First World War: 1914-1916

It was clear that Germany would be a difficult force to defeat. Between 1870 and 1910 the population of the country had increased from 24 million to 65 million. Over 40 per cent of this fast-growing workforce was employed in industry. However, the 35 per cent still working in agriculture ensured that Germany could produce enough food for its people. Germany was recognised as having the most efficient army in the world. Its structure included universal mass conscription for short-term military service followed by a longer period in reserve. In 1914 the regular German Army comprised 25 corps (700,000 men).

The French Army had 47 divisions (777,000 French and 46,000 colonial troops) in 21 regional corps, with attached cavalry and field-artillery units. Most these troops were deployed inside France with the bulk along the eastern frontier as part of Plan 17. With the fear of war with Germany a further 2.9 million men were mobilized during the summer of 1914.

On the outbreak of the First World War it has been claimed that Russia had the largest army in the world. It is believed that there were 5,971,000 men in the Russian Army in August 1914. This was made up of 115 infantry and 38 cavalry divisions. The Russian estimated manpower resource included more than 25 million men of combat age. However, Russia's poor roads and railways made the effective deployment of these soldiers difficult.

Britain had a population of about 42 million in 1914. The British Army had 247,432 regular troops. About 120,000 of these were in the British Expeditionary Army and the rest were stationed abroad.

Britain relied heavily on its navy that included 19 modern dreadnoughts (another 13 under construction), 29 battleships (pre-dreadnought design), 10 battlecruisers, 20 town cruisers, 15 scout cruisers, 200 destroyers and 150 cruisers.

The German Navy was the second largest navy in the world in 1914. It had 13 dreadnoughts (another 7 under construction), 20 battleships, 5 battlecruisers, 7 modern light cruisers and 18 older cruisers. Germany also had 30 petrol-powered submarines and 10 diesel-powered U-boats, with 17 more under construction.

Outbreak of War

On the outbreak of the First World War the editor of The Star newspaper claimed that: "Next to the Kaiser, Lord Northcliffe has done more than any living man to bring about the war." Once the war had started Lord Northcliffe used his newspaper empire to promote anti-German hysteria. It was The Daily Mail that first used the term "Huns" to describe the Germans and "thus at a stroke was created the image of a terrifying, ape-like savage that threatened to rape and plunder all of Europe, and beyond." (1)

Lord Northcliffe dominated the newspaper industry. By 1914 The Daily Mail had a circulation of around 1,400,000. He also owned The Times, The Daily Mirror and The Observer. Although the the Liberal Party had the support of two popular national newspapers, the Daily News and the Daily Chronicle, they found it difficult to compete with the influence of Northcliffe's newspaper empire. Duncan Tanner has pointed out: "They were enthusiastically progressive. They sensationally exposed poverty, making 'political' comparisons between the 'immoral' and 'extreme' wealth of Tory plutocrats and the landlords on the one hand, and the acute and total distress of the poor on the other. Yet between them they had less than three-quarters of a million readers (less than the Tory Daily Mail alone)." (2)

As Philip Knightley, the author of The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth Maker (1982) has pointed out: "The war was made to appear one of defence against a menacing aggressor. The Kaiser was painted as a beast in human form... The Germans were portrayed as only slightly better than the hordes of Genghis Khan, rapers of nuns, mutilators of children, and destroyers of civilisation." (3) In one report the newspaper referred to Kaiser Wilhelm II as a "lunatic," a "barbarian," a "madman," a "monster," a "modern judas," and a "criminal monarch". (4)

The main concern of Lord Northcliffe was a German invasion and was therefore opposed to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) being sent to France. On 5th August, 1914, he warned Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, against any plan to dispatch the BEF. He told the editor of The Daily Mail: "I will not support the sending out of this country of a single British soldier. What about invasion? What about our own country? Put that in the leader. Do you hear? Not a single soldier will go with my consent. Say so in the paper tomorrow." (5)

However, Churchill ignored Northcliffe and it was decided that the 120,000 soldiers in the BEF should be sent to Maubeuge in France. "They (the Army Council) agreed that the fourteen Territorial divisions could protect the country from invasion. The BEF was free to go abroad. Where to? There could be no question of helping the Belgians, through this was why Great Britain had gone to war. The BEF had no choice: it must go to Maubeuge on the French left." (6)

Over the last few months Lord Northcliffe's newspapers campaigned for Lord Kitchener to become Secretary of State for War. It claimed that this post might go to Richard Haldane, a man who Northcliffe believed was pro-German, who had been responsible for delaying war preparations. (7) However, Asquith eventually took Northcliffe's advice and gave Kitchener the post. According to George Arthur, Kitchener's biographer, became Secretary of War because of "the persistence of Lord Northcliffe". (8)

Lord Northcliffe believed that the intertwined national economies of 1914 could not stand more than a few months of conflict. Military experts agreed and predicted that the war would involve battles of movement, fought by professional armies which would be home by Christmas. Northcliffe expected the "British Navy would win the war for Britain by defeating the enemy fleet and blockading Germany". (9)

Kitchener disagreed with Northcliffe on this issue: A.J.P. Taylor has pointed out: "He (Lord Kitchener) startled his colleagues at the first cabinet meeting which he attended by announcing that the war would last three years, not three months, and that Great Britain would have to put an army of millions into the field. Regarding the Territorial Army with undeserved contempt, he proposed to raise a New Army of seventy divisions and, when Asquith ruled out compulsion as politically impossible, agreed to do so by voluntary recruiting." (10)

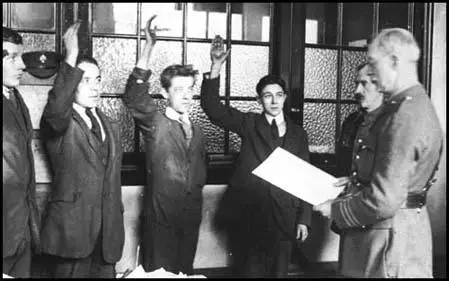

On 7th August, 1914, the House of Commons was told that Britain needed an army of 500,000 men. The same day Lord Kitchener issued his first appeal for 100,000 volunteers. He got an immediate response with 175,000 men volunteering in a single week. With the help of a war poster that featured Kitchener and the words: "Join Your Country's Army", over 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September.

According to his biographer, Keith Neilson: "Kitchener brought to his new office both strengths and weaknesses. He had waged two wars in which he had dealt with all aspects of warfare, including both command and logistics. He was used to being in charge of large enterprises, he was not afraid to take responsibility and make decisions, and he enjoyed public confidence. However, he had no experience of modern European war, almost no knowledge of the British army at home, and a limited understanding of the War Office. Perhaps most importantly, he had no experience of working in a cabinet. Nevertheless in the opening stage of the war he, Asquith, and Churchill formed a dominant triumvirate in the cabinet." (11)

On 8th August 1914, the House of Commons passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) without debate. The legislation gave the government executive powers to suppress published criticism, imprison without trial and to commandeer economic resources for the war effort. During the war publishing information that was calculated to be indirectly or directly of use to the enemy became an offence and accordingly punishable in a court of law. This included any description of war and any news that was likely to cause any conflict between the public and military authorities.

The British government established the War Office Press Bureau under F. E. Smith. The idea was this organisation would censor news and telegraphic reports from the British Army and then issue it to the press. Lord Northcliffe was furious when he heard the news and complained to Smith about the situation. He replied: "We are bound to make mistakes at the start. Give me the advantage throughout of any advice which your experience suggests... Kitchener cannot understand that he is working in a democratic country. He rather thinks he is in Egypt where the press is represented by a dozen mangy newspaper correspondents whom he can throw in the Nile if they object to the way they are treated." (12)

The Daily Mail complained bitterly about the DORA regulations: "Public enthusiasm for our army is not being chilled by the insufficiency of news concerning the British troops at the front. The newspapers do not wish to publish... anything that might be injurious to the military interests of the nation... while we will agree that a careful censorship is necessary for success, it might seem that the reticence in Great Britain has been carried to an unnecessary extreme." (13)

Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, was determined not to have any journalists reporting the war from the Western Front. He instead appointed Colonel Ernest Swinton, to write reports on the war. These were then vetted by Kitchener before being sent to the newspapers. Lord Northcliffe ignored this attempt at press censorship and sent two of his journalists, Hamilton Fyfe and Arthur Moore to France.

