On this day on 9th February

On this day in 1554 Lady Jane Grey was executed. Jane Grey, the eldest surviving child of Henry Grey, the Marquess of Dorset, was born in October 1537. Her mother, Frances, was the daughter of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Mary Tudor, younger sister of Henry VIII. Jane was therefore a cousin of Edward VI. Jane was therefore fourth in line to the throne, supposing none of the King's children left any heirs.

Elizabeth Jenkins has pointed out that the marriage had produced three children, Jane, Catherine and Mary. "The two younger were unremarkable, except that the youngest had the unfortunate distinction of being a dwarf. All the moral and intellectual endowments and all the graces of the family were concentrated in the eldest daughter. Like her cousins, she had been very carefully taught." A young Cambridge scholar, John Aylmer, was appointed as the family tutor when Jane was four years old. "He had carried her in his arms and taught her to pronounce words. He had given her a thorough education in Greek and Latin, but his chief concern was with her spiritual development, over which he watched with anxious devotion."

Aylmer reported that Jane showed exceptional academic ability and was sent to join the household of the widowed Queen Catherine Parr in the spring of 1547 she was able to "benefit from the educational opportunities then available in court circles for girls as well as boys... she was also encouraged to absorb the teachings of the evangelical protestantism of which Catherine was a leading devotee."

Jane complained to one of her teachers, Roger Ascham, about the way she was treated by her parents: "For when I am in presence either of father or mother, whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand or go, eat, drink, be merry or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing anything else, I must do it, as it were… even so perfectly as God made the world, or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea presently some times with pinches, nips and bobs… that I think myself in hell."

Jane was friendly with Mary despite their growing religious divergence. She tended to share the same views as Elizabeth on the religious reforms taking place. Presented with a rich gown of tinsel cloth of gold on velvet by Mary, she refused to wear it, saying that "it were a shame to follow my Lady Mary against God's word and leave my Lady Elizabeth which followeth God's word". (5) According to Alison Plowden " Elizabeth at this time affected a severely plain style of dress, setting the fashion for other high-born protestant maidens."

In April 1552 Edward VI fell ill with a disease that was diagnosed first as smallpox and later as measles. He made a surprising recovery and wrote to his sister, Elizabeth, that he had never felt better. However, in December he developed a cough. Elizabeth asked to see her brother but John Dudley, the lord protector, said it was too dangerous. In February 1553, his doctors believed he was suffering from tuberculosis. In March the Venetian envoy saw him and said that although still quite handsome, Edward was clearly dying.

In order to secure his hold on power, Dudley devised a plan where Jane would marry his son, Guildford Dudley. According to Philippa Jones, the author Elizabeth: Virgin Queen (2010): "Early in 1553, Dudley... began working to persuade the King to change the succession. Edward VI was reminded that Mary and Elizabeth were both illegitimate, and more importantly, that Mary would bring Catholicism back to England. Dudley reasoned that if Mary were to be struck out of the succession, how could Elizabeth, her equal, be left in? Furthermore, he argued that both the princesses would seek foreign husbands, jeopardizing English sovereignty."

Under the influence of the Lord Protector, Edward made plans for the succession. Sir Edward Montague, chief justice of the common pleas, testified that "the king by his own mouth said" that he was prepared to alter the succession because the marriage of either Princess Mary or Princess Elizabeth to a foreigner might undermine both "the laws of this realm" and "his proceedings in religion". According to Montague, Edward also thought his sisters bore the "shame" of illegitimacy.

At first Jane refused to marry Guildford on the grounds that she had already been promised to Edward Seymour, the Earl of Hertford, the son of Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset. However, her protests were overcome "by the urgency of her mother and the violence of her father, who compelled her to accede to his commands by blows". The marriage took place on 21st May 1553 at Durham House, the Dudleys' London residence, and afterwards Jane went back to her parents. She was told Edward was dying and she must hold herself in readiness for a summons at any moment. "According to her own account, Jane did not take this seriously. Nevertheless she was obliged to return to Durham House. After a few days she fell sick and, convinced that she was being poisoned, begged leave to go out to the royal manor at Chelsea to recuperate."

King Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. Three days later one of Northumberland's daughters came to take her to Syon House, where she was ceremoniously informed that the king had indeed nominated her to succeed him. Jane was apparently "stupefied and troubled" by the news, falling to the ground weeping and declaring her "insufficiency", but at the same time praying that if what was given to her was "‘rightfully and lawfully hers", God would grant her grace to govern the realm to his glory and service.

On 10th July, Queen Jane arrived in London. An Italian spectator, witnessing her arrival, commented: "She is very short and thin, but prettily shaped and graceful. She has small features and a well-made nose, the mouth flexible and the lips red. The eyebrows are arched and darker than her hair, which is nearly red. Her eyes are sparkling and reddish brown in colour." Guildford Dudley, "a tall strong boy with light hair’, walked beside her, but Jane apparently refused to make him king, saying that "the crown was not a plaything for boys and girls."

Jane was proclaimed queen at the Cross in Cheapside, a letter announcing her accession was circulated to the lords lieutenant of the counties, and Bishop Nicolas Ridley of London preached a sermon in her favour at Paul's Cross, denouncing both Mary and Elizabeth as bastards, but Mary especially as a papist who would bring foreigners into the country. It was only at this point that Jane realised that she was "deceived by the Duke of Northumberland and the council and ill-treated by my husband and his mother".

