On this day on 8th March

On this day in 1848 journalist Frank Wilkeson was born in Buffalo, New York State. He was the youngest son of the journalist, Samuel Wilkeson (1817-1889), and Catherine Cady, the sister of Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Samuel Wilkeson covered the American Civil War for the New York Times. Meanwhile, the 14 year old Frank ran away from home and on 26th March, 1864 joined the Union Army. Claiming he was an eighteen year old farmer, Wilkeson enlisted in the 11th Battery of New York Light Artillery.

Wilkeson was sent to Northern Virginia where he took part in the military campaign led by General Ulysses S. Grant. This included Wilderness (May, 1864) and Petersburg (June, 1864). On 21st June, 1864, Wilkeson was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Artillery. He was sent to Washington and later he led a unit guarding prisoners in Elmira. Wilkeson left the army in March, 1866.

Wilkeson worked as a mining engineer in Pennsylvania and after marrying Mary Crouse in 1869, the couple settled in Johnstown. In 1871 they moved to Gypsum, Kansas, where they managed a large cattle ranch and wheat farm.

In the 1880s Wilkeson wrote for several newspapers including the New York Times. A book on his military experiences, Turned Inside Out: Recollections of a Private Soldier was published in 1887.

Frank Wilkeson died at Chelan, Washington, on 22nd April, 1913.

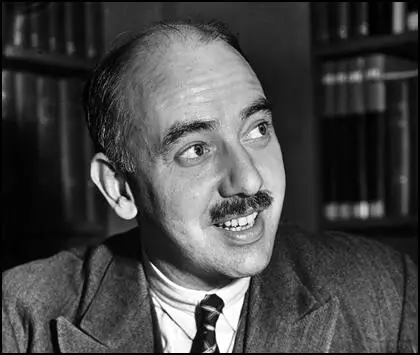

On this day in 1879 Otto Hahn, the son of a glazier, was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. He studied chemistry at the University of Marburg and obtained his doctorate in 1901. Afterwards he became a lecturer at the university.

In 1904 he went to London to study at University College where he carried out research into radioactivity. He later moved to Montreal where he worked under Ernest Rutherford.

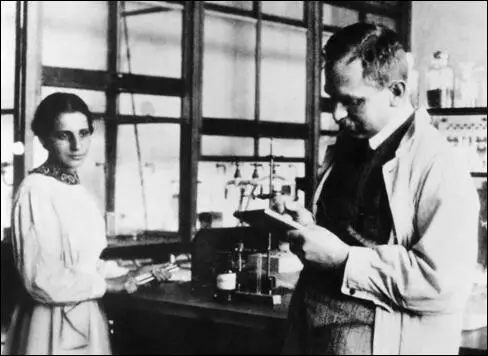

Rutherford returned to Germany in 1906 where he began work with Lise Meitner at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. Hahn now became head of the radiochemistry department.

On the outbreak of the First World War Hahn was recruited into the German Army. His scientific knowledge was acknowledged and he became a chemical-warfare specialist and organized the use of Chlorine Gas and Mustard Gas against British and French troops.

After the war Hahn resumed working with Lise Meitner and together they discovered protactinium (1918) and nuclear isomers (1921). Over the next few years they devoted their time to researching the application of radioactive methods to chemical problems.

In the 1930s Hahn became interested in the research being carried out by Enrico Fermi and Emilio Segre at the University of Rome. This included experiments where elements such as uranium were bombarded with neutrons. By 1935 the two men had discovered slow neutrons, which have properties important to the operation of nuclear reactors.

Hahn and Lise Meitner were now joined by Fritz Strassmann and discovered that uranium nuclei split when bombarded with neutrons. In 1938 Meitner, like other Jews in Germany, was dismissed from her university post. She moved to Sweden and in 1939 wrote a paper on nuclear fission with her nephew, Otto Frisch, where they argued that by splitting the atom it was possible to use a few pounds of uranium to create the explosive and destructive power of many thousands of pounds of dynamite.

During the Second World War Hahn and Fritz Strassmann continued to work in the field of nuclear physics but they made no attempt to turn their knowledge into a military weapon. Hahn had a strong dislike for Adolf Hitler and his government and told a friend: "If my work would lead to Hitler having an atomic bomb I would kill myself."

