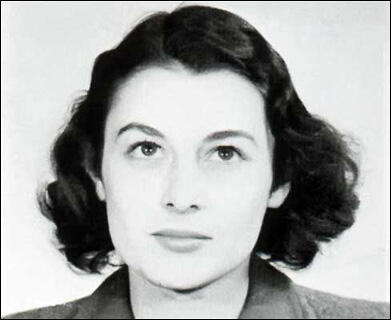

Violette Szabo

Violette Bushell, the daughter of an English father and a French mother, was born in France on 26th June, 1921. She spent her early childhood in Paris where her father drove a taxi. Later the family moved to London and she was educated at a Brixton Secondary School. At the age of fourteen Violette left school and became a hairdresser's assistant. Later she found work as a sales assistant at Woolworths in Oxford Street.

During the Second World War Violette met Etienne Szabo, an officer in the Free French Army. The couple decided to get married (21st August 1940) when they discovered that Etienne was about to be sent to fight in North Africa.

Soon after giving birth to a daughter, Tania Szabo, Violette heard that her husband had been killed at El Alamein. She now developed a strong desire to get involved in the war effort and eventually joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE). She told a fellow recruit: "My husband has been killed by the Germans and I'm going to get my own back."

At first SOE officers had doubts about whether Violette should be sent to France. One officer wrote: "She speaks French with an English accent. Has no initiative; is completely lost when on her own. Another officer argued: "This student is temperamentally unsuitable... When operating in the field she might endanger the lives of others."

Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, head of SOE's French operations, overruled these objections and after completing her training Violette was parachuted into France where she had the task of obtaining information about the resistance possibilities in the Rouen area. Despite being arrested by the French police she completed her mission successfully and after being in occupied territory for six weeks she returned to England.

Violette returned to France in June 1944 but while with Jacques Dufour, a member of the French Resistance, was ambushed by a German patrol. By providing covering fire Szabo enabled Dufour to escape. Szabo was captured and taken to Limoges and then to Paris. After being tortured by the Gestapo she was sent to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in Germany.

Some time in the spring of 1945, with Allied troops closing in on Nazi Germany, Violette Szabo was executed. She was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre and the George Cross. Her story is told in the book and film entitled Carve Her Name With Pride.

Primary Sources

(1) Captain Selwyn Jepson was SOE's senior recruiting officer. He was interviewed by the Imperial War Museum for its Sound Archive.

I was responsible for recruiting women for the work, in the face of a good deal of opposition, I may say, from the powers that be. In my view, women were very much better than men for the work. Women, as you must know, have a far greater capacity for cool and lonely courage than men. Men usually want a mate with them. Men don't work alone, their lives tend to be always in company with other men. There was opposition from most quarters until it went up to Churchill, whom I had met before the war. He growled at me, "What are you doing?" I told him and he said, "I see you are using women to do this," and I said, "Yes, don't you think it is a very sensible thing to do?" and he said, "Yes, good luck to you'" That was my authority!

(2) Patrick Howarth was a member of the Special Operations Executive during the Second World War. He wrote about Violette Szabo in his book Undercover: The Men and Women of the Special Operations Executive (1980)

Apart from her excellent French her most evident qualification for service in SOE was an exceptional talent for shooting, which caused her to be banned from some of London's West End galleries because she won too many prizes. Nevertheless Selwyn Jepson, to whom she had been recommended, thought she might be a suitable recruit. His principle doubt arose from the readiness with which she volunteered for service. He wondered for a time whether she might belong to a category which he had learnt, with reason, to distrust, that of agents with a suicidal urge.

(3) SOE report on Violette Szabo (1943)

I seriously wonder whether this student is suitable. She speaks French with an English accent. Has no initiative; is completely lost when on her own.

(4) Maurice Buckmaster was the officer at the Special Operations Executive who gave her the instructions for her second mission to France.

Violette got up rather nervously as I went into the room. She was really beautiful, dark-haired and olive-skinned, with that kind of porcelain clarity of face and purity of bone that one finds occasionally in the women of the south-west of France.

"When you land, you will be received by a group organized by Clement. I showed her on the large-scale Michelin map the exact area where the drop was to rake place. She carefully memorized the geographical features of the area, tracing the path she would follow through the wood to the side-road which led to the farm cottages where she would spend the rest of the night and the whole of the next day.

(5) Jacques Dufour, French Resistance leader, report to SOE (1944)

We heard the rumble of armoured cars and machine-guns began spraying close to us they could follow our progress by the movement of the wheat. When we weren't more than yards from the edge of the wood Szabo, who had her clothes ripped to ribbons and was bleeding from numerous cuts all over her legs, told me she was unable to go one inch further. She insisted she wanted me to try to get away, that there was no point in my staying with her. So I went on and managed to hide under a haystack.

(6) Julie Barry, News of the World (31st March, 1946)

I was caught by the Germans for sabotage in Guernsey and imprisoned there at first and then in many other prisons in France and Germany before being sent to Ravensbriick. I spoke several European languages and the staff of the prisons made use of me as an interpreter. At Ravensbriick, I was made a prison policewoman and given the number 39785 and a red armband that indicated my status.

I was handed a heavy leather belt with instructions to beat the women prisoners. It was a hateful task, but in it I saw my only chance to help some of the condemned women.

It was into this camp that three British parachutists were brought. One was Violette Szabo. They were in rags, their faces black with dirt, and their hair matted. They were starving. They had been tortured in attempts to wrest from them secrets of the invasion but I am certain they gave nothing away.

(7) Leo Marks wrote a poem about a girlfriend, Ruth Hambo, who was killed in an air crash in Canada. Marks later gave the poem as a ciphar to Violette Szabo.

The life that I have is all that I have

And the life that I have is yours

The love that I have of the life that I have

Is yours and yours and yours.

A sleep I shall have, a rest I shall have

And death will be but a pause

For the years I shall have in the long green grass

Are yours and yours and yours.

(8) Violette Szabo's citation for the George Cross (1945)

Violette Szabo was continuously and atrociously tortured, but never by word or deed gave away any of her acquaintances or told the enemy anything of any value.