On this day on 7th November

On this day in 1878 Lise Meitner, who worked on nuclear physics, was born. She studied science at the University of Vienna before moving to Berlin where she joined with Otto Hahn in researching radioactivity at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. However, she was refused permission to work in the laboratory because she was a woman.

The First World War brought changes in attitudes towards women scientists and in 1917 m was appointed as head of the Physics Department in the institute. The following year Meitner and Hahn discovered protactinium. Meitner was appointed professor at the Berlin Institute of Theoretical Physics in 1926 and carried out important investigations into the products of neutron bombardment of uranium.

Meitner, like other Jews in Germany, was dismissed from her university post in 1938. She moved to Sweden and in 1939 wrote a paper with Otto Frisch explaining the theory of uranium fission. In the paper they argued that by splitting the atom it was possible to use a few pounds of uranium to create the explosive and destructive power of many thousands of pounds of dynamite. However, unlike other scientists working in this field, Meitner refused to go the United States and work on the Manhattan Project that was attempting to produce the atomic bomb.

On this day in 1837 abolitionist printer Elijah Lovejoy is shot dead by a mob. In 1834 Lovejoy became the pastor of the Presbyterian Church in St. Louis. He started a religious newspaper, the St. Louis Observer, where he advocated the abolition of slavery. In 1836 Lovejoy published a full account of the lynching of an African American in St. Louis and the subsequent trial that acquitted the mob leaders. This critical report angered some local people and in July, 1836, his press was destroyed by a white mob.

Unable to publish his newspaper in St. Louis, Lovejoy moved to Alton, Illinois where he became an active member of the local Anti-Slavery Society. He also began editing the Alton Observer and continued to advocate the end of slavery. Three times Lovejoy's printing press was seized by white mobs thrown into the Mississippi River. Lovejoy wrote in his paper: "We distinctly avow it to be our settled purpose, never, while life lasts, to yield to this new system of attempting to destroy, by means of mob violence, the right of conscience, the freedom of opinion, and of the press."

On 7th November, 1837, Lovejoy received another press from the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society. When local slave-owners heard about the arrival of the new machine, they decided to destroy it. A group of his friends attempted to protect it, but during the attack, Lovejoy was shot dead.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was America's first martyr to freedom of the press. In 1952 the Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award was established and it is given to a member of the newspaper profession who continues the Lovejoy heritage of fearlessness and freedom.

On this day in 1880 Queen Victoria tells Prime Minister William Gladstone that she is against women’s suffrage. Gladstone's daughter, Mary Gladstone, convinced him that women should be allowed to vote. Queen Victoria was completely against any attempts at parliamentary reform and she was in constant conflict with Gladstone over government policy. She often wrote to him complaining about his progressive policies. When he became prime minister in 1880 she warned him about the appointment of advance Radicals such as Joseph Chamberlain, Charles Wentworth Dilke, Henry Fawcett, James Stuart and Anthony Mundella, The Queen was also disappointed that Gladstone had not found a place for George Goschen, in his government, a man who she knew was strongly against parliamentary reform.

In November, 1880, Queen Victoria she told him that he should be careful about making statements about future political policy: "The Queen is extremely anxious to point out to Mr. Gladstone the immense importance of the utmost caution on the part of all the Ministers but especially of himself, at the coming dinner in the City. There is such danger in every direction that a word too much might do irreparable mischief." The following year she made a similar comment: "I see you are to attend a great banquet at Leeds. Let me express a hope that you will be very cautious not to say anything which could bind you to any particular measures."

Gladstone's private secretary, Edward Walter Hamilton, claimed that he wrote to the Queen over a thousand times, and his letters were frequently in reply to hers. Victoria often complained about the speeches made by his most progressive cabinet ministers, Joseph Chamberlain and Charles Wentworth Dilke. Hamilton wrote to the Queen pointing out: "Your Majesty will readily believe that he (William Gladstone) has neither the time nor the eyesight to make himself acquainted by careful perusal with all the speeches of his colleagues".

In 1884 Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. The bill faced serious opposition in the House of Commons. The Tory MP, William Ansell Day, argued: "The men who demand it are not the working classes... It is the men who hope to use the masses who urge that the suffrage should be conferred upon a numerous and ignorant class."