Mary, who had been warned of what Dudley had done and instead of going to London as requested by Dudley, she fled to Kenninghall in Norfolk. As Ann Weikel has pointed out: "Both the earl of Bath and Huddleston joined Mary while others rallied the conservative gentry of Norfolk and Suffolk. Men like Sir Henry Bedingfield arrived with troops or money as soon as they heard the news, and as she moved to the more secure fortress at Framlingham, Suffolk, local magnates like Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who had hesitated at first, also joined her forces."

Mary summoned the nobility and gentry to support her claim to the throne. Richard Rex argues that this development had consequences for her sister, Elizabeth: "Once it was clear which way the wind was blowing, she (Elizabeth) gave every indication of endorsing her sister's claim to the throne. Self-interest dictated her policy, for Mary's claim rested on the same basis as her own, the Act of Succession of 1544. It is unlikely that Elizabeth could have outmanoeuvred Northumberland if Mary had failed to overcome him. It was her good fortune that Mary, in vindicating her own claim to the throne, also safeguarded Elizabeth's."

The problem for Dudley was that the vast majority of the English people still saw themselves as "Catholic in religious feeling; and a very great majority were certainly unwilling to see - King Henry's eldest daughter lose her birthright." When most of Dudley's troops deserted he surrendered at Cambridge on 23rd July, along with his sons and a few friends, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London two days later. Tried for high treason on 18th August he claimed to have done nothing save by the king's command and the privy council's consent. Mary had him executed at Tower Hill on 22nd August. In his final speech he warned the crowd to remain loyal to the Catholic Church.

Queen Mary told a foreign ambassador that her conscience would not allow her to have Jane put to death. Jane was given comfortable quarters in the house of a gentleman gaoler. The anonymous author of the Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary (c. 1554), dropped in for dinner, finding the Lady Jane sitting in the place of honour. She made the visitor welcome and asked for news of the outside world, before going on to speak gratefully of Mary - "I beseech God she may long continue" and made a fierce attack against John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland: "Woe worth him! He hath brought me and our stock in most miserable calamity by his exceeding ambition".

Jane, together with Guildford Dudley and two more of his brothers, stood trial for treason on 19th November. They were all found guilty but foreign ambassadors in London reported that Jane's life would be spared. Mary's attitude towards Jane changed when her father, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, joined the rebellion led by Sir Thomas Wyatt against her proposed marriage to Philip of Spain. Although there is any evidence that Jane had any foreknowledge of the conspiracy, "her very existence as a possible figurehead for protestant discontent made her an unacceptable danger to the state". Mary, now agreed with her advisers and the date of Jane's execution was fixed for 9th February, 1554. However, she was still willing to forgive Jane and sent John Feckenham, the new dean of St Paul's, over to the Tower of London in an attempt to see if he could convert this "obdurate heretic". However, she refused to change her Protestant beliefs.

Jane watched the execution of her husband from the window of her room in the Tower of London. She then came out leaning on the arm of Sir John Brydges, Lieutenant of the Tower. "Lady Jane was calm, although. Elizabeth and Ellen (her two women attendants) wept... The executioner kneeled down and asked for forgiveness, which she gave most willingly... she said: "I pray you dispatch me quickly."

Lady Jane Grey then made a brief speech: "Good people, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same. The fact, indeed, against the queen's highness was unlawful, and the consenting thereunto by me: but touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocency, before God, and the face of you, good Christian people, this day' and therewith she wrung her hands, in which she had her book."Kneeling, she repeated the 51st Psalm in English.

According to the Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary: "Then she kneeled down, saying, 'Will you take it off before I lay me down?' and the hangman answered her, 'No, madame.' She tied the kercher about her eyes; then feeling for the block said, 'What shall I do? Where is it?' One of the standers-by guiding her thereto, she laid her head down upon the block, and stretched forth her body and said: 'Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit!' And so she ended."

Stories circulated as to the piety and dignity on the scaffold, however, she did not receive a great deal of sympathy. As Alison Plowden has pointed out: "The judicial murder of sixteen-year-old Jane Grey, and no one ever pretended it was anything else, caused no great stir at the time, not even among the militantly protestant Londoners. Jane had never been a well-known figure, and in any case was too closely associated with the unpopular Dudleys and their failed coup to command much public sympathy."

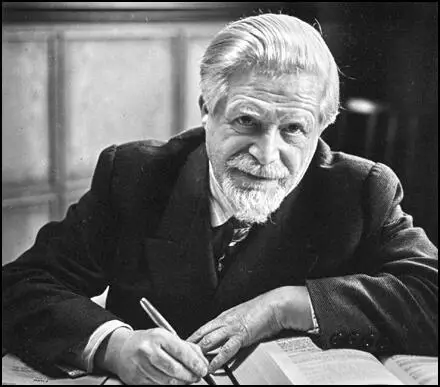

On this day in 1763 parliamentary reformer, Joseph Gerrald, the son of a wealthy planter in the West Indies, was born in St. Christopher on 9th February 1763. At the age of two Joseph and his mother, Ann Gerrald, came to England. Anne Gerrald died soon after arriving and Joseph was sent to a boarding school in Hammersmith. Later he was transferred to the care of Dr. Samuel Parr at Stanmore School. After finishing his education Gerrald returned to the plantation in the West Indies that he had inherited on the death of his father.

