On this day on 2nd March

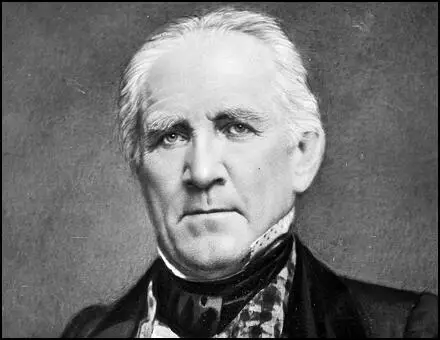

On this day in 1793 Samuel Houston was born in Rockbridge County, Virginia, on 2nd March, 1793. The family moved to Maryville, Tennessee, in 1807, where he was brought up by his widowed mother. In his youth he spent a lot of time with a group of Cherokees and learnt about their language and culture.

He joined the army and took part in the fighting against the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend, Alabama, on 28th March, 1814. Houston was an impressive soldier and under the command of Andrew Jackson reached the rank of second lieutenant. However, he resigned from the army in 1818 after being criticised for being too sympathetic to the plight of the Native Americans.

Houston studied law and opened up an office in Lebanon, Tennessee. Later that year he was elected district attorney at Nashville. In 1821 he was appointed Major General of Militia.

In 1823 Houston was elected to Congress and four years later became Governor of Tennessee. After a brief, unhappy marriage, Houston resigned as governor and went to like with the Cherokees. He made several trips to Washington to lobby for better treatment for Native Americans.

In April 1833 President Andrew Jackson asked Houston to go to Texas to negotiate with Native Americans in order to obtain the safe passage of American traders wanting to work in Mexican territory.

Houston gradually became involved in the campaign for against Mexican rule in Texas and in November, 1835, was elected Major General of the Texas Army. After the outbreak of the Texas Revolution Houston ordered his men to take San Antonio de Bexar. On 7th December a group of volunteers led by Ben Milam attacked the town. After the death of Milam James Bowie took over the leadership of the rebels. After two more days of fighting General Perfecto de Cos called for negotiations to take place. COs offered the rebels control of San Antonio de Bexar in exchange for his men being allowed to return to Mexico.

In January 1836 William Travis was given command of the regulars and James Bowie the volunteers based at San Antonio de Bexar. General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna and 7,000 Mexican troops arrived back in San Antonio on 23rd February, 1836. About 200 Texans took refuge in the fortified grounds of the Alamo. Bowie was struck down with typhoid and Travis eventually took over sole command of the fortress.

Houston signed the declaration of Texas independence on 2nd March, 1836. Two days later he was elected commander-in-chief of the army.

General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna now became determined to take the Alamo. He ordered the shelling of the fortress but the Texans refused to surrender. On 6th March the Mexican army stormed the fortress. During the battle 189 Texans were killed. This included William Travis, James Bowie and Davy Crockett. It is estimated that 1,500 Mexicans died during the fighting.

Samuel Houston and his small army retreated eastward following the fall of the Alamo. When Houston reached Buffalo Bayou he took up a defensive position by the River San Jacinto. General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna and his army of 1,500 men arrived across the prairie on 20th April. After coming under artillery fire the Mexicans moved back to some trees that provided them some protection from the Texans.

On 21st April 1836, Houston sent a small party of men under the leadership of Deaf Smith, to destroy Vince's Bridge and therefore cutting off the only means of escape. Edward Burleson, as commander of the First Regiment, led the attack on the Mexicans and organized resistance ended within 20 minutes. About 630 Mexicans were killed and 730 soldiers, including General Santa Anna, were captured. Texan casualties included 16 killed and 24 wounded.

Houston negotiated with Santa Anna who eventually agreed to withdraw all Mexican troops from Texas. On 22nd October, 1836, Houston became the first president of the Republic of Texas.

In 1845 Houston played an important role in the admission of Texas into the Union. He also served as a United States Senator from 1846 to 1859. Houston also became Governor of Texas but opposed secession from the Union and after the outbreak of the American Civil War attempted to get Texas to remain neutral. His attempts failed and Houston therefore retired to his farm at Huntsville.

Samuel Houston died at Huntsville, Texas, on 23rd July, 1863.

On this day in 1810 Leo XIII was born. Vincenzo Gioacchino Pecci, the son of Count Ludovico Pecci, was born in Carpineto on 2nd March, 1810. At the age of eight he was sent to study at the Jesuit school in Viterbo.

After taking a degree in law he was appointed by Pope Gregory XVI as a domestic prelate in 1837. He was sent to Belgium as nuncio in 1843 and three years later became Archbishop of Perugia. In 1853 he was created a cardinal by Pope Pius IX.

Pecci became Pope Leo XIII in 1878. He held enlightened views and in 1883 opened the archives of the Vatican for historical investigations.

Leo XIII was concerned about the growing support for Socialism in the world. In 1891 he published the encyclical On the Condition of the Working Class. In this document he called for far-reaching reforms to create a more just society and to avoid the dangers of a violent revolution.

In 1894 Leo XIII instructed the clergy, monarchists and all Catholics in France to accept the French Republic. He also encouraged the French government to form an alliance with Russia in order the counter the military threat of Germany. Pope Leo XIII died on 20th July, 1903.

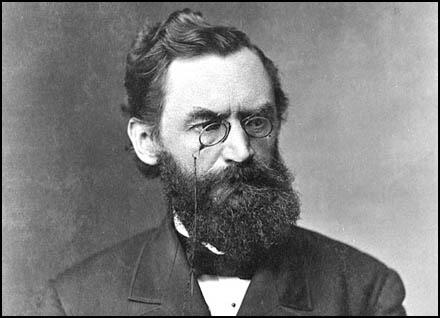

On this day in 1829 Carl Schurz was born in Cologne, Germany. While studying at the University of Bonn he became involved in radical politics. Schurz took part in the 1848 German Revolution and was afterwards forced to flee to Switzerland.

Schurz spent time in France and England before emigrating to the United States in 1852. Schurz and his wife lived in New York for a while before buying a farm in Watertown, Wisconsin. In 1856 Margarethe Schurz founded the first kindergarten in America. A strong supporter of universal suffrage, Schurz once wrote: "Our ideals resemble the stars, which illuminate the night. No one will ever be able to touch them. But the men who, like the sailors on the ocean, take them for guides, will undoubtedly reach their goal."

A leading member of the Republican Party, in 1860 Schurz campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. After the election, President Lincoln appointed Schurz as U.S. envoy to Spain.

Schurz was an active campaigner against slavery and on the outbreak of the American Civil War joined the forces of the Union Army. He helped recuit Germans living in New York before being asked to negotiate with European governments on behalf of Abraham Lincoln.

On his return to the United States, Schurz served under General John Fremont, the commander of the Department of the West. Soon afterwards he was given the rank of brigadier general and placed in command of the 3rd Division of the Army of Virginia (26th June, 1862 to 12th September, 1862).