In April, 1945, Allied forces arrested German scientists such as Hahn, Werner Heisenberg, Carl von Weizsacker, Max von Laue, Karl Wirtz, and Walter Gerlach. These men were now taken to England where they were questioned to see if they had discovered how to make atomic weapons.

When he was released Hahn became president of the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. In 1966 Hahn shared with Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann the Enrico Fermi Award. Otto Hahn died in West Germany on 28th July, 1968.

On this day in 1887 Henry Ward Beecher died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Henry Ward Beecher, the eighth son of the Rev. Lyman Beecher, was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, on 24th June, 1813. The brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, he was educated at the Lane Theological Seminary before becoming a Presbyterian minister in Lawrenceburg (1837-39) and Indianapolis (1839-47). His pamphlet, Seven Lectures to Young Men, was published in 1844.

Beecher moved to Plymouth Church, Brooklyn in 1847. By this time he had developed a national reputation for his oratorical skills, and drew crowds of 2,500 regularly every Sunday. He strongly opposed slavery and favoured temperance and woman's suffrage.

Beecher condemned the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska bill from his pulpit and helped to raise funds to supply weapons to those willing to oppose slavery in these territories. These rifles became known as Beecher's Bibles. John Brown and five of his sons, were some of the volunteers who headed for Kansas.

He supported the Free Soil Party in 1852 but switched to the Republican Party in 1860. During the Civil War Beecher's church raised and equipped a volunteer regiment. However, after the war, he advocated reconciliation.

Beecher edited The Independent (1861-63) and the Christian Union (1870-78) and published several books including the Summer in the Soul (1858), Life of Jesus Christ (1871), Yale Lectures on Preaching (1872) and Evolution and Religion (1885).

On this day in 1889 Lilla Harvey-Smith, the 8th of 11 children of Lizzie Harrison (1856-1909) and the Rev. William Harvey-Smith (1851-1923), was born in Hackney, London, on 8th March 1889.

Lilla was a student at Eltham Training College, spending her holidays with a number of others in an household headed by her brother Alfred Harvey-Smith, a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Lilla also joined the ILP and was active in the struggle for women's suffrage. After leaving college she worked as a Elementary School Teacher. In 1911 Lilla Harvey-Smith was living with at 60 Myddleton Square, London E.C., with her brother Harry Harvey-Smith and two of her unmarried sisters, Violet and Daisy Harvey-Smith, plus 3 cousins and two female friends.

Lilla began a relationship with Fenner Brockway. Lilla was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and as Brockway pointed out in his autobiography, Inside the Left (1942): "The women's suffrage movement still had my enthusiasm hardly less than the Socialist movement. When the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies threw in its lot with the Labour Party, and particularly with the ILP, I spoke at their meetings frequently and took part in a number of their by-election campaigns."

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This Women Social & Political Union took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

On 20th August 1914, Lilla married Fenner Brockway, the editor of the ILP's newspaper, The Labour Leader. They were both opposed to the First World War and over the first few weeks of the conflict exchanged letters through Sweden with Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin and Karl Liebknecht where they discussed the failure of the Second International to prevent a European war.

The couple feared the introduction of conscription. Lilla Brockway suggested that a letter should be published in the newspaper suggesting an organisation that was opposed to conscription. On 12 November 1914 a letter appeared in the Labour Leader: "Although conscription may not be so imminent as the Press suggests, it would perhaps be well for men of enlistment age who are not prepared to take the part of a combatant in the war, whatever be the penalty for refusing to band themselves together as we may know our strength. As a preliminary, if men between the years of 18 and 38 who take this view will send their names and addresses to me at the addresses given below a useful record will be at our service."

There was a great response to the letter and 150 people joined the organisation, the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) in the first six days. A follow-up letter was published on 3rd December: "Whilst there may not be any immediate danger of conscription, nothing is more uncertain than the duration and development of the war, and it would, we think, be as well of men of enlistment age (19 to 38) who are not prepared to take a combatant's part, whatever the penalty for refusing, formed an organisation for mutual counsel and action. Already, in response to personal appeals, a large number of names have been forwarded for registration, and many correspondents have expressed a desire for knowledge of, and fellowship with others who have come to the same determination not to fight. To meet these needs 'The No-Conscription Fellowship' has been formed, and we invite men of recruitment age who have decided to refuse to take up arms to join.

