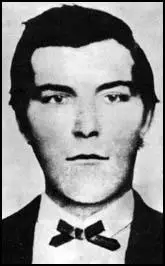

John Wesley Hardin

John Wesley Hardin was born in Bonham, Fannin County, Texas, on 26th May, 1853. He was the son of James Hardin, a Methodist preacher, and was named after John Wesley, the founder of Methodism.

Hardin was only 12 years old when members of the Confederate Army returned home after the American Civil War. The war had a powerful impact on Hardin and he developed a strong hatred of the freed slaves and killed his first black man when he was 15 years old. Hardin fled from home after the killing. As he was later to explain: "To be tried at that time for the killing of a Negro meant certain death at the hands of a court backed by Northern bayonets... thus, unwillingly, I became a fugitive not from justice, be it known, but from the injustice and misrule of the people who had subjugated the South."

In the next few weeks Hardin was to kill three more men. These were soldiers who had attempted to take him into custody. Hardin moved to Navarro County where he became a school teacher. This was followed by work as a cowboy. He then tried to make a living out of poker but this resulted in him killing Jim Bradley in a gambling row.

Hardin's next killing took place in Kosse, Texas when a man tried to rob him. As he pointed out later: "I told him that I only had about $50 or $60 in my pocket but if he would go with me to the stable I would give him more, as I had the money in my saddle pocket ... He said, "Give me what you have first." I told him all right, and in so doing, dropped some of it on the floor. He stooped down to pick it up and as he was straightening up I pulled my pistol and fired. The ball struck him between the eyes and he fell over, a dead robber."

In 1871 he was involved in taking cattle to Abilene where he met Wild Bill Hickok. Hardin later claimed he "killed five men on the journey and three more at his destination". After killing four black men he was arrested by the sheriff of Cherokee County. He escaped from jail in October 1872, and was soon back in trouble with the law. This included the killing of Charles Webb, deputy sheriff of Brown County, on 26th May, 1874.

Hardin fled to Florida and over the next few months killed six more men. With a $4,000 price on his head Hardin was pursued by several bounty hunters. Eventually he was captured by Captain John Armstrong and a party of Texas Rangers at Pensacola on 23rd July, 1877. The following year he was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He was taken to Huntsville in Texas and he spent his time studying law, theology and mathematics. Hardin regained his religious faith and became superintendent of the Sunday School in prison.

In 1894 Hardin was released from prison. He joined his children in Gonzales County (his wife Jane had died on 6th November, 1892) before moving to Karnes County, where he married Callie Lewis on 8th January, 1895. The marriage was not a success and Hardin moved to El Paso where he worked as a lawyer. Hardin also began writing his autobiography.

Hardin got in trouble in 1895 when he started claiming that he paid Jeff Milton and George Scarborough to kill Martin McRose. Milton and Scarborough were arrested but Hardin later withdrew his comments and the men were released.

His next dispute concerned John Selman. He began saying unpleasant things about Selman's son after he arrested Hardin's girlfriend for vagrancy. On 19th August, 1895, Selman shot John Wesley Hardin in the back of the head while he was standing at the Acme Saloon Bar.

The El Paso police found Hardin's unfinished autobiography in the house he rented in the town. This was handed over to his children and the book, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself was published in 1896.

Primary Sources

(1) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

The principles of the Southern cause loomed up in my mind ever bigger, brighter, and stronger as the months and years rolled on. I had seen Abraham Lincoln burned and shot to pieces in effigy so often that I looked upon him as a very demon incarnate, who was waging a relentless and cruel war on the South to rob her of her most sacred rights. So you can see that the justice of the Southern cause was taught to me in my youth, and if I never relinquished these teachings in after years, surely I was but true to my early training. The way you bend a twig, that is the way it will grow, is an old saying, and a true one. So I grew up a rebel.