Schurz also commanded the 3rd Division of the Army of Potomac (12th September, 1862 to 2nd April, 1863) and took part in the battles at Bull Run (July, 1862) and Fredericksburg (December, 1862). After the battle he was promoted to the rank of major general, replacing his friend and fellow German, Franz Sigel. Schurz also took part in the battle at Chancellorsville (May, 1863) and Gettysburg (July, 1863) before being given command of the 3rd Division of the Army of the Cumberland (25th September, 1863 to 21st January, 1864).

After the war Carl Schurz worked as the Washington correspondent of the New York Tribune. This was followed by a period as editor-in-chief of the Detroit Post. In 1867 he became editor of the German language newspaper, the Westliche Post, in St. Louis, Missouri.

Schurz remained active in the Republican Party and in 1869 was elected to the Senate. In 1872 he, like many Radical Republicans, supported Horace Greeley against Ulysses S. Grant, the official Republican candidate. Despite the efforts of Schurz and his close friend in Missouri, Joseph Pulitzer, Grant won the presidential election by 286 electoral votes to 66.

In 1877 President Rutherford Hayes appointed Schurz as his secretary of the interior. Over the next four years Schurz introduced civil service reforms and made improvements to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

After leaving office in 1881 Carl Schurz returned to journalism and became managing editor of the New York Evening Post. He also wrote for Harper's Weekly, The Nation and had several books published including The Life of Henry Clay (1887) and Abraham Lincoln (1891). Carl Schurz died on 14th May, 1906.

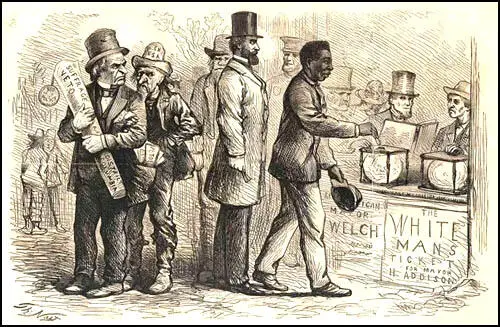

On this day in 1867 Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act. The Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution was passed by Congress in 1867. The amendment was designed to grant citizenship to and protect the civil liberties of recently freed slaves. Most Southern states refused to ratify this amendment and therefore Radical Republicans such as Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, Benjamin Wade, Henry Winter Davies and Benjamin Butler urged the passing of further legislation to impose these measures on the former Confederacy.

Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act on 2nd March, 1867. The South was now divided into five military districts, each under a major general. New elections were to be held in each state with freed male slaves being allowed to vote. The act also included an amendment that offered readmission to the Southern states after they had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment and guaranteed adult male suffrage. President Andrew Johnson immediately vetoed the bill but Congress re-passed the bill the same day.

Andrew Johnson consulted General Ulysses S. Grant before selecting the generals to administer the military districts. Eventually he appointed John Schofield (Virginia), Daniel Sickles (the Carolinas), John Pope (Georgia, Alabama and Florida), Edward Ord (Arkansas and Mississippi) and Philip Sheridan (Louisiana and Texas).

It soon became clear that the Southern states would prefer military rule to civil government based on universal male suffrage. Congress therefore passed a supplementary Reconstruction Act on 23rd March that authorized the military commanders to supervise elections and generally to provide the machinery for constituting new governments. Once again Andrew Johnson vetoed the act on the grounds that it interfered with the right of the American citizen to "be left to the free exercise of his own judgment when he is engaged in the work of forming the fundamental law under which he is to live."

The first two Reconstruction Act were followed by a series of supplementary acts that authorized the military commanders to register the voters and supervise the elections. As a result of these measures all of the states had returned to the Union by 1870.

On this day in 1867 Howard University was established in Washington by a charter of the U.S. Congress. Instigated by the Radical Republicans it was named after General Oliver Howard, a Civil War hero and commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees and a leading figure in the Freeman's Bureau.

The stated purpose of Howard University when it was founded was to create "a college for the instruction of youth in the liberal arts and sciences". The Freeman's Bureau provided most of the early financial support and the majority of its students were African American. Within two years the university consisted of colleges of Liberal Arts and Medicine.

In the 1960s the faculty and student body played an important role in the civil rights movement. Howard University now operates its own hospital, radio and television stations, hotel and publishing house. In 2000 the university had 10,248 students (86 per cent African American).

On this day in 1876 Pope Pius XII was born. Eugenio Pacelli was born in Rome on 2nd March, 1876. He attended Capranica Seminary and was ordained in 1899. As well as carrying out parish work he took a degree in Canon and Civil Law at the Apollinaris.

During the First World War he was involved in organizing humanitarian relief. In 1917 Pope Benedict XV sent him to Germany where he had a meeting with Kaiser Wilhelm II but the peace plan was rejected.

When the Weimar Republic was established after the war Pope Benedict XV created a nunciature and Pacelli was sent to Berlin. He remained in Germany until 1929 when he was made a cardinal.

In 1929 Pope Pius XI signed the Lateran Treaty with Benito Mussolini which brought into existence the Vatican state. The following year Pacelli became Secretary of State. This involved him in diplomatic work and included a visit to the United States.

Pope Pius XI condemned the Nuremberg Laws in July, 1938, and was preparing an encyclical against anti-Semitism, when he died on 10th February, 1939. Pacelli now became Pope Pius XII.

After the outbreak of the Second World War Pius XII issued a five-point peace programme. When this failed he organized humanitarian work for prisoners of war and refugees. However, he did not openly speak out against the atrocities being carried out in Nazi Germany. Nor did he do very much to save the Jews in Rome.

Pius XII refused the request of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in September 1942 to denounce the Nazi persecution of the Jews in Europe. The nearest he came to public condemnation of the Holocaust was in his Christmas message of 1942 when he said: "Humanity owes this vow to those hundreds of thousands who, without any fault of their own, sometimes only by reason of their nationality or race, are marked down for death or gradual extinction." However, he resisted mentioning the Jews by name.

Pius XII was also criticised for his failure to act in Croatia during the Second World War. Croatia, a Catholic state, was responsible for the killing of 487,000 Orthodox Serbs, 27,000 Gypsies and around 30,000 Jews between 1941 and 1945.

After the war Pius XII gave his support for the United Nations. He also introduced reforms that made it easier for Catholics to attend Mass and receive Holy Communion. Pope Pius XII died on 9th October, 1958.

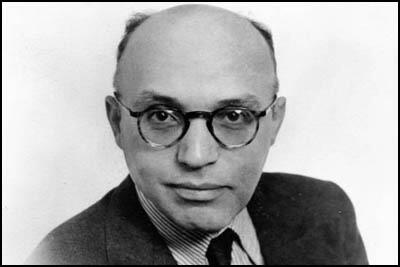

On this day in 1900 Kurt Weill was born in Dessau, Germany. He studied music under Engelbert Humperdinck and Ferruccio Busoni and his early works included two symphonies.

