and Buchanan, who enjoyed excellent relations with Ferdinand, was made envoy-extraordinary. He was awarded the Hague legation in 1908."

In 1910 Buchanan was appointed as the British Ambassador in Russia. His friend, Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Daily Chronicle, kept him informed of the political developments in Russia and arranged for his to meet some of the leading reformists in the country. He reported back to London on the different reformers. He said of Irakli Tsereteli: "Tsereteli had a refined and sympathetic personality. He attracted me by his transparent honesty of purpose and his straightforward manner. He was, like so many other Russian Socialists, an Idealist; but though I do not reproach him with this, he made the mistake of approaching grave problems of practical policies from a purely theoretical standpoint." Buchanan was much more concerned about the possible impact of Victor Chernov, a leading figure in the Socialist Revolutionary Party: "Chernov was a man of strong character and considerable ability. He belonged to the advanced wing of the SR party, and advocated the immediate nationalization of the land and the division among the peasants awaiting the decision of the Consistent Assembly. He was generally regarded as dangerous and untrustworthy."

Buchanan became a much more important figure in Russia in the build-up to the First World War. He sent regular reports to Sir Edward Grey, the British foreign minister. In July 1914 he wrote about negotiations with members of the Russian government: "As they both continued to press me to declare our complete solidarity with them, I said that I thought you might be prepared to represent strongly at Vienna and Berlin danger to European peace of an Austrian attack on Serbia. You might perhaps point out that it would in all probability force Russia to intervene, that this would bring Germany and France into the field, and that if war became general, it would be difficult for England to remain neutral. Minister for Foreign Affairs said that he hoped that we would in any case express strong reprobation of Austria's action. If war did break out, we would sooner or later be dragged into it, but if we did not make common cause with France and Russia from the outset we should have rendered war more likely."

Buchanan also became very concerned about the influence of Gregory Rasputin who was against Russian involvement in the war. It has been argued that Buchanan became involved with the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd, under the command Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Hoare. Members of this unit included Oswald Rayner, John Scale, Cudbert Thornhill and Stephen Alley. Hoare became friendly with Vladimir Purishkevich and in November 1916 he was told about the plot to "liquidate" Rasputin. Hoare later recalled that Purishkevich's tone "was so casual that I thought his words were symptomatic of what everyone was thinking and saying rather than the expression of a definitely thought-out plan."

John Scale recorded: "German intrigue was becoming more intense daily. Enemy agents were busy whispering of peace and hinting how to get it by creating disorder, rioting, etc. Things looked very black. Romania was collapsing, and Russia herself seemed weakening. The failure in communications, the shortness of foods, the sinister influence which seemed to be clogging the war machine, Rasputin the drunken debaucher influencing Russia's policy, what was to the be the end of it all?" Michael Smith, the author of Six: A History of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (2010) has argued: "The key link between the British secret service bureau in Petrograd and the Russians plotting Rasputin's demise was Rayner through his relationship with Prince Yusupov, the leader of the Russian plotters."

Gregory Rasputin was assassinated on 29th December, 1916. Soon afterwards Prince Felix Yusupov, Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, confessed to being involved in the killing.

Samuel Hoare reacted angrily when Tsar Nicholas II suggested to the British ambassador, George Buchanan, that Rayner, was involved in the plot to kill Rasputin. Hoare described the story as "incredible to the point of childishness". However, Michael Smith has speculated that Rayner was at the scene of the crime: "He (Rasputin) was shot several tunes, with three different weapons, with all the evidence suggesting that Rayner fired the final fatal shot, using his personal Webley revolver."

Buchanan began to fear that Tsar Nicholas II might be overthrown and urged him to bring in reforms. He reported on a meeting he had with the Tsar in January 1917: "I went on to say that there was now a barrier between him and his people, and that if Russia was still united as a nation it was in opposing his present policy. The people, who have rallied so splendidly round their Sovereign on the outbreak of war, had seen how hundreds of thousands of lives had been sacrificed on account of the lack of rifles and munitions; how, owing to the incompetence of the administration, there had been a severe food crisis." Buchanan urged the Tsar to take notice of what was being said in the Duma: "The Duma, I had reason to know, would be satisfied if His Majesty would but appoint as President of the Council a man whom both he and the nation could have confidence, and would allow him to choose his own colleagues."

