On this day on 18th March

On this day in 1745 Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, died. Robert Walpole was born in Houghton Hall on 26th August 1676. Educated at Eton and King's College, Cambridge, he intended to enter the Church but changed his mind and became active in politics instead.

Walpole, a Whig, was elected to the House of Commons in 1701. An outstanding orator, Walpole was appointed Secretary of War in 1708 and Treasurer of the Navy in 1710. After the collapse of the Whig government Walpole was accused of corruption and spent a short period in the Tower of London.

In 1714 Queen Anne became very ill. The true heir to the throne was James Stuart, the son of James II. Many Tory ministers supported James becoming king. However, James Stuart was a Catholic and was strongly opposed by the Whigs. A group of Whigs visited Anne just before she died and persuaded her to sack her Tory ministers. With the support of the Whigs, Queen Anne nominated Prince George of Hanover as the next king of Britain.

When George arrived in England, he knew little about British politics nor could he speak very much English. George therefore became very dependent on the Whigs who had arranged for him to become king. This included Walpole who was made Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1715.

Walpole was such a powerful figure in the government he became known as Prime Minister, the first in Britain's history. He was also given 10 Downing Street by Prince George, which became the permanent home of all future Prime Ministers.

Walpole believed that the strength of a country depended on its wealth. The main objective of Walpole's policies was to achieve and maintain this wealth. For example, he helped the business community sell goods by removing taxes on foreign exports.

Robert Walpole did all he could to avoid war, as he believed it drained a country of its financial resources. However, in 1739 Britain became involved in a war with Spain. George II was in favour of the war and became Britain's last king to lead his troops into battle. Walpole, who thought the war was unnecessary, did not provide the dynamic leadership needed during a war. The Tory opposition accused Walpole of not supplying enough money for the British armed forces. Walpole gradually lost the support of the House of Commons, and in February 1742 he was forced to resign from office.

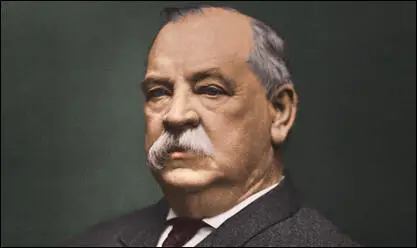

On this day in 1837 President Grover Cleveland, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was born in Caldwell, New Jersey, on 18th March, 1837. After the death of his father he had to support his widowed mother and decided not to go to college. He worked for a law firm in Buffalo and after becoming a member of the Democratic Party, was elected mayor of the town.

Cleveland's reputation for being an honest politician helped him become governor of New York in 1882. Two years later Cleveland was selected as the Democratic Party presidential candidate. In the election Cleveland was helped by the strong showing of John St. John, the candidate of the Prohibition Party. His votes were mainly taken from James Blaine of the Republican Party. Cleveland won and became the first Democrat to be elected president since the Civil War.

Cleveland was a reforming president and attempted to deal with patronage by transferring jobs to the civil service. However, attempts to reduce high protective tariffs was blocked by the Republican controlled Senate.

The tariff issue dominated the 1888 presidential election and contributed to him being defeated by the Republican candidate, Benjamin Harrison. Cleveland returned to his law practice in New York until being nominated to be the Democratic candidate in the 1892 presidential election. This time Cleveland defeated Harrison and he became president for a second time.

Grover Cleveland was concerned with the drain of gold from the Treasury. In 1894 and 1895 he issued bonds to obtain gold, selling them to a banking syndicate headed by J. P. Morgan. This was unpopular with the rural community and he also lost support from the emerging labour movement, when he sent troops to deal with a railroad strike in Chicago.

In foreign policy Cleveland was an isolationist. However, he implied that the United States would be willing to go to war during a dispute with Britain over the Venezuela-British Guiana boundary. Richard Olney, his secretary of state, managed to persuade the British government to accept arbitration and war was avoided. After Cleveland's retirement from politics in 1897, he became a lecturer at Princeton University.

Grover Cleveland died on 24th June, 1908.

On this day in 1867 Benjamin Disraeli makes speech in favour of parliamentary reform. William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that he was also in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, Lord Derby's new government were now sympathetic to the idea. The Conservatives knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Disraeli "feared that merely negative and confrontational responses to the new forces in the political nation would drive them into the arms of the Liberals and promote further radicalism" and decided that the Conservative Party had to change its policy on parliamentary reform.

Benjamin Disraeli argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, (later 3rd Marquess of Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy."

On 21st March, 1867, William Gladstone made a two hour speech in the House of Commons, exposing in detail the inconsistencies of the bill. On 11th April Gladstone proposed an amendment which would allow a tenant to vote whether or not he paid his own rates. Forty-three members of his own party voted with the Conservatives and the amendment was defeated. Gladstone was so angry that apparently he contemplated retirement to the backbenches.

However, Disraeli did accept an amendment from Grosvenor Hodgkinson, which added nearly half a million voters to the electoral rolls, therefore doubling the effect of the bill. Gladstone commented: "Never have I undergone a stronger emotion of surprise than when, as I was entering the House, our Whip met me and stated that Disraeli was about to support Hodgkinson's motion."

On 20th May 1867, John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, and the leading male supporter in favour of women's suffrage, proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Gladstone voted against the amendment.

Other amendments were accepted: Out went the "dual vote" which allowed people with property to vote in town and country. The clause that would give extra votes for people with savings or education. So did the requirement that ratepayers would need to show two years' residence - the condition was reduced to one year. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, complained that "all the precautions, guarantees, and securities in the Bill" had disappeared. He told Disraeli: "You are afraid of the pot boiling over. At the first threat of battle you throw your standard in the mud".

Benjamin Disraeli dismissed these points by right-wing members of his party, by claiming that this reform will guarantee peace in the years to come: "England is safe in the race of men who inhabit her, safe in something much more precious than her accumulated capital - her accumulated experience. She is safe in her national character, in her fame and in that glorious future which I believe awaits her."

William Gladstone decided not to take part in the debate on the third reading of the bill as he feared it would have a negative reaction: "A remarkable night. Determined at the last moment not to take part in the debate: for fear of doing mischief on our own side." Without provocation from Gladstone the bill was passed without division. The House of Lords also agreed to pass the 1867 Reform Act.

The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832.

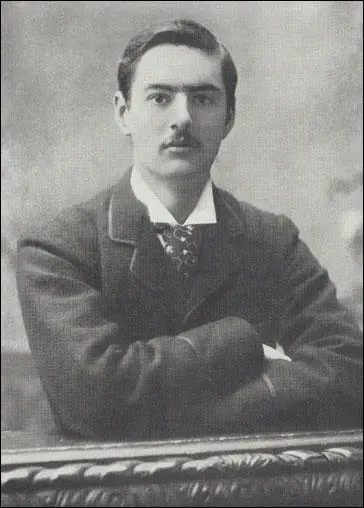

On this day in 1869 Neville Chamberlain, the only son of Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) and his second wife Florence Kenrick (1847–1875) on 18th March, 1869 at Edgbaston, Birmingham. His father's first wife, Harriet Kenrick, had died while giving birth to Neville's elder half-brother, Austen Chamberlain, in 1863, and he married her cousin, in 1868.

Chamberlain grew up in an atmosphere of fervent Unitarianism, within a happy family surrounded by cousins. However, his mother died in 1875 after the birth of her fourth child. "This unquestionably left its mark on Joseph Chamberlain and imposed a certain strain on his relations with his children."

