On this day on 1st April

On this day in 1578 William Harvey is born in Folkestone on 1st April 1578. After studying medicine at Caius College, Cambridge, he went to work at Padua.

In 1602 Harvey returned to London and began work as a doctor at St. Bartholomew's Hospital and in 1615 he was appointed Lumleian Lecturer at the College of Physicians.

Harvey became court physician to James I in 1618. Ten years later Harvey published On the Motion of the Heart and the Blood in Animals. In the book Harvey explained that after examining the heart and blood vessels of mammals he believed that the blood in the veins must flow only towards the heart. He also calculated the amount of blood that left the heart at each beat.

In 1640 Harvey became court physician to Charles II and was with the king during the Civil War and saw action at Edgehill.

During the Civil War Harvey continued his medical research and in 1651 published Essays on Generation in Animals. In the book he argued that every human being has its origin in an egg. William Harvey died on 3rd June 1657.

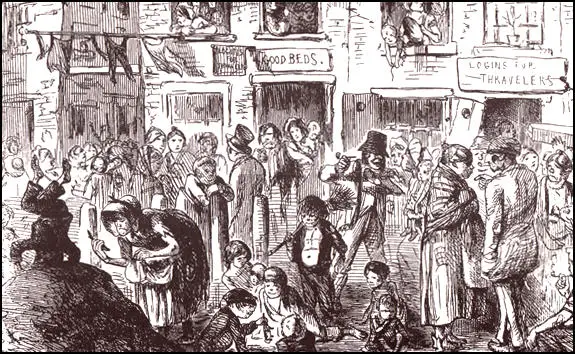

On this day in 1649, Gerald Winstanley, William Everard, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them.

The men sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". Research shows that new people joined the community over the next few months. Most of these were local inhabitants. These men became known as Diggers.

John Gurney has argued that "Everard's flamboyant character and his preference for confrontation over presentation helped to ensure that in the early days of the digging he was more quickly noticed than the more self-effacing Winstanley, and many observers assumed that it was he, rather than Winstanley, who was the real leader of the Diggers".

According to Peter Ackroyd, Everard proclaimed in a vision by God to "dig and plough the land" and that the Diggers believed in a form of "agrarian communism" and that that it was time for the English to free themselves from the the tyranny of Norman landlords and to make "the earth a common treasury for all."

Laurence Clarkson claimed that he had supported the ideas of Winstanley and had spent some time digging on the commons. However, Winstanley strongly disapproved of Clarkson's sexual ideas and condemned the "Ranting crew" and he warned fellow Diggers to steer clear of "lust of the flesh" and "the practise of Ranting".

Winstanley announced his intentions in a manifesto entitled The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649). It opened with the words: "In the beginning of time, the great Creator Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, to preserve Beasts, Birds, Fishes, and Man, the lord that was to govern this Creation; for Man had Domination given to him, over the Beasts, Birds, and Fishes; but not one word was spoken in the beginning, that one branch of mankind should rule over another."

Gerald Winstanley argued for a society without money or wages: "The earth is to be planted and the fruits reaped and carried into barns and storehouses by the assistance of every family. And if any man or family want corn or other provision, they may go to the storehouses and fetch without money. If they want a horse to ride, go into the fields in summer, or to the common stables in winter, and receive one from the keepers, and when your journey is performed, bring him where you had him, without money."

Digger groups also took over land in Kent (Cox Hill), Buckinghamshire (Iver) and Northamptonshire (Wellingborough). A. L. Morton has argued that Winstanley and his followers used the argument that William the Conqueror had "turned the English out of their birthrights; and compelled them for necessity to be servants to him and to his Norman soldiers." Winstanley responded to this situation by advocating what Morton describes as "primitive communism".

Winstanley's writings suggested that he shared the view held by the Anabaptists that all institutions were by their nature corrupt: "nature tells us that if water stands long it corrupts; whereas running water keeps sweet and is fit for common use". To prevent power corrupting individuals he advocated that all officials should be elected every year. "When public officers remain long in place of judicature they will degenerate from the bounds of humility, honesty and tender care of brethren, in regard the heart of man is so subject to be overspread with the clouds of covetousness, pride, vain glory."

Local landowners were very disturbed by these developments. According to one historian, John F. Harrison: "They were repeatedly attacked and beaten; their crops were uprooted, their tools destroyed, and their rough houses." Oliver Cromwell also condemned the actions of the Diggers: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces."

