Cowboys

The term cowboy was first used in Texas in the 1860s to describe the work of men controlling cattle on horseback. After the American Civil War there was a great demand for meat in the northern and eastern parts of the United States. It is estimated that at this time there were over 6 million Longhorns in Texas.

The task of the cowboy was to take part in cattle drives where cattle were driven from Texas to the railroad cowtowns of Abilene, Dodge City, Wichita and Newton. The cattle business eventually spread to Kansas, Wyoming, Montana, New Mexico, Colorado and Arizona.

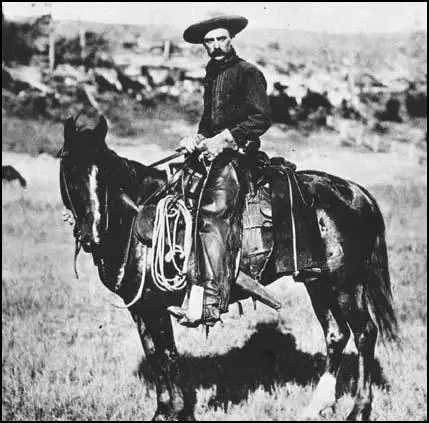

As well as driving cattle to the cowtowns the cowboys were responsible for branding them with the owners's identifying mark on the hides of the animal. The cowboy wore chaps over his levis to protect his legs from the bush. He carried a lariat which he used to catch and secure the cattle. The rope would then be wrapped round the horn on his saddle.

It has been claimed by one historian that around a quarter of the 35,000 cowboys in the American West were black. This included Nat Love who published his autobiography The Life and Adventures of Nat Love in 1907.

Famous cowboys included Billy the Kid, Perry Owens, Butch Cassidy, Sundance Kid, Ben Kilpatrick, Clay Allison, Dick Brewer, Bill Longley, Jeff Milton, George Scarborough, Jack Omohundro, William Carver and John Wesley Hardin. Cowboys were paid about ten dollars a week. After a long cattle drive they would often spend the money on drink, prostitutes and gambling in the railroad cowtowns.

Primary Sources

(1) D. W. Wilder, Annals of Kansas (1882)

The typical cowboy wears a white hat, with a gilt cord and tassel, high-top boots, leather pants, a woolen shirt, a coat, and no vest. On his heels he wears a pair of jingling Mexican spurs, as large around as a teacup. When he feels well (and he always does when full of what he calls "Kansas sheep-dip"), the average cowboy is a bad man to handle. Armed to the teeth, well mounted, and full of their favorite beverage, the cowboys will dash through the principal streets of a town, yelling like Comanches. This they call "cleaning out a town."

(2) Theodore Roosevelt, Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (1888)

The cowboys, who have supplanted these old hunters and trappers as the typical men of the plains, themselves lead lives that are almost as full of hardship and adventure. The unbearable cold of winter sometimes makes the small outlying camps fairly uninhabitable if fuel runs short; and if the line riders are caught in a blizzard while making their way to the home ranch, they are lucky if they get off with nothing worse than frozen feet and faces.