By the time Gerrald arrived in the West Indies the plantation was in financial difficulty. Gerrald married but his wife died after giving birth to her second child. Gerrald took his two young children to America where he practised law in Pennsylvania. It was while in America that he met Tom Paine. Gerrald was deeply influenced by Paine's political ideas and when he moved to England in 1788 he became involved in the campaign for parliamentary reform. In 1792 Gerrald joined the London Corresponding Society and the following year wrote the pamphlet A Convention is the Only Means of Saving Us from Ruin.

At an open-air meeting held at Chalk Farm on 24th October, the London Corresponding Society elected Gerrald and Maurice Margarot as its delegates to the Edinburgh Convention planned for November. Before they left London, Margarot and Gerrald heard the news that two of the leaders of the Scottish Reformers, Thomas Fyshe Palmer and Thomas Muir, had been arrested and charged with sedition.

In November 1792, Gerrald and Maurice Margarot arrived in Edinburgh as delegates to the British Convention of the Friends of the People. Government spies also attended these meetings in Edinburgh and on 2nd December 1793, Gerrald, Margarot and William Skirving, secretary of the Society of the Friends of the People, were arrested and charged with sedition.

Joseph Gerrald managed to obtain bail and returned to London. While waiting for his trial to take place, Gerrald heard that Margarot and Skirving had been found guilty of sedition and had been sentenced to 14 years transportation. Gerrald suffered from poor health and his friends were convinced that he would never survive being transported to Australia. Gerrald's friends pleaded with him to flee the country. Gerrald refused, arguing "my honour is pledged; and no opportunity for flight shall induce me to violate that pledge." , William Godwin, wrote a letter to Gerrald praising his decision: "Your trial, if you so please, may be a day such as England, and I believe the world, never saw. It may be the means of converting thousands, and, progressively, millions, to the cause of reason and public justice."

The trial of Joseph Gerrald began on 10th March 1794. He defiantly wore his hair loose and unpowdered in the French style. He made no real attempt to defend himself against the charges and instead concentrated on using the court to express his views on parliamentary reform. Gerrald upset the judge, Lord Braxfield, when he argued that Jesus Christ was a radical reformer. Gerrald ended his speech with the words: "What ever may become of me, my principles will last for ever. Whether I shall be permitted to glide gently down the current of life, in the bosom of my native country, among those kindred spirits whose approbation constitutes the greatest comfort of my living; whether I be doomed to drag out the remainder of my existence amidst thieves and murders, my mind, equal to either fortune, is prepared to meet the destiny that awaits it." Lord Braxfield's response was to sentence Gerrald to fourteen years transportation.

While waiting to be transported to Australia, a government minister, Henry Dundas, offered to arrange for Gerrald to be given his freedom if he promised to stop advocating parliamentary reform. Gerrald refused and on 25th May he left Portsmouth aboard the Sovereign.

Joseph Gerrald was seriously ill when he arrived in Australia on 5th November, 1795. John Fyshe Palmer looked after him for several months. Later Palmer claimed that he: "attended him night and day, and the attention of my friends who live with me was equal to mine. Some few hours before his death, he called me to his bedside, 'I die', said he, 'in the best of causes and, as you witness, without repining'." Joseph Gerrald died of tuberculosis on 16th March, 1796.

In 1845 Thomas Hume, the Radical MP, organised the building of a 90 feet high monument in Waterloo Place, Edinburgh. It contained the following inscription: "To the memory of Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald. Erected by the Friends of Parliamentary Reform in England and Scotland." On the other side of the obelisk, based on the model of Cleopatra's Needle in London, is a quotation from a speech made by Muir on 30th August, 1793: "I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause - it shall ultimately prevail - it shall finally triumph."

On this day in 1854 Aletta Jacobs, the eighth of twelve children, was born in the Netherlands. Her father was a doctor and she decided at an early age she wanted to be a member of the same profession. At this time boys and girls received different forms of secondary education. Whereas girls studied languages, art, music and handicrafts to prepare them for life as a wife and mother, a boy's education included mathematics, history, Greek, and Latin. Aletta's father managed to persuade the local boys' high school to allow his daughter to attend these classes.

After leaving high school, Jacobs went to live with one of her brothers who worked as a pharmacist. He taught her the trade and she eventually passed the relevant pharmacist exam. In 1872 she received special permission from the government to enter the University of Gröningen.

Jacobs passed her university exams in Mathematics and Physics and in 1876 entered the medical school in Amsterdam. Jacobs later wrote that during her studies she "encountered professors who openly opposed the idea of women doctors". However, she also received the strong support from other teachers and she successfully obtained her medical degree on April 2, 1878.

During the summer of 1878 Jacobs visited London where she met other feminists. This included Elizabeth Garrett Anderson who had qualified as a doctor in 1865. On her return to the Netherlands she became involved in several campaigns to improve the conditions of working class women.

Aletta Jacobs also became involved in providing women with birth-control. In her autobiography Jacobs wrote: "For social, moral, and medical reasons, women from different social classes had often asked me for some form of contraception. I had always had to fend off these requests without providing adequate explanation or advice. Eventually I sent letters to a number of women whose need was greatest. I told them that I believed I had found a means to help them, but before I could fully recommend it, they would have to agree to regular examinations during the first months of its use. Some of these women eventually agreed to the experiment, and the results were such that, some months later, I was able to announce that I could provide a safe and effective contraceptive."

Despite opposition from religious and political leaders, Jacobs started a national campaign to make contraception widely available in the Netherlands. Her birth-control clinic in Amsterdam open over 30 years before those in the United States and Britain. Her success inspired the activities of other birth-control advocates and Margaret Sanger and Marie Stopes both traveled to the Netherlands to find out more about the work of Jacobs.

