Adolf Ziegler

Adolf Ziegler, the son of an architect, was born in Bremen on 16th October 1892. He studied at the Weimar Academy from 1910 under Max Doerner at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. As a student he was attracted to modern art, especially expressionism, and the work of Franz Marc. (1)

Ziegler left his studies to serve in the German Army during the First World War. After the war he attended classes by the artist Angelo Jank. He joined the Nazi Party in 1920 and five years later became a friend of Adolf Hitler. Ziegler gradually changed his views on art. He was influenced by the ideas of Paul Schultze-Naumburg, who was strongly opposed to the way women were portrayed by modern artists. (2)

Schultze-Naumburg argued: "Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form... If you want to give a simple and essential meaning to the concept of art, you might say, it is always the expression of man's desire, which is hereby translated into a perceptible form. This putting-in-shape is a creative act, for which the artist forces are necessary... And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art" (3)

In 1933 after Hitler gained power, Ziegler was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. He later became President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of the Cultural Ministry under Joseph Goebbels. (4) At the time Goebbels did not share Ziegler's views on modern art and liked artists such as Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel and Ernst Barlach. As a student at university he had regularly attended lectures in art history. In March 1934 he had served as a honorary patron of an exhibition on Italian Futurism in Berlin. (5) In a speech made in June 1934 Goebbels argued "We National Socialists are not un-modern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters." (6)

Adolf Ziegler and Nazi Art

In January 1934 Hitler had appointed Alfred Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Ziegler got support from Rosenberg in his disagreement with Goebbels. Rosenberg saw his mission to preserve the "folkish ideology in its purest form" and rejected Goebbels's belief that artists such as Heckel, Nolde and Barlach were representative of contemporary Germany's "indigenous Nordic" art. (7)

Adolf Hitler was asked to intervene in the dispute. He made his position clear in a speech in September, 1934. Hitler argued that there were "two dangers" that National Socialism had to overcome. First, the iconoclastic "saboteurs of art," were threatening the development of art in Nazi Germany. "These charlatans are mistaken if they think that the creators of the new Reich are stupid enough or insecure enough to be confused, let alone intimidated, by their twaddle. They will see that the commissioning of what may be the greatest cultural and artistic projects of all time will pass them by as if they had never existed." (8)

Ziegler made all artists join the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. In this way it became possible to prevent artists who were opposed to the policies of the Nazi government from working. For example, Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. However, he was eventually sacked as professor at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. Dix's dismissal letter said that his work "threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves." (9)

Ziegler had been an unknown painter of "lifeless nudity" before Hitler gained power. (10) His style became very popular with other artists and with the general public and his paintings were often sold as postcards. Berthold Hinz has claimed that: "The women become increasingly and more exclusively oriented to the assumed desires of the man finally seem intent on nothing but satisfying those desires. They hope to please him no matter what angle they present to him.... The voyeuristic element peculiar to painting of this period is not one internal to the paintings but one generated in the observer as he contemplates the nude figures... These paintings still granted women the rudiments of sensual power in depicting her coquetry and the exaggerated display of the weapons of her sex. But the 'goddesses' of Ivo Saliger, Adolf Ziegler, and Georg Friendrich are passive creatures that wait submissively to be taken." (11) Ziegler did try to make the nude women more realistic than those produced in antiquity and as a result he was given the nickname of the "Reich Master of Pubic Hair". (12)

In June 1936, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Horrible examples of art Bolshevism have been brought to my attention... I want to arrange an exhibit in Berlin of art from the period of degeneracy. So that people can see and learn to recognize it." (13) By the end of the month he had obtained Hitler's permission to requisition "German degenerate art since 1910" from public collections for the show. Goebbels actually liked modern art and was a collector of the work of Emil Nolde. As Richard J. Evans has pointed out: "Its political opportunism was cynical even by Goebbels's standards. He knew that Hitler's hatred of artistic modernism was unquestionable, and so he decided to gain favour by pandering to it, even though he did not share it himself." (14)

On 27th November, 1936, Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (15)

Ziegler and his entourage, including Goebbels' favourite artist, Hans Schweitzer, toured German galleries and museums and picked out works to be taken to the new exhibition, some museum directors were furious, refused to co-operate, and pleaded with Hitler to obtain compensation if the the confiscated works were sold abroad. Such resistance was not tolerated and some of them lost their jobs. Over a 100 works were seized from the Munich collections, and comparable numbers from museums elsewhere. (16)

The Degenerate Art Exhibition

The Degenerate Art Exhibition organized by Adolf Ziegler and the Nazi Party in Munich took place between 19th July to 30th November 1937. The exhibition presented 650 works of art, confiscated from German museums. The day before the exhibition started, Hitler delivered a speech declaring "merciless war" on cultural disintegration. Degenerate art was defined as works that "insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill". Whereas these artists are "men who are nearer to animals than to humans, children who, if they lived so, would virtually have to be regarded as curses of God." (17)

