On this day on 24th November

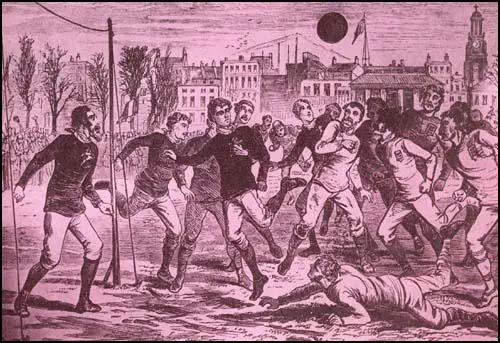

On this day in 1863 Ebenezer Cobb Morley, secretary of the Football Association, presented a draft set of 23 rules. The aim of the FA was to establish a single unifying code for football. As Percy Young, has pointed out, that the FA was a group of men from the upper echelons of British society: "Men of prejudice, seeing themselves as patricians, heirs to the doctrine of leadership and so law-givers by at least semi-divine right."

The 23 rules were based on an amalgamation of rules played by public schools, universities and football clubs. This included provision for running with the ball in the hands if a catch had been taken "on the full" or on the first bounce. Players were allowed to "hack the front of the leg" of the opponent when they were running with the ball. Two of the proposed rules caused heated debate.

IX. A player shall be entitled to run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal if he makes a fair catch, or catches the ball on the first bound; but in case of a fair catch, if he makes his mark (to take a free kick) he shall not run.

X. If any player shall run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal, any player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold, trip or hack him, or to wrest the ball from him, but no player shall be held and hacked at the same time.

Some members objected to these two rules as they considered them to be "uncivilised". Others believed that charging, hacking and tripping were important ingredients of the game. One supporter of hacking argued that without it "you will do away with the courage and pluck of the game, and it will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you with a week's practice." The main defender of hacking was F. W. Campbell, the representative from Blackheath, who considered this aspect of the game was vital in developing "masculine toughness". Campbell added that "hacking is the true football" and he resigned from the FA when the vote went against him (13-4). He later helped to form the rival Rugby Football Union. On 8th December, 1863, the FA published the Laws of Football.

1. The maximum length of the ground shall be 200 yards, the maximum breadth shall be 100 yards, the length and breadth shall be marked off with flags; and the goal shall be defined by two upright posts, eight yards apart, without any tape or bar across them.

2. A toss for goals shall take place, and the game shall be commenced by a place kick from the centre of the ground by the side losing the toss for goals; the other side shall not approach within 10 yards of the ball until it is kicked off.

3. After a goal is won, the losing side shall be entitled to kick off, and the two sides shall change goals after each goal is won.

4. A goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal-posts or over the space between the goal-posts (at whatever height), not being thrown, knocked on, or carried.

5. When the ball is in touch, the first player who touches it shall throw it from the point on the boundary line where it left the ground in a direction at right angles with the boundary line, and the ball shall not be in play until it has touched the ground.

6. When a player has kicked the ball, any one of the same side who is nearer to the opponent's goal line is out of play, and may not touch the ball himself, nor in any way whatever prevent any other player from doing so, until he is in play; but no player is out of play when the ball is kicked off from behind the goal line.

7. In case the ball goes behind the goal line, if a player on the side to whom the goal belongs first touches the ball, one of his side shall he entitled to a free kick from the goal line at the point opposite the place where the ball shall be touched. If a player of the opposite side first touches the ball, one of his side shall be entitled to a free kick at the goal only from a point 15 yards outside the goal line, opposite the place where the ball is touched, the opposing side standing within their goal line until he has had his kick.

8. If a player makes a fair catch, he shall be entitled to a free kick, providing he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once; and in order to take such kick he may go back as far as he pleases, and no player on the opposite side shall advance beyond his mark until he has kicked.

9. No player shall run with the ball.

10. Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed, and no player shall use his hands to hold or push his adversary.

11. A player shall not be allowed to throw the ball or pass it to another with his hands.

12. No player shall be allowed to take the ball from the ground with his hands under any pretence whatever while it is in play.

