On this day on 8th February

In March 1586, Anthony Babington and six friends gathered in The Plough, an inn outside Temple Bar, where they discussed the possibility of freeing Mary, assassinating Elizabeth, and inciting a rebellion supported by an invasion from abroad. With his spy network, it was not long before Walsingham discovered the existence of the Babington Plot. To make sure he obtained a conviction he arranged for Gifford to visit Babington on 6th July. Gifford told Babington that he had heard about the plot from Thomas Morgan in France and was willing to arrange for him to send messages to Mary via his brewer friend.

However, Babington did not fully trust Gifford and enciphered his letter. Babington used a very complex cipher that consisted of 23 symbols that were to be substituted for the letters of the alphabet (excluding j. v and w), along with 35 symbols representing words or phrases. In addition, there were four nulls and a symbol which signified that the next symbol represents a double letter. It would seem that the French Embassy had already arranged for Mary to receive a copy of the necessary codebook.

Gilbert Gifford took the sealed letter to Francis Walsingham. He employed counterfeiters, who would then break the seal on the letter, make a copy, and then reseal the original letter with an identical stamp before handing it back to Gifford. The apparently untouched letter could then be delivered to Mary or her correspondents, who remained oblivious to what was going on.

The copy was then taken to Thomas Phelippes. The copy was then taken to Thomas Phelippes. "In the ciphers used by Mary and her correspondents the letters of each word were encrypted using a system of substitutes or symbols which required for their decoding the construction of a parallel alphabet of letters. To establish such cipher keys Phelippes employed frequency analysis in which individual letters were identified in the order of those most commonly used in English and the less frequent substitutes deduced in the manner of a modern crossword puzzle." Eventually he was able to break the code used by Babington. The message clearly proposed the assassination of Elizabeth.

Walsingham now had the information needed to arrest Babington. However, his main target was Mary and he therefore allowed the conspiracy to continue. On 17th July she replied to Babington. The message was passed to Phelippes. As he had already broken the code he had little difficulty in translating the message that gave her approval to the assassination of Elizabeth. Mary Queen of Scots wrote: "When all is ready, the six gentlemen must be set to work, and you will provide that on their design being accomplished, I may be myself rescued from this place."

Walsingham now had enough evidence to arrest Mary and Babington. However, to destroy the conspiracy completely, he needed the names of all those involved. He ordered Phelippes to forge a postscript to Mary's letter, which would entice Babington to name the other men involved in the plot. "I would be glad to know the names and qualities of the six gentleman which are to accomplish the designment; for it may be that I shall be able, upon knowledge of the parties, to give you some further advice necessary to be followed therein, as also from time to time particularly how you proceed."

Simon Singh, the author of The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes & Code-Breaking (2000) has pointed out: "The cipher of Mary Queen of Scots clearly demonstrates that a weak encryption can be worse than no encryption at all. Both Mary and Babington wrote explicitly about their intentions because they believed that their communications were secure, whereas if they had been communicating openly they would have referred to their plan in a more discreet manner. Furthermore, their faith in their cipher made them particularly vulnerable to accepting Phelippes's forgery. Sender and receiver often have such confidence in the strength of their cipher that they consider it impossible for the enemy to mimic the cipher and insert forged text. The correct use of a strong cipher is a clear boon to sender and receiver, but the misuse of a weak cipher can generate a very false sense of security."

Francis Walsingham allowed the letters to continue to be sent because he wanted to discover who else was involved in this plot to overthrow Elizabeth. Eventually, on 25th June 1586, Mary wrote a letter to Anthony Babington. In his reply, Babington told Mary that he and a group of six friends were planning to murder Elizabeth. Babington discovered that Walsingham was aware of the plot and went into hiding. He hid with some companions in St John's Wood, but was eventually caught at the house of the Jerome Bellamy family in Harrow. On hearing the news of his arrest the government of the city put on a show of public loyalty, witnessing "her public joy by ringing of bells, making of bonfires, and singing of psalms".

Babington home was searched for documents that would provide evidence against him. When interviewed, Babington, who was not tortured, made a confession in which he admitted that Mary had written a letter supporting the plot. At his trial, Babington and his twelve confederates were found guilty and sentenced to hanging and quartering. "The horrors of semi-strangulation and of being split open alive for the heart and intestines to be wrenched out were regarded, like those of being burned to death, as awful but in the accepted order of things."

Gallows were set up near St Giles-in-the-Field and the first seven conspirators, led by Babington, were executed on 20th September 1586. Babington's last words were “Spare me Lord Jesus”. Another conspirator, Chidiock Tichborne, made a long speech where he blamed Babington "for drawing him in". The men "were hanged only for a short time, cut down while they were still alive, and then castrated and disembowelled".

The other seven were brought to the scaffold the next day and suffered the same death, "but, more favourably, by the Queens commandment, who detested the former cruelty" They hung until they were dead and only then suffered the barbarity of castration and disembowelling. The last to suffer was Jerome Bellamy, who was found guilty of hiding Babington and the others at his family's house in Harrow. His brother cheated the hangman by killing himself in prison.

Mary's trial took place at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire on 14th October 1586. A commission of thirty-four, consisting of councillors, peers and judges, was convened. She was charged with being an accessory to the attempted murder of Elizabeth. At first she refused to attend the trial unless it were understood that she did so, not as a criminal and not as one subject to English jurisdiction. Elizabeth was furious and wrote to Mary stating: "You have in various ways and manners attempted to take my life and to bring my kingdom to destruction by bloodshed.... These treasons will be proved to you and all made manifest. It is my will that you answer the nobles and peers of the kingdom as if I were myself present... Act plainly without reserve and you will the sooner be able to obtain favour of me."

