On this day on 13th April

On this day in 1570 Guy Fawkes, the only son of a Edward Fawkes and his wife, Edith Jackson, was born in York in 1570. Fawkes father was a proctor of the ecclesiastical courts and advocate of the consistory court of the Archbishop of York, and a staunch Protestant. His mother's family were recusant Catholics, and his cousin, Richard Cowling, became a Jesuit priest.

Edward Fawkes died in January, 1579, and three years later his widow married Denis Bainbridge of Scotton, a Roman Catholic. Fawkes was educated at St Peter's School in York. Also at the school was John Wright and Christopher Wright. The headmaster, John Pulleyn, came from a family of noted Yorkshire recusants. It is claimed that the three boys were greatly influenced by being taught about the way Henry VIII had persecuted religious dissents.

In 1592 Guy Fawkes married Maria Pulleyn. He sold the small estate in Clifton which he had inherited from his father and went to fight for the armies of Catholic Spain in the Low Countries. He was described as conscientious and brave and behaved gallantly at the siege of Calais in 1596. A close friend described him as being a devout Catholic who was "pleasant of approach and cheerful of manner, opposed to quarrels and strife… loyal to his friends, but... a man highly skilled in matters of war". Later he travelled to Spain in an attempt to persuade the king to send Catholic troops to invade England.

Queen Elizabeth died on 24th March, 1603. Later that day, Robert Cecil, read out the proclamation announcing James VI of Scotland as the next king of England. The following day the new king wrote from Edinburgh informally confirming all the privy council in their positions, adding in his own hand to Cecil, "How happy I think myself by the conquest of so wise a councillor I reserve it to be expressed out of my own mouth unto you".

James left for England on 26th March 1603. When he arrived at York his first act was to write to the English Privy Council for money as he was deeply in debt. His demands were agreed as they were anxious to develop a good relationship with their king who looked like a promising new leader. "James's quick brain, his aptitude for business, his willingness to take decisions, right or wrong, were welcome enough after Elizabeth's tedious procrastination over trifles. They were charmed, too, by his informal bonhomie."

Soon after arriving in London, King James told Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, "as for the catholics, I will neither persecute any that will be quiet and give but an outward obedience to the law, neither will I spare to advance any of them that will by good service worthily deserve it." James kept his promise and the catholics enjoyed a degree of tolerance that they had not known for a long time. Catholics now became more open about their religious beliefs and this resulted in accusations that James was not a committed Protestant. (8) The king responded by ordering in February 1605, the reintroduction of the penal laws against the catholics. It has been estimated that 5,560 people were convicted of rucusancy during this period.

Roman Catholics felt bitter by what they saw as the king's betrayal. They now realised that they were an isolated minority in a hostile community. In February 1604, Robert Catesby devised the Gunpowder Plot, a scheme to kill King James and as many Members of Parliament as possible. Catesby recruited Thomas Wintour and in April 1604, he introduced him to Guy Fawkes.

At a meeting at the Duck and Drake Inn on 20th May, Catesby explained his plan to Guy Fawkes, Thomas Wintour, Thomas Percy and John Wright. All the men agreed under oath to join the conspiracy. Over the next few months Francis Tresham, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates and Christopher Wright also agreed to take part in the overthrow of the king.

Catesby's plan involved blowing up the Houses of Parliament on 5th November, 1605. This date was chosen because the king was due to open Parliament on that day. At first the group tried to tunnel under Parliament. This plan changed when Thomas Percy was able to hire a cellar under the House of Lords. The plotters then filled the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The conspirators also hoped to kidnap the king's daughter, Elizabeth. In time, Catesby was going to arrange Elizabeth's marriage to a Catholic nobleman.

One of the people involved in the plot was Francis Tresham. He was worried that the explosion would kill his friend and brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. On 26th October, Tresham sent Lord Monteagle a letter warning him not to attend Parliament on 5th November. Monteagle became suspicious and passed the letter to Robert Cecil. Cecil quickly organised a thorough search of the Houses of Parliament.

While searching the cellars below the House of Lords, Sir Thomas Knyvett, keeper of the Palace of Westminster, and his men found Guy Fawkes, who claimed he was John Johnson, the servant of Thomas Percy. He was arrested, and when his men hauled away the faggots and brushwood, they uncovered thirty-six barrels - nearly a ton - of gunpowder.

Guy Fawkes was tortured and admitted that he was part of a plot to "blow the Scotsman (James) back to Scotland". On the 7th November, after enduring further tortures, Fawkes gave the names of his fellow conspirators. "Catesby suggested... making a mine under the upper house of Parliament... because religion had been unjustly suppressed there... twenty barrels of gunpowder were moved to the cellar... It was agreed to seize Lady Elizabeth, the king's eldest daughter... and to proclaim her Queen".

The trial began on the 27th January, 1606. The Attorney-General Sir Edward Coke made a long speech, that included a denial that the King had ever made any promises to the Catholics. He then read out the confessions of the men accused of the crime. Thomas Wintour made a statement where he admitted his involvement but pleaded that his brother, Robert Wintour, should be spared. Everard Digby pleaded guilty, but justified his actions by claiming that the insisting that the King had reneged upon promises of toleration for Catholics.

On 30th January, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Thomas Bates, were tied to hurdles and dragged through the crowded streets of London to St Paul's Churchyard. Digby, the first to mount the scaffold, asked the spectators for forgiveness, and refused the attentions of a Protestant clergyman. He was stripped of his clothing, and wearing only a shirt, climbed the ladder to place his head through the noose. He was quickly cut down, and while still fully conscious was castrated, disembowelled, and then quartered, along with the three other prisoners.

The following day, Thomas Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, Robert Keyes, and Guy Fawkes were taken to the Old Palace Yard at Westminster to be hanged from the gallows, then drawn and quartered in public. A contemporary described Fawkes on the gallows: "Last of all came the great devil of all, Guy Fawkes, who should have put fire to the powder. His body being weak with the torture and sickness he was scarce able to go up the ladder, yet with much ado, by the help of the hangman, went high enough to break his neck by the fall."

According to Camilla Turner he did not die in the way that was expected: "As he awaited his grisly punishment on the gallows, Fawkes leapt to his death - to avoid the horrors of having his testicles cut off, his stomach opened and his guts spilled out before his eyes. He died from a broken neck." His body was subsequently quartered, and his remains were sent to "the four corners of the kingdom" as a warning to others.

This is the traditional story of the Gunpowder Plot. However, in recent years some historians have begun to question this version of events. Some have argued that the plot was really devised by Sir Robert Cecil. This version claims that Cecil blackmailed Catesby into organising the plot. It is argued hat Cecil's aim was to make people in England hate Catholics. For example, people were so angry after they found out about the plot, that they agreed to Cecil's plans to pass a series of laws persecuting Catholics.

Cecil's biographer, Pauline Croft, has argued that this is unlikely to have been true: "In the inflamed atmosphere after November 1605, with wild accusations and counter-accusations being traded by religious polemicists, there were allegations that Cecil himself had devised the Gunpowder Plot to elevate his own importance in the eyes of the king, and to facilitate a further attack on the Jesuits. Numerous subsequent efforts to substantiate these conspiracy theories have all failed abysmally."

