The Struggle for Parliamentary Reform (1215-1928)

In January 1215 King John met his opponents at London - they came armed - and it was agreed that there should be another meeting in the near future. On 15th June, 1215, at Runnymede, the King was forced to accept the peace terms of his opponents. As one historian pointed out: "The leaders of the barons in 1215 groped in the dim light towards a fundamental principle. Government must henceforward mean something more than the arbitrary rule of any man, and custom and the law must stand even above the King." (1)

The document the king was obliged to sign was the Magna Carta. In this charter the king made a long list of promises, including: (XII) No scutage or aid (tax) shall be imposed on our kingdom, unless by common counsel of our kingdom. (XIV) And for obtaining the common counsel of the kingdom before the assessing of an aid or of a scutage, we will cause to be summoned the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and greater barons." (2)

This established what became known as the House of Lords. The power of Parliament depended on the strength of the monarchy and the demands they made on the people. King Edward III had problems fighting what became known as the Hundred Years War. Fighting the war was very expensive and in February 1377 the government introduced a poll-tax where four pence was to be taken from every man and woman over the age of fourteen. "This was a huge shock: taxation had never before been universal, and four pence was the equivalent of three days' labour to simple farmhands at the rates set in the Statute of Labourers". (3)

King Edward died soon afterwards. His ten-year-old grandson, Richard II, was crowned in July 1377. John of Gaunt, Richard's uncle, took over much of the responsibility of government. He was closely associated with the new poll-tax and this made him very unpopular with the people. They were very angry as they considered the tax unfair as the poor had to pay the same tax as the wealthy. (4)

Demands for Democracy

John Ball emerged as the main opponent of the Poll Tax. Ball preached that "things would not go well with England until everything was held in common". At these meetings he argued: "Are we not all descended from the same parents, Adam and Eve? So what can they show us, what reasons give, why they should be more the masters than ourselves?" It is in Ball's words that we find the early concept of the equality of all men and women, "as opposed to the rigid class divisions, privileges and injustice of feudalism; equality as justified by scripture and expressed as fraternity, that was to continue as a basic ideal of the English radical tradition." (5)

The next crisis emerged during the English Civil War. In 1646 John Lilburne, John Wildman, Richard Overton and William Walwyn formed a new political party called the Levellers. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%.

On 28th October, 1647, members of the New Model Army began to discuss their grievances at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, but moved to the nearby lodgings of Thomas Grosvenor, Quartermaster General of Foot, the following day. This became known as the Putney Debates. The speeches were taken down in shorthand and written up later. As one historian has pointed out: "They are perhaps the nearest we shall ever get to oral history of the seventeenth century and have that spontaneous quality of men speaking their minds about the things they hold dear, not for effect or for posterity, but to achieve immediate ends." (6)

Thomas Rainsborough, the most radical of the officers, argued: "I desire that those that had engaged in it should speak, for really I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he; and therefore truly. Sir, I think it's clear that every man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that Government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that Government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under; and I am confident that when I have heard the reasons against it, something will be said to answer those reasons, in so much that I should doubt whether he was an Englishman or no that should doubt of these things." (7)

John Wildman supported Rainsborough and dated people's problems to the Norman Conquest: "Our case is to be considered thus, that we have been under slavery. That's acknowledged by all. Our very laws were made by our Conquerors... We are now engaged for our freedom. That's the end of Parliament, to legislate according to the just ends of government, not simply to maintain what is already established. Every person in England hath as clear a right to elect his Representative as the greatest person in England. I conceive that's the undeniable maxim of government: that all government is in the free consent of the people." (8)

Edward Sexby was another who supported the idea of increasing the franchise: "We have engaged in this kingdom and ventured our lives, and it was all for this: to recover our birthrights and privileges as Englishmen - and by the arguments urged there is none. There are many thousands of us soldiers that have ventured our lives; we have had little property in this kingdom as to our estates, yet we had a birthright. But it seems now except a man hath a fixed estate in this kingdom, he hath no right in this kingdom. I wonder we were so much deceived. If we had not a right to the kingdom, we were mere mercenary soldiers. There are many in my condition, that have as good a condition, it may be little estate they have at present, and yet they have as much a right as those two (Cromwell and Ireton) who are their lawgivers, as any in this place. I shall tell you in a word my resolution. I am resolved to give my birthright to none. Whatsoever may come in the way, and be thought, I will give it to none. I think the poor and meaner of this kingdom (I speak as in that relation in which we are) have been the means of the preservation of this kingdom." (9)

These ideas were opposed by most of the senior officers in the New Model Army, who represented the interests of property owners. One of them, Henry Ireton, argued: "I think that no person hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the kingdom, and indetermining or choosing those that determine what laws we shall be ruled by here - no person hath a right to this, that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom... First, the thing itself (universal suffrage) were dangerous if it were settled to destroy property. But I say that the principle that leads to this is destructive to property; for by the same reason that you will alter this Constitution merely that there's a greater Constitution by nature - by the same reason, by the law of nature, there is a greater liberty to the use of other men's goods which that property bars you." (10)

A compromise was eventually agreed that the vote would be granted to all men except alms-takers and servants and the Putney Debates came to an end on 8th November, 1647. The agreement was never put before the House of Commons. Leaders of the Leveller movement, including John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and John Wildman, were arrested and their pamphlets were burnt in public. (11)

Glorious Revolution

John Locke took up the ideas of the Levellers in his Two Treatises of Government. Written in about 1680 but not published until ten years later, it disputed the idea that the monarch's political authority was derived from God (the concept known as Divine Right) because it could lead to absolute monarchy which, he asserted, was "inconsistent with civil society, and so can be no form of civil government at all." (12)

According to Annette Mayer, in her book, The Growth of Democracy in Britain (1999): "In Locke's view, sovereignty resided in the people and government depended upon their direct consent. A government's role was to protect the rights and liberties of the people, but if the governors failed to rule according to the laws then they would forfeit the people's trust. The people possessed the right to choose an alternative government." (13)

Just before he died in February 1685, Charles II admitted that he was a Catholic. He also announced that his brother James was to succeed him to the throne. In June 1685, the Duke of Monmouth landed in England with a small army. As he was a Protestant he expected most of the population to support his claim to the throne, but people in England were unwilling to get involved in another Civil War. Monmouth was therefore easily defeated by the king's army. (14)

After this victory James II tried to place Catholic friends in positions of power. However, the Test Acts made it impossible for him to do this. When Parliament refused to change these laws, he ignored it and began appointing Catholics to senior positions in the army and the government. James also announced that he intended to allow Catholics to have complete religious freedom in England. When the Archbishop of Canterbury and six other bishops objected to this, James gave instructions for them to be arrested and sent to the Tower of London. (15)

Some members of the House of Commons sent messages to Holland inviting James's daughter, Mary and her husband, William, Prince of Orange to come to England. Mary and William were told that, as they were Protestants, they would have the support of Parliament if they attempted to overthrow James.

