On this day on 26th December

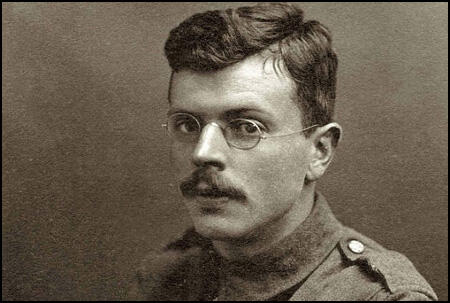

On this day in 1937 Ivor Gurney died of bilateral pulmonary tuberculosis at the City of London Mental Hospital. Gurney, the son of a tailor, was born in Gloucester on 28th August, 1890. Gurney was educated at King's School, Gloucester as a chorister and he won an open scholarship to the Royal College of Music in 1911.

Gurney showed considerable talent as a composer and poet but in May 1913 he was diagnosed as suffering from dyspepsia and was sent home to Gloucester to recuperate. However, it is now accepted that he had a nervous breakdown and was the first sign of bipolar illness.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Gurney volunteered for the Gloucester regiment. He was initially turned down because of his defective eyesight, but as the British Army was short of men, was allowed to join in 1915.

After training at Salisbury he was sent to Riez Bailleul on the Western Front in May 1916. Three months later he was transferred to Albert during the Somme offensive. On 7th April 1917, Gurney was shot in the arm and sent to the army hospital at Rouen. The following month he rejoined his regiment at Arras.

In July 1917 Gurney was transferred to the 184 Machine Gun Company and was moved to Buysscheure and joined the forces preparing for the offensive at Passchendaele. Gurney was gassed at St. Julien on 10th September 1917. He was sent to Edinburgh War Hospital and while recovering a collection of his war poems, Severn and Somme, appeared in November 1917.

After the war Gurney spent time in the Newcastle General Hospital, Lord Derby's War Hospital in Warrington and the Middlesex War Hospital in St. Albans. Gurney was finally discharged from hospital and the army on 4th October 1918.

Gurney's second book of poems, War's Embers was published in May 1919. However he was unable to make a living from his writing and over the next three years worked as a farm labourer, as a pianist in a cinema and as a clerk in the Gloucester Tax Office.

Ivor Gurney suffered from a severe manic depressive illness and after several failed attempts at suicide was sent to a mental asylum in Gloucester. On 28th September 1922, Gurney was certified insane and was transferred to the City of London Mental Hospital at Dartford. He continued to write poetry and his work was published in the London Mercury

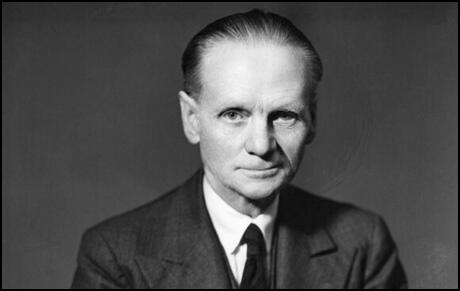

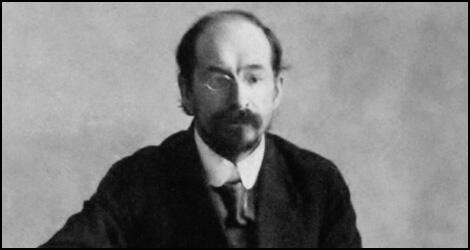

On this day in 1872 Norman Angell was born in Holbeach. At seventeen he emigrated to America but 1898 he moved to Paris where he became manager of the French edition of the Daily Mail. He was made aware of the dangers to world peace by the Moroccan crisis of 1905.

Angell became a pacifist and in his book The Great Illusion (1909), argued that a European war would be economically disadvantageous for victor as well as vanquished. The book had a tremendous impact on the intellectual community and study centres based on the book were established at universities and in industrial centres.

With the financial support of the the industrialist, Sir Richard Garton, and wealthy Quakers such as Joseph Rowntree, Angell established the Garton Foundation. In October 1913 he founded the pacifist journal, War and Peace. Contributors to the journal included Arthur Ponsonby, E. D. Morel and Ramsay MacDonald.

In an attempt to keep Britain out of a European war, Angell formed the Neutrality League. When this failed to achieve its goal, Angell joined Charles Trevelyan, E. D. Morel and Ramsay MacDonald to form the Union of Democratic Control. James Keir Hardie remarked that he was pleased that Angell was involved in this campaign: "I know of no one better fitted to guide the nation right through this dark crisis than he."

