On this day on 24th May

On this day in 1819 Alexandrina Victoria, the only child of Edward, Duke of Kent and Victoria Maria Louisa of Saxe-Coburg, was born. The Duke of Kent was the fourth son of George III and Victoria Maria Louisa was the sister of King Leopold of Belgium. The Duke and Duchess of Kent selected the name Victoria but her uncle, George IV, insisted that she be named Alexandrina after her godfather, Tsar Alexander II of Russia.

Victoria's father died when she was eight months old. The Duchess of Kent developed a close relationship with Sir John Conroy, an ambitious Irish officer. Conroy acted as if Victoria was his daughter and had a major influence over her as a child.

On the death of George IV in 1830, his brother William IV became king. William had no surviving legitimate children and soVictoria, became his heir. William's health was not good and he feared that Conroy would become the power behind the throne if Victoria became queen before she was eighteen.

William IV died 27 days after Victoria's eighteenth birthday. Although William was unaware of this, Victoria disliked Conroy and she had objected to his attempt to exert power over her. As soon as she became queen in 1837, Victoria banished Conroy from the Royal Court.

Lord Melbourne was Prime Minister when Victoria became queen. Melbourne was fifty-eight and a widower. Melbourne's only child had died and he treated Victoria like his daughter. Queen Victoria grew very fond of Melbourne and became very dependent on him for political advice. Melbourne was leader of the Whig party and although radical in his youth, his views were now extremely conservative. Melbourne had been a member of Earl Grey's government that had passed the 1832 Reform Act, but he had privately been against the measure. Melbourne attempted to protect Victoria from the harsh realities of British life and even advised her not to read Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens because it dealt with "paupers, criminals and other unpleasant subjects".

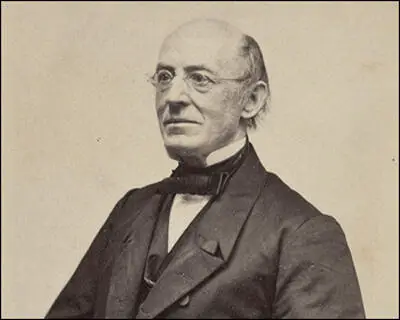

On this day in 1879 anti-slavery campaigner William Lloyd Garrison died. William Lloyd Garrison, the son of a seaman, was born in Newburyport Massachusetts, in December, 1805. Apprenticed as a printer, he became editor of the Newburyport Herald in 1824. Four years later he was appointed editor of the National Philanthropist in Boston.

In 1828 Garrison met Benjamin Lundy, the Quaker anti-slavery editor of the Genius of Universal Emancipation. The following year he became co-editor of Lundy's newspaper. One article, where Garrison's criticised a merchant involved in the slave-trade, resulted in him being imprisoned for libel.

Released in June 1830, Garrison's period in prison made him even more determined to bring and end to slavery. Whereas he previously shared Lundy's belief in gradual emancipation, Garrison now advocated "immediate and complete emancipation of all slaves". After breaking with Lundy, Garrison returned to Boston where he established his own anti-slavery newspaper, the Liberator. The newspaper's motto was: "Our country is the world - our countrymen are mankind" (an adoption of a comment made by Thomas Paine).

In the Liberator Garrison not only attacked slave-holders but the "timidity, injustice and absurdity" of the gradualists. Garrison famously wrote: "I am in earnest - I will not equivocate - I will not excuse - I will not retreat a single inch - and I will be heard." The newspaper only had a circulation of 3,000 but the strong opinions expressed in its columns gained Garrison a national reputation as the leader of those favouring immediate emancipation.

Garrison's views were particularly unpopular in the South and the state of Georgia offered $5,000 for his arrest and conviction. Garrison was highly critical of the Church for its refusal to condemn slavery. Some anti-slavery campaigners began arguing that Garrison's bitter attacks on the clergy was frightening off potential supporters.

In 1832 Garrison formed the New England Anti-Slavery Society. The following year he helped organize the Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison was influenced by the ideas of Susan Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone and other feminists who joined the society. This was reflected in the content of the Liberator that now began to advocate women's suffrage, pacifism and temperance.