On 16th April 1649, Henry Saunders, a yeoman of the parish, complained to the council of state about the growing number of Diggers, now "between 20 and 30". A report was sent to General Thomas Fairfax, the commander of the army, stating that "although the pretence of their being there by them avowed may seem very ridiculous, yet that conflux of people may be a beginning whence things of a greater and more dangerous consequence may grow to this disturbance of the peace and quiet of the Commonwealth." It suggested that Fairfax should send some troops to disperse the Diggers and prevent them from returning to St George's Hill.

General Fairfax sent Captain John Gladman was sent to St George's Hill and found only four men digging. The camp had already been dealt with by local inhabitants: "They have digged in all about an acre of land, but it is trampled down by the country people, who would not suffer them to dig one day more."

On 20th April, Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, appeared before General Fairfax in London. Both men, because of their political beliefs, refused to remove their hats in the presence of the General. Everard told Fairfax that since the Norman Conquest, England had lived under a tyranny. He assured Fairfax that he and his fellows did not intend either to interfere with private property or to destroy enclosures, but that they were merely claiming the commons which were the rightful possession of the poor. The two men made it clear that they intended to cultivate the wastelands in common and to provide sustenance for the distressed."

Gerrard Winstanley wrote to General Fairfax in June 1649 explaining his objectives: "And the truth is, experience shows us, that in this work of Community in the earth, and in the fruits of the earth, is seen plainly a pitched battle between the Lamb and the Dragon, between the Spirit of love, humility and righteousness... and the power of envy, pride, and unrighteousness ... the latter power striving to hold the Creation under slavery, and to lock and hide the glory thereof from man: the former power labouring to deliver Creation from slavery, to unfold the secrets of it to the sons of man, and so to manifest himself to be the great restorer of all things."

Winstanley continued his experiment and on 1st June he published A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, that was signed by 44 people. It stated that while waiting for their first crop yields, they proposed to sell wood from the commons in order to buy food, ploughs, carts, and corn. No threat would be made to private property, but "the promises of reformation and liberation made from the solemn league and covenant through to the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords must be honoured".

Instructions were given for the Diggers to be beaten up and for their houses, crops and tools to be destroyed. These tactics were successful and within a year all the Digger communities in England had been wiped out. A number of Diggers were indicted at the Surrey quarter sessions and five were imprisoned for just over a month in the White Lion prison in Southwark.

Despite the hostility Winstanley's experiment continued and in January 1650 "having put my arm as far as my strength will go to advance righteousness: I have writ, I have acted, I have peace: and now I must wait to see the spirit do his own work in the hearts of others, and whether England shall be the first land, or some other, wherein truth shall sit down in triumph."

On 19th April, 1650, a group of local landowners, including John Platt, Thomas Sutton, William Starr and William Davy, with several hired men, destroyed the Digger community in Cobham: "They set fire to six houses, and burned them down, and burned likewise some of the household stuff... not pitying the cries of many little children, and their frightened mothers.... they kicked a poor man's wife, so that she miscarried her child."

Gerald Winstanley returned to farming his own land. The historian, Alfred Leslie Rowse, quoted one source that claimed he had made a "most shameful retreat from George's Hill, with a spirit of pretended universality, to become a real tithe-gather of propriety". Rowse harshly argues that "Winstanley was no better than the rest of the Saints - out of his own ends."

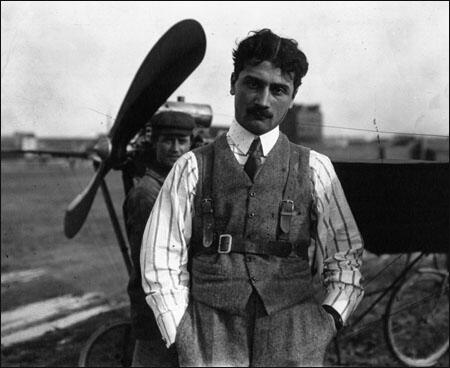

On this day in 1915 Roland Garros uses deflector plates for the first time. On the outbreak of the First World War, Garros was sent to serve on the Western Front. Garros realised that he would have more success in dogfights if he could find a way of firing a machine-gun through the propeller. Working with Raymond Saulnier, a French aircraft manufacturer, Garros, added deflector plates to the blades of the propeller of his Morane-Saulnier. These small wedges of toughened steel diverted the passage of those bullets which struck the blades.