Ziegler made a speech at the opening of the exhibition. "Our patience with all those who have not been able to fall in line with National Socialist reconstructions during the last four years is at an end. The German people will judge them. We are not scared. The people trust, as in all things, the judgment of one man, our Führer. He knows which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character... What you are seeing here are the crippled products of madness, impertinence, and lack of talent... I would need several freight trains clear our galleries of this rubbish... This will happen soon." (18)

The exhibition included paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 artists. This included work by Kathe Kollwitz, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Paul Klee, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Beckmann, Christian Rohlfs, Oskar Kokoschka, Lyonel Feininger, Ernst Barlach, Otto Müller, Karl Hofer, Max Pechstein, Lovis Corinth, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Willi Baumeister, Kurt Schwitters, Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky.

Visitors found that the works of art were "deliberately badly displayed, hung at odd angles, poorly lit, and jammed up together on the walls, higgledy-piggledy". They carried titles such as Farmers Seen by Jews, Insult to German Womanhood, and Mockery of God. "They were intended to express a congruity between the art produced by mental asylum inmates... and the distorted perspectives adopted by the Cubists and their ilk, a point made explicit in much of the propaganda surrounding the assault on degenerate art as the product of degenerate human beings." (19)

The objective was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them". The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish. Jonathan Petropoulos, the author of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (2014) has pointed out that works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist... The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous." (20) One of the visitors commented: "The artists ought to be tied up next to their pictures, so that every German can spit in their faces - but not only the artists, also the museum directors who, at a time of mass unemployment, poured vast sums into the ever-open jaws of the perpetrators of these atrocities." (21)

The exhibition drew 2,009,899 visitors. After the exhibition closed, the work was confiscated. Among those who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Otto Dix (260), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (22)

Some of the paintings were sold abroad to generate hard cash for the Nazi regime. "The inventory reveals how this cynical process unfolded: they were sold through art dealers trusted by the regime, or they could be exchanged for the kind of racially appropriate artworks displayed in the German Art Exhibition... Artworks which could not be liquidated in this manner were simply destroyed. In March 1939, the Propaganda Ministry had around 5,000 artworks burned in the courtyard of the Berlin Main Fire Department." (23)

Great German Art Exhibition

It was decided to hold a Great German Art Exhibition in Munich. Adolf Ziegler, signed the announcement for the competition. "All German artists in the Reich and abroad" were invited to participate. The only requirement for entering the competition was German nationality or "race". After extending the deadline for submissions, 15,000 works of art were sent in, and of these about 900 were exhibited. According to official records, the exhibition had 600,000 visitors. (24) Hubert Wilm, a pro-Nazi artist, explained what they were trying to achieve: “Representation of the perfect beauty of a race steeled in battle and sport, inspired not by antiquity or classicism but by the pulsing life of our present-day events”. (25)

As Ginny Dawe-Woodings has pointed out: " The communication of values and messages by allegory and metaphor was important but high value was also placed on representations of fitness and well being, as characterizing racial purity and superiority, the Aryan ideal. The identification of the naked man with the ideal of classical beauty and heroism was a ubiquitous sentiment in National Socialist art and popular culture.... Within its unique conservative style Nazi art was purposeful, with content chosen less for aesthetic appeal and more for usefulness in the ‘bigger political picture’. It achieved much in terms of embodying and communicating the wider fascist ethos of the NSDAP: reinforcing its back-story of a pure race and a country with both a mystical past and a great future, a ‘thousand-year Reich’, that would be delivered if the people believed in the ‘quasi-religious’ values of Nazism – military and moral strength together with an intolerance of weakness, liberal values and, above all, the evils and degeneracy of communism and Judaism. It is interesting that the art created was so distinct and clear in its message, such a quintessential fascist aesthetic, that almost seventy years later the material is still something of a taboo with many authors putting disclaimers in their work when discussing Nazi art, seeking to avoid condoning the content." (26)

On the opening day of the First Exhibition of German Art, Munich was covered with Nazi flags. "In the streets perspiring Teuton warriors manhandled a giant sun and carried the tinfoil-covered cosmic ash-tree Yggdrasil (of German legend), in solemn procession... Regaled with these evocations of the past, the crowds entered the exhibition hall and found themselves - back in the past... Every single painting on display projected either soulful elevation or challenging heroism. Cast-iron dignity alternated with idyllic pastoralism. The many rustic family scenes invariably showed entire kinship groups... All the work exhibited transmitted the impression of an intact life from which the stresses and problems of modern existence were entirely absent - and there was one glaringly obvious omission: not a single canvas depicted urban and industrial life." (27)