They are, in the main, hard-working, faithful fellows, but of course are frequently obliged to get into scrapes through no fault of their own. Once, while out on a wagon trip, I got caught while camped by a spring on the prairie, through my horses all straying. A few miles off was the camp of two cowboys, who were riding the line for a great Southern cow-outfit. I did not even know their names, but happening to pass by them I told of my loss, and the day after they turned up with the missing horses, which they had been hunting for twenty-four hours. All I could do in return was to give them some reading matter;something for which the men in these lonely camps are always grateful. Afterwards I spent a day or two with my new friends, and we became quite intimate. They were Texans. Both were quiet, clean-cut, pleasant-spoken young fellows, who did not even swear, except under great provocation and there can be no greater provocation than is given by a "mean" horse or a refractory steer. Yet, to my surprise, I found that they were, in a certain sense, fugitives from justice. They were complaining of the extreme severity of the winter weather, and mentioned their longing to go back to the South. The reason they could not was that the summer before they had taken part in a small civil war in one of the wilder counties of New Mexico. It had originated in a quarrel between two great ranches over their respective water rights and range rights, a quarrel of a kind rife among pastoral peoples since the days when the herdsmen of Lot and Abraham strove together for the grazing lands round the mouth of the Jordan. There were collisions between bands of armed cowboys, the cattle were harried from the springs, outlying camps were burned down, and the sons of the rival owners fought each other to the death with bowie-knife and revolver when they met at the drinking-booths of the squalid towns. Soon the smoldering jealousy which is ever existent between-the Americans and Mexicans of the frontier was aroused, and when the original cause of quarrel was adjusted, a fierce race struggle took its place. It was soon quelled by the arrival of a strong sheriff's posse and the threat of interference by the regular troops, but not until after a couple of affrays, each attended with bloodshed. In one of these the American cowboys of a certain range, after a brisk fight, drove out the Mexican vaqveros from among them. In the other, to avenge the murder of one of their number, the cowboys gathered from the country round about and fairly stormed the "Greaser" (that is, Mexican) village where the murder had been committed, killing four of the inhabitants. My two friends had borne a part in this last affair. They were careful to give a rather cloudy account of the details, but I gathered that one of them was "wanted" as a participant, and the other as a witness.

(3) Kansas State Record (5th August, 1871)

Before dark you will have an opportunity to notice that Abilene is divided by the railroad into two sections, very different in appearance. The north side is literary, religious and commercial, and possesses... Wilson's Chronicle, the churches, the banks, and several large stores of various description; the south side of the road is the Abilene of "story and song," and possesses the large hotels, the saloons, and the places where the "dealers in card board, bone and ivory" most do congregate. When you are on the north side of the track you are in Kansas, and hear sober and profitable conversation on the subject of the weather, the price of land and the crops; when you cross to the south side you are in Texas, and talk about cattle, varied by occasional remarks on "beeves" and "stock." Nine out of ten men you meet are directly or indirectly interested in the cattle trade; five at least out of every ten, are Texans. As at Newton, Texas names are prominent on the fronts of saloons and other "business houses," mingled with sign board allusions to the cattle business. A clothing dealer implores you to buy your "outfit" at the sign of the "Long Horns"; the leading gambling house is of course the "Alamo," and "Lone Stars" shine in every direction.

At night everything is "full up." The "Alamo" especially being a center of attraction. Here, in a well lighted room opening on the street, the "boys" gather in crowds round the tables, to play or to watch others; a bartender, with a countenance like a youthful divinity student, fabricates wonderful drinks, while the music of a piano and a violin from a raised recess, enlivens the scene, and "soothes the savage breasts" of those who retire torn and lacerated from an unfortunate combat with the "tiger." The games most affected are faro and monte, the latter being greatly patronized by the Mexicans of Abilene, who sit with perfectly unmoved countenances and play for hours at a stretch, for your Mexican loses with entire indifference two things somewhat valued by other men, viz: his money and his life.

It may be inferred from the foregoing that the Texan cattle driver is some what prone to "run free" as far as morals are concerned, but on the contrary, vice in one of its forms, is sternly driven forth from the city limits for the space of at least a quarter of a mile, where its 'local habitation" is courteously and modestly, but rather indefinitely designated as the "Beer Garden." Here all that class of females who "went through" the Prodigal Son, and eventually drove that young gentleman into the hog business, are compelled to reside. In the amusements we have referred to does the "jolly drover" while the night away in Abilene.

Day in Abilene is very different. The town seems quite deserted, the "herders" go out to their herd or disappear in some direction, and thus the town relapses into the ordinary appearance of towns in general. It is during the day, that, seated on the piazzas of the hotels, may be seen a class of men peculiar to Texas and possessing many marked traits of character. We allude to the stock raisers and owners, who count their acres by thousands and their cattle by tens of thousands.