13. No player shall be allowed to wear projecting nails, iron plates, or gutta-percha on the soles or heels of his boots.

On this day in 1888 Helen Craggs, the daughter of Sir John Craggs, an accountant, was born in Westminster, London. She was educated at Roedean and wanted to go to university to study medicine, but her father rejected the idea. Instead, she returned to Roedean where she taught physics and chemistry.

In 1908 Helen Craggs, using the name Helen Miller, joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1908. She campaigned at the Peckham by-election for Thomas Gautrey, the Liberal Party candidate who supported women's suffrage. However, he was beaten by Henry Gooch, the Conservative Party candidate, with 60.9% of the vote.

At an election meeting in January 1908 a WSPU member had asked Winston Churchill "as a member of the Liberal government whether he will or will not give a vote to the women of this country." Churchill replied: "The only time I have voted in the House of Commons on this question, I voted in favour of women's suffrage, but having regard of the perpetual disturbance at public meetings at this election, I utterly decline to pledge myself."

Winston Churchill won the election but after his appointment as President of the Board of Trade, as the Ministers of the Crown Act required newly appointed Cabinet ministers to re-contest their seats. Helen Craggs joined other members of the WSPU, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Flora Drummond, Constance Markievicz, Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth. in the harassment of Churchill, at the Manchester North-West by-election.

Churchill lost the election by 1,241 votes. The winning Conservative Party candidate, William Joynson-Hicks, admitted: "I acknowledge the assistance I have received from those ladies who are sometimes laughed at, but who, I think, will now be feared by Mr. Churchill – the Suffragists." This press admitted that the opposition of the WSPU had largely contributed to Churchill's defeat.

The Manchester Guardian reported: "Against Mr Churchill have been arrayed not merely the regular and legitimate forces of the political party to which he is opposed, but those of a dozen outside organisations as well. Nor is it with his natural enemies alone that he has had to contend. A pledged supporter of women's suffrage, he has been persistently assailed by several women's organisations.

While in Manchester, Helen Craggs became romantically involved with Harry Pankhurst (the son of Emmeline Pankhurst). However, in April 1909, he became ill with serious inflammation of the bladder. He was cared for at a nursing home run by the suffragette Catherine Pine. According to June Purvis: "Harry told Sylvia, not their mother, that he longed to see Helen again. Soon the young woman was at Harry's bedside, telling him that she loved him too. But for the grief-stricken Emmeline, possessive of her only surviving son, the sight of the growing tenderness between the two young people was too much to bear. She chided Sylvia for acting on her own initiative. This young woman was taking from her the last precious moments with her boy." Harry died on 5 January 1910.

On 21 November 1910, David Lloyd George was making a speech at the Paragon Theatre, Whitechapel. Helen Craggs, and two friends, had broken into the theatre the previous night and climbed onto the roof "only sustained by a few pieces of chocolate they lay through the whole bitter freezing night". When Lloyd George started his speech Helen charged the platform. She was soon captured by the stewards, but "armed with a super-human strength she tore herself free". Votes for Women reported that the stewards were "absolutely appalling in its brutality. Miss Craggs was practically thrown head foremost down the stone steps."

In February 1910 Helen Craggs took over from Grace Roe as full-time organizer of the Women's Social and Political Union In Brixton on the salary of 25 shillings per month. During this period, she became close to Ethel Smyth, Evelyn Sharp and Beatrice Harraden. In March 1912 she was imprisoned in Holloway after taking part in the window-smashing campaign and went on hunger strike.

On 25th June 1912, King George V visited Wales in order to lay the foundation stone for the new National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. The Daily Telegraph reported: "While the Royal party was proceeding to the building, a woman jumped a wall and rushed towards the Home Secretary, who was in attendance, threatening vengeance for "the sufferance of the women in Holloway." The women's action really fell very flat, though doubtless she received the advertisement she desired. The only person excited by the incident was the woman herself. Everyone recognised that the object of her attack was not the King and Queen, but for Mr McKenna, and it is rather fortunate for the Suffragist that the spectators understood her purpose, for she would have run the risk of a severe handling from the crowd if she had forced her attentions on their Majesties. As it was, the woman, who is not a resident of the district, was loudly hooted. The police liberated her after an hour's detention."