(2) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

I stopped in the road and he came at me with his big stick. He struck me, and as he did it I pulled out a Colt's .44 six-shooter and told him to get back. By this time he had my horse by the bridle, but I shot him loose. He kept coming back, and every time he would start I would shoot again and again until I shot him down. I went to Uncle Clabe Houlshousen and brought him and another man back to where Mage was lying. Mage still showed fight and called me a liar. If it had not been for my uncle, I would have shot him again. Uncle Houlshousen gave me a $20 gold piece and told me to go home and tell father all about the big fight; that Mage was bound to die, and for me to look out for the Yankee soldiers who were all over the country at that time. Texas like other states, was then overrun with carpetbaggers and bureau agents who had the United States Army to back them up in their meanness. Mage shortly died in November, 1868. This was the first man I ever killed, and it nearly distracted my father and mother when I told them. All the courts were then conducted by bureau agents and renegades, who were the inveterate enemies of the South and administered a code of justice to suit every case that came before them and which invariably ended in gross injustice to Southern people, especially to those who still openly held on to the principles of the South. To be tried at that time for the killing of a Negro meant certain death at the hands of a court, backed by Northern bayonets; hence my father told me to keep in hiding until that good time when the Yankee bayonet should cease to govern. Thus, unwillingly, I became a fugitive, not from justice be it known, but from the injustice and misrule of the people who had subjugated the South.

(3) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

Bradley saw me and tried to cut me off, getting in front of me with a pistol in one hand and a Bowie knife in the other. He commenced to fire on me, firing once, then snapping, and then firing again. By this time we were within five or six feet of each other, and I fired with a Remington .45 at his heart and right after that at his head. As he staggered and fell, he said, "O, Lordy, don't shoot me any more." I could not stop. I was shooting because I did not want to take chances on a reaction. The crowd ran, and I stood there and cursed them loud and long as cowardly devils who had urged a man to fight and when he did and fell, to desert him like cowards and traitors.

(4) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

I had not been there long before the boys took me to a Mexican camp where they were dealing monte. I soon learned the rudiments of the game and began to bet with the rest. Finally I turned a card down and tapped the game. My card came and I said, "Pay the queen." The dealer refused. I struck him over the head with my pistol as he was drawing a knife, shot another as he also was drawing a knife. Well, this broke up the monte game and the total casualties were a Mexican with his arm broken, another shot through the lungs, and another with a very sore head.

We all went back to camp and laughed about the matter, but the game broke up for good and the Mexican camp was abandoned. The best people of the vicinity said I did a good thing. This was in February, 1871.

(5) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

I have seen many fast towns, but I think Abilene beat them all. The town was filled with sporting men and women, gamblers, cowboys, desperadoes, and the like. It was well supplied with bar rooms, hotels, barber shops, and gambling houses, and everything was open.

I spent most of my time in Abilene in the saloons and gambling houses, playing poker, faro, and seven-up. One day I was rolling ten pins and my best horse was hitched outside in front of the saloon. I had two six-shooters on, and, of course, I knew the saloon people would raise a row if I did not pull them off. Several Texans were there rolling ten pins and drinking. I suppose we were pretty noisy. Wild Bill Hickok came in and said we were making too much noise and told me to pull off my pistols until I got ready to go out of town. I told him I was ready to go now, but did not propose to put up my pistols, go or no go. He went out and I followed him. I started up the street when someone behind me shouted out, "Set up. All down but nine."

Wild Bill whirled around and met me. He said, "What are you howling about, and what are you doing with those pistols on?"

I said, "I am just taking in the town."

He pulled his pistol and said, "Take those pistols off. I arrest you."

I said all right and pulled them out of the scabbard, but while he was reaching for them, I reversed them and whirled them over on him with the muzzles in his face, springing back at the same time. I told him to put his pistols up, which he did. I cursed him for a long-haired scoundrel that would shoot a boy with his back to him (as I had been told he intended to do me). He said, "Little Arkansas, you have been wrongly informed."

I shouted, "This is my fight and I'll kill the first man that fires a gun."

Bill said, "You are the gamest and quickest boy I ever saw. Let us compromise this matter and I will be your friend.

(6) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

The fellow told me he would kill me if I did not give him $100. I told him that I only had about $50 or $60 in my pocket but if he would go with me to the stable I would give him more, as I had the money in my saddle pocket ... He said, "Give me what you have first." I told him all right, and in so doing, dropped some of it on the floor. He stooped down to pick it up and as he was straightening up I pulled my pistol and fired. The ball struck him between the eyes and he fell over, a dead robber.

(7) John Wesley Hardin described how he killed Charles Webb in his autobiography, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

I turned and faced the man whom I had seen coming up the street. He had on two six-shooters and was about fifteen steps from me, advancing. He stopped when he got to within five steps of me... and scrutinized me closely, with his hands behind him. I asked him:

"Have you any papers for my arrest?"