During the trial Mary Stuart accused Walsingham of engineering her destruction by falsifying evidence. He rose to his feet and denied this: "I call God to witness that as a private person I have done nothing unbeseeming an honest man, nor, as I bear the place of a public man, have I done anything unworthy of my place. I confess that being very careful for the safety of the queen and the realm, I have curiously searched out all the practices against the same."

Julian Goodare has argued that the plot was a frame-up: "A channel of communication with Mary was arranged, with packets of coded letters hidden in beer barrels; unknown to the plotters, Walsingham saw all Mary's correspondence. The plot was thus a frame-up, a point of which Mary's defenders sometimes complain. It is not, however, obvious that the English government was obliged to nip the plot in the bud to prevent Mary from incriminating herself. The frame-up was directed almost as much against Elizabeth as against Mary."

The trial was moved to Westminster Palace on 25th October, where the 42-man commission, including Walsingham, found Mary guilty of plotting Elizabeth's assassination. As Walsingham had expected, Elizabeth proved reluctant to execute her rival and prevented a public verdict being decided after the trial. Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has argued that Elizabeth feared that Mary's execution might precipitate the rebellion or invasion which everybody feared. "To kill Mary was also foreign to Elizabeth's accustomed clemency and to her native fear of drastic action."

Parliament petitioned for Mary's execution. Elizabeth hesitated and as always she hoped to shift the responsibility for action on to others and "hinted that Mary's murder would not be displeasing to her". However, her government ministers refused to take action until he had written instructions from Elizabeth. On 19th December 1586, Mary wrote a long letter to Elizabeth arguing that she had been unjustly condemned by those who had no jurisdiction over her, and that she had "a constant resolution to suffer death for upholding the obedience and authority of the apostolical Roman church."

Parliament devised two bills: one to execute Mary for high treason, the other to say she was incapable of succession to the English throne. The first of these she rejected and the second she promised to consider. William Cecil told Walsingham that the House of Commons and the House of Lords were both determined on the only sensible course "but in the highest person, such slowness... such stay in resolution." Elizabeth stated to Walsingham and Cecil "Can I put to death the bird that, to escape the pursuit of the hawk, has fled to my feet for protection? Honour and conscience forbid!"

Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) has pointed out that she had ordered no execution by beheading since that of Thomas Howard, the 4th Duke of Norfolk, in 1572: "Since she came to the throne, Elizabeth had ordered no execution by beheading. After fourteen years of disuse, the scaffold on Tower Hill was falling to pieces, and it was necessary to put up another. The Duke's letters to his children, his letters to the Queen, his perfect dignity and courage at his death, made his end moving in the extreme, and he could at least be said that no sovereign had ever put a subject to death after more leniency or with greater unwillingness."

On 1st February 1587, Elizabeth finally signed the long-prepared warrant authorizing Mary's execution. She gave it to William Davison, Walsingham's recently appointed colleague as principal secretary, with vague and contradictory instructions. She also told Davison to get Walsingham to write to Amyas Paulet asking him to assassinate Mary. Paulet replied that he would not "make so foul shipwreck of his conscience as to shed blood without law or warrant". However, it has been argued that Paulet refused, either on principle or fearing that an assassin would become a scapegoat. "The episode reveals much about Elizabeth: most relevantly, it shows that she was no longer aiming to keep Mary alive, merely to preserve her own reputation. Elizabeth was genuinely distraught by the execution; her claim that it had been against her wishes was not strictly true, but may be understandable when it is recalled how long and how hard she had resisted the pressure for it."

Davidson took the execution warrant and on 3rd February, he convened a meeting of the leading councillors. William Cecil urged its immediate implementation without further reference to the queen. However, on 5th February she called in Davidson. According to Davidson, smiling, she told him she had dreamed the night before that Mary Stuart was executed, and this had put her "into such a passion with him". Davidson asked her if she still wanted to warrant to be executed. "Yes, by God," she answered, she did mean it, but she thought it should have been managed so that the whole responsibility did not fall upon herself.

Mary was informed on the evening of 7th February that she was to be executed the following day. She reacted by claiming that she was being condemned for her religion. She mounted the scaffold in the great hall of Fotheringhay, attended by two of her women servants, Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curle. The two executioners knelt before her and asked forgiveness. She replied, "I forgive you with all my heart, for now, I hope, you shall make an end of all my troubles."

Mary's last words were "Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit". The first blow missed her neck and struck the back of her head. The second blow severed the neck, except for a small bit of sinew, which the executioner cut through using the axe. He held her head aloft by the hair and declared, "God save the Queen." As he did so the head fell to the ground, revealing that Mary had been wearing a wig had actually had a very short, grey hair.

According to the account written by Robert Wynkfield: "Then one of the executioners, pulling off her garters, espied her little dog which was crept under her cloths, which could not be gotten forth by force, yet afterward would not depart from the dead corpse, but came and lay between her head and her shoulders, which being imbrued with her blood was carried away and washed, as all things else were that had any blood was either burned or washed clean, and the executioners sent away with money for their fees, not having any one thing that belonged unto her. And so, every man being commanded out of the hall, except the sheriff and his men, she was carried by them up into a great chamber lying ready for the surgeons to embalm her."

On this day in 1822 Richard Carlile publishes an article in The Republican demanding votes for women. It has been argued that the significance of Carlile's achievement lies in his contribution to the cause of free speech and a free press. "His publishing career and his championship of the oppressed, of no advantage to himself or his family, stand as testimony to the depth of commitment to be found in the artisan class of the early nineteenth century. Carlile never gave up, never became disaffected, and continuously sought to discover new opportunities of disseminating his conviction that freedom from the shackles of orthodoxy and oppression was essential for the future of his civilization".