In 1920 Norman Angell joined the Labour Party and in 1929 was elected to represent Bradford North in the House of Commons. The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald, the prime minister, was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority voted against the measures suggested by May.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government. MacDonald was determined to continue and his National Government introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet. Labour MPs were furious with what had happened and MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party.

In October, Ramsay MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. This included Norman Angell who was defeated at Bradford North. Angell returned to writing and his book, The Great Illusion: 1933, helped him win the 1933 Nobel prize for peace.

Angell was a great supporter of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War and in 1938 he joined Clement Attlee, William Gallacher, Tom Mann and Stafford Cripps in addressed the returning veterans. Norman Angell died on 7th October 1967.

On this day in 1893 Mao Zedong, the son of a peasant farmer, was born in Chaochan, China. He became a Marxist while working as a library assistant at Peking University and served in the revolutionary army during the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

Inspired by the Russian Revolution the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was established in Shanghai by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in June 1921. Early members included Mao, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De and Lin Biao. Following instructions from the Comintern members also joined the Kuomintang.

Over the next few years Mao, Zhu De and Zhou Enlai adapted the ideas of Lenin who had successfully achieved a revolution in Russia. They argued that in Asia it was important to concentrate on the countryside rather than the towns, in order to create a revolutionary elite.

Mao worked as a Kuomintang political organizer in Shanghai. With the help of advisers from the Soviet Union the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) gradually increased its power in China. Its leader, Sun Yat-sen died on 12th March 1925. Chiang Kai-Shek emerged as the new leader of the Kuomintang. He now carried out a purge that eliminated the communists from the organization. Those communists who survived managed to established the Jiangxi Soviet.

The nationalists now imposed a blockade and Mao Zedong decided to evacuate the area and establish a new stronghold in the north-west of China. In October 1934 Mao, Lin Biao, Zhu De, and some 100,000 men and their dependents headed west through mountainous areas.

The marchers experienced terrible hardships. The most notable passages included the crossing of the suspension bridge over a deep gorge at Luting (May, 1935), travelling over the Tahsueh Shan mountains (August, 1935) and the swampland of Sikang (September, 1935).

The marchers covered about fifty miles a day and reached Shensi on 20th October 1935. It is estimated that only around 30,000 survived the 8,000-mile Long March.

When the Japanese Army invaded the heartland of China in 1937, Chiang Kai-Shek was forced to move his capital from Nanking to Chungking. He lost control of the coastal regions and most of the major cities to Japan. In an effort to beat the Japanese he agreed to collaborate with Mao Zedong and his communist army.

During the Second World War Mao's well-organized guerrilla forces were well led by Zhu De and Lin Biao. As soon as the Japanese surrendered, Communist forces began a war against the Nationalists led by Chaing Kai-Shek. The communists gradually gained control of the country and on 1st October, 1949, Mao announced the establishment of People's Republic of China.

In 1958 Mao announced the Great Leap Forward, an attempt to increase agricultural and industrial production. This reform programme included the establishment of large agricultural communes containing as many as 75,000 people. The communes ran their own collective farms and factories. Each family received a share of the profits and also had a small private plot of land. However, three years of floods and bad harvests severely damaged levels of production. The scheme was also hurt by the decision of the Soviet Union to withdraw its large number of technical experts working in the country. In 1962 Mao's reform programme came to an end and the country resorted to a more traditional form of economic production.

As a result of the failure on the Great Leap Forward, Mao retired from the post of chairman of the People's Republic of China. His place as head of state was taken by Liu Shaoqi. Mao remained important in determining overall policy. In the early 1960s Mao became highly critical of the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. He was for example appalled by the way Nikita Khrushchev backed down over the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Mao became openly involved in politics in 1966 when with Lin Biao he initiated the Cultural Revolution. On 3rd September, 1966, Lin Biao made a speech where he urged pupils in schools and colleges to criticize those party officials who had been influenced by the ideas of Nikita Khrushchev.

Mao was concerned by those party leaders such as Liu Shaoqi, who favoured the introduction of piecework, greater wage differentials and measures that sought to undermine collective farms and factories. In an attempt to dislodge those in power who favoured the Soviet model of communism, Mao galvanized students and young workers as his Red Guards to attack revisionists in the party. Mao told them the revolution was in danger and that they must do all they could to stop the emergence of a privileged class in China. He argued this is what had happened in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev.

