On this day on 6th May

On this day in 1541 King Henry VIII orders English-language Bibles be placed in every church. In 1515 William Tyndale, a young priest, began work on an English translation of the New Testament. This was a very dangerous activity for ever since 1408 to translate anything from the Bible into English was a capital offence. In 1523 he travelled to London for a meeting with Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London. Tunstall refused to support Tyndale in this venture but did not organize his persecution. Tyndale later wrote that he now realized that "to translate the New Testament… there was no place in all England" and left for Germany in April 1524.

Tyndale argued: "All the prophets wrote in the mother tongue... Why then might they (the scriptures) not be written in the mother tongue... They say, the scripture is so hard, that thou could never understand it... They will say it cannot be translated into our tongue... they are false liars." In Cologne he translated the New Testament into English and it was printed by Protestant supporters in Worms in 1526.

Tyndale's Bible was heavily influenced by the writings of Martin Luther. This is reflected in the way he altered the meaning of certain important concepts. "Congregation" was employed instead of "church", and "senior" instead of "priest", "penance", "charity", "grace" and "confession" were also silently removed.

Melvyn Bragg has pointed out. Tyndale "loaded our speech with more everyday phrases than any other writer before or since". This included “under the sun”, “signs of the times”, “let there be light”, “my brother’s keeper”, “lick the dust”, “fall flat on his face”, “the land of the living”, “pour out one’s heart”, “the apple of his eye”, “fleshpots”, “go the extra mile” and “the parting of the ways”. Bragg adds: "Tyndale deliberately set out to write a Bible which would be accessible to everyone. To make this completely clear, he used monosyllables, frequently, and in such a dynamic way that they became the drumbeat of English prose."

William Tyndale arranged for these Bibles to be smuggled into England. Tyndale declared that he hoped to make every ploughboy as knowledgeable in Scripture as the most learned priest. The Bibles were often hidden in bales of straw. Most English people could not read or write, but some of them could, and they read it out aloud to their friends at secret Protestant meetings. They discovered that Catholic priests had taught them doctrines which were not in the Bible. During the next few years 18,000 copies of this bible were printed and smuggled into England.

Jasper Ridley has argued that the Tyndale Bible created a revolution in religious belief: "The people who red Tyndale's Bible could discover that although Christ had appointed St Peter to be head of his Church, there was nothing in the Bible which said that the Bishops of Rome were St Peter's successors and that Peter's authority over the Church had passed to the Popes... The Bible stated that God had ordered the people not to worship graven images, the images and pictures of the saints, and the station of the cross, should not be placed in churches and along the highways... Since the days of Pope Gregory VII in the eleventh century the Catholic Church had enforced the rule that priests should not marry but should remain apart from the people as a special celibrate caste... The Protestants, finding a text in the Bible that a bishop should be the husband of one wife, believed that all priests should be allowed to marry."

John Foxe tells the story of how Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London, arranged with Augustine Packingham, an English merchant who secretly supported Tyndale, to buy every copy of the translation's next edition. As a result, 6,000 copies were burnt of the steps of St Paul's Cathedral. Thomas More targeted Tyndale's friends. Richard Byfield, a monk accused of reading Tyndale, was one who died a graphically horrible death as described in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. More stamped on his ashes and cursed him." John Frith, who had had helped Tyndale with his translation, was also captured by More and suffered a slow death at Smithfield.

William Tyndale published The Obedience of a Christian Man in 1528. This was Tyndale's most influential book outside his Bible translations. His biographer, David Daniell, argued: "Tyndale wrote to declare for the first time the two fundamental principles of the English reformers: the supreme authority of scripture in the church, and the supreme authority of the king in the state. Tyndale makes many pages of his book out of scripture, and he is scalding about the corruptions and superstitions in the church. His arguments are carefully developed, and his experiences of ordinary life are wide-ranging. Contrasted with the New Testament church and faith, he describes the sufferings of the people at the hands, especially, of monks and friars, though the whole intrusive hierarchy, as he sees it, from the pope down."

