On this day on 30th November

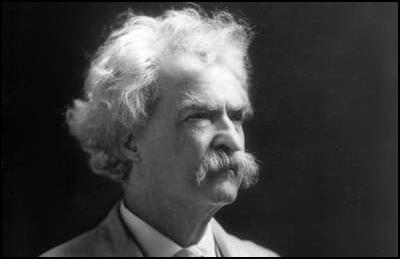

On the day in 1835 Samuel Langhorne Clemens, the son of a lawyer, was born in Florida, Missouri. His father died when Samuel was 12 and soon after found work as an apprentice compositor. In 1853 he moved to St. Louis and over the next few years worked in the printing trade in Chicago, New York City and Philadelphia.

When he was 22 he became a steamboat river pilot and during the American Civil War, a soldier in the Confederate Army. After prospecting for silver in Nevada he became a journalist in Virginia City. He now adopted the pen name Mark Twain and moved to San Francisco where he came under the influence of Bret Harte, the editor of the Overland Monthly. Twain later claimed that Harte "trimmed and trained and schooled me from an awkward utterer of coarse grotesqueness to a writer of paragraphs and chapters." His first story that brought him national fame was The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (1865).

In 1867 Twain travelled to Europe and this resulted in the book The Innocents Abroad (1869). He returned to the United States and married Olivia Langdon. After a period as the editor of the Buffalo Express, he moved to Hartford, Connecticut, where he lived for the next twenty years. A humorous account of his travels to Nevada, Roughing It, appeared in 1872.

Twain's boyhood memories of life beside the Mississippi, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, was published in 1876. This was followed by The Prince and The Pauper (1882). Twain's account of his steamboat experiences appeared in the Atlantic Monthly and these were expanded into the book Life on the Mississippi (1883).

Twain was now one of America's favourite writers and he had a series of best-sellers including A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889), The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), Tom Sawyer Abroad (1894) and Tom Sawyer, Detective (1896).

After Twain's publishing company went bankrupt and the death of one daughter, and the incurable illness of another, Twain's writing became increasingly pessimistic and this began to alienate him from his readers. The Man that Corrupted Hadleyburg (1900), King Leopold's Soliloquy (1905), What is a Man? (1906) and Eve's Diary (1906), written after the death of his wife, sold poorly compared to his earlier books. Mark Twain died on 21st April, 1910.

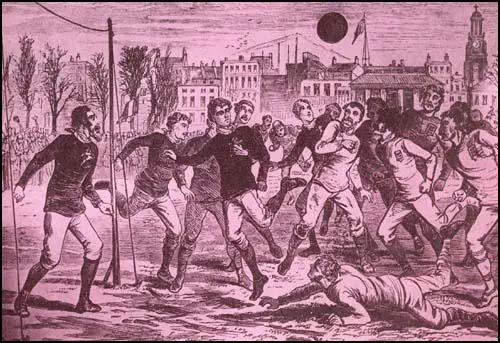

On the day in 1872 the first-ever international football match between Scotland and England. Charles W. Alcock, the secretary of the Football Association, took a team of English born players to play against a team from Scotland. The match, played in Glasgow, ended in a 0-0 draw. The main objective was to publicize the game of football in Scotland. It had the desired effect and the following year the Scottish Football Association was formed and the England-Scotland match became an annual fixture.

On the day in 1879 John Roebuck died of a heart-attack. Roebuck, the son of Ebenezer Roebuck, a civil servant in the East India Company, was born in Madras in India on 28th December, 1802. When John's father died in 1807 his mother brought the family back to England. She remarried and in 1815 John was taken to Canada to live.

Roebuck returned to England at the age of twenty-two to study law at the Inner Temple in London. He joined the Utilitarian Society became friendly with John Stuart Mill. Roebuck became active in the campaign for increasing the franchise and after the 1832 Reform Act was selected to represent the Whigs at Bath.

After entering the House of Commons he caused a stir by promoting a wide-range of radical policies including the expropriation of the property of the Church of England. Although accused of preaching open rebellion he retained his Bath seat in the 1835 General Election.

In 1834 Roebuck led the campaign to free the Tolpuddle Martyrs and called for the repeal of the Corn Laws. Roebuck joined with Francis Place and Joseph Hume to produce a volume of essays entitled Pamphlets for the People (1835). In one of these pamphlets, The Stamped Press and its Morality, Roebuck attacked the 1815 Stamp Act that had placed a 4d tax on newspapers. Roebuck criticised those newspaper owners who accepted this law. The editor of the Morning Chronicle was so upset he challenged Roebuck to a duel. Roebuck accepted and survived and later that year welcomed the decision to reduce the tax to one penny.