Lin Biao compiled some of Mao's writings into the handbook, The Quotations of Chairman Mao, and arranged for a copy of what became known as the Little Red Book, to every Chinese citizen.

Zhou Enlai at first gave his support to the campaign but became concerned when fighting broke out between the Red Guards and the revisionists. In order to achieve peace at the end of 1966 he called for an end to these attacks on party officials. Mao remained in control of the Cultural Revolution and with the support of the army was able to oust the revisionists.

The Cultural Revolution came to an end when Liu Shaoqi resigned from all his posts on 13th October 1968. Lin Biao now became Mao's designated successor.

Mao Zedong now gave his support to the Gang of Four: Jiang Qing (Mao's fourth wife), Wang Hongwen, Yao Wenyuan and Zhange Chungqiao. These four radicals occupied powerful positions in the Politburo after the Tenth Party Congress of 1973. Mao Zedong died in Beijing on 9th September, 1976.

On this day in 1902 women's suffrage campaigner, Susanna Inge, died.

Susanna Inge was born in Folkestone on 3rd February 1820. Her father Richard Inge Austin was a plumber, glazier and painter. A few years later the family moved to London and dropped the surname Austin.

Susanna later wrote: "You not know perhaps, that I never went to school but two months after I was nine years old - that at sixteen I could not write my own name - though I could read well, so I was told, and talk and spell correctly. The teaching I had while in Folkestone, where I had nearly all my schooling was good, and I was very forward, even for my age, being ahead of my cousins even those who were older than me. But writing was not taught in those days while children were so young, thus I knew nothing of writing and my parents were always talking of sending me to writing, but they never did."

In 1836 Susanna bought her a copy book and asked her to write to him. "This I did, though not often, for in those days postage was eight pence a letter and a sheet of paper a penny, so to me, who rarely had more than a penny or time a week to call my own, this was a small fortune and could not often be expended."

The 1841 census returns show that Susanna Inge had returned to Folkestone, where she was working as a family servant in the household of a linen draper in Broad Street. At this time she joined the the London Female Radical Association. When it was founded it stated it wanted to "unite with our sisters in the country, and to use our best endeavours to assist our brethren in obtaining universal suffrage". The organisation made the point that they would use their power as managers of the household to obtain the vote for their men by "to deal as much as possible with those shopkeepers who are favourable to the People's Charter".

Susanna Inge explained her decision in an article for The Northern Star in July, 1842. "As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved". She went on to urge women to “assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also".

In October 1842, Susanna Inge and Mary Ann Walker attempted to establish a Female Chartist Association. Inge argued that in time women should be given the vote. However, she felt before this could happen women "ought to be better educated, and that, if she were, so far as mental capacity, she would in every respect be the equal of man”.

This plan to form a Female Chartist Association was criticised by some male Chartists. One declared that he "did not consider that nature intended women to partake of political rights". He argued that women were "more happy in the peacefulness and usefulness of the domestic hearth, than in coming forth in public and aspiring after political rights".

It was also suggested that if a "young gentleman" might try "to influence her vote through his sway over her affection". Mary Ann Walker responded by claiming that "she would treat with womanly scorn, as a contemptible scoundrel, the man who would dare to influence her vote by any undue and unworthy means; for if he were base enough to mislead her in one way, he would in another.”

On 6th November, 1842, The Sunday Observer reported that Susanna Inge was giving a lecture at the National Charter Hall in London. With her was another woman, Emma Matilda Miles. The newspaper suggested that the women had joined in response to the arrest and punishment of John Frost after the Newport Uprising. It would seem that Inge was a supporter of the Physical Force movement.

Susanna Inge was not content to be a mere propagandist. She had ideas on how Chartism might be better organised. In one letter to the The Northern Star she suggested that every Chartist locality should have its byelaws and plan of organisation hung in a prominent place, that these should be read before every meeting, and that any officer who failed to abide by them should be called to account.

Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force chartists, was not in favour of women having equal political rights with men. He claimed that the role of the woman was to be a "housewife to prepare meals, to wash, to brew, and look after my comforts, and the education of my children." Anna Clark has pointed out that O'Connor demanded "entry into the public sphere for working men" and "the privileges of domesticity for their wives".

