Great German Art Exhibition

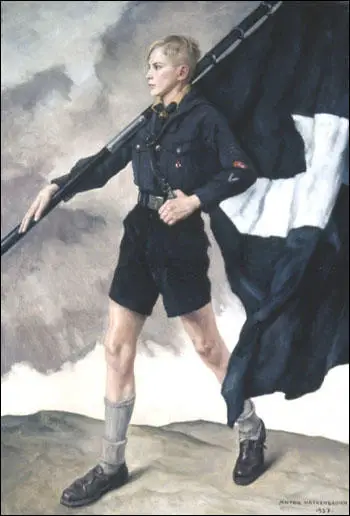

It was decided to hold a Great German Art Exhibition in Munich. Adolf Ziegler, signed the announcement for the competition. "All German artists in the Reich and abroad" were invited to participate. The only requirement for entering the competition was German nationality or "race". After extending the deadline for submissions, 15,000 works of art were sent in, and of these about 900 were exhibited. According to official records, the exhibition had 600,000 visitors. (1) Hubert Wilm, a pro-Nazi artist, explained what they were trying to achieve: “Representation of the perfect beauty of a race steeled in battle and sport, inspired not by antiquity or classicism but by the pulsing life of our present-day events”. (2)

Ziegler was heavily influenced by the ideas of Paul Schultze-Naumburg, who had published a pamphlet entitled, The Struggle for Art (1932): "We know that, from the works of art that the peoples and the times have left us, we can draw a picture of their true spiritual essence, form and environment... After all, one cannot ignore that the higher task of the artist is to show the final objectives to the people of their time, to make visible the image towards which one wishes to move, so that all people could recognize beauty and can start the contest to imitate it and to make themselves compliant with that ideal... Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form... The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art." (3)

On the opening day of the First Exhibition of German Art, Munich was covered with Nazi flags. "In the streets perspiring Teuton warriors manhandled a giant sun and carried the tinfoil-covered cosmic ash-tree Yggdrasil (of German legend), in solemn procession... Regaled with these evocations of the past, the crowds entered the exhibition hall and found themselves - back in the past... Every single painting on display projected either soulful elevation or challenging heroism. Cast-iron dignity alternated with idyllic pastoralism. The many rustic family scenes invariably showed entire kinship groups... All the work exhibited transmitted the impression of an intact life from which the stresses and problems of modern existence were entirely absent - and there was one glaringly obvious omission: not a single canvas depicted urban and industrial life." (4)

The art critic, Bruno E. Werner, wrote in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung: "Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body." (5)

The Berliner Illustriere Zeitung commented: "Adolf Wissel's Peasant Group told intimately of the secrets of the German countenance; Karl Leipold's Sailor experienced the sea as creative world-fluidum; Adolf Ziegler's Terpsichore combined a grasp of modern painting with the purity of classical antiquity in its conception of the human body; Elk-Eber's The Last Hand-Grenade showed movingly how the artist had experienced the Great War and given sublime expression to this vision." (6)

In 1937 Elk Eber showed The Last Grenade at the Great German Exhibition. The following year he exhibited his most famous painting, This Was the SA. " Eber's composition who was the SA was exhibited in Munich showing a march of a SA troop under a swastika banner, a man in the foreground with his head bandaged, and curious onlookers on the side, among them an admiring young boy - in what was most certainly to be a Berlin Communist stronghold in the last republic." (7) Hitler was so impressed with the painting he purchased it for 12,000 RM. (8) Over the next few years a total of 16 of his oil paintings were shown at the annual Great German Art Exhibition. (9)

Another artist featured in the exhibition was Hermann Otto Hoyer. This included his Hitler In the Beginning was the Word (1937): "Here Hitler can be seen haranguing a small crowd seated in a dark room in Oberstdorf, Upper Bavaria, where the rookie politician, historically correct, proselytizes for the nascent NSDAP in the very early 1920s. In front of a swastika flag and flanked by an archetypal storm trooper, Hitler dressed in a simple suit and tie, gesticulates effectively, with onlookers captive - among them, the closest, a woman." (10)

