On this day on 20th April

On this day in 1534 Elizabeth Barton is executed on the orders of Henry VIII. On the scaffold she told the assembled crowd: "I have not only been the cause of my own death, which most justly I have deserved, but also I am the cause of the death of all these persons which at this time here suffer. And yet, to say the truth, I am not so much to be blamed considering it was well known unto these learned men that I was a poor wench without learning - and therefore they might have easily perceived that the things that were done by me could not proceed in no such sort, but their capacities and learning could right well judge from whence they proceeded... But because the things which I feigned was profitable unto them, therefore they much praised me... and that it was the Holy Ghost and not I that did them. And then I, being puffed up with their praises, feel into a certain pride and foolish fantasy with myself."

Elizabeth Barton was born in about 1506. Very little is known about her early life or family. Barton is unlikely to have received any sort of formal education during her childhood, and she was almost certainly illiterate. In 1525 she was a servant in the household of a certain Thomas Cobb, farm manager to Archbishop William Warham, at Goldwell House in the village of Aldington, some 20 miles from Canterbury.

Barton began to suffer from an unknown ailment. Edward Thwaites reported that in 1525 she became seriously ill: "It happened a certain maiden named Elizabeth Barton... to be touched with a great infirmity in her body, which did ascend at diverse times up into her throat, and swelled greatly, during the time whereof she seemed to be in grievous pain, in so much as a man would have thought that she had suffered the pangs of death itself, until the disease descended and fell down into the body again."

According to Barton's biographer, Diane Watt: "In the course of this period of sickness and delirium she began to demonstrate supernatural abilities, predicting the death of a child being nursed in a neighbouring bed. In the following weeks and months the condition from which she suffered, which may have been a form of epilepsy, manifested itself in seizures (both her body and her face became contorted), alternating with periods of paralysis. During her death-like trances she made various pronouncements on matters of religion, such as the seven deadly sins, the ten commandments, and the nature of heaven, hell, and purgatory. She spoke about the importance of the mass, pilgrimage, confession to priests, and prayer to the Virgin and the saints."

In 1526 she entered St Sepulchre's Nunnery. Elizabeth had meetings with Edward Bocking, a monk at Christchurch Priory. According to Barton's biographer, Edward Thwaites, "Elizabeth Barton advanced, from the condition of a base servant to the estate of a glorious nun." Thwaites claimed a crowd of about 3,000 people attended one of the meetings where she told of her visions. Other sources say it was 2,000 people. Sharon L. Jansen points out: "In either case there was a sizable gathering at the chapel, indicating something of how quickly and widely reports of her visions had spread."

Bishop Thomas Cranmer was one of those who saw Barton. He wrote a letter to Hugh Jenkyns explaining that he had seen "a great miracle" that had been created by God: "Her trance lasted... the space of three hours and more... Her face was wonderfully disfigured, her tongue hanging out... her eyes were... in a manner plucked out and laid upon her cheeks... a voice was heard... speaking within her belly, as it had been in a cask... her lips not greatly moving.... When her belly spoke about the joys of heaven... it was in a voice... so sweetly and so heavenly that every man was ravished with the hearing thereof... When she spoke of hell... it put the hearers in great fear."

Gradually she began to experience revelations of a controversial character. Elizabeth, now known as the Nun of Kent, was taken to see Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher. On 1st October 1528, Warham wrote to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey recommending her as "a very well-disposed and virtuous woman". He told of how "she had revelations and special knowledge from God in certain things concerning my Lord Cardinal (Wolsey) and also the King's Highness".

Archbishop Warham arranged a meeting between Elizabeth Barton to see Cardinal Wolsey. She told him that she had seen a vision of him with three swords - one representing his power as Legate (the representative of the Pope), the second his power as Lord Chancellor, and the third his power to grant Henry VIII a divorce from Catherine of Aragon.

Wolsey arranged for Elizabeth Barton to see the King. She told him to burn English translations of the Bible and to remain loyal to the Pope. Elizabeth then warned the King that if he married Anne Boleyn he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. He was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer commented later that Henry put off his marriage to Anne because "of her visions". William Tyndale was less convinced by her trances and claimed that her visions were either feigned or the work of the devil.

It is claimed that Edward Bocking encouraged her to speak out against religious reformers inspired by the writings of Martin Luther. "Bocking... is said to have induced her to declare herself an inspired emissary for the overthrow of Protestantism and the prevention of the divorce of Queen Catherine.... There is little doubt that he was her chief instigator in the continuance of her career of deception. His share in the affair, though it cannot be excused, must be ascribed to a mistaken zeal for the preservation of the ancient Faith."

However, Bocking's biographer, Ethan H. Shagan, has claimed that his role in this is not conclusive. "Barton... turned to politics, agitating against Henry VIII's plan to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and from the beginning of these activities Bocking was her closest confidant. His most important role, however, was as a publicist for Barton. He was often accused, both by Henry VIII's government and by later historians, of having concocted rather than merely disseminated her revelations. It is impossible to tell whether there is substance in the charge but it has the appearance of misogyny, and certainly the government benefited greatly by using it to undermine the commonplace assumption that Barton's revelations must have been holy because a woman could not normally have had the wits to invent them on her own."