In 1927 Weill collaborated with the writer, Bertolt Brecht to produce the musical play, Mahagonny. They then produced The Threepenny Opera (1928). Although based on The Beggar's Opera that was originally produced in 1728, Brecht added his own lyrics that illustrated his growing belief in Marxism. Weill also worked with Brecht on Happy End (1929).

Weill was a socialist and when Hitler gained power in 1933 he was forced to flee from Germany. He settled in the United States where he soon became involved in the Group Theatre in New York. Founded by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg, the Group was a pioneering attempt to create a theatre collective, a company of players trained in a unified style and dedicated to presenting contemporary plays. Others involved in the group included Elia Kazan, Stella Adler, John Garfield, Luther Adler, Will Geer, Howard Da Silva, Franchot Tone, John Randolph, Joseph Bromberg, Michael Gordon, Paul Green, Clifford Odets and Lee J. Cobb. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

In 1936 Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford of the Group Theatre commissioned Weill to write the music for Johnny Johnson, an anti-war play written by Paul Green. Over the next few years Weill wrote the music for several theatre productions including Lady in the Dark (1940), Street Scene (1946) and Lost in the Stars (1949).

Weill wrote the music for several Hollywood films including You and Me (1938), Blockade (1938), Knickerbocker Holiday (1944), Lady in the Dark (1944), Where Do We Go From Here (1945), Salute to France (1946) and One Touch of Venus (1948).

Kurt Weill died in New York on 3rd April, 1950.

On this day in 1905 Marc Blitzstein was born. Marc Blitzstein, the son of a wealthy banker, was born in Philadelphia on 2nd March, 1905. His father was a socialist, but Blitzstein later recalled that he was "as modern in social thinking as he was conservative in musical taste". A child prodigy, he performed as a soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra when he was only fifteen. He studied at the Curtis Institute of Music and later trained with Nadia Boulanger in Paris and Arnold Schonberg in Berlin.

Blitzstein wrote plays as well as music and joined theGroup Theatre in New York City where he worked with Harold Clurman, Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan and Clifford Odets. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

In 1932 Blitzstein wrote Condemned, a play about the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. The following year he married the novelist, Eva Goldbeck. Blitzstein was openly homosexual and the couple had no children. Eva introduced her husband to the work of Bertolt Brecht, a German writer who she had translated into English. Blitzstein wrote in 1935: “It is clear to me that the conception of music in society… is dying of acute anachronism; and that a fresh idea, overwhelming in its implications and promise, is taking hold. Music must have a social as well as artistic base; it should broaden its scope and reach not only the select few but the masses”. Soon afterwards he joined the American Communist Party. He also contributed to left-wing journals such as New Masses.

Eva Goldbeck died on 26th May, 1936. She had been suffering from breast cancer and anorexia nervosa. Blitzstein was shattered, and in order to escape his grief, he threw himself into his work, beginning composition of a political opera, The Cradle Will Rock, suggested to him by Bertolt Brecht some months earlier.

In 1937 Blitzstein worked with Orson Welles and John Houseman in order to put on this musical about the tyranny of capitalism. Houseman argued that Blitzstein, described as "a play with music (while others, at various times, called it an opera, a labour opera, a social cartoon, a marching song and a propagandistic tour de force)". Welles later recalled: "Marc Blitzstein was almost a saint. He was so totally and serenely convinced of the Eden which was waiting for us all the other side of the Revolution that there was no way of talking politics to him.... When he came into the room the lights got brighter. He was a an engine, a rocket, directed in one direction which was his opera - which he almost believed had only to be performed to start the Revolution."

Developed within the Federal Theatre Project, the original production of The Cradle Will Rock, with Howard da Silva and Will Geer, was banned for political reasons. It eventually was performed at the Mercury Theatre (108 performances). Another Blitzstein play, No For an Answer (1941), was also closed down because of its political content.

Brooks Atkinsonwas one of the reviewers who appreciated his work: Marc Blitzstein's in the New York Times: "If Mr. Blitzstein looks like a mild little man as he sits before his piano, his work generates current like a dynamo. He can write anything from tribal chant to tin pan alley balladry, and when he settles down to serious business at its conclusion, his music-box roars with rage and his actors frighten the aged roof of the miniature Mercury Theatre." The theatre producer, Hallie Flanagan, added: "Marc Blitzstein sat down at the piano and played, sang and acted with the hard, hypnotic drive which came to be familiar to audiences, his new opera. It took no wizardry to see that this was not just a play set to music, nor music illustrated by actors, but music and play equaling something new and better than either."

Blitzstein served in the US Air Force during the Second World War. His abilities were used as music director of the American broadcasting station in London. His ballet, The Guests, was performed in 1949. An adaptation of The Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht appeared in 1954 and ran for the next seven years on Broadway (2,611 performances). It included Blitzstein's only hit song, Mack the Knife.

Like other former members of the American Communist Party who worked in the entertainment industry, Blitzstein's name appeared in Red Channels. In 1958, Blitzstein received a subpoena to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Blitzstein admitted his membership of the Communist Party but refused either to name names, or co-operate any further. As a result he was blacklisted.

Other work included a musical, Regina (1949), based on the play, The Little Foxes, by Lillian Hellman and Juno (1959), based on Sean O'Casey's Juno and the Paycock. His biographer, Eric A. Gordon, has argued that Blitzstein was "the first theater composer to set to music the authentic American language as spoken by all social classes from immigrant laborers to society matrons."

In January 1964 Marc Blitzstein went on holiday to the island of Martinique. According to his biographer: "Late one evening, in January 1964, following a session of heavy drinking, he had picked up three Portuguese sailors. Exactly what happened next is unclear, but it seems that whilst travelling between bars, one slipped into a nearby alley with Blitzstein in response to his sexual advances. The other two followed and all three robbed him, beat him up and stripped him of all his clothes except his shirt and socks. The police found him moaning and crying in the middle of the night, and took him to a hospital. The injuries did not appear serious, but he was bleeding to death from internal contusions and he died the next evening, January 22nd, 1964."Marc Blitzstein, the son of a wealthy banker, was born in Philadelphia on 2nd March, 1905. His father was a socialist, but Blitzstein later recalled that he was "as modern in social thinking as he was conservative in musical taste". A child prodigy, he performed as a soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra when he was only fifteen. He studied at the Curtis Institute of Music and later trained with Nadia Boulanger in Paris and Arnold Schonberg in Berlin.

