On this day on 14th December

On this day in 1775 Thomas Cochrane, the son of the ninth Earl of Dundonald, was born in Annsfield, Lanarkshire. He was educated at home and after a brief spell at the Chauvet Military Academy in London, he joined the Royal Navy. Cochrane became captain of H.M.S. Speedy in 1800 and he soon established a reputation for his daring and brilliant seamanship against the French Navy. Cochrane came into conflict with the authorities when they refused to support his campaign against corruption in the navy.

In 1805 he was a candidate for the parliamentary seat in Honiton. He recorded in his autobiography: "To the intense disgust of the majority of the electors, I refused to bribe at all, announcing my determination to 'stand on patriotic principles' which, in the electioneering parlance of those days, meant 'no bribery'. To my astonishment, however, a considerable number of the respectable inhabitants voted in my favour. Having had decisive proof as to the nature of Honiton politics, I made up my mind that the next time there was a vacancy in the borough, the seat should be mine without bribery. Accordingly, immediately after my defeat, I sent the bellman round the town, having first primed him with an appropriate speech, intimating that 'all who had voted for me, might repair to my agent and receive ten pounds ten.' The novelty of a defeated candidate paying double the current price expended by the successful one made a great sensation. The impression produced was simply this - that if I gave ten guineas for being beaten, my opponent had not paid half enough for being elected."

In 1806 Thomas Cochrane met the radical journalist William Cobbett, who had also been involved in attempting to expose corruption in the armed forces. The two men became close friends and Cobbett encouraged Cochrane to win election to the House of Commons where he would have an opportunity to expose those members of the armed forces who were misusing their power.

Cochrane was elected to represent Honiton in 1806. However, Cochrane's ideas were too progressive for the electors of Honiton and in 1807 he decided to accept the invitation to stand with Sir Francis Burdett as one of the two Radical candidates for the Westminster constituency.

After his election to the House of Commons Captain Cochrane spent much of his time at sea in the war against the French. When in Parliament, Cochrane made several speeches attacking corruption in the Royal Navy. The naval authorities were furious with Cochrane and he was demoted. Aware that he had lost the opportunity of advancing his naval career, Cochrane concentrated his efforts on campaigning for parliamentary reform.

Cochrane warned other MPs of the danger of revolution: "If the House does not reform itself, it will be reformed from outside with a vengeance." He urged them to reconsider their basic values: "Loyalty to the family must be merged into loyalty to the community, loyalty to the community into loyalty to the nation, and loyalty to the nation into loyalty to mankind. The citizen of the future must be a citizen of the world."

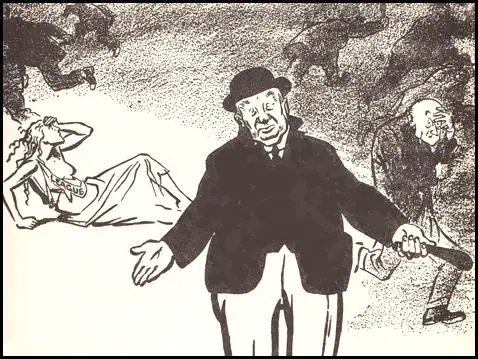

In 1814 Thomas Cochrane was accused with his uncle and his stockbroker of fraud on the stock market. Cochrane claimed he had been framed but he was found guilty of fraud and sentenced to a year's imprisonment, a fine of £1,000 and two hours in the pillory. When Sir Francis Burdett threatened to stand next to Cochrane in the pillory, this part of the sentence was withdrawn to avoid a riot taking place.

After his release from prison Cochrane gave support to Major John Cartwright and the formation of the Hampden Clubs. He also argued in favour of universal suffrage and spoke against the Gagging Acts.Cochrane once said: "If the individual is to be happy in the contemporary order, he must be open-minded with respect to new values and new arrangements."

