Tunnelling and the First World War

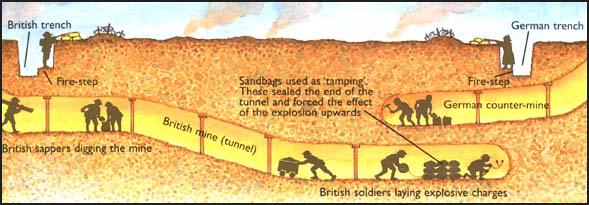

On the Western Front during the First World War, the military employed specialist miners to dig tunnels under No Man's Land. The main objective was to place mines beneath enemy defensive positions. When it was detonated, the explosion would destroy that section of the trench. The infantry would then advance towards the enemy front-line hoping to take advantage of the confusion that followed the explosion of an underground mine.

Soldiers in the trenches developed different strategies to discover enemy tunnelling. One method was to drive a stick into the ground and hold the other end between the teeth and feel any underground vibrations. Another one involved sinking a water-filled oil drum into the floor of the trench. The soldiers then took it in turns to lower an ear into the water to listen for any noise being made by tunnellers.

It could take as long as a year to dig a tunnel and place a mine. As well as digging their own tunnels, the miners had to listen out for enemy tunnellers. On occasions miners accidentally dug into the opposing side's tunnel and an underground fight took place. When an enemy's tunnel was found it was usually destroyed by placing an explosive charge inside.

Mines became larger and larger. At the beginning of the Somme offensive, the British denoted two mines that contained 24 tons of explosives. Another 91,111 lb. mine at Spanbroekmolen created a hole that afterwards measured 430 ft. from rim to rim. Now known as the Pool of Peace, it is large enough to house a 40 ft. deep lake.

In January, 1917, General Sir Herbert Plumer, gave orders for 20 mines to be placed under German lines at Messines. Over the next five months more than 8,000 metres of tunnel were dug and 600 tons of explosive were placed in position. Simultaneous explosion of the mines took place at 3.10 on 7th June. The blast killed an estimated 10,000 soldiers and was so loud it was heard in London.

Primary Sources

(1) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

Le Touquet consisted of a number of huge mine craters, roughly between the German front line and our own. In some cases the edge of one crater overlapped that of another. Companies of Royal Engineers, composed of specially selected British coal miners, worked in shifts around the clock digging tunnels towards the German line. When a tunnel was completed after several days of sweating labour, tons of explosive charges were stacked at the end and primed ready for firing. Careful calculations were made to ensure that the centre of the explosion would be bang under the target area.

This was an underground battle against time, with both sides competing against each other to blast great holes through the earth above. With listening apparatus the rival gangs could judge each other's progress, and draw conclusions. A continual contest went on. As soon as a mine was blasted, preparations for a new tunnel were started. On at least one occasion British and German miners clashed and fought underground, when the final partition of earth between them suddenly collapsed.

On the completion of one of the mines, the troops in the danger area withdrew when zero time for detonation was imminent. If the resultant crater had to be captured, an infantry storming party would be ready to rush forward and beat Jerry to it. Some of the craters measured over a hundred feet across the top, descending funnell-wise to a depth of at least thirty feet.

At the moment of explosion the ground trembled violently in a miniature earthquake. Then, like an enormous pie crust rising up, slowly at first, the bulging mass of earth crackled in thousands of fissures as it erupted. When the vast sticky mass could no longer contain the pressure beneath, the centre burst open, and the energy released carried all before it. Hundreds of tons of earth hurled skywards to a height of three hundred feet or more, many of the lumps of great size. A state of acute alarm prevailed as the deadly weight commenced to drop, scattered over a huge radial area from the centre of the blast.