Armin Hertz

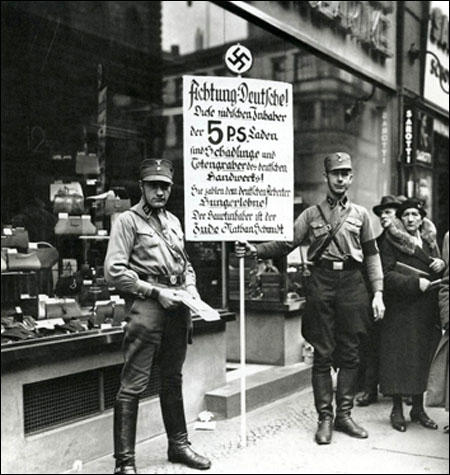

Armin Hertz was born in Berlin in 1924. The family owned a furniture shop in the city. His parents, who were Jewish, divorced in 1930 and was raised by his mother. Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933: "After Hitler came to power, there was the boycott (of Jewish shops) in April of that year." (1)

Armin remembers the children being allowed to sing Hitler Youth songs in the classroom: "The anti-Semitism was very vivid in school... They were trying to teach us Nazi songs. I vividly remember this song they were marching in the street with. The Hitler Youth, young boys actually of our age, were singing, Das Judenblut vom Messer spitzt, geht's uns nochmal so gut. (The Jews' blood spurting from the knife makes us feel especially good). They were also singing it in the school.... There were not many other Jews in my school, and then my mother took us out of that school and we went to a Jewish school. A decree had come out that Jewish teachers were not allowed to teach anymore in public schools. Therefore, there was no shortage of teachers in the Jewish schools. We went to a Jewish school and for us, of course, that was better." (2)

the German economy and pay their German employees starvation wages.

The main owner is the Jew Nathan Schmidt.” (1st April, 1933)

Armin Hertz said the Nazi campaign to boycott Jewish shops gradually got worse. "I saw the Nazi Party members in their brown uniforms and armbands standing in front of our store with signs: "Kauft nicht bei Juden" (Don't buy from Jews). That of course, was very frightening to us. Nobody entered the shop. As a matter of fact, there was a competitor across the street - she must have been a member of the Nazi Party already by then - who used to come over and chase people away." (3)

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

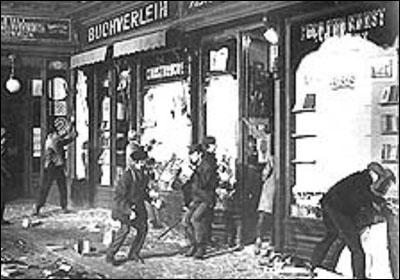

Ernst vom Rath was murdered by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on 9th November, 1938. At a meeting of Nazi Party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that night there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (4) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the police should not interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (5)

Heinrich Mueller, head of the Secret Political Police, sent out an order to all regional and local commanders of the state police: "(i) Operations against Jews, in particular against their synagogues will commence very soon throughout Germany. There must be no interference. However, arrangements should be made, in consultation with the General Police, to prevent looting and other excesses. (ii) Any vital archival material that might be in the synagogues must be secured by the fastest possible means. (iii) Preparations must be made for the arrest of from 20,000 to 30,000 Jews within the Reich. In particular, affluent Jews are to be selected. Further directives will be forthcoming during the course of the night. (iv) Should Jews be found in the possession of weapons during the impending operations the most severe measures must be taken. SS Verfuegungstruppen and general SS may be called in for the overall operations. The State Police must under all circumstances maintain control of the operations by taking appropriate measures." (6)

A large number of young people took part in what became known as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night). (7) Erich Dressler was a member of the Hitler Youth in Berlin. "Of course, following the rise of our new ideology, international Jewry was boiling, with rage and it was perhaps not surprising that, in November, 1938, one of them took his vengeance on a counsellor of the German Legation in Paris. The consequence of this foul murder was a wave of indignation in Germany. Jewish shops were boycotted and smashed and the synagogues, the cradles of the infamous Jewish doctrines, went up in flames. These measures were by no means as spontaneous as they appeared. On the night the murder was announced in Berlin I was busy at our headquarters. Although it was very late the entire leadership staff were there in assembly, the Bann Leader and about two dozen others, of all ranks.... I had no idea what it was all about, and was thrilled to learn that were to go into action that very night. Dressed in civilian clothes we were to demolish the Jewish shops in our district for which we had a list supplied by the Gau headquarters of the NSKK, who were also in civilian clothes. We were to concentrate on the shops. Cases of serious resistance on the part of the Jews were to be dealt with by the SA men who would also attend to the synagogues." (8)