Lilla Brockway became the honorary Secretary of the NCF, until early in 1915 when an office was opened in London to handle the growing membership. (11) By October 1915 it claimed 5,000 members. Members of the NCF included Clifford Allen, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, C. E. M. Joad, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Herbert Morrison, Maude Royden, Ramsay MacDonald, Rev. John Clifford, Helena Swanwick, Catherine Marshall, Kathleen Courtney, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Catherine Marshall, Alfred Mason, Winnie Mason, Alice Wheeldon, William Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Hettie Wheeldon, Storm Jameson, Ada Salter, and Max Plowman.

Violet Tillard was appointed General Secretary of the No-Conscription Fellowship, She would visit men in prison. Corder Catchpool later recalled that she was "of inspiration in personal contact, and of strong, quiet leadership in common counsel... Violet Tillard was the first, except one member of my own family, to greet me on my release from prison, and I shall never forget her welcome."

In December 1914 Lilla Brockway joined forces with Emily Hobhouse, Margaret Bondfield, Helena Swanwick, Maude Royden, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Ada Salter, Isabella Ford, Elsie Duval Franklin and Marion Phillips to write an open letter to the women of Germany and Austria. "Some of us wish to send you a word at this sad Christmastide… Though our sons are sent to slay each other, and our hearts are torn by the cruelty of this fate, yet through pain supreme we will be true to our common womanhood. We will let no bitterness enter in this tragedy, made sacred by the life-blood of our best, nor mar with hate the heroism of their sacrifice. Though much has been done on all sides you will, as deeply as ourselves, deplore, shall we not steadily refuse to give credence to those false tales so freely told us, each of the other? Do you not feel with us that the vast slaughter in our opposing armies is a stain on civilisation and Christianity and that still deeper horror is aroused at the thought of those innocent victims, the countless women, children, babes, old and sick, pursued by famine, disease, and death in the devastated areas, both East and West? Peace on earth is gone, but by renewal of our faith that it still reigns at the heart of things. Christmas should strengthen both you and us and all womanhood to strive for its return."

In 1915 the family moved to London, where Fenner Brockway became the No-Conscription Fellowship secretary, renting a room in Bryanston Square, with the baby Frances, sleeping in a drawer. Horatio Bottomley, the editor of the John Bull Magazine wrote a full page article demanding Brockway's arrest and execution. In November, 1916, Fenner was arrested under the Military Service Act and Lilla and the baby were evicted from the room.

Lilla Brockway kept in contact with other pacifists. In January 1928 she wrote a letter to Mahatma Gandhi. "I would clearly love to visit India. I know there are terrible evils and sufferings there, but I know too, that there are wonderful, beautiful souls and the deep spiritual calm for which my own soul longs, in the stupid civilised (?) country of ours."

Lilla Brockway gave birth to four children Frances (1915), Margaret (1917), Joan (1921) and Olive (1924). According to Lilla the marriage was happy until 1929. "Then she noticed a change in her husband's attitude to her. She became deaf at that time, and it irritated him to have to shout to make her hear. He was then general secretary of the ILP. He confessed that he had been unfaithful to her, but she forgave him. Later he went on a lecture tour to America and he informed her that he was in love with another woman. He asked her to divorce him but she replied that she could not as it would break the hearts of their three children."

Fenner Brockway was having a relationship with Edith Violet King, a Clerical Assistant. In 1939 they were living at 10 Neville's Court, Chancery Lane, London. Whereas Lilla was living in Sevenoaks Road, Sevenoaks, Kent, carrying out "unpaid domestic duties".

Lilla Brockway, now living at Hosey Hill, Westerham, Kent, obtained a divorce "on the grounds of the misconduct of her husband" in July, 1945.

Lilla Brockway died in Maidstone, Kent, in 1974.