Henry VIII was impressed with Tyndale's book. He especially liked the passage where he argued: "God in all lands hath put Kings, governors and rulers in his stead to rule the world through them. Whosoever therefore resisteth them resisted God... and shall be damned." In medieval society, the King and the Pope were the two dominating authorities. Tyndale's critics have pointed out that he wrote this book to he was attempting to form an alliance with Henry in his fight with Pope Clement VII.

Tyndale now began to work on the Old Testament. He was helped in this venture by Miles Coverdale and John Frith. He lived in Antwerp as a guest of Thomas Poyntz, an English merchant. In 1534 Tyndale was joined by John Rogers who was another talented translator. The continued export of Tyndale's Bibles into England upset conservatives such as Lord Chancellor Thomas More who insisted that anyone who read and distributed the Bible should suffer a "painful death". In 1530 Henry VIII gave orders that all English Bibles were to be destroyed. People caught distributing the Tyndale Bible in England were burnt at the stake. This attempt to destroy Tyndale's Bible was very successful as only two copies have survived.

Lacey Baldwin Smith accused William Tyndale of sharing More's paranoia: "More and his chief polemical rival, William Tyndale, did not hesitate to indulge in paranoid hyperbole. A conspiratorial approach to human affairs was just as central to Tyndale's thinking as it was to More's... Catholic or Protestant, conservative or reformer, each side depicted the opposition as a small band of evil men and women dressed in the cloak of conspiracy and carrying the dagger of sedition."

William Tyndale was visited secretly in 1531 by Thomas Cromwell's emissary, Stephen Vaughan, who invited him to return to England. "One evening in April 1531 Vaughan met Tyndale in a field outside Antwerp, and afterward wrote to Cromwell a long account of their conversation. Tyndale declared his strong loyalty to the king: he lived in constant poverty and danger to bring the New Testament to the king's subjects. Did the king, Tyndale asked, fear those subjects more than the clergy? Vaughan met Tyndale again in May. Tyndale movingly sent his promise that if the king would grant his people a bare text (of the scriptures, in their language), as even the emperor and other Christian princes had done, whoever made it, then he would write no more and submit himself at the feet of his royal majesty. A third meeting had the same result. Vaughan wrote twice again to Cromwell on Tyndale's behalf, with no effect."

Tyndale feared that he would be arrested if he returned to England. He told Vaughan that he would definitely not be returning while Sir Thomas More was in power. Another reason Tyndale did not return was that he was aware that it would not be long before he was in conflict with the King over the issue of his desire to divorce Catherine of Aragon. Tyndale told Vaughan that he could "not in conscience promote Henry's matrimonial cause".

Lord Chancellor More sent a close friend, Sir Thomas Elyot, to try to arrange the arrest of Tyndale. This ended in failure and the next person to try was Henry Phillips. He had gambled away money entrusted to him by his father to give to someone in London, and had fled abroad. Phillips offered his services to help capture Tyndale. After befriending Tyndale he led him into a trap on 21st May, 1535. Tyndale was taken at once to Pierre Dufief, the Procurer-General, who immediately raided Poyntz's house and took away all Tyndale's property, including his books and papers. Luckily, his work on the Old Testament was being kept by John Rogers. Tyndale was taken to Vilvorde Castle, outside Brussels, where he was kept for the next sixteen months.

Pierre Dufief had a reputation for hunting down heretics. He was motivated by the fact he was given a proportion of the confiscated property of his victims, and a large fee. Tyndale was tried by seventeen commissioners, led by three chief accusers. At their head was the greatest heresy-hunter in Europe, Jacobus Latomus, from the new Catholic University of Louvain, a long-time opponent of Erasmus as well as of Martin Luther. Tyndale conducted his own defence. He was found guilty but he was not burnt alive, as a mark of his distinction as a scholar, on 6th October, 1536, he was strangled first, and then his body was burnt. John Foxe reports that his last words were "Lord, open the king of England's eyes!"