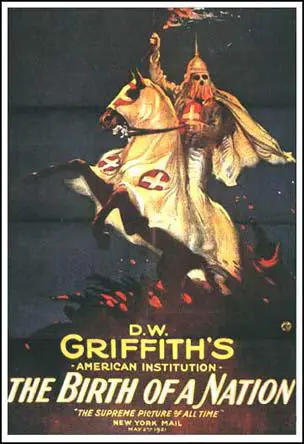

On this day in 1915 D.W. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation premieres in Los Angeles. Griffith, working in Hollywood, made over 400 films for the Biograph Company between 1907 and 1913. Griffith wanted to make feature-length films but when this idea was rejected he left the company. He immediately began work on adapting The Clansman, the novel by Thomas Dixon.

Dixon's novel tells the story of the aftermath of the American Civil War. Griffith, the son of a Confederate Colonel in the war, was interested in conveying the feelings of people living in the South after being defeated by the Northern army.

The Birth of a Nation created a sensation. Griffith's use of intricate editing and film techniques such as alternating close-ups and long-shots from varying camera angles, were revolutionary and inspired a generation of directors.

However, the film's portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan and African Americans, resulted in D.W. Griffith being accused of racism. Despite attempts by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to have the film banned, it was highly successful at the box office. The film, which cost $110,000 to make, eventually grossed more than $60 million.

Deeply hurt by the accusations of racism, Griffith's next film, Intolerance (1916), was a quartet of stories of man's inhumanity to man. Griffith's attempt to compensate for the politics of the Birth of a Nation was a commercial flop. The film left him heavily in debt and over the next few years desperately attempted to make films that would enable him to pay off his creditors.

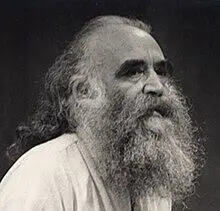

On this day in 1917, Igal Roodenko, the son of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine, was born on the 8th February, 1917. His father owned a small retail shop in New York City. Roodenko was raised as a Zionist and a socialist. He later recalled that at home he was taught "all the good values - humanist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist... the word socialist was a holy word to us."

Roodenko studied horticulture at Cornell University (1934-1938) with the intention of taking these skills to Palestine. He was radicalized at university and joined League for Industrial Democracy and the American Student Union. However, at university he became a pacifist and decided to stay in the United States: "aware of the conflict between my pacifism and my Zionism, and then ceased being a nationalist."

During the early stages of the Second World War Roodenko organized anti-war demonstrations. As Anne Yoder has pointed out: "Roodenko... circulated petitions, and wrote letters to Congressmen and newspaper editors urging their support of world peace. Roodenko's arguments were already incisive, showing the ability to cut through rhetoric to the root of a problem, and presented in a powerful style that not only highlighted his firm commitment to his beliefs but his ability to move others to action."

In 1942 he registered his conscientious objection to war and refused to accept being drafted into the military. In July 1943, he joined the Bureau of Land Reclamation of the Department of the Interior. Along with other pacifists he helped to erect an earth dam at the head of the Mancos River to irrigate Mancos Valley.

On 29th September, 1943, six war objectors imprisoned at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, started a hunger strike against censorship of mail and reading material by prison authorities. The following month Roodenko began his own hunger and work strike in support of these men: "My concern was with... censorship which occasionally reached preposterous depths of pettiness and stupidity, censorship of mail and reading matter which frequently denied men the opportunity of reading and writing about those very matters which made them sacrifice comforts and respect for the ignominy and disrepute of a prison record."

Roodenko was arrested for his refusal to work and on 6th June, 1944 a Denver judge found Roodenko guilty and sentenced him to three years in a federal penitentiary. He was released from Sandstone Federal Correctional Institution in Minnesota in December 1946.

On his release he joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Although Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) was against this kind of direct action, he volunteered the service of its southern attorneys during the campaign. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against the Journey of Reconciliation and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included Igal Roodenko, George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

James Peck was arrested with Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson in Durham. After being released he was arrested once again in Asheville and charged with breaking local Jim Crow laws. In Chapel Hill five members of the team was dragged off the bus and physically assaulted before being taken into custody by the local police.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave George Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

Roodenko was an active member of the War Resisters League (WRL) and was a member of its Executive Committee for thirty years. During the Vietnam War he was arrested ten times while taking part in anti-war protests. In 1970 he became a full-time worker for WRL. He was also active in Men of All Colors Together, a gay men's group working against racism within the gay community.

Igal Roodenko died of a heart attack on 28th April, 1991.

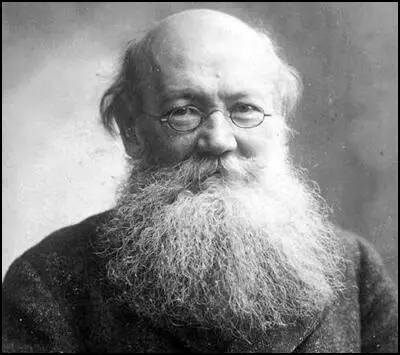

On this day in 1921 Peter Kropotkin died. Peter Alekseevich Kropotkin, the son of Aleksei Petrovich Kropotkin and Yekaterina Nikolaevna Sulima, was born in Moscow, Russia, on 12th December, 1842. The family was fairly wealthy and came from a noble lineage (Peter was in fact a prince).

Peter's mother died of tuberculosis in 1846. Two years later his father married Yelizaveta Mar'kovna Korandino. According to one source: "Yelizaveta caused a great deal of tension in the house. An aggressive, domineering woman, she attempted to erase all traces of the children's departed mother rather than offering them comfort. These actions caused further resentment between the children and their father."

His brother Nikolai (born in 1834) left the family home for military service in the Crimean War. His other brother, Alexander Kropotkin (born in 1841) also left home to join the Moscow Cadet Corps. Peter and Alexander had spent a great deal of their early lives together and were very close. Peter went to study at the First Moscow Gymnasium. He was not terribly impressed with the school, feeling that "all the subjects were taught in the most senseless manner." However, while at school, he did develop a strong interest in history and geography. At the age of 15 Kropotkin entered the aristocratic Corps des Pages of St. Petersburg and four years later became personal page to Tsar Alexander II.