On 30th August, 1914, The Times published a report on the problems faced by the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. "The German advance has been one of almost incredible rapidity... The Germans, fulfilling one of the best of all precepts in war, never gave the retreating army one single moment's rest. The pursuit was immediate, relentless, unresting. Aeroplanes, Zeppelins, armoured motors, were loosed like an arrow from the bow... Regiments were grievously injured, and the broken army fought its way desperately with many stands, forced backwards and ever backwards by the sheer unconquerable mass of numbers... Our losses are very great. I have seen the broken bits of mass regiments... The German commanders in the north advance their men as if they had an inexhaustible supply." (14)

In the House of Commons, William Llewelyn Williams asked H. H. Asquith was aware of the report that British forces had suffered a major defeat in France. The prime minister replied: "It is impossible too highly to commend the patriotic reticence of the Press as a whole from the beginning of the war up to the present moment. The publication to which my honourable friend refers appears to be a very regrettable exception - and I hope it will not recur... The Government feel after the experience of the last two weeks that the public is entitled to information - prompt and authentic information - of what is happening at the front, and which they hope will be more adequate." (15)

Winston Churchill wrote to Lord Northcliffe and complained about the article: "I think you ought to realize the damage that has been done by Sunday's publication in the Times. I do not think you can possibly shelter yourself behind the Press Bureau, although their mistake was obvious. I never saw such panic-stricken stuff written by any war correspondent before; and this served up on the authority of the Times can be made, and has been made, a weapon against us in every doubtful state." (16)

Lord Northcliffe replied: "This is not a time for Englishmen to quarrel... Nor will I discuss the facts and tone of the message, beyond saying that it came from one of the most experienced correspondents in the service of the paper. I understand that not a single member of the staff on duty last Saturday night expected to see it passed by the Press Bureau." He then pointed out that it was not only passed but carefully edited and it seemed that the government actually wanted it to published. (17)

Controlling the News

On 8th August 1914, the House of Commons passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) without debate. The legislation gave the government executive powers to suppress published criticism, imprison without trial and to commandeer economic resources for the war effort. During the war publishing information that was calculated to be indirectly or directly of use to the enemy became an offence and accordingly punishable in a court of law. This included any description of war and any news that was likely to cause any conflict between the public and military authorities.

The British government also established the War Office Press Bureau under F. E. Smith. The idea was this organisation would censor news and telegraphic reports from the British Army and then issue it to the press. Lord Northcliffe was furious when he heard the news and complained to Smith about the situation. He replied: "We are bound to make mistakes at the start. Give me the advantage throughout of any advice which your experience suggests... Kitchener cannot understand that he is working in a democratic country. He rather thinks he is in Egypt where the press is represented by a dozen mangy newspaper correspondents whom he can throw in the Nile if they object to the way they are treated." (18)

The Daily Mail complained bitterly about the DORA regulations: "Public enthusiasm for our army is not being chilled by the insufficiency of news concerning the British troops at the front. The newspapers do not wish to publish... anything that might be injurious to the military interests of the nation... while we will agree that a careful censorship is necessary for success, it might seem that the reticence in Great Britain has been carried to an unnecessary extreme." (19)

Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, was determined not to have any journalists reporting the war from the Western Front. He instead appointed Colonel Ernest Swinton, to write reports on the war. These were then vetted by Kitchener before being sent to the newspapers. Lord Northcliffe ignored this attempt at press censorship and sent two of his journalists, Hamilton Fyfe and Arthur Moore to France.

On 30th August, 1914, The Times published a report on the problems faced by the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. "The German advance has been one of almost incredible rapidity... The Germans, fulfilling one of the best of all precepts in war, never gave the retreating army one single moment's rest. The pursuit was immediate, relentless, unresting. Aeroplanes, Zeppelins, armoured motors, were loosed like an arrow from the bow... Regiments were grievously injured, and the broken army fought its way desperately with many stands, forced backwards and ever backwards by the sheer unconquerable mass of numbers... Our losses are very great. I have seen the broken bits of mass regiments... The German commanders in the north advance their men as if they had an inexhaustible supply." (20)

In the House of Commons, William Llewelyn Williams asked H. H. Asquith was aware of the report that British forces had suffered a major defeat in France. The prime minister replied: "It is impossible too highly to commend the patriotic reticence of the Press as a whole from the beginning of the war up to the present moment. The publication to which my honourable friend refers appears to be a very regrettable exception - and I hope it will not recur... The Government feel after the experience of the last two weeks that the public is entitled to information - prompt and authentic information - of what is happening at the front, and which they hope will be more adequate." (21)

Winston Churchill wrote to Lord Northcliffe and complained about the article: "I think you ought to realize the damage that has been done by Sunday's publication in the Times. I do not think you can possibly shelter yourself behind the Press Bureau, although their mistake was obvious. I never saw such panic-stricken stuff written by any war correspondent before; and this served up on the authority of the Times can be made, and has been made, a weapon against us in every doubtful state." (22)

Lord Northcliffe replied: "This is not a time for Englishmen to quarrel... Nor will I discuss the facts and tone of the message, beyond saying that it came from one of the most experienced correspondents in the service of the paper. I understand that not a single member of the staff on duty last Saturday night expected to see it passed by the Press Bureau." He then pointed out that it was not only passed but carefully edited and it seemed that the government actually wanted it to published. (23)

In August 1914 the British government established the War Office Press Bureau under F. E. Smith. The idea was this organisation would censor news and telegraphic reports from the British Army and then issue it to the press. Lord Kitchener decided to appoint Colonel Ernest Swinton to become the British Army's official journalist on the Western Front. Swinton's reports were first censored at G.H.Q. in France and then personally vetted by Kitchener before being released to the press. Letters written by members of the armed forces to their friends and families were also read and censored by the military authorities.

Some journalists were already in France when war was declared in August 1914. Philip Gibbs, a journalist working for The Daily Chronicle, quickly attached himself to the British Expeditionary Force and began sending in reports from the Western Front. When Lord Kitchener discovered what was happening he ordered the arrest of Gibbs. After being warned that if he was caught again he "would be put up against a wall and shot", Gibbs was sent back to England. (24)

The result of Lord Kitchener's policy was that during the early stages of the war British journalists in France were treated as outlaws. They could be arrested at any time and by any officer, either French or British who discovered them. Kitchener gave orders that any correspondent found would be immediately arrested, expelled and have his passport cancelled. "under these conditions it was difficult for the war correspondents to get reports and messages to their newspapers." (25)

Basil Clarke of The Daily Mail later recalled: "I count it among my achievements that I was never once arrested. The difficulties were numerous. Even to live in the war zone without papers and credentials was hard enough, but to move about and see things, and pick up news and then to get one's written dispatches conveyed home - against all regulations - was a labour greater and more complex than anything I have ever undertaken in journalistic work. I longed sometimes to be arrested and sent home and done with it all." (26)

German Atrocities

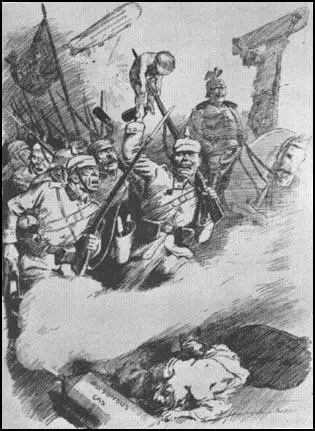

During the First World War most countries publicized stories of enemy soldiers committing atrocities. It was believed that it would help persuade young men to join the armed forces. As one British general pointed out after the war: "to make armies go on killing one another it is necessary to invent lies about the enemy". These atrocity stories were then fed to newspapers who were quite willing to publish them. British newspapers accused German soldiers of a series of crimes including: gouging out the eyes of civilians, cutting off the hands of teenage boys, raping and sexually mutilating women, giving children hand grenades to play with, bayoneting babies and the crucifixion of captured soldiers. Wythe Williams, who worked for the New York Times, investigated some of these stories and reported "that none of the rumours of wanton killings and torture could be verified."