Now able to use a forward-firing machine-gun, went out searching for his first victim. On 1st April 1915, Garros approached an German Albatros B II reconnaissance aircraft. The German pilot was surprised when Garros approached him head-on. The accepted air fighting strategy at the time was to take 'pot-shots' with a revolver or rifle. Instead Garros shot down the Albatros through his whirling propeller.

In the next two weeks Garros shot down four more enemy aircraft. However, the success was short-lived because on 18th April, a rifleman defending Courtrai railway station, managed to fracture the petrol pipe of the aircraft that Garros was flying. Garros was forced to land behind the German front-line and before he could set-fire to his machine it was captured by the Germans. After finding out about Garros' invention, German pilots began using these deflector plates on the blades of their propellers.

In 1918 Garros escaped from Germany and returned to active service on the Western Front. Roland Garros was shot down and killed at Vouziers on 5th October 1918.

On this day in 1832 Charles Greville writes in his diary about the cholera outbreak. "I have refrained for a long time from writing down anything about the cholera because the subject is intolerably disgusting to me, and I have been bored past endurance by the perpetual questions of every fool about it. It is not, however, devoid of interest. In the first place, what has happened here proves that the people of this enlightened, reading, thinking, reforming nation are not a whit less barbarous than the serfs in Russia, for precisely the same prejudices have been shown here that were found at St Petersburg and at Berlin. The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken."

Rioting broke out all over Britain. Crowds of men, women and children smashed windows at the Toxteth Park Cholera Hospital in Liverpool and pelted members of the local board of health with bricks. On 2nd September 1832, violence erupted in Manchester when a mob Swan Street Hospital, breaking down the gates and fighting a pitched battle with the police. This was as a result of a local man, John Hare, discovering that his grandson's body, who had died of cholera, had been smuggled out of the hospital by a doctor who wanted to dissect it.

On this day in 1877 Maurice Hankey, the third son and fifth child of Robert Alers Hankey (1838–1906), and his wife, Helen Bakewell (1845–1900), was born in Biarritz. His father, who was a sheep farmer in Australia, eventually moved the family to Brighton.

After being educated at Rugby School (1890-1895) he was commissioned in the Royal Marine Artillery in 1897. According to his biographer, John F. Naylor: "After specialized instruction at Eastney barracks, Portsmouth, he came first in all his examinations. In late 1898 he secured a choice subaltern appointment on the Ramillies, the flagship of the Mediterranean station, to which he soon added unofficial and unpaid intelligence work, an activity which he would maintain to the end of his public life and beyond." Hankey came to the attention of Admiral John Fisher, the Mediterranean commander and soon to be first sea lord. In April 1902 Hankey joined the staff of the naval intelligence department, his first Whitehall appointment.

Hankey was an extremely efficient intelligence officer and according to Stephen Roskill, the author of Hankey, Man of Secrets (1970) he was described as being "a walking encyclopaedia of defence matters". He was also a talented linguist and spoke French, Italian, German and Greek. He admitted to his wife, Adeline de Smidt (1882–1979), that his career would unfold "not as a fighting man but as a sound peace administrator".

In January 1908 Hankey returned to Whitehall as a member of the permanent subcommittee of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID). In theory, the CID functioned as the prime minister's department to oversee defence planning. In practice, however, it only advised on technical questions and could not contribute to the formulation of defence policies. In 1912 Hankey became secretary of CID.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Hankey became secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet. Hankey and his friend, Colonel Ernest Swinton, became convinced that it was necessary to developed an armoured vehicle to counteract the development of machine-guns. When Swinton's proposals were rejected by General Sir John French and his scientific advisers, Hankey took them to Winston Churchill, the navy minister. This action resulted in the development of the tank.

It has been suggested that Herbert Asquith and the CID was never able to get total control of the war effort. It has been argued by John F. Naylor: "Neither this flawed body - partly advisory, partly executive - nor its two successors, the Dardanelles committee (June - October 1915), and the war committee (November 1915 - November 1916) enabled the Asquith coalition to prevail over the military authorities in planning what remained an ineffective war effort."

At a meeting in Paris on 4th November, 1916, David Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lloyd George agreed with Hankey, that he should talk to Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, about the situation. Bonar Law remained loyal to Asquith and so Lloyd George contacted Max Aitken instead and told him about his suggested reforms.