Jacobs was also inspired by the work of feminists in other countries. For example, she took a keen interest in the activities of Josephine Butler who had campaigned against the Contagious Diseases Act in Britain. These acts had been introduced in the 1860s in an attempt to reduce venereal disease in the armed forces. Butler objected in principal to laws that only applied to women. Under the terms of these acts, the police could arrest women they believed were prostitutes and could then insist that they had a medical examination. Butler had considerable sympathy for the plight of prostitutes who she believed had been forced into this work by low earnings and unemployment. Jacobs shared Butler's concerned and campaigned against organized prostitution (white slave traffic).

In 1883 Jacobs attempted unsuccessfully to register to vote. This was the beginning of her campaign for universal suffrage. This generated a great deal of support after the Dutch Parliament, added the word "male" to the list of voting qualifications in 1887.

In 1893 Jacobs helped establish the Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (Woman Suffrage Alliance). Jacobs became head of the Amsterdam section and in 1903 she was elected president of the organization. Jacobs worked closely with other organizations such as the National Woman Suffrage Association and the National Union of Suffrage Societies and in 1904 was a founder member of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA). This included feminists from the United States, Britain, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Australia, and Germany.

Jacobs became one of the most important international figures in the fight for universal suffrage. In 1911 she joined Carrie Chapman Catt in a world fact-finding tour. This included visits to South Africa, Syria, Egypt, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India, Burma, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, China, and Japan.

On the outbreak of the First World War a group of women pacifists in the United States began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Jane Addams was elected president and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Mary Heaton Vorse, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Emily Bach, and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Jacobs invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Jane Addams was asked to chair the meeting and Mary Heaton Vorse, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Julia Lathrop, Leonora O'Reilly, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Emily Bach went as delegates from the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary). Afterwards, Jacobs, Addams, Macmillan, Schwimmer and Balch went to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome, Berne and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe.

Throughout this period Jacobs continued to campaign for universal suffrage. The vote was granted to women in Finland (1906), Norway (1907), Denmark (1915), Russia (1917), Germany (1918), Britain (1918), Poland (1918), Austria (1918), Czechoslovakia (1918) and Hungary (1918). Like the women of Luxemburg, Belgium and Sweden, the Netherlands had to wait until 1919 before obtaining the vote.

Aletta Jacobs died in 1929.

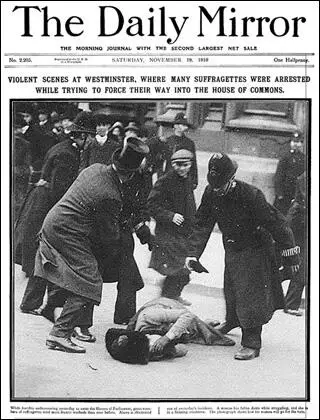

On this day in 1861 the birth of Ada Wright one of the women badly beaten badly by the police at the WSPU demonstration on 18 November, 1910. The photograph of Ada Wright on the front page of The Daily Mirror the next day caused a great deal of embarrassment to the Home Office and the government demanded that the negative be destroyed. Wright told a reporter that she had been at seven suffragette demonstrations, but had "never known the police so violent." Charles Mansell-Moullin, who had helped treat the wounded claimed that the police had used "organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputations like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police."

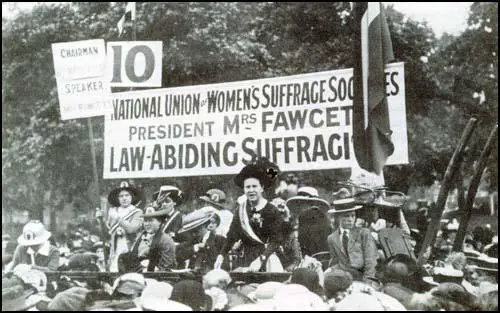

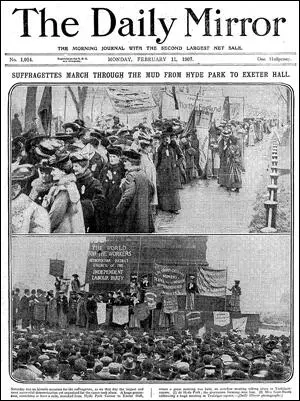

On this day in 1907 the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies organise the United Procession of Women (Mud March) in which more than 3,000 women marched from Hyde Park Corner to the Strand in support of women's suffrage.

On this day in 1882 Beatrice Potter writes in her diary about Charles Booth. "It is difficult to discover the presence of any vice or even weakness in him. Conscience, reason, and dutiful affect in, are his great qualities; what other characteristics he has are not to be observed by the ordinary friend. But he interests me as a man who has his nature completely under his control, and who has risen out of it, uncynical, vigorous and energetic in mind without egotism."

Charles Booth, the son of a wealthy businessman, was born in Liverpool on 30th March, 1840. Booth's father was a Unitarian and head of the Lamport & Holt Steamship Company. When Booth was twenty-two his father died and took over the running of the company. Booth was an energetic leader and soon added a successful glove manufacturing concern to his expanding shipping interests.

In the 1860s Booth became interested in the philosophy of Auguste Comte, the founder of modern sociology. Booth was especially attracted to Comte's idea that in the future, the scientific industrialist would take over the social leadership from church ministers. One of the consequences of reading Comte was that Booth began to lose his religious faith.