Gertrude Courtenay, Marchioness of Exeter, travelled from her house in Kew to Canterbury, in disguise, to consult with Barton. As Sharon L. Jansen, the author of Dangerous Talk and Strange Behaviour: Women and Popular Resistance to the Reforms of Henry VIII (1996) has pointed out: "The Courtenays, along with the Nevilles and the Poles, were the last Yorkist claimants to the English throne; the contact between Gertrude Courtenay and Elizabeth Barton was thus dangerous to both of them."

Father Hugh Rich, a Observant Friar of Richmond, a passionate supporter of Catherine of Aragon, encouraged her to meet Elizabeth Barton. However, she sensibly refused as she feared she would be accused of being involved in a conspiracy against the King. Alison Weir has argued that Barton was "fortunate that for the time being the authorities were prepared to dismiss her as a harmless lunatic; nor did they molest her when she persisted in repeating her prophecies and threats."

Elizabeth Barton travelled the country speaking to large groups of people. As her reputation grew people travelled to St Sepulchre's Nunnery to "consult her about their lives and sins, to ask her to discern spirits, or to seek her intercession for the sick, the dying, and the dead". Barton also told the people that God approved of pilgrimages and the practice of Mass. In other words, she claimed that God supported those things that were being attacked by religious reformers such as Martin Luther.

In October 1532 Henry VIII agreed to meet Elizabeth Barton again. According to the official record of this meeting: "She (Elizabeth Barton) had knowledge by revelation from God that God was highly displeased with our said Sovereign Lord (Henry VIII)... and in case he desisted not from his proceedings in the said divorce and separation but pursued the same and married again, that then within one month after such marriage he should no longer be king of this realm, and in the reputation of Almighty God should not be king one day nor one hour, and that he should die a villain's death."

Soon afterwards the King discovered that Anne Boleyn was pregnant. As it was important that the child should not be classed as illegitimate, arrangements were made for Henry and Anne to get married. King Charles V of Spain threatened to invade England if the marriage took place, but Henry ignored his threats and the marriage went ahead on 25th January, 1533. It was very important to Henry that his wife should give birth to a male child. Without a son to take over from him when he died, Henry feared that the Tudor family would lose control of England.

Sir Thomas More was careful to make it clear that despite his growing opposition to the King's church policies, he accepted Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn as being part of God's providence, and would neither "murmur at it nor dispute upon it", since "this noble woman" was "royally anointed queen". In the summer of 1533 Thomas More met Elizabeth Barton. Soon afterwards he wrote to her warning about the dangers she faced if she continued to speak with "lay persons, of any such manner things as pertain to princes' affairs, or the state of the realm... with any person, high and low, of such manner things as may to the soul be profitable for you to show and for them to know".

During this period Edward Bocking produced a book detailing Barton's revelations. In 1533 a copy of Bocking's manuscript was made by Thomas Laurence of Canterbury, and 700 copies of the book were issued by the printer John Skot, who supplied 500 copies to Bocking. Thomas Cromwell discovered what was happening and ordered that all copies were seized and destroyed. This operation was successful and no copies of the book exists today.

In the summer of 1533 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer wrote to the prioress of St Sepulchre's Nunnery asking her to bring Elizabeth Barton to his manor at Otford. On 11th August she was questioned, but was released without charge. Thomas Cromwell then questioned her and, towards the end of September, Edward Bocking was arrested and his premises were searched. Bocking was accused of writing a book about Barton's predictions and having 500 copies published. Father Hugh Rich was also taken into custody. In early November, following a full scale investigation, Barton was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Elizabeth Barton was examined by Thomas Cromwell, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Hugh Latimer. During this period she had one final vision "in which God willed her, by his heavenly messenger, that she should say that she never had revelation of God". In December 1533, Cranmer reported "she confessed all, and uttered the very truth, which is this: that she never had visions in all her life, but all that ever she said was feigned of her own imagination, only to satisfy the minds of them the which resorted unto her, and to obtain worldly praise."

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has suggested that Barton had been tortured: "It may be that she was put on the rack. In any case it was declared that she had confessed that all her visions and revelations had been impostures... It was then determined that the nun should be taken throughout the kingdom, and that she should in various places confess her fraudulence." Barton secretly sent messages to her adherents that she had retracted only at the command of God, but when she was made to recant publicly, her supporters quickly began to lose faith in her.

Eustace Chapuys, reported to King Charles V on 12th November, 1533, on the trial of Elizabeth Barton: "The king has assembled the principal judges and many prelates and nobles, who have been employed three days, from morning to night, to consult on the crimes and superstitions of the nun and her adherents; and at the end of this long consultation, which the world imagines is for a more important matter, the chancellor, at a public audience, where were people from almost all the counties of this kingdom, made an oration how that all the people of this kingdom were greatly obliged to God, who by His divine goodness had brought to light the damnable abuses and great wickedness of the said nun and of her accomplices, whom for the most part he would not name, who had wickedly conspired against God and religion, and indirectly against the king."