Lord Northcliffe's newspapers were willing to publish stories about German "atrocities" in Belgium and France. On 17th August 1914 The Daily Mail carried accounts of how German soldiers had murdered five civilians. (27) A few days later Hamilton Fyfe chronicled the "sins against civilization" and the "barbarity" of the Germans. He also wrote a story about how Germans had cut off the hands of Red Cross workers and had used women and children as shields in battle". (28)

This was followed by a fuller account of the atrocities: "The measured, detailed, and we fear unanswerable indictment of Germany's conduct of the war issued yesterday by the Belgian minister is a catalogue of horrors that will indelibly brand the German name in the eyes of all mankind.. This is no ordinary arraignment... concerned not with hearsay evidence, but with incidents that in each case have been carefully investigated... After making every deduction for national bias and the possibility of error, there remains a record of sheer brutality that will neither be forgiven or forgotten." (29)

Robert Graves, who served on the Western Front, raised doubts about the truth of these stories, in his book on the war, Goodbye to All That: "French and Belgian civilians had often tried to win our sympathy by exhibiting mutilations of children - stumps of hands and feet, for instance - representing them as deliberate, fiendish atrocities when, as likely as not, they were merely the result of shell-fire. We did not believe rape to be any more common on the German side of the line than on the Allied side. And since a bully-beef diet, fear of death, and absence of wives made ample provision of women necessary in the occupied areas, no doubt the German army authorities provided brothels in the principal French towns behind the line, as the French did on the Allied side. We did not believe stories of women's forcible enlistment in these establishments. What's wrong with the voluntary system? we asked cynically." (30)

Trench Warfare

The Battle of the Marne began on the 5th September, 1914. General Joseph Joffre told his troops: "At the moment when the battle upon which hangs the fate of France is about to begin, all must remember that the time for looking back is past; every effort must be concentrated on attacking and throwing the enemy back... Troops must at any cost keep the ground that has been won, and must die where they stand rather than give way... Under present conditions no weakness can be tolerated." (31)

After the Battle of the Marne in September, 1914, the Germans were forced to retreat to the River Aisne. The German commander, General Erich von Falkenhayn, decided that his troops must at all costs hold onto those parts of France and Belgium that Germany still occupied. Falkenhayn ordered his men to dig trenches that would provide them with protection from the advancing French and British troops. The Allies soon realised that they could not break through this line and they also began to dig trenches. "The war of rapid movement was over... The German hopes of reaching the sea were as vain as the British hopes of pushing deep into Belgium." (32)

After a few months these trenches had spread from the North Sea to the Swiss Frontier. As the Germans were the first to decide where to stand fast and dig, they had been able to choose the best places to build their trenches. The possession of the higher ground not only gave the Germans a tactical advantage, but it forced the British and French to live in the worst conditions. Most of this area was rarely a few feet above sea level. As soon as soldiers began to dig down they would invariably find water two or three feet below the surface.

Water-logged trenches were a constant problem for soldiers on the Western Front. One soldier wrote to his father, explaining the situation: "Hell is the only word descriptive of the weather out here and the state of the ground. It rains every day! The trenches are mud and water up to one's neck, rendering some impassable - but where it is up to the waist we have to make our way along cheerfully. I can tell you - it is no fun getting up to the waist and right through, as I did last night. Lots of men have been sent off with slight frost-bite - the foot swells up and gets too big for the boot." (33)

Frontline trenches were usually about seven feet deep and six feet wide. The front of the trench was known as the parapet. The top two or three feet of the parapet and the parados (the rear side of the trench) would consist of a thick line of sandbags to absorb any bullets or shell fragments. In a trench of this depth it was impossible to see over the top, so a two or three-foot ledge known as a fire-step, was added. Trenches were not dug in straight lines. Otherwise, if the enemy had a successive offensive, and got into your trenches, they could shoot straight along the line. Each trench was dug with alternate fire-bays and traverses.

Duck-boards were also placed at the bottom of the trenches to protect soldiers from water. Soldiers also made dugouts and funk holes in the side of the trenches to give them some protection from the weather and enemy fire. One of the worst problems for the soldiers was trench foot. Lieutenant Ulrich Burke later commented: "Trench foot was owing to the mud soaking through your boots and everything. In many cases your toes nearly rotted off. We lost more that way than we did from any wounds or anything." (34)

The front-line trenches were also protected by barbed-wire entanglements and machine-gun posts. Short trenches called saps were dug from the front-trench into No-Man's Land. The sap-head, usually about 30 yards forward of the front-line, were then used as listening posts. Small groups of soldiers were given the task of finding out about the enemy. This included discovering information about enemy patrols, wiring parties, or sniper positions. After a heavy bombardment soldiers would be ordered to seize any new craters in No Man's Land which could then be used as listening posts.

Order of the White Feather

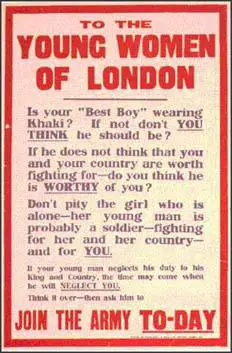

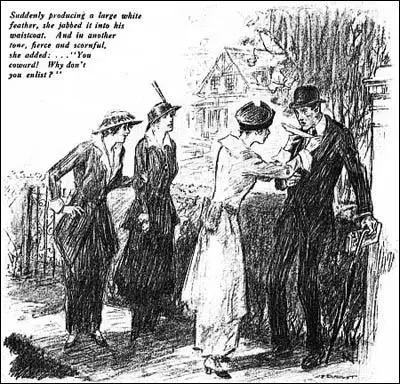

In August 1914, Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald founded the Order of the White Feather. (35) He deputized thirty women in Folkestone to give out white feathers to any men not in uniform. The concept was based on the old cock-fighting lore that a cockerel with a white feather in its tail is a coward. (36)

With the support of leading writers such as Mary Ward and Emma Orczy, the organisation encouraged women to give out white feathers to young men who had not joined the armed forces. Lord Kitchener gave his support to the campaign: "The women could play a great part in the emergency by using their influence with their husbands and sons to take their proper share in the country's defence, and every girl who had a sweetheart should tell men that she would not walk out with him again until he had done his part in licking the Germans." (37)

The Daily Mail enthusiastically reported the activities of the Order of the White Feather, hoping the gesture "would shame every young slacker" into enlisting. "The generally female white feather distributors achieved much notoriety by frequently misjudging their targets, stories of men on leave, wounded, or in reserved occupations being handed down these odious symbols abound." (38)

One young woman remembers her father, Robert Smith, being given a feather on his way home from work: "That night he came home and cried his heart out. My father was no coward, but had been reluctant to leave his family. He was thirty-four and my mother, who had two young children, had been suffering from a serious illness. Soon after this incident my father joined the army." Frederick Broome was only fifteen years of age, when he "accosted by four girls who gave me three white feathers." (39)

The government became concerned when women began presenting state employees with white feathers. It was suggested to Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, that these women should be arrested for "conduct likely to disrupt the police". McKenna refused but he did arrange for state employees to be issued with badges testifying that they were serving "King and Country".

