Sylvia Henley

Sylvia Stanley was born on 19th March, 1882. She was one of the seven children to survive to adulthood of Edward Lyulph Stanley, who succeeded as fourth Baron Stanley of Alderley in 1903 and Mary Bell Stanley. The family lived at Alderley Park, a rambling early nineteenth-century house, near Macclesfield, Cheshire. (1)

Sylvia was encouraged to take an interest in politics and as a teenager could offer friends a family stimulating conversation. The family also discussed religion. Baron Stanley was a freethinker and according to Bertrand Russell he argued that Christianity was usually "a faith held by inheritance" but he insisted that "faith should be held only by conviction." (2)

Sylvia's brother, Arthur Stanley, became the Liberal Party MP for the seat of Eddisbury in Cheshire. It was her brother who introduced her to Anthony Morton Henley. He was a regular visitor to Alderley Park and was "always ready to inject light-hearted banter into the sometimes overheated Stanley family gatherings". Sylvia Stanley married Captain Henley on 24th April, 1906. (3)

In 1907 Sylvia's sister, Venetia Stanley, became close friends with Violet Asquith, the daughter of H. H. Asquith, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who two years later was to become the British prime minister. In their letters Venetia and Violet constantly professed undying love for one another. Violet also sent her presents:"I’ve sent you a tiny and very humble gift which you must wear always (in your bath and in your bed) and if you think it too ugly you may tuck it in under your combies." (4)

Venetia Stanley and H. H. Asquith

Venetia accompanied Violet and her father on a trip to Sicily in 1912. Also on holiday with them was the young Liberal Party MP, Edwin Montagu. Over the next two weeks both men fell in love with Venetia. Asquith, was 59 years old at the time and in a letter to her later he described the holiday as "the first stage in our intimacy... we had together one of the most interesting and delightful fortnights in all our lives... the scales dropped from my eyes… and I dimly felt… that I had come to a turning point in my life". (5)

On their return from holiday Asquith invited Venetia to a house party, following this up with invitations to 10 Downing Street. However, he was unaware that Montagu was also besotted with Venetia. He wrote to her regularly and took her out whenever he could. It seems that Asquith was totally unaware of this developing relationship. In August 1912 he asked her to marry him. At first she accepted the proposal and later changed her mind. (6)

If Venetia accepted his proposal he would have lost his inheritance as his father, Samuel Montagu, 1st Baron Swaythling, who had died in 1911, had stipulated in his will that he had to marry a Jewish woman. "Although Venetia, physically repelled by his huge head and course pock-marked face, refused him, she lapped up the waspish political gossip at which he excelled, and they continued to see a great deal of one another, with Montagu a regular house guest at the Stanley family homes at Alderley and Penrhos." (7)

In 1913 Asquith began to write to Venetia Stanley on a regular basis and would meet her in London as often as possible. She admitted to Edwin Montagu: "It was delicious seeing him again... He was in very good spirits I thought in spite of the crisis (over Ireland). He didn't, as you can imagine, talk much about it and our conversation ran in very well worn lines, the sort that he enjoys on these occasions and which irritate Margot so much by their great dreariness. I love every well known word of them - with and for me familiarity in a large part of the charm." (8)

There are several accounts of Asquith attempting to seduce young women in his company. Diana Cooper complained that on several occasions she had to defend her face "from his fumbly hands and mouth". (9) The Asquith family were fully aware of his inappropriate behaviour. His daughter-in-law, Cynthia Asquith, wrote about it in her diary but according to her biographer, Nicola Beauman, she was forced to "ink over all references in her diary". Ottoline Morrell was another woman who complained about his behaviour. Apparently she told Lytton Strachey that Asquith "would take a lady's hand, as she sat beside him on the sofa, and make her feel his erected instrument under his trousers". (10)

Sylvia Henley also complained about Asquith and commented that if she ever found herself alone with Asquith, "it was safest to sit either side of the fire... or to make sure there was a table between them." Another woman recalled an incident when "the Prime Minister had his head jammed down in to my shoulder and all my fingers in his mouth." (11) Henley's relationship with Asquith helped her husband's career as he was appointed the prime minister's private secretary. (12)

Edwin Montagu

On 30th March, 1915, Asquith wrote to Venetia four times. Disturbed by his intense love of her she decided to bring an end to the relationship by marrying Edwin Montague. He had recently joined the cabinet as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. John Grigg has pointed out: "Still only in his middle thirties, he had risen in politics as Asquith's protégé but was far from being a mere hanger-on... Rich and privileged, intellectually a late-developer, sensitive and emotional yet capable of a certain ruthlessness, he was now becoming a rather important figure." (13)

