On this day on 16th August

On this day in 1819 the Peterloo Massacre takes place. In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer. The main objective of this new organisation was to obtain parliamentary reform and during the summer of 1819 it was decided to invite Major John Cartwright, Henry Orator Hunt and Richard Carlile to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The men were told that this was to be "a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone. I think by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country." Cartwright was unable to attend but Hunt and Carlile agreed and the meeting was arranged to take place at St. Peter's Field on 16th August.

Samuel Bamford, a handloom weaver, walked from Middleton to be at the meeting that day: "Every hundred men had a leader, who was distinguished by a spring of laurel in his hat, and the whole were to obey the directions of the principal conductor, who took his place at the head of the column, with a bugleman to sound his orders. At the sound of the bugle not less than three thousand men formed a hollow square, with probably as many people around them, and I reminded them that they were going to attend the most important meeting that had ever been held for Parliamentary Reform. I also said that, in conformity with a rule of the committee, no sticks, nor weapons of any description, would be allowed to be carried. Only the oldest and most infirm amongst us were allowed to carry their walking staves. Our whole column, with the Rochdale people, would probably consist of six thousand men. At our head were a hundred or two of women, mostly young wives, and mine own was amongst them. A hundred of our handsomest girls, sweethearts to the lads who were with us, danced to the music. Thus accompanied by our friends and our dearest we went slowly towards Manchester."

The local magistrates were concerned that such a substantial gathering of reformers might end in a riot. The magistrates therefore decided to arrange for a large number of soldiers to be in Manchester on the day of the meeting. This included four squadrons of cavalry of the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), a detachment of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (120 men) and all Manchester's special constables (400 men).

At about 11.00 a.m. on 16th August, 1819 William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field at midday. Hulton therefore took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying.

The main speakers at the meeting arrived at 1.20 p.m. This included Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Richard Carlile, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and Mary Fildes. Several of the newspaper reporters, including John Tyas of The Times, Edward Baines of the Leeds Mercury, John Smith of the Liverpool Mercury and John Saxton of the Manchester Observer, joined the speakers on the hustings.

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". William Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest Henry Hunt and the other leaders of the demonstration. Nadin replied that this could not be done without the help of the military. Hulton then wrote two letters and sent them to Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange, the commander of the military forces in Manchester and Major Thomas Trafford, the commander of the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry.

Major Trafford, who was positioned only a few yards away at Pickford's Yard, was the first to receive the order to arrest the men. Major Trafford chose Captain Hugh Birley, his second-in-command, to carry out the order. Local eyewitnesses claimed that most of the sixty men who Birley led into St. Peter's Field were drunk. Birley later insisted that the troop's erratic behaviour was caused by the horses being afraid of the crowd.

The Manchester & Salford Yeomanry entered St. Peter's Field along the path cleared by the special constables. As the yeomanry moved closer to the hustings, members of the crowd began to link arms to stop them arresting Henry Hunt and the other leaders. Others attempted to close the pathway that had been created by the special constables. Some of the yeomanry now began to use their sabres to cut their way through the crowd.

When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they arrested Henry Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson, George Swift, John Saxton, John Tyas, John Moorhouse and Robert Wild. As well as the speakers and the organisers of the meeting, Birley also arrested the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks."

Samuel Bamford was another one in the crowd who witnessed the attack on the crowd: "The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads... On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled... A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises. In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again."

Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange reported to William Hulton at 1.50 p.m. When he asked Hulton what was happening he replied: "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry? Disperse them." L'Estrange now ordered Lieutenant Jolliffe and the 15th Hussars to rescue the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry. By 2.00 p.m. the soldiers had cleared most of the crowd from St. Peter's Field. In the process, 18 people were killed and about 500, including 100 women, were wounded.

Some historians have argued that Lord Liverpool, the prime minister, and Lord Sidmouth, his home secretary, were behind the Peterloo Massacre. However, Donald Read, the author of Peterloo: The Massacre and its Background (1958) disagrees with this interpretation: "Peterloo, as the evidence of the Home Office shows, was never desired or precipitated by the Liverpool Ministry as a bloody repressive gesture for keeping down the lower orders. If the Manchester magistrates had followed the spirit of Home Office policy there would never have been a massacre."

E. P. Thompson disagrees with Read's analysis. He has looked at all the evidence available and concludes: "My opinion is (a) that the Manchester authorities certainly intended to employ force, (b) that Sidmouth knew - and assented to - their intention to arrest Hunt in the midst of the assembly and to disperse the crowd, but that he was unprepared for the violence with which this was effected."