In November 1688, William, Prince of Orange and his Dutch army arrived in England. When the English army refused to accept the orders of their Catholic officers, James fled to France. As the overthrow of James had taken place without a violent Civil War, this event became known as the Glorious Revolution. (16)

William and Mary were now appointed by Parliament as joint sovereigns. However, Parliament was determined that it would not have another monarch that ruled without its consent. The king and queen had to promise they would always obey laws made by Parliament. They also agreed that they would never raise money without Parliament's permission. So that they could not get their own way by the use of force, William and Mary were not allowed to keep control of their own army. In 1689 this agreement was confirmed by the passing of the Bill of Rights. (17)

Parliament in the 18th Century

By the 18th century it is estimated that in England and Wales about one in eight men could vote, the figure being lower in Scotland and Ireland. The right to vote depended very much on one's locality because there was no uniform franchise. In the counties, all freeholders (those people whose property had a rateable value of more than 40 shillings a year, possessed the franchise. In the boroughs, a number of qualifying systems prevailed. One factor did remain constant - the voter had to possess property. (18)

The ratio of MPs to population fluctuated wildly. A rotten borough was a parliamentary constituency that had declined in size but still had the right to elect members of the House of Commons. Plympton Earle had been a prosperous market town in the Middle Ages but by the 18th century it had declined to the level of a country village. Newtown on the Isle of Wight had been a market town but was now reduced to a village of 14 houses.

Most of these constituencies were under the control of one man, the patron. Rotten boroughs had very few voters. For example, Dunwich in Suffolk, as a result of coastal erosion, had almost fallen into the sea. "The town of Old Sarum, which contains not three houses, sends two members; and the town of Manchester, which contains upwards of sixty thousand souls, is not admitted to send any. Is there any principle in these things?" (19)

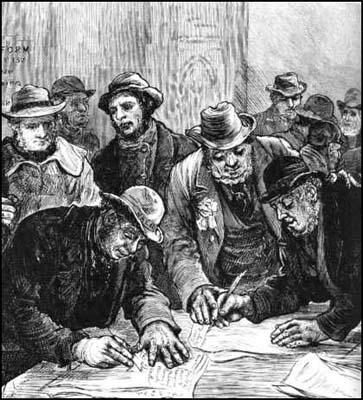

With just a few individuals with the vote and no secret ballot, it was easy for candidates to buy their way to victory. For example, William Wilberforce, decided to pursue a political career and at the age of twenty, he decided to become a candidate in the forthcoming parliamentary election in Kingston upon Hull in September 1780. His opponent was a rich and powerful member of the nobility, and Wilberforce had to spend nearly £9,000 on the 1,500 voters to become elected. (20)

A pocket borough was a parliamentary constituency owned by one man who was known as the patron. Since the patron controlled the voting rights, he could nominate the two members who were to represent the borough. Some big landowners owned several pocket boroughs. For example, at the beginning of the 18th century, the Duke of Devonshire and Lord Darlington both had the power to nominate seven members of the House of Commons. Others, like Lord Fitzwilliam and Lord Lonsdale had even more seats under their control. All these men also had seats in the House of Lords. (21)

Sir Philip Francis the MP for Appleby wrote to his wife describing how "yesterday morning, between 11 and 12, I was unanimously elected by one elector to represent the ancient borough of Appleby... there was no other candidate, no opposition, no poll demanded." He added that "on Friday morning I shall quit this triumphant scene with flying colours and a noble determination not to see it again in less than seven years." (22)

There were just a couple of constituencies that were not under the control of any one person. This was true of the Middlesex constituency. John Wilkes, the owner of the newspaper, The North Briton, was an outspoken opponent of the monarchy and a supporter of freedom of speech. On 23rd April 1763, George III and his ministers decided to prosecute Wilkes for seditious libel. He fled to France but returned to stand in the 1768 election. (23)

After being elected Wilkes was arrested and taken to King's Bench Prison. For the next two weeks a large crowd assembled at St. George's Field, a large open space by the prison. On 10th May, 1768 a crowd of around 15,000 arrived outside the prison. The crowd chanted "Wilkes and Liberty", "No Liberty, No King", and "Damn the King! Damn the Government! Damn the Justices!". Fearing that the crowd would attempt to rescue Wilkes, the troops opened fire killing seven people. Anger at these events led to disturbances all over London. (24)

On 8th June 1768 Wilkes was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 22 months imprisonment and fined £1,000. Wilkes was also expelled from the House of Commons but in February, March and April, 1769, he was three times re-elected for Middlesex, but on all three occasions the decision was overturned by Parliament. In May the House of Commons voted that Colonel Henry Luttrell, the defeated candidate at Middlesex, should be accepted as the MP. John Horne Tooke and other supporters of Wilkes formed the Bill of Rights Society. At first the society concentrated on forcing Parliament to accept the will of the Middlesex electorate, however, the organisation eventually adopted a radical programme of parliamentary reform. (25)

In 1774 John Wilkes was elected Lord Mayor of London. He was also elected once again to represent Middlesex in the House of Commons. Wilkes campaigned for religious toleration and on 21st March, 1776, he introduced the first motion for parliamentary reform. Wilkes called for the redistribution of seats from the small corrupt boroughs to the fast growing industrial areas such as Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and Sheffield. Although not a supporter of universal suffrage, Wilkes argued that working men should have a share in the power to make laws. (26)

Equality and Democracy

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, contemplated the issue of democracy in his book, Discourse on Inequality (1754). He argued the economic system generated its own forms of law, property and government. Rousseau insisted that this system is a fraud perptrated by the rich on the poor to protect their privileges. This "destroyed natural liberty, established for all time the law of property and inequality... and for the benefit of a few ambitious men subjected the human race thenceforth to labour, servitude and misery." (27)

Tom Paine, the son of a Quaker corset maker, and a former excise officer from Lewes, strongly agreed with Rousseau, but believed that the system could be changed by political action. In 1777 he published Common Sense, a pamphlet that supported the American War of Independence. "The theme of the pamphlet was simple. Government by kings was indefensible. Government by kings from a foreign country was worse. Both had to be overthrown and replaced by representative parliaments." (28)

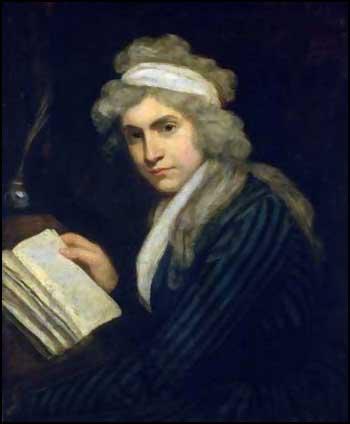

William Pitt wanted a career in politics "but being a younger son had no independent fortune". He therefore did not have the money to stand for a contested election and had to find a cheaper way to enter Parliament. With the help of his university friend, Charles Manners, 4th Duke of Rutland, secured the patronage of James Lowther, who controlled a pocket borough and at a by-election entered the House of Commons in January 1781. (29)