In 1818 Cochrane resigned from the House of Commons and took up an appointment as commander of the Chilean Navy. After periods working for the governments of Peru and Brazil, Cochrane took command of the naval force that had been formed to assist the liberation of Greece.

In 1831 Thomas Cochrane became the tenth Earl of Dundonald. The following year, King William IV awarded him a free pardon for his alleged role in the 1814 stock market fraud. He was also reinstated as a Rear Admiral in the Royal Navy. Thomas Cochrane, Earl of Dundonald, died on 31st October 1860

On this day in 1829 John M. Langston was born in Louisa County, Delaware. His mother was a black slave and his father a Virginian plantation owner. An orphan by his fifth birthday, he was sent to be looked after by relatives in Ohio.

Langston was educated at Oberlin College and after graduating in 1849 he became active in the anti-slavery movement. At eighteen he made a speech on helping fugitive slaves at America's first National Black Convention.

A member of the Republican Party, Langston became involved in local politics and in 1855 was elected as the town clerk of the Brownhelm Township. Some members of the party were not only in favour the abolition of slavery but believed that freed slaves should have complete equality with white citizens. They also opposed the Fugitive Slave Act and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This group became known as Radical Republicans.

During the Civil War he helped recruit black soldiers to fight in the Union Army. After the 1860 elections the Radical Republicans became a powerful force in Congress. Several were elected as chairman of important committees. This included Thaddeus Stevens (Ways and Means), Owen Lovejoy (Agriculture), James Ashley (Territories), Henry Winter Davis (Foreign Relations), George W. Julian (Public Lands), Elihu Washburne (Commerce) and Henry Wilson (Judiciary).

A founder member of the National Equal Rights League, Langston was elected president of the organization in 1864. Five years later he helped establish the Colored National Labour Union. At the opening meeting Langston proudly announced: "In our organization we make no discrimination as to nationality, sex or colour."

In 1869 Langston was appointed professor of law of Howard University, Washington. A post he held until 1877 when he became the United States government's minister to Haiti. Langston returned to the United States in 1885 after being elected president of the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute.

Langston represented Virginia in the House of Representatives between September, 1890 to March, 1891. John M. Langston died in Washington on 15th November, 1897.

On this day in 1852 Daniel De Leon was born in the Dutch colony of Curacao. His parents sent him to Germany and the Netherlands to be educated and he arrived in the United States in 1874. Soon afterwards he found work as a teacher of Latin, Greek and Mathematics.

De Leon settled in New York and became a student and later a teacher at Columbia University. Converted to socialism by the writings of Edward Bellamy, De Leon joined the Knights of Labor and worked for Henry George in his campaign to become mayor of the city.

In 1890 De Leon joined the Socialist Labor Party (SLP) and the following year became the editor of its newspaper, The People. In 1891 he ran as SLP candidate for governor of New York and won 13,000 votes.

Over the next few years De Leon, Laurence Gronlund, Morris Hillquit and Abraham Cahan emerged as the main leaders of the party. De Leon, a Marxist, began arguing for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism. He claimed that as United States was the most developed capitalist country in the world it was "ripe for the execution of Marxian revolutionary tactics."

De Leon was highly critical of the trade union movement in America. Originally a member of the Knights of Labor, In 1895 he helped form the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance (STLA) as a revolutionary alternative to the conservative American Federation of Labour. The move was not very successful and after several years only had 20,000 members.

On the 27th June, 1905, Daniel De Leon and a group of radical trade unionists held a convention in Chicago. Those who attended the proceedings included Eugene Debs, Bill Haywood, Mother Jones and Lucy Parsons. At the meeting it was decided to form the radical labour organization, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

In 1908 the Wobblies, as they became known, split into two factions. The group headed by De Leon and Eugene V. Debs advocated political action through the Socialist Party and the trade union movement, to attain its goals. The other faction, led by Bill Haywood, believed that general strikes, boycotts and even sabotage were justified in order to achieve its objectives. Haywood's views prevailed and De Leon left the organization.