Susanna Inge wrote letters to O’Connor's newspaper complaining about his views. These were rejected for publication and in July, 1843, it admitted that Inge "very much questions the propriety or right of Mr O’Connor to name or suggest to the people, through the medium of the Northern Star, any person to fill any office whatever" as "it is not according to her ideas of democracy." The newspaper dismissed her comments with the words: "We dare say Miss Inge is greatly in love with her ideas of democracy; and so she ought, for we fancy they will suit nobody else”

She continued to be active in the Chartist movement and it was reported that Susanna Inge gave a lecture on the subject in August 1843. The Hereford Journal reported that she left the movement in February 1843, after a dispute with Mary Ann Walker. "Miss Susanna Inge, who had hitherto remained silent, now rose and tendered her resignation as secretary of the Female Chartist Association saying, with disdain, that she was quite sick of the business."

Susanna Inge continued to send letters and articles to the The Northern Star. In September, 1844, the editor commented "that even gallantry in Miss Inge’s case is not strong enough to break through" this censorship. She also tried to have her work published in other journals. George Reynolds, the editor of the Reynolds's Miscellany, sent back an article, advising her that she try a better class of magazine “for which its style was more suited”. Another rejection letter suggested "it is very good… it shows you have power to do, but that you require study. This is a proof of what you can do; rather than anything done… This is good but you can do better".

On 18th February 1847, aged 27, she gave birth to a son who she named James. Susanna was unmarried and now took the name Susanna McGregor. In the 1851 census she referred to herself as a widow and was living at 10 Dorrington Street, Clerkenwell. Susanna was recorded as working as a "furrier finisher".

In 1857 Susanna MacGregor and her son emigrated to New York City, settling in Brooklyn, where she found work in the fur trade. She kept in touch with the family of her younger brother John, sending letters, stories and poems to her nieces Alice and Jessie. Attempts to have her work published in American magazines ended in failure.

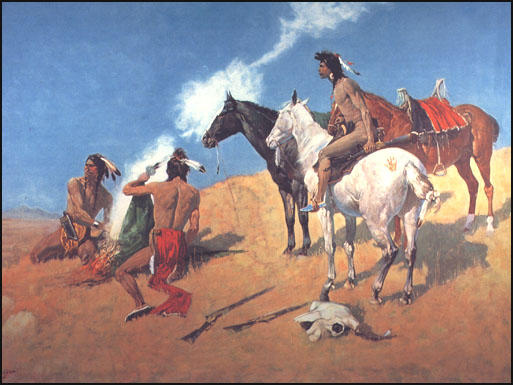

On this day in 1909 Frederic Remington died. Remington was born in New York in 1861. After attending Yale University he became a cowboy and began drawing pictures of the Wild West. He submitted some of these to Harper's Monthly but they were only published after they were re-drawn. Remington's work improved and he was eventually employed as a staff artist.

Remington's illustrations in magazines like Harper's Monthly and Scribner's Magazine made him into a household name. In 1888 Theodore Roosevelt asked him to illustrate Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail. He also provided the art work for Longfellow's The Song of Hiawatha (1891), Pony Tracks (1895) and The Way of an Indian (1906).

For several years Remington also worked as a journalist and provided reports and pictures of major events such as the Indian Wars and the Spanish-American War.

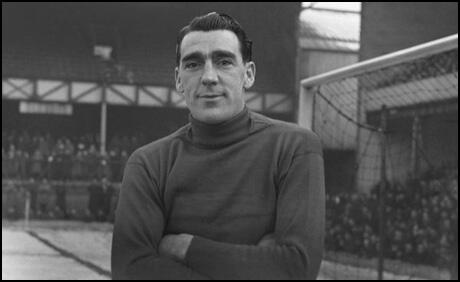

On this day in 1913 Frank Swift was born in Blackpool. A talented goalkeeper he played for Fleetwood City before joining Manchester City in 1932. He made his debut for the club against Derby County on 26th December 1933. City won 2-0 and Swift kept his place in the team.

Swift had a huge finger span of nearly 12 inches which meant he could easily grasp a ball in one hand. He also introduced the long throw out to start an attack rather than the more conventional kick into the opponents half.

In the 1933-34 season Manchester City finished 5th in the First Division of the Football League. The club also enjoyed a good FA Cup run beating Blackburn Rovers (3-1), Hull City (4-1), Sheffield Wednesday (2-0), Stoke City (1-0), Aston Villa (6-1) to reach the final against Portsmouth. On the way to Wembley the goals had been scored by Fred Tilson (7), Alec Herd (4) and Eric Brook (3). The defence, that included players such as Frank Swift, Jackie Bray, Sam Cowan and Matt Busby also performed well.