A temporary platform and public seating was erected at St. Paul's Cross and on 23rd November, 1533, Elizabeth Barton made a full confession in front of a crowd of over 2,000 people. "I, Dame Elizabeth Barton, do confess that I, most miserable and wretched person, have been the original of all this mischief, and by my falsehood have grievously deceived all these persons here and many more, whereby I have most grievously offended Almighty God and my most noble sovereign, the King's Grace. Wherefore I humbly, and with heart most sorrowful, desire you to pray to Almighty God for my miserable sins and, ye that may do me good, to make supplication to my most noble sovereign for me for his gracious mercy and pardon."

Over the next few weeks Elizabeth Barton repeated the confession in all the major towns in England. It was reported that Henry VIII did this because he feared that Barton's visions had the potential to cause the public to rebel against his rule: "She... will be taken through all the towns in the kingdom to make a similar representation, in order to efface the general impression of the nun's sanctity, because this people is peculiarly credulous and is easily moved to insurrection by prophecies, and in its present disposition is glad to hear any to the king's disadvantage."

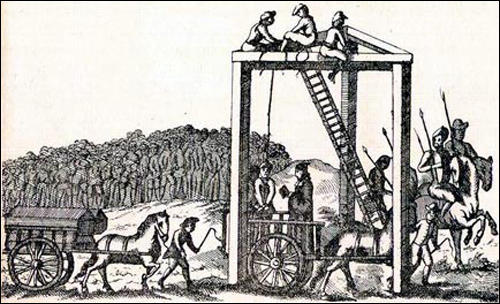

Parliament opened on 15th January 1534. A bill of attainder charging Elizabeth Barton, Edward Bocking, Henry Risby (warden of Greyfriars, Canterbury), Hugh Rich (warden of Richmond Priory), Henry Gold (parson of St Mary Aldermary) and two laymen, Edward Thwaites and Thomas Gold, with high treason, was introduced into the House of Lords on 21st February. It was passed and then passed by the House of Commons on 17th March. (29) They were all found guilty and sentenced to be executed on 20th April, 1534. They were "dragged through the streets from the Tower to Tyburn".

On this day in 1889 Adolf Hitler was born in the small Austrian town of Braunau near the German border. Both Hitler's parents had come from poor peasant families. His father Alois Hitler, the illegitimate son of a housemaid, was an intelligent and ambitious man and was at the time of Adolf Hitler's birth, a senior customs official in Lower Austria.

Alois had been married before. In 1873 he had married Anna Glasl, the fifty-year-old adopted daughter of another customs collector. According to Ian Kershaw, the author of Hitler 1889-1936 (1998): "It is unlikely to have been a love-match. The marriage to a woman fourteen years older than himself had almost certainly a material motive, since Anna was relatively well off, and in addition had connections within the civil service." Anna suffered from poor health and her age meant that she was unable to have children.

Klara Polzl, Adolf Hitler's mother, left home at sixteen to join the household of her second cousin, Alois Hitler. Soon afterwards Alois began a sexual relationship with another maid in the house, Franziska Matzelberger. In 1877 Alois changed his surname from Schickelgruber to Hitler. It is claimed he did this to inherit money from Johann Nepomuk Hiedler (Hitler was an another way of spelling Hiedler - both mean "smallholding" in German.

Franziska saw Klara as a potential rival and insisted that she left the household. In 1882 Franziska gave birth to a child named Alois. When Anna Hitler died in 1883, Alois married Franziska and two months after the wedding she gave birth to a second child, Angela. Franziska developed tuberculosis and Alois invited Klara to return to the home to look after his two young children. Franziska, aged twenty-three, died in August, 1884. Alois also began a sexual relationship with Klara and on 7th January, 1885, the couple married. As they were second cousins they had to apply for episcopal dispensation to permit the marriage.

The first of the children of Alois's third marriage, Gustav, was born in May 1885, to be followed in September the following year by a second child, Ida, and another son, Otto, who died only days after his birth. In December 1887 both Gustav and Ida contracted diphtheria and died within weeks of each other. On 20th April 1889, Klara gave birth to her fourth child, Adolf. Edmund was born in 1894 but lived only six years. The fifth and last child, Paula, was born in 1896.

In 1895, when Adolf Hitler was six years old, his father, Alois Hitler retired from government service. For the next four years he moved restlessly from one district to another near Linz, buying and selling farms, raising bees, and spent most of his time drinking in local inns. According to Adolf: "When finally, at the age of fifty-six, he went into retirement, he could not bear to spend a single day of his leisure in idleness. Near the Upper Austrian market village of Lambach he bought a farm, which he worked himself, and thus, in the circuit of a long and industrious life, returned to the origins of his forefathers. It was at this time that the first ideals took shape in my breast. All my playing about in the open, the long walk to school, and particularly my association with extremely husky boys, which sometimes caused my mother bitter anguish, made me the very opposite of a stay-at-home. And though at that time I scarcely had any serious ideas as to the profession I should one day pursue, my sympathies were in any case not in the direction of my father's career."

