Spartacus Blog

What are the political lessons to learn from the Peterloo Massacre?

Over the last few days the media has recognised the 200 year anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre. In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society (MPUS), an organization that demanded parliamentary representation for the rapidly growing industrial city of Manchester, which had no MP at the time. The MPUS invited two well-known reformers, Henry Orator Hunt and Richard Carlile, to address a meeting to be held at St. Peter's Field on the subject of parliamentary reform. A local woman, Mary Fildes, was also invited to talk on the subject of female suffrage. (1)

Although there was no trouble the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but William Hulton, the chairman of the local magistrates came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in the area at midday. The magistrates decided to arrange for a large number of soldiers to be in Manchester on the day of the meeting. This included four squadrons of cavalry of the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), a detachment of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (120 men) and all Manchester's special constables (400 men). (2)

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest the other leaders of the demonstration who were now assembled on the platform. Nadin replied that this could not be done without the help of the military. Lieutenant Colonel George L'Estrange, the commander of the military forces in Manchester and Major Thomas Trafford, the commander of the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry, chose Captain Hugh Birley to carry out the order. Local eyewitnesses claimed that most of the sixty men who Birley led into St. Peter's Field were drunk. Birley later insisted that the troop's erratic behaviour was caused by the horses being afraid of the crowd. (3)

As the soldiers moved closer to the hustings, members of the crowd began to link arms to stop them arresting Henry Hunt and the other leaders. Others attempted to close the pathway that had been created by the special constables. Some of the yeomanry now began to use their sabres to cut their way through the crowd. When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they arrested Henry Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson, George Swift, John Saxton, John Tyas, John Moorhouse and Robert Wild. As well as the speakers and the organisers of the meeting, Birley also arrested the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor, the man who later established the Manchester Guardian, reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks." (4)

Samuel Bamford was another one in the crowd who witnessed the attack on the crowd: "The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads... On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled... A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises. In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again." (5)

Lieutenant Colonel George L'Estrange reported to William Hulton at 1.50 p.m. When he asked Hulton what was happening he replied: "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry? Disperse them." L'Estrange now ordered Lieutenant William Jolliffe and the 15th Hussars to rescue the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry. By 2.00 p.m. the soldiers had cleared most of the crowd from St. Peter's Field. In the process, 18 people were killed and about 500, including 100 women, were wounded. (6)

Political Interpretations of the Peterloo Massacre

As Richard J. Evans has pointed out: "The bicentenary of Peterloo is being marked in many ways, including a major film by Mike Leigh, radio and television programmes, books, exhibitions, songs, and more besides. However, not everyone has considered the event worth commemorating in such style. Paradoxically, given its own reporter’s work (John Tyas) (a 10,000-word dispatch) was followed by a thunderous denunciation of the behaviour of the troops in a leading article, The Times has chosen to cast doubt on Peterloo’s significance." (7)

In a recent editorial in The Times, it took the opportunity to argue that the left's interpretation of the Peterloo Massacre is Marxist. It also criticised Percy Bysshe Shelley and his poem, The Mask of Anarchy, for suggesting that the massacre was the result of "class politics". It also condemned E. P. Thompson for his book, Making of the English Working Class (1963) and suggested that he put together “wholly disconnected movements"– including the one that led to Peterloo – to form a misleading narrative that took an “isolated outrage” out of context. "Politicians such as Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn have since, with a ropey grasp of history, added further anachronisms to the mix, such as the Levellers and the Tolpuddle Martyrs." Surely, it suggests, such protests were unnecessary, given the fact that parliamentary reform acts eventually brought universal suffrage “without recourse to the revolution that governments had feared since 1789”. It went on to argue a "modern myth” was "created that had no basis in fact". Finally, it complained about the BBC’s decision to broadcast “no fewer than 10 radio programmes on the massacre”, and disputed the framing of a Radio 4 documentary entitled Peterloo: The Massacre That Changed Britain. (8)

This was very similar to the article published in The Daily Telegraph on the 150th anniversary of Peterloo: "Be sure the Leftist legend of Peterloo will last a long time yet in undiminished vigour for all that any disobedient historian can do. This is not to say that the legend is wholly false that no poor under-nourished working men bled and died in St Petersfields, that the yeomanry at Peterloo were all enlightened Tory philosophers and the demonstrators all envious and deceitful radical mischief makers. That would be as absurd as the received account. History is not simple. But it can be made to seem simple for purposes of propaganda - which to us now means Left-wing propaganda. That is one reason, perhaps the main reason why we celebrate the anniversary of Peterloo tomorrow." (9)

