On this day on 17th March

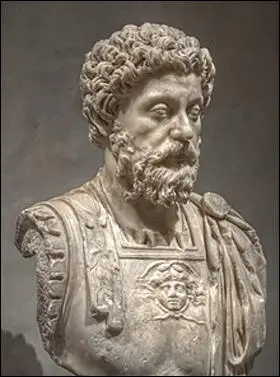

On this day in 180 Marcus Aurelius died. The son of Marcus Annius Verus and Domitia Lucilla, was born in Rome on 26th April 121 AD. Marcus had dozens of wealthy and influential relatives. His paternal grandfather, Marcus Annius Verus, was a Roman senator, whereas his maternal grandmother, Domitia Lucilla Maior, was an extremely wealthy woman who owned one of the largest brick factories in the Roman Empire.

Marcus' father, who had reached the rank of praetor, died in 124. As he was only three at the time he had no memory of his father. His mother did not remarry. Marcus later recalled that he learnt from his mother "piety and beneficence, and abstinence, not only from evil deeds, but even from evil thoughts; and further, simplicity in my way of living, far removed from the habits of the rich."

His grandfather took over the responsibility of bringing him up after the death of his father. Later, Marcus Aurelius commented that his grandfather had a major influence on his personality. "I learned good morals and the government of my temper."

Marcus Annius Verus was a loyal supporter of Emperor Hadrian and he made him aware of his grandson. Hadrian seemed to take a strong interest in the boy and when he was six years-old he promoted him into the equestrian class. The idea was that the boy would enter the senatorial order "by merit" when he officially become a man. This was an extremely rare honour for one so young.

At the age of eight Marcus "commenced his education in earnest". His grandfather insisted that he was educated at home with private tutors instead of sending him to school. Most oligarchic Roman families, insisted that their children be educated at home rather than at school. As Frank McLynn points out: "In the first place it was thought that schools were likely to corrupt the morals of the young, partly because they would come into contact with rougher, more depraved elements, and partly because there was little effective discipline in the public schools, with teachers either being martinets or pussycats, but seldom striking the right balance, and their charges being idle, ill-behaved, conceited or self-willed."

We do not know the name of his first tutor but according to Marcus he instructed him to reject the pleasures of chariot racing and the Roman Games. That only "lesser minds" supported the factions (Blues, Greens, Whites and Reds). He was taught "to be neither of the green nor of the blue party at the games in the Circus, nor a partisan either of the Parmularius or the Scutarius at the gladiators' fights; from him too I learned endurance of labour, and to want little, and to work with my own hands, and not to meddle with other people's affairs, and not to be ready to listen to slander."

Another teacher named Diognetus, encouraged him to reject the passions of most young boys: "not to busy myself about trifling things, and not to give credit to what was said by miracle-workers and jugglers about incantations and the driving away of daemons and such things; and not to breed quails for fighting, nor to give myself up passionately to such things; and to endure freedom of speech; and to have become intimate with philosophy; and to have been a hearer, first of Bacchius, then of Tandasis and Marcianus; and to have written dialogues in my youth; and to have desired a plank bed and skin, and whatever else of the kind belongs to the Grecian discipline." His mother, who did not play a major role in his upbringing, but when he was twelve she discovered him sleeping on the floor and forced him to give up "this nonsense" and sleep in a bed.

During his early years his most important teacher was a Greek who had been living in Syria, Alexander of Cotiaeum. He taught him about the use of language and states in The Meditations that he learnt "to refrain from fault-finding, and not in a reproachful way to chide those who uttered any barbarous or solecism or strange-sounding expression; but dexterously to introduce the very expression which ought to have been used, and in the way of answer or giving confirmation, or joining in an inquiry about the thing itself, not about the word, or by some other fit suggestion." In other words, the clever educator moves the discussion away from the error and subtly introduces the correct expression (of grammar, syntax or pronunciation), so that the student leans his error without being humiliated for having made it.

Marcus Aurelius was taught not to be a hedonist and to deny himself the pleasures of the flesh and resisted the temptation of having sex with attractive slaves, both boys and girls. "I am thankful to the gods... that I preserved the flower of my youth, and that I did not make proof of my virility before the proper season, but even deferred the time... that I never touched either Benedicta or Theodotus, and that, after having fallen into amatory passions, I was cured." Roman morals allowed males up to eighteen a bisexual period. His biographer points out: "Like many people who are not highly sexed, Marcus could never really understand what all the fuss was about when it came to Eros."

Emperor Trajan was a homosexual who never had any children. He therefore adopted Hadrian in order that he would succeed him when he died. Hadrian became emperor in 117 AD. He was also a homosexual and this caused problems for him during his reign. Roman culture accepted bisexuality until about the age of eighteen, but after that, he was expected to marry and raise a family. Hadrian rejected this convention and made no secret of his desire to have sex with young boys. As Tertullian pointed out, Hadrian was "an explorer of all the world's curiosities".

Hadrian's most famous lover was Antinous, who died in mysterious circumstances at the age of twenty. Some said that Antinous was drowned in the Nile by Hadrian's enemies. Others claimed that Hadrian's arranged his death to appease the gods. There were also other Romans who believed that he had committed suicide because Hadrian had rejected him and had taken a younger lover.

Hadrian also upset the Roman elite by his peace policy. His predecessor Trajan had won martial glory in Dacia (modern Romania) and Mesopotamia (most of Iraq, Kuwait, the eastern parts of Syria, and South-eastern Turkey), but immediately on coming to the throne, Hadrian abandoned all these eastern conquests and announced that he intended to consolidate the empire and there would be no more expansionism.

Emperor Hadrian travelled the Roman Empire more extensively than any previous emperor, visiting Gaul and the Rhine (120-121), Britain (121-122), Spain (122), Asia (123), Greece (125), Sicily (127) Africa (128), Caria, Cilicia, Cappadocia and Syria (129) and Egypt (130). Hadrian returned to Rome in 131 and spent the remainder of his reign in Italy.

In 132, Simon Bar Kokhba, led a rebellion of the Jews of the Roman province of Judea. The Romans suffered heavy casualties and soon most of Palestine was in Bar-Kochba's hands. Hadrian sent his best general, Sextus Julius Severus, who had been serving in Britain, to deal with the crisis. In 134 he began a war of attrition, never engaging the enemy in strength, but instead cutting off food supplies, severing communications and ambushing rearguards.

Bar-Kochba was finally besieged in the fortress of Bethar, six miles south-west of Jerusalem. Late in 135 the Romans took the stronghold and Bar-Kochba was killed. His severed head was taken to Sextus Julius Severus. According to the Roman historian, Cassius Dio, around 580,000 Jews were killed in war operations across the country, and some 50 fortified towns and 985 villages were razed to the ground, "while those who perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out". In the aftermath of the war, Hadrian consolidated the older political units of Judaea, Galilee and Samaria into the new province of Syria Palaestina.

Hadrian feared the power of the mob and the army. He believed the common people could be kept quiet by lavish shows in the arena, and specialised in providing them with wild-beast shows and sometimes had a hundred lions killed in a single spectacle. He dealt with the army by having an efficient spy system. He also encouraged people to inform on each other and "even encouraging wives to write to him with complaints about their husbands."

Emperors were expected to work closely with the Senate, but Hadrian refused. If he felt threatened by any politician, he had them executed. He suffered from paranoia and even forced his ninety-year-old, brother-in-law Lucius Julius Severianus, to commit suicide. His grandson, Pedanius Fuscus Salinator, was also executed. He initially selected Gaius Avidius Nigrinus to replace him, but changed his mind and in 118 he had him executed on a trumped-up charge of conspiracy.