George Goschen had been one of the leading Liberal opponents to the 1867 Reform Act. However, he supported the 1884 Reform Act: "The argument against the enfranchisement of the working class was this - and no doubt it is a very strong argument - the power they would have in any election if they combined together on questions of class interest. We are bound not to put that risk out of sight. Well, at the last election, I carefully watched the various contests that were taking place and I am bound to admit that I saw no tendency on the part of the working classes to combine on any special question where their pecuniary interests were concerned. On the contrary, they seemed to me to take a genuine political interest in public questions ... The working classes have given proofs that they are deeply desirous to do what is right."

The bill was passed by the Commons on 26th June, with the opposition did not divide the House. The Conservatives were hesitant about recording themselves in direct hostility to franchise enlargement. However, Gladstone knew he would have more trouble with the House of Lords. Gladstone wrote to twelve of the leading bishops and asked for their support in passing this legislation. Ten of the twelve agreed to do this. However, when the vote was taken the Lords rejected the bill by 205 votes to 146.

Queen Victoria thought that the Lords had every right to reject the bill and she told Gladstone that they represented "the true feeling of the country" better than the House of Commons. Gladstone told his private secretary, Edward Walter Hamilton, that if the Queen had her way she would abolish the Commons. Over the next two months the Queen wrote sixteen letters to Gladstone complaining about speeches made by left-wing Liberal MPs.

On this day in 1899 Jacob Bright died. In November 1867, Bright, who was a Quaker, was elected to represent Manchester in the House of Commons. Bright now joined forces with John Stuart Mill, another supporter of women's suffrage. In a debate on the 1867 Reform Act, Mill proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

Mill lost his Commons seat in 1868, and Bright became leader of the suffragists in parliament, and took charge of the Women's Disabilities Removals Bill. In 1870 Bright and Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke introduced what was the first women's suffrage bill. In one speech he argued: "I know of no reason for the electoral disabilities of women. I know some reasons, which if there are to be electoral disabilities, would lead me to begin elsewhere than with women. Women are less criminal than men: they are more temperate than men the distinction is not small, it is broad and conspicuous; women are less vicious in their habits than men; they are more thrifty, more provident: they give more to the family, and take less to themselves."

After its defeat he introduced another Women's Suffrage Bill in 1871. Once again, William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, arranged for it to be defeated and commented that women voting in elections would be "a practical evil of an intolerable character".

Jacob Bright made several attempts to introduce the Married Property Act. These ended in failure and he lost his seat in February 1874. Lydia Becker carried out negotiations with other members of the House of Commons. She was prepared to accept a new clause excluding all married women from the vote. This upset a large number of campaigners.

Bright returned in February 1876 and introduced his last bill in the Commons on women's suffrage in 1878. During the subsequent debates within the women's suffrage movement, he held out for the full franchise demand, including married women, rather than the more limited enfranchisement of widows and single women, that had been advocated by Becker and the more conservative members of the movement.

His wife, Ursula Bright, continued the fight over women's rights and was a member of the executive committee of the Married Women's Property Committee for fourteen years. The passing of the 1882 Married Women's Property Act was acknowledged to have been due to her efforts. Elizabeth Cady Stanton noted "for ten consecutive years she gave her special attention to this bill… was unwearied in her efforts, in rolling up petitions, scattering tracts, holding meetings".

Jacob Bright was accused of being obsessed with the subject of women's suffrage. The Englishwoman's Review commented: "Jacob Bright was not only one of the earliest parliamentary leaders of the women's suffrage movement but throughout the whole of his political career one of its most constant and more courageous champions".

On this day in 1900 Nellie Campobello was born. In 1923, after the Mexican Revolution, she moved to Mexico City. In 1931, she published her most well-known novel, Cartucho. Campobello described her motivation to write the novel as one of "avenging an injury". After the end of the armed movement, some revolutionaries were tried against the group in power, including Francisco Villa. It has been argued that it is a feminist version of the Revolution.

On this day in 1909 Ruby Hurley, American civil rights activist was born. In 1939 she ran the Washington D. C. branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Walter Francis White, who headed the NAACP, appointed Hurley to the position of national Youth Secretary in 1943. She moved to New York City and stayed in that role until 1950. Hurley traveled across the country organizing youth councils and college chapters, increasing their number from 86 to over 280 during her tenure.