In August 2018, the Conservative peer, Daniel Finkelstein, had attacked the film director, Mike Leigh, for suggesting that Peterloo was “a major, major event” and ought to be a compulsory part of the national curriculum. Peterloo, said Finkelstein, “was not the beginning of anything much”. Britain’s modern history, moreover, "was shaped in factories and parliament and not on the street". He went on: "Mike Leigh is arguing that because all pupils are taught about 1066, the Magna Carta, the wives of Henry VIII, the French Revolution and Waterloo they should all learn about Peterloo. And this equivalence is simply wrong." He added that the "massacre of August 1829 was an outrage but treating it is a key turning point in British history is a distortion". Finkelstein believes that the left have “a romantic desire to suggest that Britain’s path was decided by street protest and a contemporary hint that it might work again can’t be allowed to make Peterloo bear more weight than it can carry”. (10)

In the editorial in The Times published on 3rd August 2019, it claimed that using the past "as a prism through which to interpret current politics is bad history". That of course depends on how you use the information. For example, in the same article it used Peterloo to condemn the exercise of "street protest" in the present day. It has always been important for conservatives to communicate the idea that the vote was given to the people because they waited patiently without protest until they received it as a present from the ruling elite. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact it was not until a 100 years later that all working-class men received the vote. Women had to wait another ten years before they got the same rights as men. Why did it take so long? Why were the ruling class so hostile to the idea of people having the opportunity to decide who should represent them in Parliament? Is it true that they did not have to take to the streets to gain these rights?

The Six Acts

To understand the importance of the Peterloo Massacre we need to have to consider is the way that the government responded to this terrible tragedy. The first move was to release John Tyas of The Times, without charge. This was an attempt to get the mainstream media to support its proposed strategy. This was in direct contrast to the way the demonstrators were treated. In the first trial of those people who attended the meeting at St. Peter's Field, the judge commented: "Some of you reformers ought to be hanged, and some of you are sure to be hanged - the rope is already round your necks." (11)

Henry Orator Hunt, was sentenced to two and a half years imprisonment in Ilchester Gaol. The other main speaker, Richard Carlile, initially escaped arrest and wrote an article on the massacre in the next edition of The Republican. Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to three years in Dorchester Gaol. (12)

The authorities also disapproved of Carlile publishing books by Tom Paine, including The Rights of Man and Age of Reason, in sections in pamphlet form. Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated. Carlile was determined not to be silenced. While he was in prison he continued to write material for The Republican, which was now being published by his wife. Due to the publicity created by Carlile's trial, the circulation of the newspaper increased dramatically and was now outselling pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (13)

The government was greatly concerned by the dangers of the parliamentary reform movement and welcomed the action taken by the Manchester magistrates at St. Peter's Field. The Prince of Wales, the future King George IV, sent a message to the magistrates thanking them "for their prompt, decisive, and efficient measures for the preservation of the public peace". (14)

Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, sent a letter of congratulations to the Manchester magistrates for the action they had taken. He also sent a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action. This was supported by John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, who was of the clear opinion" that the meeting "was an overt act of treason". (15)

As Terry Eagleton has pointed out the "liberal state is neutral between capitalism and its critics until the critics look like they're winning." (16) When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was "curbing radical journals and meetings as well as the danger of armed insurrection". (17)

(i) Training Prevention Act: A measure which made any person attending a gathering for the purpose of training or drilling liable to arrest. People found guilty of this offence could be transported for seven years.

(ii) Seizure of Arms Act: A measure that gave power to local magistrates to search any property or person for arms.

(iii) Seditious Meetings Prevention Act: A measure which prohibited the holding of public meetings of more than fifty people without the consent of a sheriff or magistrate.

(iv) The Misdemeanours Act: A measure that attempted to reduce the delay in the administration of justice.

(v) The Blasphemous and Seditious Libels Act: A measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious.