Although he was a serving soldier, the writer, Compton Mackenzie, complained about the activities of the Order of the White Feather. He argued that these "idiotic young women were using white feathers to get rid of boyfriends of whom they were tired". The pacifist, Fenner Brockway, claimed that he received so many white feathers he had enough to make a fan. (40)

Another man was given a white feather on the same day he had been presented with the Victoria Cross at Buckingham Palace. (41) However, Lucy Noakes has defended these women by explaining that their actions were "more expressive of the desire amongst many women to be doing something, anything to help the war effort, rather than as evidence of a widespread jingoism amongst the female population." (42)

Private Harold Carter was on leave from the Western Front. "On the Saturday I went to a music hall in civilian clothes and as I lined up outside a lady came along and put a white feather into my hand. I looked at it and felt disgusted, but there wasn't much I could do about it. I felt small enough over the white feather incident outside, but as I went into the gallery a chap came out in naval uniform and said that no girl should be sitting with a chap unless he was in uniform." (43)

William Brooks was also given a white feather at the age of sixteen. "Once war broke out the situation at home became awful, because people did not like to see men or lads of army age walking about in civilian clothing, or not in uniform of some sort, especially in a military town like Woolwich. Women were the worst. They would come up to you in the street and give you a white feather, or stick it in the lapel of your coat. A white feather is the sign of cowardice, so they meant you were a coward and that you should be in the army doing your bit for king and country.... In 1915 at the age of seventeen I volunteered under the Lord Derby scheme. Now that was a thing where once you applied to join you were not called up at once, but were given a blue armband with a red crown to wear. This told people that you were waiting to be called up, and that kept you safe, or fairly safe, because if you were seen to be wearing it for too long the abuse in the street would soon start again."

James Cutmore had attempted to volunteer for the British Army in 1914 but was rejected because he was short-sighted. "But in 1916, as he walked home to south London from his office, a woman gave him a white feather.... He enlisted the next day. By that time, they cared nothing for short sight. They just wanted a body to stop a shell, which Rifleman James Cutmore duly did in February 1918, dying of his wounds on March 28. My mother was nine, and never got over it. In her last years, in the 1980s, her once fine brain so crippled by dementia that she could not remember the names of her children, she could still remember his dreadful, lingering, useless death. She could still talk of his last leave, when he was so shell-shocked he could hardly speak and my grandmother ironed his uniform every day in the vain hope of killing the lice." (44)

Recruitment Orators

The most famous recruitment orators was Horatio Bottomley. On the outbreak of the First World War, Bottomley told his personal assistant, Henry J. Houston: "Houston, this war is my opportunity. Whatever I have been in the past, and whatever my faults, I am going to draw a line at August 4th, 1914, and start afresh. I shall play the game, cut all my old associates, and wipe out everything pre-1914". Houston later recalled: "At the time I thought he meant it, but but now I know that the flesh, habituated to luxury and self-indulgence, was too weak to give effect to the resolution. For a while he did try to shake off his old associates, but the claws of the past had him grappled in steel, and the effort did not last more than a few weeks." (45)

In September 1914, the first recruiting meetings were held in London. The first meetings were addressed by government ministers. Bottomley told Houston: "These professional politicians don't understand the business. I am going to constitute myself the Unofficial Recruiting Agent to the British Empire. We must have a big meeting." His first meeting at the Albert Hall was so popular that according to Houston, Bottomley "was unable for two hours to get into his own meeting." (46)

Bottomley wrote to Herbert Henry Asquith about the possibility of becoming Director of Recruiting. Asquith replied: "Thank you for your offer but I shall not avail myself of it at the moment. You are doing better work where you are." Asquith, aware of his popularity, encouraged him to do this work in an unofficial capacity. It has been claimed at the time that he was paid between £50 and £100 to address meetings where he encouraged young men to join the armed forces. Henry J. Houston claimed that he spoke at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square, and delivered a ten minutes' speech each night for a week at a fee of £600. Later, Bottomley "secured a week's engagement, two houses nightly, at the Glasgow Pavilion, where he received a fee of £1,000." (47)

It has been calculated that Bottomley addressed twenty recruiting meetings and 340 "patriotic war lectures". Although he had been highly critical of the government, at the meetings he always stated: "When the country is at war, it is the duty of every patriot to say: My country right or wrong; My government good or bad." He also falsely claimed that he was "not going to take money for sending men out to their death, or profit from his country in its hour of need." Bottomley claimed that he used the meetings to publicise John Bull Magazine and according to Houston, he drew over £22,000 from the journal for his efforts.

Almost alone amongst left-wing political figures, Victor Grayson gave recruiting speeches and wrote articles urging young men to join the armed forces. Some socialists accused him of being paid by the government to make these speeches. He attempted to explain why he changed his views on war: "This war has made havoc of many ready-made theories and doctrines, and some of my most cherished antipathies have succumbed to its effects. I am facing the fact that some 178 Peers of the Realm are now in khaki fighting an enemy country." (48)

In an interview Grayson gave to a newspaper he argued that the working-class would be rewarded if the Allied forces won the war: "The war has cast everything into the crucible. So far as Socialism can be defined intelligently, I still believe that the products of the workers belong to the workers... The war has wrought a marvellous change in the division of classes and masses. The working man has changed his attitude towards the worker, hence new political, industrial and ethical conditions will be the result of our inevitable triumph." (49)

Union of Democratic Control

Opponents of the war in the Labour Party joined forces with rebels in the Liberal Party to form the Union of Democratic Control. Members of the UDC agreed that one of the main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the Union of Democratic Control should have three main objectives: (i) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (ii) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organization to help prevent future conflicts; (iii) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars. (50)

Ramsay MacDonald came under attack from newspapers because of his opposition to the First World War. On 1st October 1914, The Times published a leading article entitled Helping the Enemy, in which it wrote that "no paid agent of Germany had served her better" that MacDonald had done. The newspaper also included an article by Ignatius Valentine Chirol, who argued: "We may be rightly proud of the tolerance we display towards even the most extreme licence of speech in ordinary times... Mr. MacDonald' s case is a very different one. In time of actual war... Mr. MacDonald has sought to besmirch the reputation of his country by openly charging with disgraceful duplicity the Ministers who are its chosen representatives, and he has helped the enemy State ... Such action oversteps the bounds of even the most excessive toleration, and cannot be properly or safely disregarded by the British Government or the British people." (51)

In May 1915, Arthur Henderson, became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. Bruce Glasier commented in his diary: "This is the first instance of a member of the Labour Party joining the government. Henderson is a clever, adroit, rather limited-minded man - domineering and a bit quarrelsome - vain and ambitious. He will prove a fairly capable official front-bench man, but will hardly command the support of organised Labour." (52)

Horatio Bottomley, argued in the John Bull Magazine that Ramsay MacDonald and James Keir Hardie, were the leaders of a "pro-German Campaign". On 19th June 1915 the magazine claimed that MacDonald was a traitor and that: "We demand his trial by Court Martial, his condemnation as an aider and abetter of the King's enemies, and that he be taken to the Tower and shot at dawn." (53)

On 4th September, 1915, the magazine published an article which made an attack on MacDonald's background. "We have remained silent with regard to certain facts which have been in our possession for a long time. First of all, we knew that this man was living under an adopted name - and that he was registered as James MacDonald Ramsay - and that, therefore, he had obtained admission to the House of Commons in false colours, and was probably liable to heavy penalties to have his election declared void. But to have disclosed this state of things would have imposed upon us a very painful and unsavoury duty. We should have been compelled to produce the man's birth certificate. And that would have revealed what today we are justified in revealing - for the reason we will state in a moment... it would have revealed him as the illegitimate son of a Scotch servant girl!" (54)

Raymond Asquith

The prime minister, H. H. Asquith, had four sons on the outbreak of the war. Cyril (24), Arthur (31) and Herbert (33) immediately joined the armed forces. Herbert pointed out "England expects every man to do his duty" and if they did not offer their services "Father will be asked why he doesn't begin his recruiting at home". Arthur agreed and was the first to join: "I have two older brothers, both married, and one younger brother with an ailing colon... It is obviously fitting that one of my father's four sons ought to be prepared to fight". (55)

Raymond Asquith, was nearly 36 and was married with two young children, Helen and Perdita. A third child, Julian would be born soon afterwards. He was less enthusiastic about the war than his younger brothers. Raymond was on the left of the Liberal Party and had doubts about the wisdom of declaring war on Germany. He had no confidence in Lord Kitchener, who he described as the "King of Chaos" and expected the war to last at least three years and predicted that "sooner or later they (his brothers) would all be under the turf". (56)

Arthur Asquith was the first to see action in the 2nd Royal Naval Division, a collection of naval reservists that became known as the Anson Battalion that had been formed by Winston Churchill. A fellow officer was his friend Rupert Brooke. On 8th October, 1914, the battalion attempted to take the port of Antwerp, from the German Army. This ended in failure and they were forced to escape back to England.