Although a man of deeply held conservative views, Buchanan developed good relationships with liberal politicians in Russia during the revolution and welcomed the appointment of Prince George Lvov as head the new Provisional Government in Russia as he refused to withdraw the country from the First World War. He told the British government: "Lvov does not favour the idea of taking strong measures at present, either against the Soviet or the Socialist propaganda in the army. On my telling him that the Government would never be masters of the situation so long as they allowed themselves to be dictated to by a rival organization, he said that the Soviet would die a natural death, that the present agitation in the army would pass, and that the army would then be in a better position to help the Allies to win the war than it would have been under the old regime."

By the summer of 1917 Buchanan realised that the experiment in democracy was not working: "The military outlook is most discouraging. Nor do I take an optimistic view of the immediate future of the country. Russia is not ripe for a purely democratic form of government, and for the next few years we shall probably see a series of revolutions or counter-revolutions. A vast Empire like this, with all its different races, will not long hold together under a Republic. Disintegration will, in my opinion, sooner or later set in, even under a federal system."

Prince George Lvov was replaced by Alexander Kerenskyon 8th July, 1917. Buchanan reported back to London: "From the very first Kerensky had been the central figure of the revolutionary drama and had, alone among his colleagues, acquired a sensible hold on the masses. An ardent patriot, he desired to see Russia carry on the war till a democratic peace had been won; while he wanted to combat the forces of disorder so that his country should not fall a prey to anarchy. In the early stages of the revolution he displayed an energy and courage which marked him out as the one man capable of securing the attainment of these ends."

However, Buchanan, feared the growing support for the Bolsheviks: The Bolsheviks, who form a compact minority, have alone a definite political programme. They are more active and better organized than any other group, and until they and the ideas which they represent are finally squashed, the country will remain a prey to anarchy and disorder. If the Government are not strong enough to put down the Bolsheviks by force, at the risk of breaking altogether with the soviet, the only alternative will be a Bolshevik Government."

On 7th January, 1918, Buchanan returned to England. Buchanan was horrified by the Russian Revolution but recognised the talents of Lenin and Leon Trotsky. In his book, My Mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories (1923) he explained: "I readily admit that Lenin and Trotsky are both extraordinary men. The Ministers, in whose hands Russia had placed her destinies, had all proved to be weak and incapable, and now by some cruel turn of fate the only two really strong men whom she had produced during the war were destined to consummate her ruin. On their advent to power, however, they were still an unknown quantity, and nobody expected that they would have a long tenure of office."

George Buchanan died at his home, 15 Lennox Gardens, London, on 20th December 1924. He left one daughter, Meriel, who herself wrote on her experiences in Russia in a number of books, including Ambassador's Daughter (1958).

On this day in 1866 Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce was born in Pescasseroli, Italy. The Croce family were on the island of Ischia during the earthquake of 1883. Croce was buried in rubble but was rescued although his parents and sister died in the disaster.

Croce studied literature and philosophy in Rome and Naples and in 1902 published Estetica. The following year he established the journal La Critica.

In 1910 Croce became a senator and served as Minister of Education (1920-21). His left-wing political views resulted in him being ousted from public life by Benito Mussolini. He was also forced to resign his professorship at Naples.

Croce returned to public life after Italy surrendered to the Allies in June 1944 and joined the government formed by Invanoe Bonomi. He became a member of the Constituent Assembly and in 1947 was elected president of the Italian Liberal Party. Benedetto Croce died on 20th November 1952.

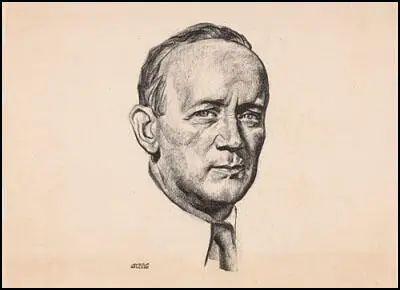

On this day in 1881 William Zebulon Foster was born in Taunton, Massachusetts. According to Theodore Draper: "His father, an English-hating Irish immigrant, washed carriages for a living. His mother, a devout Catholic of English-Scotch stock, bore twenty-three children, most of whom died; in infancy."

