On this day on 11th February

On this day in 1802 Lydia Maria Francis was born in Medford, Massachusetts. In her twenties Child began to write popular historical novels such as Hobomok (1824) and The Rebels (1825). In 1826 established a periodical for children called Juvenile Miscellany. Her book, The Frugal Housewife (1829), was especially popular with the American public.

After hearing William Lloyd Garrison speak at a public meeting in 1831 Child began involved in the campaign against slavery. This included her book An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans (1833). This book converted people such as Charles Sumner to the cause but upset her traditional readers and sales of her other books dropped dramatically. She was eventually forced to cease publication of Juvenile Miscellany and instead she started with her husband, David Lee Child, a weekly newspaper, the Anti-Slavery Standard.

In 1839 Lydia Maria Child and two other women, Lucretia Mott and Maria Weston Chapman were elected to the executive committee of the Anti-Slavery Society. This upset some members of the society were extremely upset by this decision. Lewis Tappan, the brother of Arthur Tappan, the president of the society, argued that: "To put a woman on the committee with men is contrary to the usages of civilized society."

Whereas one leaders, such as William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld, Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass were as committed to women's rights as they were to the abolition of slavery. Others disagreed with this view and in 1840 a group including Arthur Tappan, James Birney and Gerrit Smith left the Anti-Slavery Society and formed a rival organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1861 Child controversially helped Harriet Jacobs publish Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. At the time the book was condemned because of the way it dealt with the sexual exploitation of young female slaves. Jacobs was also highly critical of the role of the Church in maintaining slavery.

Child also became concerned about the rights of women and Native Americans. This was reflected in the publication of History of the Condition of Woman in Various Ages and Nations and An Appeal for the Indians. Lydia Maria Francis died on 7th July, 1880, in Wayland, Massachusetts.

On this day Hannah Mitchell, the daughter of John Webster, a small farmer in Derbyshire, was born on 11th February 1871. Hannah received only two weeks of formal schooling and was kept busy on the farm and with domestic duties. Her three brothers did not have to work at home and she grew up with a strong awareness of gender inequalities.

At the age of fourteen Hannah had a vigorous row with her mother over the work she was expected to do. After being badly beaten with a stick, Hannah ran away from home. Hannah found work as a dressmaker in Bolton. Although she was only earning eight shillings a week, she managed to subscribe to a small library and over the next few years taught herself to read and write.

While working in Bolton, Hannah met Gibbon Mitchell, a tailor's cutter. Gibbon was the son of a widow with eight children and had worked since the age of ten. Gibbon was a socialist and the couple began attending meetings at the Bolton branch of the Independent Labour Party. Hannah and Gibbon became active in the trade union movement in Bolton during this period and avid readers The Clarion a journal produced by Robert Blatchford.

Hannah married Mitchell in 1895. Hannah insisted that they should share domestic duties. Although he agreed on principal with this, he found it difficult to live up to Hannah's expectations of how a husband should behave. She later pointed out in her autobiography that she gradually realised that "socialists are not necessarily feminists." Hannah also objected to the way her husband "handed over the wages and left all the worrying to me." She wrote that even "the most sympathetic man can never be made to understand that meals do not come up through the tablecloth, but have to be planned, bought and cooked."

In 1904 Hannah joined the local branch of Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Gibbon Mitchell supported her involvement and because of local hostility to the suffragettes was employed as one of the bodyguards at public meetings. Hannah's involvement in the movement grew and in 1905 she became a full-time worker for the WSPU.

Like many of the leading figures in the WSPU, Mitchell objected to the way that Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst made important decisions without consulting fellow members. In 1907 Charlotte Despard persuaded her to join Women's Freedom League.

Mitchell was a pacifist and refused to become involved the WSPU army recruiting campaign in 1914. She joined the Independent Labour Party and other organised that opposed the war including the No-Conscription Fellowship and the Women's Peace Council.