Armin Hertz later explained what happened that night: "During the Kristallnacht, our store was destroyed, glass was broken, the synagogues were set on fire. There was a synagogue in the same street where we lived. It was on the first floor of a commercial building; downstairs were stores, and upstairs was a synagogue. In the back of that building, there was a factory so they could not set that synagogue on fire because people were living and working there. But they threw everything out of the window - the Torah scrolls, the prayer books, the benches, everything was lying in the street." (9)

Life in Belgium

After Kristallnacht it was impossible for the Hertz family to stay in Berlin because there was no way of earning a living. The plan was to go to England. Armin and his brother, set off first but was detained in Belgium: "The Belgian police were pretty lenient. They gave us a temporary permit to stay there for three months. You could get this as long as the Jewish committee would give you a paper saying that they would support you, that you would not be a burden to the state, and that you were not working."

Armin's mother, who left later, did manage to reach London but the "English government would not give us permission to go there to join her. Although there was a Jewish committee that was helping us, we were stuck and it was a desperate situation." After the outbreak of the Second World War Armin and his brother became more desperate to reach England. The situation became even more dangerous when the German Army invaded in May 1940.

Armin Hertz was identified as a Jew. "The German occupation forces imposed the same laws against the Jews that they had done in Germany: they made you wear the Jewish star, Jews were not allowed to go out in the street after seven or eight, and they started to round up people to send away. At that time we didn't know anything about concentration camps. We had no idea what was happening in Poland, in the east. They said they were sending people away to work; they would be in labor camps and get their rations there and wouldn't have to worry. In the beginning people actually volunteered because they had no money and the official rations were very small. To buy extra food on the black market was very expensive and they had no money. They thought that if they would go to work, they would get better food. After a while, we found out that those people who went voluntarily to these work camps never returned. So people stopped volunteering." (10)

Hertz was eventually arrested and sent to France to help build the Atlantic Wall, "a wall as thick as a house that went from Holland all the way through Belgium and France". It was very heavy work: "It was close to the beaches where they had to build defense positions. Our job was to carry water and cement. Sand they got from the beaches, but the cement we had to carry in cement bags. The sanitary conditions in that camp were very poor for toilets we had to dig a huge ditch. I contracted typhoid fever there. The guards got afraid because of that. There were five of us who had typhoid fever. They then took us to a French hospital and put us up in the basement. That was the first time in weeks that we slept in a clean bed. In the beginning we couldn't eat because we had such high temperatures."

Auschwitz

After he recovered his health he was sent back to a camp in Belgium. However, on 31st October, 1942, he was sent to Auschwitz: "This was the sixteenth transport from Mechelen. They gave us a card with a string to put around our neck, and we got a number-my number was 569.... There were 848 men, 94 women, and 41 children. Of the men, 54 returned. None of the women returned; none of the children returned. From 983, a total of 54 men returned. When we got to Auschwitz, the train stopped and they opened up the cars. Everybody had to get out. Right away they separated the women and the children to one side and the men had to go to the other side. Then we saw some men trying to whisper to us who were working around the train with striped uniforms on and their hair shaved off. They were saying, Walk! We couldn't figure out what that meant, but we soon found out. The camp was a short distance away. Anyone who was tired or felt that he couldn't walk was to go to the other side and supposedly there would be trucks that would pick them up and bring them to the camp. The people that were able to walk were to march. We got the message and we lined up to march to the camp. The other people that could not walk, or didn't want to, we never saw again. They went straight to the gas chamber."