Alois was an authoritarian, overbearing, domineering husband and a stern, distant, aggressive and violent father. Konrad Heiden commented: "Hitler's father was a short-tempered old man, grown prematurely inactive. He had fought a bitter struggle with life, had made the hardest sacrifices, and in the end things had not gone according to his will. He goes walking about... usually holding his gold-bordered velvet cap in his hands, looks after his bees, leans against the fence, chats rather laconically with his neighbours. He looks on as a friend erects a little saw-mill and sourly remarks: such are the times, the little fellows are coming up, the big ones going down. His lungs are affected, he coughs and occasionally spits blood."

Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "Hitler's mother was a quiet, hardworking woman with a solemn, pale face and large, staring eyes. She kept a clean household and labored diligently to please her husband. Hitler loved his indulgent mother, and she in turn considered him her favorite child, even if, as she said, he was moonstruck. Later, he spoke of himself as his mother's darling. She told him how different he was from other children. Despite her love, however, he developed into a discontented and resentful child. Psychologically, she unconsciously made him, and through him the world would pay for her own unhappiness with her husband. Adolf feared his strict father, a hard and difficult man who set the pattern for the youngster's own brutal view of life... This sour, hot-tempered man was master inside his home, where he made the children feel the lash of his cane, switch, and belt. Alois snarled at his son, humiliated him, and corrected him again and again. There was deep tension between two unbending wills. It is probable that Adolf Hitler's later fierce hatreds came in part from this hostility to his father. He learned early in life that right was always on the side of the stronger one."

Alois Hitler was extremely keen for his son to do well in life. Alois did have another son Alois Matzelsberger, but he had been a big disappointment to him and eventually ended up in prison for theft. Alois was a strict father and savagely beat his son if he did not do as he was told. Hitler later wrote: "After reading one day in Karl May (a popular writer of boys' books) that the brave man gives no sign of being in pain, I made up my mind not to let out any sound next time I was beaten. And when the moment came - I counted every blow." Afterwards he proudly told his mother: "Father hit me thirty-two times.... and I did not cry". Hitler told Christa Schroeder about his relationship with his parents: "I never loved my father, but feared him. He was prone to rages and would resort to violence. My poor mother would then always be afraid for me."

In early childhood Adolf Hitler was often ill and his mother became over-protective, wanting nothing less than to lose another child. Dr. Edward Bloch, her Jewish doctor, remarked: "Outwardly, his love for his mother was his most striking feature... I have never seen a closer attachment between mother and son." Hitler was deeply fond of his mother. He said that one of his happiest memories was of sleeping alone with her in the big bed when his father was away.

Adolf Hitler also found it very distressing to see his mother suffering from "drunken beatings". His sister, Paula, said her mother was "a very soft and tender person, the compensatory element between the almost too harsh father and the very lively children who were perhaps somewhat difficult to train. If there were ever quarrels or differences of opinion between my parents it was always on account of the children. It was especially my brother Adolf who challenged my father to extreme harshness and who got his sound thrashings every day. How often on the other hand did my mother caress him and try to obtain with her kindness what her father could not succeed in obtaining with his harshness!"

Adolf Hitler did extremely well at primary school and it appeared he had a bright academic future in front of him. Hitler later referred to "this happy time" when "school work was ridiculously easy, leaving me so much free time that the sun saw more of me than my room". He was also popular with other pupils and was much admired for his leadership qualities. His religious mother sent him to the monastery school at Lambach, where she hoped that he would eventually become a monk. He was expelled after he was caught smoking on the monastery grounds.

Hitler began his secondary schooling on 17th September, 1900. The attention he had received from his village teacher was now replaced by the more impersonal treatment of a number of teachers responsible for individual subjects. Competition was much tougher in the larger secondary school and his reaction to not being top of the class was to stop trying. His father was furious as he had high hopes that Hitler would follow his example and join the Austrian civil service when he left school. However, Hitler was a stubborn child and attempts by his parents and teachers to change his attitude towards his studies were unsuccessful.

Adolf Hitler also lost his popularity with his fellow pupils. They were no longer willing to accept him as one of their leaders. As Hitler liked giving orders he spent his time with younger pupils. He enjoyed games that involved fighting and he loved re-enacting battles from the Boer War. His favourite game was playing the role of a commando rescuing Boers from English concentration camps. However, his favourite game was taking shots at rats with an airgun.

Hitler had little respect for his teachers: "Most of my teachers had something wrong with them mentally, and quite a few of them ended their days as honest-to-God lunatics." He later recalled: "They had no sympathy with youth; their one object was to stuff our brains and turn us into erudite apes like themselves. If any pupil showed the slightest trace of originality, they persecuted him relentlessly, and the only model pupils whom I have ever known have all been failures in later-life."

Dr. Eduard Humer was not very impressed with Hitler as a student. He recorded in 1923: "I can recall the gaunt, pale-faced youth pretty well. He had definite talent, though in a narrow field. But he lacked self-discipline, being notoriously cantankerous, wilful, arrogant, and bad-tempered. He had obvious difficulty in fitting in at school. Moreover he was lazy... his enthusiasm for hard work evaporated all too quickly. He reacted with ill-concealed hostility to advice or reproof; at the same time, he demanded of his fellow pupils their unqualified subservience, fancying himself in the role of leader."