In 1924 Hannah Mitchell was elected to the Manchester City Council. She remained an important political figure in Manchester until she retired. In her seventies Hannah wrote her autobiography The Hard Way Up. Unfortunately, the book was not published until after her death on 22nd October 1956.

On this day in 1911 the Appeal to Reason journal reported on Industrial Workers of the World organizers being imprisoned. "There are about one hundred I.W.W. men in jail now with different charges, but all are arrested for the same offense. Only a few of the I.W.W. men have been tried. Some of the best speakers were tried and convicted of vagrancy, by juries of business men. Four of them got six months apiece, although they proved that they were not vagrants. Many of the boys have been imprisoned for fifty-one days, today, without trial. This happened not in Russia, but in sunny California. Frank Little was arrested on the charge of vagrancy. Frank is one of the 94 I.W.W. men confined in a bull pen, 47 x 28 feet. The officers of the state board of health say that there is air enough in the pen for 5 men. Most of the men confined in the bull pen have been out in the open air only once or twice since they were arrested."

In 1905 representatives of 43 groups who opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour, formed the radical labour organisation, the IWW. The IWW's goal was to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class. Its motto was "an injury to one is an injury to all". At first its main leaders were William Haywood, Vincent Saint John, Daniel De Leon and Eugene V. Debs. Other important figures in the movement included Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Lucy Parsons, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Anna Louise Strong, Joseph Ettor, Arturo Giovannitti, James P. Cannon, William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Joe Haaglund Hill, Tom Mooney, Harry Bridges, Floyd B. Olson, James Larkin, James Connolly, Roger Nash Baldwin, Frank Little and Ralph Chaplin.

Soon after the IWW was formed William Haywood was charged with taking part in the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. Steunenberg was much hated by the trade union movement after using federal troops to help break strikes during his period of office. Over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire.

McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named Hayward and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Charles Darrow, a man who specialized in defending trade union leaders, was employed to defend William Haywood, Charles Moyer and George Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry. During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Haywood, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard and were all acquitted.

Many unions refused to accept immigrant workers. This was especially a problem for Jewish and Irish immigrants. This was not true of the Industrial Workers of the World and as a result many of its members were first and second generation immigrants. Several immigrants such as Mary 'Mother' Jones, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Arturo Giovannitti and Joe Haaglund Hill became leaders of the organization.

In 1908 the Wobblies, as they became known, split into two factions. The group headed by Eugene V. Debs advocated political action through the Socialist Party and the trade union movement, to attain its goals. The other faction led by William Haywood, and believed that general strikes, boycotts and even sabotage to achieve its objectives. Haywood's views prevailed and Debs, and others who thought like him, left the organisation.

Solidarity (4th August, 1917)

On this day in 1914 blacklisted folk singer Josh White was born in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1914. As a child he worked as a guide for a local street-singer, Blind John Henry Arnold. In 1932 White moved to New York City where he obtained a recording contract with ARC and had a great success with songs such as St. James Infirmary Blues and the anti-lynching song, Strange Fruit.

In 1939 White appeared with Paul Robeson in the show John Henry. During the Second World War he performed for the US Office of War Information. These radio programs were broadcast by the BBC and he became very popular in Britain.

After the war the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the entertainment industry. In its first three years the HUAC managed to get a large number of people blacklisted for their political views. On 22nd June, 1950, Theodore Kirkpatrick, a former FBI agent and Vincent Harnett, a right-wing television producer, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organizations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted.

White was one of those named in Red Channels. This became a serious problem when a free copy was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past.

On 1st September, 1950, White appeared before the HUAC. He admitted he had performed at charity concerts with Paul Robeson but argued that he was unaware of the political groups behind them. White claimed that the only communist he knew was Robeson's friend, Benjamin Davis.

However, despite this testimony, Josh White was not removed from the blacklist in the United States. White continued his career as a folk-singer in Europe where his work was published by Vogue (France) and EMI (Britain). White also recorded for Electra (1954-62) and Mercury (1962-4). Josh White died on 5th September, 1969.