In 1951, she moved from New York to Birmingham, Alabama, to set up an NAACP office and oversee membership drives in Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. It was the first permanent NAACP office located in the Deep South. In 1955, Hurley joined with Medgar Evers, who was Field Secretary at the NAACP's Mississippi office, in investigating the murders of Herbert Lee and 14-year-old Emmett Till. Hurley was forced to flee Alabama in the night on June 1, 1956, after the state barred the NAACP from operating there.

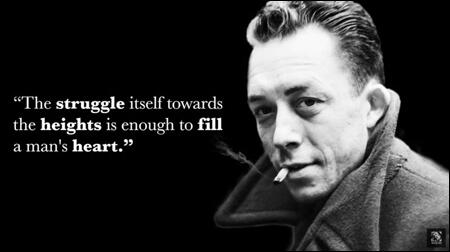

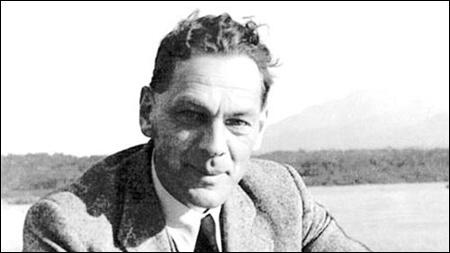

On this day in 1913 Albert Camus, the son of a farm labourer, was born in Mondovi, Algeria. On the outbreak of the First World War his father joined the French Army. Soon afterwards he was killed at the Marne. Camus won a scholarship to Algiers High School. A good student, he was also a talented sportsman until he developed tuberculosis in 1930.

Camus studied philosophy at Algiers and after graduation worked as a schoolmaster, playwright and journalist. His first collection of essays, The Wrong Side of the Right Side, was published in 1937. This was followed by another collection about Algeria called Nuptials (1938).

Camus moved to Paris during the Second World War and wrote for Paris-Sour (March to December, 1940). By now Camus held socialist views and after Henri-Philippe Petain signed the armistice with Germany he joined the French Resistance. Later Camus became co-editor with Jean Paul Sartre of the clandestine newspaper, Combat.

He gained international fame with his existentialist novel The Stranger (1942). This followed by The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), a philosophical look at suicide. After the war his literary reputation grew with The Plague (1948), The Rebel (1954) and The Fall (1957). Camus was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. He declared that he did not deserve the award and claimed it should have gone to André Malraux instead.

Albert Camus was killed in a car accident at Petit-Villeblev in 1960. An unfinished autobiographical novel, The First Man, was published after his death

On this day in 1916 Jeannette Rankin is the first woman elected to the United States Congress. While a student in Washington she became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage and eventually became legislative secretary of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

A member of the Republican Party, in 1916 Rankin decided to run for Congress. Rankin, who campaigned for universal suffrage, prohibition, child welfare reform, an end to child labour and staying out of the First World War, became the first woman to be elected to the House of Representatives. One of her first actions was to introduce a bill that would have allowed women citizenship independent of their husbands.

A pacifist, Rankin was one of the 49 members of Congress to vote against war with Germany. Fellow suffragists such as Carrie Chapman Catt urged Rankin to change her mind, fearing that she would damage the cause by reflecting the view that women were sentimental and irresponsible.

Rankin's controversial views on the First World War, trade union rights, equal pay and birth-control, lost her the Republican Senate nomination in 1918. She therefore stood as an independent but without the support of a party machine, was easily defeated.

On this day in 1918 Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party (ISP) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. The following month Eisner formed a coalition government with the Social Democratic Party. During this period the living conditions of the Munich workers and soldiers were rapidly deteriorating. It was not a surprise when at the election on 12th January, 1919, in Bavaria, Eisner and the ISP received only 2.5 per cent of the total vote.

Eisner remained in power by granting concessions to the SDP. This included agreeing to the establishment of a regular security force to maintain order. As Chris Harman pointed out: "In office without any power base of his own, he was forced to behave in an increasingly arbitrary and apparently irrational manner". On 21st February, 1919, Eisner decided to resign. On his way to parliament he was assassinated by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land."

On this day in 1919 Herschel Grynszpan assassinated Ernst vom Rath, a minor official at the German Embassy in Paris. Grynszpan was born in Honover, Germany in 1919. As German Jews the family suffered persecution after Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933.