(vi) Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act: A measure which subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty. (18)

The government also decided to take action against others calling for parliamentary reform. John Stafford, who worked at the Home Office, recruited George Edwards, to spy on a group of men who were committed to creating a society based on the ideas of Thomas Spence. (19) At one meeting Edwards reported that Arthur Thistlewood said: "High Treason was committed against the people at Manchester. I resolved that the lives of the instigators of massacre should atone for the souls of murdered innocents." (20)

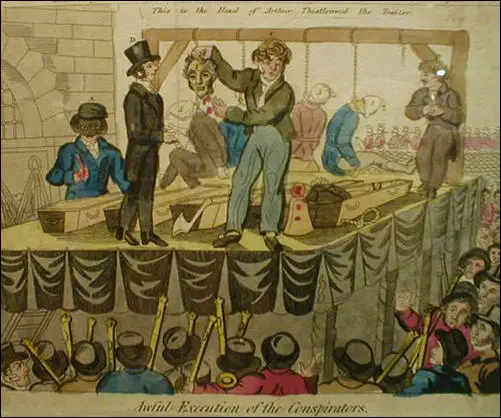

On 23rd February, 1820 Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt were arrested and the following month the men were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. Five other men were also found guilty but their original sentence of execution was subsequently commuted to transportation for life. (21) Thistlewood, Davidson, Ings, Tidd and Brunt were taken to Newgate Prison on 1st May, 1820. John Hobhouse attended the execution: "The men died like heroes. Ings, perhaps, was too obstreperous in singing Death or Liberty" and records Thistlewood as saying, "Be quiet, Ings; we can die without all this noise." (22)

Conservative newspapers promote the idea that parliamentary reform was achieved without the people resorting to violence is a myth. This is not true, in fact, a large number of men and women lost their lives in the fight for universal suffrage. Between 1770 and 1830, the Tories were the dominant force in the House of Commons. The Tories were strongly opposed to increasing the number of people who could vote. However, in November, 1830, Earl Grey, a Whig, became Prime Minister. Grey explained to William IV that he wanted to introduce proposals that would get rid of some of the rotten boroughs and pocket boroughs. Grey also planned to give Britain's fast growing industrial towns such as Manchester, Birmingham, Bradford and Leeds, representation in the House of Commons. (22)

1832 Reform Act

This proposed reform act was passed by the House of Commons in March, 1831. According to Thomas Macaulay: "Such a scene as the division of last Tuesday I never saw, and never expect to see again. If I should live fifty years the impression of it will be as fresh and sharp in my mind as if it had just taken place. It was like seeing Caesar stabbed in the Senate House, or seeing Oliver taking the mace from the table, a sight to be seen only once and never to be forgotten. The crowd overflowed the House in every part. When the doors were locked we had six hundred and eight members present, more than fifty five than were ever in a division before". (23)

The following month the Tories blocked the measure in the House of Lords. Grey asked William IV to dissolve Parliament so that the Whigs could show that they had support for their reforms in the country. Grey explained this would help his government to carry their proposals for parliamentary reform. William agreed to Grey's request and after making his speech in the House of Lords, walked back through cheering crowds to Buckingham Palace. (24)

Polling was held from 28th April to 1st June 1831. William Lovett, the leader of the National Union of the Working Classes, gave his support to the reformers standing in the election. The Whigs won a landslide victory obtaining a majority of 136 over the Tories. After Lord Grey's election victory, he tried again to introduce parliamentary reform. Enormous demonstrations took place all over England and in Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended these meetings. They were overwhelmingly composed of artisans and working men. (25)

On 22nd September 1831, the House of Commons passed the Reform Bill. However, the Tories still dominated the House of Lords, and after a long debate the bill was defeated on 8th October by forty-one votes. When people heard the news, Reform Riots took place in several British towns; the most serious of these being in Bristol in October 1831, when all four of the city's prisons were burned to the ground. Several people were killed by troops and four of reform leaders were executed. In London, the houses owned by the Duke of Wellington and bishops who had voted against the bill in the Lords were attacked. On 5th November, Guy Fawkes was replaced on the bonfires by effigies of Wellington. (26)

Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, complained: "This detestable Reform Bill has raised the hopes of the utmost. At Plymouth and the neighbouring towns, the spirit is tremendously bad. The shopkeepers are almost all Dissenters, and such is the rage on the question of Reform at Plymouth, that I have received from several quarters the most earnest requests that I will not come to concentrate a church, as I had engaged to do. They assure me that my own person, and the security of the public peace, would be in the greatest danger." (27)

Lord Grey argued in the House of Commons that without reform he feared a violent revolution would take place: "There is no one more decided against annual parliaments, universal suffrage, and the ballot, than I am. My object is not to favour but to put an end to such hopes and projects." (28) The Poor Man's Guardian agreed and it commented that the ruling class felt that "a violent revolution is their greatest dread". (29)