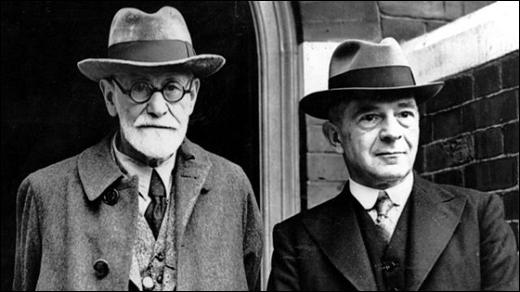

On this day in 1958 psychoanalyst Ernest Jones died. In 1920 Jones founded the International Journal for Psychoanalysis, which was the first English-language periodical devoted to psychoanalysis. He remained its editor for the next nineteen years. In 1924, together with John Rickman, he established the Institute of Psychoanalysis in London. In 1926, thanks to a donation of £10,000 from his patient Prynce Hopkins, the London Clinic of Psycho-Analysis was formed, which enabled low-cost psychoanalytic treatment. Jones became its honorary director. According to his biographer, Sonu Shamdasani: "Thus Jones effectively occupied most of the positions of power in British psychoanalysis, centralizing authority upon himself. In addition to his central role in Britain, Jones was the president of the International Psycho-Analytical Association from 1920 to 1924."

During the Second World War Jones moved to his country house, "The Plat", at Elsted, near Chichester, in semi-retirement, with only a few wealthy patients. After the war he started work on his The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, which appeared in three volumes in 1953, 1955, and 1957. "This was his most significant literary achievement. In preparation for it Jones had unrivalled access to Freud's papers, many of which remain inaccessible to scholars to this day." (50)

Jones was aided by the fact that his wife, Katharina Jokl, was a native German speaker and she transcribed over a thousand letters of Freud for him. His son, Mervyn Jones, pointed out: "I can only affirm, and cannot express as he would have, the degree to which he loved and valued her as a wife, as an unfailing support in times of strain, and as an especially in preparing the Freud biography." (51)

The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud remains the single most important biographical source of information on Freud's life and on the early history of the psychoanalytic movement. No other single work has been more influential in shaping the subsequent perception of Freud. However, Lisa Appignanesi, the author of Freud's Women (1995) has described the book as a "magnificent, if somewhat hagiographical, biography of Freud". (52)

Jones definitely used the book to attack Freud's opponents such as Alfred Adler, Carl Jung and Otto Rank, who were "represented as heretics, whose original ideas stemmed from personal psychopathology and character defects". Whereas his followers "especially Jones himself, were portrayed as a revolutionary vanguard that fought against vicious and malevolent opponents, widespread prejudice, and obscurantism". (53)

In 1956 Ernest Jones contracted cancer of the bladder. Two years later he developed cancer of the liver. He died in University College Hospital on 11th February 1958, and was cremated at Golders Green three days later. At his death he left an uncompleted manuscript of his autobiography. This was edited by his son, Mervyn Jones, and published as Free Associations: Memories of a Psycho-Analyst in 1959.

On this day in 1967 peace activist Abraham J. Muste died. Muste was born in Zierkzee, Holland, on 8th January, 1885. His family moved to the United States in 1891. His father was supporter of the Republican Party and as a young man he shared his conservative views. In 1909 he was ordained a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church.

Muste became increasingly radical and in the 1912 presidential campaign supported Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate. On the outbreak of the First World War Muste left the Dutch Reformed Church and became a pacifist. In 1919 he played an active role in supporting workers during the Lawrence Textile Strike and later moved to Boston where he found work with the American Civil Liberties Union. In the early 1920s Muste worked as director of the Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, Westchester County. He also joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR).

Muste was disturbed by the events that were taking place in the Soviet Union. He no longer felt he could support the policies of Joseph Stalin. Muste now decided to join with other like-minded people to form the American Workers Party (AWP). Established in December, 1933, Muste became the leader of the party and other members included Sidney Hook, Louis Budenz, James Rorty, V.F. Calverton, George Schuyler, James Burnham, J. B. S. Hardman and Gerry Allard.

