On this day on 10th November

On this day in 1697 William Hogarth was born. Hogarth's father opened a coffee-house in London but the venture was unsuccessful and in 1707 he was confined to Fleet Prison for debt. Hogarth was released five years later during an amnesty.

When Hogarth was sixteen he was apprenticed to Ellis Gamble, a silverplate engraver. By 1720 Hogarth had own business engraving book plates and painting portraits. Around this time Hogarth met the artist, Sir James Thornhill. Impressed by his history paintings, Hogarth made regular visits to Thornhill's free art academy in Covent Garden.

The two men became close friends and Hogarth eventually married Thornhill's daughter, Jane. During the 1720s Hogarth worked for the printseller, Philip Overton. Hogarth also started to produce political satires. In 1726 Hogarth published The Punishments of Lemuel Gulliver, a satire on the prime minister, Robert Walpole.

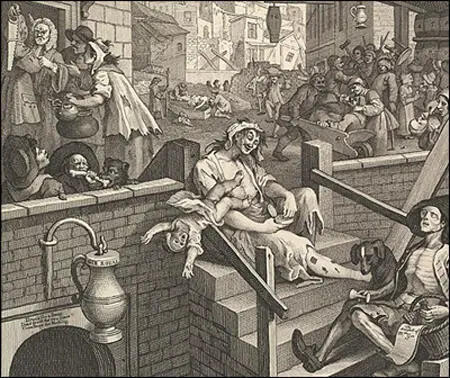

Hogarth also painted pictures that told a moral story. The first of these, The Harlot's Progress (1732), shows the downfall of a country girl at the hands of people living in London. Other examples of this approach included The Rake's Progress (1733-35) and Industry and Idleness (1747).

By the 1730s Hogarth was an established artist but he suffered from printsellers who used his work without paying royalties. In 1735 Hogarth manages to persuade his friends in Parliament to pass the Engravers' Copyright Act. Later that year, Hogarth established St. Martin's Lane Academy, a guild for professional artists and a school for young artists.

After a period painting portraits of the rich and famous, Hogarth returned in 1751 to producing prints of everyday life. Prints such as Beer Street, Gin Lane and the Four Stages of Cruelty were extremely popular and sold in large numbers.

In The Election Hogarth produced four pictures that illustrated the Oxfordshire parliamentary election of 1754. Taken together, the four paintings show the evolving sequence of events during election day. The first three paintings, Election Entertainment, Canvassing for Votes and The Polling provides details of the type of corruption that took place in 18th century elections. In the final painting, Chairing the Member the winning Tory candidate's supporters celebrate his victory.

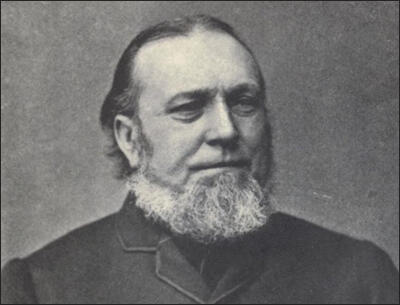

On this day in 1735 Granville Sharp was born. In 1765 Sharp was living with his brother, a surgeon in Wapping. One day Jonathan Strong, a black man, arrived at the house. Strong was a slave who had been so badly beaten by his master, David Lisle, that he was close to death. Sharp took Strong to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, where he had to spend four months recovering from his injuries. Strong told Sharp how Lisle, had brought him to England from Barbados. Lisle had apparently been dissatisfied with Strong's services and after beating him with his pistol, had thrown him onto the streets.

After Jonathan Strong had regained his health, David Lisle paid two men to recapture him. When Sharp heard the news he took Lisle to court claiming that as Strong was in England he was no longer a slave. However, it was not until 1768 that the courts ruled in Strong's favour. The case received national publicity and Sharp was able to use this in his campaign against slavery.

Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997) has pointed out: "Sharp put this matter further to the test in the case of the slave Thomas Lewis, who, belonging to a West Indian planter, escaped in Chelsea. When he was recaptured, and shipped to begin the journey to Jamaica, Sharp served the captain on his boat with a writ of habeas corpus. The case came before Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, who put to the jury the question whether the master had established his claim to the slave as his property. If they decided affirmatively, he would rule whether such a property could persist in England. The jury decided that the master had not established his claim. So the main question was left unsettled. Lord Mansfield said, rather curiously, that he hoped that the question whether slaves could be forcibly shipped back to the plantations would never be discussed."

In 1769 Sharp published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery. Soon afterwards he began to correspond and collaborate with the Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet and the Philadelphia abolitionist Benjamin Rush. He also took up the cases of other slaves such as James Somersett, and convinced the courts that "as soon as any slave sets foot upon English territory, he becomes free."