Armin Hertz later described what happened when they got to the concentration camp. "In Auschwitz they had brick barracks. Two floors, a ground floor that held about four hundred people and six hundred people upstairs. Then came the barbers and they shaved our hair off. Then they put numbers on our arm - I had number 72552. All that put us in shock because nobody would expect that. They took everything away from us. We got these pajama-like uniforms and wooden shoes like those Dutch shoes, very uncomfortable to work with. And then we got a big speech from a man who was in charge of the block. He said, You are going to work here. This is a work camp. There is no escape from here. The only way you can get out of here is through the chimney." (11)

Hertz's work included digging ditches for water-lines. The Germans were building factories and enlarging the camp. "It was very hard work and the rations they gave us were not enough to survive on. Every day they gave you a piece of bread that was divided into four pieces. Each one of us got one quarter - that was the ration for the day. Then you had a bowl of so-called soup. You also had tea... it was made of leaves of trees."

On 18th January, 1945, Auschwitz was evacuated because of the progress being made by the Red Army. "We could already hear the bombardments and the artillery fire from the heavy cannons. They marched us toward Germany. That was the death march. Anybody who could not follow was just shot and left on the roadside. There was snow and ice; it was very cold... We slept nights in open fields and hundreds of people just died." (12)

Armin Hertz eventually got to the town of Breslau. On 26th February, 1945, they were taken to Reichenau: "There they put us again on open cars, about one hundred people in one car, with no food and a bucket in the middle for sanitary needs. We rode on that train for about six days and five nights. People were dying like flies. We had no water, no food, nothing. Once in a while it snowed, so we had a little water from the snow. The train stopped many times en route. Sometimes it stopped near a station on a siding and they left the train standing there for a whole day because they needed that locomotive to push another train, a through train or a supply train for the army. While we were there and when we saw a civilian nearby, we used to scream and yell, but they wouldn't give us anything.... When we arrived in Buchenwald, they opened up the train and the few people that were still alive could hardly walk. I, myself - my toes were frozen - have no toes left; all of them fell off."

Hertz found that Buchenwald was an improvement on Auschwitz: "In Buchenwald, the administration of the camp was political prisoners, not all necessarily communists, but democrats, socialists, lawyers, and intellectuals who were against the Nazi regime. These were nice people. They really wanted to help us, not like in Auschwitz. They had very little that they could give us, but whatever they had they shared. They tried to do the best they could. I myself couldn't walk. They had taken off my shoes; they had to cut them off actually because my feet were frozen and my toes almost fell off by themselves... We had bunks where four to five people slept in a line with a little straw for a bed; there were four levels. The commandant decided that the sick people didn't need the full ration anymore because they didn't work. They didn't give us any bread anymore. They only gave us that soup, so-called soup. We were very, very sick. If that would have lasted another day or two, I would not have made it." (13)

On 11th April, 1945, the United States Army arrived at the camp. Armin Hertz was close to death and was immediately taken to the local hospital: "There were regular beds and German doctors and nurses who took care of us. These nurses and doctors claimed they didn't know there was such a camp. Nobody knew what went on. But we knew that throughout the years the prisoners from Buchenwald went into the city of Weimar and cleaned the streets, dug ditches there, did excavations, and whatever. If they dropped a bomb, they took them out there to defuse the bombs. So they must have seen them because they also were wearing these striped uniforms. But they claimed they did not know."

Hertz recalled that he was fortunate to be taken to the hospital: "We were very fortunate they sent us to this hospital, because the other prisoners that were a bit healthier, who could walk by themselves, they put up in the SS barracks.... The American soldiers wanted to be good to us. They gave us all the food they had. That was a big problem because many people died because they ate all this food. They could not digest it because their intestines were all tied up. In the hospital they knew how to handle this. They gave us special food - just cereal with water and maybe skim milk. Every day they slightly increased the fat content of the rations that they gave us until we got better." (14)

On 5th May, 1945, Armin Hertz travelled to Brussels. He discovered that his brother had survived the war by hiding in the Ardennes, a region of extensive forests and mountains. He was eventually given permission to join his mother in England. Hertz later moved to the United States: "I got married and started a new life. I have two lovely daughters and four grandchildren. We try not to remember. It's not easy. For thirty-six years, I couldn't talk about it. I'm able to speak freely about it now. My wife can tell you that for years I used to wake up at night soaked in sweat. When I came to this country, if I saw a policeman on the street, I used to walk over to the other side of the street. It was not easy." (15)