In June 1836, John Roebuck joined forces with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave, Henry Vincent and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands.

(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

(ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period."

John Roebuck had now completely broken with the Whigs and described them as "an exclusive and aristocratic faction, though at times employing democratic principles and phrases as weapons of offence against their opponents. When out of office they are demagogues; in power they become exclusive oligarchs." Without the support of the Whigs, Roebuck lost his Bath seat in the 1837 General Election.

Out of the House of Commons Roebuck's views became less extreme and in the 1841 General Election won Bath again. He supported the reforms of Robert Peel, but he remained radical on some issues and spoke out in favour of the Chartist movement and helped present their petition to Parliament in 1842.

Defeated at Bath in the 1847 General Election, Roebuck moved to Sheffield and was re-elected to the House of Commons in a by-election in 1849. Roebuck upset his radical friends by losing interest in domestic reform. After his election he supported the aggressive foreign policy of Lord Palmerston. This was popular with his constituents and he was re-elected in 1852, 1857, 1859 and 1865.

The views expressed by John Roebuck became increasingly conservative. He admitted in 1864 that: "the hopes of my youth and manhood are destroyed and I am left to reconstruct my political philosophy". Although a long-term supporter of universal suffrage, during the debate on the 1867 Reform Act he warned against placing political power "in the hands of the ignorant".

Roebuck denounced the activities of trade unionists in what became known as the Sheffield Outrages and opposed his party leader, William Gladstone, when he attempted to disestablish the Anglican Church in Ireland. By this time the members of the Liberal Party in Sheffield were totally disillusioned with Roebuck and selected another candidate for the forthcoming parliamentary election. Roebuck stood as an Independent but was easily defeated in the 1868 General Election.

With the support of the Conservative Party, Roebuck won the Sheffield seat in the 1874 General Election. In the House of Commons he denounced William Gladstone as a "bastard philanthropist" and praised the policies of Benjamin Disraeli.

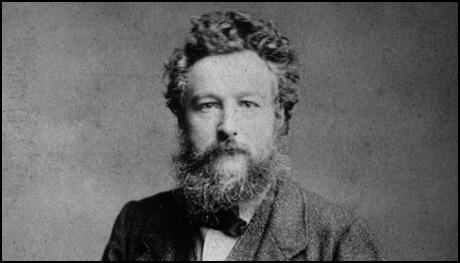

On the day in 1884 William Morris publishes an article for Commonweal calling for social reform. In December, 1884, William Morris, Walter Crane, Eleanor Marx, Ernest Belfort Bax and Edward Aveling left the Social Democratic Federation and formed the Socialist League. Strongly influenced by the ideas of Morris, the party published a manifesto where it advocated revolutionary international socialism.

William Morris believed that the main function of all socialist organisations was to "educate the people". It was therefore decided that the Socialist League should publish a journal called Commonweal. Financed by a £300 loan from Morris, the monthly paper first appeared in February 1885 declaring that it had "one aim - the propagation of Socialism". The first edition of Commonweal had eight 15 by 10 inch pages and sold over 5,000 copies.

Morris wrote an article on 30th November 1884: "Take courage, and believe that we of this age, in spite of all its torment and disorder, have been born to a wonderful heritage fashioned of the work of those that have gone before us; and that the day of the organization of man is dawning. It is not we who can build up the new social order; the past ages have done the most of that work for us; but we can clear our eyes to the signs of the times, and we shall then see that the attainment of a good condition of life is being made possible for us, and that it is now our business to stretch out our hands and take it. And how? Chiefly, I think, by educating people to a sense of their real capacities as men, so that they may be able to use to their own good the political power which is rapidly being thrust upon them; to get them to see that the old system of organizing labour for individual profit is becoming unmanageable, and that the whole people have now got to choose between the confusion resulting from the breakup of that system and the determination to take in hand the labour now organized for profit, and use its organization for the livelihood of the community: to get people to see that individual profit-makers are not a necessity for labour but an obstruction to it, and that not only or chiefly because they are the perpetual pensioners of labour, as they are, but rather because of the waste which their existence as a class necessitates. All this we have to teach people, when we have taught ourselves; and I admit that the work is long and burdensome; as I began by saying, people have been made so timorous of change by the terror of starvation that even the unluckiest of them are stolid and hard to move. Hard as the work is, however, its reward is not doubtful. The mere fact that a body of men, however small, are banded together as Socialist missionaries shows that the change is going on. As the working classes, the real organic part of society, take in these ideas, hope will arise in them, and they will claim changes in society, many of which doubtless will not tend directly towards their emancipation, because they will be claimed without due knowledge of the one thing necessary to claim, equality of condition; but which indirectly will help to break up our rotten sham society, while that claim for equality of condition will be made constantly and with growing loudness till it must be listened to, and then at last it will only be a step over the border, and the civilized world will be socialized; and, looking back on what has been, we shall be astonished to think of how long we submitted to live as we live now."