Joseph had two children by his first wife: Beatrice and Austin and four children by his second wife: Neville, Ida, Hilda and Ethel. Joseph became mayor of Birmingham in 1873 and the following year he sold the family business for £120,000. He invested heavily in South America and lived off the interest. A member of the Liberal Party he was elected to the House of Commons to represent Birmingham on 17th June, 1876.

Neville Chamberlain hated his time at Rugby School where he was badly bullied by a boy whom Austen had beaten when he was a school prefect. As a result he became somewhat shy and withdrawn and was a reluctant participant in school debates. When asked why this was he referred to the unpleasant atmosphere in the house when his father was preparing to make an important speech. It has been suggested that this probably reflected his "adolescent resentment against a dominant father".

At the end of 1886 Neville left school, but there was no question of his following Austen to Cambridge University. Austen had been sent there by his father and thence on an extensive tour of Europe as preparation for a career in politics. Joseph Chamberlain admitted that Neville was "the really clever one" but thought it would be better to send him to study metallurgy and engineering at Mason Science College.

Andrew J. Crozier pointed out: "Although but a university education was deemed an unnecessary expense for a career in business. In this Joseph Chamberlain, although unintentionally, did Neville a great disservice. A university education would in all probability have made him a better integrated, more self-confident, and poised personality, with a capacity to project his inner warmth beyond the confines of the family and intimate friends and an ability to appreciate that there were points of view as intellectually sound as his own."

In 1890 there was a massive slump in the Argentinean economy, which threatened the Chamberlain family with financial meltdown. Joseph Chamberlain, who at that time was the Colonial Secretary, had a conversation with Ambrose Shea, the Governor of the Bahamas, persuaded him that he could recoup his losses by growing sisal, a plant with stiff purple leaves from which high-quality hemp could be made. Joseph sent Neville to Nassau to investigate the prospect of what promised to be a 30 per cent return on his investment.

In May 1891, Neville Chamberlain was given the responsibility of setting up the venture on the remote Bahamian island of Andros. The following month he was able to write: "It is with the deepest satisfaction that I am able to inform you today that the first part of my business is satisfactorily concluded. I have pitched on a tract of land in Andros Island and made an agreement with the governor... on the whole it is of excellent quality, very level, and unbroken... I am confident that I have secured the best site available in the Bahamas."

It was a lonely existence.with his nearest neighbour, was only three miles away but it was a difficult journey that would take up most of the day. Knowles, his white overseer was poorly educated and was not a good "mental companion". He did enjoy talking to his wife but she died and he wrote: "What little social life I had is gone absolutely, and I see myself condemned to a life of total solitude, mentally if not physically." He therefore had to depend on a chance visit from a passing sponge merchant, or the mission priest from Fresh Creek, twenty miles to the south. His main excitement was the letters he received every fortnight.

Joseph Chamberlain encouraged his son to stay on this remote island: "I feel that this experience, whatever its ultimate result on our fortunes, will have had a beneficial and formative effect on your character. At times, in spite of all the hardships and annoyances you have to bear, I am inclined to envy you the opportunity you are having to show your manhood. Remember, however, now and always that I value your health more than anything, and that you must not run any unnecessary risks either by land or sea."

Neville Chamberlain's initial optimism was misplaced. Sisal plants did not grow successfully on the island and warned his father that the venture might fail. His father replied that "you seem to contemplate as a possibility the entire abandonment of the undertaking in which I shall have invested altogether (with the liabilities I have accepted) about £50,000. This would indeed be a catastrophe."

In April 1896, after five years of hard toil Neville accepted defeat: "I no longer see any chance of making the investment pay. I cannot blame myself too much for my want of judgment. You and Austen have had to rely solely on my reports but I have been here all the time and no doubt a sharper man would have seen long ago what the ultimate result was likely to be... I should be much more than willing to spend another ten years here, if by so doing I could make a success out of the business in which I have failed."

Chamberlain arrived back in England in 1897. Two wealthy uncles, both prominent Midlands industrialists, arranged for him to be appointed director of Elliott's Metals Company. Family connections enabled him to be appointed to the board of the Birmingham Small Arms Company. He also took control of Hoskins & Sons, manufacturers of ships berths. "It was Hoskins' that he gave most of his time, and he found a deep satisfaction in proving that on his own he could survive."

Neville Chamberlain was considered to be a good employer. "He was accessible to his workers and solicitous of their welfare to the extent of encouraging trade union membership, in which he was considerably in advance of his contemporaries. At Elliott's, Chamberlain introduced a surgery and welfare supervisors... At Hoskins he was equally innovative in welfare and reform, devising a 5 per cent bonus on production and a pension plan. When business was slack he was reluctant to lay men off. Indeed, for his time he was an exemplary employer and could justifiably take pride in the fact that he never experienced a strike."

In 1911, aged 41, Neville Chamberlain married Anne Cole de Vere (1882-1967), after a brief courtship. It was described as a strange relationship, "he precise and meticulous, she impulsive and emotionally volatile" and yet their marriage was a long and happy one. After their marriage the couple moved to Westbourne, Edgbaston, which was to be their home for the remainder of their lives. Later that year she bore him a daughter, Dorothy and in 1913 a son named Frank.

Chamberlain began to take an interest in politics. His father had left the Liberal Party over the issue of Irish Home Rule, and his small group of so-called Liberal Unionists and subsequently allied themselves to the Conservative Party. His brother, Austen Chamberlain, followed the same route and was MP for East Worcestershire. In 1911, Neville Chamberlain successfully stood as a Liberal Unionist for Birmingham City Council for the All Saints' Ward, located within his father's parliamentary constituency. During the campaign he stressed the need for town planning and open spaces. He also argued for the extension of the canal system.

Within three years he became an alderman, and the following year he became Lord Mayor. Chamberlain held very progressive views and it was said that he acted like a member of the Labour Party. In fact, "several times he voted with his party opponents against deferment of an increase in teachers' salaries or a delay in extending technical schools." He also got the support of the Labour members in his dealing with the problems of health, housing and town planning. As he pointed out, the death-rate was 24 per thousand in working-class areas but only 9 in the suburbs.

Chamberlain had genuine concern for the lives of working-class people. After reading The Town Labourer: 1760-1832 by Barbara Hammond and John Lawrence Hammond Chamberlain wrote in his diary: "It is extraordinarily interesting and, being written avowedly from the point of view of the labourer, so excites one's sympathy that one feels rebellion would have been more than justified over and over again in the face of such gross injustice and such brutal and inhuman oppression."

Chamberlain explained the problems that Birmingham faced: "A large proportion of the poor in Birmingham are living under conditions of housing detrimental both to their health and morals" and the landlords were blind to "their moral obligations" and the tenants indifferent "to the laws of God or man". He urged the building of new estates in the surrounding countryside where life could "be made better with air and gardens" and "where town planning could prevent the making of new slums". Hopefully, these houses for the working-classes could be built by private companies but in "the last resort, if private enterprise failed, the corporation must step in". Chamberlain spoke of the need to move "the working classes from their hideous and depressing surroundings to cleaner, brighter and more wholesome dwellings in the still uncontaminated country which lay within the city's boundaries".

Chamberlain's achievements in Birmingham came to the attention of David Lloyd George, the Minister of Munitions. During the First World War the country had a major problem in producing enough weapons and ammunition to defeat Germany. In June 1915, Lloyd George invited Chamberlain to serve on the liquor control board, set up to minimize the impact of alcohol consumption on arms production. He wrote in his diary: "I have been appointed a member of the Central Control Board to control liquor in munitions and transport areas. It is but one aspect of the great labour problem. The frantic competition among employers for labour has led to extravagant wages, relaxation of discipline, and bad timekeeping."