In 1936 Grynszpan moved to France to live with with his uncle and aunt living in Paris. On 7th November, 1938, Grynszpan decided to assassinate the German Ambassador in France. It appears that this was an act of revenge for the expulsion of around 15,000 Polish Jews, including his own family, who in October 1938, had been forced across the Silesian border at Zbaszyn.

However, after waiting outside for some time for the German Ambassador he shot Ernst vom Rath, a minor official at the embassy. He died two days later. Rath was in fact an anti-Nazi and was under investigation by the Gestapo at the time. As a result of the assassination the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) organized Crystal Night on the night of 9th-10th November, 1938. During Crystal Night over 7,500 Jewish shops were destroyed and 400 synagogues were burnt down. Ninety-one Jews were killed and an estimated 20,000 were sent to concentration camps.

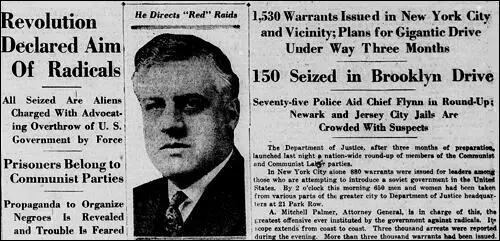

On this day in 1919 Alexander Palmer, US Attorney General, ordered the arrest of 10,000 left-wing political activists. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. His view was reinforced by the discovery of thirty-eight bombs sent to leading politicians and the Italian anarchist who blew himself up outside Palmer's Washington home. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman and 247 other people, were deported to Russia.

In January, 1920, another 6,000 were arrested and held without trial. These raids took place in several cities and became known as the Palmer Raids. Although they found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects, many of them members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), continued to be held without trial. When Palmer announced that the communist revolution was likely to take place on 1st May, mass panic took place. In New York, five elected Socialists were expelled from the legislature.

When the May revolution failed to materialize, attitudes towards Palmer began to change and he was criticised for disregarding people's basic civil liberties. Some of his opponents claimed that Palmer had devised this Red Scare to help him become the Democratic presidential candidate in 1920.

On this day in 1921 Susanne Hirzel, member of the White Rose was born. After the election of Adolf Hitler she joined the German League of Girls (BDM). Her group leader was Sophie Scholl. Hirzel later recalled: "I got to know Sophie Scholl when she was my group leader in the BDM. I admired her because of her eloquence and her behavior and she quickly became my very best friend. I often stayed at Sophie's parents' home and got to know her brother Hans and her sister Inge. The BDM was a scouting organization for girls. Political indoctrination was only one aspect among many others and I even became a troop leader (Scharführerin)."

Sophie's father, Robert Scholl, was a strong opponent of the Nazi Party. Sophie's sister, Elisabeth Scholl later pointed out why they rejected their father's advice: "We just dismissed it: he's too old for this stuff, he doesn't understand. My father had a pacifist conviction and he championed that. That certainly played a role in our education.

Susanne Hirzel was a regular visitor to the Scholl family home. Hans Scholl was a local leader of the Hitler Youth and was chosen to be the flag bearer when his unit attended the Nuremberg Rally in 1936. His sister, Inge Scholl, later recalled: "His joy was great. But when he returned, we could not believe our eyes. He looked tired and showed signs of a great disappointment. We did not expect any explanation from him, but gradually we found out that the image and model of the Hitler Youth which had been impressed upon him there was totally different from his own ideal... Hans underwent a remarkable change... This had nothing to do with Father's objections; he was able to close his ears to those. It was something else. The leaders had told him that his songs were not allowed... Why should he be forbidden to sing these songs that were so full of beauty? Merely because they had been created by other races?"

Sophie Scholl was very close to Hans and she also became disillusioned with Adolf Hitler. Shortly after Hans returned from Nuremberg, an important BDM leader arrived from Stuttgart to conduct an evening of ideological training for the girls in Ulm. When the members were asked if they had any preferences for discussion, Sophie suggested they read poems by Heinrich Heine, one of her favourite writers. The leader was appalled and pointed out that the left-wing, anti-war, Jewish writer, had his books burned and banned by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in 1933. Apparently, Sophie replied, "Whoever doesn't know Heine, does not know German literature."