On 18th November, Aitken lunched with Bonar Law and put Lloyd George's case for reform. He also put forward the arguments for Lloyd George becoming the leader of the coalition. Aitken later recalled in his book, Politicians and the War (1928): "Once he had taken up war as his metier he seemed to breathe its true spirit; all other thoughts and schemes were abandoned, and he lived for, thought of and talked of nothing but the war. Ruthless to inefficiency and muddle-headedness in his conduct, sometimes devious, if you like, in the means employed when indirect methods would serve him in his aim, he yet exhibited in his country's death-grapple a kind of splendid sincerity."

Together, David Lloyd George, Max Aitken, Andrew Bonar Law and Edward Carson, drafted a statement addressed to Asquith, proposing a war council triumvirate and the Prime Minister as overlord. On 25th November, Bonar Law took the proposal to Asquith, who agreed to think it over. The next day he rejected it. Further negotiations took place and on 2nd December Asquith agreed to the setting up of "a small War Committee to handle the day to day conduct of the war, with full powers", independent of the cabinet. This information was leaked to the press by Carson. On 4th December The Times used these details of the War Committee to make a strong attack on Asquith. The following day he resigned from office.

Lloyd George decided to establish what he described as "virtually a new system of government in this country". John F. Naylor has explained: "Hankey headed the operation - the secretary himself drew up the procedural rules - with these responsibilities, among others: (1) to record the proceedings of the War Cabinet; (2) to transmit relevant extracts from the minutes to departments concerned with implementing them or otherwise interested; (3) to prepare the agenda paper, and to arrange the attendance of ministers not in the War Cabinet and others required to be present for discussion of particular items on the agenda; (4) to receive papers from departments and circulate them to the War Cabinet or others as necessary. Thus Hankey established the precepts for a co-ordinating and record-keeping organization which the cabinet secretariat and its seamless successor, the Cabinet Office (from 1920), subsequently followed. The creation of the cabinet secretariat was his greatest achievement."

A.J.P. Taylor has argued in English History 1914-1945 (1965): "Where the old cabinet had met once a week or so and had kept no record of its proceedings, the war cabinet met practically every day - 300 times in 1917 - and Hankey, brought over from the Committee of Imperial Defence and its successors, organized an efficient secretariat. He prepared agenda; kept minutes; and ensured afterwards that the decisions were operated by the department concerned. Hankey was also tempted to exceed his functions and to initiate proposals, particularly on strategy, instead of merely recording decisions."

According to the historian, Michael Kettle, Hankey became involved in a plot to overthrow David Lloyd George. Others involved in the conspiracy included General William Robertson, Chief of Staff and the prime ministers main political adviser, Colonel Charles Repington, the military correspondent of the Morning Post and General Frederick Maurice, director of military operations at the War Office. Kettle argues that: "What Maurice had in mind was a small War Cabinet, dominated by Robertson, assisted by a brilliant British Ludendorff, and with a subservient Prime Minister. It is unclear who Maurice had in mind for this Ludendorff figure; but it is very clear that the intention was to get rid of Lloyd George - and quickly."

On 24th January, 1918, Repington wrote an article where he described what he called "the procrastination and cowardice of the Cabinet". Later that day Repington heard on good authority that Lloyd George had strongly urged the War Cabinet to imprison both him and his editor, Howell Arthur Gwynne. That evening Repington was invited to have dinner with Lord Chief Justice Charles Darling, where he received a polite judicial rebuke.

General William Robertson disagreed with Lloyd George's proposal to create an executive war board, chaired by Ferdinand Foch, with broad powers over allied reserves. Robertson expressed his opposition to General Herbert Plumer in a letter on 4th February, 1918: "It is impossible to have Chiefs of the General Staffs dealing with operations in all respects except reserves and to have people with no other responsibilities dealing with reserves and nothing else. In fact the decision is unsound, and neither do I see how it is to be worked either legally or constitutionally."

On 11th February, Repington, revealed in the Morning Post details of the coming offensive on the Western Front. Lloyd George later recorded: "The conspirators decided to publish the war plans of the Allies for the coming German offensive. Repington's betrayal might and ought to have decided the war." Repington and his editor, Howell Arthur Gwynne, were fined £100 each, plus costs, for a breach of Defence of the Realm regulations when he disclosed secret information in the newspaper.

General William Robertson wrote to Repington suggesting that he had been the one who had leaked him the information: "Like yourself, I did what I thought was best in the general interests of the country. I feel that your sacrifice has been great and that you have a difficult time in front of you. But the great thing is to keep on a straight course". General Frederick Maurice also sent a letter to Repington: "I have the greatest admiration for your courage and determination and am quite clear that you have been the victim of political persecution such as I did not think was possible in England."