Blitzstein wrote plays as well as music and joined theGroup Theatre in New York City where he worked with Harold Clurman, Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan and Clifford Odets. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

In 1932 Blitzstein wrote Condemned, a play about the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. The following year he married the novelist, Eva Goldbeck. Blitzstein was openly homosexual and the couple had no children. Eva introduced her husband to the work of Bertolt Brecht, a German writer who she had translated into English. Blitzstein wrote in 1935: “It is clear to me that the conception of music in society… is dying of acute anachronism; and that a fresh idea, overwhelming in its implications and promise, is taking hold. Music must have a social as well as artistic base; it should broaden its scope and reach not only the select few but the masses”. Soon afterwards he joined the American Communist Party. He also contributed to left-wing journals such as New Masses.

Eva Goldbeck died on 26th May, 1936. She had been suffering from breast cancer and anorexia nervosa. Blitzstein was shattered, and in order to escape his grief, he threw himself into his work, beginning composition of a political opera, The Cradle Will Rock, suggested to him by Bertolt Brecht some months earlier.

In 1937 Blitzstein worked with Orson Welles and John Houseman in order to put on this musical about the tyranny of capitalism. Houseman argued that Blitzstein, described as "a play with music (while others, at various times, called it an opera, a labour opera, a social cartoon, a marching song and a propagandistic tour de force)". Welles later recalled: "Marc Blitzstein was almost a saint. He was so totally and serenely convinced of the Eden which was waiting for us all the other side of the Revolution that there was no way of talking politics to him.... When he came into the room the lights got brighter. He was a an engine, a rocket, directed in one direction which was his opera - which he almost believed had only to be performed to start the Revolution."

Developed within the Federal Theatre Project, the original production of The Cradle Will Rock, with Howard da Silva and Will Geer, was banned for political reasons. It eventually was performed at the Mercury Theatre (108 performances). Another Blitzstein play, No For an Answer (1941), was also closed down because of its political content.

Brooks Atkinson was one of the reviewers who appreciated his work: Marc Blitzstein's in the New York Times: "If Mr. Blitzstein looks like a mild little man as he sits before his piano, his work generates current like a dynamo. He can write anything from tribal chant to tin pan alley balladry, and when he settles down to serious business at its conclusion, his music-box roars with rage and his actors frighten the aged roof of the miniature Mercury Theatre." The theatre producer, Hallie Flanagan, added: "Marc Blitzstein sat down at the piano and played, sang and acted with the hard, hypnotic drive which came to be familiar to audiences, his new opera. It took no wizardry to see that this was not just a play set to music, nor music illustrated by actors, but music and play equaling something new and better than either."

Blitzstein served in the US Air Force during the Second World War. His abilities were used as music director of the American broadcasting station in London. His ballet, The Guests, was performed in 1949. An adaptation of The Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht appeared in 1954 and ran for the next seven years on Broadway (2,611 performances). It included Blitzstein's only hit song, Mack the Knife.

Like other former members of the American Communist Party who worked in the entertainment industry, Blitzstein's name appeared in Red Channels. In 1958, Blitzstein received a subpoena to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Blitzstein admitted his membership of the Communist Party but refused either to name names, or co-operate any further. As a result he was blacklisted.

Other work included a musical, Regina (1949), based on the play, The Little Foxes, by Lillian Hellman and Juno (1959), based on Sean O'Casey's Juno and the Paycock. His biographer, Eric A. Gordon, has argued that Blitzstein was "the first theater composer to set to music the authentic American language as spoken by all social classes from immigrant laborers to society matrons."

In January 1964 Marc Blitzstein went on holiday to the island of Martinique. According to his biographer: "Late one evening, in January 1964, following a session of heavy drinking, he had picked up three Portuguese sailors. Exactly what happened next is unclear, but it seems that whilst travelling between bars, one slipped into a nearby alley with Blitzstein in response to his sexual advances. The other two followed and all three robbed him, beat him up and stripped him of all his clothes except his shirt and socks. The police found him moaning and crying in the middle of the night, and took him to a hospital. The injuries did not appear serious, but he was bleeding to death from internal contusions and he died the next evening, January 22nd, 1964."

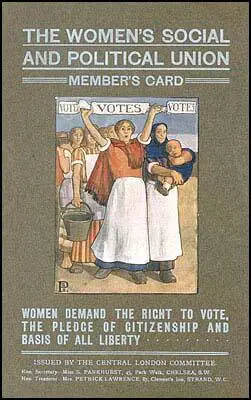

On this day in 1912 The Manchester Guardian made an attack on the Women Social & Political Union. "The madness of the militants… the small body of misguided women who profess to represent the noble and serious cause of political enfranchisement of women, but in fact do their utmost to degrade and hinder it."

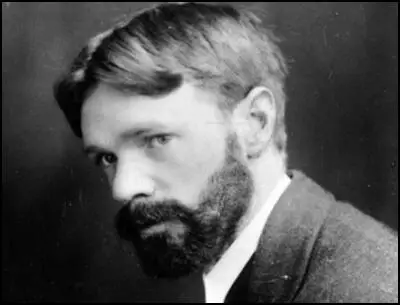

On this day in 1930 David Herbert Lawrence died. Lawrence, the fourth of the five children of Arthur John Lawrence (1846–1924), a miner, was born in Eastwood near Nottingham on 11th September, 1885. His father was barely literate, but his mother, Lydia Lawrence, was better educated and was determined that David and his brothers should not become miners.

According to his biographer, John Worthen: "Arthur Lawrence, like his three brothers, was a coalminer who worked from the age of ten until he was sixty-six, was very much at home in the small mining town, and was widely regarded as an excellent workman and cheerful companion. Lawrence's mother Lydia was the second daughter of Robert Beardsall and his wife, Lydia Newton of Sneinton; originally lower middle-class, the Beardsalls had suffered financial disaster in the 1860s and Lydia, in spite of attempts to work as a pupil teacher, had, like her sisters, been forced into employment as a sweated home worker in the lace industry. But she had had more education than her husband, and passed on to her children an enduring love of books, a religious faith, and a commitment to self-improvement, as well as a profound desire to move out of the working class in which she felt herself trapped."

As a child Lawrence preferred the company of girls to boys and this led to him being bullied at school. He was an intelligent boy and at the age of 12 he became the first boy from Eastwood to win one of the recently established county council scholarships, and went to Nottingham High School. However, he did not get on with the other boys and left school in the summer of 1901 without qualifications.

Lawrence started work as a factory clerk for a surgical appliances manufacturer in Nottingham. Soon afterwards, his eldest brother, William Ernest Lawrence, by now a successful clerk in London, fell ill and died on 11th October 1901. Lydia Lawrence was distraught with the loss of her favourite son and now turned her attention to the career of David. John Worthen argues that "she needed her children to make up for the disappointments of her life." David now gave up his employment as a clerk and started work as a pupil teacher at the school in Eastwood for miner's children.