Richard Carlile managed to avoid being arrested and after being hidden by local radicals, he took the first mail coach to London. The following day placards for Sherwin's Political Register began appearing in London with the words: 'Horrid Massacres at Manchester'. A full report of the meeting appeared in the next edition of the newspaper. The authorities responded by raiding Carlile's shop in Fleet Street and confiscating his complete stock of newspapers and pamphlets.

James Wroe was at the meeting and he described the attack on the crowd in the next edition of the Manchester Observer. Wroe is believed to be the first person to describe the incident as the Peterloo Massacre. Wroe also produced a series of pamphlets entitled The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events. The pamphlets, which appeared for fourteen consecutive weeks from 28th August, price twopence, had a large circulation, and played an important role in the propaganda war against the authorities. Wroe, like Carlile, was later sent to prison for writing these accounts of the Peterloo Massacre.

Moderate reformers in Manchester were appalled by the decisions of the magistrates and the behaviour of the soldiers. Several of them wrote accounts of what they had witnessed. Archibald Prentice sent his report to several London newspapers. When John Edward Taylor discovered that John Tyas of The Times, had been arrested and imprisoned, he feared that this was an attempt by the government to suppress news of the event. Taylor therefore sent his report to Thomas Barnes, the editor of The Times. The article that was highly critical of the magistrates and the yeomanry was published two days later.

Tyas was released from prison. The Times mounted a campaign against the action of the magistrates at St. Peter's Field. In one editorial the newspaper told its readers "a hundred of the King's unarmed subjects have been sabred by a body of cavalry in the streets of a town of which most of them were inhabitants, and in the presence of those Magistrates whose sworn duty it is to protect and preserve the life of the meanest Englishmen." As these comments came from an establishment newspaper, the authorities found this criticism particularly damaging.

Other journalists at the meeting were not treated as well as Tyas. Richard Carlile wrote an article on the Peterloo Massacre in the next edition of The Republican. Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. The authorities also disapproved of Carlile publishing books by Tom Paine, including Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to three years in Dorchester Gaol.

Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated. Carlile was determined not to be silenced. While he was in prison he continued to write material for The Republican, which was now being published by his wife. Due to the publicity created by Carlile's trial, the circulation of The Republican increased dramatically and was now outselling pro-government newspapers such as The Times.

In the first trial of those people who attended the meeting at St. Peter's Field, the judge commented: "I believe you are a downright blackguard reformer. Some of you reformers ought to be hanged, and some of you are sure to be hanged - the rope is already round your necks."

James Wroe was at the meeting and he described the attack on the crowd in the next edition of the Manchester Observer. Wroe is believed to be the first person to describe the incident as the Peterloo Massacre. Wroe also produced a series of pamphlets entitled The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events. The pamphlets, which appeared for fourteen consecutive weeks from 28th August, price twopence, had a large circulation, and played an important role in the propaganda war against the authorities. The government wanted revenge and Wroe was arrested and charged with producing a seditious publication. He was found guilty and sentenced to twelve months in prison, plus a £100 fine.

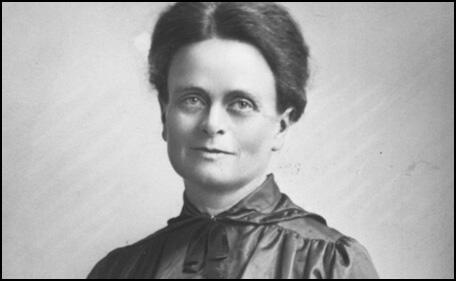

On this day in 1827 Frances Buss, the daughter of Robert Buss and Frances Fleetwood was born on 16th August 1827. Robert Buss was an engraver but he was fairly unsuccessful and the family were extremely poor. Frances was the eldest of ten children, but only five of them survived beyond childhood.

Frances attended a local free school. Frances Buss did very well with her studies and at the age of fourteen she was asked to help teach the other children. Inspired by her daughter's educational achievements, Mrs. Buss decided to open her own school and Frances was given the job of teaching the older children. Frances had a strong desire to improve the standard of her teaching and in 1849 she became an evening student at the recently established Queen's College.

Inspired by her training, Buss decided to start her own school and in 1850 she established the North London Collegiate School for Girls. In an attempt to achieve and maintain high standards, Buss only employed qualified teachers. She also made use of visiting lecturers from Queen's College.

The North London Collegiate School soon developed a reputation for providing an excellent education for its students. Other women involved in the campaign to improve the education of women visited the school. This included Emily Davies who was to persuade the authorities to allow women to become students at London University. The two women became close friends and became involved in the campaign to secure the admission of girls to the Oxford and Cambridge examinations. In 1864 the Schools Enquiry Commission agreed to look into gender inequalities in education. In 1865 Frances Buss gave evidence to the commission.