Kropotkin first became aware of political censorship in Russia when his older brother, Alexander, was arrested in 1858 while a student at St. Petersburg University as a result of having a copy of a book, Self-Reliance, by Ralph Waldo Emerson. The book had been lent to him by one of the faculty, Professor Tikhonravof, but he refused to tell the police this because he did not want to get into trouble with the authorities. When Tikhonravof heard of Kropotkin's arrest he went at once to the rector of the university, and admitted that he was the owner of the book, and the young student was released.

In 1862 he applied for a commission in the Cossack Regiment serving in Eastern Siberia. After reading the work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the exploits of Mikhail Bakunin he developed an interest in anarchism. Kropotkin took a growing interest in politics. As Paul Avrich points out: "In Siberia he shed his hopes that the state could act as a vehicle of social progress. Soon after his arrival, he drafted, at the request of his superiors, elaborate plans for municipal self-government and for the reform of the penal system (a subject that was to interest him for the rest of his life), only to see them vanish in an impenetrable bureaucratic maze."

Disillusioned by the limits of these reforms, he undertook a geographical exploration in East Siberia and produced a paper on his theory of mountain structure. Kropotkin's reports on the topography of Siberia won him immediate recognition and in 1871 he was offered the coveted post of secretary of the Imperial Geographical Society in St. Petersburg. However, he rejected the post because of his new political commitment. "Although I did not then formulate my observations in terms borrowed from party struggles, I may say now that I lost in Siberia whatever faith in state discipline I had cherished before. I was prepared to become an anarchist."

In 1872 Peter Kropotkin joined a group that was spreading revolutionary propaganda among the workers and peasants of Moscow and St. Petersburg. He joined the Chaikovskii Circle, a group committed to disseminating propaganda among workers and peasants in order to prepare the way for a social revolution. They also published the work of writers such as Karl Marx, Alexander Herzen, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Peter Lavrov, John Stuart Mill and Charles Darwin.

In March 1874 he was arrested by the police. His house was searched and they found copies of a revolutionary manifesto that had been written by Kropotkin. They also found his diary and several books that had been banned by the authorities. Although they found plenty of incriminating evidence, the police had to bribe several witnesses to get a conviction. Kropotkin was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress but in 1876 he was able to escape and fled to Switzerland.

In 1876 his brother, Alexander Kropotkin, was arrested and charged with "political untrustworthiness" He was exiled to Minusinsk in Siberia, more than 3,000 miles from St. Petersburg and about 150 miles from the boundary line of Mongolia. His wife and children accompanied him into exile. He later told George Kennan that he thought he was being punished because of the political activities of his brother, Peter Kropotkin, who had been imprisoned two years earlier for being a member of the Chaikovskii Circle: "I am not a nihilist nor a revolutionist and I never have been. I was exiled simply because I dared to think, and to say - what I thought, about the things that happened around me, and because I was the brother of a man whom the Russian Government hated."

After the assassination of Tsar Alexander II his radical socialist views made him unwelcome in the country and in 1881 he moved to France where he became a member of the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a federation of radical political parties that hoped to overthrow capitalism and create a socialist commonwealth.

Peter Kropotkin continued to be interested in the work of Charles Darwin. He had profound respect for Darwin's discoveries and regarded the theory of natural selection as "perhaps the most brilliant scientific generalization of the century". Kropotkin accepted that the "struggle for existence" played an important role in the evolution of species. He argued that "life is struggle; and in that struggle the fittest survive". However, Kropotkin rejected the ideas of Thomas Huxley who placed great emphasis on competition and conflict in the evolutionary process.

In 1880 Kropotkin read an article by Karl Kessler, a Russian zoologist, entitled On the Law of Mutual Aid. Kessler's argued that cooperation rather than conflict was the chief factor in the process of evolution. He pointed out "the more individuals keep together, the more they mutually support each other, and the more are the chances of the species for surviving, as well as for making further progress in its intellectual development." Kessler died the following year and Kropotkin decided to spend time developing his theories.

Kropotkin published An Appeal to the Young in 1880. Anna Strunsky wrote that "hundreds of thousands had read that pamphlet and had responded to it as to nothing else in the literature of revolutionary socialism". Elizabeth Gurley Flynn later claimed that the message "struck home to me personally, as if he were speaking to us there in our shabby poverty-stricken Bronx flat."

In 1883 Kropotkin was arrested by the French authorities. He tried at Lyon, and sentenced, under a special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune, to five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the International Working Men's Association. While in prison Kropotkin's first ideas on anarchism were published. He was eventually released in 1886 and moved to England. Over the next few years he lived in Harrow, Acton, Ealing, Bromley and Highgate.

While living in England he became friends with other socialists, including William Morris, Keir Hardie, James Mavor, Tom Mann and George Bernard Shaw. Hardie once commented that if we were all like Kropotkin "anarchism would be the only possible system, since government and restraint would be unnecessary". In 1886 Kropotkin and his socialist friends organized a mass rally in London protesting against the death sentences imposed on the conviction of Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, George Engel, Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab for the Haymarket Bombing.

In 1886 he helped to establish the anarchist journal, Freedom. As anarchism's most important philosophers he was in great demand as a writer and contributed to the journals edited by Benjamin Tucker (Liberty), Albert Parsons (Alarm) and Johann Most (Freiheit). Tucker praised Kropotkin's publication as "the most scholarly anarchist journal in existence."

The following year he published In Russian and French Prisons. He argued that prisons are "schools of crime" and that by "subjecting him to brutalizing punishments, teaching him to lie and cheat, and generally hardening him in his criminal ways, so that when he emerges from behind bars he is condemned to repeat his transgressions.... Prisons neither improve the prisoners nor prevent crime; they achieve none of the ends for which they are designed."