Lawrence became friendly with Jessie Chambers. Her sister, Ann Chambers Howard, has argued: "They spent a great deal of time together working and reading, walking through the fields and woods, talking and discussing. Jessie was interested in everything, to such a degree that her intensity of perception almost amounted to a form of worship. She felt that her own appreciation of beauty, of poetry, of people, and of her own sorrows amounted to something far greater than anyone else had ever experienced. Her depth of felling was a great stimulation to Lawrence, who with his naturally sensitive mind was roused to critical and creative consciousness by her." Together they developed an interest in literature. This included reading books together and discussing authors and writing. It was under Jessie's influence that in 1905 Lawrence started to write poetry. Lawrence later admitted that Jessie was "the anvil on which I hammered myself out." The following year he began work on his first novel, The White Peacock.

Lawrence's mother wanted him to continue his education and in 1906 he began studying for his teacher's certificate at the University College of Nottingham. In 1908 Lawrence qualified as a teacher and found employment at Davidson Road School in Croydon. According to the author of D. H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider (2005): "He found the demands of teaching in a large school in a poor area very different from those at Eastwood under a protective headmaster. Nevertheless he established himself as an energetic teacher, ready to use new teaching methods (Shakespeare lessons became practical drama classes, for example)."

In 1909 Jessie Chambers sent some of Lawrence's poems to Ford Madox Ford, the editor of The English Review. Ford was greatly impressed with the poems and arranged a meeting with Lawrence. After reading the manuscript of The White Peacock, wrote to the publisher William Heinemann recommending it. Ford also encouraged Lawrence to write about his mining background.

While living in Croydon Lawrence became friendly with a fellow schoolteacher, Helen Corke, who had recently had an affair with a married man who killed himself. She told Lawrence the story, and showed him her manuscript, The Freshwater Diary. Lawrence used this material for his next novel, The Trespasser.

Lawrence also began work on the autobiographical novel, Sons and Lovers. He sent the first-drafts of the novel to Jessie Chambers. As her sister, Ann Chambers Howard points out: "The ruthless streak in his nature now began to emerge and halfway through the book Jessie became increasingly alarmed and bewildered by his cruel treatment of people whom they knew. He began to include people, episodes and attitudes which were quite foreign to their nature and to their previous behaviour and experience.... My father remembered watching her as she read the manuscripts, writing her comments carefully at the side before sending them back to him. Lawrence rejected her advice completely, insisting on including all the things which she had begged him to alter or omit. He continued to send her the manuscripts, asking for advice which she in her anguish repeatedly gave, only to be continually ignored." Eventually she refused to answer Lawrence's letters and their relationship came to an end.

In August 1910, Lydia Lawrence became ill with cancer. Lawrence visited his mother in Eastwood every other weekend. In October he realised she was close to death and he decided to stay at home to nurse her. He wrote to a friend: "There has been this kind of bond between me and my mother... We knew each other by instinct... We have been like one, so sensitive to each other that we never needed words. It has been rather terrible and has made me, in some respects, abnormal." His mother died on 9th December 1910. Soon afterwards Lawrence had got engaged to his old college friend Louie Burrows.

In January 1911, Lawrence's first novel, The White Peacock, was published. However, his writing was not going well. Without the advice of Jessie Chambers, he found it difficult to continue with Sons and Lovers. His health was poor and after falling seriously ill with pneumonia he decided to abandon his teaching career. After convalescence in Bournemouth, he rewrote The Trespasser.

Lawrence broke off his engagement to Louie Burrows, and returned to Nottingham. On 3rd March 1912, Lawrence went to see Ernest Weekley, who taught him while he was at the University College of Nottingham. During the visit he met his much younger wife, Frieda von Richthofen. Lawrence fell in love with Frieda and in May 1912 managed to persuade her to leave her husband and three young children. However, as John Worthen has pointed out: "Frieda's desire to be free of her marriage was not consistent with Lawrence's insistence that she become his partner, and she suffered agonies from the loss of her children (Weekley was determined to keep them away from her)."

Claire Tomalin has argued: "She (Frieda) gave him what he most wanted at the time they met, being probably the first woman who positively wanted to go to bed with him without guilt or inhibition; she was not only older, and married, but bored with her husband, and had been encouraged to believe in the therapeutic power of sex by an earlier lover, one of Freud's disciples. Lawrence was bowled over by this... Whether her decision to throw in her lot permanently with Lawrence contributed positively to his development as a writer is at least open to question. There could have been a different story, in which Lawrence married someone like the intelligent Louie; in which he settled in England and lived a quiet, healthy - and longer - life, cherished by his wife and family; in which his novels continued more in the pattern of Sons and Lovers and The Rainbow, social and psychological studies of the country and people he knew best."

Lawrence set-up home with Frieda in Icking, near Munich. Lawrence claimed "the one possible woman for me, for I must have opposition - something to fight". The author of D. H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider has argued: "He cooked, cleaned, wrote, argued; Frieda attended little to house keeping (though washing became her specialty), but she could always hold her own against his theorizing, and maintained her independence of outlook as well as of sexual inclination (she slept with a number of other men during her time with Lawrence)." While living in Germany he finished his autobiographical novel Sons and Lovers. His publisher, Heinemann turned down the novel on grounds of indecency. He sent it to his friend, Edward Garnett, who read manuscripts for Gerald Duckworth and Company. The novel was accepted and published in May 1913. It received some good reviews but sold poorly.

In 1914 the couple returned to England. Lawrence's novel brought him to the attention of Edward Marsh. He introduced Lawrence to Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry. They were witnesses to Lawrence's marriage to Frieda. Claire Tomalin has pointed out: "The men put on formal three-piece suits, Frieda enveloped herself in flowing silks and Katherine wore a sombre suit." Lawrence wrote to a friend: "I don't feel a changed man, but I suppose I am one."

The two couples established themselves in two cottages near Chesham in Buckinghamshire. Later, Mansfield and Murry joined the Lawrences at Higher Tregerthen, near Zennor, in an attempt at communal living. It was a failure and within weeks she and Murry moved on.

On the outbreak of the First World War the authorities became concerned that Frieda von Richthofen was a spy. Local people reported that the Lawrences were using the clothes hanging on their washing line to send coded messages to German U-boats. After searching their cottage, the authorities forced the Lawrences to leave the area.

Lawrence began spending time with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell at their home Garsington Manor near Oxford. It was also a refuge for conscientious objectors. They worked on the property's farm as a way of escaping prosecution. It also became a meeting place for a group of intellectuals described as the Bloomsbury Group. Members included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, David Garnett, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley. Other people who Lawrence met at Garsington included Dorothy Brett, Mark Gertler, Siegfried Sassoon, Aldous Huxley, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

The Rainbow was published in September 1915. According to Claire Tomalin: "Katherine Mansfield's reminiscences of New Zealand probably inspired Lawrence with the lesbian episode in The Rainbow, and she was certainly the model for Gudrun in Women in Love." It received hostile reviews that concentrated on the way Lawrence dealt with sexual themes. Robert Wilson Lynd in The Daily News said the book was "windy, tedious, boring and nauseating". Lynd, and another critic, Clement King Shorter, condemned the lesbian episode in the book. Another reviewer argued that the book "betrayed the young men" fighting on the Western Front.