On his sixty-second birthday, Hadrian announced his successor would be Antoninus Pius, aged fifty-two, a relatively unknown senator with limited experience of government. Hadrian "adopted" him to satisfy all the legal requirements. "Lying on his invalid's couch, Hadrian explained the reasons for his choice: in brief, it was Antoninus's very lack of distinction and his middle age, for an older man might be senile and make grievous mistakes, while a younger one might be rash and headstrong. From Hadrian's point of view, Antoninus was a perfect blank state: he was a steady character, had no real enemies or ongoing feuds, had no siblings and just one daughter surviving from five children; his two sons had both died young."

Hadrian insisted that in turn Antoninus Pius "adopted" Marcus Aurelius as his son and successor. In addition to adopting the 17-year-old Marcus, he also had to promise to marry his eight-year old daughter, Faustina. In his preparation to become emperor, Marcus was forced to leave his mother's villa to move into Hadrian's private home. Hadrian was seriously ill and demanding that his doctors kill him by euthanasia. They refused and Antoninus Pius explained to the dying emperor that it was his duty to endure pain rather than be put out of his misery. Antoninus also had to adopt the seven-year-old son of Aelius Verus. Marcus therefore gained Lucius Verus as a younger "brother".

Hadrian died on 10th July 138. Antoninus Pius immediately made it clear that, unlike Hadrian, would consult with the Senate before making any important decisions. He also abolished the much hated Italian circuit-judges instituted by Hadrian. Antoninus Pius was given the title Pater Patriae (Father of his Country). Over the next twenty-two years he succeeded in maintaining good relations with the senate.

According to one historian, "The senatorial order was also deeply relieved that Antoninus was rigidly conservative and had no inclination to tinker or experiment. Antoninus indeed believed that the empire was poised on a delicate equilibrium and that the slightest change might bring disaster, like removing an individual card from a house of cards... Antoninus essentially believed in change only so that everything would remain the same."

His economic and financial policies were austere and conservative. Although personally very wealthy, he was determined that his private fortune would not be swallowed up by the demands of the imperial throne, and deliberately created a government department to administer his private wealth and keep it distinct and separate from the money in the imperial treasury.

Despite his financial caution, like previous emperors, he provided regular gifts of money to the people and to the soldiers, as well as lavish Roman Games and other entertainments. The money he gave to the people was always termed largesse, while that to to the army was known as donations. In twenty-three years he doled out largesse worth 800 denarii a head, an average of thirty-five denarii a year. He gave donatives to the army on his accession, in 140 and again in 148. He also lent money at interest, charging a rate of 4 per cent when the market rate fluctuated between 6 and 12 per cent. Finally, he used his own funds to distribute free oil, grain and wine in periods of famine.

Antoninus, inspired by his Stoic teachers, had a spartan attitude towards money and took frugal meals and reduced the pomp of state occasions to republican simplicity. He enjoyed good health and argued strongly for health-giving qualities of dry bread. Tall and good-looking, he had a pleasant speaking voice but was not much of an orator. Contemporaries described him as intelligent, genial, kind, honest, hard-working, dutiful and dedicated to the affairs of the state.

Most of all, he was a highly successful leader: "He had a keen sense of the needs of the empire and, especially, of the treasury and was willing to take full responsibility (and blame if need be) for policies. Self-reliant and cheerful, he hated flattery and bogus acclamations, demagoguery and passing fads; by the same token, he detested sycophants and those who attempted to curry favour or pander to his supposed whims... He felt at ease with other people and could put them at their ease. His good health and good looks were remarkable, but he was never vain or hypochondriacal."

According to Marcus Aurelius: "He honoured those who were true philosophers, and he did not reproach those who pretended to be philosophers, nor yet was he easily led by them. He was also easy in conversation, and he made himself agreeable without any offensive affectation. He took a reasonable care of his body's health, not as one who was greatly attached to life, nor out of regard to personal appearance, nor yet in a careless way, but so that, through his own attention, he very seldom stood in need of the physician's art or of medicine or external applications. He was most ready to give way without envy to those who possessed any particular faculty, such as that of eloquence or knowledge of the law or of morals, or of anything else; and he gave them his help, that each might enjoy reputation according to his deserts; and he always acted conformably to the institutions of his country, without showing any affectation of doing so…. His secrets were not but very few and very rare, and these only about public matters; and he showed prudence and economy in the exhibition of the public spectacles and the construction of public buildings, his donations to the people, and in such things, for he was a man who looked to what ought to be done, not to the reputation which is got by a man's acts."

After the death of his wife, Faustina the Elder in 140, Antoninus refused to marry. Instead he took one of his wife's freedwomen, Galeria Lysistrata, as his mistress. This, plus his promise of his daughter, Faustina the Younger, to Marcus, showed very clearly that there would be no obstacle to his eventual ascent to the highest honour in the Roman Empire. In April 145 the marriage between Marcus and Faustina took place. "Marcus married at twenty-four, exactly the right age for a member of the senatorial class, and Faustina at fourteen, a little earlier than the usual age for aristocratic girls."

On becoming emperor, Antoninus, decided that Marcus should receive an education to prepare him for his future role as ruler of the Roman Empire. He read the works of Cinna Catulus, a Stoic philosopher, from whom he learned the following: "Not to shrug off a friend's resentment - even if it is justified - but to try to put things right. To show your teachers ungrudging respect and your children unfeigned love."

Apollonius of Chalcedon became one of his tutors. He taught that nothing mattered except the purity of Stoic doctrine: "From Apollonius I learned freedom of will and undeviating steadiness of purpose; and to look to nothing else, not even for a moment, except to reason; and to be always the same, in sharp pains, on the occasion of the loss of a child, and in long illness; and to see clearly in a living example that the same man can be both most resolute and yielding, and not peevish in giving his instruction; and to have had before my eyes a man who clearly considered his experience and his skill in expounding philosophical principles as the smallest of his merits; and from him I learned how to receive from friends what are esteemed favours, without being either humbled by them or letting them pass unnoticed."

Another influential tutor was Claudius Severus Arabianus, a follower of Aristotle, who instructed Marcus in the philosophical tradition of resistance to tyranny. A supporter of republican virtue and ancient Roman liberties and his main theme was the importance of reconciling imperial authority with liberty. Severus believed in freedom of speech, equality before the law and enlightened rulers. "He preached the love of family, truth and justice, the value of helping others, the joys of sharing and the merits of optimism. He advised Marcus always to be straightforward with people and to let them know exactly where they stood, never dissembling or harbouring long-term grudges as Hadrian used to do."

According to Marcus Aurelius: "From my brother Severus, to love my kin, and to love truth, and to love justice… I learned from him also consistency and undeviating steadiness in my regard for philosophy; and a disposition to do good, and to give to others readily, and to cherish good hopes, and to believe that I am loved by my friends; and in him I observed no concealment of his opinions with respect to those whom he condemned, and that his friends had no need to conjecture what he wished or did not wish, but it was quite plain."

Another great influence was the politician, administrator and Stoic philosopher, Claudius Maximus, who was well-known for his probity and integrity: "From Maximus I learned self-government, and not to be led aside by anything; and cheerfulness in all circumstances, as well as in illness; and a just admixture in the moral character of sweetness and dignity, and to do what was set before me without complaining."

Marcus Aurelius was sometimes in conflict with his most famous tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto. By the time he was appointed he had gained fame and wealth as an advocate and orator as to be reckoned inferior only to Cicero. It needs to be understood that truth was always the last consideration in Roman oratory. The object was to "manipulate a familiar arsenal of cosmological and psychological explanations to take the listener with you to a predestined end."

Fronto was considered a philistine who thought poetry pointless except to use it as a storehouse to be ransacked for words to be used in speeches. Marcus comments on Fronto only took up a couple of lines in The Meditations: "From Fronto I learned to observe what envy, and duplicity, and hypocrisy are in a tyrant, and that generally those among us who are called Patricians are rather deficient in paternal affection."