William Tyndale's main enemy, Sir Thomas More, was executed on 6th July, 1535. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, were now the key political figures in England. They wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic and ordered to be burnt at the stake by Henry VIII eleven years before, for producing such a Bible. The edition they promoted, although mainly the work of Tyndale, had the name of Miles Coverdale on the cover. Cranmer approved the Coverdale version on 4th August 1538, and asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England.

Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September, 1538. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Coverdale Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm." the match.

On this day in 1856 Sigmund Freud, the son of Jacob Freud and Amalia Nathansohn Freud, was born in Freiberg, Austria. Both his parents were Jewish. His father's family originally came from Galicia but had "fled east from an anti-Semitic persecution, and that in the course of the nineteenth century they retraced their steps from Lithuania through Galicia to German Austria".

Jacob Freud was 40 years old when Sigmund was born and had been married twice before and already had two sons, Emmanuel and Philipp. He married Amalia when she was 20 years old, and she was younger than Emmanuel who was already married with a son. "The little Sigmund, therefore, was born an uncle, one of the many paradoxes his young mind had to grapple with."

Sigmund was Amalia's first child and although she had seven more children he "remained her favourite and most favoured child". He later wrote: "A man who has been the indisputable favourite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of a conqueror, that confidence of success that often induces real success." It has been argued by Beverley Clack that "Freud was viewed as something of a child prodigy by his doting mother, who did everything she could to cultivate a sense of her beloved boy as a fledgling intellectual".

Freud's father was less indulgent than his mother. At the age of two he would still wet the bed and he remembers being told off about this by his father and not his mother. "It was from such experiences that was born his conviction that typically it was the father who represented to his son the principles of denial, restraint, restriction, and authority; the father stood for the reality principle, the mother for the pleasure principle."

Freud later described the jealously he felt when a younger brother Julius was born when he was eighteen months old. He disliked the idea of sharing his mother with another child and admitted that he greeted his brother's birth "with adverse wishes and genuine childhood jealously". When Julius died seven months later, Freud was left with a "deeply implanted sense of guilt".

Jacob Freud had been wool merchant in Freiberg for twenty years. However, after the new Northern Railway by-passed the town, his business was directly affected. The family was forced to move and in 1860 they arrived in Vienna. Sigmund found moving house very distressing and it is claimed that for the rest of his life train journeys made him anxious. During the journey he saw his mother naked. Freud told the story to his friend, Wilhelm Fliess, forty years later, in a letter written in Latin.

After the death of Julius, Amalia Freud gave birth to Rosa (1860), Marie (1861), Adolfine (1862), Paula (1864) and Alexander (1866). At the age of seven Freud urinated in his parents' bed. His father was furious and exclaimed: "That boy will never amount to anything." Freud believed this incident had a dramatic impact on him: "This must have been a terrible affront to my ambition, for allusions to this scene occur again and again in my dreams, and are constantly coupled with enumerations of my accomplishments and successes." Later he had a great desire to say to his father: "You see, I have amounted to something after all."

As a boy Freud took a keen interest in Greek and Roman history. He also experienced anti-Semitism and he compensated by fantasizing himself as Hannibal, the Semitic Carthaginian general whose father had made him swear to "take vengeance on the Romans". As one of his biographers, Frederick Crews, has pointed out: "Such daydreaming became chronic as Sigmund, with dawning consciousness of the family's humble state, identified not just with Hannibal but also with the world-shaking Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon, among others."

In 1868 Jacob Freud came home and told a disturbing and dispiriting story. Out walking, Jacob was confronted by a man who knocked his hat from his head and yelled at him to get off the pavement because he was a Jew. Sigmund asked his father what he did about it. He replied that he picked up his hat. "Jacob's lack of heroism may have been pragmatic but it had a lasting effect on Freud's sense of his father."