Konrad Heiden was a journalist working in Munich who was one of the first people to investigate Hitler's early life. He discovered that several people he interviewed mentioned Hitler's laziness: "If we look into his laziness, it seems to have concealed fear of his fellow men; he feared their judgment, and hence shunned doing anything which he would have had to submit to their judgment. Perhaps his childhood furnishes an explanation. The data at our disposal show Adolf Hitler to be a model case for psychoanalysis, one of whose main theories is that every man wants to murder his father and marry his mother. Adolf Hitler hated his father, and not only in his subconscious; by his insidious rebelliousness he may have brought him to his grave a few years before his time; he loved his mother deeply, and himself said that he had been a mother's darling. Constantly humiliated and corrected by his father, receiving no protection against the mistreatment of outsiders, never recognized or appreciated, driven into a lurking silence - thus, as a child, early sharpened by hard treatment, he seems to have grown accustomed to the idea that right is always on the side of the stronger; a dismal conviction from which people often suffer who as children did not find justice in the father who should have been the natural source of justice. It is a conviction for all those who love themselves too much and easily forgive themselves every weakness; never are their own incompetence and laziness responsible for failures, but always the injustice of the others."

The only teacher Adolf Hitler appeared to like at secondary school was Leopold Potsch, his history master. Potsch, like many people living in Upper Austria, was a German Nationalist. Potsch told Hitler and his fellow pupils of the German victories over France in 1870 and 1871 and attacked the Austrians for not becoming involved in these triumphs. Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German Empire, was one of Hitler's early historical heroes.

Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf (1925): "Dr. Leopold Potsch, my professor at the Realschule in Linz, embodied this requirement to an ideal degree. This old gentleman's manner was as kind as it was determined, his dazzling eloquence not only held us spellbound but actually carried us away. Even today I think back with gentle emotion on this gray-haired man who, by the fire of his narratives, sometimes made us forget the present; who, as if by enchantment, carried us into past times and, out of the millennial veils of mist, molded dry historical memories into living reality. On such occasions we sat there, often aflame with enthusiasm, and sometimes even moved to tears. What made our good fortune all the greater was that this teacher knew how to illuminate the past by examples from the present, and how from the past to draw inferences for the present. As a result he had more understanding than anyone else for all the daily problems which then held us breathless. He used our budding nationalistic fanaticism as a means of educating us, frequently appealing to our sense of national honor. By this alone he was able to discipline us little ruffians more easily than would have been possible by any other means. This teacher made history my favorite subject. And indeed, though he had no such intention, it was then that I became a little revolutionary. For who could have studied German history under such a teacher without becoming an enemy of the state which, through its ruling house, exerted so disastrous an influence on the destinies of the nation? And who could retain his loyalty to a dynasty which in past and present betrayed the needs of the German people again and again for shameless private advantage?"

On this day in 1937 Agnes Hodgson writes about nursing men in the International Brigades. "Another busy day. A German's leg amputated during the night, and a number from the Battalion of Death (Anarchists) with minor wounds from Tardienta in the a.m. The German had been seven days without food, and his leg was alive with maggots as he had been lying among the fascist wounded. We have had about a dozen fascist wounded prisoners here, treated exactly as other patients, to their astonishment. Also officials who interviewed them questioned them politely. Later in the day a fair number of wounded were brought in from the Carlos Marx battalion. A lung case and one with 11 perforations in the abdomen were admitted to the ward. A very busy day. The Political Commissar, on the eighth day after his perforated stomach, began vomiting and haemorrhaging. A very bad patient, possibly his own fault, as he drank water from the ice bag. He has been given blood transfusions and all manner of things but he will probably die. It is a hard job getting used to the ward in these conditions. Two hernia operations were done today as well."

Una Wilson on board ship in Sydney in October 1936.

On this day in 1941 Marmaduke Pattle, RAF's leading war ace, is killed.Pattle, the son of English parents, was born in Butterworth, South Africa, on 3rd July, 1914. After leaving school he joined the South African Air Force (SAAF) as a cadet.

In 1936 Pattle moved to England where he joined the Royal Air Force. A member of 80 Squadron he was sent to Egypt two years later to take command of B Flight.

Flight Commander Pattle first saw action in the Second World War on 4th August 1940 over Libya when he shot down two Italian aircraft. He was also downed and it took him two days to walk back to the Egyptian border. Over the next few months Pattle obtained twenty victories during the Desert War.

In November 1940 Pattle was sent to Greece where he took command of 33 Squadron. On 6th April, 1941, the German Army invaded Greece. Pattle and his pilots now had the problem of dealing with the Luftwaffe.