In a letter he wrote to his mother he expressed his thoughts on the relationship between the workers and the employers: "I feel that National Service is the only solution of the present situation, which is rapidly becoming intolerable. It must, however, be accompanied by either a surtax on, or a limitation of profits for all, because workmen will never consent to restrictions which would have the effect of putting money into their employers' pockets. Personally I hate the idea of making profits out of the war when so many are giving their lives and limbs, and I hope and pray that the new government will have the courage and the imagination to deal with the situation promptly and properly."

In 1916 Chamberlain was appointed Director of National Service. The scheme involved securing the voluntary recruitment of men and women for essential war work. Over the next seven months Chamberlain was constantly obstructed by the War Ministry, the Minister of Labour and the Unemployment Exchanges in his efforts to secure the transfer of industrial workers. "So complete was the failure that by the time of Chamberlain's resignation (in August 1917) just 3,000 volunteers for essential war work had been placed in employment."

Neville Chamberlain thought that this disaster would have a long-term impact on his political career. He wrote in his diary: "My career is broken. How can a man of nearly 50, entering the House with this stigma upon him, hope to achieve anything? The fate I foresee is that after mooning about for a year or two I shall find myself making no progress... I shall perhaps be defeated in an election, or else shall retire, and that will be the end. I would not attempt to re-enter public life if it were not war-time. But I can't be satisfied with a purely selfish attention to business for the rest of my life."

Chamberlain could now concentrate on local matters and established the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He felt that a city of Birmingham's stature should be endowed with an orchestra of a high standard and that it should be funded partly from the rates. "There was, though, an additional agenda: such an orchestra, located in a large concert hall, would, through cheaper seats, make music both accessible to a wider audience and simultaneously more self-financing. In 1919 an annual grant from the rates was voted and made possible the creation of the city orchestra."

During the war the government sought to persuade its reluctant citizens to invest their wages in war loans. Chamberlain believed that this could be achieved through municipal savings associations, which would encourage people to save (their contribution being deducted from their wages at source) but which, in return for guaranteed interest, forbade them from withdrawing their savings until the end of hostilities, released this money for use as a war loan. The Birmingham Municipal Bank was established in 1916 and was made permanent by an act of parliament in 1919 with the additional power to advance mortgages to depositors.

Neville Chamberlain was devastated by the death of his cousin, Norman Chamberlain, aged 27, in December, 1917, while fighting on the Western Front. He served with Norman on the city council and claimed he was "the most intimate friend I had." After leaving university Norman had dedicated his life to helping "boys who were victims of our urban civilisation". At his "own cost had emigrated many to Canada, crossed the sea to visit them". Neville wrote in his diary: "Somehow I had always associated Norman with anything I might do in the future. He was like a younger brother to me." "His life was devoted to others, and I feel a despicable thing beside him."

On this day in 1901 Esther Roper, the leader of the Lancashire and Cheshire Women's Textile and Other Workers Representation Committee, presents a petition signed by 29,359 women textile workers to Parliament demanding women's suffrage. Esther also co-edited the Women's Labour News, a quarterly journal aimed at uniting women workers. She was also active in the socialist group, the Independent Labour Party.

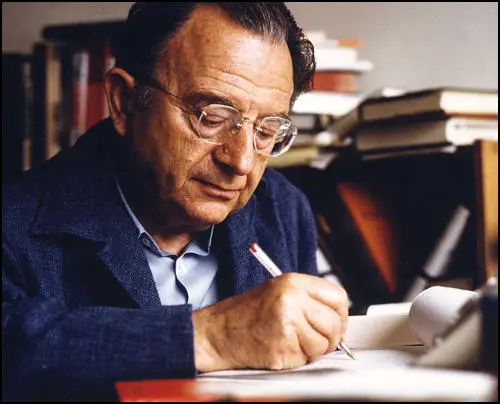

On this day in 1980 philosopher Erich Fromm died. Fromm, the son of Rosa Krause Fromm and Naphtali Fromm, was born in Frankfurt, Germany on 23rd March, 1900. Both his parents were orthodox Jews. Erich was the couple's only child. It was not a happy marriage and he later described his father as distant and his mother as overprotective.

Fromm's great-uncle, Ludwig Krause, was a prominent Talmudic scholar and a great influence on his life. "Erich became fascinated with the Hebrew Bible, especially with the prophetic writings of Isiah, Amos, and Hosea and their visions of peace and harmony among nations."

For a long time Erich Fromm hoped to make the study of the Talmud his life's work. However, "for Fromm, the main point was, perhaps, not what he studied, but rather the values attached to studying and the different way of life that marks it out." Fromm was given an intense religious education from noted scholars and friends of the family, and groomed from an early age to carry on family tradition and became a scholar of the Talmud."

In 1912 Naphtali Fromm employed Oswald Sussman, a young Galacian Jew, to help him with his wine business. Sussman lived in the Fromm household for two years and during this period he took an interest in Erich's education. This included visits to Frankfurt Museum. Sussman was a socialist and introduced him to the writings of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels and engaged him in serious discussions about politics. Fromm later recalled that Sussman "was an extremely honest man, courageous, a man of great integrity. I owe a great deal to him."

Fromm adopted Sussman as a father figure. He later claimed that Sussman was the first adult to take a real interest in him as an individual. Fromm did not enjoy a good relationship with his father who he believed was "very neurotic" and "obsessive". Fromm claimed that he "suffered under the influence of a pathologically anxious father who overwhelmed me with his anxiety, at the same time not giving me any guidelines and having no positive influence on my education."

Erich was 14-years-old and a student at Frankfurt's Wohler Gymnasium, when the First World War broke out. His Latin teacher, who had previously argued that the German arms build-up would keep the peace was jubilant: "From then on, I found it difficult to believe in the principle that armament preserved peace." Fromm was shocked by how overnight his teachers and fellow students became "fanatical nationalists and reactionaries" attributing the war to British aggression. Only his English teacher proclaimed a different message and warned against a quick military victory pointing out that "so far England has never lost a war." Erich Fromm described the war as "the most crucial experience in my life." Following the example of his English teacher, he came to resist the simplistic portrayal of an innocent Germany being attacked by a bellicose Britain. Some of his uncles and cousins were killed during the war. Some of his uncles and cousins were killed during the war. Oswald Sussman also lost his life in the conflict. "When the war ended in 1918, I was a deeply troubled young man who was obsessed by the question of how war was possible, by the wish to understand the irrationality of human mass behavior, by a passionate desire for peace and international understanding."

In 1918 Fromm attended the University of Frankfurt am Main where he took courses in medieval German history, the theory of Marxism, social movements, and the history of psychology. Fromm also came under the influence of the writings of Hermann Cohen, the celebrated neo-Kantian philosopher and biblical scholar, who was a liberal in terms of religious observance and biblical exegesis but espoused a variety of socialist humanism similar to that of Moses Hess, the left-wing Hegelian who had converted Frederick Engels, and Karl Marx, to socialism in 1840. Cohen was also a strong opponent of Jewish nationalism.

The following year he moved to the University of Heidelberg, where he began studying philosophy and sociology under Alfred Weber, Karl Jaspers, and Heinrich Rickert. In 1922 Fromm obtained a doctorate in sociology under the supervision of Weber with a dissertation on three Jewish communities in Germany. According to Daniel Burston, the author of The Legacy of Erich Fromm (1991): "Neither Rickert nor Jaspers seem to have much effect on Fromm; their ideas are not mentioned anywhere in his published work in the form of either defense or critique."