Fronto gave Marcus advice on how to rule Rome. In a letter written in 143 he wrote about how to use language to please the crowd. He argued that the future emperor should never alienate the all important masses when making a speech. Fronto, like many Romans, had a deep fear of the Roman mob and suggested that he should always give the people what they want. This included releasing felons or criminals if the crowd clamours for it.

It seems that Marcus Aurelius grew very fond of Herodes Atticus, a teacher of rhetoric. Fronto became very jealous of the relationship and was distraught when he was asked by Marcus to back-pedal on a case involving Herodes: "I know that you have often said to me, 'What can I do that will please you most?' Now is the time. If my love for you can be increased, you can increase it now... It is a favour I am asking you and, if you grant it, I promise to put myself in your debt in return." (40) Fronto later wrote: "I confess and make no secret of it, that I am your rival in his love - everything else is remediable and of infinitely less importance than this."

The most important influence on Marcus Aurelius was Antoninus Pius, the man who had adopted him: "In my father I observed mildness of temper, and unchangeable resolution in the things which he had determined after due deliberation; and no vainglory in those things which men call honours; and a love of labour and perseverance; and a readiness to listen to those who had anything to propose for the commonweal; and undeviating firmness in giving to every man according to his deserts; and a knowledge derived from experience of the occasions for vigorous action and for remission." Marcus shared Antoninus view on homosexuality: "And I observed that he (Antoninus) had overcome all passion for boys; and he considered himself no more than any other citizen."

Emperor Antoninus Pius was taken ill at the end of February, 161, at Lorium. Aged seventy-five, he declined rapidly and convinced he was at the point of death, he summoned Marcus Aurelius and the other members of the imperial council and formally commended him to them as the next emperor, expressing the wish that he would treat the empire as well as he had always treated his daughter Faustina. He died on 7th March and Cassius Dio recorded that it was a good death, "sweet and like the softest sleep".

Marcus Aurelius accepted the throne reluctantly and only on condition that the Senate appoint his adopted brother, Lucius Verus, as co-Emperor alongside him. "There was no precedent for rule by joint Emperors and there certainly had been no obligation on Marcus to force the issue on the Senate. The action demonstrates Marcus's clear intention to commence his reign as he meant to go on: by acting in accordance with what he held to be right and fair, even when this was in no way demanded or expected of him." To reinforce the arrangement, Marcus announced the betrothal of his eleven-year-old daughter Annia Lucilla. Verus, who was 18 years her senior, became her husband three years later in Ephesus in 164.

Marcus was forty when he became emperor. By this stage in his life he was physically frail and according to his own writings and biographical accounts written by others, he suffered poor health. He was an insomniac who hated getting out of bed in the morning. He was hypersensitive to cold and probably accentuated his debility by taking little food. Marcus often complained that many physical feats were now beyond him, and there are "constant laments about pains in his stomach and chest, about blood-spitting, vertigo, sudden spasms of acute pain and other chronic ailments." Many possible causes have been suggested: pulmonary tuberculosis, a gastric ulster or some form of blood disease. Another view is that he was "a hypochondriac reacting to stress".

Soon after becoming emperor, Marcus Aurelius was forced to take action against the growing Parthian empire. The empire was made up of modern Iran, as well as significant chunks of present-day Armenia, Iraq, Georgia, eastern Turkey, eastern Syria, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, Saudia Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar and the UAE. It was an empire that covered 648,000 square miles. In 161 AD Vologases IV launched a serious and unprovoked attack on Armenia, part of the Roman Empire. The governor of Cappadocia (modern central-eastern Turkey), Marcus Sedatius Severianus, moved into Armenia with a legion to expel the intruder, but was trapped by the Parthian army and he committed suicide.

The Parthians then invaded Syria and the Roman governor was forced to flee. Marcus Aurelius appointed Marcus Statius Priscus to deal with the Parthians. However, in early 162 AD Marcus decided that either he or Lucius Verus would have to go East to command in person. He argued that it was not a good idea for an emperor to be absent from Rome for too long. Not surprisingly, Verus was chosen. Cassius Dio claims that "he was physically robust and younger than Marcus, and better suited to military activity".

The Roman Army was going through a crisis at this time. During the reign of Augustus an estimated 68% of the army was of Italian origin, but this reduced to 48% by the year 50 AD and 22% by the year 100 AD. By the time Marcus Aurelius came to the throne, only 2% of the legionaries were Italians. The emperor was told that they needed 7,500 new recruits a year were needed for the legions. This would have equalled 17% of all twenty-year-old males in Italy. It was obvious that Italy would be depopulated and therefore it had been decided to switch to foreign recruitment.

Lucius Verus spent very little time at the front and it was Avidius Cassius who led the Roman Army down the Euphrates, and defeated the Parthians at Dura-Europos. Before the end of the year, Cassius and his legion marched to the south, crossed Mesopotamia at its narrowest point, and attacked and sacked the twin Parthian cities of the Tigris river: Seleucia, which was on the right bank; and Ctesiphon, which was on the left bank and was the Parthian capital. Cassius sent details of his campaign to Rome, for which he was rewarded with elevation to the Senate. By June 166 the war with the Parthians was over.

As an administrator Marcus Aurelius was in general a great believer in the role of the state in the economy. His reign produced a deluge of legislation on the water supply, the architecture of public baths and burial places. As with all emperor, he began his period in power with extensive new road-building and the erection of milestones to show that there was a new ruler in Rome. . He was keen on maintaining streets and highways in a good state and because of traffic congestion, forbade driving or riding in carriages within Rome's city limits.

Marcus Aurelius did not believe in the efficient working of "free markets". He removed the price of grain from the domain of market forces and carefully oversaw its import, concluding that the price of bread was the pre-requisite for a peaceful Rome. Marcus also increased the number of tax collectors, tightened up the collection of inheritance tax, overhauled the customs and excise system and began to investigate more closely local government finance, a major source of corruption. "He insisted that the state have a say in all corners of economic and financial life, whether in regulating trade, managing the relations between business partners or in questions of mortgages and contracts. If, to modern ears, this sounds too interventionist, it must be conceded that in the early years of his reign Marcus enjoyed almost unparalleled popularity."

Under the rule of Hadrian attempts had been made to be more tolerant to Christians. Hadrian stated that merely being a Christian was not enough for action against them to be taken, they must also have committed some illegal act. In addition, "slanderous attacks" against Christians were not to be tolerated, meaning that anyone who brought an action against Christians but failed would face punishment themselves as they could be charged with malicious prosecution.

Antoninus Pius also considered the Jews rather than the Christians as a major problem that had to be dealt with. During his reign he had to deal with two massive Jewish revolts. By contrast, there had never been a Christian rising, nor even so much as a Christian riot. The Jews hated the Christians as renegades who had appropriated the scripture and traditions of Judaism. As a result the Jews often tried to distract Roman attention by foregrounding the Christian threat and investigating persecutions against them.

It is estimated that by 150 AD there were between 50,000 and 100,000 Christians compared to about four or five million Jews in the Roman Empire. Justin Martyr decided that Christianity needed to go on the offensive. In around 155 AD he produced The First Apology of Justin Martyr, Addressed to the Emperor Antoninus Pius. Justin argues that it was the study of Greek philosophy that led him to Christianity. He attempted to explain Christian practices and rituals. He condemned the idea of Christians being persecuted for their beliefs and urged Antoninus Pius to only punish evil actions, writing, "For from a name neither approval nor punishment could fairly come, unless something excellent or evil in action can be shown about it."

Justin also reasserted the idea that Christianity was superior to other religions. The morals of the Christians were of a higher standard than those of the average pagan. Christians believed that virtue would be rewarded in heaven and sin punished in hell. Their sexual ethics had a strictness that was rare in antiquity. Justin believed that they alone would go to heaven, and that the most awful punishments would, in the next world, fall upon the non-Christian.