At Bow Street Magistrates' Court on 13th November the novel was banned as obscene. As John Worthen has pointed out: "Its religious language, emotional and sexual explorations of experience, and sheer length had given its readers problems, but it was Ursula's lesbian encounter with a schoolteacher in the chapter Shame which had finally condemned it in the eyes of the law and of a country now focused on conflict."

In the autumn of 1915 Lawrence had joined forces with Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry to establish a new magazine called The Signature. Claire Tomalin, the author of Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (1987) has argued that it was decided "to sell by subscription; it was to be printed in the East End, and the contributors were to have a club room in Bloomsbury for regular meetings and discussions." Sales were poor and the magazine folded after three issues.

Ottoline Morrell helped Lawrence with his writing by supporting him emotionally and financially. In December 1916 he showed her his unpublished novel, Women in Love. On reading it she was extremely upset at the unflattering portrayal of herself that was thinly disguised in the character of Hermione Roddice. Philip Morrell went to Lawrence's agent and threatened to bring legal action against any publisher who brought out the book.

Lawrence, who was opposed to the war, was twice called up for military service but was rejected on health grounds. The couple went to live in a cottage at Pulborough. Later they were joined by John Middleton Murry when Katherine Mansfield suffering from tuberculosis, had moved to Bandol on the south coast of France.

Lawrence caught influenza during the pandemic in November 1918, and once again he nearly died. It was not until a year later that he was fit enough to leave England. At first he lived in Florence but after Frieda Lawrence joined him after her visit to her family in Germany, they settled temporarily in Picinisco, in the Abruzzi Mountains, before moving on to Capri, where the English writing colony, including Compton Mackenzie, W and Francis Brett Young. In February 1920, they moved to Sicily, where they stayed for the next two years.

In 1920 Martin Secker agreed to publish Women in Love, a sequel to his earlier novel The Rainbow, and follows the continuing loves and lives of the Brangwen sisters, Gudrun and Ursula. Once again the sexual content of the book caused controversy. over its sexual subject matter. W. Charles Pilley in the John Bull Magazine, said: "I do not claim to be a literary critic, but I know dirt when I smell it, and here is dirt in heaps - festering, putrid heaps which smell to high Heaven." Even his friend, John Middleton Murry, wrote in the The Athenaeum that Lawrence was "far gone in the maelstrom of his sexual obsession" and that the novel was "sub-human and bestial."

In January 1921 Lawrence and Frieda visited Sardinia and he wrote the travel book, Sea and Sardinia. He also completed his next book Aaron's Rod, a novel in which Aaron Sisson, is a union official in the coal mines, decides to leave his wife and family, and move to Florence, where he attempts to make a living as a musician. In order for it to be published, Martin Secker, heavily censored the passages describing Aaron's sexual experiences.

This time John Middleton Murry liked the book describing it as "the most important thing that has happened to English literature since the war". The author of D. H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider argues that "to most reviewers, however, it was simply another interesting book made rather unpleasant by Lawrence's obsession with sex." Richard Rees has argued: "If Lawrence was the one great original genius of English literature in my time, Murry was the one critic with the necessary combination of gifts for coping with him, and Lawrence was aware of this, off and on. In the process Murry sometimes made mistakes and sometimes made himself ridiculous. But how can anyone fail to see that this was inevitable in the circumstances?"

Over the next few months Lawrence's revised his short novels, The Fox, The Captain's Doll, and The Ladybird. He also wrote ten short stories with a First World War background that appeared in the collection, England, my England and Other Stories (1922). According to John Worthen the stories were "a way of coming to terms with the past, and putting it behind him".

In February 1922 Lawrence and Frieda decided to travel to Ceylon. He found the country too hot for writing and moved onto Australia. Settling at Thirroul, 69 km south of Sydney, Lawrence wrote his novel Kangaroo, in six weeks. The book tells the story of an English writer, Richard Lovat Somers, and his German wife Harriet. This appears to be semi-autobiographical and is based on the time he spent in New South Wales. "Kangaroo" is the nickname of one of Lawrence's characters, Benjamin Cooley, the leader of a secretive, fascist paramilitary organisation. It has been argued that Cooley was based on Major General Charles Rosenthal, a notable right wing activist in the early 1920s.

Lawrence and Frieda visited North America and while in Santa Fe, developed a close friendship with the poet, Witter Bynner and his lover, Willard Johnson. Bynner took the Lawrences to Taos in New Mexico to see a local Apache reservation. Lawrence also met Mabel Dodge Luhan and later these characters are portrayed in his novel The Plumed Serpent (1926).

Lawrence returned to England for a brief holiday and having invited his London friends to dinner at the Café Royal, he encouraged them to come back to New Mexico with him and Frieda where he was "committed to... establishing a new life on earth". Only John Middleton Murry and Dorothy Brett were the only ones to accept the offer. However, Middleton Murry changed his mind at the last moment. In March, 1924, the three left for North America and with the help of Mabel Dodge Luhan they established a small community at Taos.

In March 1925, D. H. Lawrence went down with a combination of typhoid and pneumonia, and nearly died. The doctor also diagnosed tuberculosis. Lawrence and Frieda had planned to return to England, but the doctor advised altitude, and they made their way back up to the ranch. Lawrence recorded that "New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had." However, for the sake of his health it was decided to move back to Italy. This time they stayed in Spotorno with Angelo Ravagli. Frieda's daughters also lived with them for a while. He used these experiences to write his short novel The Virgin and the Gipsy. Frieda began an affair with Ravagli, who later claimed that Lawrence discovered them "flagrante delicto". Lawrence's biographer argued that he responded by having an affair with Dorothy Brett while she was on holiday in Italy.

In 1926 he visited Nottingham. This inspired him to begin a new novel, Lady Chatterley's Lover. Lawrence's biographer, John Worthen, has argued: "His sympathy was now far more with his father (who had died in 1924) than with his mother, and the novel's central character was thoroughly working-class. The second version, started in November 1926, made the novel sexually explicit; it became a hymn to the love-making of the couple, to the body of the man and the woman, for sexuality as it could potentially be between an independent working-class man and an independent upper-class woman. It was a final fictional reworking of a theme which he had always written about for the chance it gave him to concentrate on sexual attraction (and to some extent had enacted in his own life and relationships), but which he now returned to both polemically and nostalgically."