In 1865 Frances Buss joined with Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Helen Taylor and Dorothea Beale to form a woman's discussion group called the Kensington Society. The following year the group formed the London Suffrage Committee and began organizing a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

Buss remained a strong supporter of universal suffrage. She also worked closely with Josephine Butler and helped her with campaigns against the white slave trade and the Contagious Diseases Act.

In 1871 Frances took the decision to change her North London Collegiate School from a private school to an endowed grammar school. Although this resulted in a loss of income, Buss was now able to offer a good education for those girls whose families could not afford the fees of a private school.

In 1880 Frances Buss began to suffer from a debilitating kidney disease, although she continued running the North London Collegiate School until her death on 24th December 1894.

On this day in 1864 Elsie Inglis, the second daughter of John Inglis (1820–1894), who worked for the East India Company, was born at Naini Tal, in India. When her father retired from his job in 1878 the Inglis family returned to Scotland and settled in Edinburgh.

In 1878 Elsie began her education at the Edinburgh Institution for the Education of Young Ladies and at eighteen she went to a finishing school in Paris for a year.

Elsie Inglis lived a life of leisure until Sophia Jex-Blake opened the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women in 1886. With the support of her father, she began to train as a doctor. When Dr. Jex-Blake, dismissed two students for what Inglis considered to be a trivial offence, she obtained funds from her father and some of his wealthy friends, and established a rival medical school, the Scottish Association for the Medical Education for Women. Subsequently she studied for eighteen months at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. After completing her training she went to work for the New Hospital for Women, opened by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in 1890.

Elsie Inglis supported women's suffrage and had joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage while a student in Edinburgh. In 1892 she became more active in the campaign and agreed to the suggestion made by Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy to make speeches on women's medical education. She also joined the National Union of Suffrage Societies during this period.

In 1894 Inglis returned to Edinburgh and set up in practice with Dr. Jessie MacGregor, who had been a fellow student at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, and in 1898 opened a hall of resistance for women medical students. The following year Inglis was appointed lecturer in gynaecology at the Medical College for Women. She also opened a small hospital for women in George Square.

As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "In addition to her medical work, from 1900 she was a very active suffrage campaigner in Scotland, speaking at up to four meetings a week, travelling the length and breadth of the country.... From 1909 Elsie Inglis, who was already honorary secretary of the Edinburgh National Suffrage Society, became secretary of the newly-formed Federation of Scottish Suffrage Societies."

It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Inglis was a lesbian and lived for many years with Flora Murray, who later had a romantic relationship with Louisa Garrett Anderson.

Inglis was a strong supporter of the National Union of Suffrage Societies strategy to obtain the vote. She joined with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy in signing the letter published in Votes for Women, on 26th July 1912 that protested against the arson campaign that had been unleashed by the Women Social & Political Union.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Inglis applied to Louisa Garrett Anderson for a place in the Women's Hospital Corps, but was told that they already had enough volunteers. Inglis now suggested that women's medical units should be allowed to serve on the Western Front. However, the War Office, rebuffed with the words, "My good lady, go home and sit still." Inglis now took the idea to the Scottish Federation of Women's Suffrage Societies, which agreed to form a hospitals committee. The Common Cause, the journal of the National Union of Suffrage Societies, also published a plea for funds and she was able to establish the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH).

As her biographer, Leah Leneman, has pointed out: "The War Office may have spurned the idea of all-women medical units, but other allies were desperate for help, and both the French and the Serbs accepted the offer. The first unit left for France in November 1914 and a second unit went to Serbia in January 1915. Inglis was torn between her desire to oversee the fund-raising and organizational side of the SWH and her desire to serve in the field, but in mid-April the chief medical officer of the first Serbian unit fell ill, and Inglis went out to replace her. During the summer she set up two further hospital units."

By 1915 the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit had established an Auxiliary Hospital with 200 beds in the 13th century Royaumont Abbey. Her team included Evelina Haverfield, Ishobel Ross and Cicely Hamilton. In April 1915 Elsie Inglis took a women's medical unit to Serbia. During an Austrian offensive in the summer of 1915, Inglis was captured but eventually, with the help of American diplomats, the British authorities were able to negotiate the release of Inglis and her medical staff.

During the First World War Inglis arranged fourteen medical units to serve in France, Serbia, Corsica, Salonika, Romania, Russia and Malta. In August 1916, the London Suffrage Society financed Inglis and eighty women to support Serbian soldiers fighting for the allies. One government official who saw the doctors and nurses working in Russia remarked that: "No wonder England is a great country if the women are like that."

Ishobel Ross recalls visiting the Balkan Front with Ingles in February 1917: "Mrs. Ingles and I went up behind the camp and through the trenches. It was so quiet with just the sound of the wind whistling through the tangles of wire. What a terrible sight it was to see the bodies half buried and all the place strewn with bullets, letter cases, gas masks, empty shells and daggers. We came across a stretch of field telephone too. It took us ages to break up the earth with our spades as the ground was so hard, but we buried as many bodies as we could. We shall have to come back to bury more as it is very tiring work."