Justin argued that Socrates was a Christian and like Jesus died the death of a martyr. He also stated that Christians had to be prepared to die for their beliefs. "Justin cited the Sermon on the Mount, the Christian belief that human life is sacred, their famous concern for and love of children, their pacifism, their turn-the-other-cheek compassion, philanthropy and lack of hatred even when persecuted to emphasize the role of the Law of Love as the apogee of morality, entailing truth, purity, generosity, humility, courage, patience, universal love and absence of racial prejudice."

In about 156 AD Justin published The Second Apology of Justin Martyr. Justin now emphasized the importance of martyrdom. "Since we do not place our hopes on the present order, we are not troubled by being put to death, since we will have to die somehow in any case". He also insisted that Christians are not willing to compromise their pacifist beliefs: "The devil is the author of all war... We, who used to kill one another, do not make war on our enemies. We refuse to tell lies or deceive our inquisitors; we prefer to die acknowledging Christ."

Celsus was born in about 120 AD. Very little is known about his personal history except that he lived during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. He was also a follower of early Greek philosophers including Socrates and Plato. In about 160 he published On the True Doctrine: A Discourse Against the Christians. This was an attack on the ideas of Justin Martyr.

It has been argued by Henry Chadwick that in this book, Celsus attempted to justify the traditional polytheistic Roman state religion. He was also the first to recognize the strength of young Christianity: "that this un-political, quietistic and pacifist community had the power to change the social and political order of the Roman empire."

Celsus states that tradition is sovereign, that old-time religions are always superior and that Christianity poses a threat to it. He went on to say that Christianity is a break with the religious traditions of the human race. "Celsus makes it clear he is 'relativistic' in the sense that he recognises that all cannot worship the Olympians, that each nation and culture has its own peculiar ancient laws; all this is fine as long as we are still in the area of the traditional, which means polytheism (the belief in or worship of more than one god)." This argument suggests that Celsus was "a conservative intellectual" who "supports traditional values and defends accepted beliefs".

Celsus points out that Jesus was a Jew: "The Jews, like other separate nationalities, have established laws according to their national genius, and preserve a form of worship which has at least the merit of being ancestral and national, - for each nation has its own institutions, whatever they may chance to be. This seems an expedient arrangement, not only because different minds think differently, and because it is our duty to preserve what has been established in the interests of the state, but also because in all probability the parts of the earth were originally allotted to different overseers, and are now administered accordingly. To do what is pleasing to these overseers is to do what is right: to abolish the institutions that have existed in each place from the first is impiety."

Celsus points out that the Jewish and Christian religious worship only one God (monotheism): "The wisest of nations, cities, and men in every age have held by certain general principles of thought and action: to this ancient tradition the Egyptians, Assyrians, Persians and Indians, Samothracians and Druids, alike adhere; but the Jews and Moses have no part nor lot in it. I pass by those who explain away the Mosaic records by plausible allegorizing. The Mosaic account in regard to the age of the world is false: the flood being in the time of Deucalion was comparatively recent. Neither the teaching nor the institutions of Moses have any claim to originality. He appropriated doctrines which he had heard from men and nations of repute for wisdom. He borrowed the rite of circumcision from the Egyptians. He deluded goatherds and shepherds into the belief that there was one God - whom they called the Highest, or Adonai, or the Heavenly, or Sabaoth, or whatever names they please to give to this world - and there their knowledge ceased. It is of no import whether the God over all be called by the name that is usual among the Greeks, or that which obtains among the Indians or Egyptians."

Celsus admits that Christianity and Judaism were different as they rejected core Jewish customs and laws on circumcision, diet, festivals and keeping the Sabbath. "They cannot have it both ways: either they are a new sect with no relation to Judaism, or they are a cousin of the Jewish faith, in which case they are not entitled to take a pick-and-mix approach to its doctrines. Even some Christians acknowledged that this was a telling point. Judaism was a nationalistic sect, with no claims to universifiability, but Christianity claimed to be a world religion; it was thus both implicitly and explicitly a threat to the Roman empire and to social stability in general: implicitly because of its dogmas, and explicitly because it proselytised. Judaism was compatible with paganism since both practised sacrifice; Christianity emphatically was not."

Celsus attacked the personality of the Christians themselves, condemning them as being uneducated and therefore popular with slaves and the lower classes. "Christianity is for hysterical women, children and idiots." He appealed to a deep Roman snobbery by asking how the thoughts of cobblers and weavers could be put in the same class as the ideas of learned philosophers. He also quoted the words of Epictetus who said that Christians could face death fearlessly because they emphasized the irrational over reason and were childishly ignorant.

"First, however, I must deal with the matter of Jesus, the so-called savior, who not long ago taught new doctrines and was thought to be a son of God. This savior, I shall attempt to show, deceived many and caused them to accept a form of belief harmful to the well-being of mankind. Taking its root in the lower classes, the religion continues to spread among the vulgar: nay, one can even say it spreads because of its vulgarity and the illiteracy of its adherents. And while there are a few moderate, reasonable, and intelligent people who interpret its beliefs allegorically, yet it thrives in its purer form among the ignorant."

Celsus accused Christians of setting up a "church" that diverted allegiances that should properly be the state's, and in worshipping a man (Jesus) instead of a god, thus building up a mere man at the expense of the gods. Roman citizens could not serve two masters and a "house divided against itself must fall". He went onto argue that it was absurd to worship both God and his servant. Not only were Christians building up a man (Jesus) at the expense of God, but since he was dead, they were committing the ultimate blasphemy of worshipping a corpse.

Celsus disagreed that God punished humans by causing earthquakes and floods: "Evils are not caused by God; rather, that they are a part of the nature of matter and of mankind; that the period of mortal life is the same from beginning to end, and that because things happen in cycles, what is happening now - evils that is - happened before and will happen again... Why ought the others, because of these acts, to be accounted wicked rather than this man, seeing they have him as their witness against himself? For he has himself acknowledged that these are not the works of a divine nature, but the inventions of certain deceivers, and of thoroughly wicked men."

Celsus does not deny that Jesus performed miracles, but not because he was the son of God. He claims that Jesus was a master magician and illusionist, trained in Egypt. Celsus suggests that the Virgin Birth is nonsense; what actually happened was that Mary was a poor spinner who committed adultery with a soldier called Panthera and was then kicked out by her carpenter husband. When she gave birth to her illegitimate son, he went to Egypt and learned magic and prestidigitation. Other people can do similar tricks, "so what exactly entitles Jesus thereafter is a mishmash of different traditions."

In On the True Doctrine: A Discourse Against the Christians Celsus attacks the Christian doctrines of creation, original sin, redemption, incarnation and resurrection. He decries the idea that crucifixion (the type of death-penalty reserved by the Romans for the lowest class) could be divine. "So that if he (Jesus) had happened to be thrown off a cliff, or pushed into a pit, or suffocated by strangling, or if he had been a cobbler or stonemason or blacksmith, there would have been a cliff of life above the heavens, or a pit of resurrection, or a rope of immortality, or a blessed stone, or an iron of love, or a holy hide of leather. Would not an old women who sings a song to lull a little child have been ashamed to whisper such tales as these."

Celsus admitted that there were a lot of myths in Roman culture. However, Romans knew they were myths but Christians had the audacity to expect us to believe that their myths are true. "Why is it a narrative at the higher level of reliability than the stories about the Greeks and the Trojans, Oedipus and Iocasta and the other myths? Celsus claims that chief witness was a hysterical female (Mary Magdalene) who was "half crazy from fear and grief, and possibly one other of the same band of charlatans who dreamed it all up or saw what they wanted to see - or more likely simply wanted to astonish their friends in the tavern with a good tale."

Celsus was especially critical of the doctrine of Incarnation. If an omnipotent God wanted to achieve the moral reformation of humanity, why did he not do so by a simple exercise of willpower? As for redemption, what about all the innumerable people who lived before he was incarnated? Don't they count, or did God simply not care before the Christian era? "Whichever answer we give, it will not satisfy Christian doctrine. Maybe God is not omnipotent, omniscient or benevolent, or maybe he possesses at most two out of the three attributes? Whatever the case, he emerges as the kind of arbitrary and capricious deity that only morans could believe in."