De Leon then went on to form the Workers' International Union in opposition to the Industrial Workers of the World. As the historian Paul Buhle has pointed out: "He was the first English-speaking intellectual to influence long-run trends in the American Left, Daniel De Leon could not build a successful socialist movement but he did elucidate powerful notions about the evolution of industrial society."

Daniel De Leon died in New York on 11th May, 1914. Over 30,000 people attended his funeral and his supporters remained dedicated to his principles and memory and reprinted his essays in every edition of Weekly People and circulated his pamphlets widely.

On this day in 1882 Helena Normanton, the daughter of William Normanton, a pianoforte manufacturer, was born in London on 14th December 1882. When Helena was aged four, her father, aged 33, was found dead with a broken neck in a railway tunnel. Her mother, Jane Normanton, moved to Brighton with her two young daughters. She ran a small grocery shop and also turned her family home at 4 Clifton Place into a boarding house.

Normanton was a talented student and in 1896 won a scholarship to York Place Science School (later renamed Margaret Hardy School, forerunner of Varndean School for Girls). She eventually became a pupil teacher but on the death of her mother in 1900 she left school to help run the family boarding house and look after her younger sister. The following year she moved to 11 Hampton Place, Hove, a boarding house owned by her aunt, Eliza Whitehead.

In 1903 Helena became a student at the Edge Hill Teachers' Training College in Liverpool. After qualifying in 1905 she taught history in Glasgow and London. Helena was for a time the private tutor to the sons of Baron Maurice de Forest, the Liberal Party MP for West Ham North. Normanton was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Members of the WSPU began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Normanton, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

Like the WSPU, the Women's Freedom League was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL were especially critical of the WSPU arson campaign.

Normanton, like most members of the Women's Freedom League, was a pacifist, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 the organisation refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL such as Charlotte Despard believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Council for a negotiated peace.

As well as campaigning for women's suffrage, Normanton wrote several pamphlets on the issue of women's pay. In Sex Differentiation in Salary (1914) she argued for equal pay for equal work. After the First World War she wrote: "During and after the war, many soldiers' wives and widows became the breadwinners for families. Should they be paid according to their sex or their work?"

In 1918 Normanton applied to be admitted to the Middle Temple. When this application was rejected because she was a woman, she took the case to the House of Lords. However, before the case could be heard, Parliament passed the Disqualification (Removal) Bill. Normanton immediately applied again and therefore became the first woman admitted as a student to the bar. After passing her exams she was called to the bar on 17th November 1922, a few months after Ivy Williams, had become the first woman to do so (but she did not appear in a court of law).

While a student Normanton married Gavin Bowman Clark (1873-1948). As Joanne Workman has pointed out: "Her application to retain her maiden name after her marriage attracted considerable public interest. Helena deplored the loss of a woman's identity on marriage and its disadvantageous legal results. While she believed in the respectability of retaining the title Mrs she also wished to maintain continuity of identity in her professional career." In 1924 she became the first married British woman to be issued a passport in her maiden name.

Normanton gained a great deal of fame "from her writing, public speaking, and feminist activities". This led to claims that she was guilty of advertising her services (forbidden by legal etiquette). In April 1923 she requested the bar council to hold a full inquiry into whether she had ever advertised herself. As this did not happen she curtailed her public speaking engagements and stopped writing for newspapers and magazines.

In 1924 Helena Normanton became the first female counsel in a case at the Old Bailey. The following year she became the first woman to conduct a case in the United States, that established American women's right to retain their maiden names. Despite these achievements her earning from legal work was so low she had to supplement her income by renting rooms in her house in Mecklenburgh Square, Bloomsbury. She also published two books on famous criminal cases, The Trial of Norman Thorne (1929) and The Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse (1931).