In March 1917 Inglis had a disagreement with Evelina Haverfield. She later wrote: "I hope the Committee will realize that though Mrs. Haverfield and I differed over the plans for the future, there isn't a particle of ill-feeling between us. Mrs. Haverfield is as generous and open-minded and as ready to face facts as she always was. All we either of us care about is the success of the unit - and our ideas differ... The Committee must decide between us! - Anyhow they may be thoroughly proud of the work the Transport has accomplished."

Florence Farmborough was one of those who met her while she was serving in Podgaytsy. "There is an English hospital in Podgaytsy, run by a group of English nurses, under the leadership of an English lady-doctor (Dr. Elsie Inglis). I was very glad to chat with them in my mother-tongue and above all to learn the latest news of the allied front in France. They are very nice women, those English and Scottish nurses. They all have several years of training behind them. I feel distinctly raw in comparison, knowing that a mere six-months' course as a VAD in a military hospital would, in England, never have been considered sufficient to graduate to a Front Line Red Cross Unit."

Elsie Inglis was taken ill while in Russia and was forced to travel back to Britain. Inglis, who was suffering from cancer, arrived at Newcastle Upon Tyne on 25th November, 1917, but local doctors were unable to save her and she died the following day. Arthur Balfour, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs commented on her death: "Elsie Inglis was a wonderful compound of enthusiasm, strength of purpose and kindliness. In the history of this World War, alike by what she did and by the heroism, driving power and the simplicity by which she did it, Elsie Inglis has earned an everlasting place of honour."

On this day in 1888 Thomas Edward Lawrence, the illegitimate son of Sir Thomas Chapman (1846–1919), an Anglo-Irish baronet, was born in Tremadoc, Wales on 16th August, 1888. His mother, Sarah Junner (1861–1959), was Chapman's mistress and they assumed the name Lawrence after giving birth to their first child, Robert in 1885.

According to Lawrence James: "Thomas Chapman of South Hill, near Delvin, co. Westmeath, was already married when he began his liaison with Sarah Junner, who was governess to his four daughters. After making a financial settlement on his first family he and Sarah began a peripatetic existence, living successively at Tremadoc, Kirkcudbright, Dinard in Brittany, Langley in Hampshire, and Oxford, where they settled at 2 Polstead Road in 1896. In later years Lawrence liked to present himself as a child brought up in straitened circumstances and engaged in intermittent tussles with his mother. These rows reached such a pitch that he ran away and enlisted in 1905, or so he claimed. No record of his army service or of his father's buying him out has been discovered."

His mother later recalled: "He was a big, strong, active child; constantly on the move. He would pull himself up over the nursery gate some months before he could walk....He was never idle - brass-rubbing, wood-carving, putting old pottery together, etc... He was a most loving son and brother, kind and unselfish, always doing kind deeds in a quiet way; everything that was beautiful in nature or art appealed to him."

It has been claimed that Thomas (Ned to the family) was a "wilful child" who often clashed with his mother. At the age of about ten, he uncovered the truth of his parents' relationship and his own and his brothers' illegitimacy. The conflict with his parents was partly resolved by his father agreeing to build Thomas a well-provided bungalow at the bottom of the garden in 1908. Here he spent his time reading and eventually gained a Meyricke Exhibition to read modern history at Jesus College.

Lawrence was always a fairly small man, just over 5 feet 5 inches tall when he arrived at the University of Cambridge, and liked to boast, that rigorous exercise had turned him into a pocket Hercules. He was a good distance runner, but disliked team games. He became close to the writer, Leonard M. Green. He later recalled: "We decided that we would buy a windmill on a headland that was washed by sea. We would set up a printing press in the lowest storey and live over our shop."

Vyvyan Warren Richards, a fellow undergraduate, fell in love with Lawrence. in his book, Portrait of T.E. Lawrence (1936), Richards wrote: "He had neither flesh nor carnality of any kind; he just did not understand. He received my affection, my sacrifice, in fact, eventually my total subservience, as though it was his due. He never gave the slightest sign that he understood my motives or fathomed my desire... I realize now that he was sexless - at least that he was unaware of sex."

In the summers of 1907 and 1908 his father provided the money for him to undertake extended bicycle tours of France in search of castles. The following year he visited Lebanon and Syria. This research into castles provided the basis of a BA dissertation which substantially contributed to his first-class degree in July 1910. His biographer, Lawrence James, points out: "During all his excursions he wrote home regularly with vivid impressions of what he had seen. These letters are not only evidence of his powers of description, but of the warm affection which existed within his family. Past tensions had evaporated, not least because Lawrence had secured the freedom to live on his own terms and pursue his own interests."