Montagu now had status as well as money. Venetia Stanley decided to accept his proposal of marriage. "For Montagu, religion was a purely personal affair; he had no formal religious beliefs, was anti-Zionist, and constantly emphasized his foremost identity as a Briton". However, in order that Montagu could continue to receive an annual income of £10,000 from his father's estate, Venetia was compelled to convert to Judaism. (14)

On 12th May 1915, Asquith was shocked and appalled to receive Venetia's letter announcing her engagement to the man who he recently appointed as his Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Asquith replied that this news "breaks my heart" and that he "couldn't bear to come and see you". (15)

On the day he heard the news Asquith wrote three letters to Sylvia Henley, about the proposed marriage. In the second letter he pointed out: "I had never any illusions, and often told Venetia: and she also was always most frank about her someday getting married. But this. We have always treated it as a kind of freakish, but unimaginable venture. I don't believe there are two living people who, each in their separate ways, are more devoted to me than she and Montagu: and it is the way of fortune that they two should combine to deal a death-blow to me."

Asquith then went on to assess Venetia's choice as husband including: "I am really fond of him, recognise his intellectual merits, find him excellent company and have always been able to reckon on his loyalty and devotion. Anything but this! It is not merely the prohibitive physical side (bad as that is) - I won't say anything about race and religion though they are not quite negligible factors. But he is not a man: a shamble of words and nerves and symptoms, intensely self absorbed, and - but I won't go on with the dismal catalogue." (16)

Violet Asquith was also upset by the news: "Curious and disturbing news reached us on Wednesday evening of Montagu's engagement to Venetia... Montagu's physical repulsiveness to me is such that I would lightly leap from the top story of Queen Anne's Mansions - or the Eiffel Tower itself to avoid the lightest contact - the thought of any erotic amenities with him is enough to freeze one's blood. Apart from this he is not only very unlike and Englishman - or indeed a European - but also extraordinarily unlike a man... He has no robustness, virility, courage, physical competency - he is devoured by hypochondria - which if it does not spring from a diseased body must indicate a very unhealthy mind." (17)

Margot Asquith was pleased the relationship was over. She told her daughter: "That want of candour in Venetia is what has hurt him but she has suffered tortures of remorse poor darling and I feel sorry for her... He is wonderful over it all - courageous, convinced and very humble. They were both old enough to know their own minds and no one must tease them now. There's a good deal of bosh in the religion campaign, though superficially it takes one in... It is Montagu's physique that I could never get over not his religion". (18)

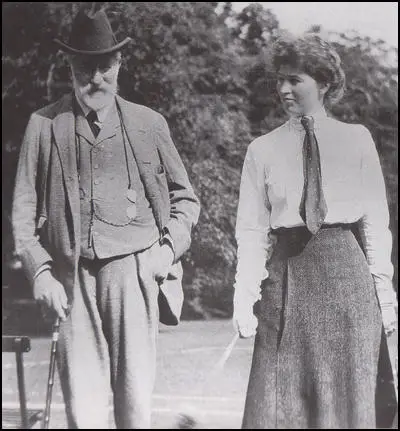

Sylvia Henley and H. H. Asquith

In 1915 Sylvia's husband was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and joined the staff of General John French, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front. Sylvia complained about his lack of letters and after his sister's marriage to Edwin Montagu, she took over as Asquith's main confidante. Margot Asquith actually encouraged the relationship and she thought it would help her husband deal with losing Venetia. However, his daughter, Violet Asquith, did not agree as she "sensed a new, more dangerous challenge to her father's affections". (19)

Sylvia kept her husband informed about Asquith's growing affection for her. She wrote to him about a weekend she spent at Asquith's house. "As we went to bed, the PM said he must show me his room. I was rather against this, as his affectionate nature gets the better of his wisdom, as you know. But there was no gainsaying him. We were standing talking, his arm around me, of books... I knew for certain he would exact a kiss from me, and knowing this I was glad it should be one of sympathy for that part of his life that I know about. And I told him how much love and sympathy I felt for him and kissed him - he can't do without affection... To me it is always a blot that the PM cannot like one without the physical side coming in so much. I should like him so much better if he held my hand and did not paw so much." (20)