On 19th December 1783, George III appointed Pitt as Prime Minister, even though Lord North and Charles Fox continued to command majority support in the House of Commons. The dismissal by the King of a government with a clear majority, was unconstitutional and a total violation of the settlement of 1688. Pitt, at twenty-four, was by far the youngest Prime Minister in British history. (30)

In 1785 Pitt attempted to reform the House of Commons. His bill proposed to remove 36 rotten boroughs and create new seats for London. It also would also marginally extended the vote to people with estates in the counties worth 40 shillings or more. Parliament voted by 248 votes to 174 not to debate the bill. Even the Prime Minister could not persuade a Parliament to consider the mildest reform to the corruption that secured their seats. (31)

Thomas Paine continued to write on political issues and in 1791 published his most influential work, The Rights of Man. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. "The whole system of representation is now, in this country, only a convenient handle for despotism, they need not complain, for they are as well represented as a numerous class of hard-working mechanics, who pay for the support of royalty when they can scarcely stop their children's mouths with bread." (32)

The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. Paine also argued that a reformed Parliament would reduce the possibility of going to war. "Whatever is the cause of taxes to a Nation becomes also the means of revenue to a Government. Every war terminates with an addition of taxes, and consequently with an addition of revenue; and in any event of war, in the manner they are now commenced and concluded, the power and interest of Governments are increased. War, therefore, from its productiveness, as it easily furnishes the pretence of necessity for taxes and appointments to places and offices, becomes a principal part of the system of old Governments; and to establish any mode to abolish war, however advantageous it might be to Nations, would be to take from such Government the most lucrative of its branches. The frivolous matters upon which war is made show the disposition and avidity of Governments to uphold the system of war, and betray the motives upon which they act." (33)

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy. By the time he had died, it is estimated that over 1,500,000 copies of the book had been sold in Europe. (34)

Mary Wollstonecraft had been converted to Unitaranism by Richard Price. She read Paine's book and in response published Vindication of the Rights of Women. In the book Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." (35)

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. One critic described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing. (36)

Thomas Hardy, a shoemaker, also read The Rights of Man and in 1792 Hardy founded the London Corresponding Society. The aim of the organisation was to achieve the vote for all adult males. Early members included John Thelwall, John Horne Tooke, Joseph Gerrald, Olaudah Equiano and Maurice Margarot. As well as campaigning for the vote, the strategy was to create links with other reforming groups in Britain. The society passed a series of resolutions and after being printed on handbills, they were distributed to the public. These resolutions also included statements attacking the government's foreign policy. A petition was started and by May 1793, 6,000 members of the public had signed saying they supported the resolutions of the London Corresponding Society. (37)

Thomas Spence was a schoolmaster from Newcastle. Spence was strongly influenced by the writings of Tom Paine. and in December 1792 Spence moved to London and attempted to make a living by selling the works of Paine on street corners. He was arrested but soon after he was released from prison he opened a shop in Chancery Lane where he sold radical books and pamphlets.

In 1793 Spence started a periodical, Pigs' Meat. He said in the first edition: "Awake! Arise! Arm yourselves with truth, justice, reason. Lay siege to corruption. Claim as your inalienable right, universal suffrage and annual parliaments. And whenever you have the gratification to choose a representative, let him be from among the lower orders of men, and he will know how to sympathize with you." (38)

By the early 1800s Thomas Spence had established himself as the unofficial leader of those Radicals who advocated revolution. James Watson, was one of the men who worked very closely with Spence during this period. Spence did not believe in a centralized radical body and instead encouraged the formation of small groups that could meet in local public houses. At the night the men walked the streets and chalked on the walls slogans such as "Spence's Plan and Full Bellies" and "The Land is the People's Farm". In 1800 and 1801 the authorities believed that Spence and his followers were responsible for bread riots in London. However, they did not have enough evidence to arrest them.

Thomas Spence died in September 1814. He was buried by "forty disciples" who pledged that they would keep his ideas alive. They did this by forming the Society of Spencean Philanthropists. The men met in small groups all over London. These meetings mainly took place in public houses and they discussed the best way of achieving an equal society. Places used included the Mulberry Tree in Moorfields, the Carlisle in Shoreditch, the Cock in Soho, the Pineapple in Lambeth, the White Lion in Camden, the Horse and Groom in Marylebone and the Nag's Head in Carnaby Market. The government became very concerned about this group that they employed a spy, John Castle, to join the Spenceans and report on their activities. (39)

The Peterloo Massacre

In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer. The main objective of this new organisation was to obtain parliamentary reform and during the summer of 1819 it was decided to invite Major John Cartwright, Henry Orator Hunt and Richard Carlile to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The men were told that this was to be "a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone. I think by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country." Cartwright was unable to attend but Hunt and Carlile agreed and the meeting was arranged to take place at St. Peter's Field on 16th August. (40)

Samuel Bamford, a handloom weaver, walked from Middleton to be at the meeting that day: "Every hundred men had a leader, who was distinguished by a spring of laurel in his hat, and the whole were to obey the directions of the principal conductor, who took his place at the head of the column, with a bugleman to sound his orders. At the sound of the bugle not less than three thousand men formed a hollow square, with probably as many people around them, and I reminded them that they were going to attend the most important meeting that had ever been held for Parliamentary Reform. I also said that, in conformity with a rule of the committee, no sticks, nor weapons of any description, would be allowed to be carried. Only the oldest and most infirm amongst us were allowed to carry their walking staves. Our whole column, with the Rochdale people, would probably consist of six thousand men. At our head were a hundred or two of women, mostly young wives, and mine own was amongst them. A hundred of our handsomest girls, sweethearts to the lads who were with us, danced to the music. Thus accompanied by our friends and our dearest we went slowly towards Manchester." (41)

The local magistrates were concerned that such a substantial gathering of reformers might end in a riot. The magistrates therefore decided to arrange for a large number of soldiers to be in Manchester on the day of the meeting. This included four squadrons of cavalry of the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), a detachment of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (120 men) and all Manchester's special constables (400 men).

At about 11.00 a.m. on 16th August, 1819 William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field by midday. Hulton therefore took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying. (42)

The main speakers at the meeting arrived at 1.20 p.m. This included Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Richard Carlile, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and Mary Fildes. Several of the newspaper reporters, including John Tyas of The Times, Edward Baines of the Leeds Mercury, John Smith of the Liverpool Mercury and John Saxton of the Manchester Observer, joined the speakers on the hustings.

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". William Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest Henry Hunt and the other leaders of the demonstration. Nadin replied that this could not be done without the help of the military. Hulton then wrote two letters and sent them to Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange, the commander of the military forces in Manchester and Major Thomas Trafford, the commander of the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry.