Robert Cecil definitely took advantage of the situation. Henry Garnett, head of the Jesuit mission in England, was arrested. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out: "The evidence against him was largely circumstantial, but the government was determined to tar all the missionary priests with the brush of sedition in the hope of thereby depriving them of the support of the lay catholic community. A further step in this direction came in 1606, with the drawing up of an oath of allegiance which all catholics were required to take."

The failed Gunpowder Plot united the nation. The anniversary of 5th November became an annual holiday. In the Parliament that followed the conspiracy James obtained a vote of subsidies and other levies amounting to about £450,000. In April, 1606, James managed to persuade Parliament to accept that the newly designed Union Jack flag would be flown on British ships. English ships would continue to fly the St George's cross, whereas Scottish ones would still use the St Andrew flag.

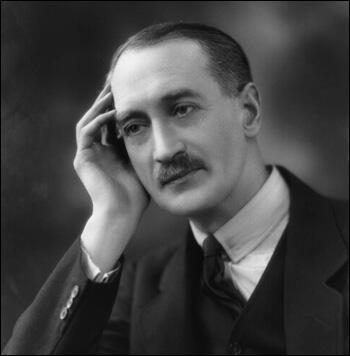

On this day in 1769 Thomas Lawrence, the son of an innkeeper, was born in Bristol on 13th April 1769. He developed a reputation for painting portraits as a child and by the age of twelve had his own studio in Bath.

In 1787 he became a student at the Royal Academy and two years later, at the age of twenty, he was asked to paint Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III. The king was pleased with the portrait and on the death of Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1792, he appointed Lawrence as the royal painter.

Lawrence was knighted in 1815 and five years later became president of the Royal Academy. Although Lawrence was a very popular painter who could command high fees for his work, he was often heavily in debt. Lawrence painting the portraits of many leading politicians including Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, Sir Francis Burdett and William Wilberforce. Sir Thomas Lawrence died on 7th January 1830.

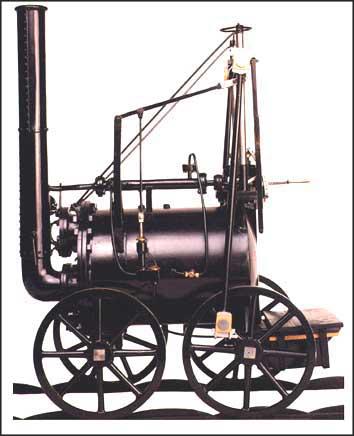

On this day in 1771 Richard Trevithick was born in Illogan, Cornwall, in 1771. Richard was educated at Camborne School but he was more interested in sport than academic learning. Trevithick was six feet two inches high and was known as the Cornish giant. He was very strong lad and by the age of eighteen he could throw sledge hammers over the tops of engine houses and write his name on a beam six feet from the floor with half a hundredweight hanging from his thumb. Trevithick also had the reputation of being one of the best wrestlers in Cornwall.

Trevithick went to work with his father at Wheal Treasury mine and soon revealed an aptitude for engineering. After making improvements to the Bull Steam Engine, Trevithick was promoted to engineer of the Ding Dong mine at Penzance. While at the Ding Dong mine he developed a successful high-pressure engine that was soon in great demand in Cornwall and South Wales for raising the ore and refuse from mines.

Trevithick also began experimenting with the idea of producing a steam locomotive. At first he concentrating on making a miniature locomotive and by 1796 had produced one that worked. The boiler and engine were in one piece; hot water was put into the boiler and a redhot iron was inserted into a tube underneath; thus causing steam to be raised and the engine set in motion.

Richard Trevithick now attempted to produce a much larger steam road locomotive and on Christmas Eve, 1801, it used it to take seven friends on a short journey. The locomotive's principle features were a cylindrical horizontal boiler and a single horizontal cylinder let into it. The piston, propelled back and forth in the cylinder by pressure of steam, was linked by piston rod and connecting rod to a crankshaft bearing a large flywheel. Trevithick's locomotive became known as the Puffing Devil but it could only go on short journeys as he was unable to find a way of keeping up the steam for any length of time.

Despite these early problems, Trevithick travelled to London where he showed several leading scientists, including Humphrey Davy, what he had invented. James Watt had been considering using this method to power a locomotive but had rejected the idea as too risky. Watt argued that the use of steam at high temperature, would result in dangerous explosions. Trevithick was later to accuse Watt and his partner, Matthew Boulton, of using their influence to persuade Parliament to pass a bill banning his experiments with steam locomotives.

In 1803 a company called Vivian & West, agreed to finance Trevithick's experiments. Richard Trevithick exhibited his new locomotive in London. However, after a couple of days the locomotive encountered serious problems that prevented it pulling a carriage. Vivian & West were disappointed with Trevithick's lack of practical success and they withdrew from the project.

Richard Trevithick soon found another sponsor in Samuel Homfray, the owner of the Penydarren Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil. In February 1804, Trevithick produced the world's first steam engine to run successfully on rails. The locomotive, with its single vertical cylinder, 8 foot flywheel and long piston-rod, managed to haul ten tons of iron, seventy passengers and five wagons from the ironworks at Penydarren to the Merthyr-Cardiff Canal. During the nine mile journey the Penydarren locomotive reached speeds of nearly five miles an hour. Trevithick's locomotive employed the very important principle of turning the exhaust steam up the chimney, so producing a draft which drew the hot gases from the fire more powerfully through the boiler.

Trevithick's Penydarren locomotive only made three journeys. Each time the seven-ton steam engine broke the cast iron rails. Samuel Homfray came to the conclusion that Trevithick's invention was unlikely to reduce his transport costs and so he decided to abandon the project.

Trevithick was now employed by Christopher Blackett, who owned the Wylam Colliery in Northumberland. A five-mile wooden wagonway had been built in 1748 to take the coal from Wylam to the River Tyne. Blackett wanted a locomotive that would replace the use of horse-drawn coal wagons. The Wylam locomotive was built but weighing five tons, it was too heavy for Blackett's wooden wagonway.

Trevithick returned to Cornwall and after further experiments developed a new locomotive he called Catch Me Who Can. In the summer of 1808 Trevithick erected a circular railway in Euston Square and during the months of July and August people could ride on his locomotive on the payment of one shilling. Trevithick had plenty of volunteers for his locomotive that reached speeds of 12 mph (19 kph) but once again the rails broke and he was forced to bring the experiment to an end.

Without financial backing, Richard Trevithick had to abandon his plans to develop a steam locomotive. Trevithick now found work with a company who paid him to develop a steam dredger to lift waste from the bottom of the Thames. He was paid by results, receiving sixpence for every ton lifted from the river.

Richard Trevithick found it difficult to make money from his steam dredger and in 1816 he accepted an offer to work as an engineer in a silver mine in Peru. After some early difficulties, Trevithick's steam-engines were very successful and he was able to use his profits to acquire his own silver mines. However, in 1826 war broke out and Trevithick was forced to flee and leave behind his steam-engines and silver mines. After a unsuccessful spell in Costa Rica, Trevithick moved to Colombia, where he met Robert Stephenson, who was building a railway in that country. Stephenson generously gave Trevithick the money to pay for his journey back to England.