Susanne Hirzel also became more critical of the Nazi government. She later claimed that Robert Scholl was an important factor in this. Scholl held liberal opinions and allowed his children to make their own choices. According to Richard F. Hanser: "They could say whatever they wished, and they all had opinions. This was far from customary practice in German households, where, by long tradition, the authority of the father was seldom questioned or his statements challenged... His aversion to mindless nationalism was not only unchanged but stronger than before. In his dinner-table discussions with his children, he could interpret events for them with an insight unblurred by current prejudices or official pronouncements." Hirzel later recalled: "Sophie's father Robert Scholl was a determined Catholic pacifist and a sincere Christian. He told us about his experiences and that influenced my thinking."

In 1942 a group of students at the University of Munich established the White Rose group. It included Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, and Jugen Wittenstein. According to Elisabeth Scholl, the White Rose group was formed because of the execution of members of the resistance: "We learned in the spring of 1942 of the arrest and execution of 10 or 12 Communists. And my brother said, In the name of civic and Christian courage something must be done.” Susanne Hirzel also joined the group.

In June 1942 the White Rose group began producing leaflets. They were typed single-spaced on both sides of a sheet of paper, duplicated, folded into envelopes with neatly typed names and addresses, and mailed as printed matter to people all over Munich. At least a couple of hundred were handed into the Gestapo. It soon became clear that most of the leaflets were received by academics, civil servants, restaurateurs and publicans. A small number were scattered around the University of Munich campus. As a result the authorities immediately suspected that students had produced the leaflets.

The opening paragraph of the first leaflet said: "Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be "governed" without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes - crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure-reach the light of day? If the German people are already so corrupted and spiritually crushed that they do not raise a hand, frivolously trusting in a questionable faith in lawful order in history; if they surrender man's highest principle, that which raises him above all other God's creatures, his free will; if they abandon the will to take decisive action and turn the wheel of history and thus subject it to their own rational decision; if they are so devoid of all individuality, have already gone so far along the road toward turning into a spiritless and cowardly mass - then, yes, they deserve their downfall."

In January, 1943, the White Rose group produced a leaflet, entitled A Call to All Germans!, included the following passage: "Germans! Do you and your children want to suffer the same fate that befell the Jews? Do you want to be judged by the same standards as your traducers? Are we do be forever the nation which is hated and rejected by all mankind? No. Dissociate yourselves from National Socialist gangsterism. Prove by your deeds that you think otherwise. A new war of liberation is about to begin."

It ended with the kind of world they wanted after the war finished: "Imperialistic designs for power, regardless from which side they come, must be neutralized for all time... All centralized power, like that exercised by the Prussian state in Germany and in Europe, must be eliminated... The coming Germany must be federalistic. The working class must be liberated from its degraded conditions of slavery by a reasonable form of socialism... Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the protection of individual citizens from the arbitrary will of criminal regimes of violence - these will be the bases of the New Europe."

On 18th February, 1943, Sophie and Hans Scholl arrived at the University of Munich with a suitcase packed with leaflets. According to Inge Scholl: "They arrived at the university, and since the lecture rooms were to open in a few minutes, they quickly decided to deposit the leaflets in the corridors. Then they disposed of the remainder by letting the sheets fall from the top level of the staircase down into the entrance hall. Relieved, they were about to go, but a pair of eyes had spotted them. It was as if these eyes (they belonged to the building superintendent) had been detached from the being of their owner and turned into automatic spyglasses of the dictatorship. The doors of the building were immediately locked, and the fate of brother and sister was sealed."

Jakob Schmid, a member of the Nazi Party, saw them at the University of Munich, throwing leaflets from a window of the third floor into the courtyard below. He immediately told the Gestapo and they were both arrested. They were searched and the police found a handwritten draft of another leaflet. This they matched to a letter in Scholl's flat that had been signed by Christoph Probst. Following interrogation, they were all charged with treason.

Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst were all tried for high treason on 22nd February, 1943. They were all found guilty. Judge Roland Freisler told the court: "The accused have by means of leaflets in a time of war called for the sabotage of the war effort and armaments and for the overthrow of the National Socialist way of life of our people, have propagated defeatist ideas, and have most vulgarly defamed the Führer, thereby giving aid to the enemy of the Reich and weakening the armed security of the nation. On this account they are to be punished by death. Their honour and rights as citizens are forfeited for all time." They were all executed later that day.