Fromm became a devotee of Rabbi Nehemiah Nobel, a brilliant, charismatic teacher who combined classical religious instruction with a mysticism, philosophy, socialist and psychoanalysis. Fromm, along with other Nobel followers, joined Martin Buber and Gershom Scholem, as teachers in the Free Jewish Study House, the pioneering centre for adult education established by Franz Rosenzweig.

Erich Fromm met Karen Horney, a senior figure at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. Although there was a fifteen year age difference, they both felt a mutual sexual attraction. "Fromm... showed maverick, iconoclastic tendencies in his leftist views, rebelling against the social status quo. It may have been this quality, of which Karen had her share, that attracted her, or his ability to encompass his contradictory inner drives. Indeed his attempt to reconcile opposites was one hallmark of his theories, for instance the contradictions between inner psychic and external social forces, between psychoanalysis and Marxism.... As for him, he could well have experienced her in the same way other students in his class did: She represented a caring, understanding, yet at the same time strong mother figure."

After the war Fromm began a relationship with Goldie Ginsburg (who later married his friend, Leo Löwenthal). During their time together Goldie introduced him to Frieda Reichmann, a doctor who was eleven years his senior. During the war she had run a clinic for brain-injured German soldiers. Her work led to a better understanding of the physiology and pathology of brain functions. She also studied the work of Sigmund Freud at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute under Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon.

In 1923 Fromm and Reichmann opened a therapeutic facility for Jewish patients in Heidelberg. The goal was to nurture simultaneously Jewish identity and psychic health along quasi-socialist lines. As Reichmann pointed out "we first analyze the people and second made them aware of their tradition. As they were both socialists they "didn't want to go on only treating wealthy people." Patients paid what they could or donated their labour in exchange for treatment."

Reichmann's biographer, Gail A Hornstein, believed that they made a good match: "Erich was the perfect choice for Frieda. He was charming and warm... Erich also needed to be taken care of, a quality Frieda always found reassuring (in other people)." The wedding took place on 14th May, 1926. "Frieda got a good bargain; she got a man with her father's charm but more brains, who respected her independence." Reichmann later recalled: "We analyzed people as compensation for letting them work. I analyzed the housekeeper, I analyzed the cook. You may imagine what happened if they were in a phase of resistance! It was a wild affair... Erich and I had an affair. We weren't married and nobody was supposed to know about that and actually nobody did know."

In 1927 Erich Fromm commenced analytic training with Hanns Sachs and Theodor Reik. He also began associating with left-leaning therapists such as Ernst Simmel, Wilhelm Reich, Annie Reich, Helene Deutsch, Edith Jacobson, Edith Weigert and Otto Fenichel who began to take into consideration the social and political impact on the clinical situation. Together they explored ways of "finding a bridge between Marx and Freud".

Simmel, the President of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, took pride that the clinics free treatment did not differ in the least from that of patients paying high fees. "All patients are... entitled to as many weeks or months of analysis as his condition requires". In this way the Berlin Institute was fulfilling social obligations incurred by society, which "makes its poor become neurotic and, because of its cultural demands, lets its neurotics stay poor, abandoning them to their misery."

In 1928 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann set up a private practice at 15 Mönchshofstraße in Berlin. She continued a close relationship with Georg Groddeck, who was director of the Marienhöhe Sanatorium in Baden-Baden. She saw him often and they corresponded regularly. She introduced him to her husband who became his patient: "When I think of all analysts in Germany I knew, he was, in my opinion, the only one with truth, originality, courage and extraordinary kindness. He penetrated the unconscious of his patient, and yet he never hurt. Even if I was never his student in any technical sense, his teaching influenced me more than that of other teachers I had."

In 1929 Erich Fromm, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Karl Landauer, Heinrich Meng, Georg Groddeck and Ernst Schneider, established the South German Institute for Psychoanalysis in Frankfurt. After completing his psychoanalytic training Fromm opened his own private practice in Berlin.

Fromm became a patient of Groddeck. He later claimed that "many illnesses are the product of people's lifestyles. If one wants to heal them, one has to change a patient's way of life; only in very few cases can the illness be tackled through so-called specifica." In July 1931 he fell ill with tuberculosis and had to live a long time apart from Frieda. "Groddeck understood Fromm's illness as an expression of his wish to separate from his wife, at the same time showing his difficulty in coming to terms with this idea."

Later that year Fromm published his first important article, Psychoanalysis and Sociology (1929) which provided an argument for the development of social psychology: "The application of psychoanalysis to sociology must definitely guard against the mistake of wanting to give psychoanalytic answers where economic, technical, or political facts provide the real and sufficient explanation of sociological questions. On the other hand, the psychoanalyst must emphasize that the subject of sociology, society, in reality consists of individuals, and that it is these human beings, rather than abstract society as such, whose actions, thoughts, and feelings are the object of sociological research."

Fromm also gave a lecture in 1929 entitled The Application of Psycho-Analysis to Sociology and Religious Knowledge in which he outlined the basis for a rudimentary but far-reaching attempt at the integration of Freudian psychology and Marxist social theory. He decided to carry out a survey "to gain an insight into the psychic structure of manual and white-collar workers." A comprehensive questionnaire with 271 questions was designed a distributed to 3,300 recipients. By the end of 1931, Fromm and his assistant Hilde Weiss, received back 1,100 questionnaires for analysis.

Fromm asked the workers who had the real power in the State today. More than half of the answers, 56%, claimed that it was the capitalists who had the real power in Germany: "According to Marxist theory and also according to the propaganda of the left-wing parties to which many respondents referred in their replies, the real source of power, even under a democratic constitution, lies in the economic sphere. It was not surprising, therefore, that suspicions about the workings of parliamentary democracy was constantly being voiced. Although the workers' parties formed the largest faction within the Reichstag, a strong sense of disillusionment prevailed in the working class as to its actual potential for power."

The survey revealed that supporters of the Nazi Party had little sympathy for the plight of the poor or the unemployed. "The doctrine of the left-wing parties that the individual's fate is determined by his socio-economic situation was apparent in many of the answers... Significant differences between the various groups can be seen in the analysis of replies according to political orientation. Thus the majority (59%) of National Socialists believed, in significant contrast to the left-wing parties, in the self-responsibility of the individual, they usually further assumed that the unsuccessful had not used their innate capabilities and had failed to develop their character (47%). This attitude clearly shows the influence of National Socialist ideology, which stated that in the struggle for survival it is the strongest who wins out whilst the losers have revealed themselves as too weak."

Fromm discovered that the right-wing nationalists tended to hold authoritarian attitudes that "seeks out and enjoys the subjugation of men under a higher external power, whether this power is the state or a leader, natural law, the past or God". Whereas those on the left tend to "demand a freedom which allows the individual to make his own happiness... this striving for freedom is to be made possible on the basis of solidarity with others". They also share a "hatred of all powers which restrict the freedom of the individual for purposes external to that individual as well as a sympathetic identification with all oppressed or weak people."

In July, 1932, the Nazi Party won 230 seats in the Reichstag. It seemed only a matter of time before Adolf Hitler gained power. Erich Fromm, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Wilhelm Reich, Ernst Simmel, Otto Fenichel, Franz Alexander and Sandor Rado decided to leave Germany. Karen Horney decided to follow the example of her Jewish friends and boarded a ship bound for the United States. At the International Psychoanalytical Association that year President Max Eitingon, pointed out: "We have... had to give up a large number of our most valued German colleagues to the American society."

In 1933 Erich Fromm met Karen Horney when he visited Chicago. Horney had known Fromm and his wife, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann in Berlin, where all three had studied psycho-analysis. Fromm was now a divorced man and although he was fifteen years his junior, he began a sexual relationship with Horney. "Over the next decade it is impossible to sort out Fromm's influences on Horney from her influences on him in the writing they each produced... It was during the Chicago years that Fromm and Horney's intellectual relationship deepened into a romantic one."