Although inventors such as George Stephenson argued that Trevithick's early experiments were vital to the development of locomotives, in February 1828, the House of Commons rejected a petition suggesting that he should receive a government pension. Trevithick continued to experiment with new ideas. This included the propulsion of steamboats by means of a spiral wheel at the stern, an improved marine boiler, a new recoil gun-carriage and apparatus for heating apartments. Another scheme was the building of a 1,000 feet cast-iron column to commemorate the 1832 Reform Act.

All these schemes failed to receive financial support and Richard Trevithick died in extreme poverty at the Bull Inn, Dartford, on 22nd April, 1833. As he left no money for his burial, he faced the prospect of a pauper's funeral. However, when a group of local factory workers heard the news, they raised enough money to provide a decent funeral and he was buried in Dartford churchyard.

On this day in 1828 Josephine Butler, the daughter of John Grey and Hannah Annett, was born on 13th April 1828. Grey was a wealthy landowner and the cousin of Earl Grey, the British Prime Minister who led the Whig administration between 1830 and 1834. Her father was a strong advocate of social reform and played a significant role in the campaign for the 1832 Reform Act and the repeal of the Corn Laws. Josephine grew up to share her father's religious and moral principles and his strong dislike of inequality and injustice.

Josephine was an attractive woman and Prince Leopold claimed that she was "considered by many people to be the most beautiful woman in the world." In 1852 Josephine married George Butler, an examiner of schools in Oxford. In the first five years of marriage Josephine had four children. In 1857 the couple moved from Oxford after George Butler was appointed vice-principal of Cheltenham College. George and Josephine had similar political views and during the American Civil War they encountered a great deal of hostility in Cheltenham when they expressed their support for the anti-slavery movement.

In 1863, Eva, Josephine's only daughter, fell to her death in front of her. Josephine was devastated by the death of her six year-old daughter and was never to fully recover from this family tragedy. In an attempt to cope with her grief, Josephine Butler became involved in charity work. This involved Josephine visiting the local workhouse and rescuing young prostitutes from the streets.

Josephine also began to take a keen interest in women's education. In 1867 she joined Anne Jemima Clough in establishing courses of advanced study for women. Later that year Josephine Butler was appointed president of the North of England Council for the Higher Education of Women. The following year Josephine became involved in the campaign to persuade Cambridge University to provide more opportunities for women students. This campaign resulted in the provision of lectures for women and later the establishment of Newnham College.

In 1868 Josephine Butler published her book The Education and Employment of Women. In her pamphlet, she argued for improved educational and employment opportunities for single women. The following year she wrote Women's Work and Women's Culture, in which she argued that women should not "try to rival men since they had a different part to play in society". These views upset some feminists such as Emily Davies who wanted women to compete on the same terms as men. Butler believed that women should have the vote because they were different from men. She argued that women's special role was to protect and care for the weak and that women's suffrage was of vital importance to the morality and welfare of the nation.

In 1869 Josephine Butler began her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Act. These acts had been introduced in the 1860s in an attempt to reduce venereal disease in the armed forces. Butler objected in principal to laws that only applied to women. Under the terms of these acts, the police could arrest women they believed were prostitutes and could then insist that they had a medical examination. Butler had considerable sympathy for the plight of prostitutes who she believed had been forced into this work by low earnings and unemployment.

Josephine Butler toured the country making speeches criticizing the Contagious Diseases Acts. Butler, who was an outstanding orator, attracted large audiences to hear her explain why these laws needed to be repealed. Many people were shocked by the idea of a woman speaking in public about sexual matters. George Butler, who was now principal of Liverpool College, was severely criticised for allowing his wife to become involved in this campaign. Butler continued to support his wife in her work despite the warnings that it would damage his academic career.

Butler also became involved in the campaign against child prostitution. In 1885 Butler joined together with Florence Booth of the Salvation Army and W. T. Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, to expose what had become known as the white slave traffic. The group used the case of Eliza Armstrong, a thirteen year-old daughter of a chimney-sweep, who was bought for £5 by a woman working for a London brothel. As a result of the publicity that the Armstrong case generated, Parliament passed the Criminal Law Amendment Act that raised the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen.

After the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act in 1886, Josephine spent her time nursing her sick husband. After his death in 1890, Josephine wrote Recollections of George Butler (1892) and Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade (1896). In her last few years of her life, Josephine became a supporter of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. However, now in her seventies, Josephine was too old to take a prominent role in the movement's activities.

Josephine Butler died on 30th December 1906.

On this day in 1829 legislation is passed that gives Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom the right to vote and to sit in Parliament. In the 18th century attempts were made to obtain full political and civil liberties to British and Irish Roman Catholics. In Ireland, where the majority of the population were Catholics, the Relief Act of 1793 gave them the right to vote in elections, but not to sit in Parliament.

In England the leading campaigners for Catholic emancipation were the Radical members of the House of Commons, Sir Francis Burdett and Joseph Hume.

By the beginning of the 19th century, William Pitt, the leader of Tories, became converted to the idea of Catholic emancipation. Pitt and his Irish Secretary, Lord Castlereagh, promised the Irish Parliament that Catholics would have equality with Protestants when it agreed to the Act of Union in 1801. When King George III refused to accept the idea of religious equality, Pitt and Castlereagh resigned from office.

In 1823 Daniel O'Connell founded the Catholic Association to campaign for the removal of discrimination against Catholics. In 1828 he was elected as M.P. for County Clare but as a Catholic he was not allowed to take his seat in the House of Commons. To avoid the risk of an uprising in Ireland, the British Parliament passed the Roman Catholic Relief Act in 1829, which granted Catholic emancipation and enabled O'Connell to take his seat.

Daniel O'Connell celebrating Catholic Emancipation (1829)

On this day in 1832 David Bywater was interviewed by Michael Sadler and his House of Commons Committee on child labour. Bywater was born in Leeds in 1815. He explained how long he had to work: "We started at one o'clock on Monday morning, and then we went on again till eight o'clock, at breakfast time; then we had half an hour; and then we went on till twelve o'clock, and had half an hour for drinking; and then we stopped at half past eleven for refreshment for an hour and a half at midnight; and then we went on again till breakfast time, when we had half an hour; and then we went on again till twelve o'clock, at dinner time, and then we had an hour: and then we stopped at five o'clock again on Tuesday afternoon for half an hour for drinking; then we went on till past eleven, and then we gave over till five o'clock on Wednesday morning." Bywater claimed that this led to physical deformities: "It made me very crooked in my knees."

Edward Baines' book The History of the Cotton Manufacture (1835)

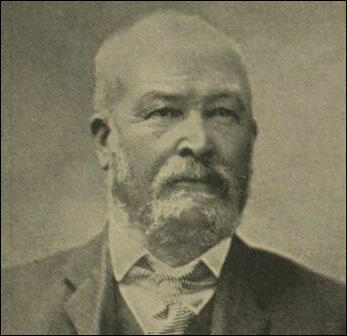

On this day in 1840 Henry Broadhurst, the son of a stonemason, was born at Littlemore. After a brief schooling he started work at the age of twelve. A brief spell as a gardener was followed by an apprenticeship as a stonemason in Oxford. A staunch Methodist, Broadhurst's work mainly involved repairing and enlarging churches and university colleges.

In the late 1850s Broadhurst moved to Norwich where he found work as a stonemason. In 1865 Broadhurst and his new wife, Eliza Olley, moved to London where he was involved in rebuilding the House of Commons.