In another letter later that month Sylvia told her husband that Venetia was upset that Asquith had turned his affections to her: "I am certain it cuts her to see the PM is fond of me." He began to take her out in his car and she claimed that she was able to "cajole the PM out of his sullen mood". Sylvia told her husband she was doing her "patriotic duty" in consoling Asquith: "He is now very fond of me in just the most wonderfully nice way. I hope our relations will never change." (21) On 2nd June 1915, Asquith told Sylvia: "You are my anchor and I love you and need you." (22)

Sylvia had to constantly fend off his physical approaches, such as kissing or enveloping arms. She told him that she loved being with him she did not want it to become a sexual relationship. Sylvia insisted "that so long as it remained platonic there was nothing I wanted more, but as soon as I felt there was a danger of that form of love giving place to the other - it must be all over." (23) Asquith replied that "an erotic adventure was never my idea". (24)

Knowing that Sylvia had the ear of Asquith, she received house calls from irate wives of politicians axed in government reshuffles. This included a visit from her cousin, Clementine Churchill, after Winston Churchill had been replaced by Arthur Balfour, as First Lord of the Admiralty. Clementine was so angry that she told Sylvia that she wanted to "dance on his (Asquith's) grave." (25)

Asquith wrote to Sylvia every day and expected her to do the same. He urged her to "go on loving me dearest, it makes so much difference". He told Sylvia that he needed to hear from her "every day" and that he always "counted the hours" between letters. In one letter he asked her to "think of me always, every day, if possible at all hours of the day". In his all-consuming passion, he visualised her constantly. "How clearly I have before me now your face. I only hope and pray that it may come to me in my dreams." (26)

Sylvia warned him about the state secrets he was including in his letters. He replied: "What a heavenly team we are together despite your criticisms (about writing letters at War Councils) and your warnings (about limits!), I can't tell you what a supreme delight it is to me, to come to you and sit beside you and confide things to you"and to feel that the wisest of women is near me - and really loves me! I believe you do; and you don't know or imagine how much I love you." (27)

Sylvia also attempted to promote her husband's career and went on a car drive with General William Robertson where she argued that he should be given an active field command. However, she constantly complained about Henley's lack of letters from France. This turned to fury when she discovered that he was writing regularly to her sister, Venetia. She demanded to see the letters, but Venetia refused, but she did tell her that Henley had used the words "I long to be with you". Sylvia wrote to her husband: "I see you're so false, telling me I am everything to you. And now I know that as you said it, you were longing to be with her and not me." (28)

Sylvia Henley warned her husband that she would allow herself to get even closer to Asquith: "A rudderless ship is so easily blown onto a sea shore". When she told Asquith about the situation he gave her a ring and tried to persuade her to wear it on the little finger on her right hand. Venetia continued to write intimate letters to Anthony Morton Henley. This included a reference to meeting at a hotel at Folkestone on 12th July, 1915. (29)

H. H. Asquith had also developed other close relationships with other women during this period. These women were usually "married and therefore convention allowed close friendships to flourish with the opposite sex". (30) This included the actress, Viola Tree, Pamela McKenna, the wife of the cabinet member, Reginald McKenna, the sculptress Kathleen Scott, Christabel McLaren (later Lady Aberconway) and Hilda Harrison, whose husband had been killed during the First World War. (31)

By the winter of 1915 Sylvia Henley had became even more important to Asquith. The main reason for this was that he was now under considerable pressure from the newspapers over the way he was leading the nation during the First World War. This included his reluctance to introduce conscription and the Zeppelin Bombing Raids, that killed 277 and wounded 645 civilians during that year. (32)

Sylvia was also deeply concerned about her relationship with her husband. "I have allowed my thoughts to wander back to what is behind and to speculate as to what is to come to us. It will always be a sorrow to me to give you up as my intimate lover. To give up the entire possession of you, but I am, I think, sensible enough to realise that it isn't a relationship which can be eternal, and I am now prepared to accept a compromise. I have showed you how deeply and passionately I can love you, and how you can be so much the centre of my life, that all else is eclipsed. But such a love must be exacting and that makes life rather difficult, especially to a man of your temperament." (33)

Stories about Asquith's behaviour towards young women continued to circulate. The campaigner for women's rights, Ethel Smyth, wrote to Randall Thomas Davidson, the Archbishop of Canterbury: "It is disgraceful that millions of women shall be trampled underfoot because of the convictions of an old man who notoriously can't be left alone in a room with a young girl after dinner". (34) Duff Cooper also commented that whereas Asquith was "oblivious of young men" he was "lecherous of young women". (35)

Overthrow of H. H. Asquith

In November 1916, David Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lloyd George agreed with Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, that he should talk to Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, about the situation. Bonar Law remained loyal to Asquith and so Lloyd George contacted Max Aitken instead and told him about his suggested reforms.