In his autobiography Freud tells us he was a very successful student at school. "At the Gymnasium I was top of my class for seven years." He read widely outside the official syllabus and mastered Latin, Greek, French, English and Italian. According to one of his biographers: "In adolescence he was a typical overbearing big brother. He helped his sisters with their studies, but attempted to censor their reading matter, forbidding Balzac and Dumas, issued pompous homilies on their behaviour and complained about the noise from their piano practice. The piano was of course removed."

Freud grew up without any belief in a God or immortality. However, he was proud of his Jewish heritage. His close friend, Ernest Jones, claimed: "He (Freud) felt himself to be Jewish to the core, and it evidently meant a great deal to him. He had the common Jewish sensitiveness to the slightest hint of anti-Semitism and he made very few friends who were not Jews."

On this day in 1866, women's suffragist Minnie Turner is born. A supporter of women's suffrage, Turner became the honorary secretary of the Women's Liberal Association in Brighton in 1896. She was also a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). However, disappointed by the failure of the Liberal government to introduce legislation that would enable women to vote, Turner joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1908.

Turner ran her home, Sea View (13/14) Victoria Road, as a boarding house. Mary Clarke lived in her house while based in Brighton as a WSPU organiser. Turner was especially keen to cater for suffragettes and advertised her services in Votes for Women, The Suffragette, The Common Cause, The Vote and Women's Dreadnought.

Her advert stated: "Suffragettes spend your holidays in Brighton, central. Terms moderate." Some of the women who stayed at her boarding house included Emmeline Pankhurst, Constance Lytton, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney, Flora Drummond , Marie Naylor, Mary Leigh, Mary Phillips and Vera Wentworth.

In November 1910 Minnie Turner was arrested with Mary Clarke while taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons. She was released without charge. She was arrested for breaking a window in the Home Office in November 1911 and received a sentence of 21 days' in Holloway Prison.

Minnie Turner died in 1948.

On this day in 1890 Ross Tollerton was born in Ayr, Scotland. After being educated at Maxwell Town School, he joined the 1st Cameron Highlanders when he was fifteen. In 1906 he went to South Africa and later served in India.

After leaving the British Army in 1912 Tollerton worked in the Irvine Shipyard. As a reservist, he was recalled to the Cameron Highlanders at the outbreak of war in August 1914. Tollerton arrived in France in time to take part in the battles at the Marne and the Aisne Valley.

On the 14th September the Cameron Highlanders were involved in an attack on German lines. That morning the Highlanders lost 600 men from machine-gun fire. Lieutenant J. S. M. Matheson, Tollerton's commanding officer, was one of those wounded. Although Tollerton had been shot in the head, back and hand, he decided to carry Matheson to safety. As he was surrounded by the enemy, Tollerton could only move under cover of darkness. Matheson was extremely heavy and it took him three days before he got back to the British lines. Although Matheson had been shop in the spinal cord he survived.

Tollerton was awarded the Victoria Cross for his act of bravery. The medal was presented to Tollerton by King George V at a ceremony attended by 50,000 people at Glasgow Green on 18th May 1915. Promoted to Sergeant, Tollerton returned to the Western Front and survived the war.

After Tollerton was demobed he became a janitor at Bank Street School in Irvine. When the town war memorial was unveiled in April 1921, Tollerton was invited to lay the first wreath. Of the 2,000 men from the town of Irvine who served in the First World War, 238 of them had been killed.

Ross Tollerton health was badly damaged by his war experiences and he died aged forty-one on 7th May, 1931. Major J. S. M. Matheson, the man whose life Tollerton had saved sixteen years before, sent a wreath.

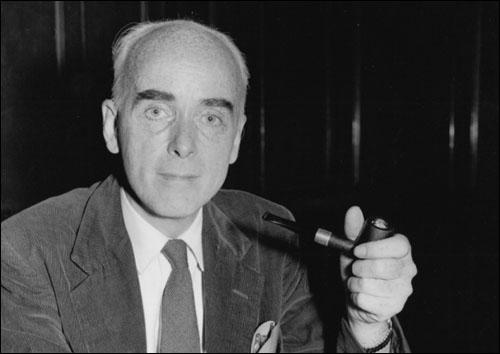

On this day in 1893 Margaret Postgate, the daughter of John Percival Postgate (1853–1926), Professor of Latin at the University of Liverpool and Edith Allen (1863–1962), was born in Cambridge..