The art critic, Bruno E. Werner, wrote in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung: "Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body." (28)

The Berliner Illustriere Zeitung commented: "Adolf Wissel's Peasant Group told intimately of the secrets of the German countenance; Karl Leipold's Sailor experienced the sea as creative world-fluidum; Adolf Ziegler's Terpsichore combined a grasp of modern painting with the purity of classical antiquity in its conception of the human body; Elk-Eber's The Last Hand-Grenade showed movingly how the artist had experienced the Great War and given sublime expression to this vision." (29)

The exhibition included Adolf Ziegler's The Four Elements (1937). Adolf Ziegler had been inspired by the words of Alfred Rosenberg, who had highlighted the importance of Greek mythology to the Nazi aesthetic, saying that "The Nordic artist was always inspired by an ideal of beauty. This is nowhere more evident than in Hellas’s powerful, natural ideal of beauty". Ziegler extended the "use of mythology still further, being full depictions of ancient Greek myths in a romantic classical style." (30) Hitler purchased the painting and was eventually hung over his fireplace in his apartment in Munich. (31)

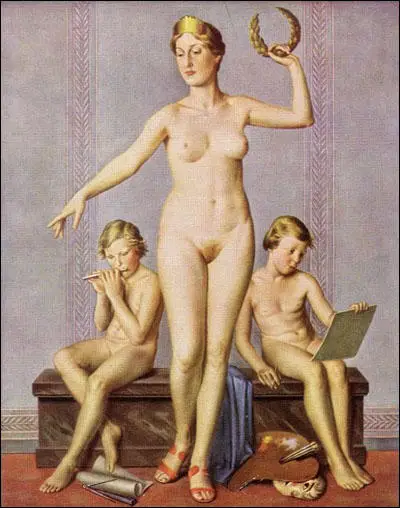

Ziegler entered The Goddess of Art to the 1938 Great German Exhibition. It was described as Ziegler's "painstakingly executed confections of lifeless nudity". (32) Die Kölnische Zeitung was more positive about the painting: "This time it is not Terpsichore but a life-sized Goddess of Art which expresses Ziegler's praise of beautiful nudity. Once again reality has been hit off so accurately that one would think this pink-cheeked female had only a second ago shed the light burden of her clothes. Her nudity, whose careful artistic execution breathes the air of warm life, conceals manifold charms in its opalescent flesh tints." (33)

Frankfurter Zeitung saw the danger to the approach taken by the Nazi government to art: "It may well be that many an artist will no longer have the courage to create anything new after the opening of the House of German Art at Munich". (34) The satirical periodical Simplicissimus added: "There were times when one went to exhibitions and discussed whether the pictures were rubbish, whether the painter knew his job, etc. Now there are no more discussions - everything on the walls is art, and that is that." (35)

The eight exhibitions that were held in the House of German Art in Munich between 1937 and 1944 offered what Ziegler4 considered a valid cross-section of the best artistic efforts from all of Germany. Pageants designed around the theme of a "Day of German Art" took place. Participants wore historical costumes and fancy dress. Hitler gave speeches on "culture" and the entire Nazi Party leadership attended. According to official records, the resulting attendance was as follows: 1937 (600,000), 1938 (460,000), 1939 (400,000), 1940 (600,000), 1941 (700,000) and 1942 (840,000). Allied mass bombing made it difficult to hold these exhibitions after 1942. (36)

In 1943 Ziegler was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned in Dachau Concentration Camp. According to Barbara McCloskey: "He stood accused of behaviour detrimental to the state. While the details of his arrest remain sketchy, it appears that Ziegler may have wavered in his convictions regarding Germany's ability to prevail in the later years of the war... He evidently was also part of a traitors plan to put out feelers for a peace initiative." Hitler, for once showed some compassion and after six weeks personally ordered that he be released and be allowed to retire. (37)

Adolf Ziegler died, aged sixty-seven, on 18th September 1959.

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Schultze-Naumburg, The Struggle for Art (1932)

It is often said that every genuine art reflects the people that originates and sustains it. Obviously, each artist can capture, through his mirror, only a specific part of the character of his people. And yet, it is completely unthinkable that art can live a life of its own and that the beings that appear in front of our eyes are not a true representation of the beings that physically represent a people in the flesh. We know that, from the works of art that the peoples and the times have left us, we can draw a picture of their true spiritual essence, form and environment...