One of Marcus Aurelius' first decisions was enforce the requirement to sacrifice to the Roman gods. The first recorded example of this concerns three Christians, Carpus, Papylus, and Agathonice, who were traveling through Pergamum. The Roman governor Pergamos ordered them to sacrifice to their gods in the name of the emperor. Carpus was the first to refuse and he was hung up on a meathook and "scraped". Despite seeing his friend treated this way, Papylus, refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods. So did Agathonice, a woman, and the three of them were burned alive.

In 165 AD Justin was ordered to appear before the prefect, Junius Rusticus, where he was cross-examined by the cynic philosopher, Crescens. He was asked what doctrines do you practise. He replied: "I have tried to learn all doctrines, but I have committed myself to the true doctrines of the Christians, even if they do not please those with false beliefs." Rusticus warned that "those unwilling to sacrifice to the gods are to be scourged and then executed in accordance with the laws." Justin refused and Rusticus asked him that "if you are scourged and beheaded, do you believe that you will ascend to heaven?" Justin replied: "I hope for it if I am steadfast in my witness. But I know that for those who live the good life there awaits the divine gift even to the consummation."

Crescens asked Justin if Christians welcomed death and martyrdom, they should kill themselves. Justin replied that the two things were not the same, and that mass suicide by Christians would mean that the word of God could not be spread. Crescens commented that if God was on the side of the Christians, he would rescue them. Justin replied that since God permitted free will, it allowed evil men like Crescens to rise up. The purpose of martyrdom was the belief that this public act of witness, was intended to give heart to the less intrepid Christian brethren and to make a demonstration of faith before unbelievers. Justin and five of his followers were then scourged with whips and beheaded."

According to Eusebius, the next major victim was Polycarp , the Christian bishop of Smyrna (in modern-day Turkey). At the age of eighty-six the local Jewish community denounced him as refusing to sacrifice to the Roman gods. He appeared before the provincial governor, who told him that unless he changed his mind he would be punished by being fed to wild beasts. However, when he still refused and he was burnt at the stake. According to Christian legend Polycarp was so pure that his body would not burn."

In 177 AD people living in Lyon began to demonstrate against the small Christian community (most of them were Greek immigrants). The main charges against them were cannibalism and incest. Large numbers were rounded up by vigilante groups and then herded into the town forum. When a senior figure in the city, Vettius Egapathus, attempted to intervene on behalf of the accused, the mob called for him to be executed. The Christians were tortured and beaten and their leader, Pothinus, a 90-year old bishop, died from his injuries. The rest were taken into the local stadium where they were torn apart by wild animals. After six days their bodies were burned and the ashes throne into the Rhône. "The elated persecutors were heard to gloat that it would be interesting to see how the Christian god would be able to resurrect piles of ashes into risen bodies."

Another persecution of Marcus Aurelius's reign took place in North Africa. In the summer of 180 AD twelve Christians (seven men and five women) living in Scillium, a town in Numidia, were brought before the proconsul Vigellius Saturninus and accused of not sacrificing to the Roman gods. Speratus, their leader, made a statement to the court: "We too are religious, and our religion is simple, and we swear by the Genius of our lord the emperor, and we pray for his welfare, as you also ought to do... I do not recognise the empire of this world, but rather I serve that God who no man sees or can see with these eyes. I have committed no theft; but if I buy anything, I pay the tax, because I recognise my lord, the king of kings and the emperor of all peoples... it is evil to advocate murder or the bearing of false witness." The twelve Christians were found guilty and beheaded.

The persecutions under Marcus Aurelius hit the Christian communities very hard and has been dubbed "the years of crisis". The pogroms and martyrdoms of his reign convinced many Christians that the end of the world was at hand, while others changed their beliefs. Historians have claimed that during this period there was a growth of Gnosticism because Gnostics were not persecuted because they agreed to take part in pagan religious ceremonies.

Eusebius claims that Marcus Aurelius instigated the persecutions of Christians at the beginning of his reign. Other historians like Herbert Brook Workman and Elizabeth Livingstone have agreed with Eusebius. It has been pointed out that previous emperors, Trajan, Hadrian and Antoninus Pius, had issued orders forbidding victimisation of Christians. The prosecutor of Justin Martyr., the prefect Junius Rusticus, was a close friend of Marcus. The eminent historian, Albino Garzetti, has argued that these persecutions could not have taken place without his knowledge.

Frank McLynn argues that the primary sources that have survived suggest that this hostility was caused by Christian morality. Christians had a manifestly superior attitude to sexuality: they were not promiscuous, did not believe in sex outside marriage - and inside it only for the purpose of procreation - abortion or even remarriage, which in their view was still adultery... They raised large sums of money by voluntary contributions, which went on supporting the needy, widows, orphans, the aged, shipwrecked travellers... Christians shared everything except their wives.

Eusebius claims that Christians were much better treated under Marcus Aurelius's successor, Commodus: "During his reign our affairs took an easier turn and, by the grace of God, the churches throughout the world were lapped in peace... already large numbers even of people at Rome, of the wealthy and the wellborn, were drawing towards salvation with their household and kindred."

There is indeed no documentary evidence that Marcus Aurelius ordered the persecution of Christians. However, no one doubts that Adolf Hitler ordered the Final Solution and the Holocaust, but on one has ever been able to find a document in his hand so ordering it. Rulers who commit atrocities, even those they consider justifiable for reasons of state, rarely leave written evidence of their deeds for posterity to find."

The writings of Marcus Aurelius have convinced some people that they were in support of Christianity. However, Stoicism was an elitist creed that was only available to those who could afford to live a life of reason. Christianity offered salvation to all. Marcus feared that Christians were winning the ideological battle against their pagan rivals and that it might pose a serious threat to both Stoicism and the official Roman religion.

The final piece of evidence for Marcus's attitude to the Christians comes from his own The Meditations, where he contrasts the heroic doctrine of suicide by the Stoics with Christian martyrdom: "How resolute is the soul! Ready to be released from the body at any moment, whether to be extinguished, to be scattered or persist. But this readiness has to be the result of its own decision, not a mindless reflex, like the Christians; it should happen after reflection, with dignity and in such a way as to convince others, without any histrionics."

In 165 AD the Roman Empire experienced the first outbreak of the Antonine Plague. It is believed that pandemic brought back to the Roman Empire by troops returning from the Parthian War. Some people have claimed that it was an outbreak measles but although it was responsible for a large number of deaths in the ancient world, this outbreak is generally considered to be smallpox. It then spread north as far as the Rhine and Britain. Over the next fifteen years an estimated five million died from the disease.

The minute observations of Galen has helped historians identify the pestilence as smallpox. After the incubation period of about twelve days between contraction of the disease and first symptoms, a flu-like syndrome develops - fever, high temperature, muscle pain, headache, backache, nausea and vomiting. After about two weeks the first visible lesions (small reddish spots) appear. These lesions become pustules, which feel like small beads in the skin. After seven to ten days they reach their maximum size and rupture. The bleeding occurring under the skin makes it appear black. Death is caused by massive haemorrhage in all the vital organs. The mortality rate is between 90% and 100%.

Epidemics and pandemics always produce outbreaks of scapegoating. To many the plague seemed the final refutation of Stoicism, Others blamed the Christians. As Frank McLynn has pointed out: "Undoubtedly one of the deep causes of the persecution of the Christians in Marcus's reign, and certainly not discouraged by the emperor, was the perception that they had caused the plague, either by the black magic of their Christian god or by angering the Olympians with their blasphemy."