On the day in 1900 Oscar Wilde died. In 1895 Wilde was found guilty and sentenced to two years' penal servitude with hard labour four offences under the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885). Richard Haldane, under instructions from Herbert Gladstone, visited Oscar Wilde in Pentonville Prison on 12th June, 1895. Haldane managed to arrange for Wilde to gain access to books. Wilde was transferred to Wandsworth Prison on 4th July. His friend, Robert Sherrard, visited Wilde on behalf of Constance Wilde, and urged him to repudiate his homosexual friends. In November he was moved to Reading Prison.

Wilde's health deteriorated while in prison. He received little sympathy from the prison doctor, Oliver Calley Maurice (1838–1907). Wilde petitions to the home secretary asking for release on medical grounds were ignored on Maurice's advice. Wilde was not the only victim of Maurice's medical knowledge. In a letter to The Daily Chronicle, he argued that the prisoners were in mortal danger from Maurice: "It is a horrible duel between himself and the doctor. The doctor is fighting for a theory. The man is fighting for his life. I am anxious that the man should win."

Alfred Douglas remained loyal to Wilde and wrote letters to the newspapers and unsuccessfully petitioned Queen Victoria for clemency for his lover. He also wrote to Truth Magazine: "I personally know forty or fifty men who practise these acts. Men in the best society, members of the smartest clubs, members of Parliament, Peers, etc., in fact people of my own social standing... At Oxford, where I suppose you would admit one is likely to find the pick of the youth of England, I knew hundreds who had these tastes among the undergraduates, not to mention a slight sprinkling of Dons.... These tastes are perfectly natural congenital tendencies in certain people (a very large minority), and that the law has no right to interfere with these people, provided they do not harm other people; that is to say when there is neither seduction of minors nor brutalisation, and where there is no public outrage on morals."

In March 1897, Wilde wrote to Douglas about the death of his mother: "No one knew how deeply I loved and honoured her. Her death was terrible to me; but I, once a lord of language, have no words in which to express my anguish and my shame. She and my father had bequeathed me a name they had made noble and honoured, not merely in literature, art, archaeology, and science, but in the public history of my own country, in its evolution as a nation. I had disgraced that name eternally. I had made it a low by-word among low people. I had dragged it through the very mire. I had given it to brutes that they might make it brutal, and to fools that they might turn it into a synonym for folly."

G. A. Cevasco has argued: "Douglas's loyalty to the imprisoned Wilde, his financial generosity, and continued concern, must be viewed in the context of a turbulent relationship involving two highly self-centred and opinionated individuals." Upon Wilde's release from prison in 1897, he took up with Douglas once again. The two men lived together for a while in Naples and after they they met frequently in Paris. Douglas also helped Wilde financially.

An edited version of De Profundis was published in 1897. Owen Dudley Edwards has argued: "It did not deny his own culpability for the wreck of his and his family's lives, but it made his obsession with Douglas the leading count in his own self-indictment. It attacked Douglas for hatred of his father, acknowledged his love for Wilde, but saw that love, like Wilde himself, enslaved in the work of hate. Ross was held up as a model of friendship and stimulus. Yet the power and profundity of De Profundis itself asserted Douglas's far more cataclysmic inspirational effect. Nor was the contrast accurate in all respects. Both Ross and Douglas were demanding, self-centred, and indiscreet, and Wilde's relationship to both of them was more that of an indulgent but exploited uncle than of the physical lover he seems to have been for a relatively brief time in each case. Both Ross and Douglas were homosexual liberationists, Ross more constructively, Douglas more flamboyantly."

In 1898 Wilde published The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a poem inspired by his prison experiences. It included an account of the hanging of Charles Thomas Wooldridge (1866–1897), a trooper of the Royal Horse Guards, who had murdered his wife while suffering from mental illness. G. K. Chesterton described the poem as "a cry for common justice and brotherhood very much deeper, more democratic" than other forms of protest.