While in London Broadhurst became involved the struggle for universal suffrage. He joined the Reform League and took part in several demonstrations and meetings in the build up to the passing of the 1867 Reform Act.

In 1872 Henry Broadhurst took part in the campaign to reduce the working week and an increase in the hourly wage paid in the building industry. Broadhurst soon emerged as one of the leaders of the stonemasons and took part in the negotiations with the employers. Broadhurst now gave up his work as a stonemason to become a full-time union official. Later that year Broadhurst represented the Stonemasons Union at the annual Trade Union Congress (TUC) and was elected to its Parliamentary Committee.

In 1873 Broadhurst was elected secretary of the Labour Representation League, an organisation that was attempting to enable working men to be elected to the House of Commons. The LBR sponsored thirteen trade union candidates in the 1874 General Election, and two of them, Alexander MacDonald and Thomas Burt, were elected as Lib-Labs MPs.

Broadhurst played an important role in the campaign to have the Masters and Servants Act repealed and in 1875 the Conservative government, led by Benjamin Disraeli, agreed to the TUC's proposals. As a result of the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act was passed by Parliament in 1875, which secured the right to participate in peaceful picketing.

The following year Henry Broadhurst supported William Gladstone and his campaign against Bulgarian Atrocities. Broadhurst obtained the signatures of over 15,000 people, including many trade union leaders, to a petition which John Bright presented to Parliament.

In the 1880 General Election Broadhurst was elected as Liberal MP for Stoke-upon-Trent. Broadhurst joined Alexander MacDonald and Thomas Burt as Lib-Lab supporters of Gladstone's government. In the House of Commons Broadhurst led the campaign for a government commission to investigate working-class housing. In the 1885 General Election Broadhurst was elected for the Bordesley seat in Birmingham.

After the election, William Gladstone offered Broadhurst the post of Under-Secretary at the Home Office. When Broadhurst accepted the post he became the first working man to become a government minister. Broadhurst's loyal support of the Liberal government upset some trade union leaders. When Broadhurst argued against the eight-hour day, James Keir Hardie remarked that the minister was more Liberal than Labour.

At the 1889 Trade Union Congress Hardie argued that Henry Broadhurst was guilty of holding shares in a company that treated its workers badly. The following year, the TUC supported Hardie against Broadhurst by passing a resolution in favour of the eight-hour day. Broadhurst was especially hurt when he discovered that the Stonemasons Union had voted against him. In the 1892 General Election Broadhurst was defeated at West Nottingham. His objection to the eight-hour day had lost him the support of local workers and this enabled a local colliery owner to defeat him.

Henry Broadhurst was opposed to women's suffrage. A young Beatrice Webb met him in September 1889: "He chatted on about socialism, trade unionism and his own complaints and showed every sign of being confidential. A commonplace person, hard-working no doubt, but a middle-class philistine to the backbone, appealing to the practical shrewdness and the high-flown but mediocre sentiments of the comfortably off working man. His view of women is typical of all his other views: he lives in platitudes and commonplaces."

Attempts to be elected in Grimsey in 1893 ended in failure but Broadhurst eventually won at Leicester in 1894. He held the seat until his retirement before the 1906 General Election.

Henry Broadhurst died at Cromer, Norfolk, on 11th October, 1911.

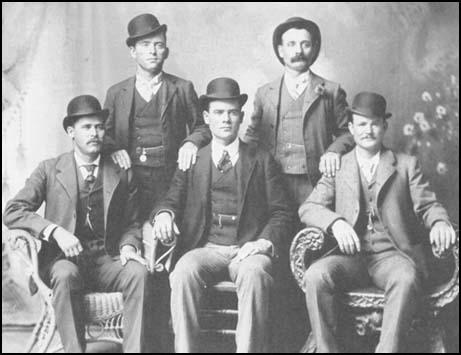

On this day in 1866 Robert LeRoy Parker. His father, Max Parker, had a small farm in Circleville, Utah. It was used as a hideout for outlaws and one of those who made regular visits was Mike Cassidy, who had a big influence on Robert Parker and he eventually adopted the name Butch Cassidy.

Cassidy became a cowboy and helped drive cattle to Telluride, Colorado. He soon abandoned this job and on 24th June, 1889, Cassidy, Tom McCarty and Matt Warner, held up the San Miguel Valley Bank. Over the next few years Cassidy's gang robbed banks in Idaho.

The gang eventually escaped to the Robbers' Roost in Utah. Cassidy now formed a new gang that became known as the Wild Bunch. This include Harry Longbaugh (the Sundance Kid), Ben Kilpatrick, Harvey Logan, William Carver, George Curry, Elza Lay, Bob Meeks and Harvey Logan.

In 1900 Longbaugh met Butch Cassidy. He moved to the Robbers' Roost in Utah and joined what became known as the Wild Bunch. As well as Cassidy the gang included Ben Kilpatrick, Harvey Logan, William Carver, George Curry, Laura Bullion, Elza Lay and Bob Meeks.

The name Wild Bunch was misleading as Cassidy always tried to avoid his gang hurting people during robberies. His gang were also ordered to shoot at the horses, rather than the riders, when being pursued by posses. Cassidy always proudly boasted that he had never killed a man. The name actually came from the boisterous way they spent their money after a successful robbery.

On 2nd June, 1899, Cassidy, Curry, Logan and Lay took part in the highly successful Union Pacific train holdup at Wilcox, Wyoming. After stealing $30,000 the gang fled to New Mexico. On 29th August, 1900, Cassidy, with the Sundance Kid, Logan and two unidentified gang members, held up the Union Pacific train at Tipton, Wyoming. This was followed by a raid on the First National Bank of Winnemucca, Nevada (19th September, 1900) that netted $32,640. The following year the gang obtained $65,000 from the Great Northern train near Wagner, Montana.

George Curry was killed by Sheriff Jesse Tyler on 17th April, 1900. The following year William Carver and Ben Kilpatrick were ambushed by Sheriff Elijah Briant and his deputies at Sonora, Texas. Carver died from his wounds three hours later. Kilpatrick escaped but he was captured in St Louis with another gang member, Laura Bullion, on 8th November, 1901. Kilpatrick was found guilty of robbery and was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Another gang member, Harvey Logan was captured on 15th December, 1901.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid began to think that being an outlaw in America was becoming too dangerous and decided to start a new life in South America. On 29th February, 1902, the two men and Etta Place, left New York City aboard the freighter, Soldier Prince. When they arrived in Argentina they purchased land at Chubut Province.

After farming for nearly four years the men decided to return to crime and in March 1906 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid robbed a bank of $20,000 in San Luis Province. During the raid a banker was killed. Other raids followed at Bahia Blanca (Argentina), Eucalyptus (Bolivia) and Rio Gallegos (Argentina).

In 1909 the men were back in Bolivia. One account claims that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were killed in a shoot-out at San Vicente. However, the police were not able to positively identify the two dead men. According to another source the men were killed while trying to rob a bank in Mercedes, Uruguay in December, 1911.