Robertson put up a fight in the war cabinet against the proposed executive war board, but when it was clear that Lloyd George was unwilling to back down, he resigned his post. He was now replaced with General Henry Wilson. General Douglas Haig rejected the idea that Robertson should become one of his commanders in France and he was given the eastern command instead.

Maurice Hankey remained in power after the First World War. He was appointed as secretary of the cabinet (1919) and secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence (1920) and clerk of the privy council (1923). The author of A Man and an Institution: Sir Maurice Hankey (1984) has argued: "Although the foreign secretary sat in the peacetime cabinet, Hankey continued his close association with Lloyd George in world meetings, serving as secretary of the British delegation to the Washington naval conference (1921–2) and the Genoa conference (1922); the latter meeting witnessed Lloyd George's last exclusion of the foreign secretary from its councils."

When the David Lloyd George coalition fell in 1922 Hankey remained in place and in 1923 he became clerk of the privy council. He worked closely with the new prime minister, Andrew Bonar Law and served as secretary-general to conferences dealing with German reparations, in London (1924). He also served Ramsay MacDonald at the Hague Conference (1929) and the London Naval Conference (1930), although he disagreed with his foreign policies.

Hankey worked with Neville Chamberlain in the development of his appeasement policy. John F. Naylor has argued: " Though not close to Neville Chamberlain, Hankey strongly supported his policy of appeasement, albeit for reasons of military weakness rather than the premier's sense of mission. His dealings with cabinet ministers were a model of gentlemanly manners and moderation, although on occasion pent-up frustration spilled over into critical diary entries, which served in part as a release of his own convictions and emotions." In 1937 he wrote in his diary that Winston Churchill was "the most difficult man I ever had to work with".

In July 1938 Hankey retired as clerk of the privy council office, secretary to the cabinet, and secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence. He was created a peer in February 1939, but on the outbreak of the Second World War he accepted the position of minister without portfolio and membership in Chamberlain's war cabinet. He wrote that "as far as I can make out my main job is to keep an eye on Winston!" Other duties included the monitoring of intelligence activities and the application of science and technology to the war effort.

Winston Churchill appointed Hankey as Paymaster General in July 1941. The author of A Man and an Institution: Sir Maurice Hankey (1984) has argued: "Hankey had read the signs of his loss of standing in the ministry, but he persisted in his criticism of Churchill's conduct of the war especially during its darkest hours in the winter of 1941–2. His criticisms ranged from Churchill's war organization and dictatorial methods to a number of strategic issues. The issue about which Hankey felt most strongly was the imperative to divert converted long-range bombers away from strategic mainland bombing, and to use them to protect the lifeline of Atlantic convoys. His criticisms were not without merit, but he shared the particulars with a number of the prime minister's political opponents. Since his dissenting views were openly argued within the government he could not be accused of covert disloyalty, but predictably the breach widened." Hankey was dismissed by Churchill in March 1942.

After leaving office Hankey resumed his role as a director of the Suez Canal Company. In 1948 he served as a commercial director, consistently defending the company's role and the British military presence in Egypt. It is believed that Hankey lost a considerable amount of money when Colonel Gamar Abdel Nasser nationalized the company in 1956.

Books by Hankey include Government Control in War (1945), Diplomacy by Conference (1946), and Politics, Trials and Errors (1949), where he suggested a general amnesty for war criminals in the Second World War. He also published and The Supreme Command, 1914-1918 (1961).

George Mallaby has commented that "He (Hankey) was busy always, and his moods of relaxation were known only to his family... He took a cold bath every morning, he was an advocate of alfresco meals in unwelcoming weather, he was persistent in physical exercise, and his favourite method of locomotion was on his feet. He was a man of temperate habits. He preferred a diet of whole-wheat bread, raw vegetables, fresh fruit, eggs, and nuts, and this sustained him in full vigour until he was nearly eighty-six."

Sir Maurice Hankey, suffering from prostate cancer, died in Redhill General Hospital, on 26th January 1963.