On Sunday 20th April, Pattle led his men against a large formation of Messerschmitt 110 over Eleusis Bay, near Athens. Heavily outnumbered, Pattle was killed while going to the aid of a colleague in difficulties. By the time of his death Marmaduke Pattle had fifty victories making him the RAF's top-scoring pilots of the war

On this day in 1945 Adolf Hitler makes his last trip to the surface to award Iron Crosses to boy soldiers of the Hitler Youth. At the beginning of 1945 the Soviet troops entered Nazi Germany. On 16th January, Hitler moved into the Führerbunker in Berlin. He was joined by Eva Braun, Gretl Braun, Joseph Goebbels, Magda Goebbels, Hermann Fegelein, Rochus Misch, Martin Bormann, Arthur Bormann, Walter Hewell, Julius Schaub, Erich Kempka, Heinz Linge, Julius Schreck, Ernst-Gunther Schenck, Otto Günsche, Traudl Junge, Christa Schroeder and Johanna Wolf.

Hitler was now nearly fifty-five years old but looked much older. His hair had gone grey, his body was stooped, and he had difficulty in walking. His voice had become feeble and his eyesight was so poor that that he needed special lenses even to read documents from his "Führer typewriter". Hitler also developed a tremor in his left arm and leg. He had originally suffered from this during the First World War and also after the failure of the Munich Putsch in 1923. It was a nervous disorder that reappeared whenever Hitler felt he was in danger.

People who had not seen him for a few months were shocked by his appearance. One man remarked: "It was a ghastly physical image he presented. The upper part of his body was bowed and he dragged his feet as he made his way slowly and laboriously through the bunker from his living room... If anyone happened to stop him during this short walk (some fifty or sixty yards), he was forced either to sit down on one of the seats placed along the walls for the purpose, or to catch hold of the person he was speaking to... Often saliva would dribble from the comers of his mouth... presenting a hideous and pitiful spectacle."

Hitler talked of the possibility that Britain and the United States would go to war with the Soviet Union and that Germany would be saved. He told one of his generals that "throughout history coalitions have always gone to pieces sooner or later." Hitler was right that the Soviet Union and the United States would eventually be in conflict, but unfortunately for him this did not happen until after the war had ended.

The situation became so desperate that on 22nd April, Hitler sent Christa Schroeder, Johanna Wolf, Arthur Bormann, Dr. Theodor Morell, Admiral Karl-Jesco von Puttkamer and Dr. Hugo Blaschke, away. Schroeder later recalled: "He received us in his room looking tired, pale and listless. "Over the last four days the situation has changed to such an extent that I find myself forced to disperse my staff. As you are the longest serving, you will go first. In an hour a car leaves for Munich."

On this day in 1975 John Vachon died in New York. John Vachon was born in St-Paul, Minnesota, on 19th May 1914. After graduating from Cretin High School he studied at the University of St. Thomas. He graduated in 1934 and managed to find work as a filing clerk for the Farm Security Administration.

In 1936 Roy Stryker recruited him to join a small group of photographers working for the FSA. This group included Esther Bubley, Marjory Collins, Mary Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, Arthur Rothstein, Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Gordon Parks, Charlotte Brooks, Carl Mydans, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn. These photographers were employed to publicize the conditions of the rural poor in America.

During the Second World War he worked as a photographer for the Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. (1942-1943). He was also employed by the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.

In 1947 Vachon became a staff photographer for Life Magazine. This was followed by employment with Look Magazine (1949-1971). After the closure of this magazine he became a freelance photographer and a visiting lecturer at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

On this day in 1982 Archibald MacLeish died in Boston. Archibald MacLeish was born in Glencoe, Illinois, on 7th May 1892. After graduating from Yale University in 1915 and two years later his first book of poems, Tower of Ivory, was published.

MacLeish he joined the United States Army in 1917. He served in France as a field artillery officer during the First World War and during the summer of 1918 took part in the2nd Battle of the Marne. On his return to the United States MacLeish resumed his studies and received a law degree from Harvard Law School in 1919 and became a lawyer in Boston.

In 1923 MacLeish gave up his legal career and decided to tour Europe. During this period he published several books of poetry including The Happy Marriage (1924), The Pot of Earth (1925), Streets in the Moon (1926), The Hamlet of A. MacLeish (1928) and New Found Land(1930). He also wrote two plays, Nobodaddy and Panic which dealt with the Wall Street Crash.

MacLeish worked as editor of Fortune Magazine (1929-1938) but continued to write poetry.Conquistador (1932) won the Pulitzer Prize and His Frescoes for Mr. Rockefeller's City (1933) was described by one critic as campaign poetry for Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. MacLeish also joined the League for Independent Political Action. The group, that included Lewis Mumford and John Dewey, promoted alternatives to a capitalist system they considered to be obsolete and cruel.

In August 1936 MacLeish wrote an article for New Masses where he urged the United States government to support the republicans in the Spanish Civil War. Along with John Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman and Ernest Hemingway, MacLeish helped to finance The Spanish Earth, a documentary film about the war.