The following year both Fromm and Horney moved to New York City. Fromm joined the faculty of the Institute for Social and Economic Research at Columbia University. Karen's friends claimed that although they did not live in the same house they spent a lot of time together. "Karen Horney's first two books, written during the early New York years, are laden with references to Fromm's works, published and unpublished. Some whispered that Horney was getting all her ideas from Fromm. The exchange, however, was anything but one-sided. The two were intertwined, emotionally and intellectually, in a relationship that must have fulfilled, perhaps for the first time in Horney's life, the dream of a marriage of minds, which she had envisioned in her letters to Oskar thirty years before."

Horney and Fromm joined a small group of exiles who had fled from Nazi Germany. This included Erich Maria Remarque, Paul Tillich, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer and Paul Kempner. Other close friends included Harold Lasswell, Karl Menninger and Harry Stack Sullivan. Hannah Tillich believed her husband were lovers. However, although she suffered terrible jealousy with some of her husband's liaisons, Hannah became very close to Karen: "She took me as a friend" and listened with "beautiful, but invisible, attention." Even though she was "gay with men, she'd never forget the woman". Hannah was very shy, and she was very grateful that Karen "would bring me out, get me to participate in the conversation."

Horney began teaching at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. She became close friends with Clara Thompson. "By temperament and personality, the two women were similar in some ways but quite different in others." One colleague who knew them both at this time commented that even though both had needs for leadership, domination and prestige, Karen "fascinated and at the same time frightened many of the students" whereas "Clara was more tender, encouraging and emotionally involved."

In her work Horney stressed the importance of culture. As a woman she had long been conscious of its role in shaping our conceptions of gender. This view had been reinforced by her observation of the differences in culture between Europe and America. Horney was therefore receptive to the work of such sociologists, anthropologists, and culturally oriented psychoanalysts as Erich Fromm, Alfred Adler, Franz Boas, Margaret Mead, Max Horkheimer, Harry Stack Sullivan, John Dollard, Harold Lasswell and Ruth Benedict.

In 1941 Erich Fromm published Escape from Freedom. In the book he reveals the influence that Karl Marx has had on his thinking: "Modern European and American history is centred around the effort to gain freedom from the political, economic, and spiritual shackles that have bound men. The battles for freedom were fought by the oppressed, those who wanted new liberties, against those who had privileges to defend. While a class was fighting for its own liberation from domination, it believed itself to be fighting for human freedom as such and thus was able to appeal to an ideal, to the longing for freedom rooted in all who are oppressed.... Despite many reverses, freedom has won battles. Many died in those battles in the conviction that to die in the struggle against oppression was better than to live without freedom. Such a death was the utmost assertion of their individuality."

Fromm argues that the First World War "was regarded by many as the final struggle and its conclusion the ultimate victory for freedom". Although Germany lost the war, its people saw the end of the monarchy and the establishment of the Weimar Republic as a move towards greater democracy. However, in some European countries, for example, Italy (1924), Portugal (1933), Germany (1934) and Spain (1939), established fascist dictatorships. "Only a few years elapsed (after the war) before new systems emerged which denied everything that men believed they had won in centuries of struggle. For the essence of these new systems, which effectively took command of man's entire social and personal life, was the submission of all but a handful of men to an authority over which they had no control."

Fromm argued against the idea that that "the victory of the authoritarian system was due to the madness of a few individuals (Benito Mussolini, Antonio Salazar, Adolf Hitler, Francisco Franco) and that their madness would lead to their downfall in due time." Some people "believed that the Italian people, or the Germans, were lacking in a sufficiently long period of training in democracy, and that therefore one could wait complacently until they had reached the political maturity of the Western democracies". Fromm also rejected the idea "that men like Hitler had gained power over the vast apparatus of the state through nothing but cunning and trickery, that they and their satellites ruled merely by sheer force; that the whole population was only the will-less object of betrayal and terror."

Fromm warned that democratic states were in danger of becoming fascist dictatorships and quotes John Dewey as saying: "The serious threat to our democracy is not the existence of foreign totalitarian states. It is the existence within our own personal attitudes and within our own institutions of conditions which have given a victory to external authority, discipline, uniformity and dependence upon The Leader in foreign countries. The battlefield is also accordingly here - within ourselves and our institutions."

In the book Fromm explores the reasons why people in Germany supported Hitler. He points out that small businessmen were especially vulnerable to the appeal of fascism: "The small or middle-sized business man who is virtually threatened by the overwhelming power of superior capital may very well continue to make profits and to preserve his independence; but the threat hanging over his head has increased his insecurity and powerlessness far beyond what it used to be. In his fight against monopolistic competitors he is staked against giants, whereas he used to fight against equals. But the psychological situation of those independent business men for whom the development of modern industry has created new economic functions is also different from that of the old independent business men."

Fromm suggests that in economically insecure time, some people are willing to give up their freedom. "The first mechanism of escape from freedom I am going to deal with is the tendency to give up the independence of one's own individual self and to fuse one's self with somebody or something outside oneself in order to acquire the strength which the individual self is lacking... The more distinct forms of this mechanism are to be found in the striving for submission and domination, or, as we would rather put it, in the masochistic and sadistic strivings as they exist in varying degrees in normal and neurotic persons respectively."

According to Fromm, fascist dictators are popular with the authoritarian personality: "The authoritarian character wins his strength to act through his leaning on superior power. This power is never assailable or changeable. For him lack of power is always an unmistakable sign of guilt and inferiority, and if the authority in which he believes shows signs of weakness, his love and respect change into contempt and hatred.... The courage of the authoritarian character is essentially a courage to suffer what fate or its personal representative or 'leader' may have destined him for. To suffer without complaining is his highest virtue - not the courage of trying to end suffering or at least to diminish it. Not to change fate, but to submit to it, is the heroism of the authoritarian character. He has belief in authority as long as it is strong and commanding."

Fromm argues that "Nazism is a psychological problem, but the psychological factors themselves have to be understood as being moulded by socio-economic factors; Nazism is an economic and political problem, but the hold it has over a whole people has to be understood on psychological grounds... In considering the psychological basis for the success of Nazism this differentiation has to be made at the outset: one part of the population bowed to the Nazi regime without any strong resistance, but also without becoming admirers of the Nazi ideology and political practice. Another part was deeply attracted to the new ideology and fanatically attached to those who proclaimed it. The first group consisted mainly of the working class and the liberal and Catholic bourgeoisie. In spite of an excellent organization, especially among the working class, these groups, although continuously hostile to Nazism from its beginning up to 1933, did not show the inner resistance one might have expected as the outcome of their political convictions. Their wish to resist collapsed quickly and since then they have caused little difficulty for the regime (excepting, of course, the small minority which has fought heroically against Nazism during all these years)."

Fromm believed that the failure of the German Revolution at the end of the First World War had a damaging impact on the political consciousness of the workers. Especially as it was the Social Democratic Party government of Friedrich Ebert, that put down the German Communist Party led revolution. This made it very difficult for the left to unite against the growth of fascism and nationalism. "Psychologically, this readiness to submit to the Nazi regime seems to be due mainly to a state of inner tiredness and resignation… is characteristic of the individual in the present era even in democratic countries. In Germany one additional condition was present as far as the working class was concerned: the defeat it suffered after the first victories in the revolution of 1918. The working class had entered the post-war period with strong hopes for the realization of socialism or at least for a definite rise in its political, economic, and social position; but, whatever the reasons, it had witnessed an unbroken succession of defeats, which brought about the complete disappointment of all its hopes. By the beginning of 1930 the fruits of its initial victories were almost completely destroyed and the result was a deep feeling of resignation, of disbelief in their leaders, of doubt about the value of any kind of political organization and political activity. They still remained members of their respective parties and, consciously, continued to believe in their political doctrines; but deep within themselves many had given up any hope in the effectiveness of political action."