Granville Sharp developed radical political opinions about other issues as well. He argued in favour of parliamentary reform and an increase in the low wages paid to farm labourers. Sharp also supported the American colonists against the British government and as a result, had to resign from the civil service in 1776.

In April 1780 John Cartwright helped establish the Society for Constitutional Information. Granville Sharp joined the organisation. Other members included John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Gales and William Smith. It was an organisation of social reformers, many of whom were drawn from the rational dissenting community, dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties. It promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform. Sharp's biographer, Grayson Ditchfield, has pointed out that "Sharp corresponded with Christopher Wyvill, John Jebb, and other reformers; he wrote strongly against triennial parliaments as an insufficient measure; and he supported the legislative independence of the Irish parliament. In the belief that the ancient constitution represented people rather than property, and as an alternative to the universal suffrage for which he was not an enthusiast, Sharp advocated a revival of the Anglo-Saxon system of frankpledge. It would involve a system of administration from tithing courts to parliament, which would secure the involvement in government, and the preservation of the rights, of an active citizenry."

On this day in 1826 Joseph Arch, the son of a farm labourer, was born. After attending school for three years Joseph started work at the age of nine as a bird scarer on a local farm. Over the next few years he developed the skills of hedging, ditching and mowing.

On 3rd February, 1847, Arch married Mary Anne Mills, the daughter of a carpenter. A year later Arch became a Primitive Methodist lay preacher. In many of his sermons he dealt with the financial problems of farm labourers. He developed a reputation as a radical and in 1872 he was approached by a group of men who sought his help in forming a farm workers' union. Arch agreed to their request and during the next few months members increased rapidly. On 29th May, 1872, the National Agricultural Labourers' Union was established and Joseph Arch was elected as its full-time President. Within two years the union had over 86,000 members, over one-tenth of the farm work force in Britain.

The Canadian government invited Joseph Arch to visit its country in 1873 where he examined the suitability of the country for British emigration. Arch was impressed with what he saw and during the next few years the union helped over 40,000 farm labourers and their families to emigrate to Canada and Australia.

As well as trying to improve his members' pay and conditions, Arch also campaigned for the extension of the franchise. William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Government, was sympathetic to these demands and this resulted in the passing of he 1884 Parliamentary Reform Act.

In the 1885 General Election, Joseph Arch was elected as the Liberal Party MP for North-West Norfolk. Arch, the first agricultural labourer to be a member of the House of Commons. In 1893 Arch was appointed as a member of the Royal Commission on the Aged Poor. Arch retired from Parliament before the 1900 General Election.

On this day in 1836 Mary Grant got married, in Kingston to Edwin Horatio Seacole, but she was soon widowed. According to her biographer, Alan Palmer: "With her sister, Louisa, she ran the family boarding-house for several years, supervising its reconstruction after Kingston's great fire in 1843. She nursed cases of cholera and yellow fever in Jamaica and at Las Cruces in Panama where, for more than two years, she helped her brother manage a hotel. On returning to Jamaica she was briefly nursing superintendent at Up-Park military camp."

In 1850 Kingston was hit by a cholera epidemic. Mary Seacole, used herbal medicines and other remedies including lead acetate and mercury chloride. She also dealt with a yellow fever outbreak in Jamaica. Her fame as a medical practitioner grew and she was soon carrying out operations on people suffering from knife and gunshot wounds.

Mary loved travelling and as a young woman visited the Bahamas, Haiti and Cuba. In these countries she collected details of how people used local plants and herbs to treat the sick. On one trip to Panama she helped treat people during another cholera epidemic. Mary carried out an autopsy on one victim and was therefore able to learn even more about the way the disease attacked the body.

In 1853 Russia invaded Turkey. Britain and France, concerned about the growing power of Russia, went to Turkey's aid. This conflict became known as the Crimean War. Soon after British soldiers arrived in Turkey, they began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases. At the time, disease was a far greater threat to soldiers than was the enemy. In the Crimean War, of the 21,000 soldiers who died, only 3,000 died from injuries received in battle.

Mary Seacole travelled to London to offer her services to the British Army. There was considerable prejudice against women's involvement in medicine and her offer was rejected. When The Times publicised the fact that a large number of British soldiers were dying of cholera there was a public outcry, and the government was forced to change its mind. Florence Nightingale, who had little practical experience of cholera, was chosen to take a team of thirty-nine nurses to treat the sick soldiers.