In 1885 Charles Booth became angry about the claim made by H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation, that 25% of the population of London lived in abject poverty. Bored with running his successful business, Booth decided to investigate the incidence of pauperism in the East End of the city. He recruited a team of researchers that included his cousin, Beatrice Potter.

The result of Booth's investigations, Labour and Life of the People, was published in 1889. Booth's book revealled that the situation was even worse than that suggested by H. H. Hyndman. Booth research suggested that 35% rather than 25% were living in abject poverty. Booth now decided to expand his research to cover the rest of London. He continued to run his business during the day and confined his writing to evenings and weekends. In an effort to obtain a comprehensive and reliable survey Booth and his small team of researchers made at least two visits to every street in the city.

Beatrice Potter later recalled: "It is difficult to discover the presence of any vice or even weakness in him. Conscience, reason, and dutiful affect in, are his great qualities; what other characteristics he has are not to be observed by the ordinary friend. But he interests me as a man who has his nature completely under his control, and who has risen out of it, uncynical, vigorous and energetic in mind without egotism."

Over a twelve year period (1891 to 1903) Booth published 17 volumes of Life and Labour of the People of London. In these books Booth argued that the stare should assume responsibility for those living in poverty. One of the proposals he made was for the introduction of Old Age Pensions. A measure that he described as "limited socialism". Booth believed that if the government failed to take action, Britain was in danger of experiencing a socialist revolution.

Whereas many of his researchers, including Beatrice Potter, became socialists as a result of what they discovered while investigating poverty, Booth became more conservative in his views. Strongly opposed to trade unions, he was unhappy with the sympathetic treatment they had received from the the Liberal government that took power after the 1906 General Election. Booth now renounced his early support for the Liberal Party and joined the Conservative Party.

Charles Booth died on 23rd November, 1916.

On this day in 1893 Elsie Duval, daughter of Ernest Duval, was born. Her mother, Emily Duval, was a member of the Women Social & Political Union before joining the Women's Freedom League in 1907.

In January 1908 Elsie Duval was sentenced to one month's imprisonment after taking part in a demonstration at the home of Herbert Asquith. In 1911 Emily Duval left the WFL because it was not militant enough and rejoined the WSPU. Elsie's father, was also a supporter of women's suffrage and was a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. Her brother, Victor Duval, was also imprisoned several times for taking part in demonstrations.

Elsie Duval joined the WSPU at the age of fifteen. She was at first too young to be involved in militant activity and was not arrested until 23rd November 1911 on a charge of obstructing the police. In March 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Elsie took part in this campaign and in July was sentenced to a month's imprisonment for breaking a window in Clapham. While in prison she was forcibly fed nine times.

Duval also took part in the WSPU's arson campaign. It is believed she was responsible for burning Sanderstead Station. She was arrested for "loitering with intent" on 3rd April 1913. She was sentenced to one month's imprisonment. After being released under the Cat and Mouse Act, she escaped with her boyfriend, Hugh Franklin, to Belgium and stayed in Brussels. She received a letter from Jessie Kenney that said: "Miss Pankhurst thinks it would be better for you to stay where you are for the time being and until you get stronger."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Duval and Franklin now returned to England.

During the First World War she applied to work with Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray in a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. The offer was rejected and on 28th September 1915 she married Hugh Franklin in the West London Synagogue. His father disinherited him for marrying out of the Jewish faith and never saw him again.

Elsie Duval became ill during the influenza epidemic and died of heart failure on 1st January 1919. It is believed that her heart had been weakened by the treatment she received in prison.

On this day in 1902 Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was born in Adelsheim, Germany. After leaving school she worked as a nurse in Berlin. She married a postal worker at the age of eighteen. Both of them joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) and he died of a heart-attack at a Nazi Rally. According to a later newspaper report: "Her first husband died and left her with six children. Two of the children died. She worked to bring up the others."

In 1929 Scholtz-Klink, became leader of the women's section in Baden. She was a fine orator and became deputy leader of the National Socialist Frauenschaft. Louis L. Snyder described her as "an able, energetic worker and the mother of four children... and was active in labour organizations."

Scholtz-Klink consistently argued against women becoming involved in politics. She suggested that female members of the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) had set a bad example in the Reichstag: "Anyone who has seen the Communist and Social Democratic women scream on the street and the parliament, realize that such an activity is not something which is done by a true woman". She claimed that for a woman to be involved in politics, she would either have to "become like a man", which would "shame her sex".

When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 he appointed Scholtz-Klink as Reich Women's Leader and head of the Nazi Women's League. Scholtz-Klink's main task was to promote male superiority and the importance of child-bearing. In one speech she pointed out that: "Woman is entrusted in the life of the nation with a great task, the care of man, soul, body, and mind. It is the mission of woman to minister in the home and in her profession to the needs of life from the first to last moment of man's existence. Her mission in marriage is... comrade, helper and womanly complement of man - this is the right of woman in the New Germany."

Cate Haste, the author of Nazi Women (2001) has pointed out: "Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was thought to have all the qualifications of the Nazi ideal woman. Trim and neat, her blonde hair braided in plaits, without make-up, a kinderreich mother, she proceeded to educate women in their proper duties to the state, transforming women's groups into agents of indoctrination in Nazi ideology." Scholtz-Klink's role was overseen by Hitler's director of national welfare, Erich Hilgenfeldt. He held ultimate responsibility for the direction, policy and activities of the women's organizations. One of the first statements he made after his appointment "was to leave all policy-making to men."