Archibald MacLeish came into conflict with Henry Luce, the owner of Fortune Magazine, and Laird Goldsborough, the foreign affairs editor of Time Magazine, also part of the Luce's growing media empire. George Teeple Eggleston, who worked for the company at the time, has claimed that it was Goldsborough who persuaded Luce to support General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. According to Eggleston: "Time's conservative foreign news editor, Laird Goldsborough, promptly slanted all news stories in his department in favor of General Franco's rebel insurgents." Eggleston argued that MacLeish "promptly bombarded Luce memos denouncing Franco's coalition of landowners, the Church, and the army". Goldsborough responded by arguing: "On the side of Franco are men of property, men of God, and men of the sword. What positions do you suppose these sorts of men occupy in the minds of 700,000 readers of Time? ... They resent communists, anarchists, and political gangsters - those so-called Spanish Republicans."

MacLeish also joined other left-wing writers in the League of American Writers. Other members included Erskine Caldwell, Upton Sinclair, Malcolm Cowley, Clifford Odets, Langston Hughes, Carl Sandburg, Carl Van Doren, David Ogden Stewart, John Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett. MacLeish wrote at the time: "The real struggle of our time was not between communism and fascism but the much more fundamental struggle between democratic institutions on the one side and all forms of dictatorship, whatever the dictator's label, on the other."

MacLeish took a keen interest in world affairs and The Fall of the City (1937), a radio play about the growth of fascism in Europe, obtained a large audience in the United States. In April 1938 MacLeish published Land of the Free. The book included 338 lines of a poem by MacLeish and 88 photographs by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein and Ben Shahn. Most of the photographs came from the Farm Security Administration project and dealt with issues such as rural poverty and child labour.

In 1939 President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided to appoint MacLeish as librarian of Congress. Right-wing politicians objected to this proposal and J. Parnell Thomas a member of the House of Un-American Activities, argued that MacLeish was a communist. MacLeish, who had been a harsh critic of the American Communist Party for many years, replied "no one would be more shocked to learn I am a Communist than the Communists themselves." When the vote was taken in the Senate, sixty-three voted for MacLeish (eight voted against and twenty-five abstained) and he was appointed.

During the Second World War MacLeish wrote for the New Republic. He was also head of the Office of Facts and Figures. This brought him into conflict with J. Edgar Hoover, who tried to stop him employing left-wing figures such as Malcolm Cowley. Hoover complained that Cowley had been "associated with various Liberal and Communist groups." In January 1942, MacLeish replied that the FBI agents needed a course of instruction in history. "Don't you think it would be a good thing if all investigators could be made to understand that Liberalism is not only not a crime but actually the attitude of the President of the United States and the greater part of his Administration?"

MacLeish was unaware that he was also under investigation by Hoover and the FBI. The agency was particularly interested in his involvement with the League of American Writers and other anti-fascist groups in the United States and his pro-Russian stance after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. MacLeish's FBI file eventually ran to six hundred pages, longer than any other writer in the United States.

In November 1944 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed MacLeish as his assistant secretary of state for cultural and public affairs. Once again right-wing members of the Senate complained about the appointment of MacLeish. The vote was close with forty-three in favour, twenty-five against, and twenty-eight abstaining.

MacLeish's main task was to promote the idea of the United Nations to the American people. However, the job only lasted a few months as Harry S. Truman decided not to reappoint him after the death of Roosevelt on 12th April 1945.

In October 1952 Joseph McCarthy claimed that MacLeish had belonged to more Communist front organizations than any man he had investigated. Despite coming under increasing pressure, MacLeish bravely defended his left-wing friends during the McCarthyism era. A play about the irrational fear of communism, The Trojan Horse, appeared in 1952.

Archibald MacLeish was appointed professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard University in 1949. Other books by MacLeish include Poetry and Journalism (1958), Poetry and Experience (1961), The Collected Poetry of Archibald MacLeish (1963), The Dialogues of Archibald MacLeish and Mark Van Doren (1964), The Wild Old Wicked Man and Other Poems (1968), The Human Season (1972) and Riders on the Earth (1978).

On this day in 1995 Milovan �ilas died. Djilas was born in Montenegro, Yugoslavia, on 12th June, 1911. He became a member of the Yugoslav Communist Party while studying at Belgrade University in 1932 and was imprisoned for his political activities (1933-36). In 1938 Djilas was elected to the Central Committee of the Party and two years later a member of its Politburo.

The Yugoslavian government headed by Prince-Regent Paul allied itself with the fascist dictatorships of Germany and Italy. However, on 27th March 1941, a military coup established a government more sympathetic to the Allies. Ten days later the Luftwaffe bombed Yugoslavia and virtually destroyed Belgrade. The German Army invaded and the government was forced into exile.

Djilas joined his friend Josip Tito to help establish the partisan resistance fighters. Djilas was commander of the resistance forces in Montenegro and Bosnia during the war. In 1944 Tito sent Djilas to the Soviet Union where he had meetings with Joseph Stalin.

Initially the Allies provided military aid to the Chetniks led by Drazha Mihailovic. Information reached Winston Churchill that the Chetniks had began to collaborate with the Germans and Italians and at Teheran the decision was taken to switch this aid to Tito and the partisans.

In May 1944 a new government of Yugoslavia was established under Ivan Subasic. Tito was made War Minister in the new government. Djilas and his partisans continued their fight against the German Army and in October 1944 helped to liberate Belgrade.