The highly explicit sex passages in the book meant that Lawrence was unable to find a publisher for the novel. With the help of the Italian bookseller Pino Orioli, Lawrence arranged for Lady Chatterley's Lover to be printed in and distributed from Florence. The book made him so much money that he could now afford to live in expensive hotels. Later he moved to Bandol on the south coast of France.

Lawrence gave up writing fiction but he continued to write poems and newspaper articles. In 1929 the police seized the unexpurgated typescript of his volume of poems Pansies. An exhibition of his paintings in London that summer was raided by the police, and court hearings were necessary before the paintings could be returned to their owner.

In February 1930, D. H. Lawrence went into the Ad Astra Sanatorium in Vence, where he was visited by friends from England, including H. G. Wells and Aldous Huxley. He discharged himself from the sanatorium on 1st March, and Frieda Lawrence helped him move into the Villa Robermond, a rented house in the town. He died the following day and was buried in the local cemetery on 4th March.

Soon after his death, the novelist Ethel Mannin, wrote: "D. H. Lawrence turned his back in disgust on civilization as we know it and attempted to find uncorrupted life in the Mexican wildernesses. Since his death various little people have written patronizing little articles about him pointing to his limitations, regardless of the fact that in his limitations he was infinitely greater than any of them in their fulfilments. His preoccupation with sex was a preoccupation with life."

On this day in 1961 Norah Dacre Fox died at Middlesex Hospital.

Norah Doherty, one of nine children of John and Charlotte Doherty, was born in Dublin in 1878. Her father was an Irish protestant and in 1891 the family decided to emigrate to England and they eventually decided to settle in Teddington.

In 1909 she married Charles Richard Dacre Fox. She was interested in the subject of women's suffrage and in 1912 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). According to Elizabeth Crawford she was particularly close to Grace Roe, who at that time held a senior place in the movement.

It has been argued by the authors of Mosley's Old Suffragette (2010) that her remarkable rhetorical skill allowed her to rise quickly through the WSPU ranks to become, by March 1913, its General Secretary. In this role she led the "campaign against forcible feeding, concentrating particularly on attempts to persuade Church of England bishops to denounce the practice." Jessie Stephen has argued: "Mrs Dacre Fox became prominent (in the leadership of the WSPU) toward the end... because she was a very good speaker - a fine speaker - and very effective too."

In May 1914 Norah Dacre Fox was arrested with Flora Drummond during a demonstration. The Times reported that the two women "openly and deliberately advocating acts of militancy and violence." While in Holloway Prison she went on hunger-and-thirst strike and was released on licence.

Nora Dacre Fox was involved in the production of The Suffragette, the WSPU newspaper. Emmeline Pankhurst later recalled: "The Government made several last, desperate efforts to crush the WSPU to remove all the leaders and to destroy our paper, The Suffragette. They issued summonses against Mrs. Drummond, Mrs. Dacre Fox, and Miss Grace Roe; they raided our headquarters at Lincoln's Inn House; twice they raided other headquarters temporarily in use; not to speak of raids made upon private dwellings where the new leaders, who had risen to take the places of those arrested, were at their work for the organisation."

On 30th July 1914 she was arrested at Buckingham Palace while attempting to present a letter from Mrs Pankhurst to King George V. According to Julie V. Gottlieb this resulted in her "thrice being imprisoned in Holloway for militant acts, and she had gone on hunger strike for which she received a medal with three bars from the leaders of the WSPU."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The leadership of the WSPU immediately began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, Norah Dacre Fox helped the WSPU organise a demonstration in London. A former member of the WSPU, Jessie Stephen, who resigned over the issue of the First World War, argued that "Dacre Fox and the Pankhursts" were members of a "close cadre of middle and upper class conservative women leading the WSPU" after the outbreak of war.

Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

During the autumn of 1915, Norah Dacre Fox, Emmeline Pankhurst, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Grace Roe, went on a lecture tour of South Wales, the Midlands and Scotland in an attempt to encourage trade unions to support war work. According to the authors of Mosley's Old Suffragette (2010): "By October 1915 the rightward swing in the political view of the Pankhursts and the WSPU was becoming very evident... They focused on criticizing Germany and all Germans who were living and working in England, particularly in the higher echelons of the civil service. This particular campaign was to occupy Norah intensely."

On 14th August 1918, The Times reported that: "Mrs Dacre Fox said... we had to make a clean sweep of all persons of German blood, without distinction of sex, birthplace, or nationality. Never had the time been so ripe for action; never would it be so favourable again. If we allowed the opportunity to pass now, German influence, which at the present moment was hampering and hindering the War Cabinet in its prosecution of the war, would become more firmly entrenched than ever in this country.... Any person in this country, no matter who he was or what his position, who was suspected of protecting German influence, should be tried as a traitor, and, if necessary, shot. There must be no compromise and no discrimination."

In the 1918 General Election she stood as an independent candidate in the Richmond constituency. During the campaign she argued that people of German birth should be deported from the country. She later recalled that "my own distrust of party politics made me chary of turning in this direction, and I preferred to stand as an Independent, going down with all other women candidates on this occasion, save one." Norah Dacre Fox won only 3,615 votes in the election.

Norah Dacre Fox campaigned against the Treaty of Versailles. In a letter to The Times on 10th April 1920 she argued: "France is our friend. Upon her security and her prestige depend the security and prestige of the British Empire. One had imagined that this lesson had been fully learnt as the experience of the European War, and a policy which tends to weaken France must be a policy which helps to strengthen her enemy and ours - Germany. The truth is that in this country there are a group of politicians and public men, surrounded by officials and advisers, who have always worked and are still working for a rapprochement with Germany and the hope of a future alliance with her."

After the war Norah Dacre Fox went to live with Dudley Elam at his home in Northchapel, near Chichester. Elam, was already married to another woman, and so she added "Elam" to her name by deed poll. On 29th May she gave birth to a son. According to Elizabeth Crawford: Having little interest in motherhood, arranged for a nanny to bring up her son. He was 9 years old before he realised that she was his mother."

Norah Elam now joined Flora Drummond and Elsie Bowerman to establish the Women's Guild of Empire, a right wing league opposed to communism. Drummond's biographer, Krista Cowman, pointed out: "When the war ended she was one of the few former suffragettes who attempted to continue the popular, jingoistic campaigning which the WSPU had followed from 1914 to 1918.... She founded the Women's Guild of Empire, an organization aimed at furthering a sense of patriotism in working-class women and defeating such socialist manifestations as strikes and lock-outs." She was also active in the Anti-Vivisection Society.

Norah was an active member of the Conservative Party until she defected to the British Union of Fascist (BUF) in 1934. Her husband became an unpaid receptionist at the BUF's National Headquarters whereas Norah became the BUF County Women's Officer for West Sussex. She was also a regular contributor to BUF publications for the next six years.