It was the Daily Sketch who identified the woman as Helen Craggs: "A remarkable incident occurred as the Royal party was approaching Cathays Park. A lady, who subsequently gave her name as Helen Craggs, sprang at the Home Secretary, who was in attendance on their Majesties. She shouted at Mr McKenna that it was a shame he was going about the country where suffragists were starving in prison and had to be removed by force."

In July 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered by the conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. (13) It has speculated that this group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Mary Richardson, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks.

Helen Craggs volunteered her services and on 13th July 1912 Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody.

Helen Craggs appeared at Bullingdon Petty Sessions the next day. According to Votes for Women, "Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court." Helen pleaded guilty to the charge of "being in the garden…. For an unlawful purpose, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr Harcourt". The judge argued that because of the seriousness of the crime - eight people were asleep in the house - bail was refused.

The police suspected that the other woman was Ethel Smyth. She was arrested the next day but was released as "she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question." (18) Over fifty years later Norah Smyth confided the truth to her nephew, former diplomat Kenneth Isolani Smyth, that she was with Helen Craggs in the attempt to set fire to Harcourt's house. "He expressed surprise, knowing her love of old paintings and antiques, but Smyth explained that she knew the east wing of the house was uninhabited. It was the only violent action that she undertook as a suffragette."

At her trial it was revealed that a typewritten statement was found in her handbag: "Sir, it is with a deep sense of my responsibility and a sincere conviction that my action is justifiable that I have taken a serious step in the cause of women's enfranchisement… I deplore that though during the past six years the demand for political liberty for women has become the greatest agitation of the time, politicians were content to see the supporters violently treated and unjustly imprisoned rather than give them the long-delayed and much-needed measure of justice which they demanded."

It was claimed that the women were carrying a basket and a satchel. These contained "a bottle and two cans, which contained nearly three pounds of inflammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, nine picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter, and thirteen keys."

Helen Craggs was sentenced to serve nine months with hard labour in Holloway. She went on hunger strike and was force-fed five times over two days. Her health was extremely bad and she was released after eleven days, suffering from internal and external bruising. In 1913 she went to Dublin to train as a midwife and a year later married Dr Alexander McCombie, who was working in the East End of London.

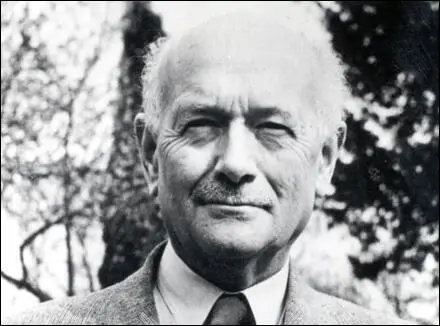

On this day in 1890 Ernest Bader, the youngest of thirteen children, was born in Regensdorf, Switzerland. He was expelled from school at the age of twelve and went to work in a Zürich chemical factory.

Bader studied commerce and languages at night school and at the age of 21 found work in an office. Bader emigrated to England in 1912, and found employment as a clerk for a silk merchant. Bader became involved in politics and under the influence of Reginald Sorensen, a Unitarian minister, he became a pacifist and a Christian Socialist.

On the outbreak of the First World War he became a conscientious objector and between 1917 and 1920 worked on a smallholding adjoining Sorensen's farming community of conscientious objectors at Stanford-le-Hope. During the war Bader married Dora Scott and later adopted three war orphans of different nationalities and backgrounds, before the births of their own children.

According to his biographer, John G. Corina: "In 1920 Bader deployed his wife's capital of £300 to start a London-based import agency for celluloid. This operation expanded into a specialist chemical manufacturing company, Scott Bader Ltd, making new products and synthetic resin... Bader combined marketing energy and individualistic leadership with a flair for spotting and applying new technology, and the company eventually became the leading innovator in plastics technology, in an industry generally dominated by capital-intensive giants."