Susanne Hirzel was arrested and put on trial on 19th April, 1943. She later claimed that she expected to be executed. She told the court that her brother Hans Hirzel, had asked her to post the leaflets. As they were in the envelopes she claimed that she did not know the content of the leaflets. Judge Freisler said she gave the impression of candor and did not know her brother was engaged in treasonous activity. She was sentenced six months in prison. Her brother got five years. Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber and Willi Graf were all found guilty of high treason and executed.

On this day in 1944 Richard Sorge, Soviet spy, is hanged by his Japanese captors. Sorge was a member of a group of Soviet agents that became known as the "Great Illegals" who agreed with Leon Trotsky on the subject of world revolution. This is why they were willing to work undercover in the countries hostile to the Soviet Union in an effort to ferment revolution. This group included Arnold Deutsch, Walter Krivitsky, Theodore Maly, Ignace Reiss, Leopard Trepper, Alexander Orlov, Artur Artuzov, Yan Berzin, Boris Vinogradov, Peter Gutzeit, Boris Bazarov, Dmitri Bystrolyotov and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko. By the summer of 1937, Stalin became convinced that these agents were conspiring against him and over forty of them serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union. Deutsch, Maly, Berzin, Artuzov, Vinogradov, Gutzeit, Bazarov and Antonov-Ovseenko were all executed. Reiss and Krivitsky refused to return and were murdered abroad.

Sorge, a journalist, was successful at appearing to be a passionate supporter of the Nazi Party. This helped him develop good relations with several important figures working at the German Embassy in Tokyo. This included Eugen Ott and the German Ambassador Herbert von Dirksen. This enabled him to find out information about Germany's intentions towards the Soviet Union. Other spies in the network had access to senior politicians in Japan including prime minister Fumimaro Konoye and they were able to obtain secret details of Japan's foreign policy.

Sorge always maintained that his job as a writer for newspapers and magazines helped him enormously in his quest for intelligence. "A shrewd spy will not spend all his time on the collection of military and political secrets and classified documents. Also, I may add, reliable information cannot be procured by effort alone; espionage work entails the accumulation of information, often fragmentary, covering a broad field, and the drawing of conclusions based thereon. This means that a spy in Japan, for example, must study Japanese history and the racial characteristics of the people and orient himself thoroughly on Japan's politics, society, economics and culture." (30) Such was his success Sorge has been described as "among the greatest spies of the century."

The Japanese became convinced there was a spy inside the German Embassy. They also discovered that an illegal radio transmitter was being used by the Russians in Tokyo. In October, 1941, the Japanese police arrested Yotoku Miyagi, one of the key figures in Sorge's network. He attempted suicide by leaping head-first from an upper-storey window of the police station, but shrubbery broke his fall. Under torture he confessed, and gave the name of Sorge and his associates.

Sorge was eventually arrested. Ambassador Eugen Ott was outraged when he heard the news and thought it was a "typical case of Japanese espionage hysteria". He told people around him "Sorge a spy? What twaddle! I would put my hand in the fire for the man." Heinrich Loy, a German working in Tokyo, also found it difficult to believe: "I've known Sorge personally for a long time, but this news surprised me and made me realise he was different from other people. Normally people you've known a long time will make a careless slip on some occasion. Particularly when someone drinks like a fish, as Sorge did, you expect that he will reveal his true self. Considering that he managed to conceal his identity up until now, I have to say he was an exceptional man."

Richard Sorge was executed by the Japanese on 7th November 1944 his last words were: “The Red Army!”, “The International Communist Party!” and “The Soviet Communist Party!”, all delivered in fluent Japanese to his captors. According to William Boyd "Sorge was bound hand and foot, the noose already set around his neck. Tall, blue-eyed, ruggedly good-looking and apparently unperturbed by his imminent demise, Sorge was contributing the perfect denouement to what he might well have assumed was an enduring myth in the making."

On this day in 1961 Mary Raleigh Richardson died of heart failure and bronchitis, aged seventy-eight, at her home in Hastings.