Major Trafford, who was positioned only a few yards away at Pickford's Yard, was the first to receive the order to arrest the men. Major Trafford chose Captain Hugh Birley, his second-in-command, to carry out the order. Local eyewitnesses claimed that most of the sixty men who Birley led into St. Peter's Field were drunk. Birley later insisted that the troop's erratic behaviour was caused by the horses being afraid of the crowd. (43)

The Manchester & Salford Yeomanry entered St. Peter's Field along the path cleared by the special constables. As the yeomanry moved closer to the hustings, members of the crowd began to link arms to stop them arresting Henry Hunt and the other leaders. Others attempted to close the pathway that had been created by the special constables. Some of the yeomanry now began to use their sabres to cut their way through the crowd.

When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they arrested Henry Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson, George Swift, John Saxton, John Tyas, John Moorhouse and Robert Wild. As well as the speakers and the organisers of the meeting, Birley also arrested the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks." (44)

Samuel Bamford was another one in the crowd who witnessed the attack on the crowd: "The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads... On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled... A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises. In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again." (45)

Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange reported to William Hulton at 1.50 p.m. When he asked Hulton what was happening he replied: "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry? Disperse them." L'Estrange now ordered Lieutenant Jolliffe and the 15th Hussars to rescue the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry. By 2.00 p.m. the soldiers had cleared most of the crowd from St. Peter's Field. In the process, 18 people were killed and about 500, including 100 women, were wounded. (46)

Some historians have argued that Lord Liverpool, the prime minister, and Lord Sidmouth, his home secretary, were behind the Peterloo Massacre. However, Donald Read, the author of Peterloo: The Massacre and its Background (1958) disagrees with this interpretation: "Peterloo, as the evidence of the Home Office shows, was never desired or precipitated by the Liverpool Ministry as a bloody repressive gesture for keeping down the lower orders. If the Manchester magistrates had followed the spirit of Home Office policy there would never have been a massacre." (47)

E. P. Thompson disagrees with Read's analysis. He has looked at all the evidence available and concludes: "My opinion is (a) that the Manchester authorities certainly intended to employ force, (b) that Sidmouth knew - and assented to - their intention to arrest Hunt in the midst of the assembly and to disperse the crowd, but that he was unprepared for the violence with which this was effected." (48)

Richard Carlile managed to avoid being arrested and after being hidden by local radicals, he took the first mail coach to London. The following day placards for Sherwin's Political Register began appearing in London with the words: 'Horrid Massacres at Manchester'. A full report of the meeting appeared in the next edition of the newspaper. The authorities responded by raiding Carlile's shop in Fleet Street and confiscating his complete stock of newspapers and pamphlets. (49)

James Wroe was at the meeting and he described the attack on the crowd in the next edition of the Manchester Observer. Wroe is believed to be the first person to describe the incident as the Peterloo Massacre. Wroe also produced a series of pamphlets entitled The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events. The pamphlets, which appeared for fourteen consecutive weeks from 28th August, price twopence, had a large circulation, and played an important role in the propaganda war against the authorities. Wroe, like Carlile, was later sent to prison for writing these accounts of the Peterloo Massacre. (50)

Moderate reformers in Manchester were appalled by the decisions of the magistrates and the behaviour of the soldiers. Several of them wrote accounts of what they had witnessed. Archibald Prentice sent his report to several London newspapers. When John Edward Taylor discovered that John Tyas of The Times, had been arrested and imprisoned, he feared that this was an attempt by the government to suppress news of the event. Taylor therefore sent his report to Thomas Barnes, the editor of The Times. The article that was highly critical of the magistrates and the yeomanry was published two days later. (51)

Tyas was released from prison. The Times mounted a campaign against the action of the magistrates at St. Peter's Field. In one editorial the newspaper told its readers "a hundred of the King's unarmed subjects have been sabred by a body of cavalry in the streets of a town of which most of them were inhabitants, and in the presence of those Magistrates whose sworn duty it is to protect and preserve the life of the meanest Englishmen." As these comments came from an establishment newspaper, the authorities found this criticism particularly damaging.

Other journalists at the meeting were not treated as well as Tyas. Richard Carlile wrote an article on the Peterloo Massacre in the next edition of The Republican. Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. The authorities also disapproved of Carlile publishing books by Tom Paine, including Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to three years in Dorchester Gaol. (52)

Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated. Carlile was determined not to be silenced. While he was in prison he continued to write material for The Republican, which was now being published by his wife. Due to the publicity created by Carlile's trial, the circulation of The Republican increased dramatically and was now outselling pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (53)

In the first trial of those people who attended the meeting at St. Peter's Field, the judge commented: "I believe you are a downright blackguard reformer. Some of you reformers ought to be hanged, and some of you are sure to be hanged - the rope is already round your necks." (54)

Cato Street Conspiracy

The government remained concerned about the Spenceans and John Stafford, who worked at the Home Office, recruited George Edwards, George Ruthven, John Williamson, John Shegoe, James Hanley and Thomas Dwyer to spy on this group. The Peterloo Massacre in Manchester increased the amount of anger the Spenceans felt towards the government. At one meeting a spy reported that Arthur Thistlewood said: "High Treason was committed against the people at Manchester. I resolved that the lives of the instigators of massacre should atone for the souls of murdered innocents." (55)

On 22nd February 1820, George Edwards pointed out to Arthur Thistlewood an item in a newspaper that said several members of the British government were going to have dinner at Lord Harrowby's house at 39 Grosvenor Square the following night. Thistlewood argued that this was the opportunity they had been waiting for. It was decided that a group of Spenceans would gain entry to the house and kill all the government ministers. According to the reports of spies the heads of Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth would be placed on poles and taken around the slums of London. Thistlewood was convinced that this would incite an armed uprising that would overthrow the government. This would be followed by the creation of a new government committed to creating a society based on the ideas of Thomas Spence. (56)

Over the next few hours Thistlewood attempted to recruit as many people as possible to take part in the plot. Many people refused and according to the police spy, George Edwards, only twenty-seven people agreed to participate. This included William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, John Brunt, John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Strange, Charles Copper, Robert Adams and John Monument.

William Davidson had worked for Lord Harrowby in the past and knew some of the staff at Grosvenor Square. He was instructed to find out more details about the cabinet meeting. However, when he spoke to one of the servants he was told that the Earl of Harrowby was not in London. When Davidson reported this news back to Arthur Thistlewood, he insisted that the servant was lying and that the assassinations should proceed as planned. (57)

One member of the gang, John Harrison, knew of a small, two-story building in Cato Street that was available for rent. The ground-floor was a stable and above that was a hayloft. As it was only a short distance from Grosvenor Square, it was decided to rent the building as a base for the operation. Edwards told Stafford of the plan and Richard Birnie, a magistrate at Bow Street, was put in charge of the operation. Lord Sidmouth instructed Birnie to use men from the Second Battalion Coldstream Guards as well as police officers from Bow Street to arrest the Cato Street Conspirators. (58)

Birnie decided to send George Ruthven, a police officer and former spy who knew most of the Spenceans, to the Horse and Groom, a public house that overlooked the stable in Cato Street. On 23rd February, Ruthven took up his position at two o'clock in the afternoon. Soon afterwards Thistlewood's gang began arriving at the stable. By seven thirty Richard Birnie and twelve police officers joined Ruthven at Cato Street.