Primary Sources

(1) Armin Hertz, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

The anti-Semitism was very vivid in school... They were trying to teach us Nazi songs. I vividly remember this song they were marching in the street with. The Hitler Youth, young boys actually of our age, were singing, Das Judenblut vom Messer spitzt, geht's uns nochmal so gut. (The Jews' blood spurting from the knife makes us feel especially good). They were also singing it in the school.

(2) Armin Hertz, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

During the Kristallnacht, our store was destroyed, glass was broken, the synagogues were set on fire. There was a synagogue in the same street where we lived. It was on the first floor of a commercial building; downstairs were stores, and upstairs was a synagogue. In the back of that building, there was a factory so they could not set that synagogue on fire because people were living and working there. But they threw everything out of the window-the Torah scrolls, the prayer books, the benches, everything was lying in the street.

My mother was very worried about her sister, because she had two little children and in the back of the building where she lived there was also a synagogue. So we tried to get in touch with her by phone the next day, but nobody answered. My mother got desperate and said to me, "Get your bicycle and go to Aunt Bertha to see what's going on." As I was riding along the business district, I saw all the stores destroyed, windows broken, everything lying in the street. They were even going into the stores and running away with the merchandise. Finally, I got to my aunt's house and I saw a large crowd assembled in front of the store. The fire department was there; the police were there. The fire department was pouring water on the adjacent building. The synagogue in the back was on fire, but they were not putting the water on the synagogue. The police were there watching it. I mingled with the crowd. I didn't want to be too obvious. I didn't want to get into trouble. But I heard from people talking that the people who lived there were all evacuated, all safe in the neighborhood with friends. So I went right back and reported to my mother. After Kristallnacht our store was destroyed and it was impossible to stay in Berlin.

(3) Armin Hertz, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

The German occupation forces imposed the same laws against the Jews that they had done in Germany: they made you wear the Jewish star, Jews were not allowed to go out in the street after seven or eight, and they started to round up people to send away. At that time we didn't know anything about concentration camps. We had no idea what was happening in Poland, in the east. They said they were sending people away to work; they would be in labor camps and get their rations there and wouldn't have to worry. In the beginning people actually volunteered because they had no money and the official rations were very small. To buy extra food on the black market was very expensive and they had no money. They thought that if they would go to work, they would get better food. After a while, we found out that those people who went voluntarily to these work camps never returned. So people stopped volunteering.

Then they started to round people up. They would take a block area, surround it with troops of the Wehrmacht, and they also had help from Belgian collaborators in the Rex Party. In one of those roundups, I was caught. They only wanted men at that time. They sent us by train to France to help build the Atlantic wall, a wall as thick as a house that went from Holland all the way through Belgium and France. They thought that the Allied invasion would come from that side.

It was very heavy work. The supervision of this camp was done by Organisation Todt. We had to build a fence around it ourselves. It was close to the beaches where they had to build defense positions. Our job was to carry water and cement. Sand they got from the beaches, but the cement we had to carry in cement bags. The sanitary conditions in that camp were very poorfor toilets we had to dig a huge ditch. I contracted typhoid fever there. The guards got afraid because of that. There were five of us who had typhoid fever. They then took us to a French hospital and put us up in the basement. That was the first time in weeks that we slept in a clean bed. In the beginning we couldn't eat because we had such high temperatures.

When we got better after a few weeks the guards showed up again and said, "We're sending you back to Belgium. You have to go back to the camp now." We did .go back to Belgium, but not back to the camp. They put us on regular passenger trains, with fifteen to twenty people in each compartment for eight, and brought us to Mechelen, which was an old army camp from World War I that the Germans used as an assembly point for all the Jews-men, women, and children-they had rounded up while we were in France. From there they added to our train another train with box cars, freight cars. This was the sixteenth transport from Mechelen. They gave us a card with a string to put around our neck, and we got a number-my number was 569. That was on October 31, 1942. There were 848 men, 94 women, and 41 children. Of the men, 54 returned. None of the women returned; none of the children returned. From 983, a total of 54 men returned.

