Anton Hackenbroich

Anton Hackenbroich was born in Düsseldorf on 28th December, 1878. He studied painting at the Düsseldorf Art Academy from 1899 to 1907, where he was taught by Ernst Roeber, Willy Spatz and Peter Janssen were his teachers there. Later he studied under Eduard von Gebhardt.

Hackenbroich supported the Nazi Party and he benefited from Adolf Hitler gaining power. On 27th November, 1936, Joseph Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (1)

The Degenerate Art Exhibition organized by Adolf Ziegler and the Nazi Party in Munich took place between 19th July to 30th November 1937. The exhibition presented 650 works of art, confiscated from German museums. The day before the exhibition started, Hitler delivered a speech declaring "merciless war" on cultural disintegration. Degenerate art was defined as works that "insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill". (2)

The exhibition included 650 paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 artists. This included work by Kathe Kollwitz, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Paul Klee, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Beckmann, Christian Rohlfs, Oskar Kokoschka, Lyonel Feininger, Ernst Barlach, Otto Müller, Karl Hofer, Max Pechstein, Lovis Corinth, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Willi Baumeister, Kurt Schwitters, Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky.

The objective was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them". The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish. Jonathan Petropoulos, the author of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (2014) has pointed out that works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist... The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous." (3)

The exhibition drew 2,009,899 visitors. After the exhibition closed, the work was confiscated. Among those who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Otto Dix (260), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (4)

Book burnings were organized, artists and musicians were dismissed from teaching positions, and museum curators were replaced by Party members. (5) Hackenbroich, like all other artists, had to join the Nazi government's Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of Goebbels' Cultural Ministry (Reichskulturkammer). Membership was mandatory for all artists in the Reich. (6)

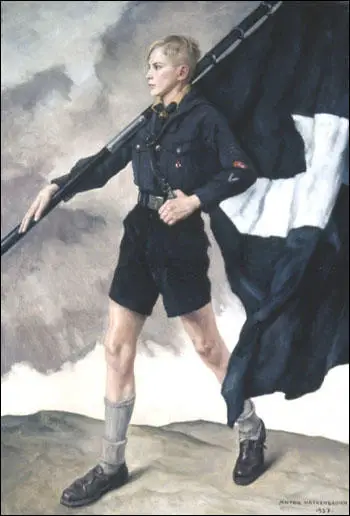

In July, 1937, the Nazi government opened the Great German Art Exhibition in Munich. It was hoped to emphasize the triumph of "art in the Third Reich" over "degenerate" modernism. Anton Hackenbroich was one of the artists whose work was exhibited. According to official records, the exhibition had 600,000 visitors. This compared very badly with the 2,009,899 people (an average of 20,000 a day) who went to the Degenerate Art Exhibition. (7)

The art critic, Bruno E. Werner, wrote in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung: "Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body." (8)

Anton Hackenbroich died in 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) Völkischer Beobachter (17th July, 1937)

Imbued with the sacred aura of this house and with the historical greatness of this moment, we closed our sublime ceremony with national hymns that resounded like a pledge from the people and its artists to the Führer. At the conclusion of the solemn dedication, the Führer and guests of honour from the diplomatic corps, the government, and the leadership of the NSDAP moved on the large, airy rooms of this new temple of German art to admire the first Great German Art Exhibition.

(2) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

Within its unique conservative style Nazi art was purposeful, with content chosen less for aesthetic appeal and more for usefulness in the ‘bigger political picture’. It achieved much in terms of embodying and communicating the wider fascist ethos of the NSDAP: reinforcing its back-story of a pure race and a country with both a mystical past and a great future, a ‘thousand-year Reich’, that would be delivered if the people believed in the ‘quasi-religious’ values of Nazism – military and moral strength together with an intolerance of weakness, liberal values and, above all, the evils and degeneracy of communism and Judaism. It is interesting that the art created was so distinct and clear in its message, such a quintessential fascist aesthetic, that almost seventy years later the material is still something of a taboo with many authors putting disclaimers in their work when discussing Nazi art, seeking to avoid condoning the content.

(3) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)

Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body.

(4) Lucy Burns, Degenerate Art: Why Hitler Hated Modernism (2013)

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

The Great German Art Exhibition was designed to show works that Hitler approved of - depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealised soldiers and landscapes.

The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art - modern, abstract, non-representational - or as the Nazis saw it, "degenerate".

The Degenerate Art Exhibition included works by some of the great international names - Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky - along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and Georg Grosz.

The exhibition handbook explained that the aim of the show was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them".

Works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist," says Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and author of several books on art and politics in the Third Reich.

He says the exhibition was laid out with the deliberate intention of encouraging a negative reaction. "The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous."

British artist Robert Medley went to see the show. "It was enormously crowded and all the pictures hung like some kind of provincial auction room where the things had been simply slapped up on the wall regardless to create the effect that this was worthless stuff," he says.

Hitler had been an artist before he was a politician - but the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes that he preferred had been dismissed by the art establishment in favour of abstract and modern styles.

So the Degenerate Art Exhibition was his moment to get his revenge. He had made a speech about it that summer, saying "works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people".

The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the 112 artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish.

The art was divided into different rooms by category - art that was blasphemous, art by Jewish or communist artists, art that criticised German soldiers, art that offended the honour of German women.

One room featured entirely abstract paintings, and was labelled "the insanity room".

"In the paintings and drawings of this chamber of horrors there is no telling what was in the sick brains of those who wielded the brush or the pencil," reads the entry in the exhibition handbook.

The idea of the exhibition was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people.

The curators went to some lengths to get the message across, hiring actors to mingle with the crowds and criticise the exhibits.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich attracted more than a million visitors - three times more than the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibition.

Some realised it could be their last chance to see this kind of art in Germany, while others endorsed Hitler's views. Many people also came because of the air of scandal around the show - and it wasn't just Nazi sympathisers who found the art off-putting.

Student Activities

References

(1) Joseph Goebbels, decree (27th November, 1936)

(2) Frederic Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics (2002) pages 151–168

(3) Lucy Burns, Degenerate Art: Why Hitler Hated Modernism (2013)

(4) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1977) pages 38-40

(5) Peter Adam, Art of the Third Reich (1992) page 52

(6) Otto Conzelmann, Otto Dix (1959) page 50

(7) Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich (1977) page 1

(8) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)