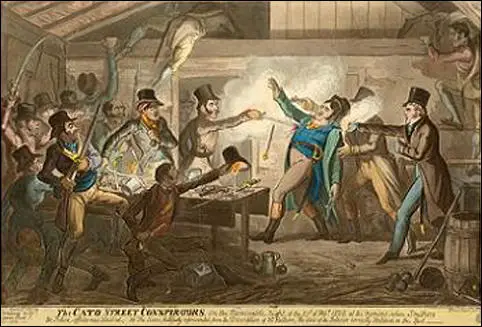

The Coldstream Guards had not arrived and Birnie decided he had enough men to capture the Cato Street gang. Birnie gave orders for Ruthven to carry out the task while he waited outside. Inside the stable the police found James Ings on guard. He was quickly overcome and George Ruthven led his men up the ladder into the hayloft where the gang were having their meeting. As he entered the loft Ruthven shouted, "We are peace officers. Lay down your arms." Arthur Thistlewood and William Davidson raised their swords while some of the other men attempted to load their pistols. One of the police officers, Richard Smithers, moved forward to make the arrests but Thistlewood stabbed him with his sword. Smithers gasped, "Oh God, I am..." and lost consciousness. Smithers died soon afterwards. (59)

Some of the gang surrendered but others like William Davidson were only taken after a struggle. Four of the conspirators, Thistlewood, John Brunt, Robert Adams and John Harrison escaped out of a back window. However, George Edwards had given the police a detailed list of all those involved and the men were soon arrested.

Eleven men were eventually charged with being involved in the Cato Street Conspiracy. After the experience of the previous trial of the Spenceans, Lord Sidmouth was unwilling to use the evidence of his spies in court. George Edwards, the person with a great deal of information about the conspiracy, was never called. Instead the police offered to drop charges against certain members of the gang if they were willing to give evidence against the rest of the conspirators. Two of these men, Robert Adams and John Monument, agreed and they provided the evidence needed to convict the rest of the gang.

James Ings claimed that George Edwards had worked as an agent provocateur: "The Attorney-General knows Edwards. He knew all the plans for two months before I was acquainted with it. When I was before Lord Sidmouth, a gentleman said Lord Sidmouth knew all about this for two months. I consider myself murdered if Edwards is not brought forward. I am willing to die on the scaffold with him. I conspired to put Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth out of this world, but I did not intend to commit High Treason. I did not expect to save my own life, but I was determined to die a martyr in my country's cause." (60)

William Davidson said in court: "It is an ancient custom to resist tyranny... And our history goes on further to say, that when another of their Majesties the Kings of England tried to infringe upon those rights, the people armed, and told him that if he did not give them the privileges of Englishmen, they would compel him by the point of the sword... Would you not rather govern a country of spirited men, than cowards? I can die but once in this world, and the only regret left is, that I have a large family of small children, and when I think of that, it unmans me." (61)

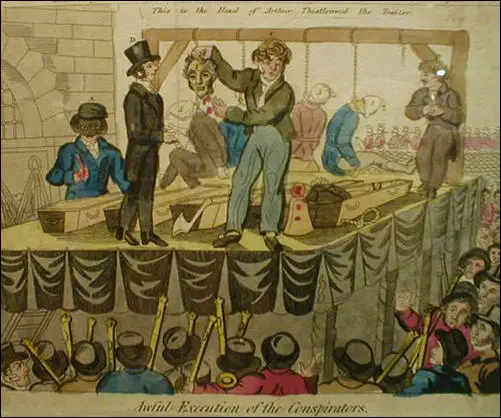

On 28th April 1820, Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Strange and Charles Copper were also found guilty but their original sentence of execution was subsequently commuted to transportation for life. (62)

Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt were taken to Newgate Prison on 1st May, 1820. John Hobhouse attended the execution: "The men died like heroes. Ings, perhaps, was too obstreperous in singing Death or Liberty" and records Thistlewood as saying, "Be quiet, Ings; we can die without all this noise." (63)

According to the author of An Authentic History of the Cato Street Conspiracy (1820). "Thistlewood struggled slightly for a few minutes, but each effort was more faint than that which preceded; and the body soon turned round slowly, as if upon the motion of the hand of death. Tidd, whose size gave cause to suppose that he would 'pass' with little comparative pain, scarcely moved after the fall. The struggles of Ings were great. The assistants of the executioner pulled his legs with all their might; and even then the reluctance of the soul to part from its native seat was to be observed in the vehement efforts of every part of the body. Davidson, after three or four heaves, became motionless; but Brunt suffered extremely, and considerable exertions were made by the executioners and others to shorten his agonies." (64)

Richard Carlile told the wife of William Davidson. "Be assured that the heroic manner in which your husband and his companions met their fate, will in a few years, perhaps in a few months, stamp their names as patriots, and men who had nothing but their country's weal at heart. I flatter myself as your children grow up, they will find that the fate of their father will rather procure them respect and admiration than its reverse." (65)

Six Acts

The government was greatly concerned by the dangers of the parliamentary reform movement and welcomed the action taken by the Manchester magistrates at St. Peter's Field. The Prince of Wales, the future King George IV, sent a message to the magistrates thanking them "for their prompt, decisive, and efficient measures for the preservation of the public peace". (66)

Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, sent a letter of congratulations to the Manchester magistrates for the action they had taken. He also sent a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action. This was supported by John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, who was of the clear opinion" that the meeting "was an overt act of treason". (67)

As Terry Eagleton has pointed out the "liberal state is neutral between capitalism and its critics until the critics look like they're winning." (68) When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection". (69)

(i) Training Prevention Act: A measure which made any person attending a gathering for the purpose of training or drilling liable to arrest. People found guilty of this offence could be transported for seven years.

(ii) Seizure of Arms Act: A measure that gave power to local magistrates to search any property or person for arms.

(iii) Seditious Meetings Prevention Act: A measure which prohibited the holding of public meetings of more than fifty people without the consent of a sheriff or magistrate.

(iv) The Misdemeanours Act: A measure that attempted to reduce the delay in the administration of justice.

(v) The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act: A measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious.

(vi) Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act: A measure which subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty.