Grey attempted negotiation with a group of moderate Tory peers, known as "the waverers", but failed to win them over. On 7th May a wrecking amendment was carried by thirty-five votes, and on the following day the cabinet resolved to resign unless the king would agree to the creation of peers. On 7th May 1832, Earl Grey and Henry Brougham met the king and asked him to create a large number of Whig peers in order to get the Reform Bill passed in the House of Lords. William was now having doubts about the wisdom of parliamentary reform and refused. (30)

Lord Grey's government resigned and William IV now asked the leader of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington, to form a new government. Wellington tried to do this but some Tories, including Sir Robert Peel, were unwilling to join a cabinet that was in opposition to the views of the vast majority of the people in Britain. Peel argued that if the king and Wellington went ahead with their plan there was a strong danger of a civil war in Britain. He argued that Tory ministers "have sent through the land the firebrand of agitation and no one can now recall it." (31)

When the Duke of Wellington failed to recruit other significant figures into his cabinet, William was forced to ask Grey to return to office. In his attempts to frustrate the will of the electorate, William IV lost the popularity he had enjoyed during the first part of his reign. Once again Lord Grey asked the king to create a large number of new Whig peers. William agreed that he would do this and when the Lords heard the news, they agreed to pass the Reform Act. According to the Whig MP, Thomas Creevey, by taking this action, Grey "has saved the country from confusion, and perhaps the monarch and monarchy from destruction". (32)

Creevey went on to state that it was a great victory against the Tories: "Thank God! I was in at the death of this Conservative plot, and the triumph of the Bill! This is the third great event of my life at which I have been present, and in each of which I have been to a certain extent mixed up - the battle of Waterloo, the battle of Queen Caroline, and the battle of Earl Grey and the English nation for the Reform Bill." (33)

A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has argued that the most import change was that it placed "political power in the hands of the industrial capitalists and their middle class followers." (34) Karl Marx believed that this reform was an example of when one class rules on behalf of another. He pointed out that "the Whig aristocracy was still the governing political class, while the industrial middle class was increasingly the dominant economic one; and the former, generally speaking, represented the interests of the latter." (35)

Most people were disappointed with the 1832 Reform Act. Voting in the boroughs was restricted to men who occupied homes with an annual value of £10. There were also property qualifications for people living in rural areas. As a result, only one in seven adult males had the vote. Nor were the constituencies of equal size. Whereas 35 constituencies had less than 300 electors, Liverpool had a constituency of over 11,000. "The overall effect of the Reform Act was to increase the number of voters by about 50 per cent as it added some 217,000 to an electorate of 435,000 in England and Wales. But 650,000 electors in a population of 14 million were a small minority." Most of the men who took part in the demonstrations, still did not have the vote. (36)

Chartism

Many working people were disappointed when they realised the limitations of the 1832 Reform Act. This disappointment turned to anger when the reformed House of Commons passed the 1834 Poor Law. A measure that reduced the taxation of the middle class and increased the plight of the working class poor. In June 1836 William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands. (37)

"(1) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime. (2) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (3) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (4) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (5) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (6) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period." (38)

When supporters of parliamentary reform held a convention the following year, Lovett was chosen as the leader of the group that were now known as the Chartists. The four main leaders of the Chartist movement had been involved in political campaigns for many years and had all experienced periods of imprisonment. However, they were all strongly opposed to using any methods that would result in violence. Reverend Benjamin Parsons argued: "Do it by moral means alone. Not a pike, a blunderbuss, a brick-bat, or a match, must be found in your hands. In physical force your opponents are mightier than you but in moral force you are ten thousand times stronger than they." (39)

Members of the House of Commons, who supported the Chartists such as Thomas Attwood, Thomas Wakely, Thomas Duncombe and Joseph Hume, constantly emphasized the need to use moral rather than physical force. Lovett, the acknowledged leader of the movement, wrote of how Chartists should "inform the mind" rather than "captivate the senses". Lovett argued that Chartism intended to succeeded through discussion and publication and "without commotion or violence". Moral Force Chartists believed that peaceful methods of persuasion such as the holding of public meetings, the publication of newspapers and pamphlets and the presentation of petitions to the House of Commons would finally convince those in power to change the parliamentary system. (40)

Feargus O'Connor was active in the Chartist movement. However, he was critical of leaders such as William Lovett and Henry Hetherington who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor argued that the concessions the Chartists demanded would not be conceded without a fight, so there had to be a fight. (41)

