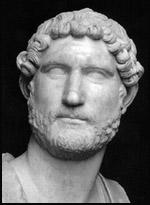

Emperor Hadrian

Publius Aelius Hadrianus (Hadrian) was born in Italica on 24 January, AD 76. Hadrian was a descendent of a Roman soldier who had been stationed in Baetica in the third century BC. Like many Roman soldiers, when he retired, he was given land in the country he had helped to conquer. After marrying a local woman, this former Roman soldier became a successful farmer.

The Hadrianus family stayed in Spain and over the centuries they produced several soldiers who had distinguished military careers. Hadrian's own father was also a high-ranking soldier and was able to afford a good education for his son.

When Hadrian was only ten his father died. It was a Roman tradition that a male guardian should be appointed when a child's father died. A relative named Trajan agreed to become Hadrian's guardian. Trajan was a prominent Roman general and as soon as he was old enough Hadrian accompanied Trajan on his military campaigns.

Trajan was a very successful military commander and when Nerva died in AD 98 Trajan's name was put forward as the next emperor. This was a very controversial suggestion as Trajan came from Baetica, whereas all previous emperors had been born in Italy. However, as Trajan had the support of the Roman Army, the Senate was powerless to stop him from becoming emperor.

As Trajan spent most of his time in office fighting in foreign wars, his wife Pompeia Plotina played an important role in running the empire. Plotina, who had no children of her own, had grown very fond of Hadrian and he was a great help to her while her husband was away.

When Trajan died in AD 117 he left a letter nominating Hadrian as Rome's next emperor. Many senators were against Hadrian holding this position. They claimed that Pompeia Plotina had forged the letter in an attempt to keep herself in power. They also objected to a man with a foreign accent ruling the empire.

Hadrian acted quickly. He immediately ordered the distribution of money to the people of Rome and arranged for all soldiers to be paid an extra bonus. Hadrian also cancelled the debts of all those people who had borrowed money from the treasury. Finally, to gain the support of the Senate, he promised he would never have any of them punished unless they were found guilty of an offence by their own court.

For the first few years of his rule Hadrian relied heavily on the advice of Pompeia Plotina. When Plotina became empress she is reported to have told the Roman people as she entered her palace: "I wish to be the same sort of woman when I leave as I am on entering." Plotina was aware of how the previous emperors had been corrupted by the tremendous power they held and worked hard to prevent this happening to Trajan and Hadrian.

Hadrian took Plotina's advice and made every effort not to cut himself off from ordinary people. For example, when Hadrian took part in military campaigns he ate the same food as his soldiers and marched with them instead of using a horse.

Hadrian also believed it was important to show modesty. Although he was a talented poet and musician, he kept quiet about it. Hadrian was also one of the most creative architects the world has ever seen. However he refused to take credit for his work. He even put other people's names on the buildings he designed, and it is only in recent years that historians have discovered that it was Hadrian who was responsible for the Pantheon, one of the most important buildings in the development of world architecture.

Although Hadrian agreed with slavery, he believed that in the past Romans had been too cruel to slaves. He therefore made several changes to the law on slavery. People who owned slaves no longer had the right to kill them. Nor were they allowed to force their slaves into becoming gladiators or prostitutes. Hadrian also abolished slave labour-camps. Finally, he changed the law that stated that if a man was killed by a slave, all his slaves would be executed.

Hadrian spent most of his period in office travelling all over the empire. He realised that Rome no longer had the men or financial resources to protect such a large area, and therefore took the decision to withdraw from some of the territories in the east.

Once he had decided what the new frontiers should be, Hadrian made arrangements that they should be well guarded. For example, when Hadrian visited Britain in AD 121, he gave orders for a 117 km stone wall to be built across northern Britain. Every four miles along the wall was a fort. As there were also several signal-turrets between each fort, it was possible to pass a message from one end of the wall to the other in a matter of minutes. As a good road had been built along the length of the wall, it did not take the Romans long to direct their troops to areas under attack.

Throughout most of his time as emperor, Hadrian was considered to be a tolerant ruler. However, after the death of Pompeia Plotina, Hadrian began to persecute people who did not agree with him. His main target was the Jews who refused to worship Roman gods.

In AD 132 the Jews in Palestine rebelled against the Romans. Initially the Jewish uprising, led by a man called Simon bar Kokhba, was successful. However, it was not long before Roman reinforcements arrived in Palestine. By AD 134 the Romans were back in control. It has been estimated that over half a million Jews were killed during the war, while many others were sold into slavery.

In his later years Hadrian began to lose the support of the Senate. Although Hadrian had always said that emperors should be obeyed out of love rather than fear, he now changed his tactics. In an attempt to hold on to power, he ordered the execution of several senators.

Aware that he was dying, Hadrian decided to make arrangements for the future of the Roman Empire. By the time he died in AD 138, Hadrian had forced the Senate to agree to the names of the next two emperors, the elderly Antoninus Pius, followed by the much younger Marcus Aurelius. It was a wise decision as both men went on to become successful emperors.

Primary Sources

(1) Cassius Dio, Roman History (c. AD 215)

He (Hadrian) personally viewed and investigated absolutely everything, not merely the usual... such as weapons, engines, trenches, ramparts and palisades, but also the private affairs of everyone, both of the men serving in the ranks and the officers.

(2) Eusebius, History of the Church (c. AD 325)

Hadrian... moved against the Jews... He destroyed thousands of men, women and children, and, under the law of war, enslaved their land... Hadrian then commanded that by a legal decree that the whole nation

should be prevented from entering Jerusalem... It was colonised by foreigners, and the Roman city changed its name.

Questions

1. What was the connection between Hadrian's father dying in AD 86 and Hadrian becoming emperor in AD 117?

2. On a time-line dated from AD 76 to AD 138, mark down the main events of Hadrian's life.

3. It has been claimed that Plotina had a large influence over the decisions made by Trajan and Hadrian when they were emperors. What kind of sources would you need to look at to see if there was any truth in this claim?