He said: "I don't know you."

I said: "My name is John Wesley Hardin."

He said, "Now I know you, but have no papers for your arrest."

"Well," said I, "I have been informed that the Sheriff of Brown County has said that Sheriff Karnes of this County was no sheriff or he would not allow me to stay around Comanche with my murdering pals."

As I turned around to go in the door, I heard someone say, "Look out. Jack." It was Bud Dixon, and as I turned around I saw Charles Webb drawing his pistol. He was in the act of presenting it when I jumped to one side, drew my pistol and fired.

In the meantime Webb had fired, hitting me in the left side, cutting the length of it, inflicting an ugly and painful wound. My aim was good and a bullet hole in the left cheek did the work. He fell against the wall and as he fell he fired a second shot, which went into the air.

(8) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

The simple fact is that Charles Webb had really come over from his own county that day to kill me, thinking I was drinking and at a disadvantage. He wanted to kill me to keep his name, and he made his break on me like an assassin would. He fired his first shot at my vitals when I was unprepared, and who blames a man for shooting under such conditions? I was at a terrible disadvantage in my trial. I went before the court on a charge of murder without a witness. The cowardly mob had either killed them or run them out of the county. I went to trial in a town in which three years before my own brother and cousins had met an awful death at the hands of a mob. Who of my readers would like to be tried under these circumstances? On that jury that tried me sat six men whom I knew to be directly implicated in my brother's death. No, my readers, I have served twenty-five years for the killing of Webb, but know ye that there is a God in high heaven who knows that I did not shoot Charles Webb through malice, nor through anger, nor for money, but to save my own life.

True, it is almost as bad to kill as to be killed. It drove my father to an early grave; it almost distracted my mother; it killed my brother Joe and my cousins Tom and William; it left my brother's widow with two helpless babes; Mrs. Anderson lost her son Ham, and Mrs. Susan Barrickman lost her husband, to say nothing of the grief of countless others. I do say, however, that the man who does not

exercise the first law of nature - that of self preservation - is not worthy of living and breathing the breath of life.

The jury gave me twenty-five years in the penitentiary and found me guilty of murder in the second degree. I appealed the case. The Rangers took me back to Austin to await the result of my appeal. Judge White affirmed the decision of the lower court, and they took me back to Comanche in the latter part of September, 1878, where I received my sentence of twenty-five years with hard labor.

(9) John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin as Written by Himself (1896)

After receiving my sentence at Comanche, they started with me to Huntsville, shackled to John Maston, a blacksmith of Comanche convicted of attempting to murder and under two years' sentence. This man afterwards committed suicide by jumping from the upper story in the building to a Rock floor, where he was dashed to pieces. Nat Mackey, who was sentenced for seventeen years for killing a man with a rock, was chained to Davenport, who had a sentence of five years for horse stealing. Thus there were four prisoners chained-by two's in a wagon and guarded by a sheriff and company of Rangers. Of course, great crowds would flock from everywhere to see the notorious John Wesley Hardin, from the hoary-headed farmer to the little maid hardly in her teens.

On one occasion a young lady told me she had come over to where we were passing the day before and would not have missed seeing me for $100. I asked her if she was satisfied now. She said, "Oh, yes; I can tell everybody I have seen the notorious John Wesley Hardin, and he is so handsome!"

(10) John Wesley Hardin, letter to his wife (July, 1881)

It is now about 8 o'clock p.m. and I am locked into my cell for the night. By special permission from my keeper I now write you. I can tell you that I spent this day in almost perfect happiness, as I generally spend the Sabbaths here, something that I once could not enjoy because I did not know the causes or results of that day. I had no idea before how it benefits a man in my condition. Although we are all prisoners here we are on the road to progress. "J. S." and I are both members of our societies and we are looked upon as the leaders by our associates, of which we have a goodly number. John is president of the Moral and Christian Society and I am secretary of our Debating Club. I spoke in our debating club this evening on the subject of Woman's Rights. John held that women should have equal rights with men and I held they shouldn't. We had a lively time. I followed him, winding up the debate for the day. John is the champion of woman's rights, but he failed to convince the judges, who after they had listened to my argument, decided in my favor," etc.