Peter Kropotkin continued to develop his ideas on evolution. In 1888 Thomas Huxley published an article entitled The Struggle for Existence. He completely rejected Huxley's argument that competition among individuals of the same species is not merely a law of nature but the driving force of progress. Kropotkin replied to Huxley in a series of articles where he documented his theory of mutual aid with illustrations from animal and human life. Paul Avrich has argued: "Among animals he shows how mutual cooperation is practiced in hunting, in migration, and in the propagation of species. He draws examples from the elaborate social behavior of ants and bees, from wild horses that form a ring when attacked by wolves, from the wolves themselves that form a pack for hunting, from migrating deer that, scattered over a wide territory, come together in herds to cross a river. From these and many similar illustrations Kropotkin demonstrates that sociability is a prevalent feature at every level of the animal world. Moreover, he finds that among humans too mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. With a wealth of data he traces the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations that have continued to practice Mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. His thesis, in short, is a refutation of the doctrine that competition and brute force are the sole - or even the principal - determinants of social progress."

Alexander Kropotkin committed suicide on 25th July, 1890. The St Petersburg Eastern Review reported: "On the 25th of July, about nine o'clock in the evening, Prince A. A. Kropotkin committed suicide in Tomsk by shooting himself with a revolver. He had been in administrative exile about ten years, and his term of banishment would have expired on the 9th of next September. He had begun to make arrangements for returning to Russia, and had already sent his wife and his three children back to his relatives in the province of Kharkof. He was devotedly attached to them, and soon after their departure he grew lonely and low-spirited, and showed that he felt very deeply his separation from them. To this reason for despondency must also be added anxiety with regard to the means of subsistence. Although, at one time, a rather wealthy landed proprietor, Prince Kropotkin, during his long period of exile in Siberia, had expended almost his whole fortune; so that on the day of his death his entire property did not amount to three hundred rubles. At the age of forty-five, therefore, he was compelled, for the first time, seriously to consider the question how lie should live and support his family - a question which was the more difficult to answer for the reason that a scientific man, in Russia, cannot count upon earning a great deal in the field of literature, and Prince Kropotkin was not fitted for anything else. While under the disheartening influence of these considerations he received, moreover, several telegrams from his relatives which he misinterpreted. Whether he committed suicide as a result of sane deliberation, or whether a combination of circumstances super induced acute mental disorder, none who were near him at the moment of his death can say."

In 1892 Kropotkin published Conquest of Bread. It is generally agreed that the book is Kropotkin's clearest statement of his anarchist social doctrines. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "Written for the ordinary worker, it possesses a lucidity of style not often found in books on social themes." Emile Zola said that it was so well-written that it was a "true poem".

Kropotkin argued that the wage system, which presumes to measure the work of each individual in capitalism, must be abolished in favour of a system of equal rewards for all. Kropotkin suggested a system of "anarchist communism" by which private property and inequality of income would give place to the free distribution of goods and services. The author of Anarchist Portraits (1995) argued: "It was impossible to assess each person's contribution to the production of social wealth because millions of human beings had toiled to create the present riches of the world. Every acre of soil had been watered with the sweat of generations, every mile of railroad had received its share of human blood. Indeed, there was not a thought or an invention that was not the common inheritance of all mankind... Starting from this premise, Kropotkin argues that the wage system, which presumes to measure the work of each individual, must be abolished in favor of a system of equal rewards for all. This was a major step in the evolution of anarchist economic thought."

In Conquest of Bread Kropotkin argued that in an anarchist society no one would be compelled to work. He insisted that work is "a psychological necessity, a necessity of spending accumulated body energy, a necessity which is health and life itself. If so many) branches of useful work are reluctantly done now, it is merely because they mean overwork or they are improperly organized."

Kropotkin was also highly critical of the education system which he described as a "university of laziness". He argued that it was: "Superficiality, parrot-like repetition, slavishness and inertia of mind are the results of our method of education. We do not teach our children to learn." Kropotkin was one of the first to argue for "an active outdoor education and learn by doing and observing at first hand".

Kropotkin insisted that the education system would have to be completely reformed in order to create an anarchist society. "We are so perverted by an education which from infancy seeks to kill in us the spirit of revolt, and to develop that of submission to authority; we are so perverted by this existence under the ferrule of a law, which regulates every event in life - our birth, our education, our development, our love, our friendship - that, if this state of things continues, we shall lose all initiative, all habit of thinking for ourselves. Our society seems no longer able to understand that it is possible to exist otherwise than under the reign of law, elaborated by a representative government and administered by a handful of rulers.... The education we all receive from the State, at school and after, has so warped our minds that the very notion of freedom ends up by being lost, and disguised in servitude."

Kropotkin rejected the idea of a secret revolutionary party that had been suggested by Mikhail Bakunin. He also criticized the views of Sergi Nechayev. He insisted that social emancipation must be attained by libertarian rather than dictatorial means. Kropotkin rejected the idea of revolution put forward by Bakunin and Nechayev in Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869): "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it." For Kropotkin the ends and the means were inseparable.

In 1897 his old friend, James Mavor, professor of political economy at the University of Toronto, invited him to speak at a conference in Canada. He was impressed by the agricultural abundance throughout the country and wrote to a friend: "How rich mankind could be if social obstacles did not stand everywhere in the way of utilising the gifts of nature."

In October 1897, Kropotkin crossed the border into the United States to meet fellow anarchist, Johann Most. Although they had disagreed in the past about politics, Kropotkin argued that "with a few more Mosts, our movement would be much stronger". Writing in the Freiheit Most described Kropotkin as the "celebrated philosopher of modern anarchism" and that it had been a pleasure "to look into his eyes and shake his hand".