Some members of the Anti-Slavery Society considered the organization to be too radical. They objected to the attacks on the US Constitution and the prominent role played by women in the society. In 1839, two brothers, Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, left and formed a rival organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

William Lloyd Garrison became increasingly radical and in 1854 he created controversy by publicly burning a copy of the Constitution at a Anti-Slavery rally at Framingham, Massachusetts. Although he doubted the morality of the violence used by John Brown at Harper's Ferry in 1859, his newspaper controversially supported his actions.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Garrison abandoned his previously held pacifist views and supported Abraham Lincoln and the Union Army. However, during the war, Garrison was critical of Lincoln for making the preservation of the union rather than the abolition of slavery his main objective.

After the passing of the 13th Amendment in 1865, Garrison decided to cease publication of the Liberator. Garrison spent his last fourteen years campaigning for women's suffrage, pacifism and temperance.

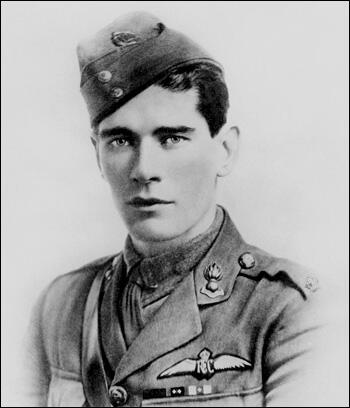

On this day in 1887 Mick Mannock, the son of Edward and Julia Mannock, was born at Preston Barracks, Brighton. Edward Mannock was a corporal in the Royal Scots regiment and the family was constantly on the move. As a child Mick lived in England, Scotland, Ireland and India.

While in India, Mick picked up an infection and went blind. Eventually he recovered his sight but for the rest of his life he had difficulty seeing out of his left eye. After Edward Mannock returned from the Boer War he deserted his wife and four children. Mick, who had suffered from his father's drunken rages, later revealed that he was pleased when he heard that his father had left the family home. However, the family were now very poor and Mick had to abandon his schooling at the earliest opportunity in order to bring in some much needed money. After a series of menial jobs, Mick found work as a telephone engineer.

Mick Mannock became interested in politics and as a young man became a committed socialist. Jim Eyles, a close friend later said that: "Mick told everyone he met that every man should prepare himself for the new age. The downtrodden of the world were about to get their chance at last; it was a duty for men to make the best of this opportunity for which the up-and-coming leaders of the new ideas had suffered so much." Mick spoke at political meetings and Jim Eyes later remarked how surprised he was that this young man "who had been dragged up in the most awful squalor, could match wits with these high-born and well-educated classes."

In February 1914, Mick Mannock's employers, the National Telephone Company, sent him to work in Turkey. When war was declared on 4th August 1914, Mick attempted to get back to England. Turkey had formed a defence alliance with Germany and Mick realised he was in danger. However, before he could arrange transport, Mick was arrested by the Turkish authorities and put into a concentration camp. After several attempts at escape, which resulted in long periods of solitary-confinement in a 6ft. cage, Mick was eventually allowed to leave for England in April 1915.

As soon as Mick Mannock arrived back home he joined the British Army. He was soon promoted to the rank of sergeant-major, but his health was poor and the army considered him unfit for military duties. In March 1916 he managed to obtain a transfer to the Royal Engineers as an officer cadet. Although he had very little formal schooling, Mick found he could compete with his well educated companions and was not long before he achieved the rank of Second Lieutenant.

In the summer of 1916, Mannock began reading in the newspapers about the exploits of Albert Ball, Britain's leading flying ace. Ball, who was not yet twenty years old, had already shot down eleven German aircraft. Mannock asked for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps and in August 1916, he was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics in Reading.

Mannock had a natural aptitude for flying. Captain Chapman, one of the men responsible for training Mick, later reported that: " He made his first solo flight with but a few hours' instruction, for he seemed to master the rudiments of flying with his first hour in the air and from then on threw the machine about how he pleased." Captain James McCudden, who was later to become one of Britain's leading flying aces, was another instructor who was impressed with Mick Mannock's skills as a pilot.

In March 1917, it was decided that Mannock was ready to be sent to the Western Front. Mannock arrived at St. Omer in France on 6th April 1917. At first Mannock's personality and political opinions upset the other pilots. Lieutenant Lional Blaxland later recalled his first impression of Mannock: "He was different. His manner, speech and familiarity were not liked. New men usually took their time and listened to the more experienced hands; Mannock was the complete opposite. He offered ideas about everything: how the war was going, how it should be fought, the role of scout pilots, what was wrong or right with our machines. Most men in his position, by that I mean a man with his background, would have shut up."

Soon after arriving in France, Mannock heard the news that Albert Ball, the man whose example had inspired him to join the Royal Flying Corps, had been shot down and killed. The same day, Captain Nixon, Mannock's patrol leader, was also killed during a mission to destroy German observation balloons.