The Scott Bader Company was based in Wollaston, Northamptonshire. Bader was a paternalistic employer and his loyal, non-unionized workforce helped him to develop a company that was worth over £2 million. As Andrew Rigby has pointed out: "Although successful as judged by normal capitalist standards Bader... remained dissatisfied with the disjunction between Christian morality and the ethics of competitive capitalism in general... This led him to think seriously about turning his company into some form of cooperative fellowship."

Bader became friends with John Middleton Murry who argued for "socialist-communities, prepared for hardship and practised in brotherhood, might be the nucleus of a new Christian Society, much as the monasteries were during the dark ages." He purchased a farm in Langham, Essex and established a pacifist community centre they called Adelphi Centre on the land. Murry argued he was attempting to create "a community for the study and practice of the new socialism".

In 1945 Bader joined the Society of Friends. His political and religious views influenced his views as a businessman. As John G. Corina has pointed out: " Fired with post-war reconstruction ardour, workplace benevolence was not enough for him. He saw that authoritarian managements were less productive than participative systems, and that human dignity in the workplace and mutual service were industrial values that transcended the hierarchical work concepts promoted by private greed or remote nationalization. A wave of imitative experiments might, he conjectured, eventually implant self-government across industry, encouraging private manufacturers and state enterprise boards to devolve power gradually to employees, to share surpluses, rights, and duties, and to shoulder ethical responsibilities."

Bader became friendly with Wilfred Wellock. As a young man he had been a supporter of Guild Socialism, a movement that advocated workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds. The author of A Life in Peace: A Biography of Wilfred Wellock (1988) argued: "Bader had been in correspondence with Wellock concerning his ideas and quoted from him in the conclusion to the document. But the whole tenor of the proposal displayed strong echoes of Wellock's ideas. He stressed the desirability of limiting the size of enterprises, emphasised the social responsibility of industry, referred to the human potential for cooperative effort, and affirmed the crucial importance of worthwhile work for the development of the individual."

In 1951 Ernest Bader finally formed the Scott Bader Commonwealth and handed over 90% of the shares held by the Bader family to a newly constituted body, the Commonwealth, made up of all those members of the workforce. Bader remained managing director of this highly successful company until his son, Godric, took over in 1957.

In 1957 Bader joined forces with Kingsley Martin, Canon John Collins, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Wilfred Wellock, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, E. P. Thompson, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, Stuart Hall, Ralph Miliband, Frank Cousins, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to establish the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Bader joined forces with Wilfred Wellock and Canon John Collins in 1958 to establish Demintry (Society for Democratic Integration in Industry). The main objective of the organisation was to develop: "An ideological development of industry into living communities and basic democracies, where the company is chartered and constituted as a form of common ownership of the means of production. Its purpose is to create ideals which turn men into servers, rather than that ideals should merely serve man."

In 1963 the remaining 10% of the shares of Scott Bader was handed over to the Commonwealth. Ernest Bader argued: "What the worker really dreams of is the acquiring of social function and status ... Increases in wages or better conditions of work can be no moral equivalent for pride in craftmanship, social recognition and acclaim, opportunities for advancement and for the free expression of personality and initiative."

Ernest Bader died at his home in Wollaston on 5th February 1982. According to John G. Corina "he owned no private house, car, or personal business assets, nor had he made capital transfers or gifts before his death."

On this day in 1911 Henry Nevinson publishes an article in Votes for Women about the arrest of May Billinghurst. "Going to Cannon Row between 9.30 and 10.00 I found arrested women being brought in there every few minutes. The numbers in that station alone had reached 180 by 9.50. Just at that time as I was returning to Whitehall I met Miss Billinghurst, that indomitable cripple, being carried shoulder high by four policemen in her little tricycle or wheel-cart that she propels with her arms. Amid immense cheering from the crowd she followed the rest into the police station."