Mary Seacole's application to join Florence Nightingale's team was rejected. Mary, who had become a successful business woman in Jamaica, decided to travel to the Crimea at her own expense. She visited Florence Nightingale at her hospital at Scutari. Unwilling to accept defeat, Mary started up a business called the British Hotel but others referred to as “Mrs Seacole’s hut” a few miles from the battlefront. Here she sold food and drink to the British officers and a canteen for the soldiers.

Alan Palmer has argued: "Her independent status ensured a freedom of movement denied the formal nursing service; by June she was a familiar figure at the battle-front, riding forward with two mules in attendance, one carrying medicaments and the other food and wine. She brought medical comfort to the maimed and dying after the assault on the Redan, in which a quarter of the British force was killed or wounded, and she tended Italian, French, and Russian casualties at the Chernaya two months later."

Lady Alicia Blackwood wrote in A Narrative of Personal Experiences and Impressions during a Residence on the Bosphorous throughout the Crimean War (1881): "She (Mary Seacole) had, during the time of battle, and in the time of fearful distress, personally spared no pains and no exertion to visit the field of woe, and minister with her own hands such things as she could comfort, or alleviate the sufferings of those around her; freely giving to su

William H. Russell, wrote in The Times: "In the hour of their illness, these men have found a kind and successful physician, a Mrs Seacole. She is from Kingston (Jamaica) and she doctors and cures all manner of men with extraordinary success. She is always in attendance near the battlefield to aid the wounded, and has earned many a poor fellow's blessing." However, Lynn MacDonald points out: "The medical treatment she gave to soldiers is easily exaggerated - her patients were all relatively healthy walk-ins. The most serious cases went to the general hospitals, the less serious to the regimental hospitals."

Whereas Florence Nightingale and her nurses were based in a hospital several miles from the front, Mary Seacole treated her patients on the battlefield. On several occasions she was found treating wounded soldiers from both sides while the battle was still going on. However, most of her time on battle days went to selling food and drink to officers and spectators.

After the war ended in 1856 Mary Seacole returned to England where she opened a canteen at Aldershot, a venture that failed through lack of funds. By November she was bankrupt. She was encouraged to write an autobiography, published by Blackwood in July 1857 as the Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole. It sold well and lived in some comfort during her final years. Mary Seacole died of apoplexy in London on 14th May, 1881.

On 31st December 2012, Guy Walters reported in The Daily Mail: "The £500,000 memorial - larger than the statue of Florence Nightingale near Pall Mall - will show Seacole marching out to the battlefield, a medical bag over her shoulder, a row of medals proudly pinned to her chest. There's just one problem: historians around the world are growing increasingly uneasy about the statue, amid claims the adulation of Seacole has gone too far. They claim her achievements have been hugely oversold for political reasons, and out of a commendable - but in this case misguided - desire to create positive black role models. Now Seacole is at the centre of a new controversy with the news that the story of her life will no longer be taught to thousands of pupils. Westminster Education Secretary Michael Gove has decreed that instead they will learn about traditional figures such as Oliver Cromwell and Winston Churchill."

Walters quoted Lynn MacDonald, a history professor and world expert on Florence Nightingale, who feels Seacole is being promoted at the expense of Nightingale. "Nightingale was the pioneer nurse, not Mary Seacole. It's fine to have a statue to whoever you want, but Seacole was not a pioneer nurse, she didn't call herself a nurse, she didn't practise nursing, and she had no association with St Thomas's or any other hospital."

Imran Kahn, an executive member of Conservative Muslim Forum and a former Conservative councillor, argued in New Statesman on 5th January, 2013: "According to newspaper reports, Mary Seacole is to be dropped from the national curriculum so history teachers can concentrate on Winston Churchill and Oliver Cromwell. Tellingly, teachers themselves have not been coming forward to offer support for this move. The idea that schools must silence black voices so teachers can talk about Churchill, Cromwell or Nelson is one that barely merits serious argument. But bearing in mind that the abolition of slavery occurred during the lifetime of Mary Seacole in 1840, and the gigantic military presence in the British West Indies – 93 infantry regiments serving between 1793 and 1815 – not to mention her own crucial role, Seacole is ideally placed to mark out hugely significant historical events. Michael Gove must trust teachers to decide what is in the best interests of children, instead of air-brushing black people out of history. There is no question that historical black role models such as Seacole give children of all races important tools in overcoming racist assumptions about black and Asian peoples’ contribution to Britain. Knowing about black history educates all of us, promotes respect and helps to inculcate shared multicultural values."