Mannock had difficulty adjusting to combat duties and he had to wait until the 7th June 1917 before he made his first confirmed 'kill'. Before he could add to his total he received a wound to the head during a dogfight with two German pilots.

Mannock was sent back to England to recover. Mick went to stay with his mother but was dismayed to find that his mother, like his father, was now an alcoholic. He also discovered that his sister, Jessie, was working as a prostitute in Birmingham. Upset by the state of his family, Mick was anxious to get back to France, and desperately short of trained pilots, the RFC agreed that he could return to duty.

After returning to France in July, Mannock quickly developed a reputation as one of the most talented pilots in the RFC. In the first two weeks after arriving back at the Western Front he won four dogfights in his SE-5a. This gave him new confidence and on the 16th August he shot down four aircraft in a day. The following morning he added two more victories to his total. On the 17th September he won the Military Cross for driving off several enemy aircraft while destroying three German observation balloons. The following month he was awarded a bar to his Military Cross. The official citation read: "He attacked a formation of five enemy machines single-handed and shot one down out of control; while engaged with an enemy machine, he was attacked by two others, one of which he forced down to the ground."

Mannock was deeply affected by the amount of men he was killing. In his diary he recorded visiting the site where one of his victims had crashed near the front-line: "The journey to the trenches was rather nauseating - dead men's legs sticking through the sides with puttees and boots still on - bits of bones and skulls with the hair peeling off, and tons of equipment and clothing lying about. This sort of thing, together with the strong graveyard stench and the dead and mangled body of the pilot combined to upset me for a few days."

Mick Mannock was especially upset when he saw one of his victims catch fire on its way to the ground. From that date on, Mick Mannock always carried a revolver with him in his cockpit. As he told his friend Lieutenant MacLanachan: "The other fellows all laugh at me for carrying a revolver. They think I'm going to shoot down a machine with it, but they're wrong. The reason I bought it was to finish myself as soon as I see the first signs of flames."

Mannock's fear of fire was made worse by the British High Command's decision not to allow pilots in the Royal Flying Corps to carry parachutes. Mannock believed it was unfair to deny British airman to right to have parachutes when German pilots had been using them successfully for several months. He was especially angry about the main reason given for this decision: "It is the opinion of the board that the presence of such an apparatus might impair the fighting spirit of pilots and cause them to abandon machines which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair."

On 22nd July 1917, Mannock was promoted to captain. As flight commander he was able to introduce a new approach to combat flying. Mannock believed that the "days of the lone fighter was past and air fighting was now a matter for co-ordinated and planned fighting units which could inflict maximum damage and minimum losses."

In February 1918, Mannock became flight commander of 74 Squadron. The next three months saw thirty-six more victories. Mannock had now overtaken Albert Ball's total of forty-four kills and on 20th July he shot down a Albatros giving him fifty-eight victories, one more than the British record held by James McCudden. In June he was promoted to the rank of major and the following month became commander of 85 Squadron.

On 26th July, Major Mannock offered to help a new arrival, Donald Inglis, obtain his first victory. After shooting down an Albatros behind the German front-line, the two men headed for home. While crossing the trenches, the fighters were met with a massive volley of ground-fire. The engine of Mannock's aircraft was hit and immediately caught fire and crashed behind German lines. Mannock's body was found 250 yards from the wreck of his machine. He did not fire his revolver but it is believed he might have jumped from his blazing plane just before it crashed.

After his death, Mick Mannock was awarded the Victoria Cross for: "an outstanding example of fearless courage, remarkable skill, devotion to duty and self-sacrifice which has never been surpassed". Mannock's Victoria Cross was presented to his father at Buckingham Palace in July 1919. Edward Mannock was also given his son's other medals, even though Mick had stipulated in his will that his father should receive nothing from his estate. Soon afterwards Mannock's medals were sold for £5. They have since been recovered and can be seen at the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon.

On this day in 1904 saw the beginning of Empire Day. It was introduced by Reginald Brabazon, 12th Earl of Meath, "to nurture a sense of collective identity and imperial responsibility among young empire citizens". In schools, morning lessons were devoted to "exercises calculated to remind (the children) of their mighty heritage". The centrepiece of the day was an organised and ritualistic veneration of the Union flag. Then, schoolchildren were given the afternoon off, and further events were usually held in their local community. Empire Day became more of a sombre commemoration in the aftermath of First World War, and politically partisan as the Labour Party passed a resolution in 1926 to prevent the further celebration of Empire Day.