In July 1934 Scholtz-Klink was appointed as head of the Women's Bureau in the German Labour Front. She now had responsibility for persuading women to work for the good of the Nazi government. In August 1933 a law was passed that enabled married couple to obtain loans to set up homes and start families. However, if they accepted this money the woman had to promise not to seek re-employment. To pay for these loans single men and childless couples were taxed more heavily.

The decline in unemployment after the Nazis gained power meant that it was not necessary to force women out of manual work. However, action was taken to reduce the number of women working in the professions. Married women doctors and civil servants were dismissed in 1934 and from June 1936 women could no longer act as judges or public prosecutors. Hitler's hostility to women was shown by his decision to make them ineligible to jury service because he believed them to be unable to "think logically or reason objectively, since they are ruled only by emotion."

Scholtz-Klink was also placed in charge of the Nazi Mother Service. The organization issued a statement explaining its role in Nazi Germany: "The purpose of the National Mother Service is political schooling. Political schooling for the woman is not a transmission of political knowledge, nor the learning of Party programs. Rather, political schooling is shaping to a certain attitude, an attitude that out of inner necessity affirms the measures of the State, takes them into women's life, carries them out and causes them to grow and be further transmitted."

In September 1937 Scholtz-Klink was interviewed by The New York Times. "One meets her surrounded by Nazi flags and uniforms. Her gentle femininity is a startling contrast to the military atmosphere. She is a friendly woman in her middle thirties, blonde, blue-eyed, regular featured, slender. She sits in a wicker chair on her little balcony and chats with her visitor. Her complexion is so fresh and clear that she dares to do without powder or rouge. She talks, and one notes that her own, capable hands have known hard work.... She has had little time for education; her training for her present position came through hard work and party experience... What does she hope to accomplish for German women in the next ten years? She laughs and cannily refuses to commit herself. She turns to the orthodox National Socialist viewpoint when birth control is mentioned, education for women, the old Feminist movement and working women's problems. Does she feel that her hard-won accomplishments for German women will be swept away in another war? Again she will not commit herself."

Traudl Junge argued that many young women were turned off Nazism by the image projected by Scholtz-Klink. "The Führerin Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was the type we did not like at all. She was just bourgeois and she was so ugly and wasn't fashionable at all. So that was why we didn't bother about joining her organization... It didn't touch me or my friends very much... We were interested in dancing and ballet, and I didn't care much for politics." Junge did not like the message that young women should not wear make-up and had to be "naturally beautiful, sporty and healthy, and giving her leader (Hitler) a lot of children."

Hitler's government gradually changed its attitude towards women in the work-force. With the build-up for war, it now needed married women to seek employment in industry. In 1937 it rescinded its stipulation that women qualified for marriage loans only if they undertook not to enter the labour market. Gertrud Scholtz-Klink as Reich Women's Leader, issued a statement that said: "It has always been our chief article of fact that woman's place is in the home - but since the whole of Germany is our home we must serve her wherever we can best do so." In 1938 she argued that "the German woman must work and work, physically and mentally she must renounce luxury and pleasure." However, she admitted in 1938 that she "had not once had the chance to discuss women's affairs in person with the Führer."

In 1940, Scholtz-Klink was married to her third husband SS-Obergruppenführer August Heissmeyer, and made frequent trips to visit women at concentration camps for women at Moringen, Lichtenburg, and Ravensbrück. Her husband was later convicted of war crimes.

Martin Bormann suggested that the army should form women's battalions during the war. Scholtz-Klink was always against the idea of women serving in the army. She argued: "I have sons in the war, I will protect my daughters." Despite her opposition in 1942 women were assigned to military duties as "Female Wehrmacht Auxiliaries". Scholtz-Klink received support from Dr. Jutta Rüdiger, the head of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls): "It is out of the question. Our girls can go right up to the front and help them there, and they can go everywhere, but to have a women's battalion with weapons in their hands fighting on their own, that I do not support. It's out of the question. If the Wehrmacht can't win this war, then battalions of women won't help either." Baldur von Schirach said "Well, that's your responsibility". Rüdiger retorted: "Women should give life and not take it. That's why we were born." However, when the Red Army was advancing towards in Berlin in 1945 Rüdiger instructed BDM leaders to learn to use pistols for self-defence.

At the end of the Second World War Sholtz-Klink went into hiding near Tübingen with her husband using the names Heinrich and Maria Stuckebrock. However, on 28th February 1948, the couple were identified and arrested. She was released from prison in 1953. Her book, The Woman in the Third Reich, was published in 1978.

Gertrud Scholtz-Klink died on in in Bebenhausen on 24th March 1999.

On this day 1907 Philippa Strachey of the NUWSS organised the largest demonstration in its history. The United Procession of Women, was a peaceful demonstration where more than three thousand women marched from Hyde Park Corner to the Strand in support of women's suffrage. Women from all classes participated in what was the largest public demonstration supporting women's suffrage seen up to that date. It acquired the name "Mud March" from the day's weather, when incessant heavy rain left the marchers drenched and mud-spattered.

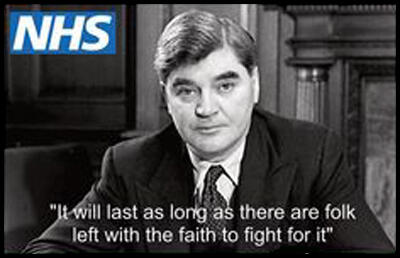

On this day in 1948 Aneurin Bevan made a speech in the House of Commons on the National Health Service. "We have provided paid bed blocks to specialists, where they are able to charge private fees (Labour MPs shout "shame"). I agree at once that these are very serious things, and that, unless properly controlled, we can have a two-tier system in which it will be thought that members to the general public will be having worse treatment than those who are able to pay."