At Jersey City he was asked by a group of journalists for a statement on his political beliefs: "I am an anarchist and am trying to work out the ideal society, which I believe will be communistic in economics, but will leave full and free scope for the development of the individual. As to its organization, I believe in the formation of federated groups for production and consumption.... The social democrats are endeavoring to attain the same end, but the difference is that they start from the centre - the State and work toward the circumference, while we endeavor to work out the ideal society from the simple elements to the complex."

The New York Herald reported: "Prince Kropotkin is anything but the typical anarchist. In appearance he is patriarchal, and while his dress is careless it is the carelessness of the man who is engrossed in science rather than that of the man who is in revolt against the usages of society. His manners are those of the polished gentleman, and he has none of the bitterness and dogmatism of the anarchist whom we are accustomed to see here."

In New York City Kropotkin spoke at a meeting chaired by John Swinton on the dangers of state socialism. One member of the audience later recorded that he "wore a patriarchal beard and beamed on his audience from behind a pair of spectacles like an old fashioned clergyman looking over a familiar congregation." Another remarked that "his evident sincerity and his kindness held the attention of his audience and gained its sympathy".

In 1899 Kropotkin visited Chicago and lived in the Hull House settlement, formed by Jane Addams, for a while. Alice Hamilton, one of the workers at the settlement, later recalled: "Prince Peter Kropotkin was one of the most lovable persons I have ever met. He was a typical revolutionist of the early Russian type, an aristocrat who threw himself into the movement for emancipation of the masses out of a passionate love for his fellow man, and a longing for justice. He stayed some time with us at Hull House, and we all came to love him, not only we who lived under the same roof but the crowds of Russian refugees who came to see him. No matter how down-and-out, how squalid even, a caller would be., Prince Kropotkin would give him a joyful welcome and kiss him on both cheeks."

Robert Lovett admitted that: "Hull House was emphatically the refuge of lost causes. The anarchist agitation had died out, but the fear of it was maintained by press and police to haunt the slumbers of the best people. Miss Addams was attacked for entertaining Peter Kropotkin in Hull House. The celebration of his birthday was an occasion for the visit to Chicago to the mild ghost of anarchism." Given this hostility Kropotkin decided to return to London.

In his final years Kropotkin concentrated on writing. His works during this period he produced an autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionist (1899), Fields, Factories and Workshops (1901), Mutual Aid (1902) and The Great French Revolution (1909) turned him into a world known political figure. Emma Goldman argued: "We saw in him the father of modern anarchism, its revolutionary spokesman and brilliant exponent of its relation to science, philosophy and progressive thought." and was described by Emma Goldman as the "godfather of anarchism".

In 1912 Kropotkin moved to Brighton where he stayed for the next five years. After the overthrow of the Tsar Nicholas II in 1917, Kropotkin returned home to Russia expecting the development of "anarchist communism". When the Bolsheviks seized power he remarked to a friend that "this buries the revolution" and described government members as "state socialists".

In June 1918, Peter Kropotkin had a meeting with Nestor Makhno, the leader of the anarchists in the Ukraine. He told him about a conversation he had with Lenin in the Kremlin. Lenin explained his opposition to anarchists. "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them... But I think that you, comrade, have a realistic attitude towards the burning evils of the time. If only one-third of the anarchist-communists were like you, we Communists would be ready, under certain well-known conditions, to join with them in working towards a free organization of producers."

Kropotkin disliked the developments that took place over the next few months and in March 1920 he sent a letter to Lenin that claimed Russia was a "Soviet Republic only in name" and "at present it is not the soviets which rule in Russia but party committees".

Peter Kropotkin died of pneumonia in the city of Dmitrov on 8th February, 1921, and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. His friend, Victor Serge, attended the funeral. "These were heartbreaking days: the great frost in the midst of the great hunger. I was the only member of the party to be accepted as a comrade in anarchist circles. The shadow of the Cheka fell everywhere, but a packed and passionate multitude thronged around the bier, making this funeral ceremony into a demonstration of unmistakable significance." Kropotkin's final book, Ethics, Origin and Development (1922) was published posthumously.

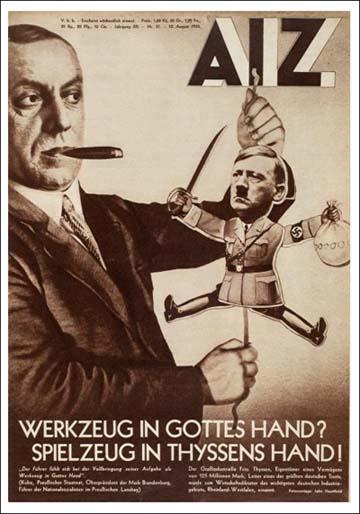

On this day in 1951 Fritz Thyssen, died. Thyssen, the son of the successful industrialist, August Thyssen (1842-1926), was born on the 9th November, 1873. He joined the German Army in 1896 and reached the rank of second lieutenant.

In 1898 Thyssen joined Thyssen & Co a company owned by his father in the Ruhr. By the outbreak of the First World War the company employed 50,000 workers and produced 1,000,000 tons of steel and iron a year.

In 1923 took part in the resistance against the Ruhr Occupation by Belgian and French troops. He was arrested and received a large fine for his activities.

At a meeting with General Eric Ludendorff in October 1923, Thyssen was advised to go and hear Adolf Hitler speak. He did this and was so impressed he began to finance the Nazi Party.

Thyssen inherited his father's fortune in 1926. He continued to expand and in 1928 formed United Steelworks, a company that controlled more that 75 per cent of Germany's ore reserves and employed 200,000 people.