Escape from Freedom from sold more than five million copies in twenty-eight different languages during the Second World War. As Lawrence J. Friedman, the author of The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love's Prophet (2014) has pointed out that the book becomes very popular every time democracy seems to be at risk in the world: "Since the Hungarian revolt of 1956, it has been surprisingly good sales wherever dictatorial regimes have been challenged."

Erich Fromm had been romanatically involved with Karen Horney since 1933. However, conflicts began to appear during the early days of the American Institute for Psychoanalysis. Fromm and Clara Thompson were angered that most of the new students were taken into analysis by Horney. According to several students at the institute Horney appeared to resent Fromm's popularity with students. Ruth Moulton has suggested that Fromm's first book in English, Escape from Freedom (1941) may have aroused Horney's jealously, particularly since he drew praise and attention from the same lay audience that admired Horney's work. Fromm was also the only teacher on the faculty who had Horney's kind of charisma.

Horney's relationship with Fromm had been in difficulty for several years. Horney told her secretary, Marie Levy, that Fromm was a "Peer Gynt type". In one of her books Horney explained what she meant by describing someone as Peer Gynt: "To thyself be enough... Provided emotional distance is sufficiently guaranteed, he may be able to preserve a considerable measure of enduring loyalty. He may be capable of having intense short-lived relationships, relationships in which he appears and vanishes. They are brittle, and any number of factors may hasten his withdrawal... As for sexual relations... he will enjoy them if they are transitory and do not interfere with his life. They should be confined, as it were, to the compartment set aside for such affairs."

One of Horney's biographers has speculated: "Horney's version of Peer Gynt/Erich Fromm suggests that the relationship with Fromm may have ended because she wanted more from him than he was willing to give. "Might she have suggested marriage, for instance, and scared him off? On the other hand, however, Fromm couldn't have been entirely averse to marriage, since he married twice after his relationship with Horney ended. Perhaps, since both his subsequent marriages were to younger women, he was looking for a less powerful partner. Horney was fifteen years older than he, had published more books, and was better known at the time.... It is also true that Horney herself possessed many of the attributes of the Peer Gynt type. Could her typing of Fromm have been a projection? Was it she, not he, who backed off when the relationship reached a certain level of intimacy?"

Another source concerned Karen Horney's daughter, Marianne. At Horney's suggestion, her daughter entered into psychoanalysis with Fromm. Marianne later admitted that her relationship with Fromm changed her life. After two years of analysis, she became aware of the artificiality of her relationship with her mother. This was followed by a wish for closer relationships, and resulted in new friendships and meeting her future husband and embarking on a "rich, meaningful" life, including "two marvelous daughters." The analysis had not provided a "cure" but had "unblocked... the capacity for growth." Marianne believes that Fromm was able to help her not only because he had been a good friend of her mother's for many years, and knew her "erratic relatedness or unrelatedness to people." As a result, he was able to "affirm a reality which I had never been able to grasp."

In April 1943, a group of students requested that Fromm teach a clinical course in the institute program. Horney rejected the idea and argued that allowing a non-physician to teach clinical courses would make it more difficult for their institute to be accepted as a training program within New York Medical College. At a vote in the faculty council, Horney's proposal was victorious. Fromm, who was working as a training analyst in the privacy of his office, where he was analyzing and supervising students, was officially deprived of training status. As a result, he resigned, along with Clara Thompson, Harry Stack Sullivan and Janet Rioch.

A large number of students were upset by this dispute. Ralph Rosenberg wrote to Ruth Moulton: "We children should get together and spank our unruly parents for their childish behaviour. The students may hold the balance of power in the mess. Thompson expects to recruit enough students from our gang and other sources to start a third school... The faculty has little to gain by the split and its undivided loyalty. The faculty has little to gain by the split and its accompanying mud slinging. The students lose the services of outstanding teachers... We do not know the actual issues causing the split... I therefore suggest that the students invite the Fromm and Horney group to discuss their differences in the presence of the students."

Fromm, Thompson, Sullivan and Rioch, along with eight others, including Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, established their own institution, the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology. Horney was deeply hurt by this development and told a Ernest Schachtel, who took holidays with the couple in happier times, that she unwilling for their friendship to continue unless he stopped seeing Fromm. Schachtel refused: "I was surprised she would make such a condition. I continued to see him, because we were old friends... I think she was deeply hurt by Erich Fromm."

Fromm was an active member of the Socialist Party of America and published several successful books including. Man for Himself (1947), Psychoanalysis and Religion (1951) and The Sane Society (1955). He was also an outspoken critic of McCarthyism, the Cold War, the Vietnam War and a supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. According to Daniel Burston, the author of The Legacy of Erich Fromm (1991): "Despite his outspoken opposition to the Cold War, nuclear arms, and the Vietnam War, there is no public record of Fromm having suffered from the kind of official harassment, persecution, and character assassination that became the commonplaces of other people's lives during the McCarthy era and its aftermath."

Erich Fromm published his most successful book, The Art of Loving in 1956. He attempts to explain why love is so important to the human race: "Man is gifted with reason; he is life being aware of itself; he has awareness of himself, of his fellow man, of his past, and of the possibilities of his future. This awareness of himself as a separate entity, the awareness of his own short life span, of the fact that without his will he is born and against his will he dies, that he will die before those whom he loves, or they before him, the awareness of his aloneness and separateness, of his helplessness before the forces of nature and of society, all this makes his separate, disunited existence an unbearable prison. He would become insane could he not liberate himself from this prison and reach out, unite himself in some form or other with men, with the world outside."

Fromm argues that humans have needed to love each other from the beginning of time: "The unity achieved in productive work is not interpersonal; the unity achieved in orgiastic fusion is transitory; the unity achieved by conformity is only pseudo-unity. Hence, they are only partial answers to the problem of existence. The full answer lies in the achievement of interpersonal union, of fusion with another person, in love... This desire for interpersonal fusion is the most powerful striving in man. It is the most fundamental passion, it is the force which keeps the human race together, the clan, the family, society. The failure to achieve it means insanity or destruction - self-destruction or destruction of others. Without love, humanity could not exist for a day."

According to Fromm we learn about love from our parents: "For most children before the age from eight and a half to ten, the problem is almost exclusively that of being loved - of being loved for what one is. The child up to this age does not yet love; he responds gratefully, joyfully to being loved. At this point of the child's development a new factor enters into the picture: that of a new feeling; of producing love by one's own activity. For the first time, the child thinks of giving something to mother (or to father), of producing something - a poem, a drawing, or whatever it may be. For the first time in the child's life the idea of love is transformed from being loved into loving: into creating love. It takes many years from this first beginning to the maturing of love. Eventually the child, who may now be an adolescent, has overcome his egocentricity; the other person is not any more primarily a means to the satisfaction of his own needs. The needs of the other person are as important as his own - in fact, they have become more important. To give has become more satisfactory, more joyous, than to receive; to love; more important even than being loved. By loving, he has left the prison cell of aloneness and isolation which was constituted by the state of narcissism and self-centredness. He feels a sense of new union, of sharing, of oneness." Infantile love follows the principle: "I love because I am loved." Mature love follows the principle: "I am loved because I love." Immature love says: "I love you because I need you." Mature love says: "I need you because I love you."