Supporters of Physical Force such as James Rayner Stephens and George Julian Harney were imprisoned during 1839. Feargus O'Connor was also arrested and in March 1840 he was tried at York for publishing seditious libels in the Northern Star. O'Connor defended himself in a marathon speech of over five hours. He told the jury, "I shall establish my innocence, if not to your satisfaction, to the satisfaction, I trust, of the rest of the world." He was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment. (42)

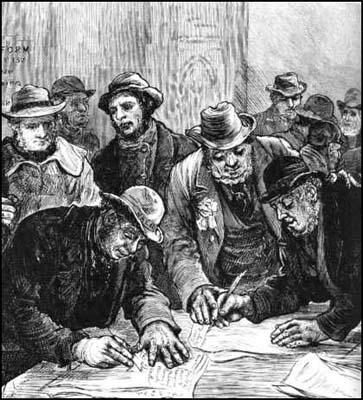

On 10th April 1848, the Chartist movement organised a large meeting at Kennington Common and then presented a petition to the House of Commons that he claimed contained 5,706,000 signatures. This was ignored and William Cuffay, the son of a former slave, and one of the leaders of the London Chartists, called for a General Strike. Cuffay, like George Julian Harney, believed this would eventually result in an armed rising. A government spy called Powell joined Cuffay's group in London. Based on the evidence acquired by Powell, Cuffay was arrested and convicted and sentenced to be transported to Tasmania for 21 years. (43)

Parliamentary Reform

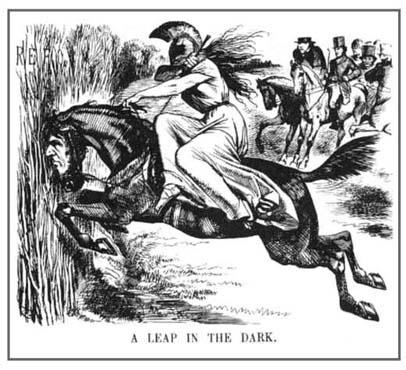

It was because the Chartist movement refused to resort to the threat of violence that they failed to gain any of its six demands. However, it can be argued by conservative commentators like Daniel Finkelstein that giving the vote to some working-class men was not a result of violence in the street or any threat of revolution. In fact, the leaders of the two main political parties, Benjamin Disraeli (Conservative) and William Gladstone (Liberal), both attempted to convince the public they were supporters of parliamentary reform. In 1867 Disraeli, who was very keen to change the image of the Conservative Party, as an anti-reform party, proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later Lord Salisbury) resigned in protest against this proposed extension of democracy. However, as Disraeli explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy." (44)

In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (45)

After the passing of the 1867 Reform Act working class males now formed the majority in most borough constituencies. However, employers were still able to use their influence in some constituencies because of the open system of voting. In parliamentary elections people still had to mount a platform and announce their choice of candidate to the officer who then recorded it in the poll book. Employers and local landlords therefore knew how people voted and could punish them if they did not support their preferred candidate. In 1872 Gladstone removed this intimidation when his government brought in the 1872 Ballot Act which introduced a secret system of voting. Paul Foot points out: "At once, the hooliganism, drunkenness and blatant bribery which had marred all previous elections vanished. employers' and landlords' influence was still brought to bear on elections, but politely, lawfully, beneath the surface." (46)

The 1867 Reform Act had granted the vote to working class males in the towns but not in the counties. William Gladstone and most members of the Liberal Party argued that people living in towns and in rural areas should have equal rights. Lord Salisbury, the new leader of the Conservative Party, opposed any increase in the number of people who could vote in parliamentary elections. Salisbury's critics claimed that he feared that this reform would reduce the power of the Tories in rural constituencies.

In 1884 William Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. The bill faced serious opposition in the House of Commons. The Tory MP, William Ansell Day, argued: "The men who demand it are not the working classes... It is the men who hope to use the masses who urge that the suffrage should be conferred upon a numerous and ignorant class." (47)

The bill was passed by the Commons but was rejected by the Conservative dominated House of Lords. Gladstone refused to accept defeat and reintroduced the measure. This time the Conservative members of the Lords agreed to pass Gladstone's proposals in return for the promise that it would be followed by a Redistribution Bill. Gladstone accepted their terms and the 1884 Reform Act was allowed to become law. This measure gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs - adult male householders and £10 lodgers - and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. (48)