(11) Judge W. S. Fry, pardon sent to John Wesley Hardin (February, 1894)

Enclosed I send you a full pardon from the Governor of Texas. I congratulate you on its reception and trust that it is the day dawn of a bright and peaceful future. There is time to retrieve a lost past. Turn your back upon it with all its suffering and sorrow and fix your eyes upon the future with the determination to make yourself an honorable and useful member of society. The hand of every true man will be extended to assist you in your upward course and I trust that the name of Hardin will in the future be associated with the performance of deeds that will ennoble his family and be a blessing to humanity. Did you ever read Victor Hugo's masterpiece, "Les Miserables"? If not, you ought to read it. It paints in graphic words the life of one who had tasted the bitterest dregs of life's cup, but in his Christian manhood rose above it almost like a god and left behind him a path luminous with good deeds. With the best wishes for your welfare and happiness.

(12) J. Marvin Hunter met John Wesley Hardin in Mason, Texas, in 1895.

John Wesley Hardin came into the office to get an estimate on the cost of printing a small book, the story of his turbulent life. At that time Hardin was forty-two years old, about five feet ten inches in height, weighed about 160 pounds, and wore a heavy mustache. He was of light complexion and had mild blue eyes.

(13) El Paso Times (7th April, 1895)

Among the leading citizens of Pecos City now in El Paso is John Wesley Hardin, a leading member of the Pecos City bar. In his younger days he was as wild as the broad western plains on which he was raised. But he was a generous, brave-hearted youth and got into no small amount of trouble for the sake of his friends, and soon gained the reputation for being quick-tempered and a dead shot.

In those days when one man insulted another, one of the two of them died then and there. Young Hardin, having a reputation for being a very brave man who never took water, was picked out by every bad man who wanted to make a reputation, and that was where the "bad men" made their mistake, for the young westerner still survives many warm and tragic encounters.

Forty-one years has steadied the impetuous cowboy down to a peaceable, dignified, quiet man of business. But underneath his dignity is a firmness that never yields except to reason and law. He is a man who makes friends of all who come into close contact with him.

He is here as associate attorney for the persecution in the case of the State of Texas vs Bud Frazer, charged with assault with intent to kill. Mr. Hardin is known all over Texas. He was born and raised in this state.

(14) Fank Patterson, statement by the bartender of the Acme Saloon (August, 1895)

My name is Frank Patterson. I am a bar tender at present at the Acme saloon. This evening about 11 o'clock J. W. Hardin was standing with Henry Brown shaking dice and Mr. Selman walked in at the door and shot him. Mr. G. L. Shackleford was also in the saloon at the time the shooting took place. Mr. Selman said something as he came in at the door. Hardin was standing with his back to Mr. Selman. I did not see him face around before he fell or make any motion. All I saw was that Mr. Selman came in the door, said something and shot and Hardin fell. Don't think Hardin ever spoke. The first shot was in the head.

(15) El Paso Herald (20th August, 1895)

Last night between 11 and 12 o'clock San Antonio street was thrown into an intense state of excitement by the sound

of four pistol shots that occurred at the Acme saloon. Soon the crowd surged against the door, and there, right inside, lay the body of John Wesley Hardin, his blood flowing over the floor and his brains oozing out of a pistol shot wound that had passed through his head. Soon the fact became known that John Selman, constable of Precinct No. 1, had fired the fatal shots that had ended the career of so noted a character as Wes Hardin, by which name he is better known to all old Texans. For several weeks past trouble has been brewing and it has been often heard on the streets that John Wesley Hardin would be the cause of some killing before he left the town.

Only a short time ago Policeman Selman arrested Mrs. McRose, the mistress of Hardin, and she was tried and convicted of carrying a pistol. This angered Hardin and when he was drinking he often made remarks that showed he was bitter in his feelings towards John Selman. Selman paid no attention to these remarks, but attended to his duties and said nothing. Lately Hardin had become louder in his abuse and had continually been under the influence of liquor and at such times he was very quarrelsome, even getting along badly with some of his friends. This quarrelsome disposition on his part resulted in his death last night and it is a sad warning to all such parties that the rights of others must be respected and that the day is past when a person having the name of being a bad man can run rough shod over the law and rights of other citizens.