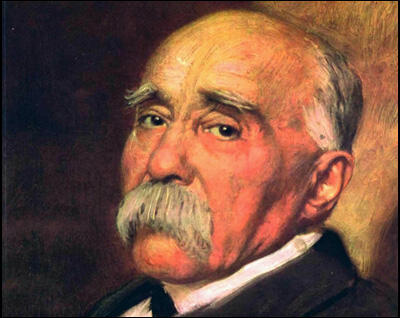

On this day in 1929 Georges Clemenceau died in Paris. In November 1917 the French president, Raymond Poincare appointed Clemenceau as prime minister. He immediately clamped down on dissent and senior politicians calling for peace, such as Joseph Caillaux and Louis Malvy were arrested for treason. In a speech on 20th November 1917 Clemenceau said: "We promise you, we promise the country, that justice will be done according to the law. Weakness would be complicity. We will avoid weakness, as we will avoid violence. All the guilty before courts-martial. The soldier in the courtroom united with the soldier in battle. No more pacifist campaigns, no more German intrigues. Neither treason, nor semi-treason: the war. Nothing but the war. Our armies will not be caught between fire from two sides. Justice will be done. The country will know that it is defended."

Clemenceau, who also became minister of war in the government, and played an important role in persuading the British to accept the appointment of Ferdinand Foch as supreme Allied commander. He also insisted that the exhausted French Army led the offensive against the German Army in the summer of 1918.

At the Versailles Peace Conference Clemenceau clashed with Woodrow Wilson and David Lloyd George about how the defeated powers should be treated. Lloyd George told Clemenceau that his proposals were too harsh and would "plunge Germany and the greater part of Europe into Bolshevism." Clemenceau replied that Lloyd George's alternative proposals would lead to Bolshevism in France. At the end of the negotiations Clemenceau managed to restore Alsace-Lorraine to France but some of his other demands were resisted by the other delegates. Clemenceau, like most people in France, thought that Germany had been treated too leniently at Versailles. Clemenceau's failure to achieve all his demands resulted in him being rejected by the French electorate in January 1920.

On this day in 1949 Sally Davies was born. Davies became Chief Medical Officer for England on 1st June 2010. All modern countries run pandemic exercises every few years. In most countries they take these pandemic exercises very seriously and follow the recommendations of the scientists who write the report on what has taken place. In October 2016, the UK government ran a national pandemic flu exercise, codenamed Exercise Cygnus. The report of its findings was not made publicly available, but the then chief medical officer Sally Davies commented on what she had learnt from it at a conference in December 2016. "We've just had in the UK a three-day exercise on flu, on a pandemic that killed a lot of people," she told the World Innovation Summit for Health. "It became clear that we could not cope with the excess bodies," Davies said. One conclusion was that Britain, as Davies put it, faced the threat of "inadequate ventilation" in a future pandemic. She was of course referring to the fact that compared to other advanced nations, the UK was desperately short of ventilation machines. Jeremy Hunt, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, decided to classify the report because the government was not willing to release the money needed to pay for the report's recommendations. Sally Davies resigned in disgust and gave up her £215,000 salary and took up an academic post at Trinity College, Cambridge. Her replacement, Chris Whitty, was someone who is unprincipled enough to pretend he agrees with the decisions of Boris Johnson during the Covid Pandemic.

On this day in 1958 Robert Cecil, Viscount of Chelwood, died. Cecil, the third son of the Marquis of Salisbury, was born on 14th September, 1864. Educated at Eton and Oxford University, he was called to the Bar in 1887. A member of the Conservative Party, he was elected to the House of Commons in 1906. On the left of the party, Cecil was one of the few Conservatives who supported women's suffrage.

On the outbreak of the First World War Cecil went to work for the Red Cross. He was recalled in 1915 to serve in the government as under secretary for foreign affairs. The following year he was given responsibility for devising procedures to bring economic and commercial pressure against the enemy. In 1918 David Lloyd George appointed him as assistant secretary of state for foreign affairs.

Cecil's experiences during the war convinced him that civilization could survive only if it could develop an international system that would insure peace. In September 1916 he wrote a memorandum that advocated the formation of an international body that he called the League of Nations.