Hook later argued in his autobiography, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "The American Workers Party (AWP) was organized as an authentic American party rooted in the American revolutionary tradition, prepared to meet the problems created by the breakdown of the capitalist economy, with a plan for a cooperative commonwealth expressed in a native idiom intelligible to blue collar and white collar workers, miners, sharecroppers, and farmers without the nationalist and chauvinist overtones that had accompanied local movements of protest in the past. It was a movement of intellectuals, most of whom had acquired an experience in the labor movement and an allegiance to the cause of labor long before the advent of the Depression."

Soon after its formation of the AWP, leaders of the Communist League of America (CLA), a group that supported the theories of Leon Trotsky, suggested a merger. Sidney Hook, James Burnham and J. B. S. Hardman were on the negotiating committee for the AWP, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern and Arne Swabeck, for the CLA. Hook later recalled: "At our very first meeting, it became clear to us that the Trotskyists could not conceive a situation in which the workers' democratic councils could overrule the Party or indeed one in which there would be plural working class parties. The meeting dissolved in intense disagreement." However, despite this poor beginning, the two groups merged in December 1934.

In 1940 Muste was appointed executive secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). In this position Muste led the campaign against United States involvement in the Second World War. In 1942 Muste encouraged James Farmer and Bayard Rustin to establish the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Early members included George Houser and Anna Murray. Members were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America.

After the war Muste joined with David Dillinger and Dorothy Day to establish the Direct Action magazine in 1945. Dellinger once again upset the political establishment when he criticised the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave George Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

The Congress of Racial Equality also organised Freedom Rides in the Deep South. In Birmingham, Alabama, one of the buses was fire-bombed and passengers were beaten by a white mob. Norman Thomas described these young people as "secular saints" I. F. Stone has argued: They and a few white sympathizers as youthful and devoted as themselves have begun a social revolution in the South with their sit-ins and their Freedom Rides. Never has a tinier minority done more for the liberation of a whole people than these few youngsters of C.O.R.E. (Congress for Racial Equality) and S.N.C.C. (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee)."

By 1961 Congress of Racial Equality had 53 chapters throughout the United States. Two years later, the organization helped organize the famous March on Washington. On 28th August, 1963, more than 200,000 people marched peacefully to the Lincoln Memorial to demand equal justice for all citizens under the law. At the end of the march Martin Luther King made his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

Abraham J. Muste was also very active in the War Resisters League and helped influence civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King and Whitney Young, to oppose the Vietnam War.

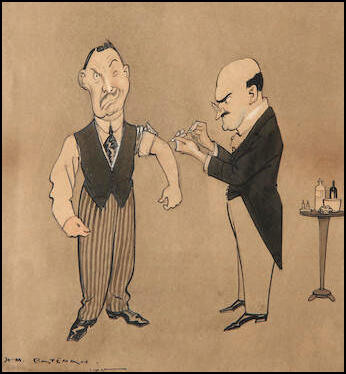

On this day in 1970 cartoonist Henry Mayo Bateman died. Bateman, the son of Henry Charles Bateman, was born to an English family in Sutton Forest, New South Wales on 15th February, 1887. His father owned an export and packing business in Australia but in 1889 the family returned to England.

Encouraged by Phil May he studied at the Westminster School of Art and the Goldsmith's Institute. On the recommendation of John Hassall he joined the studio run by Charles van Havermaet. His first cartoons appeared in The Royal Magazine and The Tatler. He began contributing to Punch Magazine in 1906.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Bateman joined the London Regiment but after falling ill with rheumatic fever in 1915 he was discharged. Over the next few years Bateman had cartoons published in Punch Magazine, The London Magazine, The Bystander, The Strand Magazine and The Humorist.