On his return to England he began making plans to establish a publishing business with Vyvyan Warren Richards. His biographer, Desmond Stewart has argued: "Lawrence, for once, sees himself as a businessman. While Richards will have contributed energy, inspiration and design, Lawrence will have put up the capital." Lawrence wrote to his parents: We both feel (at present) that printing is the best thing we can do, if we do it the best we can. That means though (as it is an art), that it will be done only when we feel inclined. Very likely sometimes for long periods I will not touch a press at all. Richards, whose other interests are less militant, will probably do the bulk of the work."

In 1911 Lawrence was recruited by David G. Hogarth of Ashmolean Museum, to join an archaeological expedition led by Sir William Finders Petrie at Carchemish, on the Euphrates. Sir Frederic George Kenyon, the director of the British Museum, wrote that Lawrence was selected because he was "an Arabic scholar, acquainted with the country and an expert on the subject of pottery". As the dig was closed down during the summer months he used this time to explore the area. It also gave him the opportunity to learn to speak numerous Arab dialects.

T. E. Lawrence worked on the archaeological site until early 1914. His biographer, Lawrence James, argues: "As well as supervising the uncovering and cataloguing of Hittite artefacts Lawrence became immersed in the life of a turbulent region. According to his letters home he acted as a sort of consul, arbitrating disputes among Arabs and Kurds and threw himself into their intermittent squabbles with German engineers, then supervising the construction of the Berlin to Baghdad railway. As well as playing the Hentyesque Englishman, Lawrence cultivated an intimate friendship with an Arab youth, Dahoum, whose natural intelligence impressed him and qualified him for tutelage. Lawrence's enchantment with Dahoum helped convince him of the Arabs' capacity for regeneration, but on their own terms and without repudiating their traditions and culture. What he had seen in Lebanon made Lawrence hostile towards those Arabs who looked to the West for salvation and absorbed European, particularly French, values. Likewise, he despised the far-reaching modernizing projects of the Young Turks, who then controlled the Ottoman empire."

During this period he became infatuated with a 14 year old boy, Selim Ahmed (Dahoum). He decided to teach the boy to read and write: "He is beginning to use his reason as well as his instinct: He taught himself to read a little, so I had very exceptional material to work on but I cannot do much with a piece of stick and scrap of dusty ground as materials. I am going to ask Miss Fareedah for a few simple books, amusing, for him to begin on." Leonard Woolley, another member of the team of archaeologists, remembered Dahoum as "not particularly intelligent.... but beautifully built and remarkably handsome." One historian has pointed out: "Lawrence adopted the boy as a semi-permanent companion and trained him up as his archaeological assistant. They went on expeditions together, worked alongside each other, swapped clothes and were rarely apart.... in 1913 and Dahoum moved in with him."

In July 1913 Lawrence brought Dahoum back to Oxford where the two men stayed at the house in the back of the garden. They visited London where Lawrence showed Dahoum the underground railway before travelling back via the Netherlands, Austria and Alexandria. They were back in Aleppo by 24th August. Soon afterwards he carved a naked sculpture of Dahoum. Desmond Stewart has argued that the work of art proved the epicentre of a local scandal... reared in the Muslim suspicion of all representational art, the villagers took Lawrence's sculpture of a naked youth as proof of a guilty passion."

On the outbreak of the First World War Lawrence was forced to leave Dahoum as custodian to the Carchemish site. In December 1914 Lawrence was recruited by army intelligence in North Africa and worked as a junior officer in Egypt. In October 1916 he was sent to meet important Arab leaders such as Faisal ibn Ali and Nuri es-Said in Jiddah. After negotiations it was agreed to help Lawrence to lead an Arab revolt against the Turkish Army. From November 1916 onwards Lawrence was permanently attached to Feisal's forces as a liaison officer, advising on strategy and supervising among other things the procurement of arms and delivery of Treasury subsidies. Lawrence of Arabia, as he became known, carried out raids on the Damascus-Medina Railway. His men also captured the port of Aqaba in July 1917. Sympathetic to Arab nationalism he helped established local government in captured towns.