Ben Kilpatrick, Henry Logan and Robert Parker (Butch Cassidy)

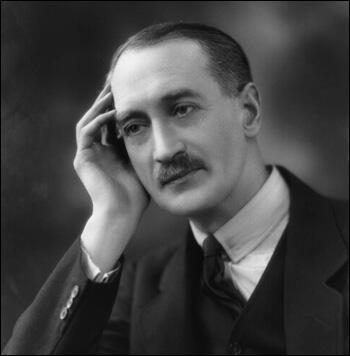

On this day in 1875 Christopher Thomson, the son of Major-General Christopher Thomson, was born in India on 13th April, 1875. After being educated at Cheltenham College and the Royal Military Academy, he joined the Royal Engineers in 1894.

Thomson served in Mauritius (1896-1899) and South Africa (1899-1902) during the Boer War, where he won two medals and was mentioned in dispatches.

After returning from South Africa he taught at the Engineering School at Chatham and the Staff College, Camberley. In 1911 Thomson went to the War Office where he served under Sir Henry Wilson, director of military operations. The following year he became military attaché with the Serbian Army where he remained throughout the Turkish and Bulgarian campaigns.

On the outbreak of the First World War he was sent to Belgium where he was liaison officer with the Belgian Army. In February 1915, Thomson became military attaché in Bucharest. After the German invasion of Rumania Thomson was sent to Palestine and took part in the advance on Jerusalem. He commanded a brigade at the capture of Jericho and was awarded the D.S.O. in 1918.

Promoted to the rank of brigadier-general, Thomson was a member of the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference and was highly critical of the Versailles Peace Treaty. In 1919 Thomson resigned from the army to stand as the Labour Party candidate at Bristol. He was unsuccessful and he was also defeated at the 1922 General Election. He also lost at St. Albans in 1923.

After the war Thomson published two important books on European politics, Old Europe's Suicide (1919) and Victors and Vanquished (1924). When Ramsay MacDonald formed the first Labour government in 1924, he raised Thomson to the peerage and appointed him as secretary of state for air. Thomson was largely responsible for the government's decision to start a programme of airship building that included R.100 and R101.

After the fall of MacDonald's government, Thomson became one of the leaders of the Labour Party in the House of Lords. He served as chairman of the Aeronautical Society and the Air League. He also published his book Air Facts and Problems (1927).

Following the Labour victory at the 1929 General Election, Thomson was once again appointed as secretary of state for air. Christopher Thomson, Baron of Cardington, was killed when a passenger of the R.101 airship that crashed on 5th October 1930.

On this day in 1945 Archibald MacLeish makes a radio broadcast on the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. "It has pleased God in His infinite wisdom to take from us the immortal spirit of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 3rd president of the United States. The leader of his people in a great war, he lived to see the assurance of the victory but not to share it. He lived to see the first foundations of the free and peaceful world to which his life was dedicated, but not to enter on that world himself. His fellow countrymen will sorely miss his fortitude and faith and courage in the time to come. The peoples of the earth who love the ways of freedom and of hope will mourn for him. But though his voice is silent, his courage is not spent, his faith is not extinguished. The courage of great men outlives them to become the courage of their people and the peoples of the world. It lives beyond them and upholds their purposes and brings their hopes to pass."

On this day in 1945 Allied troops liberate Belsen and Buchenwald. Belsen (also known as Bergen-Belsen) was a concentration camp in north-west Germany. Josef Kramer of the Schutzstaffel (SS) was placed in charge and the camp was staffed by members of the SS Death's Head units. Built for 10,000 prisoners it contained 70,000 in 1945. As well as the one built at Belsen, concentration camps were also built at Dachau and Buchenwald (Germany), Mautausen (Austria), Theresienstadt (Czechoslovakia) and Auschwitz (Poland).

The Belsen camp was liberated on 15th April, 1945 by the British 11th Armoured Division. One of these soldiers, Peter Combs, later recalled: "The conditions in which these people live are appalling. One has to take a tour round and see their faces, their slow staggering gait and feeble movements. The state of their minds is plainly written on their faces, as starvation has reduced their bodies to skeletons. The fact is that all these were once clean-living and sane and certainly not the type to do harm to the Nazis. They are Jews and are dying now at the rate of three hundred a day. They must die and nothing can save them - their end is inescapable, they are far gone now to be brought back to life."

With the troops was the journalist, Richard Dimbleby: "In the shade of some trees lay a great collection of bodies. I walked about them trying to count, there were perhaps 150 of them flung down on each other, all naked, all so thin that their yellow skin glistened like stretched rubber on their bones. Some of the poor starved creatures whose bodies were there looked so utterly unreal and inhuman that I could have imagined that they had never lived at all. They were like polished skeletons, the skeletons that medical students like to play practical jokes with. At one end of the pile a cluster of men and women were gathered round a fire; they were using rags and old shoes taken from the bodies to keep it alight, and they were heating soup over it. And close by was the enclosure where 500 children between the ages of five and twelve had been kept. They were not so hungry as the rest, for the women had sacrificed themselves to keep them alive. Babies were born at Belsen, some of them shrunken, wizened little things that could not live, because their mothers could not feed them."

On this day in 1953 the CIA launches the mind-control program Project MKULTRA. In 1941 Donald Ewen Cameron began working for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). However, in 1943 he went to Canada and established the psychiatry department at Montreal's McGill University and director of the newly-created Allan Memorial Institute.

Cameron continued to work for the OSS and in November 1945, Allen Dulles sent him to Germany to examine Rudolf Hess in order to assess if he was fit to stand trial at Nuremberg. According to one source, Dulles had told Cameron, that he believed the Hess he was about to examine was not the real Hess and that he had already been executed on the orders of Winston Churchill. (Gordon Thomas, Journey into Madness, 1993, pages 167-68).

It has been argued that Cameron might have been sent to Nuremberg to help the British intelligence services with a problem concerning the real reasons why Rudolf Hess arrived in Scotland in May 1941. Cameron’s task was to remove Hess’s memory of past events. This is why in 1946 Hess was unable to recognize his former friends and colleagues such as Hermann Goering, Julius Streicher and Joachim von Ribbentrop. Cameron next job was to provide Hess with a new memory about events dating back to May 1941. That is why Hess was able to provide Major Douglas M. Kelley with a comprehensive account of his trip to Scotland.

After the war Cameron worked at the Albany State Medical School. Cameron developed the theory that mental patients could be cured by treatment that erased existing memories and by rebuilding the psyche completely. According to his research assistant, Dr. Peter Roper, "He (Cameron) had a technician called Leonard Rubenstein who modified cassettes so there was an endless tape, it could keep repeating itself for hours at a time. If Cameron could give a positive message, eventually a patient would respond to it." Cameron would play the tapes to his patients for up to 86 days, as they slipped in and out of insulin-induced comas.

In the late 1940s Cameron developed a new treatment for mental illness. The authors of Double Standards argue that his "major inspiration was the British psychiatrist William Sargent, whom Cameron considered to be the leading expert on Soviet brainwashing techniques. Cameron took this work and used it for what he called 'depatterning'. He believed that after inducing complete amnesia in a patient, he could then selectively recover their memory in such a way as to change their behaviour unrecognisably."

In 1953 Cameron developed what he called "psychic driving". Cameron developed the theory that mental patients could be cured by treatment that erased existing memories and by rebuilding the psyche completely. According to his research assistant, Dr. Peter Roper, "He (Cameron) had a technician called Leonard Rubenstein who modified cassettes so there was an endless tape, it could keep repeating itself for hours at a time. If Cameron could give a positive message, eventually a patient would respond to it." Cameron would play the tapes to his patients for up to 86 days, as they slipped in and out of insulin-induced comas.