The family moved to Philadelphia in 1887. Foster later wrote that he grew up in a slum where "indolence, ignorance, thuggery, crime, disease, drunkenness and general social degeneration flourished." At the age of ten Foster was forced to leave school in search of work. After having several menial jobs in Pennsylvania he moved to New York City in 1900.

Foster joined the Socialist Party in 1901 and over the next few years worked as a cook, seaman, dock-worker, farm hand, trolley-car conductor, metal worker, car carpenter and airbrakeman. In 1904 he joined an extremist group headed by a physician, Dr. William F. Titus, "who preached an uncompromising version of faith in the revolutionary class struggle and scorn for all reforms." In 1910 he joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Foster was involved in the IWW free speech campaign and was imprisoned after a demonstration in Spokane.

Foster gradually emerged as was one of the leaders of the movement and in 1911 represented the IWW at the International Union Conference in Budapest. When Foster returned he argued that the IWW should disband so that its members could join and eventually capture the American Federation of Labour. When this was rejected, Foster left the IWW and formed the short-lived Syndicalist League of North America.

After the war, Foster, a railway car inspector in Chicago, joined the American Federation of Labour. He moved up the hierarchy and by 1920 he managed to persuade the AFL annual conference to pass a resolution in favour of government ownership of the railroads. The following year he supported John L. Lewis when he challenged Samuel Gompers for the presidency of the AFL.

In 1921 Earl Browder invited Foster to accompany him on a trip to Moscow to attend a conference of the Profintern. Foster was appointed the Profintern's agent in the United States and soon afterwards he joined the American Communist Party. At the time the party chairman was James Cannon, however, he was being challenged for this position by a group led by Charles Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone. Foster initially associated himself with Cannon.

It was decided that because Foster had a strong following in the trade union movement that he should be the party candidate in the 1924 Presidential Election. Benjamin Gitlow was chosen as his running-mate. Foster did not do well and only won 38,669 votes (0.1 of the total vote). This compared badly with the other left-wing candidate, Robert La Follette, of the Progressive Party, who obtained 4,831,706 votes (16.6%).

The American Communist Party continued to be divided into two factions. One group that included Charles Ruthenberg, Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe and Benjamin Gitlow, favoured a strategy of class warfare. Whereas Foster and James Cannon, believed that their efforts should concentrate on building a radicalised American Federation of Labor. Ruthenberg argued in an article published in Communist Labor: "The party must be ready to put into its program the definite statement that mass action culminates in open insurrection and armed conflict with the capitalist state. The party program and the party literature dealing with our program and policies should clearly express our position on this point. On this question there is no disagreement."

Foster retailated by arguing: "At heart and in their daily action the trade unions are revolutionary. Their unchangeable policy is to withhold from the exploiters all they have the power to. In these days, when they are weak in numbers and discipline, they have to content themselves with petty achievements. But they are constantly growing in strength and understanding, and the day will surely come when they will have the great masses of workers organized and instructed in their true interests. That hour will sound the death knell of capitalism. Then they will pit their enormous organization against the parasitic employing class, end the wages system forever and set up the long-hoped-for era of social justice. That is the true meaning of the trade union movement."

The Comintern eventually accepted the leadership of Charles Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone. As Theodore Draper pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "After the Comintern's verdict in favor of Ruthenberg as party leader, the factional storm gradually subsided.... At the Seventh Plenum at the end of 1926, the Comintern, for the first time in five years, found it unnecessary to appoint an American Commission to deal with an American factional struggle.... Ruthenberg's machine worked so smoothly and efficiently that it made those outside his inner circle increasingly restless. Beneath the surface of the factional lull, another rebellion smoldered, with the helpful encouragement of Cannon, who had touched off the anti-Ruthenberg rebellion three years earlier."