Mary Raleigh Richardson was born in England in 1882 but was brought up by her Canadian mother in Belleville, Ontario. She returned to Britain when she was sixteen, studying art and travelling to France and Italy. While living in Bloomsbury she became a journalist.

On 18th November, 1910 the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) lobbied Parliament. She witnessed the way the police brutally attacked the women. She immediately joined the WSPU and quickly engaged in militant activities. She later described this as "a holy crusade".

Over the next few years she was arrested nine times, serving several sentences in Holloway Prison for assaulting the police and breaking windows. She has been described "as one of the most militant suffragettes, who was arrested nine times and was one of the first two suffragettes to be forcibly fed".

On one occasion Mary Richardson was asked by the prison doctor whether she would refrain from militancy on her release, she answered: "I shall be militant as long as I can stand or see; they cannot do more than kill me." He replied: "It is not a question of killing you... you will be kept till you are a skeleton, and a nervous and mental wreck, and then you will be sent to an institution where they look after mental wrecks."

Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. It is believed that Richardson was responsible for setting fire to The Elms, a house owned by Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle.

Mary Richardson later recalled the first time she set fire to a building: "I took the things from her and went on to the mansion. The putty of one of the ground-floor windows was old and broke away easily, and I had soon knocked out a large pane of the glass. When I climbed inside into the blackness it was a horrible moment. The place was frighteningly strange and pitch dark, smelling of damp and decay... A ghastly fear took possession of me; and, when my face wiped against a cobweb, I was momentarily stiff with fright. But I knew how to lay a fire - I had built many a camp fire in my young days -a nd that part of the work was simple and quickly done. I poured the inflammable liquid over everything; then I made a long fuse of twisted cotton wool, soaking that too as I unwound it and slowly made my way back to the window at which I had entered."

In June, 1913, Richardson attended the most important race of the year, the Derby, with Emily Davison: "A minute before the race started she raised a paper on her own or some kind of card before her eyes. I was watching her hand. It did not shake. Even when I heard the pounding of the horses' hoofs moving closer I saw she was still smiling. And suddenly she slipped under the rail and ran out into the middle of the racecourse. It was all over so quickly." Davison ran out on the course and attempted to grab the bridle of Anmer, a horse owned by King George V. The horse hit Emily and the impact fractured her skull and she died on 8th June without regaining consciousness. Richardson escaped to "Epsom Station where a sympathetic station master hid her in the ladies' loo until the hue and cry were over".

On 18th July, 1913, Mary Richardson was sentenced to a month's hard labour for throwing an inkpot through a window of a police station. She went on hunger strike and was released five days later as a result of the Cat & Mouse Act. As soon as she recovered she was arrested again. Every time she was released she carried out another act of violence.

In 1913 the WSPU arson campaign escalated and railway stations, cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire. Slogans in favour of women's suffrage were cut and burned into the turf. Suffragettes also cut telephone wires and destroyed letters by pouring chemicals into post boxes. The women responsible were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Richardson was arrested at the scene of an arson attack. She suffered extensive bruising and poor health as a result of being forced-fed. After being released in 1914 she was operated on for appendicitis.

On 10 March 1914 she attacked a painting, Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery. She later described what happened: "I dashed up to the painting. My first blow with the axe merely broke the protective glass. But, Of course, it did more than that, for the detective rose with his newspaper still in his hand and walked round the red plush seat, staring up at the skylight which was being repaired. The sound of the glass breaking also attracted the attention of the attendant at the door who, in his frantic efforts to reach me, slipped on the highly polished floor and fell face downward. And so I was given time to get in a further four blows with my axe before I was, in turn, attacked."

The Manchester Guardian reported the following day: "At the National Gallery, yesterday morning, the famous Rokeby Venus, the Velasquez picture which eight years ago was bought for the nation by public subscription for £45,000, was seriously damaged by a militant suffragist connected with the Women's Social and Political Union... The woman, producing a meat chopper from her muff or cloak, smashed the glass of the picture, and rained blows upon the back of the Venus. A police officer was at the door of the room, and a gallery attendant also heard the smashing of the glass. They rushed towards the woman, but before they could seize her she had made seven cuts in the canvas." Later she revealed that she hated the way nude paintings were "gloated over by men".