Cameron discovered that "once a subject entered an amnesiac, somnambulistic state, they would become hypersensitive to suggestion". In other words they could be brainwashed. The CIA became aware of Cameron's research and in 1957 Cameron was recruited by Allen Dulles, Director of the CIA, to run Project MKULTRA. Documents released in 1977 show that MKULTRA was a "mind control" program. As it was illegal for the CIA to conduct operations on American soil, Cameron was forced to carry out his experiments at the Allan Memorial Institute in Canada. The CIA arranged funding via Cornell University in New York.

Cameron had to commute to Montreal every week to carry out his work. According to official documents, Cameron was paid $69,000 from 1957 to 1964 to carry out MKULTRA experiments at the Allan Memorial Institute. Documents released in 1977 revealed that thousands of unwitting subjects were tested on as part of the MKULTRA program.

Dr. Peter Roper later claimed that Cameron and his team had visits from senior military officers "who briefed us on brainwashing techniques". One newspaper journalist later claimed in The Sunday Times that "using techniques similar to those portrayed in the celebrated novel the Manchurian Candidate, it was believed that people could be brainwashed and reprogrammed to carry out specific acts."

On this day in 1956 Emil Nolde died. Emil Nolde was born as Emil Hansen, near the village of Nolde, Germany, on 7th August, 1867. His parents, devout Protestants, were peasants. "Of Danish-German lineage, he was part of an ethnic minority that opted for life in the German Reich even under foreign citizenship. He became a carver and draftsman and in 1892 began creating watercolours of mountain motifis in Switzerland."

In 1892 he became a drawing instructor at the Museum of Industrial and Applied Arts. His main objective was to become a full-time artist but it was not until 1905 that he had his first art exhibition. The following year he briefly joined with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel to form Die Brücke, the first group of German Expressionist painters. Kirchner and his friends were all in their early to mid-20s, determined, they said, "to wrest freedom for our actions and our lives from the older, comfortably established forces."

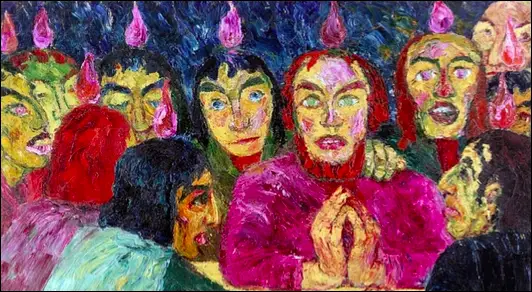

Nolde's held anti-Semitic views and this was expressed in the Pentecost (1909). However, the painting was rejected for an exhibition by the Berlin Secession, an artist group founded in 1898 in opposition to European salons and as a defender of traditional German culture. "Nolde was deeply attached to the work depicting the visitation of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus Christ’s apostles after their savior’s death and resurrection". After its rejection Nolde wrote a scathing letter to Berlin Secession president Max Liebermann. The letter was leaked to the press and Nolde never forgave Liebermann, a Jewish German, and accused him of subverting true German culture. "Throughout his life Nolde suffered from negative art-criticism and in this anti-Semitic conspiracy theory he found something it could be convincingly attributed to.”

An example of Nolde's expressionism can be seen in The Party (1911). "It is a gathering of cold-eyed strangers with yellow faces. Sex hums through the bright light but so does menace." Nolde's wife, Ada Vilstrup worked as a dancer. "Its louche characters and hubbub inspired vivid graphics, stage-lit in watercolour." Nolde was at the forefront of "a generation of German artists who eschewed saccharine Impressionism for a new, emotionally charged vocabulary. His debt to both his forebears and contemporaries is evident: the harrowing realism of Grünewald rubs shoulders with the heartfelt, early depictions of peasants by Nolde’s great hero Van Gogh; haunted, Ensor-like masks jostle with something like the gaiety of Toulouse-Lautrec."

The following year he painted The Candle Dancers (1912). According to Jonathan Jones: "It is the German answer to Matisse’s Dance. It is a lot more chaotic and frenzied, a confession of lust and intoxication. Two women wearing nothing but translucent skirts are throwing their limbs about wildly as they jump between lighted candles. Nolde juxtaposes their purple-pink flesh with a red and gold background like the fires of hell.... Yet this erotic reverie is fraught, uneasy. Nolde, who grew up in farm country and regularly returned there to paint, finds pre-first world war Berlin a corrupt, scary place."

Nolde held anti-Semite views and in a letter sent to a friend in 1911 drew a distinction between “Jews” and “Germans” and claimed that the leaders of the Berlin Secession art movement, such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Max Pechstein, were Jews. He added that “the art dealers are all Jews”, as were the “leading art critics” and that “the entire press was at their disposal”. He went on to make the allegation that the Secession movement was spreading like “dry rot” throughout the country.

Nolde became known for his harsh, almost grotesque depictions of biblical scenes. In 1921 Emil Nolde painted Paradise Lost. It was highly controversial but it had its supporters. Calvin Seerveld has argued: "The oil painting catches in vivid, sensuous colour the aftermath of the fall into sin by the disobedient action of Eve and Adam. The yellow, orange-haired Eve stares out at us unseeing, listless and disconsolate. Bearded Adam is grim, faced with the long haul of hard labour ahead of him on a cursed brown earth. The serpent curled around a tree, beady-eyed with fang hanging out, separates the disgruntled pair. A saber-toothed lion presses forward out of the background (left), while a couple of red flowers and trees (right) hint at the garden of Eden left behind. Nolde depicts the rough loneliness and tiresome petulence that are the wages of sin for us elemental, agitated humans, world with an end."

Jonathan Jones claims that Nolde's anti-Semitism can be seen in his paintings: "Looking at the alien, weirdly coloured faces that populate Nolde’s nightmare world, I start to see features that are troubling not aesthetically but historically. Does one of the men in his 1908 painting Market People have a hooked nose straight out of antisemitic caricature? And are the theatre-going couple in 1911’s In the Box being similarly reduced to antisemitic stereotypes? I wonder if I am overreacting, as the gallery labels appear blithely unaware. Then finally in front of Nolde’s 1921 triptych Martrydom there is no room for doubt. As Christ suffers on the cross, two monstrously caricatured Jewish witnesses gloat in the foreground. This is a modernist version of a very ancient hate."

Nolde was strongly opposed to the Russian Revolution and saw it as part of a Jewish conspiracy. In 1931 he wrote that “the whole Soviet system was of Jewish origin and served Jewish interests”, which were to use “the power of money” to gain “world domination”. He supported Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party and on 9th November, 1933, attended a dinner commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed coup in which Nazis attempted to seize power from the Bavarian government. “The Führer is great and noble in his aspirations and a genius man of action” Nolde wrote in a letter to a friend the following day. He also raised concerns that Hitler “is still being surrounded by a swarm of dark figures in an artificially created cultural fog.” The “dark figures” to which he referred were Jewish Germans who, the artist believed, sought to destroy what he considered “pure” German art through cultural diversity.