On the death of Charles Ruthenberg in 1927 Jay Lovestone became the party's national secretary. James Cannon, the chairman of the American Communist Party, attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928. While in the Soviet Union he was given a document written by Leon Trotsky on the rule of Joseph Stalin. Convinced by what he read, when he returned to the United States he criticized the Soviet government. As a result of his actions, Cannon and his followers were expelled from the party. Cannon now joined with other Trotskyists to form the Communist League of America.

Foster, who remained a strong supporter of Joseph Stalin and remained in the American Communist Party and was their candidate in the 1928 Presidential Election. Once again Foster did badly and only won 48,551 votes (0.1%). This time it was Norman Thomas of the Socialist Party that was supported by left-wing voters.

On March 16, 1929, Benjamin Gitlow was appointed to the post of Executive Secretary of the party. Max Bedacht and Earl Browder made-up the three men leadership team. By this time Joseph Stalin had placed his supporters in most of the important political positions in the country. Even the combined forces of all the senior Bolsheviks left alive since the Russian Revolution were not enough to pose a serious threat to Stalin.

In 1929 Nikolay Bukharin was deprived of the chairmanship of the Comintern and expelled from the Politburo by Stalin. He was worried that Bukharin had a strong following in the American Communist Party, and at a meeting of the Presidium in Moscow on 14th May he demanded that the party came under the control of the Comintern. He admitted that Jay Lovestone was "a capable and talented comrade," but immediately accused him of employing his capabilities "in factional scandal-mongering, in factional intrigue." Benjamin Gitlow and Ella Reeve Bloor defended Lovestone. This angered Stalin and according to Bertram Wolfe, he got to his feet and shouted: "Who do you think you are? Trotsky defied me. Where is he? Zinoviev defied me. Where is he? Bukharin defied me. Where is he? And you? When you get back to America, nobody will stay with you except your wives." Stalin then went onto warn the Americans that the Russians knew how to handle troublemakers: "There is plenty of room in our cemeteries."

Jay Lovestone realised that he would now be expelled from the American Communist Party. On 15th May, 1929 he sent a cable to Robert Minor and Jacob Stachel and asked them to take control over the party's property and other assets. However, as Theodore Draper has pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "The Comintern beat him to the punch. On May 17, even before the Comintern's Address could reach the United States, the Political Secretariat in Moscow decided to remove Lovestone, Gitlow, and Wolfe from all their leading positions, to purge the Political Committee of all members who refused to submit to the Comintern's decisions, and to warn Lovestone that it would be a gross violation of Comintern discipline to attempt to leave Russia."

William Z. Foster, who had already gone on record as saying, "I am for the Comintern from start to finish. I want to work with the Comintern, and if the Comintern finds itself criss-cross with my opinions, there is only one thing to do and that is to change my opinions to fit the policy of the Comintern", now became the dominant figure in the party. Jay Lovestone, Benjamin Gitlow, Bertram Wolfe and Charles Zimmerman, now formed a new party the Communist Party (Majority Group).

By 1929 the American Communist Party only had 7,000 members. Most of these were immigrants living in and around New York City. There were also a large number involved in the arts including Elia Kazan, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Howard Fast, Pete Seeger, Clifford Odets, Larry Parks, John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, Gale Sondergaard, Joseph Bromberg, Richard Wright, Dalton Trumbo, Richard Collins, Budd Schulberg, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Edwin Rolfe, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz, Paul Jarrico, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie.

The Great Depression helped the party grow and in the 1932 Presidential Election, the party candidate, Foster polled 102,991 votes (0.3), but Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party candidate, polled seven times that figure. Soon afterwards, Foster suffered a heart-attack and Earl Browder became the new leader of the American Communist Party. Foster moved to Moscow where he received treatment for his heart problems. He returned to the United States in 1935, but by this time Browder had established himself as the most important figure in the American Communist Party.