The exhibition included Adolf Ziegler's The Four Elements (1937). Ziegler had been inspired by the words of Alfred Rosenberg, who had highlighted the importance of Greek mythology to the Nazi aesthetic, saying that "The Nordic artist was always inspired by an ideal of beauty. This is nowhere more evident than in Hellas’s powerful, natural ideal of beauty". Ziegler extended the "use of mythology still further, being full depictions of ancient Greek myths in a romantic classical style." (11) Hitler purchased the painting and was eventually hung over his fireplace in his apartment in Munich. (12)

Adolf Ziegler entered The Goddess of Art to the 1938 Great German Exhibition. It was described as Ziegler's "painstakingly executed confections of lifeless nudity". (13) Die Kölnische Zeitung was more positive about the painting: "This time it is not Terpsichore but a life-sized Goddess of Art which expresses Ziegler's praise of beautiful nudity. Once again reality has been hit off so accurately that one would think this pink-cheeked female had only a second ago shed the light burden of her clothes. Her nudity, whose careful artistic execution breathes the air of warm life, conceals manifold charms in its opalescent flesh tints." (14)

Frankfurter Zeitung saw the danger to the approach taken by the Nazi government to art: "It may well be that many an artist will no longer have the courage to create anything new after the opening of the House of German Art at Munich". (15) The satirical periodical Simplicissimus added: "There were times when one went to exhibitions and discussed whether the pictures were rubbish, whether the painter knew his job, etc. Now there are no more discussions - everything on the walls is art, and that is that." (16)

The eight exhibitions that were held in the House of German Art in Munich between 1937 and 1944 offered what Ziegler4 considered a valid cross-section of the best artistic efforts from all of Germany. Pageants designed around the theme of a "Day of German Art" took place. Participants wore historical costumes and fancy dress. Hitler gave speeches on "culture" and the entire Nazi Party leadership attended. According to official records, the resulting attendance was as follows: 1937 (600,000), 1938 (460,000), 1939 (400,000), 1940 (600,000), 1941 (700,000) and 1942 (840,000). Allied mass bombing made it difficult to hold these exhibitions after 1942. (17)

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Schultze-Naumburg, The Struggle for Art (1932)

It is often said that every genuine art reflects the people that originates and sustains it. Obviously, each artist can capture, through his mirror, only a specific part of the character of his people. And yet, it is completely unthinkable that art can live a life of its own and that the beings that appear in front of our eyes are not a true representation of the beings that physically represent a people in the flesh. We know that, from the works of art that the peoples and the times have left us, we can draw a picture of their true spiritual essence, form and environment...

The individual personalities of the artists are too different to reach full overlap. There are those that are tightly oriented to the model and their environment and reproduce it faithfully on the canvas, and those who can only give shape to their dreams of that reality. It does not matter if art is an accurate representation of reality – like it has always been the task of the fine arts - or if it reflects only the times from a spiritual point of view, as a perceptible expression of the substance of reality. After all, one cannot ignore that the higher task of the artist is to show the final objectives to the people of their time, to make visible the image towards which one wishes to move, so that all people could recognize beauty and can start the contest to imitate it and to make themselves compliant with that ideal...

Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form...

We often come across with the opinion that art can produce so many pleasures, introducing the beauty in life. When it comes instead of the most important questions of life, art would have nothing to say. Who thinks so, is not clear on the concept of art and the scale of the task that it has to play in people's lives. Actually, those who think that artistic activity consists of the fact that one is rich enough to buy a French impressionist, in order to display it with pride to friends, capture a very small and not important piece of the whole. If you want to give a simple and essential meaning to the concept of art, you might say, it is always the expression of man's desire, which is hereby translated into a perceptible form. This putting-in-shape is a creative act, for which the artist forces are necessary. The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art.

(2) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

The communication of values and messages by allegory and metaphor was important but high value was also placed on representations of fitness and well being, as characterizing racial purity and superiority, the Aryan ideal. The identification of the naked man with the ideal of classical beauty and heroism was a ubiquitous sentiment in National Socialist art and popular culture....

Within its unique conservative style Nazi art was purposeful, with content chosen less for aesthetic appeal and more for usefulness in the ‘bigger political picture’. It achieved much in terms of embodying and communicating the wider fascist ethos of the NSDAP: reinforcing its back-story of a pure race and a country with both a mystical past and a great future, a ‘thousand-year Reich’, that would be delivered if the people believed in the ‘quasi-religious’ values of Nazism – military and moral strength together with an intolerance of weakness, liberal values and, above all, the evils and degeneracy of communism and Judaism. It is interesting that the art created was so distinct and clear in its message, such a quintessential fascist aesthetic, that almost seventy years later the material is still something of a taboo with many authors putting disclaimers in their work when discussing Nazi art, seeking to avoid condoning the content.