Francis Place, one of the leaders of the reform movement, wrote that "I despair of being able adequately to express correct ideas of the singular baseness, the detestable infamy, of their equally mean and murderous conduct. They who passed the Gagging Acts in 1817 and the Six Acts in 1819 were such miscreants, they could they have acted thus in a well-ordered community they would all have been hanged." (70)

These measures were opposed by the Whigs as being a suppression of popular rights and liberties. They warned that it was unreasonable to pass national laws to deal with problems that only existed in certain areas. The Whigs also warned that these measures would encourage radicals to become even more rebellious. Earl Grey, the leader of the Whigs in the House of Commons, kept a low profile over the issue as he was "anxious to preserve the pre-eminence of the landed class... as many in his party profited from an undemocratic system of representation". (71)

The trial of the organisers of the St. Peter's Field meeting took place in York between 16th and 27th March, 1820. The men were charged with "assembling with unlawful banners at an unlawful meeting for the purpose of exciting discontent". Henry Orator Hunt was found guilty and was sent to Ilchester Gaol for two years and six months. Joseph Johnson, Samuel Bamford and Joseph Healey were each sentenced to one year in prison. (72)

John Edward Taylor was a successful businessman who was radicalized by the Peterloo Massacre. Taylor felt that the newspapers did not accurately record the outrage that the people felt about what happened at St. Peter's Fields. Taylor's political friends agreed and it was decided to form their own newspaper. Eleven men, all involved in the textile industry, raised £1,050 for the venture. It was decided to call the newspaper the Manchester Guardian. A prospectus was published which explained the aims and objectives of the proposed newspaper: "It will zealously enforce the principles of civil and religious Liberty, it will warmly advocate the cause of Reform; it will endeavour to assist in the diffusion of just principles of Political Economy." (73)

The first four-page edition appeared on Saturday 5th May, 1821 and cost 7d. Of this sum, 4d was a tax imposed by the government. The Manchester Guardian, like other newspapers at the time, also had to pay a duty of 3d a lb. on paper and three shillings and sixpence on every advertisement that was included. These taxes severely restricted the number of people who could afford to buy newspapers.

Two aspects of the Six Acts was to prevent the publication of radical newspapers. The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act was a measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious. The Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act was an attempt to subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty.

One of the most popular radical newspapers was the Black Dwarf with a circulation of about 12,000. Its editor was Thomas Jonathan Wooler. This was a period of time it was possible to make a living from being a radical publisher. "The means of production of the printed page were sufficiently cheap to mean that neither capital nor advertising revenue gave much advantage; while the successful Radicalism, for the first time, a profession which could maintain its own full-time agitators." (74)

After the passing of the Six Acts Wooler was arrested and charged with "forming a seditious conspiracy to elect a representative to Parliament without lawful authority". Wooler was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment. (75)

On his release from prison Wooler modified the tome of the Black Dwarf in an effort to comply with the terms of the Six Acts. As a result he lost circulation of those like Richard Carlile, the editor of The Republican, who refused to reduce his radicalism. This was a successful strategy and he was able to outsell pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (76)

To survive, Wooler had to rely on financial help from Major John Cartwright. However, on Cartwright's death on 23rd September 1824, he was forced to close the newspaper down. He wrote in the final edition that there was no longer a "public devotedly attached to the cause of parliamentary reform". Whereas in the past they had demanded reform, now they only "clamoured for bread". (77)

A Stamp Tax was first imposed on British newspapers in 1712. The tax was gradually increased until in 1815 it had reached 4d. a copy. As few people could afford to pay 6d. or 7d. for a newspaper, the tax restricted the circulation of most of these journals to people with fairly high incomes. During this period most working people were earning less than 10 shillings a week and this therefore severely reduced the number of people who could afford to buy radical newspapers.

Campaigners against the stamp tax such as William Cobbett and Leigh Hunt described it as a "tax on knowledge". As one of these editors pointed out: "Let us then endeavour to progress in knowledge, since knowledge is demonstrably proved to be power. It is the power knowledge that checks the crimes of cabinets and courts; it is the power of knowledge that must put a stop to bloody wars." (78)

1832 Reform Act

Between 1770 and 1830, the Tories were the dominant force in the House of Commons. The Tories were strongly opposed to increasing the number of people who could vote. However, in November, 1830, Earl Grey, a Whig, became Prime Minister. Grey explained to William IV that he wanted to introduce proposals that would get rid of some of the rotten boroughs. Grey also planned to give Britain's fast growing industrial towns such as Manchester, Birmingham, Bradford and Leeds, representation in the House of Commons. (79)

In March 1831 Grey introduced his reform bill. Princess Dorothea Lieven, the wife of the Russian ambassador, commented: "I was absolutely stupefied when I learnt the extent of the Reform Bill. The most absolutely secrecy has been maintained on the subject until the last moment. It is said that the House of Commons was quite taken by surprise; the Whigs are astonished, the Radicals delighted, the Tories indignant. This was the first impression of Lord John Russell's speech, who was entrusted with explaining the Government Bill. I have had neither the time nor the courage to read it. Its leading features have scared me completely: 168 members are unseated, sixty boroughs disfranchised, eight more members allotted to London and proportionately to the large towns and counties, the total number of members reduced by sixty or more." (80)

It was passed by the House of Commons. According to Thomas Macaulay: "Such a scene as the division of last Tuesday I never saw, and never expect to see again. If I should live fifty years the impression of it will be as fresh and sharp in my mind as if it had just taken place. It was like seeing Caesar stabbed in the Senate House, or seeing Oliver taking the mace from the table, a sight to be seen only once and never to be forgotten. The crowd overflowed the House in every part. When the doors were locked we had six hundred and eight members present, more than fifty five than were ever in a division before". (81)

The following month the Tories blocked the measure in the House of Lords. Grey asked William IV to dissolve Parliament so that the Whigs could show that they had support for their reforms in the country. Grey explained this would help his government to carry their proposals for parliamentary reform. William agreed to Grey's request and after making his speech in the House of Lords, walked back through cheering crowds to Buckingham Palace. (82)

Polling was held from 28th April to 1st June 1831. In Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended demonstrations in favour of parliamentary reform. William Lovett, the head of the National Union of the Working Classes, gave his support to the reformers standing in the election. The Whigs won a landslide victory obtaining a majority of 136 over the Tories. After Lord Grey's election victory, he tried again to introduce parliamentary reform. Enormous demonstrations took place all over England and in Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended these meetings. They were overwhelmingly composed of artisans and working men. (83)

On 22nd September 1831, the House of Commons passed the Reform Bill. However, the Tories still dominated the House of Lords, and after a long debate the bill was defeated on 8th October by forty-one votes. When people heard the news, Reform Riots took place in several British towns; the most serious of these being in Bristol in October 1831, when all four of the city's prisons were burned to the ground. In London, the houses owned by the Duke of Wellington and bishops who had voted against the bill in the Lords were attacked. On 5th November, Guy Fawkes was replaced on the bonfires by effigies of Wellington. (84)

Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, complained: "This detestable Reform Bill has raised the hopes of the utmost. At Plymouth and the neighbouring towns, the spirit is tremendously bad. The shopkeepers are almost all Dissenters, and such is the rage on the question of Reform at Plymouth, that I have received from several quarters the most earnest requests that I will not come to concentrate a church, as I had engaged to do. They assure me that my own person, and the security of the public peace, would be in the greatest danger." (85)

Lord Grey argued in the House of Commons that without reform he feared a violent revolution would take place: "There is no one more decided against annual parliaments, universal suffrage, and the ballot, than I am. My object is not to favour but to put an end to such hopes and projects." (86) The Poor Man's Guardian agreed and it commented that the ruling class felt that "a violent revolution is their greatest dread". (87)