The leadership of the American Communist Party remained loyal to the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. It was argued that this was the best way to defeat fascism. However, this view took a terrible blow when on 28th August, 1939, Joseph Stalin signed a military alliance with Adolf Hitler. Browder and other leaders of the party decided to support the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

John Gates pointed out that this created serious problems for the party. "We turned on everyone who refused to go along with our new policy and who still considered Hitler the main foe. People whom we had revered only the day before, like Mrs. Roosevelt, we now reviled. This was one of the characteristics of Communists which people always found most difficult to swallow - that we could call them heroes one day and villains the next. Yet in all of this lay our one consistency; we supported Soviet policies whatever they might be; and this in turn explained so many of our inconsistencies. Immediately following the upheaval over the Soviet-German non-aggression pact came the Finnish war, which compounded all our difficulties since, here also, our position was uncritically in support of the Soviet action."

Earl Browder was the American Communist Party candidate in the 1940 Presidential Election, but the government imposed a court order forbidding him to travel within the country. His campaign efforts were limited to the issuing of written statement and the distribution of recorded speeches. In the election he won only 46,251 votes. Later that year he was found guilty of passport irregularities and sentenced to prison for four years. When the United States joined the Second World War and became allies with the Soviet Union, attitudes towards communism changed and Browder was released from prison after only serving 14 months of his sentence. Membership of the party also grew to 75,000.

In 1944 Earl Browder controversially announced that capitalism and communism could peacefully co-exist. As John Gates pointed out in his book, The Story of an American Communist (1959): "Browder had developed several bold ideas which were stimulated by the unprecedented situation, and now he proceeded to put them into effect. At a national convention in 1944, the Communist Party of the United States dissolved and reformed itself into the Communist Political Association." Ring Lardner, another party member, explained: "The change seemed only to bring the nomenclature in line with reality. Our political activities, by then, were virtually identical to those of our liberal friends."

Except for Foster and Benjamin Davis, the leaders of the American Communist Party unanimously supported Browder. However, in 1945, Jacques Duclos, a leading member of the French Communist Party and considered to be the main spokesman for Joseph Stalin, made a fierce attack on the ideas of Browder. As John Gates pointed out: " The leaders of the American Communists, who, except for Foster and one other, had unanimously supported Browder, now switched overnight, and, except for one or two with reservations, threw their support to Foster. An emergency convention in July, 1945, repudiated Browder's ideas, removed him from leadership and re-constituted the Communist Party in an atmosphere of hysteria and humiliating breast-beating unprecedented in communist history."

William Z. Foster now became the new chairman of the party. Two years later, after being criticised by leaders in the Soviet Union, Browder was expelled from the American Communist Party. He was later to argue: "The American Communists had thrived as champions of domestic reform. But when the Communists abandoned reforms and championed a Soviet Union openly contemptuous of America while predicting its quick collapse, the same party lost all its hard-won influence. It became merely a bad word in the American language."

On the morning of 20th July, 1948, Foster, and eleven other party leaders, included Eugene Dennis, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government". The trial began on 17th January, 1949. As John Gates pointed out: "There were eleven defendants, the twelfth, Foster, having been severed from the case because of his serious, chronic heart ailment."

It was difficult for the prosecution to prove that the eleven men had broken the Alien Registration Act, as none of the defendants had ever openly called for violence or had been involved in accumulating weapons for a proposed revolution. The prosecution therefore relied on passages from the work of Karl Marx and other revolution figures from the past. When John Gates refused to answer a question implicating other people, he was sentenced by Judge Harold Medina to 30 days in jail. When Henry M. Winston and Gus Hall protested, they were also sent to prison.

After a nine month trial the leaders of the American Communist Party were found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Robert G. Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years. They appealed to the Supreme Court but on 4th June, 1951, the judges ruled, 6-2, that the conviction was legal.

As John Gates pointed out in his book, The Story of an American Communist (1959): "To many in the leadership, this meant that the United States was unquestionably on the threshold of fascism. Had not Hitler's first step been to outlaw the Communist Party? We saw an almost exact parallel."

During the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. John Gates, the editor of The Daily Worker, became a supporter of Khrushchev and at his direction the newspaper printed the full text of Khrushchev's speech. This brought him into conflict with the leaders of the American Communist Party.