After the war Bateman became one of the highest paid cartoonist of his day and produced a considerable amount of work for advertising. This included campaigns for Wills Cigarettes, Moss Bros, Guinness, Shell and Lucky Strike. By the 1930s Bateman was recognised as one of Britain's leading cartoonists and was earning over £5,000 a year for his work. Bateman was one of the first graphic artists to adopt a cinematic approach. One critic has argued that Bateman episodic format was "closely parallelled in the silent movie, such as the slow build up to a climax or denouement, and a new emphasis on gesture and facial expression".

Bateman published several books including A Book of Drawings (1921), More Drawings (1922), Bateman (1931) The Art of Caricature (1936) and On the Move in England (1940). During the Second World War Bateman produced several posters for the government.

R.G.G. Price, the author of A History of Punch (1957) has argued that Bateman "probably did more than anyone to bring home to the reader that individual pen and ink lines could be immensely expressive of and by themselves." Mark Bryant has pointed out that Bateman "worked in pencil, pen, ink and watercolour on Canson paper... and was the "master of the cartoon story without words."

On this day in 1976 Lee J. Cobb at his home in Woodland Hills, California. Cobb was born in New York on 8th December, 1911. He studied at New York University before joining the Group Theatre in 1935 where he appeared with Elia Kazan in Waiting for Lefty, the highly successful play by Clifford Odets. He made his screen debut in The Vanishing Shadow (1934). This was followed by North of the Rio Grande (1937), Ali Baba Goes to Town (1937) and Golden Boy (1938).

Cobb became an established film star and appeared in The Song of Bernadette (1943), Winged Victory (1944), Anna and the King of Siam (1946), Johnny O'Clock (1947), Boomerang! (1947) and Captain from Castile (1947).

In 1947 Cobb played the lead role of Willy Loman in Death Of A Salesman, a play written by Arthur Miller and directed by Elia Kazan. The play opened at the Morosco Theatre on 10th February, 1949. It also featured Mildred Dunnock (Linda), Arthur Kennedy (Biff) and Cameron Mitchell (Happy).

Death Of A Salesman played for 742 performances and won the Tony Award for best play, supporting actor, author, producer and director. It also won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play. Arthur Miller was himself highly critical of the play: "I knew nothing of Brecht then or of any other theory of theatrical distancing: I simply felt that there was too much identification with Willy, too much weeping, and that the play's ironies were being dimmed out by all this empathy."

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. The HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

One of those named, Bertolt Brecht, an emigrant playwright, gave evidence and then left for East Germany. Ten others: Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz,, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie refused to answer any questions.

Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The House of Un-American Activities Committee and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of congress and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison.

Others called before the HUAC were willing to testify and Cobb was named by Larry Parks in 1951. For two years he refused to appear but in 1953 he changed his mind and named twenty people as former members of the Communist Party. He later explained why: "The HUAC did a deal with me. I was pretty much worn down. I had no money. I couldn't borrow. I had the expenses of taking care of the children. Why am I subjecting my loved ones to this? If it's worth dying for, and I am just as idealistic as the next fellow. But I decided it wasn't worth dying for, and if this gesture was the way of getting out of the penitentiary I'd do it. I had to be employable again."

Arthur Miller, who refused to give evidence against former friends recalled: "I could not help thinking of Lee Cobb, my first Willy Loman, as more a pathetic victim than a villain, a big blundering actor who simply wanted to act, had never put in for heroism, and was one of the best proofs I knew of the Committee's pointless brutality toward artists. Lee, as political as my foot, was simply one more dust speck swept up in the thirties idealization of the Soviets, which the Depression's disillusionment had brought on all over the West."

After giving evidence to the House of Un-American Activities Committee Cobb was free to return to acting in Hollywood. He worked with Elia Kazan and Budd Schulberg, two others who named names, on the Academy Award winning film, On the Waterfront (1954).

Other films made by Cobb include The Left Hand of God (1955), The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956), Twelve Angry Men (1957), The Three Faces of Eve (1957), The Brothers Karamazov (1958), Exodus (1960), How the West Was Won (1962), Coogan's Bluff (1968) and The Exorcist (1973).