The individual personalities of the artists are too different to reach full overlap. There are those that are tightly oriented to the model and their environment and reproduce it faithfully on the canvas, and those who can only give shape to their dreams of that reality. It does not matter if art is an accurate representation of reality – like it has always been the task of the fine arts - or if it reflects only the times from a spiritual point of view, as a perceptible expression of the substance of reality. After all, one cannot ignore that the higher task of the artist is to show the final objectives to the people of their time, to make visible the image towards which one wishes to move, so that all people could recognize beauty and can start the contest to imitate it and to make themselves compliant with that ideal...

Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form...

We often come across with the opinion that art can produce so many pleasures, introducing the beauty in life. When it comes instead of the most important questions of life, art would have nothing to say. Who thinks so, is not clear on the concept of art and the scale of the task that it has to play in people's lives. Actually, those who think that artistic activity consists of the fact that one is rich enough to buy a French impressionist, in order to display it with pride to friends, capture a very small and not important piece of the whole. If you want to give a simple and essential meaning to the concept of art, you might say, it is always the expression of man's desire, which is hereby translated into a perceptible form. This putting-in-shape is a creative act, for which the artist forces are necessary. The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art.

(2) Adolf Ziegler, speech at the opening of the Degenerate Art Exhibition (19th July, 1937)

Our patience with all those who have not been able to fall in line with National Socialist reconstructions during the last four years is at an end. The German people will judge them. We are not scared. The people trust, as in all things, the judgment of one man, our Führer. He knows which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character... What you are seeing here are the crippled products of madness, impertinence, and lack of talent... I would need several freight trains clear our galleries of this rubbish... This will happen soon.

(3) Völkischer Beobachter (17th July, 1937)

Imbued with the sacred aura of this house and with the historical greatness of this moment, we closed our sublime ceremony with national hymns that resounded like a pledge from the people and its artists to the Führer. At the conclusion of the solemn dedication, the Führer and guests of honour from the diplomatic corps, the government, and the leadership of the NSDAP moved on the large, airy rooms of this new temple of German art to admire the first Great German Art Exhibition.

(4) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

The communication of values and messages by allegory and metaphor was important but high value was also placed on representations of fitness and well being, as characterizing racial purity and superiority, the Aryan ideal. The identification of the naked man with the ideal of classical beauty and heroism was a ubiquitous sentiment in National Socialist art and popular culture....

Within its unique conservative style Nazi art was purposeful, with content chosen less for aesthetic appeal and more for usefulness in the ‘bigger political picture’. It achieved much in terms of embodying and communicating the wider fascist ethos of the NSDAP: reinforcing its back-story of a pure race and a country with both a mystical past and a great future, a ‘thousand-year Reich’, that would be delivered if the people believed in the ‘quasi-religious’ values of Nazism – military and moral strength together with an intolerance of weakness, liberal values and, above all, the evils and degeneracy of communism and Judaism. It is interesting that the art created was so distinct and clear in its message, such a quintessential fascist aesthetic, that almost seventy years later the material is still something of a taboo with many authors putting disclaimers in their work when discussing Nazi art, seeking to avoid condoning the content.

(5) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)

Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body.

(6) Lucy Burns, Degenerate Art: Why Hitler Hated Modernism (2013)

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

The Great German Art Exhibition was designed to show works that Hitler approved of - depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealized soldiers and landscapes.

The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art - modern, abstract, non-representational - or as the Nazis saw it, "degenerate".

The Degenerate Art Exhibition included works by some of the great international names - Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky - along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and Georg Grosz.

The exhibition handbook explained that the aim of the show was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them".

Works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist," says Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and author of several books on art and politics in the Third Reich.

He says the exhibition was laid out with the deliberate intention of encouraging a negative reaction. "The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous."

British artist Robert Medley went to see the show. "It was enormously crowded and all the pictures hung like some kind of provincial auction room where the things had been simply slapped up on the wall regardless to create the effect that this was worthless stuff," he says.

Hitler had been an artist before he was a politician - but the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes that he preferred had been dismissed by the art establishment in favour of abstract and modern styles.

So the Degenerate Art Exhibition was his moment to get his revenge. He had made a speech about it that summer, saying "works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people".

The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the 112 artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish.

The art was divided into different rooms by category - art that was blasphemous, art by Jewish or communist artists, art that criticized German soldiers, art that offended the honour of German women.

One room featured entirely abstract paintings, and was labeled"the insanity room".

"In the paintings and drawings of this chamber of horrors there is no telling what was in the sick brains of those who wielded the brush or the pencil," reads the entry in the exhibition handbook.

The idea of the exhibition was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people.

The curators went to some lengths to get the message across, hiring actors to mingle with the crowds and criticize the exhibits.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich attracted more than a million visitors - three times more than the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibition.