Some members of the medical profession opposed the government's plans. Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA) mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. The main complaint of the BMA was that the NHS would "turn doctors from free-thinking professionals into salaried servants of central government". At a BMA a doctor was "cheered to the rooftops" when he said the NHS was "strongly suggestive of the Hitlerite regime" in Nazi Germany.

The right-wing national press was opposed to the idea of a National Health Service. The Daily Sketch reported: "The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion."

Winston Churchill led the attack on Aneurin Bevan. In one debate in the House of Commons he argued that unless Bevan "changes his policy and methods and moves without the slightest delay, he will be as great a curse to his country in time of peace as he was a squalid nuisance in time of war." The Conservative Party voted against the measure. The Tory ammendment stated that it "declines to give a Third Reading to a Bill which discourages voluntary effort and association; mutilates the structure of local government; dangerously increases minisaterial power and patronage; approppriates trust funds and benefactions in contempt of the wishes of donors and subscribers; and undermines the freedom and independence of the medical profession to the detriment of the nation." However, on 2th July, 1946, the Third Reading was carried by 261 votes to 113. Michael Foot commented that the Conservatives had voted against the "most exciting and popular of the Government's measures a bare four months before it was to be introduced".

David Widgery, the author of The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988) admitted that "the Act was bold in outline; a National Health Service entirely free at the time of use, financed out of general taxation and able to organise preventive medicine, research and paramedical aids on a national basis... Bevan himself was apparently well prepared to deal with conservative pressures, and he was quite prepared for the out-break of near-hysteria by doctors, skilfully orchestrated by Charles Hill of the BMA, who had endeared himself to the listening public during the war as the smooth-spoken, concerned Radio Doctor."

Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA), led by Charles Hill, mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. One doctor was cheered at a BMA meeting for saying that the proposed NHS bill was "strongly suggestive" of what had been going in Nazi Germany.

By July 1948, Aneurin Bevan had guided the National Health Service Act safely through Parliament. The Government resolution was carried by 337 votes to 178. Niall Dickson has pointed out: "The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums... Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio. Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters. Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions."

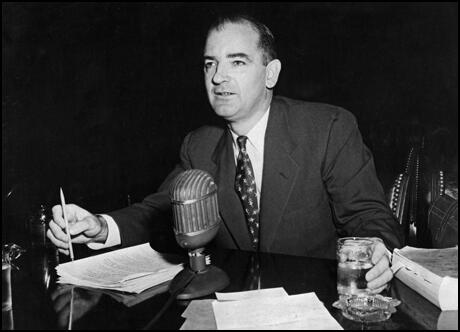

On this day in 1950 Joseph McCarthy, a senator from Wisconsin, made a speech claiming to have a list of 205 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party (later he reduced this figure to 57). The list of names was not a secret and had been in fact published by the Secretary of State in 1946. These people had been identified during a preliminary screening of 3,000 federal employees. Some had been communists but others had been fascists, alcoholics and sexual deviants. If screened, McCarthy's own drink problems and sexual preferences would have resulted in him being put on the list.

McCarthy also began receiving information from his friend, J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). William C. Sullivan, one of Hoover's agents, later admitted that: "We were the ones who made the McCarthy hearings possible. We fed McCarthy all the material he was using."

With the war going badly in Korea and communist advances in Eastern Europe and in China, the American public were genuinely frightened about the possibilities of internal subversion. McCarthy, was made chairman of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate, and this gave him the opportunity to investigate the possibility of communist subversion.

For the next two years McCarthy's committee investigated various government departments and questioned a large number of people about their political past. Some lost their jobs after they admitted they had been members of the Communist Party. McCarthy made it clear to the witnesses that the only way of showing that they had abandoned their left-wing views was by naming other members of the party.

This witch-hunt and anti-communist hysteria became known as McCarthyism. Some left-wing artists and intellectuals were unwilling to live in this type of society and people such as Joseph Losey, Richard Wright, Ollie Harrington, James Baldwin, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole and Chester Himes went to live and work in Europe.

At first Joseph McCarthy mainly targeted Democrats associated with the New Deal policies of the 1930s. Harry S. Truman and members of his Democratic administration such as George Marshall and Dean Acheson, were accused of being soft on communism. Truman was portrayed as a dangerous liberal and McCarthy's campaign helped the Republican candidate, Dwight Eisenhower, win the presidential election in 1952.

After what had happened to McCarthy's opponents in the 1950 elections, most politicians were unwilling to criticize him in the Senate. As The Boston Post pointed out: "Attacking him is this state is regarded as a certain method of committing suicide." One notable exception was William Benton, the owner of Encyclopaedia Britannica, and a senator from Connecticut. McCarthy and his supporters immediately began smearing Benton. It was claimed that while Assistant Secretary of State, he had protected known communists and that he had been responsible for the purchase and display of "lewd art works". Benton, who was also accused of being disloyal by Joseph McCarthy for having much of his company's work printed in England, was defeated in the 1952 elections.

On this day in 1968 Sydney Silverman died. Silverman, the son of a draper, was born in Liverpool on 8th October 1895. The family were very poor and two of the four children died before reaching adulthood. According to his biographer, Sarah McCabe: "The Silvermans were poor, but their poverty was not that of nineteenth-century industrial labour, for Myer Silverman was a pedlar or, more properly, a chapman, who lived as a small-time entrepreneur among his labouring fellows. He was never materially successful, probably because his sympathy for his impoverished customers did not allow him to enrich himself at their expense."