(3) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)

Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body.

(4) Lucy Burns, Degenerate Art: Why Hitler Hated Modernism (2013)

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

The Great German Art Exhibition was designed to show works that Hitler approved of - depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealized soldiers and landscapes.

The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art - modern, abstract, non-representational - or as the Nazis saw it, "degenerate".

The Degenerate Art Exhibition included works by some of the great international names - Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky - along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and Georg Grosz.

The exhibition handbook explained that the aim of the show was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them".

Works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist," says Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and author of several books on art and politics in the Third Reich.

He says the exhibition was laid out with the deliberate intention of encouraging a negative reaction. "The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous."

British artist Robert Medley went to see the show. "It was enormously crowded and all the pictures hung like some kind of provincial auction room where the things had been simply slapped up on the wall regardless to create the effect that this was worthless stuff," he says.

Hitler had been an artist before he was a politician - but the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes that he preferred had been dismissed by the art establishment in favour of abstract and modern styles.

So the Degenerate Art Exhibition was his moment to get his revenge. He had made a speech about it that summer, saying "works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people".

The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the 112 artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish.

The art was divided into different rooms by category - art that was blasphemous, art by Jewish or communist artists, art that criticized German soldiers, art that offended the honour of German women.

One room featured entirely abstract paintings, and was labeled"the insanity room".

"In the paintings and drawings of this chamber of horrors there is no telling what was in the sick brains of those who wielded the brush or the pencil," reads the entry in the exhibition handbook.

The idea of the exhibition was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people.

The curators went to some lengths to get the message across, hiring actors to mingle with the crowds and criticize the exhibits.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich attracted more than a million visitors - three times more than the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibition.

Some realized it could be their last chance to see this kind of art in Germany, while others endorsed Hitler's views. Many people also came because of the air of scandal around the show - and it wasn't just Nazi sympathizers who found the art off-putting.

(5) Jonathon Keats, The Kitschy Triptych That Hung Over Hitler's Fireplace (14th May, 2014)

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

On July 18, 1937, Adolf Hitler opened the first annual Great German Art Exhibition. Housed in the new Haus der Deutsche Kunst in Munich, the show featured new artwork by the Führer's favorite sculptors and painters including Arno Breker and Adolf Ziegler. The work ranged from bombastic to sentimental, glorifying the Third Reich and sanctifying the German Volk. Hardly anybody showed up.

One day later, Ziegler delivered the opening speech for another exhibit down the street. Titled Entartete Kunst – "Degenerate Art" – the show included hundreds of Modernist artworks that Ziegler had confiscated from German museums at Hitler's request. "German Volk, come and judge for yourselves!" Ziegler declared, standing in front of paintings hung helter-skelter, many yanked from their frames for added insult. Over the next four months, more than two million people crowded into the exhibition, which subsequently traveled to eleven more cities in Germany and Austria.

A selection of work from Entartete Kunst is currently on view at the Neue Galerie in Manhattan, drawing an enormous audience once again. Of course the context is entirely different. What was once staged as an act of ridicule and humiliation – ostracizing artists who showed non-Fascist sentiments such as angst and alienation – has been reconstituted as an astute examination of the historical basis and impact of Nazi anti-Modernism. Major pieces from the Great German Art Exhibition, such as Ziegler's kitschy Four Elements – which eventually hung over Hitler's fireplace – are included for comparison with surviving works by some of the modern masters branded as degenerate, such as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Oskar Kokoschka. (Many of the "degenerate" paintings that were destroyed or lost by the Nazis are represented by empty frames at Neue.)

Predictably, Ziegler's pseudo-Classical nudes cannot compete with Expressionist masterpieces by Beckmann or Kirchner; even if Ziegler were as skilled with paint or creative with color as the leading Expressionists, nostalgic sentimentalism lacks the psychological depth of experienced alienation. Yet the chance to see Beckmann's Departure cannot explain the enormous draw of the Neue exhibition. (After all, The Departure is usually just a few subway stops away, in the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection.) The primary interest of this show is political, much as politics made the 1937 exhibit a blockbuster. For all the difference in context, context still predominates.