(4) The Pueblo Chieftain (June, 1878)

The cowboy is apt to spend his money liberally when he gets paid off after his long drive from Texas, and the pimps, gamblers and prostitutes who spend the winter in Kansas City and other large towns, generally manage to get to the point where the boys are paid off so as to give them a good chance to invest their money in fun.

The people who own Dodge City and live there do not look with favor on the advent of these classes, and only tolerate them because they cannot well help themselves. They follow the annual cattle drive like vultures follow an army, and disappear at the end of the cattle driving and shipping season. It is this feature of the business that makes people averse to the Texas cattle business coming to their towns, and Dodge has already a strong element opposed to cattle coming there to be shipped.

(5) James Brisbin, The Beef Bonanza (1885)

If $250,000 were invested in ten ranches and ranges, placing 2,000 head on each range, by selling the beeves as fast as they mature, and all the cows as soon as they were too old to breed well, and investing the receipts in young cattle, at the end of five years there would be at least 45,000 head on the ten ranges, worth at least $18.00 per head, or $810,000. Assuming the capital was borrowed at 10 per cent interest, in five years the interest would amount to $125,000, which must be deducted; $250,000 principal, and interest for five years, compounded at 25 per cent per annum, would only be $762,938, or less than the value of the cattle exclusive of the ranches and fixtures. I have often thought if some enterprising persons would form a joint-stock company for the purpose of breeding, buying, and selling horses, cattle, and sheep, it would prove enormously profitable. I have no doubt but a company properly managed would declare an annual dividend of at least 25 per cent. Such a company organized with a president, secretary, treasurer, and board of directors, and conducted on strictly business principles, would realize a far larger profit on the money invested than if put into mining, lumber iron, manufacturing, or land companies. Nothing, I believe, would beat associated capital in the cattle trade, unless it would be banking and stock-raising would probably fully compete with even banking as a means of profit on capital invested in large sums.

Such a company should buy Texas cattle, locate them on ranges, placing 5,000 head on each ranch, then breed them up for the market, increasing quantity and quality as fast as possible, selling all beeves whenever mature, and cows as fast as they become too old to breed from or were not suitable for breeding purposes. As fast as beeves and cows were sold the first three years, the money realized should be used, or at least a good part of it, to fill up the herds with good young stock.

The ranches and ranges should be located with a view of ultimately buying the land or securing control of it for a long term of years. The company should operate and secure, to as great an extent as possible, the monopoly of government contracts and furnishing the Eastern markets with beef. It should aim to grow to be a controlling power in all that affected beef, and eventually it should not only pack beef and pork but tan hides and manufacture wool into cloth. It is not generally known that one-third of all the woolens used in the United States is sold west of the Mississippi River; but such is the fact, and the principal cause of this great consumption is because the climate of Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, Montana, and indeed all the plains and Rocky Mountain country is so cool that woolens are worn nearly the year round. The climate is admirably adapted for it, and there is no reason in the world why the largest pork and beef packeries, as well as tanneries, should not be established in the West. The beef business cannot be overdone. The census of the United States will probably show a population in 1880 of not less than 47,000,000 of people, and the cattle-raising does not keep pace with the rapid increase of population. In the Eastern and Middle states for the last ten years there has been a rapid decrease of cattle, and in a few years the West will be called on to supply almost the whole Eastern demand.

Land worth over $10.00 per acre is too valuable to be devoted to stock-raising, and farmers can do better in cereals. It is for this reason our Eastern farmers are giving up the cattle-breeding and devoting their lands to raising corn, wheat, rye, oats, and vegetables. They cannot compete with plains beef, for while their grazing lands cost them $50.00, $75.00, and $100.00 per acre, and hay has to be cut for winter feeding, the grazing lands in the West have no market value, and the cattle run at large all winter - the natural grasses curing on the ground and keeping the stock fat even in January, February, and March. Much of Montana, Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, and nearly all of Wyoming can never become an agricultural country, and the government will soon be called upon to put the grazing lands into market, so that our stock raisers may establish permanent ranches and buy their cattle ranges. It will very soon be cheaper to fence than to herd stock. The time, I believe, is not far distant when the West will supply the people of the East with beef for their tables; wool for their clothing; horses for their carriages, busses, and street railways; and gold and silver for their purses.