Opponents of the idea of removing Mary Seacole from the National Curriculum started an online petition: "The Government is proposing to remove Mary Seacole from the National Curriculum. We are opposed to this and wish to see Mary Seacole retained so that current and future generations can appreciate this important historical person. Her role in the Crimea War fully justifies Mary Seacole's status as a Victorian figure taught in schools today. She was a national heroine on her return to Britain and a crowd of 80,000 attended a four day fundraising benefit in her honour in 1857. Her inclusion on the National Curriculum came as a result of a tireless campaigning to recognise someone who had become a forgotten figure in modern times. Her proposed removal can only be attributed to a recent backlash against Mary Seacole as a symbol of 'political correctness' by Right-wing media and commentators. To remove Mary Seacole from the National Curriculum is tantamount to rewriting history to fit a worldview hostile to Britain's historical diversity.... Mary Seacole the only Black figure to feature in the National Curriculum not connected to civil rights or enslavement and removing someone who was voted by the public the Greatest Black Briton sends out the wrong signals. We should be taught more Black history not less."

The petition was signed by 35,000 people and The Independent reported on 7th February, 2013: "The 'greatest black Briton' Mary Seacole is to remain on the National Curriculum after an apparent U-turn by Education Secretary Michael Gove, The Independent has learned. The move represents a major victory for campaigners, who opposed his plans to drop her. The reprieve was granted under pressure from Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, as well as Operation Black Vote which set up a petition signed by more than 35,000 people. On the old Curriculum, Mary Seacole - who cared for soldiers during the Crimean War – appeared in the annex as suggested as someone primary school teachers could use in their classrooms to illustrate Victorian Britain. In the new document, her story is even more central. Seacole, one of the first and most prominent black figures in British history, appears alongside Florence Nightingale and Annie Besant as a figure high school pupils should cover in order to learn about."

On this day in 1865 Major Henry Wirz, is executed for war crimes. On the outbreak of the American Civil War Wirz joined the Confederate Army. A sergeant in the Louisiana Volunteers, Wirz was badly wounded at the battle at Fair Oaks (May, 1862) and lost the use of his right arm. Unable to continue in active service, Wirz became a clerk at Libby Prison in Richmond. His commanding officer, Brigadier General John Henry Winder, was impressed by Wirz and he was soon promoted to the rank of major.

During the summer of 1863 an agreement under which Union and Confederate captives were exchanged, came to an end. There was now a rapid increase in the number of prisoners and so it was decided to build Andersonville Prison in Georgia. In April, 1864 Winder appointed Wirz as commandant of this new prison camp.

By August, 1864, there were 32,000 Union Army prisoners in Andersonville. The Confederate authorities did not provide enough food for the prison and men began to die of starvation. The water became polluted and disease was a constant problem. Of the 49,485 prisoners who entered the camp, nearly 13,000 died from disease and malnutrition.

When the Union Army arrived in Andersonville in May, 1865, photographs of the prisoners were taken and the following month they appeared in Harper's Weekly. The photographs caused considerable anger and calls were made for the people responsible to be punished for these crimes. It was eventually decided to charge General Robert Lee, James Seddon, the Secretary of War, and several other Confederate generals and politicians with "conspiring to injure the health and destroy the lives of United States soldiers held as prisoners by the Confederate States".

In August, 1865 President Andrew Johnson ordered that the charges against the Confederate generals and politicians should be dropped. However, he did give his approval for Wirz to be charged with "wanton cruelty". Wirz appeared before a military commission headed by Major General Lew Wallace on 21st August, 1865. During the trial a letter from Wirz was presented that showed that he had complained to his superiors about the shortage of food being provided for the prisoners. However, former inmates at Andersonville testified that Wirz inspected the prison every day and often warned that if any man escaped he would "starve every damn Yankee for it." When Wirz fell ill during the trial Wallace forced to attend and was brought into court on a stretcher.

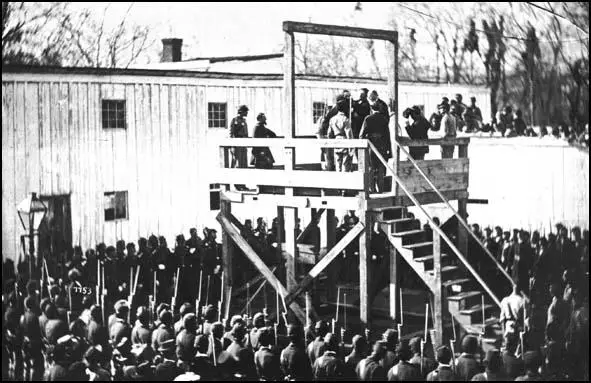

Wirz was found guilty on 6th November and sentenced to death. He was taken to Washington to be executed in the same yard where those involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had died. Alexander Gardner, the famous photographer, was invited to record the event.