Lord Northcliffe joined with Lloyd George in attempting to persuade Asquith and several of his cabinet, including Sir Edward Grey, Arthur Balfour, Robert Crewe-Milnes, 1st Marquess of Crewe and Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, to resign. It was reported that Lloyd George was trying to encourage Asquith to establish a small War Council to run the war and if he did not agree he would resign. (36)

Tom Clarke, the news editor of The Daily Mail, claims that Lord Northcliffe told him to take a message to the editor, Thomas Marlowe, that he was to run an article on the political crisis with the headline, "Asquith a National Danger". According to Clarke, Marlowe "put the brake on the Chief's impetuosity" and instead used the headline "The Limpets: A National Danger". He also told Clarke to print pictures of Lloyd George and Asquith side by side: "Get a smiling picture of Lloyd George and get the worst possible picture of Asquith." Clarke told Northcliffe that this was "rather unkind, to say the least". Northcliffe replied: "Rough methods are needed if we are not to lose the war... it's the only way." (37)

On 4th December, 1916, The Times praised Lloyd George's stand against the present "cumbrous methods of directing the war" and urged Asquith to accept the "alternative scheme" of the small War Council, that he had proposed. Asquith should not be a member of the council and instead his qualities were "fitted better... to preserve the unity of the Nation". (38) Even the Liberal Party supporting Manchester Guardian, referred to the humiliation of Asquith, whose "natural course would be either to resist the demand for a War Council, which would partly supersede him as Premier, or alternatively himself to resign." (39)

At a Cabinet meeting the following day, Asquith refused to form a new War Council that did not include him. Edwin Montagu suggested that King George V should be asked to call Asquith, Lloyd George, Andrew Bonar Law (leader of the Conservative Party) and Arthur Henderson (leader of the Labour Party) together to find a solution. Lloyd George refused and instead resigned. (40)

Lloyd George announced: "It is with great personal regret that I have come to this conclusion.... Nothing would have induced me to part now except an overwhelming sense that the course of action which has been pursued has put the country - and not merely the country, but throughout the world the principles for which you and I have always stood throughout our political lives - is the greatest peril that has ever overtaken them. As I am fully conscious of the importance of preserving national unity, I propose to give your Government complete support in the vigorous prosecution of the war; but unity without action is nothing but futile carnage, and I cannot be responsible for that." (41)

Conservative members of the coalition made it clear that they would no longer be willing to serve under Asquith. At 7 p.m. he drove to Buckingham Palace and tendered his resignation to King George V. Apparently, he told J. H. Thomas, that on "the advice of close friends that it was impossible for Lloyd George to form a Cabinet" and believed that "the King would send for him before the day was out." Thomas replied "I, wanting him to continue, pointed out that this advice was sheer madness." (42)

Writing to Sylvia Henley the day after his resignation Asquith confessed "to feeling a certain sense of relief" now he was out of office. (43) Sylvia continued to be a sounding board for Asquith, however, he seemed to lose interest in her as she became heavily pregnant. She was disappointed when she gave birth to a third girl. "It is no good moping and I only hope next time will bring us what we want so much." (44)

Final Years

Brigadier-General Anthony Morton Henley was heavily involved in the breakthrough of the Hindenburg Line on 27th September, 1918. His brigade continued fighting almost up to the Armistice. Henley finished the war having been mentioned in dispatches eight times. In 1919 he was awarded the Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George. Sylvia's brother, Oliver Stanley, also survived the war, although he wounded three times. The family was lucky as nearly 20 per cent of serving peers under 50 years of age being killed in action. (45)

Henley died of a heart attack, aged 51, in 1925. Sylvia Henley continued to see H. H. Asquith until his death on 15th February 1928. The family home of Alderley Park was destroyed by fire in 1931 and the 4,500-acre estate was sold. During the Second World War, as she was an old friend of Winston Churchill, she was a regular visitor to 10 Downing Street.

Sylvia Henley died of a heart attack, aged 98, on 18th May, 1980.

