Texas Rangers

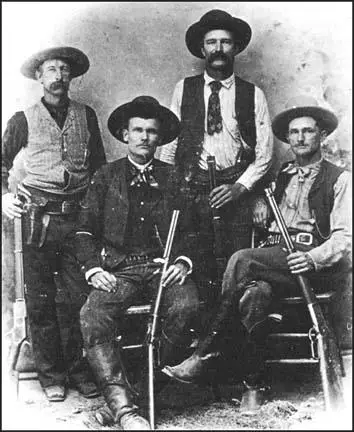

In 1822 Stephen Austin established the first legal Anglo-American colony in Texas. Austin hired a band of horsemen to range over the country to scout the movements of hostile Native Americans. In 1835 this band of men became known as the Texas Rangers. They wore no uniform, never drilled or saluted their officers, and accepted a leader only if he proved the best during combat.

Members of the Texas Rangers included Charles Goodnight,John Coffee Hays and William Wallace. In 1840 Hays was promoted to the rank of captain. He arranged for his men to be given colt revolvers. The Comancheswere used to fighting against men armed with single-shot guns and suffered heavy casualties at Plum Creek (1840), Enchanted Rock (1841) and at Bandera Pass (1842).

A fellow ranger, Nelson Lee, described Hays as "a slim, slight, smooth-faced boy, not over twenty years of age, and looking younger than he was in fact. In his manners he was unassuming in the extreme, a stripling of few words, whose quiet demeanor stretched quite to the verge of modesty. Nevertheless, it was this youngster whom the tall, huge-framed brawny-armed campaigners hailed unanimously as their chief and leader."

In 1850 William Wallace, who had fought under Hays during the Mexican War, was given command of his own company of the Texas Rangers and over the next few years fought against Native Americans and Mexican bandits. He was also active in protecting Texans from war parties and soldiers from the Union Army during the American Civil War.

In 1874 the Texas Rangers were divided into two units. The Frontier Battalion were used against Native Americans attacking settlers, whereas the Special Force attempted to deal with rustlers and robbers in Texas.

The Special Force was disbanded in 1881. Later the Texas Rangers became the Texas Department of Public Safety.

Primary Sources

(1) Nelson Lee, Three Years Among the Comanches (1859)

At the time of my arrival in Texas, the country was in an unsettled state. For a long period of time a system of border warfare had existed between the citizens of Texas and Mexico, growing out of the declaration of independence on the part of the young republic. Marauding parties from beyond the Rio Grande kept the settlers of western Texas in a state of constant agitation and excitement. Besides these annoyances, the inhabitants of other sections were perpetually on the alert to defend themselves against those savage tribes which roamed over the vast region to the north, and which, not infrequently, stole down among the settlers, carrying away their property and putting them to death.

This condition of affairs necessarily resulted in bringing into existence the Texas Rangers, a military order as peculiar as it has become famous. The extensive frontier exposed to hostile inroads, together with the extremely sparse population of the country, rendered any other force of comparatively small avail. The qualifications necessary in a genuine Ranger were not, in many respects, such as are required in the ordinary soldier. Discipline, in the common acceptation of the term, was not regarded as absolutely essential. A fleet horse, an eye that could detect the trail, a power of endurance that defied fatigue, and the faculty of "looking through the double sights of his rifle with a steady arm," - these distinguished the Ranger, rather than any special knowledge of tactics. He was subjected to no "regulation uniform," though his usual habiliments were buckskin moccasins and overhauls, a roundabout and red shirt, a-cap manufactured by his own hands from the skin of the coon or wildcat, two or three revolvers and a bowie knife in his belt, and a short rifle on his arm. In this guise, and well mounted, should he measure eighty miles between the rising and setting sun, and then, gathering his blanket around him, lie down to rest upon the prairie grass with his saddle for a pillow, it would not, at all, occur to him he had performed an extraordinary day's labour.

(2) William Wallace, The Adventures of Fig Foot Wallace, The Texas Ranger (1870)

In the fall of 1842, the Indians were worse on the frontiers than they had ever been before, or since. You could not stake a horse out at night with any expectation of finding him the next morning, and a fellow's scalp was not safe on his head five minutes, outside of his own shanty. The people on the frontiers at last came to the conclusion that something had to be done, or else they would be compelled to fall back on the "settlements," which you know would have been reversing the natural order of things. So we collected together by agreement at my ranch, organized a company of about forty men, and the next time the Indians came down from the mountains (and we had not long to wait for them) we took the trail, determined to follow it as long as our horses would hold out.

The trail led as up toward the headwaters of the Llano, and the third day out, I noticed a great many "signal smokes" rising up a long ways off in the direction we were travelling. These "signal smokes" are very curious things anyhow. You will see them rise up in a straight column, no matter how hard the wind may fee blowing, and after reaching a great height, they will spread out at the top like an umbrella, and then, in a minute or so, puff! they are all gone in the twinkling of an eye. How she Indians make them, I never could learn, and I have often asked old frontiersmen if they could tell me, but none of them could ever give me any information on the subject. Even the white men who have been captured by the Indians, and lived with them for years, never learned how these "signal smokes" were made.

(3) Nelson Lee , Three Years Among the Comanches (1859)

There are few readers in this country, I venture to conjecture, whose ears have not become familiar with the name of Jack Hays. It is inseparably connected with the struggle of Texas for independence, and will live in the remembrance of mankind so long as the history of that struggle shall survive. In the imagination of most persons he undoubtedly figures as a rough, bold giant, bewhiskered like a brigand, and wielding the strength of Hercules. On the contrary, at the period of which I write, he was a slim, slight, smooth-faced boy, not over twenty years of age, and looking younger than he was in fact. In his manners he was unassuming in the extreme, a stripling of few words, whose quiet demeanor stretched quite to the verge of modesty. Nevertheless, it was this youngster whom the tall, huge-framed brawny-armed campaigners hailed unanimously as their chief and leader when they had assembled together in their uncouth garb on the grand plaza of Bexar. It was a compliment as well deserved as it was unselfishly bestowed, for young as he was, he had already exhibited abundant evidence that, though a lamb in peace, he was a lion in war; and few, indeed, were the settlers, from the coast to the mountains of the north, or from the Sabine to the Rio Grande, who had not listened in wonder to his daring, and gloried in his exploits.