Manchester City played Portsmouth in the final at Wembley. Fred Tilson had such a terrible injury record that when Sam Cowan introduced him to George VI before the game, he said: "This is Tilson, your Majesty. He's playing today with two broken legs." It was a good job that Tilson did play as he scored both of the goals in the 2-1 victory to increase his total to nine in eight cup games that season. Swift, was so overcome by the achievement that he fainted at the final whistle.

In 1936 Wilf Wild purchased Peter Doherty from Blackpool for a club record fee of £10,000. By the end of 1936 Manchester City had obtained 23 points out of a possible 44. As Gary James points out in Manchester City: The Complete Record: "It was still not Championship form, but enough to give them a foundation to build on.

The New Year saw City climb up the table and, by the time of their meeting with the usual dominant Arsenal in April 1937, the two sides occupied the top two positions." A crowd of 74,918 watched Peter Doherty and Ernie Toseland score the goals that gave City a 2-0 victory.

Over the next three weeks Manchester City went on to beat Sunderland (3-1), Preston North End (5-2) and Sheffield Wednesday (4-1). City could only draw their last game 2-2 but by this time had been crowned champions. City scored 107 goals in the 1936-37 season, the main contributors being Peter Doherty (30), Eric Brook (20), Alec Herd (17), Fred Tilson (15) and Ernie Toseland (7). The defence, that included Frank Swift, Jackie Bray, Billy Dale and Sam Barkas, also did well that season, only letting in 61 goals in 42 games. Swift played in all 42 games that season.

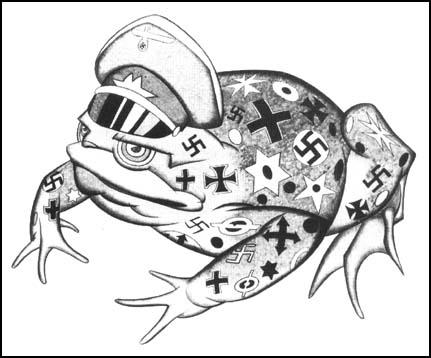

It was the first time that Manchester City had won the First Division league title. The club celebrated by going on a tour of Nazi Germany. Over 70,000 turned up to the Berlin Olympic Stadium to watch City play a team made up of Germany's best players. Adolf Hitler wanted to make use of this game as propaganda for his Nazi government and the City players were asked to to give the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. Peter Doherty later recalled: "We were expected to give the Nazi salute at the line-up before the match started; but we decided merely to stand to attention. When the German national anthem was played, only 11 arms went up instead of the expected 22!" City lost the game 3-2 after a uncharacteristic mistake by Frank Swift.

In the 1937-38 season Manchester City once again scored more goals than any other club in the First Division. Once again Peter Doherty (23), Eric Brook (16) and Alec Herd (12) were the leading scorers. However the defence, performed badly letting in 77 goals. The club finished in 21st position and was relegated to the Second Division.

Swift's football career was interrupted by the Second World War. During the conflict he became a special constable. By the time the Football League started again after the war he was 33 years old and past his best. However, he retained his place in the team and was a member of the side that won the Second Division championship under manager Sam Cowan in the 1946-47 season.

Swift won his first international cap for England against Northern Ireland on 28th September 1946. England won the game 7-2 and held his place for the next three years. On 16th May 1948, Swift was chosen to captain England against Italy. Swift therefore became the first goalkeeper since 1873 to captain the national team.

After winning 14 caps Swift decided to retire from professional football in order to take up a career in journalism by joining the staff of the News of the World.

Frank Swift died on 6th February 1958 in the Munich Air Disaster after reporting on Manchester United's European Cup match against Red Star Belgrade.

On this day in 1933 Anatoly Lunacharsky died.Lunacharsky, the son of a local government official, was born in Poltava, Ukraine, in 1875. When he was fifteen he joined an illegal Marxist study-circle in Kiev.

Lunacharsky was aware of the lack of academic freedom in Russia so he decided to study social sciences at Zurich University. while there he developed a close friendship with Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches who had also been converted to Marxism.

In 1896 Lunacharsky returned to Russia and joined the illegal Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) but was soon arrested by Okhrana. Lunacharsky was sentenced to internal exile in Siberia where he met Alexander Bogdanov, who later became his brother-in-law.

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Vladimir Lenin and Julius Martov, two of SDLP's leaders. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists.

Julius Martov based his ideas on the socialist parties that existed in other European countries such as the British Labour Party. Lenin argued that the situation was different in Russia as it was illegal to form socialist political parties under the Tsar's autocratic government. At the end of the debate Martov won the vote 28-23 . Vladimir Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks.