Augustus John, Charles Conder and William Rothenstein went to Paris to visit Wilde. John later recalled: " I had heard a lot about Oscar, of course, and on meeting him was not in the least disappointed, except in one respect: prison discipline had left one, and apparently only one, mark on him, and that not irremediable: his hair was cut short... We assembled first at the Cafe de la Regence.... The Monarch of the dinner-table seemed none the worse for his recent misadventures and showed no sign of bitterness, resentment or remorse. Surrounded by devout adherents, he repaid their hospitality by an easy flow of practised wit and wisdom, by which he seemed to amuse himself as much as anybody. The obligation of continual applause I, for one, found irksome. Never, I thought, had the face of praise looked more foolish."

Constance Wilde died on 7th April 1898. Wilde returned to his earlier religious beliefs and went to Rome and received the blessing of Leo XIII in April 1900. Suffering from meningitis he went to stay at the Hôtel d'Alsace. Before he became unconscious he remarked: "I am dying beyond my means". An Irish priest, Cuthbert Dunne, obtained by Robert Ross, gave him extreme unction and absolution on 29th November, 1900. Oscar Wilde died the next day and was buried in the Cimetière de Bagneux outside Paris.

On the day in 1906 women's rights campaigner Mary Bateson died. Mary was the daughter of William Henry Bateson and his wife, Anna Aikin, was born on 12th September 1865. Her father was master of St John's College. However, she was greatly influenced by her mother who was a strong promoter of women's rights.

Bateson attended the Misses Thornton's school in Cambridge before spending a year at the Institut Friedländer in Baden, Germany. She entered Newnham College in 1884, taking a first class in the historical tripos at the University of Cambridge in 1887. As her biographer, Mary Dockray-Miller, has pointed out: "Bateson remained a member of the Newnham community for the rest of her life as an associate, lecturer, and fellow of the college."

Bateson was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1888 she became the Cambridge organiser of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. Over the next few months she organised meetings in Norwich, Great Yarmouth, Bury St. Edmunds, King's Lynn and Lowestoft. The following year she was elected to the executive committee of the Cambridge Women's Suffrage Association.

In 1889 she was appointed as a lecturer on English constitutional history at Newnham College. She served on the college council, and took part in the unsuccessful effort of 1895–7 to have women admitted to full membership of the University of Cambridge. In 1903 Bateson was awarded a Newnham research fellowship. Upon the expiry of her fellowship she gave the money back to the fund to assist other scholars.

Bateson was a frequent contributor to the English Historical Review. She also provided 108 biographical articles to the original edition of the Dictionary of National Biography. As Mary Dockray-Miller has pointed out: "The subjects of all these entries are men; they include saints, monks, and noblemen. Some date to the Anglo-Saxon or early modern periods; most cluster in the Anglo-Norman and high middle ages."

In October 1903, one of her former students, Flora Mayor, experienced a terrible tragedy when the man she was engaged to marry, died in India. Mary Bateson wrote to Flora: "I heard from Alice Gardner today. I can't invent one single word or thought of consolation, and I can't pretend. Try not to mourn too terribly... Many of us stumble along without meeting the one co-soul; to have known that there was such an one, and what life could hold, can't have been a thing to crush and blight you utterly and for ever: I mean somehow or other you must live upon the riches you have got within you."

Thomas Frederick Tout, the historian, commented that she "was popular socially in circles that cared little for her personal (academic) distinction" and referred to her "rare sense of humour… her deep, hearty laugh… and her downright breezy good-fellowship".

On 19th May 1906 she took part in the deputation to the Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, representing "women who are doctors of letters, science and law in the universities of the United Kingdom and of the British colonies, in the universities also of Europe and the United States". This petition was signed by 1,530 women graduates "who believe the disenfranchisement of one sex to be injurious to both, and a national wrong in a country which pretends to be governed on a representative system". Mandell Creighton, the Bishop of London, tried to persuade her to give up her work as a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies with the words "that her main business in life was to... pursue a scholar's career."

Mary Bateson died from a brain haemorrhage, at the Nursing Hostel, Cambridge, on 30th November 1906. Bertrand Russell wrote "she will be a terrible loss to Newnham and to Cambridge … I respected and admired her very much indeed. She was the last person one would have thought of as likely to die."