Some realized it could be their last chance to see this kind of art in Germany, while others endorsed Hitler's views. Many people also came because of the air of scandal around the show - and it wasn't just Nazi sympathizers who found the art off-putting.

(7) Jonathon Keats, The Kitschy Triptych That Hung Over Hitler's Fireplace (14th May, 2014)

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

On July 18, 1937, Adolf Hitler opened the first annual Great German Art Exhibition. Housed in the new Haus der Deutsche Kunst in Munich, the show featured new artwork by the Führer's favorite sculptors and painters including Arno Breker and Adolf Ziegler. The work ranged from bombastic to sentimental, glorifying the Third Reich and sanctifying the German Volk. Hardly anybody showed up.

One day later, Ziegler delivered the opening speech for another exhibit down the street. Titled Entartete Kunst – "Degenerate Art" – the show included hundreds of Modernist artworks that Ziegler had confiscated from German museums at Hitler's request. "German Volk, come and judge for yourselves!" Ziegler declared, standing in front of paintings hung helter-skelter, many yanked from their frames for added insult. Over the next four months, more than two million people crowded into the exhibition, which subsequently traveled to eleven more cities in Germany and Austria.

A selection of work from Entartete Kunst is currently on view at the Neue Galerie in Manhattan, drawing an enormous audience once again. Of course the context is entirely different. What was once staged as an act of ridicule and humiliation – ostracizing artists who showed non-Fascist sentiments such as angst and alienation – has been reconstituted as an astute examination of the historical basis and impact of Nazi anti-Modernism. Major pieces from the Great German Art Exhibition, such as Ziegler's kitschy Four Elements – which eventually hung over Hitler's fireplace – are included for comparison with surviving works by some of the modern masters branded as degenerate, such as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Oskar Kokoschka. (Many of the "degenerate" paintings that were destroyed or lost by the Nazis are represented by empty frames at Neue.)

Predictably, Ziegler's pseudo-Classical nudes cannot compete with Expressionist masterpieces by Beckmann or Kirchner; even if Ziegler were as skilled with paint or creative with color as the leading Expressionists, nostalgic sentimentalism lacks the psychological depth of experienced alienation. Yet the chance to see Beckmann's Departure cannot explain the enormous draw of the Neue exhibition. (After all, The Departure is usually just a few subway stops away, in the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection.) The primary interest of this show is political, much as politics made the 1937 exhibit a blockbuster. For all the difference in context, context still predominates.

(8) Jacques Schuhmacher, The Nazis Inventory of Degenerate Art (June, 2020)

In his opening speech at the German Art Exhibition, Hitler had announced a "ruthless war of cleansing against the last elements of our cultural decomposition". Goebbels decided to use this opportunity to finish the job and clear out the remaining unacceptable artworks that had been missed in the initial sweep. The museums were informed that Adolf Ziegler would now confiscate "the remaining products from our period of decay". This time, the screening process did not have to be rushed, but aimed to be truly comprehensive.

The commission, which now had additional members, visited over 100 museums in 74 cities and confiscated approximately 16,000 works of art. These works of art were shipped to a grain silo in Berlin Köpenick, where they were inventoried on index cards. The next step was their 'liquidation': if they could not be shown in Germany outside the context of 'shaming exhibitions', they could yet be sold abroad to generate cold, hard cash for the Nazi regime. The inventory reveals how this cynical process unfolded: they were sold through art dealers trusted by the regime, or they could be exchanged for the kind of racially appropriate artworks displayed in the German Art Exhibition (such cases were indicated on the inventory with a 'T', for 'Tausch', meaning 'exchange'). Artworks which could not be liquidated in this manner were simply destroyed.

In March 1939, the Propaganda Ministry had around 5,000 artworks burned in the courtyard of the Berlin Main Fire Department. It can therefore be assumed that the list in the V&A was created as a final document providing an overview of the outcome of the 'Cleansing of the Temple of Art'. As such, it stands as a memorial for a museum landscape that would never be the same again. The 'liquidation' ended in July 1941.

(9) Nausikaä El-Mecky, Art in Nazi Germany (9th August, 2015)

Hitler loathed Expressionism and modern art whilst pastoral idylls were not serious enough. Goebbels reversed himself and became one of the driving forces behind the Degenerate Art Exhibition, prosecuting the same artworks he had once enjoyed. Rosenberg also let go, albeit reluctantly, whilst Himmler changed tack and stole artworks by the wagonload behind Hitler’s back throughout the war.

Take for example Adolf Ziegler, who had been in charge of selecting the artwork to be exhibited in the Great Exhibition of German Art. Just before the show opened, Hitler visited in order to inspect the artwork chosen to represent the eternal future of Nazi Germany. He was not pleased with the selection his most loyal followers had made. On the 5th of June, 1937, Goebbels wrote in his diary that the Führer was “wild with rage” and subsequently issued a statement declaring “I will not tolerate unfinished paintings,” meaning that the exhibition had to be reconceived at the last minute.