Margaret was sent to Roedean in September of 1907. In her autobiography, Growing Up Into Revolution (1949) she claimed: "I have never understood why my parents sent me to Roedean. To remove me from the home was understandable. I was the wrong sort of cuckoo in a horridly alien nest. The cross was too wide, and Roedean was, emphatically, the wrong sort of school for me. But I would go further and say it was not a good sort of school at all. It was very expensive; I only got in as the winner of the single annual scholarship."

In October 1911 she entered Girton College. After reading the work of J. A. Hobson, H. G. Wells, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Brailsford she became a socialist, feminist and an atheist. In 1914 she left the University of Cambridge to take up a position teaching classics in St Paul's Girls' School.

On the outbreak of the First World War Cole became active in the peace movement. This brought her into contact with leading figures in the Independent Labour Party. In 1915 she began working part-time for the Fabian Research Department, where she met George Douglas Cole. He was leader of what became known as Guild Socialism. This movement advocated workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds. Other supporters included William Mellor, J. A. Hobson, Frank Horrabin, R. H. Tawney, Leonard Hobhouse and Samuel Hobson. This group formed the National Guilds League in 1915.

Margaret Cole joined the campaigned against conscription. After the passing of the Military Service Act, the No-Conscription Fellowship mounted a vigorous campaign against the punishment and imprisonment of conscientious objectors. About 16,000 men refused to fight. Most of these men were pacifists, who believed that even during wartime it was wrong to kill another human being. This included her brother, Raymond Postgate. and her lover, George Douglas Cole.

Margaret welcomed the Russian Revolution in November 1917. As she explained in her autobiography, Growing Up Into Revolution (1949): "On the way to the office we bought our newspapers and read with incredulous eyes that the Russian people, the workers, soldiers, and peasants, had really risen and cast out the Tsar and his government, who were to our minds the arch-symbols of black oppression in the world - far worse than the Prussians. On that day we did not work at all in the office; we danced round the tables and sang, and went to celebrate. Nor was it merely our small group that was delighted; throughout Britain everyone with an ounce of Liberalism in his composition rejoiced that whatever might come next tyranny had fallen, and thousands of them gathered in the Albert Hall and wept unashamedly as they paid tribute to those who had suffered in Siberia or in the Tsarist prisons. The news of Russia put immense heart into left-wing forces all over the country. It seemed as though there might be something good coming out of the war after all; for if the Russian people could overthrow their government, could not the Germans and the Austrians - or the French, or the British?"

Margaret married George Douglas Cole in August 1918. They moved to Oxford where Margaret taught evening classes and worked part-time for the Labour Research Department. She gave birth to Janet Elizabeth Margaret (February 1921) and Anne Rachel (October 1922). In 1924 the couple moved to Oxford where they both became involved in writing and teaching. Cole became Labour correspondent of the Manchester Guardian and after the publication of several books, including Guild Socialism Restated (1920), William Cobbett (1925) and Robert Owen (1925), Cole was appointed as Reader in Economics at University College.

In 1926 the couple gave support to the miners during the General Strike. They were regular visitors to the home of Beatrice Webb. She wrote in her diary on 5th September: "G.D.H. Cole and his wife - always attractive because they are at once disinterested and brilliantly intellectual and, be it added, agreeable to look at - stayed a weekend with us and later came on to the T.U.C. Middle age finds them saner and more charitable in their outlook... He is still a fanatic but he is a fanatic who has lost his peculiar faith... despite a desire to be rebels against all conventions, the Coles are the last of the puritans."