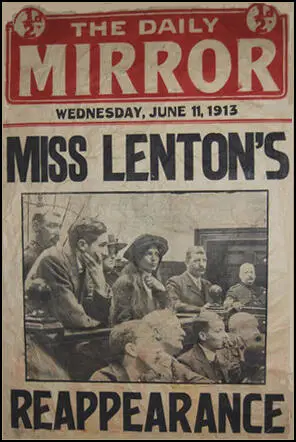

On this day in 1913 the Morning Post reported on the trial of Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry accused of setting fire to the tea pavilion in Kew Gardens. In court it was reported: "The constables gave chase, and just before they caught them each of the women who had separated was seen to throw away a portmanteau. At the station the women gave the names of Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry. In one of the bags which the women threw away were found a hammer, a saw, a bundle to tow, strongly redolent of paraffin and some paper smelling strongly of tar. The other bag was empty, but it had evidently contained inflammables."

In July 1912, Christabel Pankhurst began organizing a secret arson campaign. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

One of the first arsonists was Mary Richardson. She later recalled the first time she set fire to a building: "I took the things from her and went on to the mansion. The putty of one of the ground-floor windows was old and broke away easily, and I had soon knocked out a large pane of the glass. When I climbed inside into the blackness it was a horrible moment. The place was frighteningly strange and pitch dark, smelling of damp and decay... A ghastly fear took possession of me; and, when my face wiped against a cobweb, I was momentarily stiff with fright. But I knew how to lay a fire - I had built many a camp fire in my young days -a nd that part of the work was simple and quickly done. I poured the inflammable liquid over everything; then I made a long fuse of twisted cotton wool, soaking that too as I unwound it and slowly made my way back to the window at which I had entered."

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

In 1913 the WSPU arson campaign escalated and railway stations, cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire. Slogans in favour of women's suffrage were cut and burned into the turf. Suffragettes also cut telephone wires and destroyed letters by pouring chemicals into post boxes. The women responsible were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act.

Kitty Marion was a leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign and she was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House in St Leonards in April 1913. Two months later she and 26 year old Clara Giveen were told that the Grand Stand at the Hurst Park racecourse "would make a most appropriate beacon". The women returned to a house in Kew. A police constable who had been detailed to watch the house, saw the two women return and during the course of the next morning they were arrested. Their trial began at Guildford on 3rd July. She was found guilty and sentenced to three years' penal servitude. She went on hunger strike and was released under the Cat & Mouse Act. She was taken to the WSPU nursing home, into the care of Dr. Flora Murray and Catherine Pine.

As soon as Kitty Marion recovered she went out and broke a window of the Home Office. She was arrested and taken back to Holloway Prison. After going on hunger strike for five days she was again released to a WSPU nursing home. According to her own account, she now set fire to various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred. It has been calculated that Kitty Marion endured 232 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike.

Although Elizabeth Robins and Octavia Wilberforce disapproved of Kitty Marion's arson campaign they used their 15th century farmhouse at Backsettown, near Henfield, as a hospital and helped her recover from her various spells in prison and the physical effects of going on hunger strike. On 31st May 1914, with the help of Mary Leigh, escaped to Paris.

On this day in 1917 (23rd February in the old Russian calendar) women workers in Petrograd begin a demonstration demanding "Bread and Peace". It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Arthur Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges."

The slogans on the banners were patriotic but also made forceful demands for change: "Feed the children of the defenders of the motherland," read one; another said: "Supplement the ration of soldiers' families, defenders of freedom and the people's peace." The city's governor, Alexander Pavlovich Balk, said they consisted of "ladies from society, lots more peasant women, student girls and, compared with earlier demonstrations, not many workers".

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working in Petrograd, with strong left-wing opinions, wrote to his aunt, Anna Maria Philips, claiming that the country was on the verge of revolution: "Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps."

Leon Trotsky wrote "23rd February (8th March) was International Woman's Day and meetings and actions were foreseen. But we did not imagine that this 'Women's Day' would inaugurate the revolution. Revolutionary actions were foreseen but without a date. But in the morning, despite the orders to the contrary, textile workers left their work in several factories and sent delegates to ask for the support of the strike… which led to mass strike... all went out into the streets."