Even opportunistic “hard-liners” like Adolf Ziegler, an artist favored by Hitler, were not quite able to fulfill their patron's vision. However, it would not be right to conclude that the criteria for art that represented the "Aryan" state appears to have been based principally on the eye of Adolf Hitler rather than a set of delineated characteristics. Even Hitler’s taste was not the ultimate indicator of "Aryan" art: whilst planning what great artworks he would take from the conquered museums of Europe for his never-realized Führer-Museum, he was convinced by his newly appointed museum director that his taste was not up to standard for the world-class museum he envisaged. Rather than firing the man, Hitler deferred to this Dr. Hans Posse, despite the fact that he had recently been fired from his post as museum director in Dresden for endorsing "degenerate art."

(10) David Simkin, The Nude Paintings of Adolf Ziegler (8th June, 2020)

Adolf Ziegler was a competent and technically proficient painter, but he is now regarded as an example of a “bad, good artist”. By looking at his paintings we can see how easily, under a totalitarian system, a “good artist” could create “bad art”.

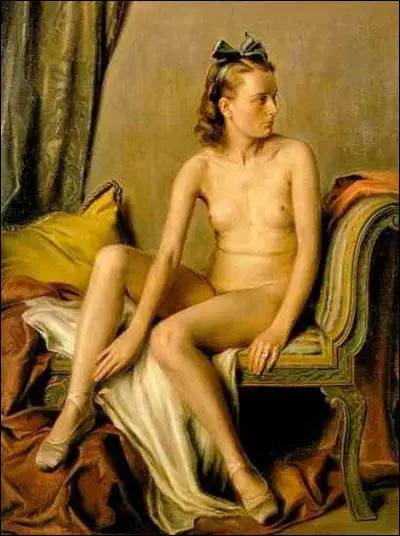

Seated Female Nude (1942)

I would argue that Ziegler’s Seated Female Nude (1942) is not an example of fascistic art. It is, in a technical sense, an accomplished painting, in that the woman’s skin, hair, the ribbon in her hair, the fabrics, the drapes, the cushion, the upholstery etc. are rendered naturalistically and convincingly in oil paint. It is a highly polished work; a painted version of the sort of nude figure that would be captured in a life-drawing class. Ziegler’s Seated Female Nude is an academic piece, reminiscent of the icy Neo-Classical paintings of Jacques-Louis David. To my eye, the nude figure is neither erotic nor representative of the "Aryan ideal" of female beauty. In this particular art work, I can admire Ziegler’s technical skill as a painter, yet I would describe the picture as cold, vapid, anaemic, lifeless and insipid. However, I would suggest that the painting is not particularly supportive of Nazi ideology. The woman in the picture, although suitably Germanic (fair-haired), looks like a real person – the blue ribbon in her hair provides a hint of individuality – and is far removed from the Fascistic aesthetic of some of Ziegler’s earlier works dating from the 1930s (see below). By 1942, when this painting was completed, Ziegler had become disillusioned by the Nazi project - in 1943 he was actually arrested and sent to the Dachau concentration camp on charges of “defeatism”. I suspect that this study of a nude woman was painted for his own artistic satisfaction rather than in service of the Nazi regime.

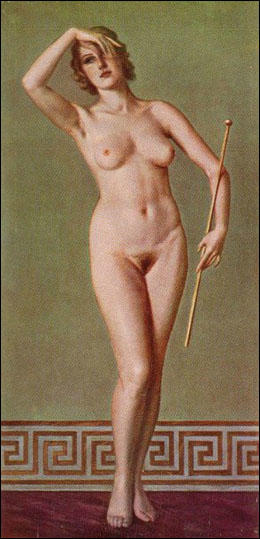

Terpsichore (c. 1935)

Adolf Ziegler’s painting Terpsichore was exhibited at ‘The Great German Art Exhibition’ in Munich in 1937. In Greek mythology, Terpsichore was one of the nine ‘Muses’ – the goddess of dance. The name ‘Terpsichore’ means “delight in dancing” and as a ‘muse’, the goddess Terpsichore was expected to provide the necessary inspiration for the creation of dance. For a painting which is supposed to represent the pleasure of dancing, Ziegler’s Terpsichore is strangely static, rigid and joyless. With very little movement in the picture, I feel that Ziegler’s painting has very little to do with the joy of dancing. ‘Terpsichore’ simply gave Ziegler the intellectual excuse to paint yet another statuesque nude woman. The actual title ‘Terpsichore’ lent Ziegler some much needed “highbrow” credibility – the classical reference drawing attention away from the fact that the painting is essentially “soft porn”.