Barry Schwabsky has tried to explain Nolde's Anti-Semitism: "Nolde’s psychology will sound familiar to anyone who has ever spent much time around artists. There’s a certain significant minority among them whose arrogant certainty that they have never been properly recognized - and somehow no amount of recognition may ever be quite enough - tends to devolve into fantasies of persecution, the feeling that some cabal or mafia is arrayed against them. For Nolde, this was the Jews. In another time and place, this obsession might have remained a private affair, known only to a few intimates, but Nolde had the moral bad luck to be a contemporary of the Nazis, of whom he became an early and avid supporter."

Nolde was determined to enter Hitler’s good graces. A year after meeting him at the dinner party, he wrote an autobiography modeled on Hitler’s Mein Kampf entitled Jahre der Kämpfe (or Years of Struggle, using the plural of “Kampf”). In the book he advocated eugenics: “Some people, particularly the ones who are mixed, have the urgent wish that everything - humans, art, culture - could be integrated, in which case human society across the globe would consist of mutts, bastards and mulattos.”

Nolde welcomed the action that Hitler took against the Jews. He not only denounced his fellow artist Max Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan for how to remove Jews from German society. At the time several leading Nazis, including Joseph Goebbels and Albert Speer had paintings by Nolde on their walls. Goebbels, the head of the Culture Ministry, served as a honorary patron of an exhibition on Italian Futurism in Berlin in March, 1934. In a speech made in June 1934, Goebbels argued "We National Socialists are not un-modern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters."

Goebbels was in a minority and Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a senior figure in the Nazi Party, wrote a pamphlet entitled, The Struggle for Art: (1932) attacking the knd of modern art being produced by people like Nolde. "Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form... The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art."

Alois Schardt, a member of the Nazi Party and one of the directors at the Berlin National Art Gallery, was a defender of the work of Emile Node. He saw the Expressionist struggle as a spiritual renewal and as a return to the Germanic heritage. In his lecture, What is German Art? Schardt presented his theoretical justification for his position. He argued there was a direct link between the nonobjective ornamentation of the German bronze age and Expressionist painting. "The decline of German art began in 1431 when naturalism began to impringe on expressive art. Everything created after the first century in Germany was of only historical and documentary value and was essentially un-German."

Nolde did not paint in "the hyper-realistic style that Hitler preferred, favoring instead bold brushstrokes and electrifying colors to evoke visceral feelings of primal passion." Hitler hated Emil Nolde's work commenting: "Whatever he paints are nevertheless always piles of manure.” In the same year as he took power, the Führer repeatedly described Nolde as a “pig” and swore that he would not spend a penny of the new regime’s money on giving him commissions. Hitler also announced that gallery directors would be instructed not to buy any more of his works on pain of imprisonment.

When Hitler gained power he appointed Adolf Ziegler, a strong supporter of Schultze-Naumburg, as his artistic adviser. In November, 1933, Schardt was dismissed from office. In January 1934 Hitler had appointed Alfred Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Ziegler got support from Rosenberg in his disagreement with Goebbels. Rosenberg saw his mission to preserve the "folkish ideology in its purest form" and rejected Goebbels's belief that artists such as Heckel, Nolde and Barlach were representative of contemporary Germany's "indigenous Nordic" art.

Hitler was asked to intervene in the dispute. He made his position clear in a speech in September, 1934. Hitler argued that there were "two dangers" that National Socialism had to overcome. First, the iconoclastic "saboteurs of art," were threatening the development of art in Nazi Germany. "These charlatans are mistaken if they think that the creators of the new Reich are stupid enough or insecure enough to be confused, let alone intimidated, by their twaddle. They will see that the commissioning of what may be the greatest cultural and artistic projects of all time will pass them by as if they had never existed."

In 1936 Adolf Ziegler became President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of the Cultural Ministry under Joseph Goebbels. Ziegler made all artists join the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. In this way it became possible to prevent artists who were opposed to the policies of the Nazi government from working. For example, Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. However, he was eventually sacked as professor at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. Dix's dismissal letter said that his work "threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves."

In June 1936, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Horrible examples of art Bolshevism have been brought to my attention... I want to arrange an exhibit in Berlin of art from the period of degeneracy. So that people can see and learn to recognize it." By the end of the month he had obtained Hitler's permission to requisition "German degenerate art since 1910" from public collections for the show. Goebbels actually liked modern art and was a collector of the work of Emil Nolde. As Richard J. Evans has pointed out: "Its political opportunism was cynical even by Goebbels's standards. He knew that Hitler's hatred of artistic modernism was unquestionable, and so he decided to gain favour by pandering to it, even though he did not share it himself."

On 27th November, 1936, Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works."

Ziegler and his entourage toured German galleries and museums and picked out works to be taken to the new exhibition, some museum directors were furious, refused to co-operate, and pleaded with Hitler to obtain compensation if the the confiscated works were sold abroad. Such resistance was not tolerated and some of them lost their jobs. Over a 100 works were seized from the Munich collections, and comparable numbers from museums elsewhere.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition organized by Adolf Ziegler and the Nazi Party in Munich took place between 19th July to 30th November 1937. The exhibition presented 650 works of art, confiscated from German museums. This included 27 of Nolde’s paintings, watercolors, and etchings. The day before the exhibition started, Hitler delivered a speech declaring "merciless war" on cultural disintegration. Degenerate art was defined as works that "insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill". Whereas these artists are "men who are nearer to animals than to humans, children who, if they lived so, would virtually have to be regarded as curses of God."

Ziegler made a speech at the opening of the exhibition. "Our patience with all those who have not been able to fall in line with National Socialist reconstructions during the last four years is at an end. The German people will judge them. We are not scared. The people trust, as in all things, the judgment of one man, our Führer. He knows which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character... What you are seeing here are the crippled products of madness, impertinence, and lack of talent... I would need several freight trains clear our galleries of this rubbish... This will happen soon."

The exhibition included paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 artists. This included work by Kathe Kollwitz, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Paul Klee, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Beckmann, Christian Rohlfs, Oskar Kokoschka, Lyonel Feininger, Ernst Barlach, Otto Müller, Karl Hofer, Max Pechstein, Lovis Corinth, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Willi Baumeister, Kurt Schwitters, Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky.

The exhibition cleverly manipulated visitors to loathe and ridicule the art on show. As Nausikaä El-Mecky has pointed out: "The shock-value was enhanced by only allowing over-18s into the exhibition. The lines for the Degenerate Art Exhibition went around the block. Inside, many pictures had been taken out of their frames, and were attached to walls that were emblazoned with outraged slogans. Rather than whispering respectfully, people pointed and snickered. The paintings and sculptures had lost their status as artworks, and were now reduced to dangerous and outrageous rubbish."

Visitors found that the works of art were "deliberately badly displayed, hung at odd angles, poorly lit, and jammed up together on the walls, higgledy-piggledy". They carried titles such as Farmers Seen by Jews, Insult to German Womanhood, and Mockery of God. "They were intended to express a congruity between the art produced by mental asylum inmates... and the distorted perspectives adopted by the Cubists and their ilk, a point made explicit in much of the propaganda surrounding the assault on degenerate art as the product of degenerate human beings."

The objective was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them". The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish. Jonathan Petropoulos, the author of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (2014) has pointed out that works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist... The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous." (34) One of the visitors commented: "The artists ought to be tied up next to their pictures, so that every German can spit in their faces - but not only the artists, also the museum directors who, at a time of mass unemployment, poured vast sums into the ever-open jaws of the perpetrators of these atrocities."