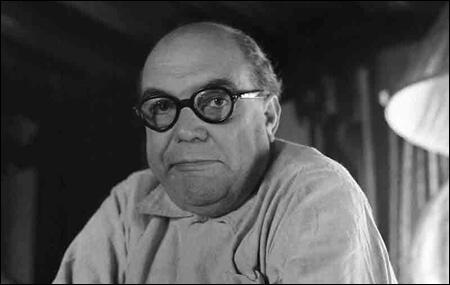

On this day in 1904 journalist Sefton Delmer was born in Berlin, Germany. His father, Frederick Delmer, was an Australian lecturer in English at Berlin University and on the outbreak of the First World War was interned as an enemy alien. In 1917 Delmer and his family were allowed to go to England.

Delmer was educated at Lincoln College, Oxford, where he obtained a second class degree in German. After leaving university he worked as a freelance journalist until being recruited by the Daily Express to become head of its new Berlin Bureau. While in Germany he became friendly with Ernst Roehm and he arranged for him to become the first British journalist to interview Adolf Hitler. In the 1932 general election Delmer travelled with Hitler on his private aircraft. He was also with Hitler when he inspected the Reichstag Fire. During this period Delmer was criticized for being a Nazi sympathizer and for a time the British government thought he was in the pay of the Nazi regime.

In 1933 Delmer was sent to France as head of the Daily Express Paris Bureau. He also covered important stories in Europe including the Spanish Civil War and the invasion of Poland by the German Army in 1939. He also reported on the German Western Offensive in 1940.

Sefton Delmer returned to England and in September 1940 he was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to organize "Black Propaganda" broadcasts to Nazi Germany. This included Soldatensender Calais, a pseudo-German radio station established in Crowborough for the German armed forces. Delmer's propaganda stories included spreading rumours that foreign workers were sleeping with the wives of German soldiers serving overseas. When Stafford Cripps discovered what Delmer was up to he wrote to Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary: "If this is the sort of thing that is needed to win the war, why, I'd rather lose it."

After the Second World War Delmer became chief foreign affairs reporter for the Daily Express. Over the next fifteen years Delmer covered nearly every major foreign news story for the newspaper. However, rumours began to circulate that Delmer was spying for the Soviet Union.

Lord Beaverbrook sacked Delmer in 1959 and he retired to Suffolk where he wrote two volumes of autobiography, Trial Sinister (1961), Black Boomerang (1962) and several other books including Weimar Germany (1972) and The Counterfeit Spy (1973).

Sefton Delmer died at Lamarsh, Suffolk, on 4th September 1979.

On this day in 1939 the British government discussed whether to open negotiations for an Anglo-Soviet alliance. The Cabinet was overwhelmingly in favour of an agreement. This included Lord Halifax who feared that if Britain did not do so the Soviet Union would sign an alliance with Nazi Germany. The Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain conceded that "in present circumstances, it was impossible to stand out against the conclusion of an agreement" but he stressed the "question of presentation was of the utmost importance." He therefore insisted that attempts should be made to hide any agreement under the banner of the League of Nations.

In June, 1939, a public opinion poll showed that 84 per cent of the British public favoured an Anglo-French-Soviet military alliance. Negotiations progressed very slowly and it has been claimed by Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998), that "Chamberlain did not seem to care less whether an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed at all, kept placing obstructions in the way of concluding an agreement swiftly." (244) Chamberlain admitted: "I am so sceptical of the value of Russian help that I should not feel that our position was greatly worsened if we had to do without them."

On this day in 1940 King George VI makes radio broadcast on the war. "The decisive struggle is now upon us. I am going to speak plainly to you in this hour of trial I know you would not have me do otherwise. Let no one be mistaken. It is no mere territorial conquest that our enemies are seeing. It is the overthrow, complete and final of this Empire and of everything for which is stands: and after that the conquest of the world. And if their will prevails they will bring to its accomplishment all the hatred and cruelty which they have already displayed. It was not easy for us to believe that designs no evil could find a place in the human mind. But the time for doubt is long past. To all of us in this Empire, to all men of wisdom and goodwill throughout the world, the issue is now plain. It is life or death for all."