Lunacharsky joined the Bolsheviks and with Alexander Bogdanov co-edited a party journal in Switzerland. He also wrote an important books on Marxist philosophy, An Essay in Positive Aesthetics and Religion and Socialism. Lunacharsky also worked with Vladimir Lenin publishing Vpered and Proletarri and smuggling copies into Russia.

Lunacharsky returned to Russian during the 1905 Revolution and co-edited the journal, Zovaya Zhizn with Maxim Gorky, the first Bolsheviks newspaper to be published legally in Russia.

When Vladimir Lenin attacked Lunacharsky for having deviant Marxist views, he left and joined the Mensheviks. In August, 1914, he began co-edited the anti-war newspaper, Our World, with Julius Martov and Leon Trotsky. when the paper was banned by the authorites Lunacharsky moved to Switzerland.

After the February Revolution Lunacharsky returned to Russia and along with Leon Trotsky joined the Bolsheviks in August, 1917. An impressive orator, Lunacharsky played an important role in persuading the industrial workers of Petrograd to support the October Revolution.

In November, 1917, Vladimir Lenin appointed Lunacharsky as the government's Commissar for Education and Enlightenment. He tried to completely reform Russian education system. He also introduced a system for subsidizing the arts. Another inovation was Workers' Faculties that provided intensive and accelerated courses to train technicians and administrators from the working classes and the peasantry.

Lunacharsky was also responsible for the Soviet Government's campaign against adult illiteracy. In 1917 over 65 per cent of the adult population were illiterate but by the time Lunacharsky left office it was virtually zero.

In 1930 Lunacharsky and Maxim Litvinov represented the Soviet Union at the League of Nations in Geneva. Joseph Stalin appointed him ambassador to Spain but he died before he could take up his post.

On this day in 1960 Robert Sherriffs died. Sherriffs was born in Arbroath on 13th February on 13th February 1906. After studying at the Edinburgh College of Arts he began having his cartoons published in The Bystander, The Strand Magazine and The Sketch. In 1934 he drew a weekly cartoon for the Radio Times. In 1944 he published the comic novel, Salute If You Must.

After the Second World War Sherriffs was expected to become staff cartoonist on the Daily Herald but this went to his friend, George Whitelaw, instead. In 1948 he succeeded James Dowd as film caricaturist on Punch Magazine. He claimed "I regarded caricatures as designs and the expressions on faces merely as changes in a basic pattern."

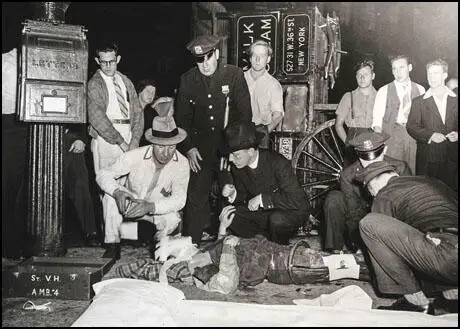

On this day in 1968 Arthur Fellig (Weegee) died. Fellig was born in Zloczew, Poland, in 1899. When Fellig was eleven his family moved to the United States and they settled in New York City. Arthur's father worked as a pushcart vendor and a janitor in a tenement building.

Fellig left school at fourteen to help support his family. His first job was as an assistant to a commercial photographer. He also obtained extra money by taking street portraits.

In 1918 Fellig was employed as a darkroom technician by Ducket & Adler in Lower Manhattan. This is followed by similar work with Acme Newspictures (later absorbed by United Press International Photos).

In 1935 Fellig left his job as a darkroom technician and attempted to make a living as a freelance photographer. By monitoring police and fire-department radio calls Fellig was able to obtain a large number of dramatic photographs. The ability to be the first photographer on the scene of a major incident, resulted in him being given the nickname, Weegee (a reference to the fortune-teller's Ouija board).

Fellig's photographs appeared in nearly all of New York's newspapers including New York Tribune, New York Post, PM, New York Journal-American and the New York Sun. In 1941 the Photo League put on an exhibition of his work, Weegee: Murder is My Business.

After the publication of his highly successful book, Naked City (1945). Fellig abandoned crime photos and concentrated on advertising assignments for Life, Vogue, Look and Fortune. Other books by Fellig included Weegee People (1946), Naked Hollywood (1953) and Weegee by Weegee (1961). Arthur Fellig died on 26th December, 1968.