The Marcomanni, based in Bohemia, emerged as the principal power in Germany. They joined forces with other German tribes, and in July 167 AD they launched a surprise attack on the Roman Empire and in the first couple of weeks over 20,000 Roman citizens were killed and large numbers were taken into slavery. They arrived outside Aquileia, a city of 100,000 inhabitants. It had grown rich from the amber trade and the discovery of gold fields in the area.

The German tribes eventually retreated but the damage done to Roman prestige was immense. Other German invasions took place and Marcus Aurelius realised he faced a war with a massive German federation along a front extending from the source of the Danube in the Black Forest to its estuary in the Black Sea. The Romans had always respected the fighting abilities of the German tribes. Tacitus pointed out: "The fame and the strength of the Marcomanni are outstanding... nor are the Naristae and Quadi inferior to them; these tribes are, so to speak, the brow of Germany, so far as Germany is wreathed by the Danube."

Marcus Aurelius called on the help of the Roman gods. "Evincing at once his deeply superstitious nature and his religious eclecticism, he carried out further ceremonies, not just those directed to the Olympians, but aimed at enlisting the possible help of other gods: Isis, Magna Mater, Mithras, and so on (but not, of course, Jesus Christ). He carried out all the non-Roman rites, summoned priests of every stripe and denomination, and purified the city by every known technique."

Marcus Aurelius also began raising money to pay for new troops. Leading by example, Marcus conducted a two-month sale of imperial effects and possessions, putting under the hammer not just sumptuous furniture from the imperial apartments, gold goblets, silver flagons, crystals and chandeliers. Marcus also persuaded his wife, Faustina, to sell some of gold-embroided robes and her jewels. This was more a propaganda move than a serious fund-raising effort, but it had the desired impact on the citizens on Rome.

A massive recruiting campaign took place. This included the assembling of special units, for which he recruited from slaves and gladiators. He also paid money to members of bandit groups to abandon their life of crime in order to serve in the Roman Army. Altogether, the equivalent of about six modern divisions were recruited by these unusual methods. He also withdrew troops from Britain to join the army being prepared to take on the German tribes. By the spring of 168 AD Marcus was ready to take his army to make a morale-boosting visit to Aquileia.

Aged 47 and already an old man by Roman standards, Marcus for the first time in his life traveled beyond southern Italy. He was unwilling to leave his co-emperor Lucius Verus behind in Rome and insisted he accompany him to Aquileia. Those living in the city were delighted by the visit and Marcus announced instructions for the building of more forts along the frontier. While in the city news was received of an interim truce signed with the Germans on the Danube.

In January 169 Marcus and Lucius decided to return to Rome. Soon after leaving Aquileia Lucius was taken ill and died following an apoplectic stroke. However, there were numerous conspiracy theories concerning his death. This included the claim that Marcus had Verus poisoned: "That hardy perennial of ancient conspiracy theories - the knife used to cut up meat that was poisoned on one side only - duly made its appearance, though some said Marcus had employed a physician named Posiddipus to overbleed his fellow emperor, since bloodletting was then considered a panacea. A more outré theory was that Marcus's wife Faustina had been Verus' lover - technically an act of incest, since her daughter Lucilla was his wife; somehow Faustina blurted this out to her daughter Lucilla was his wife; somehow Faustina blurted this out to her daughter, whereat one or other of the two women (or possibly the two in collusion) poisoned Verus with oysters to prevent this scandal from ever coming out."

Marcus Aurelius began writing The Meditations in about 165 AD. The book is a series of personal notes taken on a daily basis, which was a common practice in the ancient world, particularly as an aid to self-improvement. It is clear that he has been deeply influenced by the ideas of Socrates, Heraclitus, Diogenes and Epictetus. It is generally agreed that Marcus used his writings as a "kind of meditative technique, that they were intended for his eyes only, and that he had to real ambitions as an author."

He was very interested in the way people should live and they should only be concerned with the present. This point is made several times: "Limit yourself to the present." "The present is the same for everyone; its loss is the same for everyone". "Forget everything else. Keep hold of this alone and remember it. Each of us lives only now, this brief instant." "If you've seen the present, then you've seen everything - as it's ever been since the beginning, as it will be forever." "For me the present is constantly the matter on which rational and social virtue exercises itself." "Past and future have no power over you. Only the present - and that can be minimised."

Marcus Aurelius wanted to live in a harmonious society without conflict: "Begin the morning by saying to thyself, I shall meet with the busy-body, the ungrateful, arrogant, deceitful, envious, unsocial. All these things happen to them by reason of their ignorance of what is good and evil. But I who have seen the nature of the good that it is beautiful, and of the bad that it is ugly, and the nature of him who does wrong, that it is akin to me, not only of the same blood or seed, but that it participates in the same intelligence and the same portion of the divinity, I can neither be injured by any of them, for no one can fix on me what is ugly, nor can I be angry with my kinsman, nor hate him, For we are made for co-operation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be vexed and to turn away."

Marcus Aurelius, like most educated Romans, did not really believe in the Olympian gods (or, indeed, any gods). "It was almost a badge of honour for the senatorial class to be sceptics, as though this was a mark of their status, and the belief in the gods something for the mob at the arena and the Circus." Cicero was a convinced atheist but thought religion and belief in the Olympians played a vital part in promoting social stability. However, Marcus did not believe in an afterlife: "He who fears death either fears to lose all sensation or fears new sensations. In reality, you will either feel nothing at all, and therefore nothing evil, or else, if you can feel any sensations, you will be a new creature, and so will not have ceased to have life."

Alan Stedall, the author of Marcus Aurelius (2005) became a Christian after reading The Meditations:"Marcus Aurelius... tried his best to live by essentially pre-Christian Stoic principles and, it seems, had largely succeeded... The Stoic philosophy on which many of Marcus's beliefs were based was founded upon the intellectual lineage of great Greek philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Cleanthes. However, Marcus's personal belief-set was not purely Stoic: it was heavily biased by, and overlaid with, strong humanistic beliefs. His was not a cold-hearted and detached Stoicism; it was, above all, kindly, cheerful, understanding and forgiving of his fellow man."

Marcus Aurelius gave advice to future emperors: "Take heed not to be transformed into a Caesar, not to be dipped in the purple dye, for it does happen. Keep yourself therefore, simple, good, pure, grave, unaffected, the friend of justice, religious, kind, affectionate, strong for your proper work. Wrestle to be the man philosophy wished to make you. Reverence the gods, save men. Life is brief; there is but one harvest of earthly existence, a holy disposition and neighbourly acts."

Marcus Aurelius wrote a great deal about morality: "It is not fit that I should give myself pain, for I have never intentionally given pain even to another." "Men exist for the sake of one another. Teach them then or bear with them." "In the constitution of that rational animal I see no virtue which is opposed to justice, but I see a virtue which is opposed to love of pleasure, and that is temperance." "The happiness and unhappiness of the rational, social animal depends not on what he feels but on what he does; just as his virtue and vice consist not in feeling but in doing."

Marcus Aurelius died of natural causes at the age of 58 on 17th March 180. Marcus was succeeded by his son Commodus, whom he had named Caesar in 166 and with whom he had jointly ruled since 177. Cassius Dio said of the dead emperor. "Marcus did not meet with the good fortune that he deserved, for he was not strong in body and was involved in a multitude of troubles throughout practically his entire reign. But for my part, I admire him all the more for this very reason, that amid unusual and extraordinary difficulties he both survived himself and preserved the empire. Just one thing prevented him from being completely happy, namely, that after rearing and educating his son in the best possible way he was vastly disappointed in him."

On this day in 1715 Gilbert Burnet died. Burnet was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 18th September, 1643. He studied in Aberdeen before joining the Church of Scotland.

In 1669 Burnet became Professor of Divinity at Glasgow University. However, he resigned five years later after a disagreement with his patron, the Duke of Lauderdale. He now moved to London where he became an active supporter of the Whigs.