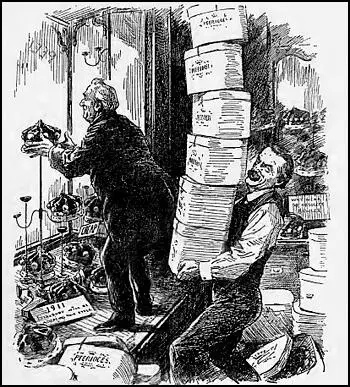

On the day in 1909 the House of Lords reject David Lloyd George's war Finance Bill by 350 votes to 75. H. H. Asquith had no option but to call a general election. In January 1910, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Asquith increased his own majority in East Fife but he was prevented from delivering his acceptance speech by members of the Women Social & Political Union who were demanding "Votes for Women".

John Grigg, the author of The People's Champion (1978) argues that the reason why the "people failed to give a sweeping, massive endorsement to the People's Budget" was that the electorate in 1910 was "by no means representative of the whole British nation". He points out that "only 58 per cent of adult males had the vote, and it is a fair assumption that the remaining 42 per cent would, if enfranchised, have voted in very large numbers for Liberal or Labour candidates. In what was still a disproportionately middle-class electorate the fear of Socialism was strong, and many voters were susceptible to the argument that the Budget was a first installment of Socialism."

Some of his critics on the left of the party believed that Asquith had not mounted a more aggressive campaign against the House of Lords. It was argued that instead of threatening its power to veto legislation, he should have advocated making it a directly elected second chamber. Asquith felt this was a step to far and was more interested in a negotiated settlement. However, to Colin Clifford, this made Asquith look "weak and indecisive".

In a speech on 21st February, 1910, H. H. Asquith outlined his plans for reform: "Recent experience has disclosed serious difficulties due to recurring differences of strong opinion between the two branches of the Legislature. Proposals will be laid before you, with convenient speed, to define the relations between the Houses of Parliament, so as to secure the undivided authority of the House of Commons over finance and its predominance in legislation."

The Parliament Bill was introduced later that month. "Any measure passed three times by the House of Commons would be treated as if it had been passed by both Houses, and would receive the Royal Assent... The House of Lords was to be shorn absolutely of power to delay the passage of any measure certified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as a money bill, but was to retain the power to delay any other measure for a period of not less than two years."

Edward VII died in his sleep on 6th May 1910. His son, George V, now had the responsibility of dealing with this difficult constitutional question. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the new king and had an "exceedingly frank and satisfactory talk about the political crisis". He told his wife that he was not very intelligent as "there's not much in his head". However, he "expressed the desire to try his hand at conciliation... whether he will succeed is somewhat doubtful."

James Garvin, the editor of The Observer, argued it was time that the government reached a negotiated settlement with the House of Lords: "If King Edward upon his deathbed could have sent a last message to his people, he would have asked us to lay party passion aside, to sign a truce of God over his grave, to seek... some fair means of making a common effort for our common country... Let conference take place before conflict is irrevocably joined."

A Constitutional Conference was established with eight members, four cabinet ministers and four representatives from the Conservative Party. Over the next six months the men met on twenty-one occasions. However, they never came close to an agreement and the last meeting took place in November. George Barnes, the Labour Party MP, called for an immediate creation of left-wing peers. However, when a by-election at Walthamstow suggested a slight swing to the Liberals, Asquith decided to call another General Election.

David Lloyd George called on the British people to vote for a change in the parliamentary system: "How could anyone defend the Constitution in its present form? No country in the world would look at our system - no free country, I mean... France has a Senate, the United States has a Senate, the Colonies have Senates, but they are all chosen either directly or indirectly by the people."

The general election of December, 1910, produced a House of Commons which was almost identical to the one that had been elected in January. The Liberals won 272 seats and the Conservatives 271, but the Labour Party (42) and the Irish (a combined total of 84) ensured the government's survival as long as it proceeded with constitutional reform and Home Rule.

The Parliament Bill, which removed the peers' right to amend or defeat finance bills and reduced their powers from the defeat to the delay of other legislation, was introduced into the House of Commons on 21st February 1911. It completed its passage through the Commons on 15th May. A committee of the House of Lords then amended the bill out of all recognition.

According to Lucy Masterman, the wife of Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP for West Ham North, that David Lloyd George had a secret meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party. Lloyd George had bluffed Balfour into believing that George V had agreed to create enough Liberal supporting peers to pass a new Parliament Bill.

Although a list of 249 candidates for ennoblement, including Thomas Hardy, Bertrand Russell, Gilbert Murray and J. M. Barrie, had been drawn up, they had not yet been presented to the King. After the meeting Balfour told Conservative peers that to prevent the Liberals having a permanent majority in the House of Lords, they must pass the bill. On 10th August 1911, the Parliament Act was passed by 131 votes to 114 in the Lords.