Asquith later wrote to Venetia Stanley about what happened: "I can't tell you what I feel of the wicked folly of it all. The Marines of course are splendid troops and can go anywhere and do anything: but nothing excuses Winston Churchill (who knew all the facts)... I was assured that all the recruits were being left behind, and that the main body at any rate consisted of seasoned Naval Reserve men. As a matter of fact only about a quarter were Reservists, and the rest were a callow crowd of the rawest tiros, most of whom had never fired off a rifle, while none of them had ever handled an entrenching tool." (57)

Herbert Asquith was also sent to Belgium and saw action at Nieuwpoort. He later recalled: "The ground was scattered with large numbers of the dead, French and German, lying on that powdered and shell-pitted soil, on their faces or their backs, tangled on the barbs of the rusted wire, or tossed over the brink of a shell-hole, and here and there a rigid arm stretched upwards aimlessly to the sky." (58)

Despite his doubts about the war, Raymond Asquith joined the Queen's Westminster Rifles in January 1915. "As the months went by with no sign of the regiment being sent abroad, Raymond... became increasingly frustrated with such futile tasks as stopping suspicious vehicles approaching London from the North-West." His wife, afraid that he would seek to serve abroad, tried to convince him to stand as a Liberal Party candidate in a by-election, but he rejected the idea as he saw it as an act of cowardice. (59)

His friend, Hugh Godley, later wrote: "Raymond was so absolutely unmilitary and when the war came, he went into it not with any burning enthusiasm, but just as a sort of matter of course, and he went on with his soldiering just as he went on with his own profession before, in the conscientious methodical way which was so characteristic of him... fully realizing what the end might be, but never to all appearances in the least conscious of it." (60)

Aware that he would not see active service in this regiment he transferred as a lieutenant into the 3rd battalion of the Grenadier Guards and went out to the Western Front in October, 1915. Margot Asquith wrote: "Raymond left this morning... I was almost surprised at how sad I felt at parting with him - there was something so pathetic and incongruous in seeing so perfect and highly finished a being going off into that raw brutal primitive hurly-burly." (61)

H. H. Asquith was furious with his son and refused to write to him while he was on the Western Front. However, he was posted to one of the comparatively quiet sections of the front line, where shelling was sporadic. He wrote to his friend, Diana Manners, that he was more concerned by the discomfort than the danger, complaining about "being up to his neck in dense, sticky blue clay; at the same time he was puzzled that while the sound of rifle fire seemed no more far off than the next gun in a partridge drive". (62)

In an early letter to his wife from the front he complained about the lack of dry trenches and the failures of the authorities in making no adequate preparations for winter, claiming that half of his men did not have trench boots. He also noted the contempt felt for staff officers behind the lines by those in the trenches, and felt that she would think he was right not to become one, "though of course one may find in the end that there are more uncomfortable things than general abuse". (63)

Raymond Asquith was very unimpressed with the training for creeping barrage that took place before the attack on the German front-line trenches. Colin Clifford has commented: "He had been up since five o'clock participating in an exercise designed to simulate an attack on enemy trenches behind a creeping barrage, the recently devised tactic of laying down a steadily moving curtain of shell fire some fifty yards in front of the infantry as they advanced. In the exercise the barrage was simulated by drummers, allowing him to give full rein to his sense of the ridiculous. To him the sight of four battalions walking in lines at a funeral pace across cornfields preceded by a row of drummers was more like some ridiculous religious ritual ceremony performed by a Maori tribe, than a brigade of Guards training for battle." (64)

On the Western Front in December 1914 there was a spontaneous outburst of hostility towards the killing. On 24th December, arrangements were made between the two sides to go into No Mans Land to collect the dead. Negotiations also began to arrange a cease-fire for Christmas Day. On other parts of the front-line, German soldiers initiated a cease-fire through song. On Christmas Day the guns were silent and there were several examples of soldiers leaving their trenches and exchanging gifts. The men even played a game of football. (65)

In January 1916, Asquith was asked to work as defence counsel to Ian Colquhoun who was being court-martialled for "allowing his men to fraternise with the Germans on Christmas Day". Raymond was impressed by Colquhoun "for the vigour and nerve with which he faced his accusers" and in his "insolence, aplomb, courage and elegant virility". Despite his efforts, Colquhoun was convicted but escaped with a reprimand. (66)

Raymond Asquith resisted attempts by his father to use his influence to transfer him onto the General Staff but against his wishes he did serve for four months (January to May 1916) at general headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force, at Saint-Omer, where he "served unenthusiastically in intelligence work". (67)

During this period he became greatly concerned about the influence of Lord Northcliffe and his newspapers, The Times and The Daily Mail. There were constant criticism of Asquith, especially over the reluctance of accepting the need of conscription (compulsory enrollment). "Raymond was an indignant as anyone, telling Katherine Asquith that he had reached the stage when he would rather defeat Northcliffe than defeat the Germans. The press lord seemed to him just as belligerently crass and crassly belligerent as the enemy were, but far less courageous and capable". (68)

Raymond Asquith returned to the Western Front on 16th May 1916. He became increasingly critical of the way the war was being fought. He told his wife that "almost every night there were raids on the German lines accompanied by the usual ridiculous artillery barrage" and he "considered the whole business to be a charade, usually causing far more British than German casualties". (69)

On 7th September, 1916, H. H. Asquith visited the front-line and managed to obtain a meeting with his son. He wrote to Margot Asquith that evening: "He was very well and in good spirits. Our guns were firing all round and just as we were walking to the top of the little hill to visit the wonderful dug-out, a German shell came whizzing over our heads and fell a little way beyond... We went in all haste to the dug-out - 3 storeys underground with ventilating pipes electric light and all sorts of conveniences, made by the Germans. Here we found Generals Horne and Walls (who have done the lion's share of all the fighting): also Bongie's brother who is on Walls's staff. They were rather disturbed about the shell, as the Germans rarely pay them such attention, and told us to stay with them underground for a time. One or two more shells came, but no harm was done. The two generals are splendid fellows and we had a very interesting time with them." (70)

On 15th September, Raymond Asquith led his men on an attack on the German trenches at Lesboeufs. According to one of his men "such coolness under shell fire as he displayed would be difficult to equal". Soon after leaving the trench he was hit in the chest by a bullet. Raymond knew straightaway that his wound was fatal, but in order to reassure his men, he casually lit a cigarette as he was carried on a stretcher to the dressing station. A medical orderly wrote to his father to say he was not given morphia "as he was quite free from pain and just dying." (71)

Raymond Asquith died on the way to the dressing station. According to a soldier quoted by John Jolliffe: "There is not one of us who would not have changed places with him if we had thought that he would have lived, for he was one of the finest men who ever wore the King's uniform, and he did not know what fear was." Only five of the twenty-two officers in Asquith's battalion survived the battle unscathed. (72)

When his father was informed of his death "he put his head on his arms on the table and sobbed passionately". He told Margot Asquith: "The awful waste of a man like Raymond - the best brain of his age in our time - any career he liked lying in front of him. I always felt it would happen." Two days later he wrote to Sylvia Henley: "I can honestly say, that in my own life he was the thing of which I was truly proud, and in him and his future I had invested all my stock of hope." (73)

On 22nd September, 1916, Raymond's sister, Violet Bonham Carter, wrote: "He was shot through the chest and carried back to a shell-hole where there was an improvised dressing station. There they gave him morphia and he died an hour later. God bless him. How he has vindicated himself - before all those who thought him merely a scoffer - by the modest heroism with which he chose the simplest and most dangerous form of service - and having so much to keep for England gave it all to her with his life." (74)

H. H. Asquith and Venetia Stanley

H. H. Asquith was considered a ladies man in his younger years. After he became prime minister he liked the company of young women. Diana Cooper complained that on several occasions she had to defend her face "from his fumbly hands and mouth". (75) The Asquith family were fully aware of his inappropriate behaviour. His daughter-in-law, Cynthia Asquith, wrote about it in her diary but according to her biographer, Nicola Beauman, she was forced to "ink over all references in her diary". Ottoline Morrell was another woman who complained about his behaviour. Apparently she told Lytton Strachey that Asquith "would take a lady's hand, as she sat beside him on the sofa, and make her feel his erected instrument under his trousers". (76)