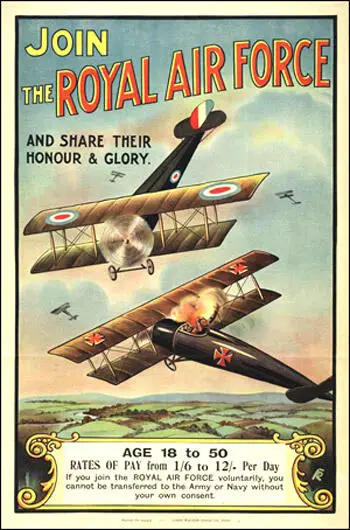

On this day in 1918 the Royal Air Force (RAF) is created. On the advice of General Jan Smuts, it was decided to form the RAF by amalgamating the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Also formed at this time was Women's Royal Air Force (WRAF). Under the leadership of Helen Gwynne-Vaughan, the next nine months saw 9,000 women recruited as clerks, fitters, drivers, cooks and storekeepers.

General Hugh Trenchard was appointed chief of staff and by December, 1918, the RAF had more than 22,000 aircraft and 291,000 personnel, making it the world's largest airforce. Over the next twenty years the RAF was developed as a strategic bombing force. One of the most important figures in this was Air Chief Marshal Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, who was Commandant of the RAF Staff College (1926-30) and Director of Operations and Intelligence at the Air Ministry before being appointed Commander in Chief of Bomber Command in 1937.

A fleet of light and medium monoplane bombers were developed during this period, notably the Vickers Wellington. The RAF also obtained two fast, heavily armed interceptor aircraft, the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire, for defence against enemy bombers.

The British government grew increasingly concerned about the growth of the Luftwaffe in Nazi Germany and in 1938 Vice Marshal Charles Portal, Director of Organization at the Air Ministry, was given the responsibility of establishing 30 new air bases in Britain.

In September 1939 Bomber Command consisted of 55 squadrons (920 aircraft). However, only about 350 of these were suitable for long-range operations. Fighter Command had 39 squadrons (600 aircraft) but the RAF only had 96 reconnaissance aircraft.

On this day in 1924 Agnes Smedley writes a letter to Florence Lennon about being a young woman in America. "When I was a girl, the West was still young, and the law of force, of physical force, was dominant. Women were desired, of course, but the rough-and-ready woman made her place, and often the women of the West, the mothers of large families, etc., were big, strong, dominant women. A woman who was not that was scorned, because the West had no use for "ladies." And the woman who could win the respect of man was often the woman who could knock him down with her bare fists and sit on him until he yelled for help. At least this was so in my class, which was the working class. Of course my mother, being frail, quiet, and gentle, died at the age of 38, of no particular disease, but from great weariness, loneliness of spirit, and unendurable suffering and hunger. She wasn't big enough to hammer my father when he didn't bring home the wages, and so we starved, and she starved the most of all so that we children might have a little food. And my father, a man of tremendous imagination - a Peer Gynt - lived in a world of dreams; the minute he had a little money, he went on a huge carouse in which reality played no part, in which he dreamed of himself as a great hero achieving the impossible, etc. Now, being a girl, I was ashamed of my body and my lack of strength. So I tried to be a man. I shot, rode, jumped, and took part in all the fights of the boys. I didn't like it, but it was the proper thing to do. So I forced myself into it, I scorned all weak womanly things. Like all my family and class, I considered it a sign of weakness to show affection; to have been caught kissing my mother would have been a disgrace, and to have shown affection for my father would have been a disaster. So I remember having kissed my mother only when she went on a visit to another town to see a relative; and I kissed my father but twice - once when he was drunk, because I read in a book that once a girl kissed her drunken father and reformed him and he never drank again!"

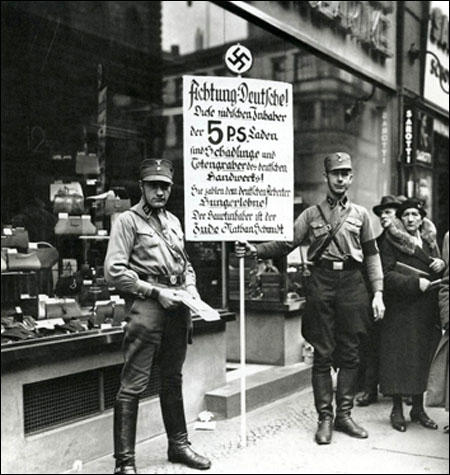

On this day in 1933 the recently elected Adolf Hitler organized a one-day boycott of all Jewish-owned businesses in Germany. Once in power Hitler began to openly express anti-Semitic ideas. Based on his readings of how blacks were denied civil rights in the southern states in America, Hitler attempted to make life so unpleasant for Jews in Germany that they would emigrate. SA members hunted down Jews in Berlin and gave them savage beatings. Synagogues were trashed and all over Germany gangs of brownshirts attacked Jews. In the first three months of Hitler rule, over forty Jews were murdered.