In 1931 Margaret and G.D.H. Cole created the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (SSIP). This was later renamed the Socialist League. Other members included William Mellor, Charles Trevelyan, Stafford Cripps, H. N. Brailsford, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, Frank Wise, David Kirkwood, Clement Attlee, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Ellen Wilkinson, Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh, Michael Foot and Barbara Betts. Margaret Cole admitted that they got some of the members from the Guild Socialism movement: "Douglas and I recruited personally its first list drawing upon comrades from all stages of our political lives." The first pamphlet published by the SSIP was The Crisis (1931) was written by Cole and Bevin.

According to Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977): "The Socialist League... set up branches, undertook to promote and carry out research, propaganda and discussion, issue pamphlets, reports and books, and organise conferences, meetings, lectures and schools. To this extent it was strongly in the Fabian tradition, and it worked in close conjunction with Cole's other group, the New Fabian Research Bureau." The main objective was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies.

In April 1933 G.D.H. Cole, R. H. Tawney and Frank Wise, signed a letter urging the Labour Party to form a United Front against fascism, with political groups such as the Communist Party of Great Britain. However, the idea was rejected at that year's party conference. The same thing happened the following year. Although disappointed, the Socialist League issued a statement in June 1935 that it would not become involved in activities definitely condemned by the Labour Party which will jeopardise our affiliation and influence within the Party."

Stafford Cripps was another advocate for an United Front: "Up till recent times it was the avowed object of the Communist Party to discredit and destroy the social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party, and so long as that policy remained in force, it was impossible to contemplate any real unity... The Communists had... disavowed any intention, for the present, of acting in opposition to the Labour Movement in the country, and certainly their action in many constituences during the last election gives earnest of their disavowal." Aneurin Bevan added: "It is of paramount importance that our immediate efforts and energies should be directed to organising a United Front and a definite programme of action."

In 1936 the Socialist League joined forces with the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Independent Labour Party and various trades councils and trade union brances to organize a large-scale Hunger March. Aneurin Bevan argued: "Why should a first-class piece of work like the Hunger March have been left to the initiative of unofficial members of the Party, and to the Communists and the ILP... Consider what a mighty response the workers would have made if the whole machinery of the Labour Movement had been mobilised for the Hunger March and its attendant activities."

Although Margaret Cole and G.D.H. Cole were seen as major figures on the left, Beatrice Webb believed that they now moderated their opinions. In a diary entry on 20th July 1936 she wrote. "Our old friends the Coles came for the night; middle-aged and thoroughly stabilized in all their relationships, endlessly productive of books, whether economic and historical treatises or detective stories, mutually devoted partners and admirable parents of their promising children, they lead their little troop of admiring disciples along the middle way of politics, rather to the right of the aged Webbs - a curious commentary on the world-be revolutionary guild socialist movements of the second decade of the twentieth century."

The United Front campaign opened officially with a large meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 24th January, 1937. Three days later the Executive of the Labour Party decided to disaffiliated the Socialist League. They also began considering expelling members of the League. G.D.H. Cole and George Lansbury responded by urging the party not to start a "heresy hunt".

Arthur Greenwood was one of those who argued that the rebel leader, Stafford Cripps, should be immediately expelled. Ernest Bevin agreed: "I saw Mosley come into the Labour Movement and I see no difference in the tactics of Mosley and Cripps." On 24th March, 1937, the National Executive Committee declared that members of the Socialist League would be ineligible for Labour Party membership from 1st June. Over the next few weeks membership fell from 3,000 to 1,600. In May, Margaret Cole and other leading members decided to dissolve the Socialist League.

Margaret Cole and her husband worked together to produce Intelligent Man's Review of Europe Today (1933) and The Condition of Britain (1937). She followed this by two books on her own: The New Economic Revolution (1938) and Marriage Past and Present (1938), which outlined a theory of socialist feminism. She lost her belief in pacifism with the rise of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany and as a result, she gave her full support to Britain's involvement in the Second World War.

A Labour Party member of the London County Council, Cole was an important figure in the early experiments with comprehensive education. As well as editing the diaries of Beatrice Webb, Cole also wrote several books including an autobiography, Growing Up into Revolution (1949), The Story of Fabian Socialism (1961) and G. D. H. Cole (1971).