When we got to Auschwitz, the train stopped and they opened up the cars. Everybody had to get out. Right away they separated the women and the children to one side and the men had to go to the other side. Then we saw some men trying to whisper to us who were working around the train with striped uniforms on and their hair shaved off. They were saying, "Walk!" We couldn't figure out what that meant, but we soon found out. The camp was a short distance away. Anyone who was tired or felt that he couldn't walk was to go to the other side and supposedly there would be trucks that would pick them up and bring them to the camp. The people that were able to walk were to march. We got the message and we lined up to march to the camp. The other people that could not walk, or didn't want to, we never saw again. They went straight to the gas chamber...

We had never heard of Auschwitz. We didn't know that a place like Auschwitz existed in 1942 at that time. They had said that there were shootings in Russia, in Ukraine where the Germans had advanced way back into Russia. There were rumors around in Belgium. We thought it was horrible, but we couldn't really believe it.

They did not just march us there to the camp and the gate with the large sign over it: "Arbeit macht frei". They forced us. They had these truncheons and they hit you over the head if you didn't walk fast enough. They brought us into a quarantine block. We went into the main camp. In Auschwitz they had brick barracks. Two floors, a ground floor that held about four hundred people and six hundred people upstairs. Then came the barbers and they shaved our hair off. Then they put numbers on our arm - I had number 72552. All that put us in shock because nobody would expect that. They took everything away from us. We got these pajama-like uniforms and wooden shoes like those Dutch shoes, very uncomfortable to work with. And then we got a big speech from a man who was in charge of the block. He said, "You are going to work here. This is a work camp. There is no escape from here. The only way you can get out of here is through the chimney." We didn't even understand what he meant by that.

(4) Armin Hertz, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

We went to the town of Breslau. There they put us on open cars and we got a lift to another camp, a very big camp. It was way overcrowded, terrible. They put us in a barrack with nothing for us to sleep on. We had to sit down on the floor and we couldn't even lie down. After a day or two they were looking for workers and we right away volunteered. They wanted about two hundred people to work in a factory nearby. We thought there couldn't be a place worse than this one was, so get out of it. When we arrived at the factory, it had been closed already for weeks. Soon we found out what they wanted us to do. The next morning they took us out to a clearance in the woods. They gave us shovels and they had us dig there. It was February 17, 1945. We left on February 26. Then they took us to a town named Reichenau. There they put us again on open cars, about one hundred people in one car, with no food and a bucket in the middle for sanitary needs. We rode on that train for about six days and five nights. People were dying like flies. We had no water, no food, nothing. Once in a while it snowed, so we had a little water from the snow.

The train stopped many times en route. Sometimes it stopped near a station on a siding and they left the train standing there for a whole day because they needed that locomotive to push another train, a through train or a supply train for the army. While we were there and when we saw a civilian nearby, we used to scream and yell, but they wouldn't give us anything. Finally, the train arrived in Buchenwald, Germany, near Weimar. In our car, there were 107 people. Anytime somebody died, we took their clothing off, put it around us to keep warm, and put the dead bodies over to one side. When we arrived in Buchenwald, they opened up the train and the few people that were still alive could hardly walk. I, myself - my toes were frozen - have no toes left; all of them fell off.

In Buchenwald, the administration of the camp was political prisoners, not all necessarily communists, but democrats, socialists, lawyers, and intellectuals who were against the Nazi regime. These were nice people. They really wanted to help us, not like in Auschwitz. They had very little that they could give us, but whatever they had they shared. They tried to do the best they could. I myself couldn't walk. They had taken off my shoes; they had to cut them off actually because my feet were frozen and my toes almost fell off by themselves...

We had bunks where four to five people slept in a line with a little straw for a bed; there were four levels. The commandant decided that the sick people didn't need the full ration anymore because they didn't work. They didn't give us any bread anymore. They only gave us that soup, so-called soup. We were very, very sick. If that would have lasted another day or two, I would not have made it.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)