In April 1956 Eugene Dennis, published a report on the American Communist Party. As John Gates pointed out that it "was a devastating critique of the party's policies over a whole decade. Like all reports, it was not only his own, but had been discussed and approved by the National Committee members in advance. Dennis characterized the party's policies as super-leftist and sectarian, narrow-minded and inflexible, dogmatic and unrealistic." Foster, Benjamin Davis and Robert G. Thompson, constituted a minority of the leadership that led the attack on Dennis.

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

Some members of the American Communist Party were highly critical of the actions of Nikita Khrushchev and John Gates stated that "for the first time in all my years in the Party I felt ashamed of the name Communist". He then went on to add that "there was more liberty under Franco's fascism than there is in any communist country." As a result he was accused of being "right-winger, Social-Democrat, reformist, Browderite, peoples' capitalist, Trotskyist, Titoite, Stracheyite, revisionist, anti-Leninist, anti-party element, liquidationist, white chauvinist, national Communist, American exceptionalist, Lovestoneite, Bernsteinist".

Foster was a loyal supporter of the leadership of the Soviet Union and refused to condemn the regime's record on human rights. Foster failed to criticize the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. Large numbers left the party. At the end of the Second World War it had 75,000 members. By 1957 membership had dropped to 5,000.

On 22nd December, 1957, the American Communist Party Executive Committee decided to close down the Daily Worker. Gates argued: "Throughout the 34 years of its existence, the Daily Worker has withstood the attacks of Big Business, the McCarthyites and other reactionaries. It has taken a drive from within the party - conceived in blind factionalism and dogmatism - to do what our foes have never been able to accomplish. The party leadership must once and for all repudiate the Foster thesis, defend the paper and its political line, and seek to unite the entire party behind the paper."

Foster retired in 1957 and assumed the title of Chairman emeritus of the party. Gus Hall, also a loyal supporter of Stalinism, became the new leader of the party.

William Zebulon Foster died in Moscow on 1st September, 1961.

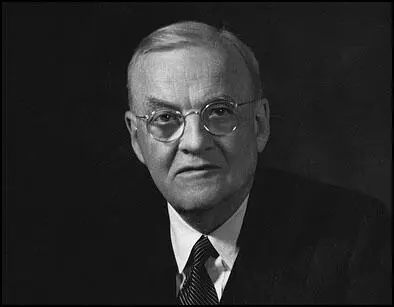

On this day in 1888 John Foster Dulles, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was born in Washington on 25th February, 1888. His brother was Allen Dulles and his grandfather was John Watson Foster, Secretary of State under President Benjamin Harrison. His uncle, Robert Lansing, was Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Woodrow Wilson.

After attending Princeton University and George Washington University he joined the New York law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell, where he specialized in international law. He tried to join the United States Army during the First World War but was rejected because of poor eyesight.

In 1918 Woodrow Wilson appointed Dulles as legal counsel to the United States delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference. Afterwards he served as a member of the War Reparations Committee. Dulles, a deeply religious man, attended numerous international conferences of churchmen during the 1920s and 1930s. He also became a partner in the Sullivan & Cromwell law firm.

Dulles was a close associate of Thomas E. Dewey who became the presidential candidate of the Republican Party in 1944. During the election Dulles served as Dewey's foreign policy adviser. In 1945 Dulles participated in the San Francisco Conference and worked as adviser to Arthur H. Vandenberg and helped draft the preamble to the United Nations Charter. He subsequently attended the General Assembly of the United Nations as a United States delegate in 1946, 1947 and 1950. He also published War or Peace (1950).

Dulles criticized the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman. He argued that the policy of "containment" should be replaced by a policy of "liberation". When Dwight Eisenhower became president in January, 1953, he appointed Dulles as his Secretary of State.

He spent considerable time building up NATO as part of his strategy of controlling Soviet expansion by threatening massive retaliation in event of a war. In an article written for Life Magazine Dulles defined his policy of brinkmanship: "The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art." His critics blamed him for damaging relations with communist states and contributing to the Cold War.

Dulles was also the architect of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) that was created in 1954. The treaty, signed by representatives of the United States, Australia, Britain, France, New Zealand , Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand, provided for collective action against aggression.