The exhibition drew 2,009,899 visitors. After the exhibition closed, the work was confiscated. Among those who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Otto Dix (260), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all.

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) began on the 10th November, 1938. Jewish homes, hospitals and schools were ransacked as attackers demolished buildings with sledgehammers and an estimated 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. On 21st November, it was announced in Berlin by the Nazi authorities that 3,767 Jewish retail businesses in the city had either been transferred to "Aryan" control or closed down. Further restrictions on Jews were announced that day. To enforce the rule that Jewish doctors could not treat non-Jews, each Jewish doctor had henceforth to display a blue nameplate with a yellow star - the Star of David - with the sign: "Authorised to give medical treatment only to Jews." German bookmakers were also forbidden to accept bets from Jews.

Emil Nolde reacted to these crimes in a letter to a friend where he commented that he could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich giving his support to Jewish persecution, explaining that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”.

The Nazi government insisted that Nolde, despite his party membership, was not allowed to paint. Despite a personal appeal to his friend, Baldur von Schirach, this order was not changed and his art was considered "as ugly and anti-German in spirit, imbued instead with the polluting aesthetics of Africa, Bolshevism, and Jewry." Nolde retreated to his home in Sebüll, a remote area in Frisia, the northwest region of Germany "considered by many Germans to be the cradle of the nation’s language and culture. There, Nolde began crafting an image as a persecuted artist that he promoted to the Allies and his fellow Germans after the war."

Ada Nolde wrote to a friend: "The most German, Germanic, most loyal artist is excluded. It is thanks for his struggle against foreigners and the Jews, thanks for his great love for Germany, despite the fact that it would have been so easy for him to move to the other camp due to the resignation of North Schleswig. But it is mainly thanks for the great art to which he dedicated his life. It is thanks for his membership of the party in which, despite many mistakes, he sees the solution to the people's problems."

Nolde attempted to persuade Hitler of his loyalty by changing the subject matter. Nolde had reacted to the attacks on his "biblical figure paintings by not painting religious subjects after 1934 - and therefore no Jews either." Instead he concentrated on painting subjects that he thought the Nazi government would find acceptable: "Motifs from the Nordic world of legends increasingly took their place: kings, warriors and long-bearded Vikings. He was particularly inspired by Snorri Sturluson's collection of Icelandic royal legends... the first reading of this book led to a series of works with Viking motifs."

On Hitler's death Nolde wrote: "He (Hitler) was my enemy. His cultural dilettantism brought my art and me much sorrow, persecution, and condemnation." (42) He now attempted to turn himself into the personification of the persecuted modern artist: "Cooperative art historians and politicians alike, needing to believe that there always was another Germany, a resistant and independent-minded Germany that, by whatever subterfuge, managed to quietly persist under the heel of Hitler’s regime... In order to forge a hero for themselves, they seized on the story of the painter condemned as degenerate and forbidden to paint.... Since Nolde neither painted overtly Nazi subjects nor changed his style to suit the Führer’s taste, that’s easier to do by way of texts than artworks."

Emil Nolde died on 13th April, 1956. The Nolde Foundation Seebüll established by Ada and Emil in 1946, played an important role in the construction of the public Nolde image. Art critics continued to protect Nolde's reputation and "It was a farce that most Germans were happy to entertain". In 2013, historian Manfred Reuther published his official biography Emil Nolde. Mein Leben (Emil Nolde. My Life), the 456-page book omitted any mention of Nolde’s admiration for Adolf Hitler and condensed his life during the Second World War to roughly five pages.

Bernhard Fulda, the author of Press and Politics in the Weimar Republic (2009), carried out research into Emil Nolde at the Nolde Foundation. He was granted unrestricted access to archives containing more than 25,000 documents at the Nolde Foundation in Seebuell, near the Danish border, where the artist lived. This included a large number of anti-Semitic letters written by Nolde. Fulda's book, Emil Nolde: The Artist During the Third Reich, was published in May, 2019.

In September, 2019, Fulda and his wife, Aya Soika (an art curator) arranged an exhibition of Nolde's work in Berlin. According to the Times of Israel, "The exhibition includes documents from throughout Nolde's career, including anti-Semitic letters from the artist dating back to before World War I. It explores his conviction that he was a misunderstood artistic genius and his claim that he was boycotted by a supposedly Jewish-dominated art scene."

Fulda and Soika also wrote the catalogue for the exhibition. The art critics who wrote the reviews relied heavily on their account of Nolde. Up until this time Angela Merkel was a great fan of his work. But after this bad publicity she removed Nolde's Breakers, a striking 1936 seascape, from a prominent place on her office wall. The painting was completely non-political but Merkel thought she could no longer be seen as liking his work.

On this day in 1962 Culbert Olson died. Culbert Olson was born in Filmore, Utah on 7th November, 1876. His mother was involved in the campaign for women's suffrage and eventually became the first female elected official in Utah. He was brought up in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon) but rejected religion at an early age.

At the age of fourteen Olson left school and found work as a telegraph operator. In 1890 Olson enrolled in the Brigham Young University at Provo, Utah. After graduating he found work as a journalist for the Daily Ogden Standard.

Olson took a keen interest in politics and in 1896 campaigned for William Jennings Bryan. He later moved to Washington as a newspaper correspondent.

Olson studied law at George Washington University and the University of Michigan and was admitted to the Utah Bar in 1901. Olson became a lawyer in Salt Lake City. A member of the Democratic Party, Olson was elected to the state legislature of Utah in 1916. Over the next four years he advocated an end to child labour, progressive taxation, old age pensions, government control of public utilities and legislation to protect the rights of trade unionists.

In 1920 Olson moved to Los Angeles. In his law practice he gained a reputation for investigating business fraud. In the 1924 presidential election he campaigned for Robert La Follette and the Progressive Party and later for the novelist, Upton Sinclair, when he tried to become Governor of California.

A strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, in 1934 Olson became state chairman of the Democratic Party. In November 1938 Olson was elected as Governor of California, the first Democrat to hold this office for forty-four years.

One of the first acts was to pardon Tom Mooney, a trade union leader who had been convicted of a bombing which occurred in San Francisco in 1916. Although strong evidence existed that the District Attorney of the time, Charles Fickert, had framed Mooney, the Republican governors during this period, William Stephens (1917-1923), Friend Richardson (1923-1927), Clement Young (1927-1931), James Rolph (1931-1934) and Frank Merriam (1934-39) refused to order his release. In October 1939, Olson pardoned Warren Billings, a friend of Mooney's who had also been imprisoned for the bombing.

As governor Olson tried to introduce an advanced New Deal in California. In Olson's words that would provide "economic security from the cradle to the grave, under a government that recognizes the right to an education, to employment on a basis of just reward, and to retirement at old age in comfort and decency, as inalienable as the right to life itself."

Olson was defeated in his campaign to be re-elected in 1942. Olson, an atheist, told a friend that he lost "because of the active hostility of a certain privately owned power corporation and the Roman Catholic Church in California."

In 1957 Culbert Olson became president of the United Secularists of America and held the post until his death in Los Angeles on 13th April, 1962.