Helena Normanton campaigned for changes in matrimonial law. At the annual meeting of the National Council of Women in October 1934, her proposals were strongly attacked by the Mothers' Union. In 1938 Normanton was co-founder with Vera Brittain, Edith Summerskill and Helen Nutting of the Married Women's Association. The organisation sought equal relationships between men and women in marriage.

Helena Wojtczak remarked in Notable Sussex Women (2008): "In 1948 she became the first woman to lead the prosecution in a murder trial, and the following year became one of the first two women to be appointed King's Counsel. She was an excellent public speaker, wrote articles for various publications and books on a wide variety of subjects, from Shakespeare to buying a house."

In 1952 Helena Normanton made submissions on behalf of the Married Women's Association to the royal commission on marriage and divorce. She proposed that a husband should pay his wife an allowance from the family income. The MWA complained that this suggestion had been submitted to the royal commission "without previous circulation to executive or members". One member complained that her proposal of a housekeeping allowance for wives equated to "pocket money given to a child". As a result of these criticisms, Normanton resigned as president of the MWA.

Normanton was a pacifist and was a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. She also played a significant role in the campaign for a university in Brighton. In 1956 she made the first donation to the Sussex University appeal. She wrote at the time: "I make this gift in gratitude for all that Brighton did to educate me when I was left an orphan." This was followed by larger donations and she bequeathed the capital of her trust to the university. Helena Normanton died on 14th October, 1957, and is buried at St Wulfran's Churchyard in Ovingdean.

On this day in 1882 John Edward Simkin, the only son and youngest child of Mary and John Edward Simkin senior (born 1842, Bromley), a storekeeper and factory labourer, was born in Limehouse on, 14th December, 1882.

In the 1901 census, John Edward Simkin junior is described as an "envelope cutter". He was living with his widowed father, a fifty-nine year old carman (probably a driver of a horse-drawn tram), at 22 Rich Street, Limehouse, Tower Hamlets.

In 1910, John Simkin married Jane Hopkins in Shoreditch. The couple's first child Elsie was born in 1912. She died in Islington three years later. John Simkin was born on 17th January 1914 at No.13, Block B, Peabody's Buildings, Dufferin Street, Finsbury. At the time John Edward Simkin was working at the De La Rue & Company at their old established factory in Bunhill Row, Finsbury, London, known as the Star Works. Another two sons, John Edward Simkin (17th January, 1914) and William Valentine Simkin (14th February 1915).

In the early stages of the First World War he joined the Royal East Kent Regiment. He arrived at Boulogne with the 7th Battalion in July 1915. When he reached the Western Front at the Somme he was attached to the 178th tunneling company. Where possible, the military employed specialist miners to dig tunnels under No Man's Land. The main objective was to place mines beneath enemy defensive positions. When it was detonated, the explosion would destroy that section of the trench. The infantry would then advance towards the enemy front-line hoping to take advantage of the confusion that followed the explosion of an underground mine.

Soldiers in the trenches developed different strategies to discover enemy tunnelling. One method was to drive a stick into the ground and hold the other end between the teeth and feel any underground vibrations. Another one involved sinking a water-filled oil drum into the floor of the trench. The soldiers then took it in turns to lower an ear into the water to listen for any noise being made by tunnellers. When an enemy's tunnel was found it was usually destroyed by placing an explosive charge inside.

It appears that John Simkin was involved in tunneling under the German frontline on 29th August, 1915, when a mine exploded and he was killed with two other men. Five others in the 178th tunneling company were badly injured. John Edward Simkin was buried alive and his body has never been recovered. His name appears on the Thiepval War Memorial.

On this day in 1918 Constance Markiewicz was elected to Parliament. After the passing of the passing of the Qualification of Women Act, Constance, while in prison, stood as the Sinn Fein candidate for the St. Patrick's division of Dublin. She was the only woman who was successful in the 1918 General Election. However, like the seventy two Sinn Fein MPs, she did not attend the House of Commons in London.

On this day in 1918 Mary Macarthur, the Labour Party candidate in Stourbridge in the 1918 General Election, but like the others who opposed the First World War, she was defeated.