(6) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

About the last of February we got all our cattle branded and started for Abilene, Kansas, about the 1st of March. Jim Clements and I were to take these 1,200 head of cattle up to Abilene and Manning; Gip and Joe Clements were to follow with a herd belonging to Doc Bumett. Jim and I were getting $150 per month.

Nothing of importance happened until we got to Williamson County, where all the hands caught the measles except Jim and myself. We camped about two miles south of Corn Hill and there we rested up and recruited. I spent the time doctoring my sick companions, cooking, and branding cattle.

After several weeks of travel we crossed Red River at a point called Red River Station, or Bluff, north of Montague County. We were now in the Indian country and two white men had been killed by Indians about two weeks before we arrived at the town. Of course, all the talk was Indians and everybody dreaded them. We were now on what is called the Chisum Trail and game of all kinds abounded: buffalo, antelope, and other wild animals too numerous to mention. There were a great many cattle driven that year from Texas. The day we crossed Red River about fifteen herds had crossed, and of course we intended to keep close together going through the Nation for our mutual protection. The trail was thus one line of cattle and you were never out of sight of a herd. I was just about as much afraid of an Indian as I was of a coon. In fact, I was anxious to meet some on the warpath.

(7) Theodore Roosevelt, Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (1888)

During the winter-time there is ordinarily but little work done among the cattle. There is some line riding, and a continual lookout is kept for the very weak animals;usually cows and calves, who have to be driven in, fed, and housed; but most of the stock are left to shift for themselves, undisturbed. Almost every stock-growers' association forbids branding any calves before the spring round-up. If great bands of cattle wander off the range, parties may be fitted out to go after them and bring them back; but this is only done when absolutely necessary, as when the drift of the cattle has been towards an Indian reservation or a settled granger country, for the weather is very severe, and the horses are so poor that their food must be carried along.

The bulk of the work is done during the summer, including the late spring and early fall, and consists mainly in a succession of round-ups, beginning, with us, in May and ending towards the last of October.

But a good deal may be done in the intervals by riding over one's range. Frequently, too, herding will be practised on a large scale.

Still more important is the "trail" work; cattle, while driven from one range to another, or to a shipping point for beef, being said to be "on the trail." For years, the over-supply from the vast breeding ranches to the south, especially in Texas, has been driven northward in large herds, either to the shipping towns along the great railroads, or else to the fattening ranges of the North-west; it having been found, so far, that while the calf crop is larger in the South, beeves become much heavier in the North. Such cattle, for the most part, went along tolerably well-marked routes or trails, which became for the time being of great importance, flourishing &emdash;and extremely lawless &emdash;towns growing up along them; but with the growth of the railroad system, and above all with the filling up of the northern ranges, these trails have steadily become of less and less consequence, though many herds still travel them on their way to the already crowded ranges of western Dakota and Montana, or to the Canadian regions beyond. The trail work is something by itself. The herds may be on the trail several months, averaging fifteen miles or less a day. The cowboys accompanying each have to undergo much hard toil, of a peculiarly same and wearisome kind, on account of the extreme slowness with which everything must be done, as trail cattle should never be hurried. The foreman of a trail outfit must be not only a veteran cowhand, but also a miracle of patience and resolution.

(8) Hamlin Garland, Trailing the Cowboy (1906)

The cowboy may respect churches but because of his mode of life, he seldom becomes "mashed" on them. He is just as apt to swear as any other man. He carries no gun, and never seeks a quarrel. He is a good rider, and long experience has made him acquainted with all the wonderful evolutions and ramifications of a bucking bronco. He can throw a lasso with unerring aim, is in the saddle twelve hours a day and as much of a gentleman as any other man, considering the lack of opportunity to acquire what the world calls "polish" - and no more so. He is neither saint nor sinner; a jovial, lighthearted, hardworking young fellow, who minds his own business, but who will not be imposed upon.