By 1930 Thyssen was one of the leading backers of the Nazi Party. The following year he recruited Hjalmar Schacht to the cause and in November, 1932, the two men joined with other industrialists in signing the letter that urged Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Adolf Hitler as chancellor. This was successful and on 20th February, 1933, they arranged a meeting of the Association of German Industrialists that raised 3 million marks for the Nazi Party in the forthcoming election.

Thyssen supported the measures that Hitler took against the left-wing political groups and trade unions. He also put pressure on Hitler to suppress the left of the Nazi Party that resulted in the Night of the Long Knives. However, as a Catholic, Thyssen objected when Hitler began persecuting people for their religious beliefs.

Thyssen resigned as state councillor in protest against Crystal Night. The following year he fled to Switzerland and Hitler promptly confiscated his property. Thyssen moved to France but was arrested by the Vichy government and was returned to Germany where he was sent to a concentration camp.

Thyssen was freed by Allied forces in 1945. Arrested he was convicted by a German court for being a former leader of the Nazi Party and was ordered to hand over 15 per cent of his property to provide a victims of Nazi persecution.

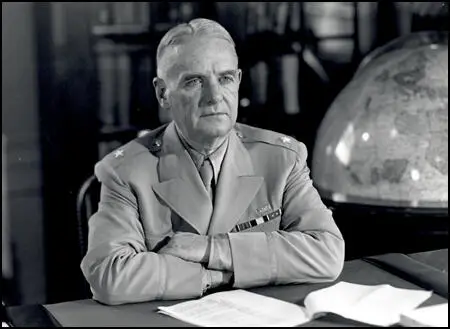

On this day in 1959 William J. Donovan, died. Donovan, the son of Timothy P. Donovan and Anna Lennon Donovan, was born in Buffalo, United States, on 1st January, 1883. He attended St. Joseph's Collegiate Institute and Niagara University before starring on the football team at Columbia University. It was his style of play that got him the nickname, "Wild Bill".

After graduating from Columbia Law School and became an influential Wall Street lawyer. In 1912, Donovan formed and led a troop of cavalry of the New York State Militia and served on the United States-Mexico border during the American government's campaign against Pancho Villa.

During the First World War Donovan organized and led the 1st battalion of the 165th Regiment of the 42nd Division. He served on the Western Front and in October, 1918 he received the Medal of Honor. The citation read: "Lt. Col. Donovan personally led the assaulting wave in an attack upon a very strongly organized position, and when our troops were suffering heavy casualties he encouraged all near him by his example, moving among his men in exposed positions, reorganizing decimated platoons, and accompanying them forward in attacks. When he was wounded in the leg by machine-gun bullets, he refused to be evacuated and continued with his unit until it withdrew to a less exposed position." By the end of the war he had been promoted to the rank of colonel. In 1919 he visited Russia and spent time with Alexander Kolchak and the White Army.

William J. Donovan was an active member of the Republican Party and after meeting Herbert Hoover he worked as his political adviser, speech writer and campaign manager. Donovan ran unsuccessfully as lieutenant governor in 1922 but was appointed by President Calvin Coolidge as his assistant attorney general. In 1928, Donovan had been acting attorney general in the Coolidge administration. When he became president in 1929, it was assumed that Hoover would appoint Donovan as attorney general. Hoover did not do so because, it was rumored, powerful Republicans did not want a Catholic in the cabinet.

By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president in 1932 Donovan was a millionaire Wall Street lawyer. He was a strong opponent of Roosevelt's New Deal but became a close advisor to the administration. Ernest Cuneo, who also worked for Roosevelt, claimed that Donovan was the leader of "Franklin's brain trust". It appears that Donovan shared the president's concern about political developments in Nazi Germany.

During the First World War Donovan became friends with William Stephenson. When Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940 he appointed Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC) that was based in New York City. Churchill told Stephenson: "You know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds between us. You are to be my personal representative in the United States. I will ensure that you have the full support of all the resources at my command. I know that you will have success, and the good Lord will guide your efforts as He will ours." Charles Howard Ellis said that he selected Stephenson because: "Firstly, he was Canadian. Secondly, he had very good American connections... he had a sort of fox terrier character, and if he undertook something, he would carry it through."

As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention." An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI.

In July, 1940, Roosevelt appointed Frank Knox as Secretary of the Navy. The two men discussed the possibility of appointing Donovan as Secretary of War. Knox told Roosevelt: "Frankly, if your proposal contemplated Donovan for the War Department and myself for the Navy, I think the appointments could be put solely upon the basis of a nonpartisan nonpolitical measure of putting our national defense departments in such a state of preparedness as to protect the United States against any danger to our security." Roosevelt replied "Bill Donovan is also an old friend of mine - we were in law school together and frankly, I should like to have him in the Cabinet, not only for his own ability, but also to repair in a sense the very great injustice done him by President Hoover in the winter of 1929."

Eventually, Roosevelt decided to appoint fellow Republican, Henry Stimson, as Secretary of War. Jean Edward Smith, the author of FDR (2008) has argued that Roosevelt was determined to get the timing of the decision right: "It was important to stress the bipartisan nature of the defense effort, he told Knox. Even more important, if the GOP nominated an isolationist candidate, Knox and Stimson would be deemed guilty of bad sportsmanship in joining FDR's team afterward." Knox was allowed to bring in James V. Forrestal, an investment banker, as his undersecretary.

In the summer of 1940 Winston Churchill had a serious problem. Joseph P. Kennedy was the United States Ambassador to Britain. He soon came to the conclusion that the island was a lost cause and he considered aid to Britain fruitless. Kennedy, an isolationist, consistently warned Roosevelt "against holding the bag in a war in which the Allies expect to be beaten." Neville Chamberlain wrote in his diary in July 1940: "Saw Joe Kennedy who says everyone in the USA thinks we shall be beaten before the end of the month." Averell Harriman later explained the thinking of Kennedy and other isolationists: "After World War I, there was a surge of isolationism, a feeling there was no reason for getting involved in another war... We made a mistake and there were a lot of debts owed by European countries. The country went isolationist.