Like many of Ziegler’s paintings from the 1930s, Terpsichore is a peculiar hybrid of an idealised figure from Classical antiquity with a ‘realist’ representation of a healthy German woman with a beautiful body. Not so much a representation of the perfect “Aryan ideal” of feminine beauty as a Germanic ‘pin-up’. I presume that the large scale of the painting would give the picture a certain statuesque monumentality. If the picture of Terpsichore was only 6 inches high, it would take on the character of a “smutty postcard”. Ziegler’s Terpsichore is like a humourless, realist version of the fanciful ‘pin-up’ nudes painted by K.O. Munson, Gil Evgren, Alberto Vargas and others in the United States in the years leading up to the Second World War. Ziegler’s intention might have been to produce a serious work of art typifying German ideas of feminine beauty, yet the resulting pseudo-classical nude is rather ridiculous. A mature drum majorette stripped of her clothing.

The Four Elements (c. 1936)

Ziegler’s triptych The Four Elements was exhibited at ‘The Great German Art Exhibition’ held in Munich in 1937. The three panels of the Ziegler’s painting depict ‘The Four Elements’ viz. Fire, Water, Earth and Air. The left-hand panel shows a naked young woman holding and shielding a flaming torch (the element of ‘Fire’). The central panel includes a young nude blonde cradling in her hands a silver bowl which contains the second element, “Water”, and a more mature woman, naked except for a white sheet on her lap, grasps a sheaf of wheat, which represents the produce of the soil (‘Earth’). The third panel, which is supposed to signify “Air”, presents more of a challenge to Ziegler and, without a suitable or appropriate symbol, he shows the naked young woman having the tresses of her hair fluttering in what we can only presume is a light breeze. This time, Ziegler, instead of using a single nude figure, has employed the services of four naked models. Although the unclothed bodies represent ideals of Nordic beauty, the faces of the four nudes have been modelled by recognisable individuals. The figure on the right, signifying “Air”, was a young woman named Liselotte, who appears in other Ziegler paintings e.g. Liselotte, Study of a Head (1937). The bare-breasted figure holding the sheaf of cereal can be identified with another named Ziegler model, a woman named Herta.

As in other Ziegler paintings, the materials (the fabrics, the stone plinths and the black & white tiles) have been rendered with skill. The four nude women have been painted with almost ‘photo-realist’ accuracy, but care has been taken to ensure that the naked bodies do not display any imperfections or flaws. By entitling the painting The Four Elements, Ziegler is again referring back to the Classical World, alluding to the writings of Ancient Greek philosophers such as Empedocles and Aristotle. Ziegler has aimed to produce an artwork which implies high culture and classical learning but the overall impression given by the painting is that of kitsch.

Appropriately, kitsch is a German word which can be translated as “rubbish” or “trash”. When used to describe an artefact, kitsch is often associated with sentimentality and notions of popular taste (e.g. a garishly painted plaster ornament depicting a cute kitten), but in the world of "High Art", especially the art which is promoted by a totalitarian regime, the term "kitsch" can take on a different meaning. Catherine A. Lugg, a Professor of Education, has made a study of kitsch in "public art" and has examined how "kitsch art" has been employed by political forces (such as totalitarian regimes) to shape public opinion and understanding. Catherine Lugg has coined the term ‘political kitsch’ to describe this type of art. Lugg claims that ‘political kitsch’ has the “ability to build and exploit cultural myths”.

Milan Kundera, an author who lived under a ‘Communist’ regime in Czechoslovakia during the 1950s and 1960s, has written about what he describes as "totalitarian kitsch", maintaining that kitsch is "the aesthetic ideal of all politicians and all political parties and movements". Kundera provides a useful definition of "totalitarian kitsch": "an aesthetic ideal" which "excludes everything from its purview which is essentially unacceptable in human existence". Under the Nazi regime in Germany, those in power ensured that everything which was deemed unacceptable (ugliness, social ills, poverty, hunger, lust, anxiety, alienation, criticism, expressionistic, unnatural colours and forms, abstract, non-representational art, etc.) were removed from ‘German Art’. The visual art that met with Nazi disapproval was branded as “degenerate”.

Walter Benjamin, the famous art theorist who fled Nazi Germany, argued that ‘Kitsch art’ is a ‘utilitarian object’ which "offers instantaneous emotional gratification without intellectual effort.” Roger Scruton (the conservative philosopher who died earlier this year) made a similar point, claiming that ‘kitsch’ is “fake art, expressing fake emotions, whose purpose is to deceive the consumer into thinking he feels something deep and serious." Catherine Lugg defines ‘kitsch’ as “art that engages the emotions and deliberately ignores the intellect, and as such, is a form of cultural anaesthesia”.