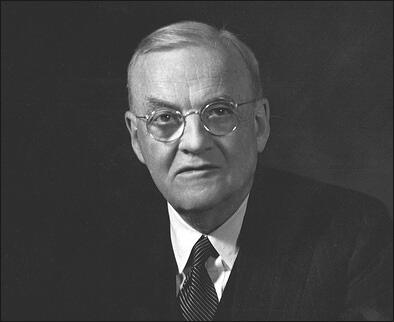

On this day in 1959 John Foster Dulles died. Dulles, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was born in Washington on 25th February, 1888. His brother was Allen Dulles and his grandfather was John Watson Foster, Secretary of State under President Benjamin Harrison. His uncle, Robert Lansing, was Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Woodrow Wilson.

After attending Princeton University and George Washington University he joined the New York law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell, where he specialized in international law. He tried to join the United States Army during the First World War but was rejected because of poor eyesight.

In 1918 Woodrow Wilson appointed Dulles as legal counsel to the United States delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference. Afterwards he served as a member of the War Reparations Committee. Dulles, a deeply religious man, attended numerous international conferences of churchmen during the 1920s and 1930s. He also became a partner in the Sullivan & Cromwell law firm.

Dulles was a close associate of Thomas E. Dewey who became the presidential candidate of the Republican Party in 1944. During the election Dulles served as Dewey's foreign policy adviser. In 1945 Dulles participated in the San Francisco Conference and worked as adviser to Arthur H. Vandenberg and helped draft the preamble to the United Nations Charter. He subsequently attended the General Assembly of the United Nations as a United States delegate in 1946, 1947 and 1950. He also published War or Peace (1950).

Dulles criticized the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman. He argued that the policy of "containment" should be replaced by a policy of "liberation". When Dwight Eisenhower became president in January, 1953, he appointed Dulles as his Secretary of State.

He spent considerable time building up NATO as part of his strategy of controlling Soviet expansion by threatening massive retaliation in event of a war. In an article written for Life Magazine Dulles defined his policy of brinkmanship: "The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art." His critics blamed him for damaging relations with communist states and contributing to the Cold War.

Dulles was also the architect of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) that was created in 1954. The treaty, signed by representatives of the United States, Australia, Britain, France, New Zealand , Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand, provided for collective action against aggression.

Dulles upset the leaders of several non-aligned countries when on 9th June, 1955, he argued in one speech that "neutrality has increasingly become an obsolete and except under very exceptional circumstances, it is an immoral and shortsighted conception."

In 1956 Dulles strongly opposed the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt (October-November). However, by 1958 he was an outspoken opponent of President Gamal Abdel Nasser and stopped him from receiving weapons from the United States. This policy backfired and enabled the Soviet Union to gain influence in the Middle East.

John Foster Dulles , suffering from cancer, was forced to resign from office in April, 1959.

On this day in 1964 Barry Goldwater suggests using nuclear weapons in Vietnam. "There have been several suggestions made. Defoliation of the forests by low-yield atomic weapons could well be done. When you remove the foliage, you remove the cover. We might have to (take action against China). Either that, or we have a war dragged out and dragged out. a defensive war is never won. If we decide to go into this war in a full-scale way, certainly we would have to make the decision on strategic supplies for the enemy at the same time."

On this day in 1995 Harold Wilson died. He first became prime minister as a result of the 1964 General Election the Labour Party obtained a swing of 3% to obtain victory. As Philip Ziegler pointed out: "Fewer people had voted, Labour in 1964 than in I959, even though the electorate was a larger one. A revived Liberal Party had secured some two million extra votes, some from Labour, more from the Tories. The Liberals in a sense had won the election for Harold Wilson. An overall Tory majority of almost a hundred had been overturned, to be replaced by so overall Labour majority of five."

Harold Wilson was furious with the defeat of Patrick Gordon Walker and called on Sir Alec Douglas-Home, the leader of the Conservative Party, to condemn the racist campaign of Peter Griffiths as he had previously agreed that the political parties would not exploit anti-immigrant feelings during the election. Wilson later wrote: "I asked him, then and there, to get up and say whether he endorsed the successful Conservative candidate, Peter Griffiths, or whether he repudiated the means by which he had entered the House. If the former, I said, then Sir Alec would have fallen a long way from the position he had taken up. If the latter, then the honourable member for Smethwick would, for the life-time of Parliament, be treated as a parliamentary leper. This created an immediate outcry and some Conservatives walked out in protest."

Some members of MI5 believed that Wilson was a Soviet agent. Anatoli Golitsyn also told them that Hugh Gaitskell had been poisoned by the KGB. Peter Wright, a senior figure in MI5, explained in his biography Spycatcher: "The story started with the premature death of Hugh Gaitskell in 1963. Gaitskell was Wilson's predecessor as Leader of the Labour Party. I knew him personally and admired him greatly."