In November 1917 Lawrence led a raiding party in southern Syria to harry Turkish communications and to stir up local opposition to France. He was captured in Deraa and identified by a Turkish officer. According to Lawrence he was led to a guard-room, consoled by Turkish soldiers and told he will be released next day "if he fulfils the Bey's pleasures". Lawrence was then taken to the bedroom of Bey (the governor of Hajjim). He has him stripped and has him punished by a Circassian riding whip, described by Lawrence as "a thong of supple black hide, rounded, and tapering from the thickness of a thumb at the grip (which was wrapped in silver) down to a hard point finer than a pencil." Held down by four soldiers, he was then whipped: "At the instant of each stroke a hard white mark like a railway, darkening slowly into crimson, leaped over my skin, and a bead of blood swelled up wherever the ridges crossed... the blows hurt more horribly than I had dreamed of... a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me." Lawrence then suffered homosexual rape. He later told Charlotte Shaw: "About that night. I shouldn't tell you, because decent men don't talk about such things. I wanted to put it plain in the book (his autobiography), and wrestled for days with my self-respect... which wouldn't, hasn't let me."

T. E. Lawrence claims that the "corporal... the youngest and best looking on the guard had to stay behind while the others carried me down the narrow stairs". The soldier then tells him "that the door into the next room was not locked". In the room hangs a "suit of shoddy clothes". Next morning Lawrence puts them on and escapes back to the British forces. Some biographers, have refused to believe this story. This included Richard Aldington, the author of Lawrence of Arabia: a Biographical Enquiry (1955). According to Lawrence James: "Aldington began his researches with an open mind, but as he trawled through the available sources he found abundant evidence of contradictions, inconsistencies, and fabrications.... Lawrence's defenders insisted that Aldington was not only traducing a national hero, but the values he and his generation had stood for."

By December, 1917 Edmund Allenby and his army had captured Beersheba, Gaza and Jerusalem. The following year the British Army defeated General Otto Liman von Sanders and the Turkish-German Army in Palestine. Lawrence now joined Allenby's forces and entered Damascus on 1st October, 1918.

Lawrence attended Paris Peace Conference with Prince Feisal. He had meetings with Felix Frankfurter. His assistant, Ella Winter, recalled in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "The young, beautiful Prince Feisal was always followed by his group of tall, imposing, silent Arabs in long white robes and head dress, and by his shadow, Colonel T. E. Lawrence, also in native dress. Lawrence was short and fragile-looking, with a delicate, poetic face, but he appeared as much at home with the desert Bedouins and the prince he seemed so attached to as with European diplomats. Felix was as much intrigued by Lawrence's role in all the Middle Eastern politics as with his romantic appearance."

Lawrence had been converted to the cause of the Arabs and felt they were betrayed by the treaties agreed at the Paris Peace Conference. He was particularly concerned about the decision to give France control over Syria. He later wrote: "We lived many lives in those whirling campaigns, never sparing ourselves: yet when we achieved and the new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to remake in the likeness of the former world they knew."

In 1921 Lawrence joined the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office. He also served as special adviser on Arab affairs to Winston Churchill, the Colonial Secretary (1921-22). Both men visited the Middle East in an attempt to deal with the growing conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine.

After leaving the Colonial Office he changed his name to John Hume Ross and enlisted into the Royal Air Force. After four months reporters from the Daily Express discovered what he had done and he was discharged. In March 1923 he joined the Tank Corps as Private Thomas Shaw. Lawrence became sexually involved with John Bruce. He later told the authors of The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia (1969) that Lawrence paid him a regular retainer of £3 a week to birch him on his bare buttocks.

Lawrence served until he was dismissed from the service in 1925. This was partly because he had developed a relationship with a young soldier, R.A.M. Guy, who was described as being "beautiful, like a Greek god." According to Desmond Stewart, the author of T. E. Lawrence (1979), Lawrence dismissed because he was about to be exposed as being involved in a sexual scandal: "Lawrence had unwisely attended flagellation parties in Chelsea conducted by an underworld figure known as Bluebeard, and Bluebeard's impending divorce case threatened to release lubricious details concerning Lawrence and one of his aristocratic friends which had already been hinted at in a German scandal-sheet.... Sacrificing caution, he wrote to the Home Secretary asking for the expulsion of Bluebeard and a ban on the German magazine."

Lawrence purchased Clouds Hill in 1924 and began work on his autobiography. The Seven Pillars of Wisdom was published privately in 1926. It included illustrations by his friend, Eric Kennington. Later that year he rejoined the RAF and served for two years on the north-west frontier of India. He continued to write and other books by Lawrence include Revolt in the Desert, The Mint and a new translation of Homer's Odyssey.

On 26th February 1935 Lawrence left the RAF. Soon afterwards he was contacted by Henry Williamson, a member of the British Union of Fascists, suggesting a meeting that "might prevent another war". Williamson later recalled that he obtained "Lawrence of Arabia's name to gather a meeting of ex-Service men in the Albert Hall, with his presence and stimulation to cohere into unassailable logic the authentic mind of the war generation come to power of truth and amity, a whirlwind campaign which would end the old fearful thought of Europe (usuary-based) for-ever. So that the sun should shine on free men."