On this day in 1918 Christabel Pankhurst, the Women's Party candidate in Smethwick is defeated in the 1918 General Election. Christabel Pankhurst became one of the seventeen women candidates that stood in the election. The Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down so it could be a straight fight with the Labour Party. Christabel accused the Labour candidate, John E. Davidson, of being a Bolshevik. Davidson replied that far from being "corrupted and led by Bolshevists' the Labour Party stood for social reform along constitutional lines "without breaking a single window, firing a single pillar-box, or burning down a single church." Davidson beat Pankhurst by 775 votes.

On this day in 1939 Archibald Ramsay, the Tory MP for Peebles and Southern Midlothian complained about fascists in the UK being arrested. Ramsay did not say that they were all members of the Right Club. It was founded by Ramsay, in May, 1939. This secret society was an attempt to unify all the different right-wing groups in Britain. Or in the leader's words of "co-ordinating the work of all the patriotic societies". In his autobiography, The Nameless War, Ramsay argued: "The main object of the Right Club was to oppose and expose the activities of Organized Jewry, in the light of the evidence which came into my possession in 1938. Our first objective was to clear the Conservative Party of Jewish influence, and the character of our membership and meetings were strictly in keeping with this objective."

Members of the Right Club included William Joyce, Anna Wolkoff, Norah Dacre Fox, A. K. Chesterton, Francis Yeats-Brown, E. H. Cole, Lord Redesdale, 5th Duke of Wellington, Duke of Westminster, Aubrey Lees, John Stourton, Thomas Hunter, Samuel Chapman, Ernest Bennett, Charles Kerr, John MacKie, James Edmondson, Mavis Tate, Marquess of Graham, Margaret Bothamley, Lord Sempill, Randolph Stewart, 12th Earl of Galloway and Cecil Serocold Skeels.

Unknown to Ramsay, MI5 agents had infiltrated the Right Club. This included three women, Joan Miller, Marjorie Amor and Helem de Munck. The British government was therefore kept fully informed about the activities of Ramsay and his right-wing friends. Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the government passed a Defence Regulation Order. This legislation gave the Home Secretary the right to imprison without trial anybody he believed likely to "endanger the safety of the realm"

On 20th March, 1940, Archibald Ramsay asked the Minister of Information a question about the New British Broadcasting Service, a radio station broadcasting German propaganda. In doing so he gave full details of the wavelength and the time in the day when it provided programmes. His critics claimed he was trying to give the radio station publicity. Two Labour Party MPs, Ellen Wilkinson and Emanuel Shinwell, made speeches in the House of Commons suggesting that Ramsay was a member of a right-wing secret society. However, unlike MI5, they did not know he was the leader of the Right Club.

On 20th March, 1940, Archibald Ramsay asked the Minister of Information a question about the New British Broadcasting Service, a radio station broadcasting German propaganda. In doing so he gave full details of the wavelength and the time in the day when it provided programmes. His critics claimed he was trying to give the radio station publicity. Two Labour Party MPs, Ellen Wilkinson and Emanuel Shinwell, made speeches in the House of Commons suggesting that Ramsay was a member of a right-wing secret society. However, unlike MI5, they did not know he was the leader of the Right Club.

By this time Ramsay was being helped in his work by Anna Wolkoff, the daughter of Admiral Nikolai Wolkoff, the former aide-to-camp to the Nicholas II in London. Wolkoff ran the Russian Tea Room in South Kensington and this eventually became the main meeting place for members of the Right Club. In the 1930s Wolkoff had meetings with Hans Frank and Rudolf Hess. In 1935 her actions began to be monitored by MI5. Agents warned that Wolkoff had developed a close relationship with Wallis Simpson (the future wife of Edward VIII) and that the two women might be involved in passing state secrets to the German government.