After the 1966 General Election this majority was increased to 97. Wilson now carried out his promise to modernize Britain. During that period the House of Commons passed the 1965 Race Relations Act (outlawed discrimination on the "grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins" in public places), 1965 Abolition of Death Penalty Act (replaced the penalty of death with a mandatory sentence of imprisonment for life), 1967 Sexual Offences Act (it decriminalised homosexual acts in private between two men, both of whom had to have attained the age of 21), 1967 Abortion Act (it legalising abortions by registered practitioners, and regulating the free provision of such medical practices through the National Health Service), 1968 Theatres Act (abolished censorship of the stage), 1969 Divorce Reform Act (allowing couples to divorce after a separation of two years); Comprehensive Education (1966 to 1970, the proportion of children in comprehensive schools increased from about 10% to over 30%), Housing (1.3 million new homes were built between 1965 and 1970), Family Allowances (from April 1964 to April 1970, family allowances for four children increased as a percentage of male manual workers aged 21 and above from 8% to 11.3%.)

Wilson had more difficulty with the economy and in November, 1967, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, James Callaghan, was forced to devalue the pound. In 1968 Cecil King, the publisher of the Daily Mirror, became involved with Peter Wright of MI5 in a plot to bring down the government of Wilson. Wright claimed in his memoirs, Spycatcher (1987) that "Cecil King, who was a longtime agent of ours, made it clear that he would publish anything MI5 might care to leak in his direction."

Hugh Cudlipp arranged for King to meet Lord Mountbatten, the recently retired Chief of the Defence Staff, who had been privately highly critical of the defence cuts made by the government. Solly Zuckerman, the government's scientific adviser, was also invited to attend the meeting on 8th May. According to Cecil King's account in his memoirs, Without Fear or Favour (1971), when he told Mountbatten of his plans, he replied that "there is anxiety about the government at the palace, and that the queen has had an unprecedented number of letters protesting about Wilson".

According to Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay, the authors of Smear! Wilson and the Secret State (1992): "King then delivered a version of his preoccupations at the time - approaching economic collapse and ineffective government, with a Prime Minister no longer able to control events. Public order was about to break down leading to social chaos. there was a likelihood of bloodshed in the streets." At this point Zuckerman got up and said: "This is rank treachery. All this talk of machine guns at street corners is appalling." He also told Mountbatten to have nothing to do with the conspiracy to overthrow Wilson.

Two days later, King published an article in the Daily Mirror under his own name entitled "Enough is enough". It read: "Mr Wilson and his government have lost all credit and we are now threatened with the greatest financial crisis in history. It is not to be resolved by lies about our reserves but only by a fresh start under a fresh leader." Three weeks later the directors of International Publishing Corporation unanimously dismissed King.

By the end of the 1960s, with unemployment and inflation increasing, Wilson's popularity declined and the Conservative Party, led by Edward Heath, won the 1970 General Election. Heath successfully led Britain into the European Economic Community (ECC). However, many in his party was unhappy with this policy and it created deep divisions that lasted for over thirty years.

Edward Heath also came into conflict with the trade unions over his attempts to impose a prices and incomes policy. His attempts to legislate against unofficial strikes led to industrial disputes. In 1973 a miners' work-to-rule led to regular power cuts and the imposition of a three day week. Heath called a general election in 1974 on the issue of "who rules". He failed to get a majority and Wilson and the Labour Party were returned to power.

When Harold Wilson returned to power in 1974 Peter Wright once again became involved in a plot against the Labour government. It was suggested that MI5 files on Wilson should be leaked to the press. Wright was eventually persuaded by Victor Rothschild not to take part in the conspiracy. Rothschild warned him that he was likely to get a caught and if that happened he would lose his job and pension.

In 1975 Wilson decided to hold a referendum on membership of the European Economic Community. Wilson allowed his Cabinet to support both the Yes and No campaigns and this led to a bitter split in the party.

Wilson's government again had trouble with the economy. Faced with the prospect of having to get a loan from the International Monetary Fund, Wilson came under increasing attack from all sections of the Labour Party. Wilson was also suffering from the early signs of Alzheimer's Disease and in 1976 decided to resign from office and was replaced by James Callaghan.

Wilson was knighted in 1976 and was created Baron of Rievaulx in 1983.