Fromm claims that there are essential differences in quality between motherly and fatherly love. "Motherly love by its very nature is unconditional. Mother loves the newborn infant because it is her child, not because the child has fulfilled any specific condition, or lived up to any specific expectation.... Unconditional love corresponds to one of the deepest longings, not only of the child, but of every human being; on the other hand, to be loved because of one's merit, because one deserves it, always leaves doubt; maybe I did not please the person whom I want to love me, maybe this, or that - there is always a fear that love could disappear.... No wonder that we all cling to the longing for motherly love, as children and also as adults. Most children are lucky enough to receive motherly love... As adults the same longing is much more difficult to fulfil. In the most satisfactory development it remains a component of normal erotic love; often it finds expression in religious forms, more often in neurotic forms."

The relationship to father is quite different. "Mother is the home we come from, she is nature, soil, the ocean; father does not represent any such natural home. He has little connection with the child in the first years of its life, and his importance for the child in this early period cannot be compared with that of mother. But while father does not represent the natural world, he represents the other pole of human existence; the world of thought, of man-made things, of law and order, of discipline, of travel and adventure. Father is the one who teaches the child, who shows him the road into the world." Fromm argues that fatherly love is conditional love. Its principle is "I love you because you fulfil my expectations, because you do your duty, because you are like me."

Fromm insists that the parents should prepare them for independence: "Mother should have faith in life, hence not be over-anxious, and thus not infect the child with her anxiety. Part of her life should be the wish that the child become independent and eventually separate from her. Father's love should be guided by principles and expectations; it should be patient and tolerant, rather than threatening and authoritarian. It should give the growing child an increasing sense of competence and eventually permit him to become his own authority and to dispense with that of father."

Erich Fromm then goes on to discuss erotic love. "Brotherly love is love among equals; motherly love is love for the helpless. Different as they are from each other, they have in common that they are by their very nature not restricted to one person. If I love my brother, I love all my brothers; if I love my child, I love all my children; no, beyond that, I love all children, all that are in need of my help. In contrast to both types of love is erotic love; it is the craving for complete fusion, for union with one other person. It is by its very nature exclusive and not universal; it is also perhaps the most deceptive form of love there is.... it is often confused with the explosive experience of 'falling' in love, the sudden collapse of the barriers which existed until that moment between two strangers.... this experience of sudden intimacy is by its very nature short-lived. After the stranger has become an intimately known person there are no more barriers to be overcome, there is no more sudden closeness to be achieved. The 'loved' person becomes as well known as oneself. Or, perhaps I should better say as little known."

Erich Fromm attempts to explain the importance of self-love: "Granted that love for oneself and for others in principle is conjunctive, how do we explain selfishness, which obviously excludes any genuine concern for others? The selfish person is interested only in himself, wants everything for himself, feels no pleasure in giving, but only in taking. The world outside is looked at only from the standpoint of what he can get out of it; he lacks interest in the needs of others, and respect for their dignity and integrity. He can see nothing but himself; he judges everyone and everything from its usefulness to him; he is basically unable to love.... The selfish person does not love himself too much but too little; in fact he hates himself. This lack of fondness and care for himself, which is only one expression of his lack of productiveness, leaves him empty and frustrated. He is necessarily unhappy and anxiously concerned to snatch from life the satisfactions which he blocks himself from attaining. He seems to care too much for himself, but actually he only makes an unsuccessful attempt to cover up and compensate for his failure to care for his real self. Freud holds that the selfish person is narcissistic, as if he had withdrawn his love from others and turned it towards his own person. It is true that selfish persons are incapable of loving others, but they are not capable of loving themselves either."

Fromm stressed the importance of good communication in close relationships. "To be concentrated in relation to others means primarily to be able to listen. Most people listen to others, or even give advice, with out really listening. They do not take the other person's talk seriously, they do not take their own answers seriously either. As a result, the talk makes them tired. They are under the illusion that they would be even more tired if they listened with concentration. But the opposite is true. Any activity, if done in a concentrated fashion, makes one more awake (although afterwards natural and beneficial tiredness sets in), while every unconcentrated activity makes one sleepy - while at the same time it makes it difficult to fall asleep at the end of the day."

Fromm believed strongly that to love someone deeply we need to be sensitive to the needs of others. "If we look at the situation of being sensitive to another human being, we find the most obvious example in the sensitiveness and responsiveness of a mother to her baby. She notices certain bodily changes, demands, anxieties, before they are overtly expressed. She wakes up because of her child's crying, where another and much louder sound would not waken her. All this means that she is sensitive to the manifestations of the child's life; she is not anxious or worried, but in a state of alert equilibrium, receptive to any significant communication coming from the child. In the same way one can be sensitive towards oneself. One is aware, for instance, of a sense of tiredness or depression, and instead of giving in to it and supporting it by depressive thoughts which are always at hand, one asks oneself what happened? Why am I depressed? The same is done by noticing when one is irritated or angry, or tending to daydreaming, or other escape activities. In each of these instances the important thing is to be aware of them, and not to rationalise them in-the thousand and one ways in which this can be done; furthermore, to be open to our own inner voice which will tell us - often rather immediately - why we are anxious, depressed, irritated."

Fromm believes that for society to function well, we need to express brotherly love. "The most fundamental kind of love, which underlies all types of love, is brotherly love. By this I mean the sense of responsibility, care, respect, knowledge of any other human being, the wish to further his life. This is the kind of love the Bible speaks of when it says: love thy neighbour as thyself. Brotherly love is love for all human beings; it is characterised by its very lack of exclusiveness. If I have developed the capacity for love, then I cannot help loving my brothers. In brotherly love there is the experience of union with all men, of human solidarity, of human at-onement. Brotherly love is based on the experience that we all are one. The differences in talents, intelligence, knowledge are negligible in comparison with the identity of the human core common to all men."

However, Fromm argues that brotherly love is undermined by a capitalist system that forces us to compete with each other. "What is the outcome? Modern man is alienated from himself, from his fellow men, and from nature. He has been transformed into a commodity, experiences his life forces as an investment which must bring him the maximum profit obtainable under existing market conditions. Human relations are essentially those of alienated automatons, each basing his security on staying close to the herd, and not being different in thought, feeling or action. While everybody tries to be as close as possible to the rest, everybody remains utterly alone, pervaded by the deep sense of insecurity, anxiety and guilt which always results when human separateness cannot be overcome."

Erich Fromm answer to this problem is to dramatically change society. "If man is to be able to love, he must be put in his supreme place. The economic machine must serve him, rather than he serve it. He must be enabled to share experience, to share work, rather than, at best, share in profits. Society must be organised in such a way that man's social, loving nature is not separated from his social existence, but becomes one with it. If it is true, as I have tried to show, that love is the only sane and satisfactory answer to the problem of human existence, then any society which excludes, relatively, the development of love, must in the long run perish of its own contradiction with the basic necessities of human nature. Indeed, to speak of love is not 'preaching', for the simple reason that it means to speak of the ultimate and real need in every human being. That this need has been obscured does not mean that it does not exist. To analyse the nature of love is to discover its general absence today and to criticise the social conditions which are responsible for this absence. To have faith in the possibility of love as a social and not only exceptional-individual phenomenon, is a rational faith based on the insight into the very nature of man."

Since publication of The Art of Loving has sold more than twenty-five million globally. Lawrence J. Friedman has pointed out: "It is a favourite of my Harvard undergraduates today as it was with my classmates at the University of California half a century ago. For generations, it has been a volume with remarkable ties to its readers' personal and social lives."