In April 1934 Norah Elam shared a platform with William Joyce, the Director of Research and Director of Propaganda, at Chichester. As the the authors of Mosley's Old Suffragette (2010) have pointed out: "With Joyce as Area Administrative Officer, Dudley as Sub-Branch Officer for Worthing and Norah as Sussex Women's Organizer, West Sussex became a hub of fascist activity."

On 17th August 1934, The Blackshirt reported: "Mrs Dudley Elam, Area Organiser for Sussex and Hampshire held a very successful meeting at Littlehampton, addressing a crowd of over 100 people. She spoke for about an hour and gave a clear and lucid exposition of Fascist policy notwithstanding a certain amount of heckling from the Communist element in the audience."

Norah attended a meeting with William Joyce and Oswald Mosley at the Pier Pavilion in Worthing, on 9th October 1934. Members of the British Union of Fascists became involved in violent clashes with protestors and Joyce and Mosley were arrested. At their trial Norah gave evidence that the trouble was caused by anti-fascist demonstrators. Another witness claimed that she heard people chanting: "One! Two! Three! Four! Five! We want Mosley, dead or alive!"

It was not long before Norah became very close to Oswald Mosley. The author of Femine Fascism: Women in Britain's Fascist Movement (2003) has pointed out: "Elam's status in the BUF and the sensitive tasks with which she was entrusted offer some substance to the BUF's claim to respect sexual equality. While, in principle, the movement was segregated by gender and women in positions of leadership were meant to have authority only over other women. Elam was quite evidently admitted to Mosley's inner circle."

Norah became so convinced by the merits of Adolf Hitler that she sent her 12 year old son to live in Nazi Germany. He joined the Hitler Youth and the authors of Mosley's Old Suffragette (2010) have commented: "He attended various demonstrations and was shown how to roll marbles under police horses' hooves to cause maximum damage, disruption and pain; he recalled Jew-baiting incidents with delight."

Norah became involved in a dispute with Flora Drummond who had criticised the violent methods of the British Union of Fascists. On 22nd February 1935 Norah argued in The Blackshirt that Drummond had once "defied all law and order; smashed not only windows, but all the meetings of Cabinet Ministers on which she could lay hands, and was for long the daily terror of the Public Prosecutor and the despair of Bow Street!" Norah described Drummond and other former suffragettes as "extinct volcanoes either wandering about in the backwoods of international pacifism and decadence, or prostrating themselves before the various political parties." Later she wrote: "From those days of heroic struggle seems now a far cry. But will anyone deny that in all the long history of human effort and sublime self-sacrifice which the world has seen a greater disillusionment can be found than the complete failure of the women's movement in the post-war years?"

In November 1936 Norah Elam was one of ten women the British Union of Fascists announced would be candidates in the next general election. Elam was selected to fight the Northampton constituency. Mosley used Norah's past as one of the leaders of the Women's Social and Political Union to counter the criticism that the BUF was anti-feminist. In one speech Norah Elam argued that her prospective candidacy for the House of Commons "killed for all time the suggestion that National Socialism proposed putting British women back in the home". On another occasion she claimed: "No woman who loves her country, her sex or her liberty, need fear the coming victory of Fascism. Rather she will find that what the suffragettes dreamt about twenty odd years ago is now becoming a possibility, and women will buckle on her armour for the last phase of the greatest struggle, for the liberation of the human race, which the world has yet seen."

The outbreak of the Second World War reduced support for the British Union of Fascists. However, Norah Elam remained committed to the cause and became a secret member of the Right Club. Formed by Archibald Ramsay in 1939, it was an attempt to unify all the different right-wing groups in Britain. Ramsay argued: "The main object of the Right Club was to oppose and expose the activities of Organized Jewry, in the light of the evidence which came into my possession in 1938. Our first objective was to clear the Conservative Party of Jewish influence, and the character of our membership and meetings were strictly in keeping with this objective."

Other members of the Right Club included William Joyce, Anna Wolkoff, Joan Miller, A. K. Chesterton, Francis Yeats-Brown, E. H. Cole, Lord Redesdale, 5th Duke of Wellington, Duke of Westminster, Aubrey Lees, John Stourton, Thomas Hunter, Samuel Chapman, Ernest Bennett, Charles Kerr, John MacKie, James Edmondson, Mavis Tate, Marquess of Graham, Margaret Bothamley and Lord Sempill.

On 18th December 1939, the police raided Norah Elam's flat where they found documents suggesting that she had been taking part in secret meetings of right-wing groups. A letter from Oswald Mosley stated that "Mrs Elam had his full confidence, and was entitled to do what she thought fit in the interests of the movement on her own responsibility." On 23rd January 1940, Norah was arrested and interrogated him in order to establish whether her handling of BUF funds had been illegal or improper.

A MI5 report suggested that it was suspicious that Norah Elam had been placed in charge of BUF funds. Mosley told Special Branch detectives: "As regards the money paid to Mrs Elam we have nothing to be ashamed of and nothing to conceal. When war became imminent we had to be prepared for any eventually. There might have been an air raid, our headquarters might have been smashed by a mob, I myself was expecting to be assassinated. I may tell you quite frankly that I took certain precautions. It was necessary then for us to disperse the funds in case anything should happen to headquarters or the leaders. Mrs. Elam therefore took charge of part of our funds for a short period before and after the declaration of war. There was nothing illegal or improper about this."

On 22nd May 1940 the British government announced the imposition of Defence Regulation 18B. This legislation gave the Home Secretary the right to imprison without trial anybody he believed likely to "endanger the safety of the realm". The following day, Norah Elam, Mosley, and other leaders of the BUF were arrested. On the 30th May the BUF was dissolved and its publications were banned. On 6th June Action Magazine recorded: "Mrs Elam (Mrs Dacre Fox) a militant suffragette and ardent patriot was arrested with three other women, Mrs Whinfield, Mrs Brock-Griggs and Olive Hawks."

Elam was sent to Holloway Prison with Diana Mosley. A fellow prisoner, Louise Irving, recorded: "I met Mrs Elam when I was in F. Wing in Holloway. I was a little in awe of her - she was of course a much older woman, and highly intelligent and erudite. Lady Mosley sometimes invited me to her cell with a few others for a small friendly get-together. All sorts of topics - art, music, literature etc were discussed, and Mrs Elam was invariably there... I was never close enough to her to hear about her suffragette experiences, but she was certainly a staunch member of BUF."

In November 1943, Herbert Morrison controversially decided to order the release of British Union of Fascists members from prison. There were large-scale protests and even Diana's sister, Jessica Mitford, described the decision as "a slap in the face of anti-fascists in every country and a direct betrayal of those who have died for the cause of anti-fascism."

After the war Norah Dacre Fox remained in contact with Mary Allen and Arnold Leese, who was an extreme anti-Semite, who broke away from Oswald Mosley because he believed he was "soft on Jews". Although she never saw her again, Nora kept a signed photograph of Diana Mosley in her bedroom. 1863. Goodison Park.