The execution took place on the 10th November. The gallows were surrounded by Union Army soldiers who throughout the procedure chanted "Wirz, remember, Andersonville." Accompanied by a Catholic priest, Wirz refused to make a last minute confession, claiming he was not guilty of committing any crime.

Major Russell read the death warrant and then told Wirz he "deplored this duty."Wirz replied that: "I know what orders are, Major. And I am being hanged for obeying them." After a black hood was placed over his head, and the noose adjusted, a spring was touched and the trap door opened. However, the drop failed to break his neck and it took him two minutes to die. During this time the soldiers continued to chant: "Wirz, remember, Andersonville."

the death warrant to Henry Wirz on the gallows at Washington Penitentiary.

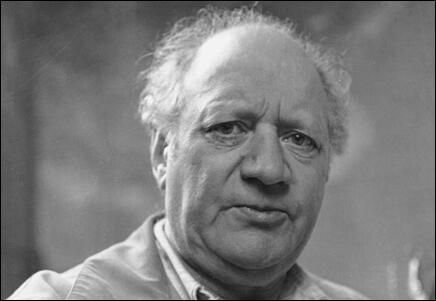

On this day in 1880 Jacob Epstein, was born. In 1914 Epstein became associated with a new movement called Vorticism. The leader of this group was Percy Wyndham Lewis. In his journal, Blast, Lewis attacked the sentimentality of 19th century art and emphasized the value of violence, energy and the machine. In the visual arts Vorticism was expressed in abstract compositions of bold lines, sharp angles and planes. Others associated with this movement included Christopher Nevinson, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, William Roberts, David Bomberg and Edward Wadsworth. It has been argued that his most experimental work, Rock Drill (1914) reflects "the embodiment of the vorticist passion for dynamism and of their virile aesthetic."

Epstein's friends campaigned for him to become a government war artist during the First World War. This idea was rejected by the authorities and in 1917 he was conscripted and became a private in the Jewish 38th battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. He was discharged in 1918 without leaving England, having suffered a mental breakdown.

The Risen Christ, produced as a result of his experiences in the war caused problems when it was exhibited in 1920. Epstein considered the figure to be an anti-war statement and declared that he would ideally like it to be remodelled and made hundreds of feet high as a "mighty symbolic warning to all lands." John Galsworthy remarked after visiting the exhibition that: "I can never forgive Mr. Epstein for his representation of Our Lord."

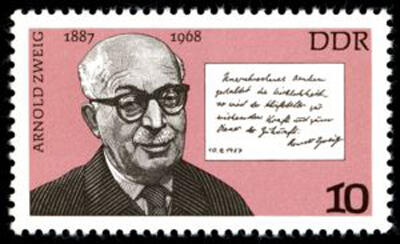

On this day in 1886 Arnold Zweig was born in Germany. On the outbreak of the First World War Zweig joined the German Army and served at Verdun and at the German Army Headquarters on the Eastern Front. Influenced by Under Fire by Henri Barbusse, Zweig wrote the novel, The Case of Sergeant Grisha (1928). Based on an actual case, the story concerns a Russian sergeant who is caught, tried and executed as a German deserter.

An opponent of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, Zweig was co-editor of the anti-fascist magazine, World Stage . Exiled by the Nazis in 1934, he continued to publish novels including Education Before Verdun (1935), The Crowning of a King (1937) and The Axe of Wandsbek (1947).

Zweig returned to Germany after the Second World War and served as president of the German Academy of the Arts (1950-53) and won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1959. Arnold Zweig died in East Berlin on 26th November 1968.

On this day in 1907 the Women's Freedom League is formed. That year some leading members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Clare Mordan and Mary Blathwayt were having too much influence over the organisation.

In a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference. As Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence pointed out: "She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people. Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to democracy, and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own."

Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst sent out a letter to all branches of the WSPU stating that this was not in any way a democratic group. "We are not playing experiments with representative government. We are not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are a militant movement... It is not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are militant movement... It is after all a voluntary militant movement: those who cannot follow the general must drop out of the ranks." As Simon Webb has pointed out: "This is quite unambiguous. Members must not expect to influence policy or question the leader, the role is limited to obeying orders."

As a result of this speech, Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Emma Sproson, Margaret Nevinson, Henria Williams, Violet Tillard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Most of its members were socialists who wanted to work closely with the Labour Party who "regarded it as hypocritical for a movement for women's democracy to deny democracy to its own members." Christabel Pankhurst attempted to play down the conflict. She stated, "please don't call it a split there has been no particular row... it is more of a parting of company."

Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig and Edith How-Martyn were all members of the Independent Labour Party. However, they distrusted the other political parties who had for so long blocked attempts to extend the franchise to women. Therefore they wanted "a women's suffrage organisation independent of the political parties; an organisation run and controlled by women which would prioritise women's suffrage above all else; a campaign which would be intense and militant, and which would not end until women had achieved their demands - equal suffrage on the same terms as men."

Violet Tillard became Assistant Organising Secretary of the organisation. She was active in promoting women's suffrage in newspapers. In one letter she pointed out the difference between the Women's Freedom League and the Women Social & Political Union. "The Women's Freedom League differs from the Women's Social and Political Union chiefly in the internal organisation, which in democratic; and in the fact that it is not part of its policy at present to interrupt Cabinet Ministers at meetings; but the societies at one in their aim the removal of the sex disability, and in their policy of opposing the Government at bye-elections."

The Women's Freedom League "had formed at least sixty branches by 1909, with a constant membership in these of no more than 5,000 women, although given the tendency for League branches to disband and reform, and for new branches to emerge, the number of women who at one stage were members of the League was much greater." In a letter to The Times the WFL Hon. Secretary, Edith How-Martyn wrote that they had sixty-five local branches, with a total membership of "about 5,000... it must be remembered that we have a large body of sympathizers who will not become members because they cannot fulfil the very stringent regulations."

Teresa Billington-Greig became chairman of the WFL Executive Committee and National Honorary Organising Secretary. "I presided at both the conferences of the WFL which decided its future and at those that followed annually until 1911. This was by the express wish of Mrs Despard, who felt that the conduct of big business meetings was not the job for her... The queen-pin of our movement was of course Edith How-Martyn, who, as Honorary Secretary, carried the heaviest burden with a spirit which never faltered and won admiration from us all."

Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. Court protests against the trial of women "by man made laws", a favourite idea of Teresa Billington-Greig, were carried out by the WFL.

On 28th October 1908 Muriel Matters organised a WFL demonstration in the House of Commons. Two women chained themselves to the grille in front of the Ladies' Gallery. Meanwhile a group of women demonstrated in St Stephen's Hall. Fourteen of the women were arrested and taken to Cannon Row Police Station. (12) As a result of this several women spent a month in prison.

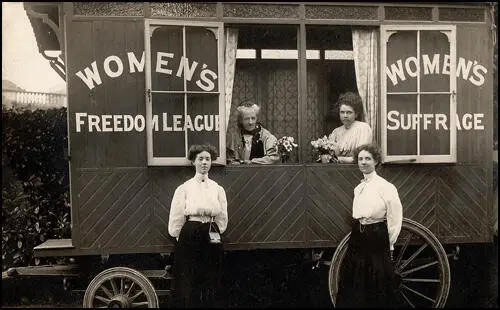

Violet Tillard Assistant Organising Secretary of the WFL helped establish branches of the League on a caravan tour of the south-east counties of England. Tillard also established WFL branches in Ipswich, Carmarthen and Cardiff. In November, 1908, the caravan visited visited Sussex. On 28th November, Tillard spoke at a meeting at Upminster addressed by Alice Schofield and Henria Williams. (14)

Muriel Matters had arrived from Australia in 1905. She lived in a colony had gained attention for being the first self-governing territory to give women equal franchise on the same terms as it was granted to men. She was one of the more creative members of the Women's Freedom League. In February 1909, Muriel Matters gained further notoriety when she travelled across London in a hot air balloon, dropping suffrage literature on the unsuspecting population!

The Women's Freedom League established its own newspaper, The Vote. The first edition was published on 30th October 1909. It claimed: "We hope and believe that through its pages the public will come to understand what the Parliamentary Franchise means to us women. Now it will be both a symbol of citizenship and the key to a door opening out on such service to the community as we have never yet been allowed to render, and therefore it is our earnest hope that our paper will keep its place in the hearts of men and women long after the first victory has been won."

Two of the Women's Freedom League leaders, Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Despard, were both talented writers and were the main people responsible for producing the newspaper. One of Britain's leading writers, Cicely Hamilton, became editor of the newspaper.

The Vote never rivalled either The Common Cause or Votes for Women, but members of the WFL did recognise the importance of their own paper in keeping members informed and in generating a sense of a united organisation. It also used it to explain the philosophy of the group: "We must rebel, we must not rest until the ballot box is no longer the symbol of sex tyranny but the symbol of political sex equality."