Hitler announced a boycott of Jewish businesses. Members of the SA picketed the shops to ensure the boycott was successful. As a child Christa Wolf watched the SA organize the boycott of Jewish businesses. "A pair of SA men stood outside the door of the Jewish shops, next to the white enamel plate, and prevented anyone who could not prove that he lived in the building from entering and baring his Aryan body before non-Aryan eyes."

Armin Hertz was only nine years old at the time of the boycott. His parents owned a furniture store in Berlin. "After Hitler came to power, there was the boycott in April of that year. I remember that very vividly because I saw the Nazi Party members in their brown uniforms and armbands standing in front of our store with signs: "Kauft nicht bei Juden" (Don't buy from Jews). That of course, was very frightening to us. Nobody entered the shop. As a matter of fact, there was a competitor across the street - she must have been a member of the Nazi Party already by then - who used to come over and chase people away."

the German economy and pay their German employees starvation wages.

The main owner is the Jew Nathan Schmidt.” (1st April, 1933)

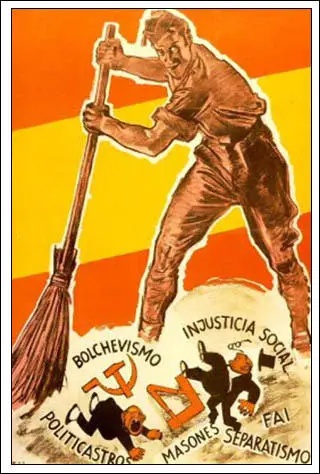

On this day in 1939 General Francisco Franco announces the end of the Spanish Civil War. Available information suggests that there were about 500,000 deaths from all causes during the war. An estimated 200,000 died from combat-related causes. Of these, 110,000 fought for the Republicans and 90,000 for the Nationalists. This implies that 10 per cent of all soldiers who fought in the war were killed. It has been calculated that the Nationalist Army executed 75,000 people in the war whereas the Republican Army accounted for 55,000. These deaths takes into account the murders of members of rival political groups.

It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others). The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion.

On this day in 1940 J. A. Hobson, died. John Atkinson Hobson, the son of William Hobson, the owner of the Derbyshire & North Staffordshire Advertiser, and Josephine Atkinson, was born in Derby on 6th July 1858. He studied at Derby Grammar School and Lincoln College, Oxford, and afterwards taught classics and English literature at schools in Faversham and Exeter.

In 1887 Hobson moved to London where he met the journalist William Clarke, who invited him to join the Fabian Society. An active member he wrote two books for the organization, Problems of Poverty (1891) and Problem of the Unemployed (1896). Other books published during this period included the Evolution of Modern Capitalism (1894) and John Ruskin: Social Reformer (1898).

C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, recruited Hobson to be the newspaper's correspondent in South Africa. While reporting on the country he developed the idea that imperialism was the direct result of the expanding forces of modern capitalism. Soon after returning to England in 1900 Hobson went on a lecture tour of the country. A strong opponent of the Boer War, Hobson condemned it as a "conflict orchestrated by and fought for the preservation of finance capitalism at the expense of the working class."

Over the next few years Hobson published several books exploring the links between imperialism and international conflict. This included War in South Africa (1900) and Psychology of Jingoism (1901). In his book Imperialism (1902), Hobson argued that imperial expansion was driven by a search for new markets and opportunities for investment overseas. These three books helped Hobson obtain an international reputation and influenced political figures such as Lenin and Leon Trotsky.

Hobson continued to write for the Manchester Guardian and his relationship with C. P. Scott became even closer after the editor's son, Edward Scott, married Hobson's daughter, Mabel. Hobson also contributed to journals such as the English Review, the Independent Journal and the Nation.

In his book The Industrial System (1909), Hobson argued that maldistribution of income led, through oversaving and underconsumption, to unemployment and that the remedy lay in eradicating the "surplus" by the redistribution of income through taxation and the nationalization of monopolies. Some have argued that David Lloyd George was influenced by this ideas and this was reflected in his People's Budget of 1909.

Hobson was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War and in 1914 joined the Union of Democratic Control, and served on its executive council. In his book Towards International Government (1914) he advocated the formation of a world body to prevent wars. However, he was highly critical of the League of Nations, as he believed it was little more than a "New Holy Alliance of the victors". He was also a savage critic of the Versailles Treaty.