When peace negotiations began in October, 1918, Woodrow Wilson insisted that his Fourteen Points should serve as a basis for the signing of the Armistice. This included the formation of the League of Nations. Cecil was appointed as the British representative in charge of negotiations for this new organization.

The constitution of the League of Nations was adopted by the Paris Peace Conference in April, 1919. The League's headquarters were in Geneva and its first secretary-general was Sir Eric Drummond. The Covenant (Constitution) of the League of Nations called for collective security and the peaceful settlement of disputes by arbitration. It was decided that any country that resorted to war would be subjected to economic sanctions.

The main organs of the League of Nations were the General Assembly, the Council and the Secretariat. The General Assembly, which met once a year, consisted of representatives of all the member states and decided on the organization's policy. The Council included four permanent members (Britain, France, Italy and Japan) and four (later nine) others elected by the General Assembly every three years. The Secretariat prepared the agenda and published reports of meetings.

Cecil represented the Dominion of South Africa in the League Assembly. He was also president of the British League of Nations Union (1923-1945) and a leader of the International Peace Campaign. In 1923 Cecil was granted the title Viscount of Chelwood. As a member of the House of Lords he remained in the government as Lord Privy Seal (1923-1924) and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1924-1927). However he resigned from the government in 1927 because of its lack of support for the League of Nations.

Cecil, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1937, wrote several books on international affairs including The Way of Peace (1928) and the Great Experiment (1941). He was present at the final meeting of the League of Nations and ended his speech with the words: "The League is dead, long live the United Nations." Cecil's autobiography, All the Way, was published in 1949. He remained active in the House of Lords until his death on 24th November, 1958.

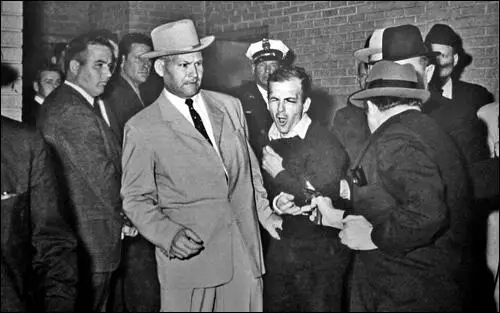

On this day in 1963 Lee Harvey Oswald was murdered . After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy Oswald was interrogated by the Dallas Police for over 13 hours. However, the police made no tapes nor took any transcripts of the interrogations. Oswald denied he had been involved in the killing of Kennedy. He also told newsmen that he was a "patsy" (a term used by the Mafia to describe someone set up to take the punishment for a crime they did not commit).

On 24th November, 1963, Jesse Curry decided to transfer Oswald to the county jail. Will Fritz placed George Butler in immediate charge of the transfer. Ike Pappas, a journalist working for WNEW Radio in Maryland was one of the hundred people watching Oswald being led through the basement of police headquarters. “I noted out of the corner of my eye, this black streak went right across my front and leaned in and, pop, there was an explosion. And I felt the impact of the air from the explosion of the gun on my body.... And then I said to myself, if you never say anything ever again into a microphone, you must say it now. This is history.”

The gunman was quickly arrested by police officers. Oswald died soon afterwards. The man who killed him was later identified as being Jack Ruby. This was surprising as he was not a Kennedy supporter and during the summer of 1963 he had been in contact with Mafia leaders, Carlos Marcello and Santos Trafficante, during the summer of 1963.

Nancy Perrin Rich worked for Ruby at his Carousal Club. She told the Warren Commission that Ruby had instructed her to supply free drinks to the Dallas Police Department. Rich added "I don't think there is a cop in Dallas that doesn't know Jack Ruby. He practically lived at that (police) station. They lived in his place."