According to her biographer, Marc Stears: "Towards the end of her husband's life Margaret Cole increasingly turned to historical studies as she attempted to document the considerable contribution that the couple and their friends had made to the British left.... She broke an informal agreement with R. H. Tawney by producing the first edited collection of articles on the work of Beatrice Webb, generating ill feeling which she perpetuated after his death... Despite these controversies, and a reputation for being personally abrasive, Margaret Cole was still generally respected on the left in the post-war world."

Margaret Cole died in a nursing home at Goring-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, on 7th May 1980, the day after her eighty-seventh birthday.

On this day in 1910 King Edward VII dies. Edward became king on the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. Although he was 59 when he became king, he restored some vitality to the monarchy. He made several royal visits and helped to prepare the way for international treaties with France and Russia. The king took a particular interest in military matters. He opposed attempts to reduce public spending on the armed forces and was a strong advocate of the Dreadnought building campaign.

Politically, the king favoured the Conservatives. He was totally opposed to the campaign by the NUWSS and the WSPU to achieve the vote for women. He disliked the Liberals, especially those such as Henry Campbell-Bannerman and Dave Lloyd George who had opposed the Boer War.

Edward VII was disappointed when the 1906 General Election brought the Liberals to power. Attempts to redistribute wealth resulted in Herbert Asquith and his government coming into conflict with the House of Lords.

After the Lords had rejected the People's Budget in 1909, Herbert Asquith and his chancellor, David Lloyd George, asked the king to create a large number of new Liberal peers to give the government a majority in the House of Lords. The king refused, insisted that the issue should be put to the electorate in a General Election to make sure that the public supported reform of the House of Lords.

In the middle of this dispute, the king became very ill. Edward VII died at Buckingham Palace on 6th May, 1910, leaving the constitutional crisis to be solved by his son, George V.

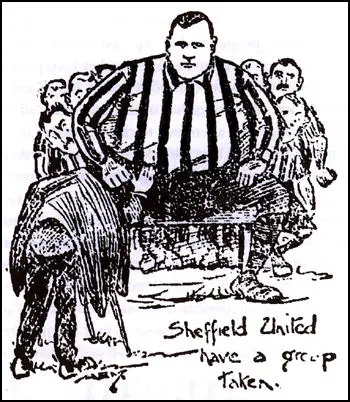

On this day in 1916 William Foulke writes about being the largest man who ever played football in the London Evening News..

As the biggest man who ever played football, I have naturally had a few stories told about me, and I should just like to say that some of them are stories.You may have heard that there was a very great rivalry between the old Liverpool centre forward Allan and myself, that prior to one match we breathed fire and slaughter at each other, that at last he made a rush at me as I was saving a shot, and that I dropped the ball, caught him by the middle, turned him clean over in a twinkling, and stood him on his head, giving him such a shock that he never played again.

Well, the story is one which might be described as a "bit of each". In reality, Allan and I were quite good friends off the field. On it we were opponents, of course, and there's no doubt he was ready to give chaff for chaff with me. What actually happened on the occasion referred to was that Allan (a big strong chap, mind you) once bore down on me with all his weight when I was saving.

I bent forward to protect myself, and Allan, striking my shoulder, flew right over me and fell heavily. He had a shaking up, I admit, but quite the worst thing about the whole business was that the referee gave a penalty against us and it cost Sheffield United the match.

On this day in 1952 Maria Montessori, died in Noordwijk, Holland.

Maria Montessori was born in Italy on 31st August, 1870. After graduating from medical school in 1896 Montessori became the first woman in Italy to become a doctor.

Montessori returned to university in 1901 to study psychology and philosophy. Three years later she became professor of anthropology at the University of Rome.

In 1906 Montessori left the university in order to work with sixty young working class children in the San Lorenzo district of Rome. Soon afterwards she founded the Casa dei Bambini (Children's House) where she developed what became known as the Montessori method of education. This method of teaching was based on spontaneity of expression and freedom from restraint.