It has been argued that the Russian Revolution was begun by women, not male workers. This demonstration inspired International Women's Day. An event that adopted by the United Nations in 1977. This is a global day celebrating the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women. The day also marks a call to action for accelerating gender parity. Significant activity is witnessed worldwide as groups come together to celebrate women's achievements or rally for women's equality.

On this day in 1917 Ferdinand von Zeppelin died. Ferdinand von Zeppelin was born in Baden, Germany in 1838. When he was twenty he joined the German Army and was a member of the expedition that went to North America to search for the source of the Mississippi River. While in Minnesota in 1870 he made his first ascent in a military balloon.

Zeppelin had reached the rank of brigadier general when he retired from the German Army in 1891. Over the next few years he devoted himself to to the study of aeronautics.

In 1894 the German government rejected his proposals for a lighter-than-air flying machine. Although now aged sixty, Zeppelin decided to invest all his own money in a company producing airships.

By 1898 Zeppelin, with a team of 30 workmen, had assembled his first airship. The main principle of Zeppelin's invention was that hydrogen-filled gas-bags were carried inside a steel skeleton. The airship, which weighed 12 tons and contained 400,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, was driven by propellers connected by two 15-hp Daimler engines. After the Zeppelin LZ made its first flight on 2nd July 1900, the German government decided to help fund the project.

By the outbreak of the First World War the German Army owned seven of Zeppelin's airships. These Zeppelins could reach a maximum speed of 136 kph and reach a height of 4,250 metres. They had five machine-guns and could carry 2,000 kg (4,400 lbs) of bombs.

In the war Zeppelins were used for air rids on Britain and France. However, being large and slow, they were an easy target and by the summer of 1917 the German military had decided to employ them for transporting supplies.

On this day in 1941 novelist Sherwood Anderson died of peritonitis in Panama. Anderson, the third of seven children, was born in Camden, Ohio in 1876. He left school at 14 and after various jobs served in the Spanish-American War (1898-9).

After leaving the US Army, Anderson worked as a manager of a paint factory in Elyria, Ohio. In 1908 he began writing short stories and novels. He moved to Chicago where he found work in an advertising agency. Anderson became friends with other writers in Chicago such as Floyd Dell, Theodore Dreiser, Ben Hecht and Carl Sandburg.

Anderson shared his friends radical political views and in 1914 and began having his work published in The Masses, a socialist journal edited by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman. This included the stories about small-town life that were subsequently published as Winesburg, Ohio.

Anderson's first novel, Windy McPherson's Son was published in 1916. This was followed by the novel, Marching Men (1917) and a collection of prose poems, Mid-American Chants (1918). Winesburg, Ohio (1919), Anderson's most important work, was published in 1919. The book, a collection of 23 inter-related stories of small-town life, features George Willard, a reporter for the local newspaper, who has ambitions to become a famous writer.

Other books published by Anderson during this period included Poor White (1920), The Triumph of the Egg (1921), Many Marriages (1923) and Horses and Men (1923). Although considered to be a minor work by the critics, Anderson's most commercial successful novel was Dark Laughter (1925).

Sherwood Anderson, whose autobiography, A Story Teller's Story, was published in 1924, failed to recapture the standard of the work produced in Winesburg, Ohio. His later work such as Tar: A Midwest Childhood (1926), Beyond Desire (1932) and Death in the Woods (1933) failed to make an impact on critics or the book-buying public.

On this day in 1945 Iris Carpenter reports on the Red Army and the US Army joining up for the first time. Iris Carpenter, the daughter of a cinema entrepreneur, was born in England in 1906. She became a journalist and worked as a film critic for the Daily Express. After her marriage to Charles Scruby she retired from journalism and gave birth to two children.

During the Second World War she joined the Daily Herald and wrote about the Blitz in London. When she was refused permission to cover the war in Europe, she moved to the United States and became a war correspondent with The Boston Globe.