However, this legislation meant that all women and 40% of adult men were still without the vote. According to Lisa Tickner: "The Act allowed seven franchise qualifications, of which the most important was that of being a male householder with twelve months' continuous residence at one address... About seven million men were enfranchised under this heading, and a further million by virtue of one of the other six types of qualification. This eight million - weighted towards the middle classes but with a substantial proportion of working-class voters - represented about 60 per cent of adult males. But of the remainder only a third were excluded from the register of legal provision; the others were left off because of the complexity of the registration system or because they were temporarily unable to fulfil the residency qualifications... Of greater concern to Liberal and Labour reformers... was the issue of plural voting (half a million men had two or more votes) and the question of constituency boundaries." (49)

Votes for Women

In 1887 seventeen individual groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). This organisation, like the Chartists before them, were committed to non-violent protest. However, after nearly 20 years of peaceful campaigns they failed to achieve the vote for women. In 1903, they had achieved nothing and frustrated ed by this lack of progress, Emmeline Pankhurst decided to establish the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic pointed out, it was "not votes for women", but "votes for ladies.” As an early member of the WSPU, Dora Montefiore, pointed out: "The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon... the NUWSS." (50)

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. Therefore the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. This included the use of violence. It seemed certain that the Liberal Party would form the next government. Therefore, the WSPU decided to target leading figures in the party. (51)

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were both arrested. (52)

Christabel Pankhurst was charged with assaulting the police and Annie Kenney with obstruction. They were both found guilty. Pankhurst was fined ten shillings or a jail sentence of one week. Kenney was fined five shillings, with an alternative of three days in prison. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. (53)

Despite the increase in publicity for their cause, the so-called progressive Liberal government, refused to give the vote to women. In 1912 Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. (54)

In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses". (55)

During this period Kitty Marion was the leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign and was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House at St Leonards (April 1913), the Grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse (June 1913) and various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred followed by release under the Cat and Mouse Act. It has been calculated that Marion endured 200 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike. (56)

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (57)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the First World War effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (58)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (59)

Even after the passing of the 1884 Reform Act, only 60% of male householders over the age of 21 had the vote. The British prime minister, David Lloyd George, became concerned that large numbers of those fighting in the First World War also did not have the vote. His attitude towards granting men the vote was influenced by the Russian Revolution in 1917. Would the men returning from the war employ violence to persuade the government to change its policy? And if men serving their country were to be enfranchised, why not women in the services also? If women were not given the vote would they return to the violent tactics used before the war? (60)

"Universal adult suffrage - always, for Lloyd George, an aspiration if not an imperative - had become irresistible." (61) It was therefore decided to introduce the Representation of the People Act. This legislation would allow all men over 21 to vote in future elections. The government also decided that certain categories of women over 30 who met property qualifications. The enfranchisement of this latter group was accepted as recognition of the contribution made by women defence workers. However, women were still not politically equal to men, who could now vote from the age of 21. (62)

The bill for the act was passed by a majority of 385 to 55 in the House of Commons and 134 to 71 votes in the House of Lords. As a result of the Act, the male electorate was extended by 5.2 million to 12.9 million. The female electorate was 8.5 million. After resisting adult male suffrage for over 200 years, there was little opposition from the Conservative Party to this legislation. As Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the party, pointed out in a letter to the former leader, Arthur Balfour, "our party, on the old lines, will never have any future in this country". (63)

The Times argued that protests such as the one that resulted in the Peterloo Massacre were unnecessary, given the fact that parliamentary reform acts eventually brought universal suffrage “without recourse to the revolution that governments had feared since 1789”. (64) However, this is a clear misreading of what had taken place. The fear of revolution never left the ruling classes and was the main reason why adult male suffrage was granted in 1918. In fact, Lloyd George feared that this measure was not enough to avoid revolution. In 1919 over 35 million working days were lost to strikes, and on average every day there were 100,000 workers on strike. There were stoppages in the coal mines, in the printing industry, among transport workers, and the cotton industry. As well as mutinies in the military and two separate police strikes in London and Liverpool. (65)

In 1920 David Lloyd George became convinced that Britain was on the verge of revolution that he was determined to suppress it. After inquiring about the number of troops available to him he asked Sir Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff: "How many airman are available for the revolution? Trenchard replied that there were 20,000 mechanics and 2,000 pilots, but only a hundred machines which could be kept going in the air... The pilots had no weapons for ground fighting. The PM presumed they could use machine guns and drop bombs." The revolution did not take place but it might well have done if Parliament had not passed the Representation of the People Act two years earlier. (66)

John Simkin (21st August, 2019)