As Edith How-Martyn explained: "We cannot reiterate too often that our object is to give a practical example of the impasse which would be produced in our national life if women seriously began to refuse their consent to the autocratic government by men. Passive resistance against unjust authority is binding on those who believe in doing something to win their freedom. Until women win representation they are morally justified in demonstrating that their exclusion from citizenship certainly does involve national injury."

Violet Tillard standing in front of the Women's Freedom League caravan.

On this day in 1936 Wyndham Robinson published a cartoon expressing a fear of communism. Wyndham Robinson, the son of a journalist, was born in London in 1883. He studied at the Lambeth Art School and the Chelsea School of Art. He intended to become a fashion artist but after seeing the work of Will Dyson he decided to become a cartoonist.

On the outbreak of the First World War he joined the Artists Rifles. The regiment largely consisted of painters, sculptors, engravers, musicians, architects and actors. Some of the artists who joined the regiment in 1914 included Edgell Rickword, Charles Jagger, Wilfred Owen, Bert Thomas, R. C. Sherriff, Edward Thomas, Paul Nash, John Nash, John Lavery, Alfred Leete, Frank Dobson, Eric Blore and Eugene Bennett.

Robinson was transferred to the Royal Field Artillery and served on the Western Front, attaining the rank of captain. After the Armistice Robinson spent a year in Germany with the Army of Occupation. He then moved to Southern Rhodesia where he became a tobacco-farmer. In 1928 he returned to cartooning and worked for The Cape Times.

In 1932 Robinson was appointed as the political cartoonist for The Morning Post. During the Great Depression he became a strong critic of the government of Ramsay MacDonald. In one cartoon published on 31st July 1933, Robinson's compared MacDonald's inactivity with that of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. He also portrayed Stanley Baldwin as disinterested in the subject.

According to Martin Walker, the author of Daily Sketches: A Cartoon History of Twentieth Century Britain (1978): "Wyndham Robinson, one of the most talented cartoonists to emerge in the 1930s... made the valid point that such Depression-beating energy could be mobilised quite as effectively by that other great democracy, the US, under Roosevelt and the New Deal. By comparison, MacDonald is an old woman."

Wyndham Robinson believed that there was a strong danger that the unemployed would be attracted to the policies of the Communist Party of Great Britain. This was reflected in the cartoon, The End of the Trail, published in The Morning Post on 10th November, 1936. The following year he joined the The Daily Telegraph. He also had his work published in Punch Magazine, London Opinion and The Tatler.

On this day in 1939 Charlotte Despard died after a fall in her new house near Belfast.

Charlotte French, the daughter of William French, a naval commander from Ireland, was born in Ripple, Kent, in 1844. By the age of ten her father had died and her mother was committed to an insane asylum and she was sent to London to live with relatives.

She had a conventional education. Later she was to recall: "I asked my governess why God had made slaves, and I was promptly sent to bed. Oh, how I hated the nurses and governesses, and I stood at the gates of my home and envied the little village children. They were free. They had liberty… The village children could run about as they liked and did not seem to be troubled by those superior persons, nurses and governesses. I went to the nearest railway station and tried to buy a ticket. Needless to say, I was stopped, but I had gone so far that I could not return that night, and I spent it alone at a station inn. After that, lest I should infect my sisters with my spirit of insubordination, I was kept in solitary confinement for three or four days, and then sent away to school."

For several years she toured the continent with her unmarried sisters. Charlotte met Maximilian Carden Despard, an Anglo-Irish businessman who had made a fortune in the Far East. The couple married on 20th December 1870. With her husband's encouragement, she published her first novel, Chaste as Ice, Pure as Snow in 1874. During the next sixteen years Charlotte wrote ten novels. Most of these novels were romantic love stories but A Voice from the Dim Millions dealt with the problems of a poor young factory worker. Charlotte was unable to find a publisher for this novel.

When her husband died in 1890, Charlotte decided to dedicate the rest of her life to helping the poor. She left her luxurious house in Esher and moved to Wandsworth to live with the people she intended to assist. According to her biographer, Margaret Mulvihill: "There she funded and staffed a health clinic, as well as organizing youth and working men's clubs, and a soup kitchen for the local unemployed. During the week she lived above one of her welfare shops and her identification with the local community was sealed by her conversion to Catholicism. At the end of 1894 she was elected as a guardian for the Vauxhall board of the Lambeth poor-law union. She proved herself a brilliant committee woman, bringing a rare combination of informed compassion, practical experience, and military efficiency to the board's deliberations."