In February 1940, Wolkoff met Tyler Kent, a cypher clerk from the American Embassy. He soon became a regular visitor to the Russian Tea Room where he met other members of the Right Club including Ramsay. Wolkoff, Kent and Ramsay talked about politics and agreed that they all shared the same views on Jews. Kent was concerned that the American government wanted the United States to join the war against Germany. He said he had evidence of this as he had been making copies of the correspondence between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Kent invited Wolkoff and Ramsay back to his flat to look at these documents. This included secret assurances that the United States would support France if it was invaded by the German Army. Kent later argued that he had shown these documents to Ramsay in the hope that he would pass this information to American politicians hostile to Roosevelt.

On 13th April 1940 Wolkoff went to Kent's flat and made copies of some of these documents. Joan Miller and Marjorie Amor were later to testify that these documents were then passed on to Duco del Monte, Assistant Naval Attaché at the Italian Embassy. Soon afterwards, MI8, the wireless interception service, picked up messages between Rome and Berlin that indicated that Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of German military intelligence (Abwehr), had seen the Roosevelt-Churchill correspondence.

Soon afterwards Anna Wolkoff asked Joan Miller if she would use her contacts at the Italian Embassy to pass a coded letter to William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw) in Germany. The letter contained information that he could use in his broadcasts on Radio Hamburg. Before passing the letter to her contacts, Miller showed it to Maxwell Knight, the head of B5b, a unit within MI5 that conducted the monitoring of political subversion.

On 18th May, Knight told Guy Liddell about the Right Club spy ring. Liddell immediately had a meeting with Joseph Kennedy, the American Ambassador in London. Kennedy agreed to waive Kent's diplomatic immunity and on 20th May, 1940, the Special Branch raided his flat. Inside they found the copies of 1,929 classified documents, including the secret correspondence between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Kent was also found in possession of what became known as Ramsay's Red Book. This book had the names and addresses of members of the Right Club and had been given to Kent for safe keeping.

Anna Wolkoff and Tyler Kent were arrested and charged under the Official Secrets Act. The trial took place in secret and on 7th November 1940, Wolkoff was sentenced to ten years. Kent, because he was an American citizen, was treated less harshly and received only seven years.

Archibald Ramsay was surprisingly not charged with breaking the Official Secrets Act. Instead he was interned under Defence Regulation 18B. Ramsay now joined other right-wing extremists such as Oswald Mosley and Admiral Nikolai Wolkoff in Brixton Prison. Some left-wing politicians in the House of Commons began demanding the publication of Ramsay's Red Book. They suspected that several senior members of the Conservative Party and members of the establishment, including Lord Rothermere, had been members of the Right Club. Some took the view that Ramsay had done some sort of deal in order to prevent him being charged with treason.

Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary refused to reveal the contents of Ramsay's Red Book. He claimed that it was impossible to know if the names in the book were really members of the Right Club. If this was the case, the publication of the book would unfairly smear innocent people. The government found it difficult to suppress the story and in 1941 the New York Times claimed that Ramsay had been guilty of spying for Nazi Germany: "Before the war he (Ramsay) was strongly anti-Communist, anti-semitic, and pro-Hitler. Though no specific charges were brought against him - Defence Regulations allow that - informed American sources said that he had sent to the German Legation in Dublin treasonable information given to him by Tyler Kent, clerk to the American Embassy in London."

Archibald Ramsay sued the owners of the New York Times for libel. In court Ramsay argued that if there had been any evidence of him passing secrets to the Germans he would have been tried under the Official Secrets Act alongside Anna Wolkoff and Tyler Kent in 1940. The newspaper owners were found guilty of libel but the case became a disaster for Ramsay when he was awarded a farthing in damages. As well as the extremely damaging publicity he endured, Ramsay was forced to pay the costs of the case.