Grey attempted negotiation with a group of moderate Tory peers, known as "the waverers", but failed to win them over. On 7th May a wrecking amendment was carried by thirty-five votes, and on the following day the cabinet resolved to resign unless the king would agree to the creation of peers. On 7th May 1832, Earl Grey and Henry Brougham met the king and asked him to create a large number of Whig peers in order to get the Reform Bill passed in the House of Lords. William was now having doubts about the wisdom of parliamentary reform and refused. (88)

Lord Grey's government resigned and William IV now asked the leader of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington, to form a new government. Wellington tried to do this but some Tories, including Sir Robert Peel, were unwilling to join a cabinet that was in opposition to the views of the vast majority of the people in Britain. Peel argued that if the king and Wellington went ahead with their plan there was a strong danger of a civil war in Britain. He argued that Tory ministers "have sent through the land the firebrand of agitation and no one can now recall it." (89)

When the Duke of Wellington failed to recruit other significant figures into his cabinet, William was forced to ask Grey to return to office. In his attempts to frustrate the will of the electorate, William IV lost the popularity he had enjoyed during the first part of his reign. Once again Lord Grey asked the king to create a large number of new Whig peers. William agreed that he would do this and when the Lords heard the news, they agreed to pass the Reform Act. According to the Whig MP, Thomas Creevey, by taking this action, Grey "has saved the country from confusion, and perhaps the monarch and monarchy from destruction". (90)

Creevey went on to state that it was a great victory against the Tories: "Thank God! I was in at the death of this Conservative plot, and the triumph of the Bill! This is the third great event of my life at which I have been present, and in each of which I have been to a certain extent mixed up - the battle of Waterloo, the battle of Queen Caroline, and the battle of Earl Grey and the English nation for the Reform Bill." (91)

A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has argued that the most import change was that it placed "political power in the hands of the industrial capitalists and their middle class followers." (92) Karl Marx believed that this reform was an example of when one class rules on behalf of another. He pointed out that "the Whig aristocracy was still the governing political class, while the industrial middle class was increasingly the dominant economic one; and the former, generally speaking, represented the interests of the latter." (93)

Most people were disappointed with the 1832 Reform Act. Voting in the boroughs was restricted to men who occupied homes with an annual value of £10. There were also property qualifications for people living in rural areas. As a result, only one in seven adult males had the vote. Nor were the constituencies of equal size. Whereas 35 constituencies had less than 300 electors, Liverpool had a constituency of over 11,000. "The overall effect of the Reform Act was to increase the number of voters by about 50 per cent as it added some 217,000 to an electorate of 435,000 in England and Wales. But 650,000 electors in a population of 14 million were a small minority." (94)

Moral Force Chartism

Many working people were disappointed when they realised that the 1832 Reform Act did not give them the vote. This disappointment turned to anger when the reformed House of Commons passed the 1834 Poor Law. In June 1836 William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands. (95)

"(1) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

(2) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (2) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (3) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (4) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (5) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period." (96)

When supporters of parliamentary reform held a convention the following year, Lovett was chosen as the leader of the group that were now known as the Chartists. The four main leaders of the Chartist movement had been involved in political campaigns for many years and had all experienced periods of imprisonment. However, they were all strongly opposed to using any methods that would result in violence. Reverend Benjamin Parsons argued: "Do it by moral means alone. Not a pike, a blunderbuss, a brick-bat, or a match, must be found in your hands. In physical force your opponents are mightier than you but in moral force you are ten thousand times stronger than they." (97)

Members of the House of Commons who supported the Chartists such as Thomas Attwood, Thomas Wakely, Thomas Duncombe and Joseph Hume constantly emphasized the need to use moral rather than physical force. Lovett, the acknowledged leader of the movement, wrote of how Chartists should "inform the mind" rather than "captivate the senses". Lovett argued that Chartism intended to succeeded through discussion and publication and "without commotion or violence". Moral Force Chartists believed that peaceful methods of persuasion such as the holding of public meetings, the publication of newspapers and pamphlets and the presentation of petitions to the House of Commons would finally convince those in power to change the parliamentary system. (98)

Chartists, including Henry Hetherington, James Watson, John Cleave, George Julian Harney and James O'Brien joined people like Richard Carlile in the fight against stamp duty. As these radical publishers refused to pay stamp-duty on their newspapers, this resulted in fines and periods of imprisonment. In 1835 the two leading unstamped radical newspapers, the Poor Man's Guardian, and The Cleave's Police Gazette, were selling more copies in a day than The Times sold all week and the Morning Chronicle all month. It was estimated at the time that the circulation of leading six unstamped newspapers had now reached 200,000. (99)

These newspapers had no problems finding people willing to sell these newspapers. Joseph Swann sold unstamped newspapers in Macclesfield. He was arrested and in court he was asked if he had anything to say in his defence: "Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications." The judge responded by sentencing him to three months hard labour. (100)

Physical Force Chartism

Feargus O'Connor was active in the Chartist movement. However, he was critical of leaders such as William Lovett and Henry Hetherington who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor argued that the concessions the chartists demanded would not be conceded without a fight, so there had to be a fight. (101)

O'Connor decided that he needed a newspaper to promote this new strategy. The first edition of the Northern Star was published on 26th May, 1838. The newspaper contained reports on Chartist meets all over Britain and its letter's page enabled supporters to join the debate on parliamentary reform. O'Connor's newspaper also spearheaded the campaign in support of those skilled workers such as handloom weavers who had suffered the consequences of new technology. Within four months of starting publication, the newspaper was selling 10,000 copies a week. By the summer of 1839 circulation of the newspaper reached over 50,000 a week and O'Connor claimed a weekly readership of 400,000. (102)

In May 1838 Henry Vincent was arrested for making inflammatory speeches. When he was tried on the 2nd August at Monmouth Assizes he was found guilty and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment. John Frost organised a demonstration against Vincent's conviction. It is estimated that over 3,000 marchers arrived in Newport on 4th November 1839. They discovered that the authorities had made more arrests and were holding several Chartists in the Westgate Hotel. The Chartists marched to the hotel and began chanting "surrender our prisoners". Twenty-eight soldiers had been placed inside the Westgate Hotel and when the order was given they began firing into the crowd. Afterwards it was estimated that over twenty men were killed and another fifty were wounded. (103)

Frost and others involved in the march on Newport were arrested and charged with high treason. Several of the men, including Frost, were found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. The severity of the sentences shocked many people and protests meetings took place all over Britain. The British Cabinet discussed the sentences and on 1st February the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, announced that instead of the men being executed they would be transported for life. Frost was sent to Tasmania where he worked for three years as a clerk and eight years as a school teacher. (104)

Other supporters of Physical Force such as James Rayner Stephens and George Julian Harney were imprisoned during 1839. Feargus O'Connor was also arrested and in March 1840 he was tried at York for publishing seditious libels in the Northern Star. O'Connor defended himself in a marathon speech of over five hours. He told the jury, "I shall establish my innocence, if not to your satisfaction, to the satisfaction, I trust, of the rest of the world." He was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment. (105)