William Stephenson later commented: "The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan." Donovan arranged meetings with Henry Stimson (Secretary of War), Cordell Hull (Secretary of State) and Frank Knox (Secretary of the Navy). The main topic was Britain's lack of destroyers and the possibility of finding a formula for transfer of fifty "over-age" destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality legislation.

It was decided to send Donovan and Edgar Ansel Mowrer to Britain on a fact-finding mission. They left on 14th July, 1940. When he heard the news, Joseph P. Kennedy complained: "Our staff, I think is getting all the information that possibility can be gathered, and to send a new man here at this time is to me the height of nonsense and a definite blow to good organization." He added that the trip would "simply result in causing confusion and misunderstanding on the part of the British". Andrew Lycett has argued: "Nothing was held back from the big American. British planners had decided to take him completely into their confidence and share their most prized military secrets in the hope that he would return home even more convinced of their resourcefulness and determination to win the war."

William J. Donovan arrived back in the United States in early August, 1940. In his report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt he argued: "(1) That the British would fight to the last ditch. (2) They could not hope to hold to hold the last ditch unless they got supplies at least from America. (3) That supplies were of no avail unless they were delivered to the fighting front - in short, that protecting the lines of communication was a sine qua non. (4) That Fifth Column activity was an important factor." Donovan also urged that the government should sack Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, who was predicting a German victory. Donovan also wrote a series of articles arguing that Nazi Germany posed a serious threat to the United States.

In July 1941, Roosevelt appointed Donovan as his Coordinator of Information. The following year Donovan became head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), an organization that was given the responsible for espionage and for helping the resistance movement in Europe. Donovan published a secret document where he outlined his objectives: "Espionage is not a nice thing, nor are the methods employed exemplary. Neither are demolition bombs nor poison gas, but our country is a nice thing and our independence is indispensable. We face an enemy who believes one of his chief weapons is that none but he will employ terror. But we will turn terror against him - or we will cease to exist."

Over the next few years William Stephenson worked closely with Donovan. Gill Bennett, the author of Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009), has argued: "Each is a figure about whom much myth has been woven, by themselves and others, and the full extent of their activities and contacts retains an element of mystery. Both were influential: Stephenson as head of British Security Coordination (BSC), the organisation he created in New York at Menzies's request and Donovan, working with Stephenson as intermediary between Roosevelt and Churchill, persuading the former to supply clandestine military supplies to the UK before the USA entered the war, and from June 1941 head of the COI and thus one of the architects of the US Intelligence establishment."

Ray S. Cline was one of Donovan's agents: "Wild Bill deserves his sobriquet mainly for two reasons. First, he permitted the wildest, loosest kind of administrative and procedural chaos to develop while he concentrated on recruiting talent wherever he could find it - in universities, businesses, law firms, in the armed services, at Georgetown cocktail parties, in fact, anywhere he happened to meet or hear about bright and eager men and women who wanted to help. His immediate lieutenants and their assistants were all at work on the same task, and it was a long time before any systematic method of structuring the polyglot staff complement was worked out. Donovan really did not care. He counted on some able young men from his law firm in New York to straighten out the worst administrative messes, arguing that the record would justify his agency if it was good and excuse all waste and confusion. If the agency was a failure, the United States would probably lose the war and the bookkeeping would not matter. In this approach he was probably right."

Donovan was given the rank of major general and during the war he built up a team of 16,000 agents working behind enemy lines. He later recalled: "Intelligence service that counts isn't the kind you read about in spy books. Women agents are less often the sultry blonde or the dazzling duchess than they are girls like the young American with an artificial leg who stayed on in France to operate a clandestine radio station; girls like the thirty-seven who worked for us in China, daughters of missionaries and of businessmen, who had grown up there. I hope that the story of the women in OSS will soon be written. Our men agents didn't fit the traditional types in spy stories any more than the women we used. Do you know that one of our most notable achievements was the extent to which we found we could use labor unions? Our informer in this war was less often a slick little man with a black moustache than a transport worker, a truck driver, or a freight train conductor."

Ray S. Cline admitted: "Donovan did manage during the war to create a legend about his work and that of OSS that conveyed overtones of glamour, innovation, and daring. This infuriated the regular bureaucrats but created a cult of romanticism about intelligence that persisted and helped win popular support for continuation of an intelligence organization." One of those who was "infuriated" with Donovan was John Edgar Hoover who saw the OSS as a rival to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Richard Deacon, the author of Spyclopaedia: The Comprehensive Handbook of Espionage (1987), has pointed out: "Hoover constantly worked against Donovan... and OSS activities had to be confined mainly to Europe and North Africa. Increasingly, towards the end of the war, Donovan felt that the Americans and the British were giving away too much intelligence to the Russians, and fearing that Russia would be the prime enemy afterwards, he pressed for the creation of a permanent Secret Service for the USA, based on the OSS."

As soon as the Second World War ended President Harry S. Truman ordered the OSS to be closed down. However, it provided a model for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) established in September 1947. Others have suggested that it was the British Security Coordination (BSC) that was really the important organisation. According to Joseph C. Goulden several of the "old boys" who were around for the founding of the CIA like repeating a mantra, “The Brits taught us everything we know - but by no means did they teach us everything that they know.”

William J. Donovan returned to his law practice but later set up the British-American-Canadian-Corporation (later called the World Commerce Corporation) with William Stephenson. It was a secret service front company which specialized in trading goods with developing countries. William Torbitt has claimed that it was "originally designed to fill the void left by the break-up of the big German cartels which Stephenson himself had done much to destroy."

William Donovan died at the age of 76 from complications of vascular dementia on 8th February, 1959, at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.