(6) Jacques Schuhmacher, The Nazis Inventory of Degenerate Art (June, 2020)

In his opening speech at the German Art Exhibition, Hitler had announced a "ruthless war of cleansing against the last elements of our cultural decomposition". Goebbels decided to use this opportunity to finish the job and clear out the remaining unacceptable artworks that had been missed in the initial sweep. The museums were informed that Adolf Ziegler would now confiscate "the remaining products from our period of decay". This time, the screening process did not have to be rushed, but aimed to be truly comprehensive.

The commission, which now had additional members, visited over 100 museums in 74 cities and confiscated approximately 16,000 works of art. These works of art were shipped to a grain silo in Berlin Köpenick, where they were inventoried on index cards. The next step was their 'liquidation': if they could not be shown in Germany outside the context of 'shaming exhibitions', they could yet be sold abroad to generate cold, hard cash for the Nazi regime. The inventory reveals how this cynical process unfolded: they were sold through art dealers trusted by the regime, or they could be exchanged for the kind of racially appropriate artworks displayed in the German Art Exhibition (such cases were indicated on the inventory with a 'T', for 'Tausch', meaning 'exchange'). Artworks which could not be liquidated in this manner were simply destroyed.

In March 1939, the Propaganda Ministry had around 5,000 artworks burned in the courtyard of the Berlin Main Fire Department. It can therefore be assumed that the list in the V&A was created as a final document providing an overview of the outcome of the 'Cleansing of the Temple of Art'. As such, it stands as a memorial for a museum landscape that would never be the same again. The 'liquidation' ended in July 1941.

(7) Nausikaä El-Mecky, Art in Nazi Germany (9th August, 2015)

Hitler loathed Expressionism and modern art whilst pastoral idylls were not serious enough. Goebbels reversed himself and became one of the driving forces behind the Degenerate Art Exhibition, prosecuting the same artworks he had once enjoyed. Rosenberg also let go, albeit reluctantly, whilst Himmler changed tack and stole artworks by the wagonload behind Hitler’s back throughout the war.

Take for example Adolf Ziegler, who had been in charge of selecting the artwork to be exhibited in the Great Exhibition of German Art. Just before the show opened, Hitler visited in order to inspect the artwork chosen to represent the eternal future of Nazi Germany. He was not pleased with the selection his most loyal followers had made. On the 5th of June, 1937, Goebbels wrote in his diary that the Führer was “wild with rage” and subsequently issued a statement declaring “I will not tolerate unfinished paintings,” meaning that the exhibition had to be reconceived at the last minute.

Even opportunistic “hard-liners” like Adolf Ziegler, an artist favored by Hitler, were not quite able to fulfill their patron's vision. However, it would not be right to conclude that the criteria for art that represented the "Aryan" state appears to have been based principally on the eye of Adolf Hitler rather than a set of delineated characteristics. Even Hitler’s taste was not the ultimate indicator of "Aryan" art: whilst planning what great artworks he would take from the conquered museums of Europe for his never-realized Führer-Museum, he was convinced by his newly appointed museum director that his taste was not up to standard for the world-class museum he envisaged. Rather than firing the man, Hitler deferred to this Dr. Hans Posse, despite the fact that he had recently been fired from his post as museum director in Dresden for endorsing "degenerate art."

Student Activities

References

(1) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) pages 8-9

(2) Peter Adam, Art of the Third Reich (1992) page 179

(3) Paul Schultze-Naumburg, The Struggle for Art (1932) pages 3-4

(4) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 537

(5) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)

(6) The Berliner Illustriere Zeitung (27th Febuary, 1937)

(7) Michael H. Kater, Culture in Nazi Germany (2019) page 112

(8) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) page 13

(9) Galleria Thule Italia, Elk Eber (11th March, 2009)

(10) Michael H. Kater, Culture in Nazi Germany (2019)

(11) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

(12) Jonathon Keats, The Kitschy Triptych That Hung Over Hitler's Fireplace (14th May, 2014)

(13) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 539

(14) Die Kölnische Zeitung (17th July, 1938)

(15) Frankfurter Zeitung (8th October 1937)

(16) Simplicissimus (25th February, 1940)

(17) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1979) pages 1-2