In 1919 Hobson joined the Independent Labour Party. He wrote for socialist publications such as the New Leader, the Socialist Review and the New Statesman. A socialist, Hobson rejected the theories of Karl Marx and favoured the reform of capitalism rather than a communist revolution. A severe critic of the Labour Government formed by Ramsay MacDonald in 1929, Hobson rejected the offer of a peerage in 1931.

Hobson's autobiography, Confessions of an Economic Heretic, was published in 1938. He wrote his last article for the New Statesman in December 1939 where he expressed the hope that America would join the war, which he believed would shorten the conflict.

John Atkinson Hobson died on 1st April, 1940.

On this day in 1945 United States Army land on Okinawa. After the capture of Iwo Jima in March, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, turned his attentions to the island of Okinawa. Lying just 563km (350 miles) from the Japanese mainland, it offered excellent harbour, airfield and troop-staging facilities. It was a perfect base from which to launch a major assault on Japan, consequently it was well-defended, with 120,000 troops under General Mitsuru Ushijima. The Japanese also committed some 10,000 aircraft to defending the island.

After a four day bombardment the 1,300 ship invasion forced moved into position off the west coast of Okinawa on 1st April 1945. The landing force, under the leadership of Lieutenant-General Simon Buckner, initially totalled 155,000. However, by the time the battle finished, more than 300,000 soldiers were involved in the fighting. This made it comparable to the Normandy landing in mainland Europe in June, 1944.

Ushijima decided not to put his men on the coast where they would be subjected to US Naval heavy bombardment. Instead they were positioned at the southern end of the 60 mile long island on the volcanic mountain of Shuri.

On the first day 60,000 troops were put ashore against little opposition at Haguushi. The following day two airfields were captured by the Americans. However when the soldiers reached Shuri they came under heavy fire and suffered heavy casualties.

Reinforced by the 3rd Amphibious Corps and the 6th Marine Division the Americans were able to repel a ferocious counter-attack by General Mitsuru Ushijima on 4th May. At sea off Okinawa a 700 plane kamikaze raid on 6th April sunk and damaged 13 US destroyers. The giant battleship, Yamato, lacking sufficient fuel for a return journey, was also sent out on a suicide mission and was sunk on 7th May.

On 11th May, Lieutenant-General Simon Buckner, ordered another offensive on the Shuri defences, and the Japanese were finally forced to withdraw. Buckner was killed on 18th June and three days later his replacement, General Roy Geiger, announced that the island had finally been taken. When it was clear that he had been defeated, Mitsuru Ushijima committed ritual suicide (hari-kiri).

The capture of Okinawa cost the Americans 49,000 in casualties of whom 12,520 died. More than 110,000 Japanese were killed on the island.

While the island was being prepared for the invasion of Japan, a B-29 Superfortress bomber dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima on 6th August 1945. Japan did not surrender immediately and a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. On 10th August the Japanese surrendered and the Second World War was over.

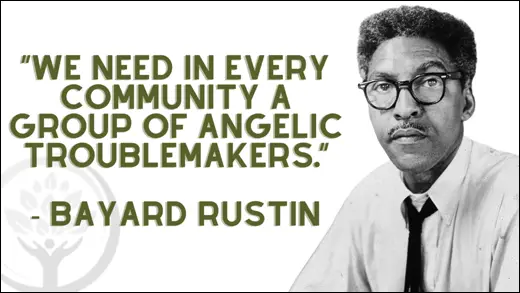

On this day in 1947 Bayard Rustin writes article for Louisiana Weekly on the use of non-violence in the struggle for civil rights. "I am sure that Marshall is either ill-formed on the principles and techniques of nonviolence or ignorant of the process of social change. Unjust social laws and patterns do not change because supreme courts deliver just decisions. One needs merely to observe the continued practice of Jim Crow in interstate travel, six months after the Supreme Court's decision, to see the necessity of resistance. Social progress comes from struggle; all freedom demands a price. At times freedom will demand that its followers go into situations where even death is to be faced. Resistance on the buses would, for example, mean humiliation, mistreatment by police, arrest, and some physical violence inflicted on the participants. But if anyone at this date in history believes that the "white problem," which is one of privilege, can be settled without some violence, he is mistaken and fails to realize the ends to which men can be driven to hold on to what they consider their privileges. This is why Negroes and whites who participate in direct action must pledge themselves to non-violence in word and deed. For in this way alone can the inevitable violence be reduced to a minimum."