Carpenter accredited to the First United States Army and arrived in France four days after the D-Day landings. Soon afterwards she got into trouble with the authorities after visiting the Cherbourg beachhead without a proper military escort. As a result Carpenter and other women reporters were placed under the command of the Public Relations Division and were told they could not visit the front-line. This directive was later changed and along with Tania Long, Ann Stringer and Catherine Coyne she was allowed to travel with the 1st Army and reported the war in France, Holland, Belgium and Germany.

Carpenter was also at Torgau when the Red Army and the US Army joined up for the first time. Jack Hazard of the The Boston Globe later commented: "She has made several scoops of real news that men missed, because of her daring, enthusiasm, originality and scorn of personal comfort." She was also with the troops when they liberated Buchenwald and Dachau.

According to Time Magazine: "Her reports from the front lines and hospitals in France and Germany described in graphic prose some of the bloodiest fighting on the Western front, including the Battle of the Bulge as well as the liberation of Nazi concentration camps; remained in the U.S., working for Voice of America."

After the war she married Colonel Russell F. Akers of the First United States Army. Her book, No Woman's World, was published in 1946.

On this day in 1966 Konni Zilliacus makes speech in the House of Commons on defence spending: "One third of Britain's budget is on defence. I suggest that the price is too high ... I think that we can render better service to peace by scaling down our armaments to the point where we are solvent and can get on with our Socialist reconstruction, rather than by lowering the standard of living of our people and staggering into national bankruptcy under the burden of huge armaments. Since the general election there has been no sign of any realistic insight into what is happening in the world, no sober appraisal of our own position or the limitations of our power ... We have sunk into ancient ruts, running back to the nineteenth century, and punctuated by two world wars. We are trying to make the ghost of Palmerston walk again."

On this day in 1985 Ralph Ingersoll died in Miami Beach, Florida. Ralph McAllister Ingersoll was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on 8th December, 1900. He was educated at Yale University and after graduating After leaving school he worked as a mining engineer in California.

In 1923 he moved to New York City and became a reporter for the New York American. Two years later he was recruited by Harold Ross to work as managing editor for The New Yorker. He was such a success that Henry Luce appointed him to do the same job for Time Magazine. He also devised the formula of business magazine Fortune, eventually becoming general manager of the company.

Over the years Ingersoll grew critical of what Henry Luce was trying to do with Time Magazine: "Time's technique for handling news is so simple that it seems to have eluded several generations of critics and yet it is almost solely responsible for (A) Time's monumental commercial success and (B) Time's equally monumental failure in the fields of ethics, integrity, and responsibility. The problem Henry R. Luce and the late Briton Hadden tackled when they set out to invent their new kind of weekly news magazine was how to condense a week's news on all fronts: national, international, cultural, and business into a package of words that could be read cover to cover in a couple of hours."

Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. Churchill realised straight away that it would be vitally important to enlist the United States as Britain's ally. Randolph Churchill, on the morning of 18th May, 1940, claims that his father told him "I think I see my way through.... I mean we can beat them." When Randolph asked him how, he replied with great intensity: "I shall drag the United States in." Churchill appointed William Stephenson as head of the British Security Coordination (BSC).

As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention." An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI.

Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) argues that Ernest Cuneo, who worked for British Security Coordination, was "empowered to feed select British intelligence items about Nazi sympathizers and subversives" to friendly journalists such as Ingersoll, Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Walter Lippmann, Dorothy Thompson, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward Murrow, Vincent Sheean, Eric Sevareid, Edmond Taylor, Rex Stout, Edgar Ansel Mowrer and Whitelaw Reid, who "were stealth operatives in their campaign against Britain's enemies in America". Cuneo also worked closely with editors and publishers who were supporters of American intervention into the Second World War. This included Arthur Hays Sulzberger (New York Times), Henry Luce (Time Magazine and Life Magazine), Helen Rogers Reid (New York Herald Tribune), Barry Bingham (Louisville Courier-Journal), Paul C. Patterson (Baltimore Sun) and Dorothy Schiff (New York Post).

Ingersoll felt so strongly about this issue that he established the PM newspaper in New York City. With the financial backing of another supporter of intervention, Marshall Field III, the newspaper began on 18th June, 1940. In its first editorial, that appeared on the front page, Ingersoll wrote: "We are against people who push other people around" and demanded support for the Allies in the Second World War. It accepted no advertising in an attempt to be free of pressure from business interests. It also made use of large photographs and the cartoons of Arthur Szyk and Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss).