The most important of these women was the 25 year-old Venetia Stanley, a close friend of his daughter, Violet Asquith. The two women went on holiday to Sicily with Asquith and his young protégé, Liberal Party MP, Edwin Montagu. Over the next two weeks both men fell in love with Venetia. Asquith, was 59 years old at the time and in a letter to her later he described the holiday as "the first stage in our intimacy... we had together one of the most interesting and delightful fortnights in all our lives... the scales dropped from my eyes… and I dimly felt… that I had come to a turning point in my life". (77)

On their return from holiday Asquith invited Venetia to a house party, following this up with invitations to 10 Downing Street. However, he was unaware that Montagu was also besotted with Venetia. He wrote to her regularly and took her out whenever he could. It seems that Asquith was totally unaware of this developing relationship. In August 1912 he asked her to marry him. At first she accepted the proposal and later changed her mind. (78)

If Venetia accepted his proposal he would have lost his inheritance as his father, Samuel Montagu, 1st Baron Swaythling, who had died in 1911, had stipulated in his will that he had to marry a Jewish woman. "Although Venetia, physically repelled by his huge head and course pock-marked face, refused him, she lapped up the waspish political gossip at which he excelled, and they continued to see a great deal of one another, with Montagu a regular house guest at the Stanley family homes at Alderley and Penrhos." (79)

After the outbreak of the First World War Asquith began writing to Venetia daily. This included a "great many political and war secrets, and remained, as far as is known, completely discreet about them all". Venetia became concerned that Asquith was becoming increasing dependence on her friendship, and to have warned him that he could not remain the centre of her life. However, she found it difficult to break with him when she saw how much she had distressed him she would "make him happy again" by saying "anything he wanted". (80)

Asquith's language became more passionate in 1915 and appeared to be more besotted with his young friend. "I love you more than ever - more than life!" (81) Six days later he wrote: "I can honestly say that not an hour passes without thought of you." (82) These letters were written at a time of national crisis and newspapers, especially those owned by Lord Northcliffe, were suggesting he was a poor war leader. On 22nd March, Asquith told Venetia that "I have never wanted you more." (83)

Jonathan Walker, the author of The Blue Beast: Power and Passion in the Great War (2012), has argued that Asquith "needed Venetia as a sounding board and to confirm that he was still intellectually alive". He suggests that Asquith "probably did not have the physical stamina to keep up with a highly-strung beauty, preferring a mistress who could stimulate his intellect and massage his ego." (84)

When she suggested going overseas to work as a nurse with the British troops Asquith protested that he would not be able to cope with her "so far away". In several letters he expressed his fears of losing her. He confessed that "sometimes a horrible imagination seizes me that you may be taken from me - in one way or another". If she did try try to go abroad he feared she would be a victim of a submarine attack and this developed "a suicidal mood" in him. (85)

Margot Asquith became increasingly jealous of Venetia and after an outburst of anger he wrote a letter about his situation. He explained how he had been under tremendous pressure: "These last 3 years I have lived under a perpetual strain, the like of which has I suppose been experienced by very few men living or dead. It is no exaggeration to say that I have on hand more often half-a-dozen problems than a single one - personal, political, Parliamentary etc - most days of the week... I admit that I am often irritated and impatient, and then I become curt and perhaps taciturn. I fear you have suffered from this more than anyone, and I am deeply sorry, but believe me darling it has not been due to want of confidence and love. Those remain and will always be unchanged."

He then went on to argue that Venetia had been very helpful during this period. "You have and always will have (as no one knows so well as I) far too large a nature - the largest I have known - to harbour anything in the nature of petty jealousies. But you would have just reason for complaint, and more, if it were true that I was transferring my confidence from you to anyone else. My fondness for Venetia has never interfered and never could with our relationship. She has a fine character as well as great intelligence, and often does less than justice to herself (as over this Hospital business) by her minimising way of talking." (86)

On 30th March, 1915, Asquith wrote to Venetia four times. Disturbed by his intense love of her she decided to bring an end to the relationship by marrying Edwin Montague. He had recently joined the cabinet as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. John Grigg has pointed out: "Still only in his middle thirties, he had risen in politics as Asquith's protégé but was far from being a mere hanger-on... Rich and privileged, intellectually a late-developer, sensitive and emotional yet capable of a certain ruthlessness, he was now becoming a rather important figure." (87)

Montagu now had status as well as money. Venetia Stanley decided to accept his proposal of marriage. "For Montagu, religion was a purely personal affair; he had no formal religious beliefs, was anti-Zionist, and constantly emphasized his foremost identity as a Briton". However, in order that Montagu could continue to receive an annual income of £10,000 from his father's estate, Venetia was compelled to convert to Judaism. (88)

On 12th May 1915, Asquith was shocked and appalled to receive Venetia's letter announcing her engagement to the man who he recently appointed as his Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Asquith replied that this news "breaks my heart" and that he "couldn't bear to come and see you". (89)

On the day he heard the news Asquith wrote three letters to Venetia's sister, Sylvia Henley, about the proposed marriage. In the second letter he pointed out: "I had never any illusions, and often told Venetia: and she also was always most frank about her someday getting married. But this. We have always treated it as a kind of freakish, but unimaginable venture. I don't believe there are two living people who, each in their separate ways, are more devoted to me than she and Montagu: and it is the way of fortune that they two should combine to deal a death-blow to me."

Asquith then went on to assess Venetia's choice as husband including: "I am really fond of him, recognise his intellectual merits, find him excellent company and have always been able to reckon on his loyalty and devotion. Anything but this! It is not merely the prohibitive physical side (bad as that is) - I won't say anything about race and religion though they are not quite negligible factors. But he is not a man: a shamble of words and nerves and symptoms, intensely self absorbed, and - but I won't go on with the dismal catalogue." (90)

Violet Asquith was also upset by the news: "Curious and disturbing news reached us on Wednesday evening of Montagu's engagement to Venetia... Montagu's physical repulsiveness to me is such that I would lightly leap from the top story of Queen Anne's Mansions - or the Eiffel Tower itself to avoid the lightest contact - the thought of any erotic amenities with him is enough to freeze one's blood. Apart from this he is not only very unlike and Englishman - or indeed a European - but also extraordinarily unlike a man... He has no robustness, virility, courage, physical competency - he is devoured by hypochondria - which if it does not spring from a diseased body must indicate a very unhealthy mind." (91)

Margot Asquith was pleased the relationship was over. She told her daughter: "That want of candour in Venetia is what has hurt him but she has suffered tortures of remorse poor darling and I feel sorry for her... He is wonderful over it all - courageous, convinced and very humble. They were both old enough to know their own minds and no one must tease them now. There's a good deal of bosh in the religion campaign, though superficially it takes one in... It is Montagu's physique that I could never get over not his religion". (92)

The marriage between Venetia Stanley and Edwin Montagu took place on 26th July 1915, a few days after she had been received into the Jewish faith. Montagu's old friend from university, Raymond Asquith, defended the marriage: "I am entirely in favour of the Stanley/Montagu match. (i) Because for a woman any marriage is better than perpetual virginity, which after a certain age (not very far distant in Venetia's case) becomes insufferably absurd. (ii) Because, as you say yourself, she has had a fair chance of conceiving a romantic passion for someone or other during the last 12 years and has not done so and is probably incapable of doing so. This being so I think she is well advised to make a marriage of convenience. (iii) Because, in my opinion, this is a marriage of convenience. If a man has private means and private parts (specially if both are large) he is a convenience to a woman. (iv) Because it annoys Lord and Lady Sheffield. (v) Because it profoundly shocks the entire Christian community." (93)