Dulles upset the leaders of several non-aligned countries when on 9th June, 1955, he argued in one speech that "neutrality has increasingly become an obsolete and except under very exceptional circumstances, it is an immoral and shortsighted conception."

In 1956 Dulles strongly opposed the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt (October-November). However, by 1958 he was an outspoken opponent of President Gamal Abdel Nasser and stopped him from receiving weapons from the United States. This policy backfired and enabled the Soviet Union to gain influence in the Middle East.

John Foster Dulles, suffering from cancer, was forced to resign from office in April, 1959. He died in Washington on 24th May, 1959.

On this day in 1900 Victor Silvester was born in Wembley, Middlesex. The son of a vicar he was educated at Ardingly College.

The First World War began in 1914. As he later wrote in his autobiography: "The mood of the country was one of almost hysterical patriotism, and no excuses were accepted for any man of military age who was not in uniform. Rude remarks were made about them in the streets. Sometimes they were given white feathers."

Although he was only "fourteen and nine months" he ran away to join the British Army and by the age of fifteen he was fighting on the Western Front. Silvester took part in the Battle of Arras and in 1917 he was a member of a firing squad that shot four British soldiers sentenced to death for desertion and cowardice. He later wrote: "The victim was brought out from a shed and led struggling to a chair to which he was then bound and a white handkerchief placed over his heart as our target area. He was said to have fled in the face of the enemy. Mortified by the sight of the poor wretch tugging at his bonds, twelve of us, on the order raised our rifles unsteadily. Some of the men, unable to face the ordeal, had got themselves drunk overnight. They could not have aimed straight if they tried, and, contrary to popular belief, all twelve rifles were loaded. The condemned man had also been plied with whisky during the night, but I remained sober through fear."

Victor Silvester's parents suspected he had joined the army and informed the authorities in 1914 but it was not until he was wounded in 1917 that he was discovered and brought home to England.

After the war Silvester went to Worcester College, Oxford. Later he studied music at Trinity College, London. Silvester was a talented dancer and in 1922 he won the first World Standard Ballroom Dancing Championship with Phyllis Clarke as his partner. Silvester was a founder member of the Ballroom Committee of the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing which codified the theory and practice of Ballroom Dance. In 1928 he published Modern Ballroom Dancing, which was an immediate bestseller.

In 1935 Silvester formed his own Ballroom Orchestra. His first record, You're Dancing on My Heart, was a great success. After the Second World War Silvester presented the BBC Television show Dancing Club for over 17 years.

Victor Silvester died while on holiday in France on 14th August 1978.

On this day in 1914 John Tenniel, the third son of John Baptist Tenniel (1793–1879), a dancing-master, was born in London on 28th February, 1820. His biographer, Lewis Perry Curtis, has pointed out: "Living in genteel poverty in Kensington, his parents could not afford much formal education for their six children. Tenniel, the third son, attended a local primary school and then became the pupil of his athletic father, who taught him fencing, dancing, riding, and other gentlemanly arts. At the age of twenty, while fencing with his father, the button of his opponent's foil fell off and he suffered a cut that blinded his right eye - an injury that he concealed from his father for the rest of his life in order to spare him any pangs of guilt."

Tenniel attended the Royal Academy but left in disgust at the quantity of teaching he received. When Tenniel was sixteen he began having his paintings exhibited at the Suffolk Street Galleries. He was soon recognised as a talented artist and he received several commissions, including the production of a fresco for the House of Lords.

Tenniel had some cartoons accepted by Punch Magazine and one showing Lord John Russell as David with his sword of truth attacking Cardinal Wiseman, as the Roman Catholic Goliath, upset Richard Doyle so much that he left the magazine. Mark Lemon, the editor, decided to replace Doyle with Tenniel and in December, 1850, he became a staff cartoonist with Punch. At first Tenniel was reluctant to take the post arguing that he was more concerned with "High Art". He also doubted his ability to produce humourous cartoons. He asked one friend: "Do they suppose that there is anything funny about me?"