In 1683 Bumet was accused of plotting against James II and he was forced to flee to Holland. When William of Orange became king he appointed Bumet as his royal chaplain. Later Bumet became Bishop of Salisbury.

Bumet wrote several books including History of the Reformation (1679), Exposition of the Thirty-Nine Articles (1699) and History of My Own Time (1724).

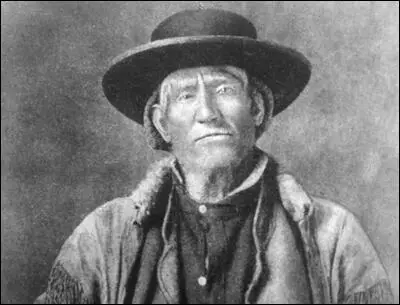

On this day in 1804 Jim Bridger was born at Richmond, Virginia. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed to a blacksmith in St. Louis.

On 13th February, 1822, William Ashley placed an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette and Public Adviser where he called for 100 enterprising men to "ascend the river Missouri" to take part in the fur collecting business. Those who agreed to join the party included Bridger, Tom Fitzpatrick, William Sublette, David Jackson, Hugh Glass, Jim Beckwourth and Jedediah Smith.

In August 1823, Bridger was a member of a party led by Andrew Henry. One of the men, Hugh Glass, was badly mauled by a bear. Henry, left Bridger and John Fitzgerald, behind to look after him. They became convinced he could not live and after taking his gun and equipment, abandoned him. When Bridger and Fitzgerald caught up with Henry they reported that Glass had died from his injuries.

However, Glass did regain consciousness and by eating wild berries and roots, he managed to crawl along the side of the Grand River. With the help of Native Americans Glass eventually reached Fort Kiowa. Glass now decided to track down and kill Bridger and Fitzgerald. Glass eventually found Bridger but decided to forgive him because of his age. He also discovered that Fitzgerald had joined the army and was no longer living in the region.

In 1824 Bridger discovered the Great Salt Lake. He also went trapping with William Sublette, David Jackson and Jedediah Smith in the Wasatch Mountains in Utah. Later he helped establish the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Bridger developed a reputation as a courageous mountain man and was willing to work as a trapper in dangerous Blackfeet country. In 1832 he was hit in the back with an arrowhead. He recovered and in 1835 worked with Kit Carson and Joe Meek. After the trip was completed Bridger managed to get Dr. Marcus Whitman, a medical missionary, to cut out the arrowhead from his back.

In 1843 Bridger established Fort Bridger, a trading post on Black's Fork of Green River in Wyoming. Over the next few years the post became established as a resting place and supply station for wagon trains on the Oregon Trail. Bridger also employed his blacksmith's skills in the fort. Later it also became a pony express station.

After his first wife died, Bridger married a Ute woman. She died in childbirth and in 1850 he married a Shoshone. The couple had two children.

In 1853 Bridger upset local Mormons by selling weapons to Native Americans. An attempt was made to arrest him and Bridger fled to the mountains. Later he moved to Fort Laramie. He continued to work as a guide and accompanied General Albert S. Johnston during his military campaign (1857-58). In 1868 he settled in Westport, Missouri.

Jim Bridger, who he lost his sight in the 1870s, died on 17th July, 1881.

On this day in 1808 John Covode, was born in West Fairfield, Pennsylvania. Involved in the coal industry, Covode was active in the Whig Party and was elected to the 34th Congress in 1855.

An opponent of slavery Covode joined the Republican Party and was re-elected to the 35th Congress in 1857. Over the next few years he was associated with the group known as the Radical Republicans. Covode strongly supported the Freeman's Bureau, the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. After the American Civil War Covode clashed with President Andrew Johnson and voted for his impeachment in 1868.

John Covode, who was chairman of the Committee of Public Expenditures (1857-59) and the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds (1867-69), remained in Congress until his death at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on 11th January, 1871.

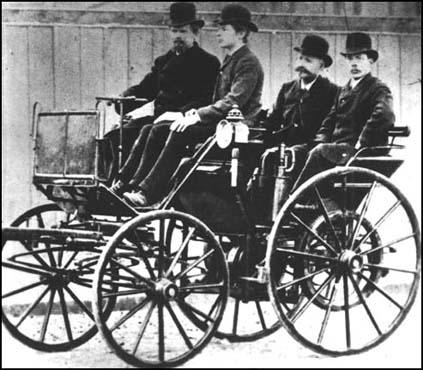

On this day in 1834 Gottlieb Daimler was born in Schorndorf in Germany. After training as a gunsmith he became an engineer. He worked in Britain, France and Belgium before being appointed technical director to the gas-engine company which Nikolaus Otto founded at Deutz.

Daimler now worked with Otto and a young engineer, Wilhelm Maybach, in an attempt to develop the internal combustion engine for propelling road vehicles. After a dispute with Nikolaus Otto in 1882, Daimler and Maybach set up their own company.

Daimler and Maybach concentrated on producing the first light-weight, high-speed engine to run on gasoline. They eventually came up with an engine with a surface carburettor, that vaporized the petrol and mixed it with air. Whereas the engine that they produced with Nikolaus Otto achieved 130 revolutions per minute, Daimler and Maybach's engine reached 900 revolutions per minute.

In 1889 Daimler and Maybach placed their engine into a horse carriage and drove the car at speeds of 11 miles per hour. They had therefore produced the first four-wheeled automobile. After the men had had devised a four-speed gearbox and a belt-drive mechanism to turn the wheels they decided to sell these cars.

The Daimler Motor Company was launched in 1890. The company soon developed a reputation for reliability. In the first road race held between Paris and Rouen in 1894. Only 15 of the 102 cars completed the course. All 15 cars were powered by Daimler engines.

This impressed Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, who decided to use Daimler engines in the airships he was building. They were also used in the armoured cars that were being developed during this period. Gottlieb Daimler died in 1900 but Wilhelm Maybach continued to develop the Mercedes car and the Zeppelin Airship.

On this day in 1873, Margaret Bondfield, the daughter of William Bondfield and Anne Taylor, was born in Chard, Somerset. Margaret was Anne's eleventh child and her husband was at that time was sixty-one years old. William Bondfield had worked in the textile industry since he was a young boy and was well known in the area for his radical political beliefs. Philip Williamson has argued: "Her parents gave her a nonconformist faith and ethic, a strong sense of the dignity of work, and a belief in an active female role, while contact with philanthropists and preachers encouraged her to read widely about social, ethical, and spiritual issues."

At the age of fourteen Margaret left home to serve an apprenticeship in a large draper's shop in Hove. She later recalled: "When I first went to Brighton for a holiday in 1887 I had the chance of a job as apprentice to Mrs. White of Church Road, Hove, a friend of my sister Annie. I eagerly grasped this opportunity of earning my living. I did not see my home again for five years. Mrs. White successfully ran one of those old-fashioned businesses where the relations between the customer and assistant were of the most courteous and friendly, and the assistants, of whom I was the youngest, were treated like members of the family."

Margaret Bondfield became friendly with one of her customers, Louisa Martindale, a strong advocate of women's rights. Margaret was a regular visitor to the Martindale home where she met other radicals living in Brighton. Louisa Martindale lent Margaret books and was an important influence on her political development.

In 1894 Margaret went to live with her brother Frank in London. Margaret found work in a shop and after a short period was elected to the Shop Assistants Union District Council. In 1896 Clementina Black of the Women's Industrial Council asked Bondfield to carry out an investigation into the pay and conditions of shop workers. Bondfield's report was published in 1898, the same year she was appointed assistant secretary of the Shop Assistants' Union.

As a result of her work for the Women's Industrial Council, Bondfield became known as Britain's leading expert on shop workers and gave evidence to the Select Committee on Shops (1902) and the Select Committee on the Truck System (1907). During this period she met Mary Macarthur: "I saw a thin white face and glowing eyes, and then I was enveloped by her ardent, young hero-worshipping personality. She was gloriously young and self-confident It was a dazzling experience for a humdrum official to find herself treated with the reverence due to an oracle by one whose brilliant gifts and vital energy were even then manifest." As a Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) executive member, she recommended Macarthur as organizer and in 1906 they established the first women's general union, the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW).