In 1915 Sylvia Henley's husband, Anthony Morton Henley, was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and joined the staff of General John French, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front. Sylvia complained about his lack of letters and after Venetia's marriage to Edwin Montagu, she took over as Asquith's main confidante. Margot Asquith actually encouraged the relationship and she thought it would help her husband deal with losing Venetia. However, his daughter, Violet Asquith, did not agree as she "sensed a new, more dangerous challenge to her father's affections". (94)

Sylvia Henley kept her husband informed about Asquith's growing affection for her. She wrote to him about a weekend she spent at Asquith's house. "As we went to bed, the PM said he must show me his room. I was rather against this, as his affectionate nature gets the better of his wisdom, as you know. But there was no gainsaying him. We were standing talking, his arm around me, of books... I knew for certain he would exact a kiss from me, and knowing this I was glad it should be one of sympathy for that part of his life that I know about. And I told him how much love and sympathy I felt for him and kissed him - he can't do without affection... To me it is always a blot that the PM cannot like one without the physical side coming in so much. I should like him so much better if he held my hand and did not paw so much." (95)

In another letter later that month Sylvia told her husband that Venetia was upset that Asquith had turned his affections to her: "I am certain it cuts her to see the PM is fond of me." He began to take her out in his car and she claimed that she was able to "cajole the PM out of his sullen mood". Sylvia told her husband she was doing her "patriotic duty" in consoling Asquith: "He is now very fond of me in just the most wonderfully nice way. I hope our relations will never change." (96) On 2nd June 1915, Asquith told Sylvia: "You are my anchor and I love you and need you." (97)

Sylvia had to constantly fend off his physical approaches, such as kissing or enveloping arms. She told him that she loved being with him she did not want it to become a sexual relationship. Sylvia insisted "that so long as it remained platonic there was nothing I wanted more, but as soon as I felt there was a danger of that form of love giving place to the other - it must be all over." (98) Asquith replied that "an erotic adventure was never my idea". (99)

The Battle of the Somme

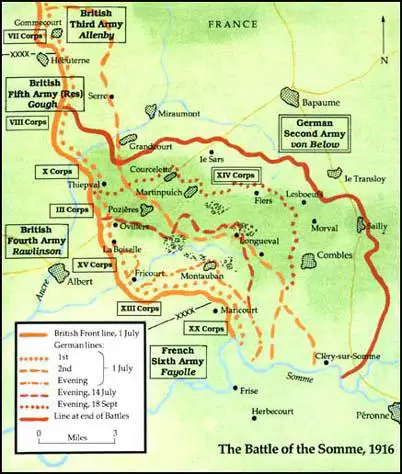

The Battle of the Somme was planned as a joint French and British operation. The idea originally came from the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre and was accepted by General Douglas Haig, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commander, despite his preference for a large attack in Flanders. Although Joffre was concerned with territorial gain, it was also an attempt to destroy German manpower.

Morale in Britain was at an all-time low. "Haig needed a breakthrough to boost the flagging spirits of a country still in principle fully behind the war, patriotic and pressing for military victory." After a meeting with the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre, it was decided to mount a joint offensive where the British and French lines joined on the Western Front. (100) According to Basil Liddell Hart, the decision by Joffre to make this sector, considered to be the German's strongest, "seems to have been arrived at solely because the British would be bound to take part in it." (101)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, was told about the plan when he visited General Haig in May 1916. He agreed to give his full support in his newspapers to the offensive. One of his biographers, S. J. Taylor, points out: "Northcliffe... at last capitulated, the Daily Mail descending into the propagandistic prose that came to characterize the reporting of the First World War. It was a style long since adopted by his competitors; stirring phrases, empty words, palpable lies." (102)

At first Joffre intended for to use mainly French soldiers but the German attack on Verdun in February 1916, turned the Somme offensive into a large-scale British diversionary attack. General Haig now took over responsibility for the operation and with the help of General Sir Henry Rawlinson, came up with his own plan of attack. Haig's strategy was for a eight-day preliminary bombardment that he believed would completely destroy the German forward defences. He told his General Staff that "the advance was to be pressed eastward far enough to enable our cavalry to push through into the open country beyond the enemy's prepared lines of defence." (103)

General Haig wrote that he was convinced that the offensive would win the war: "I feel that every step in my plan has been taken with the Divine help". (104) General Henry Rawlinson was was in charge of the main attack and his Fourth Army were expected to advance towards Bapaume. To the north of Rawlinson, General Edmund Allenby and the British Third Army were ordered to make a breakthrough with cavalry standing by to exploit the gap that was expected to appear in the German front-line. Further south, General Émile Fayolle was to advance with the French Sixth Army towards Combles. Rawlinson wrote: "DG (Haig) tells me that we are to attack, that the French are doing likewise and making a supreme effort. It will cost us dearly, and we shall not get very far." (105)

The Battle of the Somme began in early hours of the 1st July 1916, when nearly a quarter of a million shells were fired at the German positions in just over an hour, an average of 3,500 a minute. So intense was the barrage that it was heard in London. At 7.28 a.m. ten mines were exploded under the German trenches. Two minutes later, British and French troops attacked along a 25-mile front. The main objective was "to break through the German lines by means of a massive infantry assault, to try to create the conditions in which cavalry could then move forward rapidly to exploit the breakthrough." (106)

On the first day of the battle thirteen British divisions went "over the top" in regular waves. The bombardment failed to destroy either the barbed-wire or the concrete bunkers protecting the German soldiers. This meant that the Germans were able to exploit their good defensive positions on higher ground. "The attack was a total failure. The barrage did not obliterate the Germans. Their machine guns knocked the British over in rows: 19,000 killed, 57,000 casualties sustained - the greatest loss in a single day ever suffered by a British army and the greatest suffered by any army in the First World War. Haig had talked beforehand of breaking off the offensive if it were not at once successful. Now he set his teeth and kept doggedly on - or rather, the men kept on for him." (107)

Haig was helped in this by newspapers reporting that the offensive was a success. William Beach Thomas, in The Daily Mail, under the headline, "Enemy Outgunned", wrote: "We are laying siege not to a place but to the German Army - that great engine which had at last mounted to its final perfection and utter lust of dominion. In the first battle, we have beaten the Germans by greater dash in the infantry and vastly superior weight in munitions." (108) In a later report he claimed: The very attitudes of the dead, fallen eagerly forwards, have the look of expectant hope. You would say they died with the light of victory in their eyes." (109)

General Douglas Haig continued to order further attacks on German positions at the Somme and on the 13th November the British Army captured the fortress at Beaumont Hamel. However, heavy snow forced Haig to abandon his gains. With the winter weather deteriorating Haig now brought an end to the Somme offensive. Since the 1st July, the British has suffered 420,000 casualties. The French lost nearly 200,000 and it is estimated that German casualties were in the region of 500,000. Allied forces gained some land but it reached only 12km at its deepest points. Despite mounting criticism over his seeming disregard of British lives, Haig survived as Commander-in-Chief. One of the main reasons for this was the support he received from Northcliffe's newspapers. (110)

General William Robertson continued to support Haig's tactics. Robertson's biographer, David R. Woodward, has pointed out: "British losses on the first day of the Somme offensive - almost 60,000 casualties - shocked Robertson. Haig's one-step breakthrough attempt was the antithesis of Robertson's cautious approach of exhausting the enemy with artillery and limited advances. Although he secretly discussed more prudent tactics with Haig's subordinates he defended the BEF's operations in London. The British offensive, despite its limited results, was having a positive effect in conjunction with the other allied attacks under way against the central powers. The continuation of Haig's offensive into the autumn, however, was not so easy to justify." (111)

Haig was not disheartened by these heavy losses on the first day and ordered General Sir Henry Rawlinson to continue making attacks on the German front-line. A night attack on 13th July did achieve a temporary breakthrough but German reinforcements arrived in time to close the gap. Haig believed that the Germans were close to the point of exhaustion and continued to order further attacks expected each one to achieve victory. Although small gains were achieved, for example, the capture of Pozieres on 23rd July, they could not be successfully followed up.