In 1913 Montessori went to the United States where with the help of Alexander G. Bell founded the Montessori Educational Association in Washington. She also joined with Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Mabel Vernon, Olympia Brown, Mary Ritter Beard, Belle LaFollette, Helen Keller, Dorothy Day and Crystal Eastman to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS).

Montessori established a research institute in Spain and in 1919 she began a series of teacher training courses in London. In 1922 she was appointed a government inspector of schools in Italy.

An opponent of Benito Mussolini, Montessori was forced to leave Italy in 1934. She moved to Spain until General Francisco Franco and his nationalist forces defeated the republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

Montessori established training centres in the Netherlands (1938), India (1939) and England (1947). Maria Montessori, who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949, 1950 and 1951, died in Noordwijk, Holland, on 6th May, 1952.

On this day in 1953 Cedric Belfrage appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). According to Glenn Fowler, of The New York Times, the main reason for this was for his work in the "Psychological Warfare Division" in West Germany. Belfrage and James Aronson were accused of having approved "Communists to publish newspapers".

His son, Nicholas Belfrage, later recalled: "One morning I heard on the radio that the band leader Artie Shaw and the journalist Cedric Belfrage were to appear that day before HUAC. I knew it was coming but I was terrified nonetheless, because at that time there was a general atmosphere of fear and I thought I stood a good chance of being beaten up at my Bronx school or at least ostracised by my friends. In the event none of my contemporaries ever mentioned it, though my teacher, one Bessie Coyne whose adoration for McCarthy was matched only by her loathing of Communists and Brits (I was deemed to be both) inquired of me before a packed and silent class: 'Who are you going to kill today, Belfrage?' I was 13 at the time."

Belfrage refused to answer questions put to him by Harold H. Velde because "whatever answers I would give would be used to crucify me and other innocent persons". Another HUAC member, Bernard W. Kearney, told Belfrage: "I'm going to contact immigration authorities and find out why you are still in this country. I think you're the type to be deported immediately."

Belfrage later argued that Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn were determined to bring an end to the National Guardian as it was one of his major critics. "McCarthy struck red gold: two subversive army officers who, after laboring to create a 'red press' in Germany, had returned to establish one at home - a paper now leading the fight for the Rosenbergs, at whose trial Cohn had been an assistant prosecutor."

Later that month Belfrage was arrested and taken to Ellis Island, at that time, the immigration detention centre. On 10th June, 1953, he was freed by Federal District Judge Edward Weinfeld. In a statement issued by Weinfeld he argued: "If for the long period of seven years following... the immigration and other government officials did not consider Belfrage's presence and activities inimical to the nation's welfare and a threat to its security, it is difficult to understand how, overnight, because of his assertion of a constitutional privilege, he has become such a menace to the nation's safety that it is now necessary to jail him without bail."

Cedric Belfrage was eventually deported on 15th August 1955. "America banished one of its most devoted sons last week in the person of Cedric Henning Belfrage, editor of the newspaper. With his wife, the Guardian editor sailed at noon, Monday, August 15, on the Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam for his native England under a deportation order demanded 27 months ago by Senator Joseph McCarthy." The following year Belfrage published The Frightened Giant: My Unfinished Affair with America (1956).

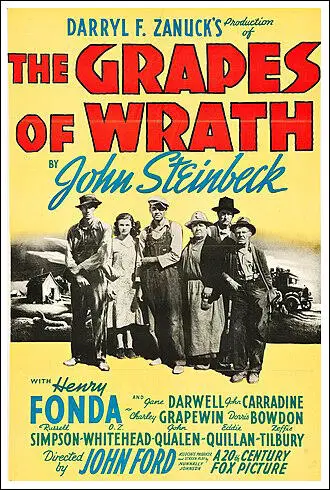

On this day in 1940 John Steinbeck is awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939). This novel of a family fleeing from the dust bowl of Oklahoma was made into a film directed by John Ford and featuring Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, John Carradine, Shirley Mills, John Qualen and Eddie Quillan.