Richardson claimed that this act was perpetrated to draw attention to the plight of Emmeline Pankhurst, then on hunger strike in Holloway Prison, saying, "I should like to point out that the outrage which the Government has committed upon Mrs. Pankhurst is an ultimatum of outrages. It is murder, slow murder, and premeditated murder... You can get another picture but you cannot get a life, as they are killing Mrs Pankhurst". She was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months with hard labour. It also led to many museums' closing their doors to unaccompanied women.

While in prison she wrote about the condition of prisoners such as Grace Roe, Hilda Burkitt and Florence Tunks. "I was in the next cell to Grace Roe since her conviction and had frequent conversations with her. I consider her the most injured by forcible feeding of any in Holloway… Grace suffers extremely from pain in her nose, throat and stomach all day and night, says she feels as if the tube were always in her body. She says that mentally this is telling on her, and she sometimes feels something would crack in her brain. She anticipates an utter collapse on her release. She is very thin, so thin she can be in no position without positive pain in her bones; she is frightfully anaemic and says her gums are chalk white, and indeed her whole face is… In wing C, within calling distance is Hilda Burkitt who is very weak now. She has lost a stone. She is sick with each feeding. She has been fed four times a day for over a fortnight at nine, twelve, four, and eight o'clock. Next to her is Florence Tunks. She has lost twenty-seven and a half-pounds, has had two teeth broken, is generally exhausted, and cannot stand without giddiness for more than a few minutes.

On her release from prison Richardson resumed her literary career, publishing a novel, Matilda and Marcus (1915), and two volumes of poetry, Symbol Songs (1916) and Wilderness Love Songs (1917). Her third book of poetry, Cornish Headlands, appeared in 1920.

In the 1922 General Election when she stood as Labour Party candidate in Acton, obtaining 26.2 per cent of the vote. In the 1924 General Election she stood for the same seat as an independent socialist against the official Labour candidate and received 7.6 per cent of the vote. In 1931 General Election she was adopted as a last-minute Labour candidate in Aldershot but lost heavily.

In January 1932 Oswald Mosley met Benito Mussolini in Italy. Mosley was impressed by Mussolini's achievements and when he returned to England he established the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Mary Richardson was one of the first people to join: "I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service, and the ability to serve which I had known in the suffragette movement". She also liked "its policy of Imperialism, and action combined with discipline which raise the movement above comparison with the present party system."

Other former suffragettes who joined included Norah Dacre Fox, Mary Allen and Mercedes Barrington. It has been argued by Julie V. Gottlieb, the author of Feminine Fascism: Women in Britain's Fascist Movement (2003) that some militant suffragettes "settled into the seemingly inhospitable territory of British fascism during the 1930s" because of "their disillusionment with the post-war condition of the women's movement in the aftermath of female enfranchisement".

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, a former leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), expressed regret that some of its former members were active in the BUF but admitted that both organizations "bore a certain resemblance to the dictatorship so common in the world today... it is so-called upholders of democracy who create, when they are false in their principles, and when they attempt to crush their opponents, dictatorships".

In April 1934 Richardson replaced Lady Esther Makgill as head of the Women's Section. "Although the organisation obviously included many anti-feminist men, it seems clear that the female members of the BUF played a very active role... The women, who appeared prominently at fascist functions, have been estimated to comprise a quarter of the total membership. They wore a black blouse, black beret and grey skirt."

In 1953 Mary Richardson published her autobiography, Laugh a Defiance. Although she wrote in detail about her experiences in the Women's Social and Political Union she failed to mention her membership of the British Union of Fascists.

On this day in 1962 Eleanor Roosevelt, political activist died. In 1905 she married her cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Like her husband, Eleanor was a Democrat and took a strong interest in politics. However, she was far more left-wing than her husband. Eleanor worked for the League of Women's Voters, the National Consumer's League and the Women's Trade Union League. She also became friendly with the African American educator, Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White, the national secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). These friendships resulted in Eleanor taking a close interest in African American civil rights.

In 1935 Eleanor attempted to persuade Franklin D. Roosevelt to support and Anti-Lynching bill that had been introduced into Congress. However, Roosevelt refused to speak out in favour of the bill that would punish sheriffs who failed to protect their prisoners from lynch mobs. He argued that the white voters in the South would never forgive him if he supported the bill and he would therefore lose the next election.