Other books by Erich Fromm include Sigmund Freud's Mission (1959), Marx's Concept of Man (1961), The Dogma of Christ (1963), The Heart of Man (1964), The Revolution of Hope (1968), The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973) and To Have Or to Be? (1976).

On this day in 1891 John Bent, was born at Stowmarket. His father, Spencer Bent, was serving with the Royal Horse Artillery, and was later to be killed in the Boer War. At the age of fourteen Bent enlisted with the East Lancashire Regiment. After spending four years in Ireland he was based in Woking (1909-12) and Colchester (1912-14).

On the outbreak of the First World War, Bent went as a member of the British Expeditionary Force to France, and arrived in time to take part in the battles at the Marne and the Aisne Valley. In September his regiment was moved to Ypres in Belgium.

On 21st October the Germans captured the village of Le Gheer. Bent was a member of the 11th Brigade sent to recapture the village. Heavy fighting took place over the next few days. Eventually the British soldiers gained the village but on the 27th October the Germans launched a counter-attack.

One of the British soldiers, Private McNulty, was shot after leaving the trench. As he was being fired at by the Germans, Bent volunteered to go out and bring him back. McNulty was over 25 yards away and Bent came under heavy fire as he dragged the man to safety. Bent was awarded the Victoria Cross for his act of bravery. The medal was presented to Bent by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 9th December 1914.

Bent had been wounded in the leg while rescuing McNulty and it took several months to recover. Promoted to the rank of Sergeant, Bent returned to the Western Front in the summer of 1916. Badly injured at the Battle of the Somme, Bent was sent home to England.

After recovering his health he returned to the Western Front and on 3rd November 1918, won the Military Medal for "bravery in the field". Company Sergeant Major Bent remained in the British Army after the war, serving in the West Indies and Malta before retiring in July 1925.

After leaving the army Bent became a janitor at Paragon School in the New Kent Road, London. Later he worked as a commissionaire for Courage, the brewers. In August 1968 Bent was invited to open a new Courage public house, The Victoria Cross, in Chatham, Kent. Bent stayed with Courage until he was eighty-five years old. John Bent died the following year on 3rd May, 1977.

On this day in 1893 the war poet Wilfred Owen, the eldest of the three sons and one daughter of Thomas Owen, a railway clerk and his wife, Susan Shaw Owen, was born at Plas Wilmot, near Oswestry, on 18th March, 1893. His father, a railway clerk, was transferred to Birkenhead in 1898, and between 1899 and 1907 Owen was educated at the Birkenhead Institute. In 1907 the family moved to Shrewsbury, where Thomas Owen had been appointed assistant superintendent of the Joint Railways and Wilfred attended Shrewsbury Technical School.

As his biographer, Jon Stallworthy, has pointed out: "Under the strong influence of his devout mother he read a passage from the Bible every day and, on Sundays, would rearrange her sitting-room to represent a church. Then, wearing a linen surplice and cardboard mitre she had made, he would summon the family and conduct a complete evening service with a carefully prepared sermon."

Owen left school in 1911, eager to go to university, and passed the University of London matriculation exam, though not with the first-class honours necessary to win him the scholarship he needed. His mother persuaded him to accept the offer of an unpaid position as lay assistant to the Revd Herbert Wigan, vicar of Dunsden. In return Wigan promised some tuition to prepare him for the university entrance exam. It has been claimed that this was not a success as Wigan had no interest in literature, and Owen had lost interest in theology, the only topic offered for tuition.

During this period he came under the influence of Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats and began writing poetry. In July he sat a scholarship exam for University College, but failed, and in mid-September crossed the channel to take up a part-time post teaching English at the Berlitz School in Bordeaux. This was followed by becoming a tutor for a eleven-year-old French girl in her parents' villa, in the Pyrenees.

Owen continued to write poetry and became friends with the French poet and political activist, Laurent Tailhade. He became interested in Tailhade's ideas on modern poetry as well as his political views that embraced anarchism and pacifism. Tailhade, a poet of the so-called "decadent" school, also introduced him to the work of Paul Verlaine and Gustave Flaubert.

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 created a strong wave of patriotism and even though Tailhade had written two pacifist pamphlets he joined the French Army. Owen was concerned that he would be unable to cope as a soldier. However, he was aware it would give him the opportunity to write about something very important. He wrote to his mother: "Do you know what would hold me together on a battlefield? The sense that I was perpetuating the language in which Keats and the rest of them wrote!"

Owen finally returned to England, and, on 21st October 1915, he enlisted in the Artists' Rifles. Owen spent the next seven and a half months training for service on the front-line. While based at Hare Hall camp near Romford he met Harold Monro, the owner of the Poetry Bookshop in Devonshire Street and the editor of the Poetry Review, a magazine he had started in 1912. Monro read some of Owen's poems and gave him encouraging advice.

On 4th June 1916 Owen was commissioned into the Manchester Regiment and after further training he crossing to France on 29th December. He arrived on the Western Front at the Somme in January 1917. While at the front Owen began writing poems about his war experiences. This included being trapped for three days in a shell-hole with the mangled corpse of a fellow officer. After heavy artillery bombardment he was also blown out of his trench and on 1st May he was diagnosed as suffering from shell-shock and was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh, to recuperate.

While in hospital he met Siegfried Sassoon, who had just published his statement Finished With War: A Soldier's Declaration, which announced that "I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them and that had this been done the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation." Instead of the expected court martial, the under-secretary for war declared him to be suffering from shell-shock, and he was sent to Cocklockhart.

Sassoon was also a poet and his first volume of poems, The Old Huntsman, had just been published. Sassoon introduced Owen to Robert Graves, who was also recovering from wounds received at the front. His book of poems, Fairies and Fusiliers, had also been published in 1917. Sassoon suggested that Owen should write in a more direct, colloquial style. Over the next few months Owen wrote a series of poems, including Anthem for Doomed Youth, Disabled and Dulce et Decorum Est. Owen was also supported by his doctor, Arthur J. Brock, who arranged for two of of Owen's poems to be published in the hospital's literary journal, The Hydra.

Until he met Sassoon his few war poems had been patriotic and heroic. Under the influence of Sassoon his thoughts and style changed dramatically. During this time he wrote: "All a poet can do today is warn. That is why the true Poets must be truthful". Jon Stallworthy has pointed out: "The older poet's advice and encouragement, showing the younger how to channel memories of battle - recurring in obsessive nightmares which were a symptom of shell-shock - into a poem such as Dulce et decorum est, complemented Dr Brock's ‘work-cure’. The final manuscript of Anthem for Doomed Youth carries suggestions (including that of the title) in Sassoon's handwriting. Owen's confidence grew, his health returned, and in October a medical board decided that he was fit for light duties."

Sassoon also introduced Owen to H. G. Wells and Arnold Bennett and they helped him get some of his poems published in The Nation. Owen also had talks with William Heinemann about the publication of a collection of his poems. Another friend he acquired through Sassoon was Robert Ross, who had enjoyed a long-term relationship with Oscar Wilde. According to Maureen Borland, the author of Wilde's Devoted Friend: Life of Robert Ross (1990): "In Ross's delightful and witty company, for a few precious hours, they could forget the horrors of trench warfare. Although these men were not among his partners, Ross was clearly homosexual and had two long-term relationships. He shared a house for fifteen years with (William) More Adey; a shorter partnership, with Frederick (Freddie) Stanley Smith, ended in 1917, when Smith took up a diplomatic appointment in Stockholm. Ross discouraged discussion of his sex life, and maintained a lifelong silence about the exact nature of his relationship with Wilde."