As you mingle with these cowboys, you find in them a strange mixture of good nature and recklessness. You are as safe with them on the plains as with any class of men, so long as you do not impose upon them. They will even deny themselves for your comfort, and imperil their lives for your safety. But impose upon them, or arouse their ire, and your life is of no more value in their esteem than that of a coyote.

Morally, as a class, they are toulmouthed, blasphemous, drunken, lecherous, utterly corrupt. Usually harmless on the plains when sober, they are dreaded in towns, for then liquor has the ascendency over them. They are also as improvident as the veriest "Jack" of the sea...

They never own any interest in the stock they tend. This dark picture of the cowboys ought to be lightened by the statement that there is occasionally a white sheep among the black. True and devoted Christians are found in such company - men who will kneel down regularly and offer their prayers in the midst of their bawdy and cursing associates. They are like Lot in Sodom.

(9) Nat Love, The Life and Adventures of Nat Love (1907)

It was a bright, clear rail day, October 4, 1876, that quite a large number of us boys started out over the range hunting strays which had been lost for some time. We had scattered over the range and I was riding along alone when all at once I heard the well known Indian war whoop and noticed not far away a large party of Indians making straight for me. They were all well mounted and they were in full war paint, which showed me that they were on the war path, and as I was alone and had no wish to be scalped by them I decided to run for it. So I headed for Yellow Horse Canyon and gave my horse the rein, but as I had considerable objection to being chased by a lot of painted savages without some remonstrance, I turned in my saddle every once in a while and gave them a shot by way of greeting, and I had the satisfaction of seeing a painted brave tumble from his horse and go rolling in the dust every time my rifle spoke, and the Indians were by no means idle all this time, as their bullets were singing around me rather lively, one of them passing through my thigh, but it did not amount to much. Reaching Yellow Horse Canyon, I had about decided to stop and make a stand when one of their bullets caught me in the leg, passing clear through it and then through my horse, killing him. Quickly falling behind him I used his dead body for a breast work and stood the Indians off for a long time, as my aim was so deadly and they had lost so many that they were careful to keep out of range. But finally my ammunition gave out, and the Indians were quick to find this out, and they at once closed in on me, but I was by no means subdued, wounded as I was and almost out of my head, and I fought with my empty gun until finally overpowered. When I came to my senses I was in the Indians' camp.

My wounds had been dressed with some kind of herbs, the wound in my breast just over the heart was covered thickly with herbs and bound up. My nose had been nearly cut off, also one of my fingers had been nearly cut off. These wounds I received when I was fighting my captors with my empty gun. What caused them to spare my life I cannot tell, but it was I think partly because I had proved myself a brave man, and all savages admire a brave man and when they captured a man whose fighting powers were out of the ordinary they generally kept him if possible as he was needed in the tribe.

Then again Yellow Dog's tribe was composed largely of half breeds, and there was a large percentage of colored blood in the tribe, and as I was a colored man they wanted to keep me, as they thought I was too good a man to die. Be that as it may, they dressed my wounds and gave me plenty to eat, but the only grub they had was buffalo meat which they cooked over a fire of buffalo chips, but of this I had all I wanted to eat. For the first two days after my capture they kept me tied hand and foot. At the end of that time they untied my feet, but kept my hands tied for a couple of days longer, when I was given my freedom, but was always closely watched by members of the tribe. Three days after my capture my ears were pierced and I was adopted into the tribe. The operation of piercing my ears was quite painful, in the method used, as they had a small bone secured from a deer's leg, a small thin bone, rounded at the end and as sharp as a needle. This they used to make the holes, then strings made from the tendons of a deer were inserted in place of thread, of which the Indians had none. Then horn ear rings were placed in my ears and the same kind of salve made from herbs which they placed on my wounds was placed on my ears and they soon healed.