PM managed to achieve a circulation of 200,000, however, without the ability to carry advertising, it could only survive with the sponsorship of Marshall Field III, who now owned Chicago Sun, another pro-intervention newspaper. Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998) has argued: "PM never attracted enough circulation to make money, but it was a wonderful propaganda vehicle despite its small circulation. In September, 1940, Field bought out the other backers for twenty cents on the dollar." In a declassified report from British Security Coordination it listed PM as "among those who rendered service of particular value".

After the United States entered the Second World War, Ingersoll, aged 41, joined the US Army. Ingersoll wrote about his experiences in his book, Top Secret (1946). He returned to PM after the war but it was forced to close in 1948.

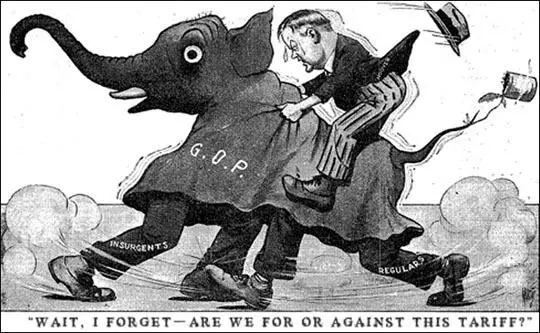

On this day in 2018 Donald Trump announced a plan to impose a 25% tariff on imports of steel, and a 10% tariff on aluminum. The executive order was signed the following day. Trump promised during the presidential campaign to protect US steelworkers’ jobs, but his plan was opposed by top economic adviser Gary Cohn, who argued that the impact on trade and on companies using cheap steel imports would outweigh any benefits of the tariffs. For example, about 6.5m people are employed in the U.S. in businesses that use steel and aluminum. It was no surprise that more than 100 Republican House members signed a letter expressing “deep concern” about the plan. They pressed Trump to change course and “avoid unintended negative consequences to the US economy and its workers”. They added that “tariffs are taxes that make US businesses less competitive and US consumers poorer.”

Trump took this action because of the growing problem with importing too many foreign goods. The United States has the world's largest trade deficit. It's been that way since 1975. The deficit in goods and services was $566 billion in 2017. Imports were $2.895 trillion and exports were only $2.329 trillion. The U.S. trade deficit in goods, without services, was $810 billion. The United States exported $1.551 trillion in goods. The biggest categories were commercial aircraft, automobiles, and food. It imported $2.361 trillion. The largest categories were automobiles, petroleum, and cell phones.

More than 65 percent of the U.S. trade deficit in goods is with China. The $375 billion deficit with China was created by $506 billion in imports. The main Chinese imports are consumer electronics, clothing, and machinery. America only exported $130 billion in goods to China. The U.S. also has a trading deficit with Mexico ($71 billion), Japan ($69 billion), Germany ($65 billion), Canada ($18 billion) and the United Kingdom ($13 billion).

The U.S. has a trading deficit of $92 billion with the European Union. On 10th March, President Trump, using his unusual negotiating style, tweeted: "The European Union, wonderful countries who treat the U.S. very badly on trade, are complaining about the tariffs on Steel & Aluminum. If they drop their horrific barriers & tariffs on U.S. products going in, we will likewise drop ours. Big Deficit. If not, we Tax Cars etc. FAIR!"

But will this tactic work. Take the case of an automobile. A Volkswagen Beetle can be assembled in Mexico and exported to the European Union with no import tax. But if that same car were sent to Europe after being manufactured at a VW plant in Tennessee, the EU would impose an import tariff of 10 per cent. Trump is suggesting that the U.S. would raise its tax on imports of a BMW assembled in Germany to the European 10 per cent tariff unless the EU unilaterally lowered its auto tariffs to U.S. levels of 2.5 percent. However, imposing a 10 per cent tariffs on imports of German-assembled BMWs would do nothing for American-based automakers seeking sales in Europe unless the EU lowered its tariffs to zero on American arrivals.