John Tenniel gradually took over from John Leech as the producer of the main political cartoon in the magazine. Tenniel was a Tory and some of his cartoons upset radicals on the staff such as Douglas Jerrold. Tenniel denied being political prejudice and claimed that "if I have my own little politics, I keep them to myself, and profess only those of the paper".

Tenniel, who was blind in one eye, had a photographic memory and never used models or photographs when drawing. He wrote: "I have a wonderful memory of observation - not for dates, but anything I see I remember. Well, I get my subject on Wednesday night; I think it out carefully on Thursday, and make my rough sketch; on Friday morning I begin, and stick to it all day, with my nose well down on the block. By means of tracing-paper I transfer my design to the wood and draw on that. Well, the block being finished, it is handed over to Swain's boy (Joseph Swain was the engraver) at about 6.30 to 7 o'clock, who has been waiting for it for an hour or so, and at 7.30 it is put in hand for engraving. That is completed on the following night, and on Monday night I receive by post the copy of next Wednesday's paper. Although I have never the courage to open the packet. I always leave it to my sister, who opens it and hands it across to me, when I just take a glance at it, and receive my weekly pang."

Where possible, he arranged meetings with the leading politicians so that he could obtain a close look at the subjects of his drawings. On one occasion he was invited to 10 Downing Street to study the face of William Gladstone. Tenniel later claimed that Gladstone disapproved of the way he was portrayed and he was "not honoured again". Tenniel, was was a strong opponent of parliamentary reform, gave Gladstone a hard time during the debate over the 1867 Reform Act.

The Conservative Party was grateful for the support John Tenniel had given them and the Marquis of Salisbury, the Prime Minister, decided to grant him a knighthood. However, before it could be announced, the Conservatives lost power. William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, became new Prime Minister, had obviously forgiven Tenniel and agreed to let him have his knighthood.

Lewis Perry Curtis has pointed out: "Despite their dignified quality some of Tenniel's cartoons partook of the dominant prejudices of the day. His depiction of Jews included such standard antisemitic features as the hooked nose and the dark, oily locks of the Shylock–Fagin variety... Tenniel also endowed some African chieftains or warriors with such racialized traits as thick lips and big bellies. But when it came to the Irish - especially Fenians or republican separatists wedded to physical force - he delighted in simianizing rebel Paddy. Indeed, his Fenian apemen rank among the fiercest images of political violence ever to appear in the serio-comic format. By means of low foreheads, pointed ears, snub noses, high upper lips, receding chins, prognathous jaws, and sharp fangs, he turned these agitators into Calibans or gorilla–guerrillas."

M. H. Spielmann has argued: "Sir John Tenniel had dignified the political cartoon into a classic composition, and has raised the art of politico-humourous draughtsmanship into the relative position of the lampoon to that of polished satire - swaying parties and peoples, too, and challenging comparison with the higher (at times it might almost be said the highest) efforts of literature in that direction."

As well as working on Punch, Tenniel worked as a book illustrator. He is best known for the illustrations that he did for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1872). Tenniel was replaced by Bernard Partridge as chief cartoonist on the journal in 1901.

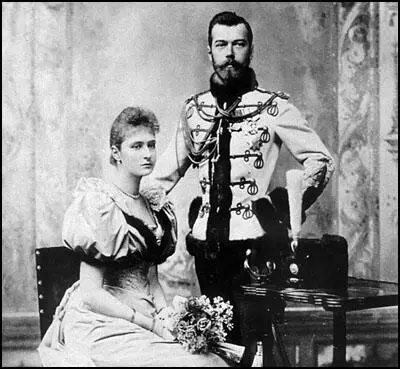

On this day in 1917 Tsarina Alexandra writes a letter to Tsar Nicholas II about the possibility of revolution. "The strikers and rioters in the city are now in a more defiant mood than ever. The disturbances are created by hoodlums. Youngsters and girls are running around shouting they have no bread; they do this just to create some excitement. If the weather were cold they would all probably be staying at home. But the thing will pass and quiet down, providing the Duma behaves. The worst of the speeches are not reported in the papers, but I think that for speaking against the dynasty there should be immediate and severe punishment."