Primary Sources

(1) Sylvia Henley, letter to Anthony Morton Henley (9th May, 1915)

As we went to bed, the PM said he must show me his room. I was rather against this, as his affectionate nature gets the better of his wisdom, as you know. But there was no gainsaying him. We were standing talking, his arm around me, of books... I knew for certain he would exact a kiss from me, and knowing this I was glad it should be one of sympathy for that part of his life that I know about. And I told him how much love and sympathy I felt for him and kissed him - he can't do without affection... To me it is always a blot that the PM cannot like one without the physical side coming in so much. I should like him so much better if he held my hand and did not paw so much.

(2) H. H. Asquith, letter to Sylvia Henley (12th May, 1915)

Since I wrote to you this morning I have gone through a Cabinet, a luncheon with Prince Paul of Serbia and Sir R. McBride of British Columbia and a rather searching question time at the House and I hope I got through them all without any sign of disquietude or impotence. All the same, I don't suppose there is in the kingdom at this moment a much more unhappy man.

I had never any illusions, and often told Venetia: and she also was always most frank about her someday getting married. But this. We have always treated it as a kind of freakish, but unimaginable venture. I don't believe there are two living people who, each in their separate ways, are more devoted to me than she and Montagu: and it is the way of fortune that they two should combine to deal a death-blow to me... I am really fond of him, recognise his intellectual merits, find him excellent company and have always been able to reckon on his loyalty and devotion. Anything but this!

It is not merely the prohibitive physical side (bad as that is) - I won't say anything about race and religion though they are not quite negligible factors. But he is not a man: a shamble of words and nerves and symptoms, intensely self absorbed, and - but I won't go on with the dismal catalogue...

She says at the end of a sadly meagre letter: "I can't help feeling, after all the joy you've given me, that mine is a very treacherous return". Poor darling: I wouldn't have put it like that. But in essence it is true: and it leaves me sore and humiliated.

Dearest Sylvia, I am almost ashamed to write to you like this, and I know you won't say a word to her of what I have written. But whom have I but you to turn to? in this searching trial, which comes upon me, when I am almost overwhelmed with every kind and degree of care and responsibility. Don't think that I am blaming her: I shall love her with all my heart to my dying day; she has given me untold happiness. I shall always bless her. But - I know you will understand. Send me a line of help and sympathy.

(3) John Preston, The Daily Mail (10th June, 2016)

While there’s no proof that they had a physical relationship, Venetia and Violet constantly professed undying love for one another, as well as sending each other little presents. "I’ve sent you a tiny and very humble gift which you must wear always (in your bath and in your bed)," wrote Violet, "and if you think it too ugly you may tuck it in under your combies."

So who was Venetia Stanley, the object of not only the Prime Minister’s affections, but his daughter’s, too? On the surface, she came from an impeccably conventional aristocratic family. Peer a little more closely, though, and what emerges is anything but conventional.

It seems quite possible that Venetia’s uncle may also have been her father. Certainly there were lots of rumours to that effect and her mother was known to have had an affair with her husband’s brother. Despite Venetia possessing what one friend of hers called "a gruff baritone voice", Asquith thought her the most alluring woman he’d ever met..

When Venetia announced her engagement to an extremely drippy man called Edwin Montagu - Secretary of State for India - the Prime Minister was heartbroken.

However, he didn’t repine for long, swiftly transferring his attentions to Venetia’s younger sister, Sylvia. Initially flattered, Sylvia soon discovered that if she was alone with Asquith, "it was safest to sit either side of the fire... or to make sure there was a table between them."

Not that she was the only object of his attentions. By today’s standards, Asquith was a serial groper. One woman recalled an incident when "the Prime Minister had his head jammed down in to my shoulder and all my fingers in his mouth"...

When Edwin died in 1924, Venetia literally took to the air, buying herself an airplane and whizzing around the Middle East with yet another of her lovers. By now some of her old friends, appalled by all this conjugal carnage, had given her up as a bad lot.

But not Winston Churchill and his wife, Clementine, who had always been fond of Venetia - she’d been a bridesmaid at their wedding. During World War II they regularly invited her to their weekend retreat at Ditchley Park in Oxfordshire.

(4) Sylvia Henley, letter to Anthony Morton Henley (23rd January, 1916)

I have allowed my thoughts to wander back to what is behind and to speculate as to what is to come to us. It will always be a sorrow to me to give you up as my intimate lover. To give up the entire possession of you, but I am, I think, sensible enough to realise that it isn't a relationship which can be eternal, and I am now prepared to accept a compromise. I have showed you how deeply and passionately I can love you, and how you can be so much the centre of my life, that all else is eclipsed. But such a love must be exacting and that makes life rather difficult, especially to a man of your temperament.

.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)