Silverman was extremely intelligent and obtained a scholarship to the Liverpool Institute, a leading grammar school in the city. This was followed by two further scholarships, one to the University of Liverpool and the other to Oxford University. However, he could not afford the expense of an Oxford scholarship and decided to take up the Liverpool offer and began his studies in English literature.

In 1916 the government introduced military conscription. Silverman, a pacifist, refused to join the British Army during the First World War. Influenced by the views of Bertrand Russell he registered as a conscientious objector, Silverman served several prison sentences for his beliefs. His son Paul later said: "His idea was that the workers of the world should unite: if the ordinary men on both sides refused to join the armies, the powers-that-be couldn't have had a war. But when war was declared everyone seemed to be infected with war fever and my father found himself very much in a minority."

Another son, Roger Silverman, commented: " Dad was taken to the military barracks but when he got there he wouldn't obey orders and so was arrested and court-martialled. In 1917 he was sentenced to two years of hard labour, and put in prison in Preston." He was later transferred to Wormwood Scrubs. Silverman's experiences in prison made him an advocate of penal reform.

After the war was over Silverman returned to University of Liverpool to complete his studies. In 1921 he successfully applied for a teaching post at the University of Helsinki. Silverman returned to England in 1925 and after further studies he eventually qualified as a solicitor in 1927. Over the next few years he developed a reputation as a solicitor who was willing to defend the interests of the poor in Liverpool. This included workmen's compensation claims and landlord-tenant disputes.

Sydney Silverman married Nancy Rubinstein, whose family had fled to Liverpool from the Russian pogroms in the late nineteenth century. Nancy, like her father, was a talented musician. Over the next few years the couple had three sons, Paul, Julian and Roger.

A member of the Labour Party, Silverman was elected as a city councillor in 1932. Soon afterwards he was adopted as the parliamentary candidate for Nelson and Colne and entered the House of Commons following the 1935 General Election. Silverman was one of the leading opponents of Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. By 1935 Mosley was expressing strong anti-Semitic views and provocative marches through Jewish districts in London led to riots. Silverman was one of those who supported The passing of the 1936 Public Order Act that made the wearing of political uniforms and private armies illegal, using threatening and abusive words a criminal offence, and gave the Home Secretary the powers to ban marches.

Silverman retained his pacifists views until he discovered what was happening to the Jews in Nazi Germany. He therefore gave his full support to Britain's involvement in the Second World War. However, he was critical of Winston Churchill who promoted the policy of "unconditional surrender", and argued that carefully drafted peace aims would end the war more quickly.

When the Labour Party won the 1945 General Election Silverman was expected to be offered a post in the new government. However, Silverman held strong left-wing opinions and Clement Attlee decided against offering him a job. According to the historian, Ben Pimlott, there were other reasons for this decision. Silverman and Ian Mikardo were not given posts because they "belonged to the Chosen People, and he didn't think he wanted any more of them."

Over the next few years Silverman became highly critical of Ernest Bevin and his role as foreign secretary. He was particularly upset by his dealings with the Soviet Union. His biographer, Sarah McCabe, has argued: "Silverman fiercely criticized the foreign secretary's handling of relations with the Soviet Union, for he claimed that Bevin negotiated with Russia as if it were the Communist Party which, in Britain, was both feared and despised; instead he thought that the Soviet Union embodied a great people whose rights and dignity should be respected."

Silverman was a strong opponent of capital punishment and in 1948 managed to persuade the House of Commons to agree to a five year suspension of executions. However, this clause in the Criminal Justice Bill was defeated in the House of Lords. As a result Silverman founded the Campaign for the Abolition of the Death Penalty. In 1953 he published his book, Hanged and Innocent?

In November 1954 Silverman, Michael Foot, and three others were expelled from the Labour Party for opposing its nuclear defence policy. Three years later Silverman joined with Kingsley Martin, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Vera Brittain, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Silverman continued to campaign against capital punishment and in 1956 he introduced a private member's Bill for abolition. Once again it was defeated in the House of Lords. Silverman refused to be beaten and as Ian Mikardo has pointed out, Silverman was "incomparably courageous in espousing unpopular causes and facing down a hostile audience." Joseph Mallalieu was less complimentary: "Of all the House of Commons personalities, the most irritating is perhaps Mr Sydney Silverman. He is a cocky man, who throws his shoulders back as if to swell his chest, and thrusts his now bearded chin outward and upward, as if to give him inches. Indeed, he seems over-occupied with his own shortness."

In the 1964 General Election Silverman was returned to the House of Commons with an increased majority despite the fact that one of the candidates, although professedly Labour, made his platform the return of capital punishment for all murder. Harold Wilson, the new prime minister, was also an opponent of the death penalty and his Labour government agreed to introduce legislation to abandon capital punishment for five years. With overwhelming support in the Commons the Lords agreed to pass the measure.

His biographer, Sarah McCabe, has argued: "Silverman had a passion for justice and equality that kept him well to the left of his party, so that he did not commend himself to the establishment. Besides, he was not good at collective action; most of his battles he fought alone, for he enjoyed twisting the tails of his antagonists and might have been denied this enjoyment if he had worked with others." According to his colleague, Richard Crossman: "Silverman was vain, difficult and uncooperative. No one could get him to work in any kind of a group. All his life he remained an individualist back-bencher."