Ruby told Earl Warren that he would "come clean" if he was moved from Dallas and allowed to testify in Washington. He told Warren "my life is in danger here". He added: "I want to tell the truth, and I can't tell it here." Warren refused to have Ruby moved and so he refused to tell what he knew about the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

The journalist Dorothy Kilgallen had a source within the Warren Commission. This person gave her an 102 page segment dealing with Jack Ruby before it was published. She published details of this leak and so therefore ensuring that this section appeared in the final version of the report. The Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated the leak and on 30th September, 1964, Kilgallen reported in the New York Journal American that the FBI "might have been more profitably employed in probing the facts of the case rather than how I got them".

Kilgallen's reporting brought her into contact with Mark Lane who had himself received an amazing story from the journalist Thayer Waldo. He had discovered that Jack Ruby, J. D. Tippet and Bernard Weismann had a meeting at the Carousel Club eight days before the assassination. Waldo, who worked for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, was too scared to publish the story. He had other information about the assassination. However, he believed that if he told Lane or Kilgallen he would be killed. Kilgallen's article on the Tippit, Ruby and Weissman meeting appeared on the front page of the Journal American. Later she was to reveal that the Warren Commission were also tipped off about this gathering. However, their informant added that there was a fourth man at the meeting, an important figure in the Texas oil industry.

During his trial Ruby claimed he had killed Lee Harvey Oswald because he "couldn't bear the idea of the President's widow being subjected to testifying at the trial of Oswald". Later he changed his mind claiming that his lawyer, Tom Howard, had put him up to saying it. He now pleaded guilty by reason of insanity. On March 14, 1964, the jury convicted Jack Ruby of killing Oswald and sentenced him to death.

In October, 1964, the Warren Commission reported that it "found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy". It also stated that there was no "significant link between Ruby and organized crime". This information came from friends of Ruby, including Dave Yarras, a Mafia hit man.

Kilgallen was keen to interview Jack Ruby. She went to see Ruby's lawyer Joe Tonahill and claimed she had a message for his client from a mutual friend. It was only after this message was delivered that Ruby agreed to be interviewed by Kilgallen. Tonahill remembers that the mutual friend was from San Francisco and that he was involved in the music industry. Kennedy researcher, Greg Parker, has suggested that the man was Mike Shore, co-founder of Reprise Records.

The interview with Ruby lasted eight minutes. No one else was there. Even the guards agreed to wait outside. Officially, Kilgallen never told anyone about what Ruby said to her during this interview. Nor did she publish any information she obtained from the interview. There is a reason for this. Kilgallen was in financial difficulties in 1964. This was partly due to some poor business decisions made by her husband, Richard Kollmar. The couple had also lost the lucrative contract for their radio show Breakfast with Dorothy and Dick. Kilgallen also was facing an expensive libel case concerning an article she wrote about Elaine Shepard. Her financial situation was so bad she fully expected to lose her beloved house in New York City.

Kilgallen was a staff member of Journal American. Any article about the Jack Ruby interview in her newspaper would not have helped her serious financial situation. Therefore she decided to include what she knew about the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Murder One. She fully expected that this book would earn her a fortune. This is why she refused to tell anyone, including Mark Lane, about what Ruby told her in the interview arranged by Tonahill. In October, 1965, told Lane that she had a new important informant in New Orleans.

Kilgallen began to tell friends that she was close to discovering who assassinated Kennedy. According to David Welsh of Ramparts Magazine Kilgallen "vowed she would 'crack this case.' And another New York show biz friend said Dorothy told him in the last days of her life: "In five more days I'm going to bust this case wide open." Aware of what had happened to two other journalists working on the case: Bill Hunter (murdered on 23rd April 1964) and Jim Koethe, (murdered 21st September, 1964), Kilgallen handed a draft copy of her chapter on the assassination to her friend, Florence Smith.

On 8th November, 1965, Kilgallen, was found dead in her New York apartment. She was fully dressed and sitting upright in her bed. The police reported that she had died from taking a cocktail of alcohol and barbiturates. The notes for the chapter she was writing on the case had disappeared. Her friend, Florence Smith, died two days later. The copy of Kilgallen's article were never found.

Jack Ruby's original conviction was later overturned, but he died from cancer on 3rd January, 1967, while waiting for a new trial.