Captain Charles Hudson was one of those officers who took part in the battle. He later wrote: "It is difficult to see how Haig, as Commander-in-Chief living in the atmosphere he did, so divorced from the fighting troops, could fulfil the tremendous task that was laid upon him effectively. I did not believe then, and I do not believe now that the enormous casualties were justified. Throughout the war huge bombardments failed again and again yet we persisted in employing the same hopeless method of attack. Many other methods were possible, some were in fact used but only half-heartedly." (112)

Private James Lovegrove was also highly critical of Haig's tactics: "The military commanders had no respect for human life. General Douglas Haig... cared nothing about casualties. Of course, he was carrying out government policy, because after the war he was knighted and given a lump sum and a massive life-pension. I blame the public schools who bred these ego maniacs. They should never have been in charge of men. Never."

Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985), has argued that Brigadier-General John Charteris, the Chief Intelligence Officer at GHQ. was partly responsible for this disaster: "Charteris's intelligence reports throughout the five-month battle were designed to maintain Haig's morale. Though one of the intelligence officer's duties may be to help maintain his commander's morale, Charteris crossed the frontier between optimism and delusion." As late as September 1916, Charteris was telling General Haig: "It is possible that the Germans may collapse before the end of the year." (113)

On 15th September General Alfred Micheler and the Tenth Army joined the battle in the south at Flers-Courcelette. Despite using tanks for the first time, Micheler's 12 divisions gained only a few kilometres. Whenever the weather was appropriate, General Sir Douglas Haig ordered further attacks on German positions at the Somme and on the 13th November the BEF captured the fortress at Beaumont Hamel. However, heavy snow forced Haig to abandon his gains.

With the winter weather deteriorating Haig now brought an end to the Somme offensive. Since the 1st July, the British has suffered 420,000 casualties. The French lost nearly 200,000 and it is estimated that German casualties were in the region of 500,000. Allied forces gained some land but it reached only 12km at its deepest points. Haig wrote at the time: "The results of the Somme fully justify confidence in our ability to master the enemy's power of resistance." (114)

During the First World War a total of 634 awards of the Victoria Cross were made, of which fifty-one were for the Battle of the Somme. "The spread of ranks who won the medal is a fairly wide one, with twenty going to officers, twelve to non-commissioned officers, and nineteen going to privates or their equivalent... A third of the Somme VCs were awarded posthumously and only thirty-three men survived the war." (115)

In the 1920s Haig was severely criticised for the tactics used at offensives such as the one at the Somme. This included the prime minister of the time, David Lloyd George: "It is not too much to say that when the Great War broke out our Generals had the most important lessons of their art to learn. Before they began they had much to unlearn. Their brains were cluttered with useless lumber, packed in every niche and corner. Some of it was never cleared out to the end of the War. They knew nothing except by hearsay about the actual fighting of a battle under modern conditions. Haig ordered many bloody battles in this War. He only took part in two. He never even saw the ground on which his greatest battles were fought, either before or during the fight. The tale of these battles constitutes a trilogy, illustrating the unquestionable heroism that will never accept defeat and the inexhaustible vanity that will never admit a mistake." (116)

Duff Cooper, who was commissioned by the Haig family to write his official biography, argued: "There are still those who argue that the Battle of the Somme should never have been fought and that the gains were not commensurate with the sacrifice. There exists no yardstick for the measurement of such events, there are no returns to prove whether life has been sold at its market value. There are some who from their manner of reasoning would appear to believe that no battle is worth fighting unless it produces an immediately decisive result which is as foolish as it would be to argue that in a prize fight no blow is worth delivering save the one that knocks the opponent out. As to whether it were wise or foolish to give battle on the Somme on the first of July, 1916, there can surely be only one opinion. To have refused to fight then and there would have meant the abandonment of Verdun to its fate and the breakdown of the co-operation with the French." (117)

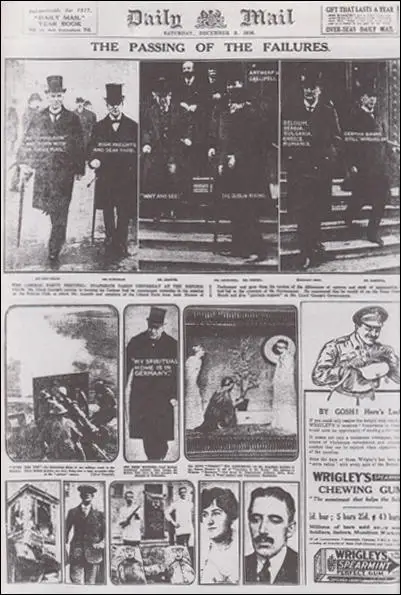

The Overthrow of H. H. Asquith

At a meeting in Paris on 4th November, 1916, David Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lloyd George agreed with Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, that he should talk to Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, about the situation. Bonar Law remained loyal to Asquith and so Lloyd George contacted Max Aitken instead and told him about his suggested reforms.

Lord Northcliffe joined with Lloyd George in attempting to persuade H. H. Asquith and several of his cabinet, including Sir Edward Grey, Arthur Balfour, Robert Crewe-Milnes, 1st Marquess of Crewe and Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, to resign. It was reported that Lloyd George was trying to encourage Asquith to establish a small War Council to run the war and if he did not agree he would resign. (118)

Tom Clarke, the news editor of The Daily Mail, claims that Lord Northcliffe told him to take a message to the editor, Thomas Marlowe, that he was to run an article on the political crisis with the headline, "Asquith a National Danger". According to Clarke, Marlowe "put the brake on the Chief's impetuosity" and instead used the headline "The Limpets: A National Danger". He also told Clarke to print pictures of Lloyd George and Asquith side by side: "Get a smiling picture of Lloyd George and get the worst possible picture of Asquith." Clarke told Northcliffe that this was "rather unkind, to say the least". Northcliffe replied: "Rough methods are needed if we are not to lose the war... it's the only way." (119)

Those newspapers that supported the Liberal Party, became concerned that a leading supporter of the Conservative Party should be urging Asquith to resign. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of The Daily News, objected to Lord Northcliffe's campaign against Asquith: "If the present Government falls, it will fall because Lord Northcliffe decreed that it should fall, and the Government that takes its place, no matter who compose it, will enter on its task as the tributary of Lord Northcliffe." (120)

Asquith was in great difficulty but he did have Cabinet ministers who did not want Lloyd George as prime minister. Roy Jenkins has argued that he should have had a meeting with "Cecil, Chamberlain, Curzon and Long might have had considerable effect. To begin with, he would no doubt have found them wavering. But he was not without influence over them. In the course of the discussion their doubts about Lloyd George would have come to the surface, and the conclusion might have been that they would have stiffened Asquith, and he would have stiffened them." (121) Lloyd George's biographer, John Grigg, disagrees with Jenkins. His research suggests that Asquith had very little support from Conservative Party members of the coalition government and if he had tried to use them against Lloyd George it would end in failure. (122)

On 4th December, 1916, The Times praised Lloyd George's stand against the present "cumbrous methods of directing the war" and urged Asquith to accept the "alternative scheme" of the small War Council, that he had proposed. Asquith should not be a member of the council and instead his qualities were "fitted better... to preserve the unity of the Nation". (123) Even the Liberal Party supporting Manchester Guardian, referred to the humiliation of Asquith, whose "natural course would be either to resist the demand for a War Council, which would partly supersede him as Premier, or alternatively himself to resign." (124)

Asquith came to the conclusion that Lloyd George had leaked embarrassing details of the conversation he had with Lloyd George, including the threat of resignation if he did not get what he wanted. That night he sent a note to Lloyd George: "Such productions as the leading article in today's Times, showing the infinite possibilities for misunderstanding and misrepresentation of such an arrangement as we discussed yesterday, make me at least doubtful of its feasibility. Unless the impression is at once corrected that I am being relegated to the position of an irresponsible spectator of the War, I cannot go on." (125)

Lloyd George denied the charge of leaking information but admitted that Lord Northcliffe wanted to "smash" his government. However, he went on to argue that Northcliffe also wanted to hurt him and had to put up with his newspaper's "misrepresentations... for months". He added "Northcliffe would like to make this (the formation of a small War Committee) and any other arrangement under your Premiership impossible... I cannot restrain nor I fear influence Northcliffe." (126)