In 1894 Charlotte Despard was elected as a Poor Law Guardian in Lambeth. Charlotte became friends with George Lansbury and for the next few years became involved in the campaign to reform the Poor Law system. Charlotte Despard joined the Social Democratic Federation and later the Independent Labour Party. Despard also got to know Margaret Bondfield, the trade union leader and Keir Hardie, the new leader of the Labour Party.

Despard became a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). However, in 1906, frustrated by the NUWSS lack of success, she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), an organisation established by Emmeline Pankhurst and her three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic pointed out, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.”

Charlotte Despard later recalled: "I had sought and found comradeship of some sort with men. I had marched with great processions of the unemployed. I had stood on the platforms of Labour men and Socialists. I had tried to stir up the people to a sense of shame about the misery of their homes, and the degradation of their women and children. I had listened with sympathy to fiery denunciations of Governments and the Capitalist systems to which they belong. Amongst all these experiences, I had not found what I met on the threshold of this young, vigorous Union of Hearts."

On 23rd October, 1906, Charlotte Despard was arrested with Mary Gawthorpe during a protest meeting at the House of Commons. As Sylvia Pankhurst later explained: "Mary Gawthorpe mounted one of the settees close to the statue of Sir Stafford Northcote and began to address the crowd of visitors who were waiting to interview various Members of Parliament. The other women closed up around her, but in the twinkling of an eye dozens of policemen sprang forward, tore the tiny creature from her post and swiftly rushed her out of the Lobby. Instantly Mrs. Despard stepped into the breach; but she also was roughly dragged away."

In 1907 she was imprisoned twice in Holloway Prison. However, like other leading members of the WSPU she began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy womenwere having too much influence over the organisation.

In a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference. As Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence pointed out: "She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people. Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to democracy, and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own."

As a result of this speech, Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL were especially critical of the WSPU arson campaign.

In a speech in 1910 Despard argued: "Fundamentally all social and political questions are economic. With equal wages, the male worker would no longer fear that his female colleague might put him out of a job, and 'men and women will unite to effect a complete transformation to the industrial environment… A woman needs economic independence to live as an equal with her husband. It is indeed deplorable that the work of the wife and mother is not rewarded. I hope that the time will come when it is illegal for this strenuous form of industry to be unremunerated."

Despard spent a great deal of time in Ireland and in 1908 she joined with Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Margaret Cousins to form the Irish Women's Franchise League. In 1909 Despard met Gandhi and was influenced by his theory of "passive resistance". As the leading figure of the WFL. Despard urged members not to pay taxes and to boycott the 1911 Census. Despard financially supported the locked-out workers during the labour dispute in Dublin and also helped establish the Irish Workers' College in the city.

The Women's Freedom League grew rapidly, and soon had sixty branches throughout Britain with an overall membership of about 4,000 people. The WFL also established its own newspaper, The Vote. Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Despard were both talented writers and were the main people responsible for producing the newspaper. It was used to inform the public of WFL campaigns such as the refusal to pay taxes and to fill in the 1911 Census forms. Another contributor was one of Britain's leading writers, Cicely Hamilton.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Despard, like most members of the Women's Freedom League, was a pacifist, and so during the First World War she refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. Ironically, her brother, General John French, was Chief of Staff of the British Army and commander of the British Expeditionary Force sent to Europe in August 1914. Her sister, Catherine Harley, was also a supporter of the war and served in the Scottish Women's Hospital in France.

Charlotte Despard argued that the British government was not doing enough to bring an end to the war and supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Council for a negotiated peace. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Charlotte Despard became the Labour Party candidate in Battersea in the post-war election. However, in the euphoria of Britain's victory, Despard's anti-war views were very unpopular and like all the other pacifist candidates, who stood in the election, she was defeated.

Despard's biographer, Margaret Mulvihill, has argued: "Among the suffragette leaders she had stood out as a supporter of Irish home rule, and when that movement gave way to the struggle for complete independence she became an active supporter of the British solidarity organization the Irish Self Determination League. Her sympathy for the Irish republican movement brought her into direct conflict with her brother, who in 1918 had been sworn in as lord lieutenant of Ireland. While he set about crushing the rebels, his sister was supporting them."

In 1920 Despard toured Ireland as a member of the Labour Party Commission of Inquiry. Together with Maud Gonne, she collected first-hand evidence of army and police atrocities in Cork and Kerry. The two women also formed the Women's Prisoners' Defence League to support republican prisoners. In the 1920s Despard became involved in the Sinn Fein campaign for a united Ireland.

In 1930 Despard and Hanna Sheehy Skeffington made a tour of the Soviet Union. Impressed with what she saw she joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and became secretary of the Friends of Soviet Russia organization.