In March 1945 Josip Tito became premier of Yugoslavia. Over the next few years he created a federation of socialist republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia). Djilas was vice president in Tito's government.

Tito had several disagreements with Joseph Stalin and in 1948 he sent Djilas as head of a Yugoslav delegation to meet Stalin in Moscow. Negotiations failed and later that year Tito took Yugoslavia out of the Comintern and pursued a policy of "positive neutralism". Influenced by the ideas of Djilas, Tito attempted to create a unique form of socialism that included profit sharing workers' councils that managed industrial enterprises.

Despite these reforms Djilas remained critical of how communism was developing in Yugoslavia and wrote about these issues in the Belgrade newspaper Borba and the political review, Nova Misao. In 1954 he was expelled from the party and lost all his government posts.

In 1955 Djilas published The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System. In his book Djilas argued that communism in Eastern Europe was not an egalitarian society that it claimed to be. Instead, he argued, the party had established privileges enjoyed by a small group of party members (the New Class). Djilas was arrested in November 1956 and charged with "slandering and writing opinions hostile to the people and the state of Yugoslavia." Djilas was eventually sentenced to nine years in prison.

Soon after his release in 1961 he published Conversations with Stalin. This was based on his meetings with Joseph Stalin during the Second World War. This book led to a further period in prison (1962-66).

Djilas remained a committed socialist but argued that the dictatorship of the New Class inevitably carried within it the seeds of its own destruction. These views were expressed in books such as Under the Colours (1971), Land Without Justice (1972), Unperfect Society: Beyond the New Class (1972), Memoir of a Revolutionary (1973), Parts of a Lifetime (1975), Wartime: With Tito and the Partisans (1980), Tito: the Story from Inside (1981), Of Prisons and Ideas (1986) and Rise and Fall (1986).

After the death of Josip Tito in 1981 Djilas strongly opposed the break-up of Yugoslavia and the nationalist warfare that followed. He wrote: "Our system was built only for Tito to manage. Now that Tito is gone and our economic situation becomes critical, there will be a natural tendency for greater centralization of power. But this centralization will not succeed because it will run up against the ethnic-political power bases in the republics. This is not classical nationalism but a more dangerous, bureaucratic nationalism built on economic self-interest. This is how the Yugoslav system will begin to collapse."

On this day in 2010 Dorothy Height died. Dorothy Height was born in Richmond, Virginia, on 24th March 1912. Her father, who was a builder, moved the family to Rankin, Pennsylvania, hoping to find a more racially tolerant environment.

Height won an essay contest, which brought the prize of a scholarship to Barnard College in New York City. However, when she arrived in 1929 she was excluded because of her race. She later recalled in Open Wide the Freedom Gates: "Although I had been accepted, they could not admit me. It took me a while to realize that their decision was a racial matter: Barnard had a quota of two Negro students per year, and two others had already taken the spots." Height went instead to New York University where she did an undergraduate and a master's degree in educational psychology.

After leaving university she became a welfare case-worker in Harlem. During this period she became friends with Langston Hughes and Mary McLeod Bethune. According to Godfrey Hodgson: "Whenever there was a lynching in the south, she and a group of friends would demonstrate in Times Square, wearing black armbands."

In 1944 Dorothy Height joined the national staff of the Young Women's Christian Association. Soon afterwards she met Martin Luther King while in Atlanta, Georgia. Although he was only a teenager it was the beginning of a long relationship.

In 1957 Height became director of the National Council of Negro Women. In the same year Martin Luther King joined with the Reverend Ralph David Abernathy and Bayard Rustin to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The new organisation was committed to using nonviolence in the struggle for civil rights, and SCLC adopted the motto: "Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed." Over the next few years Height worked closely with King in his various campaigns and eventually became chair of the executive committee of the Leadership Conference On Civil Rights, the umbrella organisation for the civil rights movement.

During the 1960 presidential election campaign John F. Kennedy argued for a new Civil Rights Act. After the election it was discovered that over 70 per cent of the African American vote went to Kennedy. However, during the first two years of his presidency, Kennedy failed to put forward his promised legislation.

Height took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on 28th August, 1963, was a great success. Estimates on the size of the crowd varied from between 250,000 to 400,000. Speakers included Martin Luther King (SCLC), Philip Randolph (AFL-CIO), Floyd McKissick (CORE), John Lewis (SNCC), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), Witney Young (National Urban League) and Walter Reuther (AFL-CIO). King was the final speaker and made his famous I Have a Dream speech.

When Martin Luther King was killed on 4th April 1968, Dorothy Height went to the White House and advised President Lyndon Johnson on how to minimize black protests and rioting.

In 1994 President Bill Clinton gave her the presidential medal of freedom. She retired as director of the National Council of Negro Women in 1997. She remained chairman of the group. Height commented: I hope not to work this hard all the rest of my life, but whether it is the council, whether it is somewhere else, for the rest of my life, I will be working for equality, for justice, to eliminate racism, to build a better life for our families and our children."