After his release from prison in August 1841, Feargus O'Connor took control of the National Charter Association. His vicious attacks on other Chartist leaders such as Thomas Attwood, William Lovett, Bronterre O'Brien and Henry Vincent split the movement. Some like Attwood and Lovett, who were unwilling to be associated with O'Connor's threats of violence, decided to leave the organisation. (106)

On 10th April 1848, O'Connor organised a large meeting at Kennington Common and then presented a petition to the House of Commons that he claimed contained 5,706,000 signatures. However, when it was examined by MPs it only had 1,975,496, signatures and many of these were clear forgeries. Moral Force Chartists accused O'Connor of destroying the credibility of the Chartist movement. (107)

William Cuffay, the son of a former slave, and one of the leaders of the London Chartists, called for a General Strike. Cuffay, like George Julian Harney, believed this would eventually result in an armed rising. A government spy called Powell joined Cuffay's group in London. Based on the evidence acquired by Powell, Cuffay was arrested and convicted and sentenced to be transported to Tasmania for 21 years. (108)

The failure of the April 10th demonstration severely damaged the Chartist movement. In some areas Physical Force Chartism still remained strong. A meeting addressed by Feargus O'Connor in Leicester in 1850 was attended by 20,000 people. There were also large meetings in London and Birmingham. However, the revival of trade reduced the amount of dissatisfaction with the parliamentary system. Chartist candidates did very badly in the 1852 General Election and sales of the Northern Star dropped to 1,200. By the time Feargus O'Connor died in 1855, the Chartist movement had come to an end. (109)

1867 Reform Act

In March 1860 Lord John Russell attempted to introduce a new Parliamentary Reform Act that would reduce the qualification for the franchise to £10 in the counties and £6 in towns, and effecting a redistribution of seats. Lord Palmerston, the prime minister, was opposed to parliamentary reform, and with his lack of support, the measure did not become law. On the death of Palmerston in July 1865, Earl Russell (he had been raised to the peerage in July 1861) became prime minister. Russell, with the once again tried to persuade Parliament to accept the reforms that had been proposed in 1860. The measure receive little support in Parliament and was not passed before Russell's resignation in June 1866. (110)

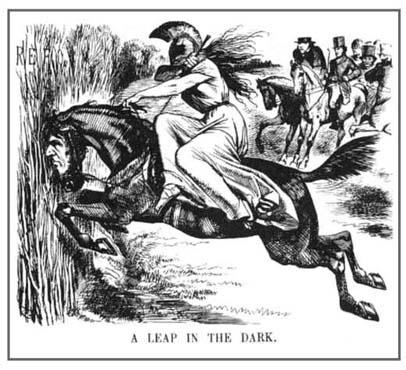

William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that like Earl Russell, he was also in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, Lord Derby's new government were now sympathetic to the idea. The Conservatives knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later Lord Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy." (111)

In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (112)

1872 Reform Act (Secret Ballot)

After the passing of the 1867 Reform Act working class males now formed the majority in most borough constituencies. However, employers were still able to use their influence in some constituencies because of the open system of voting. In parliamentary elections people still had to mount a platform and announce their choice of candidate to the officer who then recorded it in the poll book. Employers and local landlords therefore knew how people voted and could punish them if they did not support their preferred candidate.

In 1872 William Gladstone removed this intimidation when his government brought in the Ballot Act which introduced a secret system of voting. Paul Foot points out: "At once, the hooliganism, drunkenness and blatant bribery which had marred all previous elections vanished. employers' and landlords' influence was still brought to bear on elections, but politely, lawfully, beneath the surface." (113)

1884 Reform Act

The 1867 Reform Act had granted the vote to working class males in the towns but not in the counties. William Gladstone and most members of the Liberal Party argued that people living in towns and in rural areas should have equal rights. Lord Salisbury, leader of the Conservative Party, opposed any increase in the number of people who could vote in parliamentary elections. Salisbury's critics claimed that he feared that this reform would reduce the power of the Tories in rural constituencies.

In 1884 Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. The bill faced serious opposition in the House of Commons. The Tory MP, William Ansell Day, argued: "The men who demand it are not the working classes... It is the men who hope to use the masses who urge that the suffrage should be conferred upon a numerous and ignorant class." (114)

The bill was passed by the Commons but was rejected by the Conservative dominated House of Lords. Gladstone refused to accept defeat and reintroduced the measure. This time the Conservative members of the Lords agreed to pass Gladstone's proposals in return for the promise that it would be followed by a Redistribution Bill. Gladstone accepted their terms and the 1884 Reform Act was allowed to become law. This measure gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs - adult male householders and £10 lodgers - and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. (115)

However, this legislation meant that all women and 40% of adult men were still without the vote. According to Lisa Tickner: "The Act allowed seven franchise qualifications, of which the most important was that of being a male householder with twelve months' continuous residence at one address... About seven million men were enfranchised under this heading, and a further million by virtue of one of the other six types of qualification. This eight million - weighted towards the middle classes but with a substantial proportion of working-class voters - represented about 60 per cent of adult males. But of the remainder only a third were excluded from the register of legal provision; the others were left off because of the complexity of the registration system or because they were temporarily unable to fulfil the residency qualifications... Of greater concern to Liberal and Labour reformers... was the issue of plural voting (half a million men had two or more votes) and the question of constituency boundaries." (116)

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news that women were still unable to vote and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Similar Women's Suffrage groups were formed all over Britain. One of the most important of these was in Manchester, where Lydia Becker emerged as a significant figure in the movement. In 1887 seventeen of these individual groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

Representation of the People Act 1918

Even after the passing of the Third Reform Act in 1884, only 60% of male householders over the age of 21 had the vote. The Russian Revolution in 1917 had shocked the British government. Large numbers of those fighting in the First World War also did not have the vote. It was therefore decided to allow all men over 21 to vote in future elections. The government also decided that certain categories of women over 30 who met property qualifications. The enfranchisement of this latter group was accepted as recognition of the contribution made by women defence workers. However, women were still not politically equal to men, who could vote from the age of 21. (117)

The size of the electorate tripled from the 7.7 million who had been entitled to vote in 1912 to 21.4 million by the end of 1918. Women now accounted for about 43% of the electorate. Had women been enfranchised based upon the same requirements as men, they would have been in the majority because of the loss of men in the war. This may explain why the government decided that women would be allowed to vote until the age of 30.

Charlotte Despard, aged 83, had been campaigning for the vote for many years and remarked at a meeting of the Women's Freedom League: "I have seen great days, but this is the greatest. I remember when we started twenty-one years ago, with empty coffers… I never believed that equal votes would come in my lifetime. But when an impossible dream comes true, we must go on to another. The true unity of men and women is one such dream. The end of war, of famine - they are all impossible dreams, but the dream must be dreamed until it takes a spiritual hold." (118)