Margaret Bondfield made the decision to concentrate on her career. In her autobiography, A Life's Work (1948): "I concentrated on my job. This concentration was undisturbed by love affairs. I had seen too much - too early - to have the least desire to join in the pitiful scramble of my workmates. The very surroundings of shop life accentuated the desire of most shop girls to get married. Long hours of work and the living-in system deprived them of the normal companionship of men in their leisure hours, and the wonder is that so many of the women continued to be good and kind, and self-respecting, without the incentive of a great cause, or of any interest outside their job... I had no vocation for wifehood or motherhood, but an urge to serve the Union".

Bondfield was chairperson of the Adult Suffrage Society. In 1906 she made a speech where she said: "I work for Adult Suffrage because I believe it is the quickest way to establish a real sex-equality... I have always said in my speeches and in conversation that these women who believe in the same terms as men Bill have a perfect right to go on working for that Bill, and I say good luck to them and may they get it! But don't let them come and tell me that they are working for my class."

Unlike some members of the NUWSS and the WSPU, Bondfield was totally opposed to the idea that initially only certain categories of women should be given the vote. Bondfield believed that a limited franchise would disadvantage the working class and feared that it might act as a barrier against the granting of adult suffrage. This made Bondfield unpopular with middle class suffragettes who saw limited suffrage as an important step in the struggle to win the vote.

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) described a debate she had with Isabella Ford over the issue of women's suffrage: The young Margaret Bondfield tore to shreds the argument that a limited women's franchise was the way forward. Industrial organisation would improve women's lot much more efficiently than votes, she said. If women were to have the vote at all, they should have it as part of a much more radical move towards universal suffrage for both men and women." Sylvia Pankhurst did not agree with this assessment: "Miss Bondfield appeared in pink, dark and dark-eyed with a deep, throaty voice which many found beautiful. She was very charming and vivacious and eager to score all the points that her youth and prettiness would win for her against the plain middle-aged woman with red face and turban hat... Miss Bondfield deprecated votes for women as the hobby of disappointed old maids whom no-one had wanted to marry."

In 1908 Margaret Bondfield resigned from the Shop Assistants' Union and became secretary of the Women's Labour League. Bondfield was also active in the Women's Co-operative Guild which was campaigning for minimum wage legislation, an improvement in child welfare and action to lower the infant mortality rate. Her biographer, Mary Agnes Hamilton, commented that "any deficiences... are offset by her personal charm."

In 1910 the Liberal Government asked Bondfield to serve as a member of its Advisory Committee on the Health Insurance Bill. Bondfield's efforts were rewarded when she persuaded the government to include maternity benefits. Bondfield also influenced their decision to make the benefit the property of the mother.

Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett announced that the NUWSS was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Bondfield disagreed with the position that the NUWSS and WSPU took during the First World War. She joined forces with the Women's Freedom League to establish the Women's Peace Crusade, an organization that called for a negotiated peace. Other members included Charlotte Despard, Selina Cooper, Margaret Bondfield, Ethel Snowden, Katherine Glasier, Helen Crawfurd, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Mary Barbour.

In October 1916 Bondfield joined with George Lansbury and Mary Macarthur to set-up a new National Council for Adult Suffrage. The main plan was to persuade the government to reconsider its plans for a limited extension of the franchise. At the time, the Manchester Guardian commented: " She is a little woman but her pleasantly toned, deep voice has great carrying power. I have often seen her sway an audience and lift it for the moment to the height of some great idea by the force of her own feeling and deep sincerity."

In 1923 Margaret Bondfield became one of the first women to enter the House of Commons when she was elected as Labour MP for Northampton. When Ramsay McDonald became Prime Minister in 1924 he appointed Bondfield as parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Labour. One political commentator described her as: "Small in stature with dark hair, wide brows, and bright dark eyes, she reminded her hearers of a courageous robin as, in her clear, resonant, musical voice she told them that the unions must get together for political action if they were to achieve their larger aims."

Bondfield welcomed the passing of the 1928 Equal Franchise Act. She commented in the House of Commons: "Since I have been able to vote at all I have never felt the same enthusiasm because the vote was the consequence of possessing property rather than the consequence of being a human being... At last we are established on that equitable footing because we are human beings and part of society as a whole."

When Ramsay McDonald became Prime Minister for a second time in 1929 he appointed Bondfield as his new Minister of Labour. Bondfield therefore became the first woman in history to gain a place in the British Cabinet. In the financial crisis of 1931, Bondfield upset many members of the Labour Party when she supported the government policy of depriving some married women of their unemployment benefit. However, she refused to join McDonald's National Government and lost her seat in the 1931 General Election.

As Fran Abrams has pointed out, this brought an end to her career in the House of Commons: "Her seat lost and her parliamentary career at an end, Margaret suffered a complete breakdown. She was ordered to bed with fibrositis - generalised muscle pain - for which she underwent painful treatment, but it was clear she was in poor emotional as well as physical shape. After a long rest she spent several months touring the US before returning to fight Wallsend again in 1935 without success. She was then adopted as Labour candidate for Reading, but she gave up her candidature when it became clear the election would be long delayed by the Second World War."

Margaret Bondfield died at Verecroft Nursing Home, Sanderstead on 16th June 1953.

On this day in 1877 Edith New, one of five children of Isabella Frampton New, a music teacher, and Frederick James New, a railway clerk was born in Swindon. Her father was killed by a train in 1878.

In 1891, aged 14, she began working as a teacher. New was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1906 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union. Established by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, it had become frustrated by the lack of success by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

New was one of those who believed that the WSPU should adopt more militant tactics. In January 1908 Edith New and Ada Nield Chew chained themselves to the railings of 10 Downing Street. According to The Daily Express: "Each suffragist wore round her waist a long, steel chain - not unlike a very heavy dog chain. Each took the loosened end of the chain, threw it round the railings, and fixed it to the rest of the chain. This was done so deftly that it was not until the police heard the click of the lock that they understood the clever move by which the suffragists had outwitted them, and prevented for a time their own removal. Votes for women! shouted the two voluntary prisoners simultaneously. Votes for Women!"

On 30th June, 1908, Edith New attended a public meeting in Parliament Square. The authorities decided to send in 5,000 foot police and 50 mounted men to break-up the meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst later reported: "Women spoke from the steps of the Government buildings and offices in Broad Sanctuary, they lifted themselves above the people by the railings round the Abbey Gardens and Palace Yard, or raised their voices standing among the crowds on road or pavement. They were torn by the harrying constables from their foothold and flung into the masses of people... Then roughs appeared, organized gangs, who treated the women with every type of indignity... I was obliged to drop my handbag with keys and purse, to have my hands free to protect myself. The roughs were constantly attempting to drag women down side streets away from the main body of the crowd... Enraged by the violence and indecency in the Square, Mary Leigh and Edith New took a cab into Downing Street, and flung two small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house." It was later revealed that these gangs had been hired by Scotland Yard.

The next day at Westminster police court twenty-seven women were sent to prison for terms varying from one to two months. Edith New and Mary Leigh, were sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In court the women wore white dresses and were relieved to hear the sentence because they feared it would be a much longer sentence. However, the Manchester Guardian protested in a leading article: "Their stringent imprisonment... violates the public conscience." However, Millicent Fawcett, leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), said later that it was this incident that resulted in her condemning the methods being used by the WSPU.

Edith New and Mary Leigh were released from prison on 23rd August. They were welcomed on release by a team of women in white dresses who drew their carriage from Holloway to Clements Inn. They were greeted by a brass band and accorded a ceremonial welcome breakfast attended by the two main leaders of the WSPU, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst.

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”