Lawrence held very nationalistic views. He had said of his experiences in the First World War: "I am proudest of my thirty fights in that I did not have any of our own blood shed. All our subject provinces to me were not worth one dead Englishman." E. M. Forster once said that Lawrence "hated war but liked soldiers". Lawrence also expressed racist views about black people in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom: "Their faces, being clearly different from our own, were tolerable; but it hurt that they should possess exact counterparts of all our bodies."

Lawrence loved riding his motor-bike. George Brough, who manufactured his bikes, described him as: "One of the finest riders I have ever met. In the several runs I took with him, I am able to state with conviction that T.E.L. was most considerate to every other road user. I never saw him take a single risk nor put any other rider or driver to the slightest inconvenience."

On 13th May, he went for a ride on his Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle when he swerved to miss two 14 year-old, cyclists, Frank Fletcher and Albert Hargreaves. Corporal Ernest Catchpole of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, was the first to reach the site of the accident. He later claimed that he was passed by a black motor car just before the crash: "I saw the bike twisting and turning over and over along the road. I saw nothing of the driver (of the black car). I ran to the scene and found the motor-cyclist on the road. His face was covered with blood which I tried to wipe away with my handkerchief". Lawrence never regained consciousness and died on 19th May 1935.

Desmond Stewart has argued: "Bovington Camp reacted to this as something more than an ordinary traffic accident. All ranks were warned that they came under the Official Secrets Act. The boys' fathers were told to keep them silent. Catchpole was cautioned that, since he had not seen the accident, he should not confuse matters by mentioning the black car. Two plain clothes detectives were posted on Lawrence duty: one sat by his bed, while the other rested on a cot outside the door... His brother, Arnold Lawrence, returned from a holiday in Spain to hear reports that officials from the Air Ministry had removed secret papers from Clouds Hill." Arnold Lawrence later told the Dorset Daily Echo that a "special guard" had been sent to Clouds Hill to "protect my brother's valuable books".

Frank Fletcher told a reporter of a local newspaper: "We were riding in single file. I was leading.... I heard the noise of the motorcycle and then the crash.... The man who had gone over the handle bars had landed with his feet about 5 yards in front of the motor cycle which was about five yards ahead of where I fell." According to the newspaper: "The boy said there was no motor car or other vehicle on the road at the time.

After his death rumours circulated that Lawrence had been murdered by foreign agents. Desmond Stewart believes that Catchpole's evidence is of vital importance and that the black car was involved in the death of Lawrence. "If Catchpole was right and the black car existed, the failure of its driver to come forward (the news of the accident was in every newspaper and every news bulletin) suggests that he was involved, either accidentally or deliberately, in Lawrence's crash. Everyone who has ridden a motor cycle knows how easily a sudden swerve can be induced; harmless to the driver of a car, on a narrow road it could be fatal to a cyclist without a helmet."

Another story emerged that the secret service faked his death so as to allow him to undertake, incognito, important work in the Middle East. The supporters of this story believed he died in Tangiers, Morocco, in 1968.

On this day in 1912 Ted Drake was born in Southampton. After leaving school he worked as gas-meter reader.

A talented footballer he played for Southampton Gasworks and Winchester City before joining Southampton. He scored a hat-trick on his debut against Swansea Town on 14th November 1931.

In the 1932-33 season Drake scored 20 goals in 33 games. Herbert Chapman, the manager of Arsenal, tried to sign Drake but he rejected a move to London as he was happy playing for George Kay. The following season Drake was the Second Division's top goalscorer.

George Allison, the new manager of Arsenal, made another attempt to sign Drake in March 1934. Southampton had financial problems at the time and agreed a fee of £6,500 for their star centre-forward. While at the club he had scored 48 goals in 74 appearances.

Drake scored a goal on his debut for Arsenal against Wolverhampton Wanderers on 24th March, 1934. Arsenal won the First Division league championship that season but Drake joined too late to qualify for a medal.

Ted Drake scored 42 goals in 41 games in the 1934-35 season. This included three hat-tricks against Liverpool, Tottenham Hotspur and Leicester City and four, four-goal hauls, against Birmingham City, Chelsea, Wolves and Middlesbrough. These goals helped Arsenal to win the league championship.

Drake won his first international cap for England against Italy on 14th November 1934. The England team that day also included Eddie Hapgood, Ray Bowden, Wilf Copping, Cliff Bastin, George Male, Frank Moss, Stanley Matthews and Eric Brook. Drake scored one of the goals in England's 3-2 victory.

The following season Drake played in England's 2-1 victory over Northern Ireland. Drake had a particularly good game against Aston Villa on 14th December, 1935. He was suffering from a knee injury but George Allison decided to risk him. By half-time he had scored a hat-trick. Drake scored three more in the first 15 minutes of the second-half. Drake then hit the bar and when he told the referee it had crossed the line, he replied: "Don't be greedy, isn't six enough". In the last minute he converted a cross from Cliff Bastin. Seven goals in an away game was an amazing achievement.