Ziegler’s pseudo-classical nudes, as represented in works such as The Four Elements (c. 1936), The Goddess of Art (1938) and The Judgement of Paris (1939), were an escape from messy, everyday reality. Ziegler employed a romantic classical style to appeal to popular tastes in art. Although Ziegler’s paintings are often adorned with Classical references and symbols, the spectator can immediately recognise the forms in the picture and appreciate the skill of the artist in rendering flesh, woven fabrics and solid stone material. Ziegler’s naturalistic paintings are designed to appeal to the general public, who are often suspicious or resentful towards the extremes of ‘Modern Art’.

Although expertly painted, The Four Elements is devoid of true artistic merit, veering close to the modern concept of ‘camp’ (ostentatious posturing). The painting may contain four nude women, but the waxy bodies are unreal and definitely not erotic. As the four nudes represent the four elements of the Classical World, their nakedness becomes palatable and acceptable. One of the characteristics of ‘political’ or ‘totalitarian’ kitsch is its narrowly traditional approach to art and its tendency to look back to the distant past for its exemplars. Ziegler, like other Nazi artists slavishly copied Classical models. The 20th Century Austrian writer Hermann Broch argued that “the essence of kitsch is imitation”.

Ziegler’s paintings are unchallenging, non-thought provoking, bland and superficial. Ziegler’s ‘political kitsch’ is intended to satisfy the masses, not challenge the individual. As Catherine Lugg points out in her book on state-sponsored ‘political kitsch’, “manufacturers of kitsch are aware of a given audience’s cultural biases and deliberately exploit them, engaging emotions and deliberately ignoring the intellect”. Roger Scruton, in his examination of ‘kitsch art’, argued that such works evoke no authentic emotional reaction, concluding that “you can’t take them seriously, even though seriously is the only way they can be taken if they are taken at all”. Eight-four years after Ziegler’s triptych was completed, the modern observer cannot take The Four Elements seriously. Without the context of Nazi ideology, which imposed its own standards of “natural beauty” and harked back to the ideals of the Classical World, modern eyes can only find Ziegler’s perfectly executed paintings as ridiculous and laughable.

The main purpose of the Ziegler’s work was to reinforce Nazi ideas of what constitutes “pure, wholesome German Art” (as opposed to the characteristics of ‘Modern Art’ which Hitler and Goebbels, and Ziegler himself, had branded as “degenerate”). To modern eyes, Ziegler’s paintings appear innocuous, but when they were produced all those years ago in Nazi Germany they served a more sinister aim – to shape and limit the thinking of the general populace.

Student Activities

References

(1) Barbara McCloskey, Artists of World War II (2005) page 64

(2) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) page 151

(3) Paul Schultze-Naumburg, The Struggle for Art (1932) pages 3-4

(4) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) page 8

(5) Ralf Georg Reuth, The Life of Joseph Goebbels: The Mephistophelian Genius of Nazi Propaganda (1993) page 226

(6) Peter Adam, Art of the Third Reich (1992) page 56

(7) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) page 34

(8) Adolf Hitler, speech at Nuremberg (5th September, 1934)

(9) Linda F. McGreevy, Humanities Magazine (November/December, 2002) page 15

(10) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 538

(11) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) pages 153-154

(12) Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2005) page 171

(13) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (June, 1936)

(14) Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2005) page 171

(15) Frederic Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics (2002) pages 151–168

(16) Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2005) page 171

(17) Adolf Hitler, speech in Munich (18th July, 1937)

(18) Adolf Ziegler, speech at the opening of the Degenerate Art Exhibition (19th July, 1937)

(19) Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2005) page 171

(20) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) pages 38-40

(21) Frankfurter Zeitung (18th August 1937)

(22) Peter Adam, Art of the Third Reich (1992) page 52

(23) Jacques Schuhmacher, The Nazis Inventory of Degenerate Art (June, 2020)

(24) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) pages 8-9

(25) Peter Adam, Art of the Third Reich (1992) page 179

(26) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

(27) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 537

(28) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)

(29) The Berliner Illustriere Zeitung (27th Febuary, 1937)

(30) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

(31) Jonathon Keats, The Kitschy Triptych That Hung Over Hitler's Fireplace (14th May, 2014)

(32) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 539

(33) Die Kölnische Zeitung (17th July, 1938)

(34) Frankfurter Zeitung (8th October 1937)

(35) Simplicissimus (25th February, 1940)

(36) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) pages 1-2

(37) Barbara McCloskey, Artists of World War II (2005) page 65

John Simkin