On the day in 1916 Andrée de Jongh, the daughter of a headmaster, was born in Schaerbeek, Belgium. It was a year after the Red Cross matron Edith Cavell had been executed by the Germans for helping some 200 First World War soldiers to escape from Belgium to the neutral Netherlands. According to one report, this story told to her by her father, deeply impressed her.

After leaving college Andrée de Jongh began working as a commercial artist in Malmédy. However, when the German Army invaded on 10th May, 1940 she decided became a nurse in Brussels. Some of her patients were captured British soldiers, whom she helped to send letters home via the Red Cross.

Andrée de Jongh decided to follow the example of her heroine, Edith Cavell, and with the help of her father, Frederic de Jongh, decided to organize an escape line for soldiers and airmen who wished to return to Britain. This included the creation of a series of safe houses in and around Brussels.

The first escape group comprised 11 men were arrested in Spain. General Francisco Franco had a pro-Nazi foreign policy and he prevented the men getting back to Britain. Andrée de Jongh led the next group made up two Belgian soldiers and a British man. This went from Brussels, through France to the Pyrenees, before arriving at the British consulate in Bilbao.

Andrée de Jongh was able to persuade British officials to provide financial and logistical backing for what became known as the Comet Escape Line. Airey Neave, who had himself escaped back to England from Coldiz Prison, was the member of MI9 (the intelligence branch set up to bring home stranded servicemen from occupied territory), was placed in charge of the operation.

Comet worked alongside PAT, an escape line established by Ian Garrow, a soldier in the British Army, who had missed the Dunkirk evacuation and remained in France where he arranged an escape route over the Pyrenees. In October, 1941 Garrow was captured and imprisoned. Albert Guerisse took over at head of the network and when he was arrested, Mary Louise Dissard became the new leader.

Andrée de Jongh became worried that the French Resistance had been penetrated by Gestapo agents and moved her headquarters from Brussels to Paris. Peter Churchill and Odette Sansom were arrested in April, 1943. It is now believed that Henri Déricourt, who had joined the network in January 1943 was responsible for betraying these agents.

On 7th June 1943, René Hardy was arrested by the Gestapo. His chief interrogator, Klaus Barbie, eventually obtained enough information to arrest Jean Moulin, Pierre Brossolette and Charles Delestraint. Moulin and Brossolette both died while being tortured and Delestraint was sent to Dachau where he was killed near the end of the war. Later that month Frederic de Jongh was arrested at Gare du Nord by the Gestapo and was later executed.

This spy network, coordinated by Hugo Bleicher, led to the arrests of several British agents. Andrée de Jongh continued to evade the Gestapo and on one occasion Comet rescued a seven-man RAF bomber crew and got them back to Britain in a week.

Andrée de Jongh remained free until January, 1944. Sent to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp she managed to survive until being liberated in April, 1945. During the Second World War the Comet Line helped return about 800 Allied troops to Britain. Over a hundred of those who helped on the escape route were captured and executed. For her wartime heroism she was awarded the George Medal by the British and the Medal of Freedom by the Americans.

After the war Andrée de Jongh went to the Belgian Congo and worked as a nurse in a leper colony. Later she did similar work in Ethiopia at a leper hospital in Addis Ababa.

Andrée de Jongh, who was created a countess by the King of the Belgians, died at the University Clinic Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, Brussels. on 13th October, 2007.

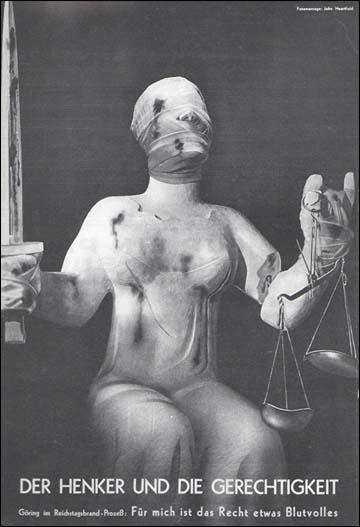

On the day in 1933 John Heartfield publishes Executioner and Justice in protest against the policies of Adolf Hitler. Heartfield was especially upset by the passing of the Enabling Bill. This banned the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party from taking part in future election campaigns. This was followed by Nazi officials being put in charge of all local government in the provinces (7th April), trades unions being abolished, their funds taken and their leaders put in prison (2nd May), and a law passed making the Nazi Party the only legal political party in Germany (14th July).

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)