Ted Drake returned to the England team against Wales on 5th February 1936. He failed to score and was replaced by George Camsell in the next game against Scotland. Freddie Steele also played in this position until Drake regained his place in the game against Hungary on 2nd December 1936. Drake rewarded the selectors with a hat-trick in the 6-2 victory.

However, a serious knee injury, that needed a cartilage operation, put Drake out of action for ten weeks. Arsenal missed his goals and only finished in 6th place behind Sunderland. Arsenal did much better in the FA Cup that season. Arsenal beat Liverpool (2-0), Newcastle United (3-0), Barnsley (4-1) and Grimsby Town (1-0) to reach the final against Sheffield United.

As Eddie Hapgood pointed out: The match will go down in history as Ted Drake's Final. Badly injured in the Welsh match at Wolverhampton three months before (when, incidentally, Arsenal had six men chosen), Ted was gambled on at Wembley. And the gamble came off. Wearing the world's biggest bandage on his left knee, Ted got the only goal of the match sixteen minutes from time. He told us in the dressing-room that when he received Cliff Bastin's pass, he knew it was now or never. And that when he hit the ball he knew it was a goal."

Some of Arsenal's key players such as Alex James, Cliff Bastin, Joe Hume, Ray John and Herbert Roberts were past their best. Drake and Ray Bowden continued to suffer from injuries, whereas Frank Moss was forced to retire from the game with a shoulder injury. Given these problems Arsenal did well to finish in 3rd place in the 1936-37 season.

Before the start of the 1937-38 season Herbert Roberts, Ray John and Alex James retired from football. Joe Hume was out with a long-term back injury and Ray Bowden was sold to Newcastle United. However, a new group of younger players such as Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen and Leslie Compton, became regulars in the side. George Hunt was also bought from Tottenham Hotspur to provide cover for Ted Drake who was still suffering from a knee injury. Cliff Bastin and George Male were now the only survivors of the team managed by Herbert Chapman.

Wolves were expected to be Arsenal's main rivals in the 1937-38 season. However, it was Brentford who led the table in February. They also beat Arsenal on 18th April, a game in which Ted Drake broke his wrist and suffered a bad head wound. However, it was the only two points they won during a eight game period and gradually dropped out of contention.

On the last day of the season Wolves were away to Sunderland. If Wolves won the game they would be champions, but they drew 1-1. Arsenal beat Bolton Wanderers at Highbury and won their fifth title in eight years. As a result of his many injuries, Ted Drake only played in 28 games but he still ended up the club's top scorer with 17 goals.

Jeff Harris, the author of Arsenal Who's Who argues that "Drake's main attributes were his powerful dashing runs, his great strength combined with terrific speed and a powerful shot. Ted Drake was also brilliant in the air but above all, so unbelievably fearless."

Stan Mortensen considered Drake a better centre-forward than Tommy Lawton: "I came to regard him as my ideal centre-forward... Drake was absolutely fearless. I do not mean that he threw his weight about to hurt other players. He would risk physical injury to himself if he could see half a chance - no, one tenth of a chance - to get through to score.... I am afraid his method similarly took toll of his frame. But he never eased up, and was completely unselfish, always on the look-out for a chance to make an opening for the inside-forwards.

Drake also scored two of the goals in England's 4-2 victory over France on 26th May 1938. Stanley Matthews, who played for England that day later recalled: "Ted Drake turned in a masterful performance. He hurled himself around in the French penalty area, his robust, barnstorming style always a source of trouble to France, and he ended the game with two goals to his name. We ran out comfortable 4-2 winners with our other goals coming from Frank Broome and Cliff Bastin." Drake had scored six goals in five games but it was the last time he played for his country.

The outbreak of the Second World War brought a halt to Ted Drake's Arsenal career. Despite his many injuries he was Arsenal's leading league goalscorer in each of his five seasons at the club.

Drake served in the Royal Air Force during the war and managed to score 86 goals in 128 friendly games for Arsenal. In a game against Reading in 1945 Drake suffered a serious spinal injury and was forced to retire from the game. During his first-class football career he had scored 171 goals in 238 appearances.

Drake became manager of Reading in 1947. At the time the club was playing in the Third Division and in the 1951-52 season the club finished in second place in the league. As a result of this Drake was appointed manager of Chelsea. The club won the First Division championship in the 1954-55 season. In doing so, he became the first person to win the league title both as player and manager. Unfortunately the team went into decline and Drake was sacked in 1962.

Ted Drake died on 30th May 1995.