On this day in 1947 Stanley Baldwin died. Baldwin resigned as prime minister on 28th May, 1937, following the successful coronation celebrations of George VI. After retiring from the House of Commons he was granted the title Earl Baldwin of Bewdley. Baldwin was critical of the government's appeasement policy. He complained to Anthony Eden that his own work "in keeping politics national instead of party" had been rendered worthless by the actions of Neville Chamberlain. Eden replied that Chamberlain was attempting to "return to class warfare in its bitterest form".

After the outbreak of the Second World War the public became hostile to both Baldwin and Chamberlain over their appeasement foreign policy in the 1930s. Baldwin was pleased when Winston Churchill became prime minister: "I think he is the right man at the moment and I always did feel that war would be his opportunity. He thrives in that environment."

Baldwin's long-time enemy, Lord Beaverbrook, was Minister of Supply, in 1942, and ordered that the wrought-iron gates that guarded his home, be commandeered for scrap. When this issue was discussed in the House of Commons, Captain Alan Graham, the Conservative M.P. for Wirral said that he was "aware that it is very necessary to leave Lord Baldwin his gates in order to protect him from the just indignation of the mob".

As Roy Jenkins pointed out: "Chamberlain's death left Baldwin more exposed. He became the best available villain for those who wished to fasten upon an individual to blame for Britain's plight. His mail became almost uniformly hostile... Some suggested that the whole estate and house ought to be taken over... He lost nearly all the glow of affection and respect in which he had retired. Most people forgot about him; and the majority of those who did not were unpleasant."

Lucy Baldwin died on 17th June, 1945. Eight days later Baldwin wrote to Joan Davidson: "I have been stunned by what has happened, and realization only follows slowly: I am not a hermit and I perform little duties towards my neighbours, but I have not yet got that control of myself that I must have before I venture forth even amongst my intimate friends."

The following year Baldwin stayed with the Davidsons. On his return he wrote a letter of thanks: "I hated leaving Norcott and I always have to screw myself up to coming back to Astley... My visit was a great joy to me, but I felt you were both working at full stretch and I think you are both carrying out just as much as you can I feel keenly my incapacity to be of any help... The atmosphere in your loved home has done me good, and the memory I always take away with me is very dear to me and for it I bless you... I can't express my feelings as easily as I used to: my pen runs dry and I have to pause for words."

Baldwin stayed at the Davidson's home for the last time in October 1947: "I was very happy at Norcott, as I always am, and I am grateful for much that you said. There are not many left to tell an octogenarian his faults in the spirit of love and not of criticism. I hope that I may improve and be asked again."

On this day in 1989 peace activist Andrei Sakharov died. Sakharov, the son of a science teacher, was born in Russia on 21st May 1921. An exceptional student he studied physics at Moscow State University and was awarded a doctorate in 1947 for his work on cosmic rays.

Sakharov played an important role in the development of the Soviet hydrogen bomb and in 1953 became the youngest man ever to be admitted as a full member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

In 1961 Sakharov spoke out against the plans of Nikita Khrushchev to test a 100-megaton hydrogen bomb in the atmosphere. He argued that the test would create widespread radioactive fallout. Sakharov caused further controversy when he published Progress, Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom in 1968. In the book he called for nuclear arms reductions. He also advocated the integration of the communist and capitalist systems to form what he called democratic socialism. As a result of the book Sakharov was removed from top-secret work and all his privileges removed.

In 1970 Sakharov joined with Valery Chalidze, Igor Shafarevich, Andrei Tverdokhlebov and Grigori Podyapolski to establish the Committee for Human Rights. In 1975 Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and three years later published Alarm and Hope.

In December 1979, Sakharov spoke out against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The following month the Soviet government stripped him of his honours and exiled him to the closed city of Gorky. His wife, Yelena Bonner, a human-rights activist, was also sent into exile.

Sakharnov and his wife remained in captivity until the Mikhail Gorbachev gained power in the Soviet Union. In December 1986 the couple were released and allowed to return to Moscow. Andrei Sakharov was elected to the Congress of People's Deputies in April 1989. However, Sakharov died nine months later in Moscow on 14th December, 1989.